Abstract

Despite the proliferation of initiatives to integrate services for people with serious mental illness (SMI), measures of distinct dimensions of integration, such as spatial arrangement and care team expertise, are lacking. Such measures are needed to support organizations’ assessment of progress toward integrated service delivery. We developed measures characterizing integration of behavioral, somatic, and social services to operationalize the integrated care dimensions conceived by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. In a survey fielded to 46 Maryland Medicaid health homes (response rate: 96%) serving adults with SMI during 2015–2016, we found that these measures provided a useful description of variation across dimensions of integration.

Keywords: integrated delivery systems, mental disorders, measure development

Background

Long-standing fragmentation in the financing and delivery of mental health care, substance use treatment, somatic care, and social services stymies efforts to improve the health and wellbeing of individuals with serious mental illness (SMI), one of the most vulnerable populations in the US. This group experiences significant premature mortality (Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal, & Stroup, 2015; Saha, Chant, Welham, & McGrath, 2007), primarily due to cardiovascular disease (Janssen, McGinty, Azrin, Juliano-Bult, & Daumit, 2015; Newcomer & Hennekens, 2007; Osborn et al., 2008), produces social costs exceeding $300 billion per year (Insel, 2008), and is the largest and fastest growing subgroup of social security disability beneficiaries (Drake, Frey, Bond, & Al, 2013; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2010). This population often has significant health and social service needs that require navigating disconnected systems of care. Policymakers and clinicians are increasingly recognizing the challenges posed by this segregated structure. A number of efforts, including recent initiatives led by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (Scharf et al., 2013) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Peek & The National Integration Academy Council, 2013; The Academy Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care, 2017) as well as new models introduced under the Affordable Care Act (e.g., Medicaid health homes, accountable care organizations) are underway to promote a more integrated delivery system (Bao, Casalino, & Pincus, 2012; Crowley & Kirschner, 2015).

Although research points to the promise of integrated care for persons with SMI (Bradford, Cunningham, Slubicki, Mcduffie, & Kilbourne, 2013; Druss et al., 2010; Druss & von Esenwein, 2006; Gilmer, Henwood, Goode, Sarkin, & Innes-Gomberg, 2016; Kwan & Nease, 2012; Reilly et al., 2013; Scharf et al., 2013), there is little consensus on what constitutes integrated care (Kwan & Nease, 2012). Integration is an abstract, multi-dimensional concept and each component of an integrated care model may have varying levels of influence on outcomes of interest, including delivery of evidence-based care and consumer health. Use of a common language to describe integration models and standardized measures for assessing provider and health system success in achieving integrated care are in nascent stages.

To address these barriers to advancing integration, in 2013, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published the “Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration”(Peek & The National Integration Academy Council, 2013). This lexicon addresses the inconsistency in concepts and definitions related to integrated care. It includes three defining clauses, which delineate how an arrangement qualifies as genuinely integrated care; these clauses connect to seven parameters, which provide a vocabulary for distinguishing the dimensions by which integrated care models differ (e.g., type of collaboration, spatial arrangement). These parameters are not themselves measures of integrated care but rather provide a foundation for developing metrics to assess integrated care.

In this study, our aim was to use data collected from providers participating in a Maryland state-wide reform aiming to integrate behavioral health, somatic care, and social services for adult Medicaid enrollees with SMI to develop preliminary measures that operationalize the parameters in AHRQ’s lexicon. Under the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid health home state plan option, Maryland, 17 other states and the District of Columbia (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), 2017b) developed and implemented models to improve the integration of services for Medicaid enrollees with SMI (Bao et al., 2012). States received an enhanced federal matching rate (90%) during the first two years of the program. After this period of enhanced matching ended, Maryland opted to continue its health home program. In Maryland, health homes are located in psychiatric rehabilitation programs (PRPs), which provide psychosocial support, life skills training, case management, and social services for individuals with SMI. Staffing requirements for the Maryland health homes include a health home director, nurse care manager (registered nurse or nurse practitioner), and primary care consultant (physician or nurse practitioner). Participating providers receive a set monthly rate (increased from $98.87, the initial rate, to $102.86 on July 1, 2017) for the intake month and each subsequent month during which the enrollee receives at least two health home services (Maryland Department of Health, 2017). Reimbursable health home services include comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional and follow-up care, patient and family support, and referral to community and social support services (Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2013).

Using the Maryland Medicaid health home as a case study for developing integration measures offers several benefits. First, this model aims to integrate not only behavioral and somatic health care but also social services. Increasingly, policymakers are interested in health systems that take into account the social determinants of health (e.g., Accountable Health Communities) (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), 2017a). The measures presented in this study are suited to assessing dimensions of this more expansive integration approach than models focused solely on the integration of behavioral health and primary care. Second, the Maryland health homes are structured as “reverse integration” models in which primary care is integrated into the behavioral health setting (Bao et al., 2012; Shackelford, Sirna, Mangurian, Dilley, & Shumway, 2013). With the exception of initiatives funded under SAMHSA’s Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration grant program, most integration models to-date (e.g., the collaborative care model, patient-centered medical home) have involved adaptations within the primary care setting to accommodate behavioral health (Bao et al., 2012; Woltmann et al., 2012). While these more traditional models may be appropriate for individuals with less severe mental disorders, they are arguably less well-suited for the SMI population, for whom behavioral health providers are typically the principal points of contact with the broader health care system (Alakeson, Frank, & Katz, 2010; Bao et al., 2012).

Other efforts to construct integration measures based on the AHRQ lexicon have resulted primarily in the development of composite measures of integration, i.e. a single integration score aggregating integration across multiple dimensions (Kessler, 2015; The Academy Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care, 2017). No research of which we are aware has operationalized the AHRQ lexicon to develop measures of the various dimensions of integrated somatic, behavioral, and social services for people with SMI. Characterizing integration across distinct dimensions serves several purposes unaddressed by composite integration measures. These measures can help organizations characterize their integrated service delivery across multiple dimensions, for example spatial arrangement (e.g. co-located services) and care team expertise (e.g. a team in place with behavioral, somatic, and social service expertise). Full integration on all dimensions may not be feasible for all organizations; for instance, some organizations may not have the physical space needed to co-locate all providers and need to invest in other approaches, such as facilitating transportation or building an infrastructure to improve provider coordination. Strategies for implementing evidence-based services may need to differ depending upon level of integration, making accurate characterization of integration dimensions an important implementation planning tool. In addition, moving forward, such measures enable researchers to assess whether specific dimensions of integration initiatives are more or less influential in improving delivery of evidence-based care and consumer outcomes.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

We surveyed one health home leader representing each of 46 of 48 (response rate: 96%) Maryland PRP health home sites that were active at the time of data collection (November 2015 – December 2016). Some leaders were responsible for more than one health home program within their umbrella organization; we surveyed a total of 41 leaders representing the 46 sites. At each organization, we asked organization or program directors to identify the person most familiar with health home implementation and recruited that individual for the survey using a combination of email and phone recruitment. The 41 survey participants included health home directors (n=9), nurse care managers (n=7), administrators or division directors (n=14), e.g., directors of integrated care, a health home primary care consultant, and a health home administrative support staff person, all of whom were identified as having intimate knowledge of and involvement in the day-to-day operations of the health home and its implementation.

Respondents provided signed consent and then completed surveys on a tablet via Qualtrics Survey Software (Qualtrics, 2005) at their organization with at least one study team member present to answer respondents’ clarifying questions. Median survey duration was 42 minutes (range: 13–107 minutes). The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Sheppard Pratt Institutional Review Boards.

Survey and Measures

The survey (Appendix A) consisted of five modules containing 110 survey items. The survey modules focused on: health home services; implementation strategies; affiliation and spatial arrangement; type of collaboration employed; and health home enrollee information. We developed original survey questions to elicit information that could be used as inputs in algorithms to operationalize the parameters described in the AHRQ lexicon. For example, to collect information about the information-sharing strategy employed across providers involved in caring for health home enrollees, we asked respondents to report on the frequency with which they notified other providers about changes in a health home enrollee’s status, the frequency with which other providers notified the health home provider about changes in the enrollee’s status, the frequency of regularly scheduled in-person, telephone, or online meetings with other providers, use of communication and electronic notification systems for informing partner providers about health home enrollee’s status, and similar questions (see Appendix A for the full list of questions). We piloted the questionnaire in two health home sites before fielding it more widely. One study team member (K-H) drafted the initial algorithms using these survey responses as inputs. The full study team reviewed the algorithms and the measures produced by these algorithms for face validity. In addition, the team discussed how well the measures mapped onto the AHRQ parameters and the extent to which the measures reflected variation across the health homes. The algorithms underwent several iterations based on this process of study team review and discussion. The algorithms (Appendix B) generated three to four-category ordinal variables with values ranging from no to minimal integration (coded one) to high level of integration (coded three or four) for each dimension measured. In total, we developed nine measures of specific integration dimensions: range of care team (1) functions and (2) expertise; (3) spatial arrangement across providers; (4) information-sharing strategies employed across providers; (5) consumer engagement; (6) health data access; (7) social data access; (8) care plan comprehensiveness; and (9) systematic consumer follow-up. Table 1 displays how our measures map onto AHRQ’s parameters. See Appendix B for the full details of the algorithms used to construct the measures.

Table 1.

Integration measures derived from AHRQ parameters

| Original AHRQ Parameter | Measures Developed for the Present Study |

|---|---|

1. Range of care team function and expertise that can be mobilized to address needs of particular patients and target populations:

|

1. Range of care team functions

|

2. Type of spatial arrangement employed

|

3. Spatial arrangement of each provider type with the health home: primary care providers; mental health providers; substance use treatment providers; supported housing staff; supported employment staff (5 sub-measures)

|

3. Type of collaboration employed

|

4. Communication and information-sharing strategies employed by health home with each provider type: PRP staff; primary care providers; mental health providers; substance use treatment providers; supported housing staff; supported employment staff; criminal justice staff (7 sub-measures)

|

| 4. Method for identifying individuals who need integrated behavioral health and medical care | Not applicable to the health home setting; all Medicaid beneficiaries participating in psychiatric rehabilitation programs were eligible |

5a. Protocols in place or not for engaging patients in integrated care

|

5. Consumer engagement protocols

|

6a. Proportion of patients in target groups with shared care plans

|

6. Access to consumer health data

|

7. Level of systematic follow up

|

9. Systematic follow-up of consumers

|

Notes: AHRQ parameters are from: Peek CJ and National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration. April 2013. AHRQ Publication No AHRQ-13-IP001-EF. Accessible: https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf

Range of care team functions and expertise

AHRQ’s first parameter is the range of care team function and expertise that the integrated practice can mobilize to address needs of the target population. Rather than combining the concepts of function and expertise, we constructed two measures which assess each of these separately. Health homes with foundational care team functions and expertise were those meeting the minimum requirements established by the state of Maryland in terms of the functions of the health home care team and the staffing positions they must fill (expertise). Health homes with foundational plus or extended functions or expertise were those fulfilling additional functions (e.g., medication management, tracking lab tests) or including staff with more expansive expertise (e.g., substance use treatment providers, social workers) beyond the minimum state requirements. These foundational plus and extended functions and expertise categorizations reflect distinctions included in the corresponding AHRQ parameter.

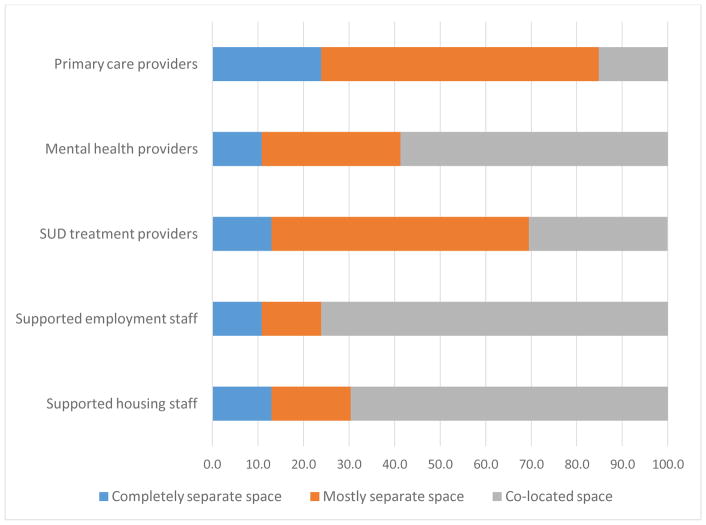

Spatial arrangement across providers

We operationalized AHRQ’s spatial arrangement parameter to capture arrangements that fell short of co-location of health home and other providers within the same building but nevertheless involved sufficient geographic proximity for consumers to walk or obtain health home-provided transportation to visit these other providers. We constructed separate measures for spatial arrangement of the health home with five other types of providers: primary care; mental health; substance use treatment; supported employment; and supported housing.

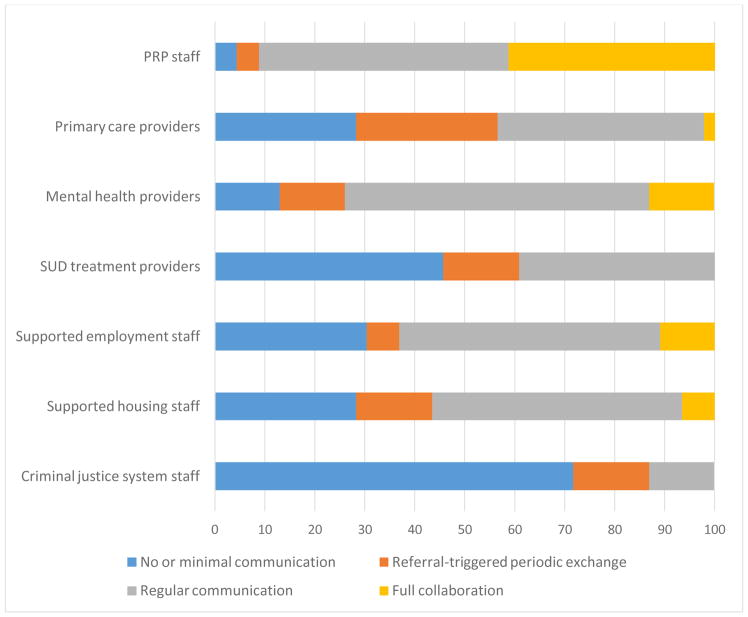

Information-sharing strategies employed across providers

To assess type of collaboration employed, we focused on information-sharing between the health home and seven other types of providers, including: primary care; mental health; substance use treatment; supported employment; supported housing; psychiatric rehabilitation program staff; and criminal justice system. We examined information-sharing, but not spatial arrangement, with psychiatric rehabilitation program and criminal justice system staff because in Maryland, all health homes are located within psychiatric rehabilitation programs and criminal justice system staff are located externally. Measures described the degree to which these providers engaged in a mutual exchange of information about consumers (e.g., reciprocal notification of changes in enrollees’ status), had regularly scheduled meetings, or used additional strategies for keeping up-to-date on changes to consumer needs and care (e.g., messaging systems).

Consumer engagement

AHRQ’s fifth parameter includes two sub-parameters: whether or not the practice has protocols in place for engaging the target group and the proportion of the target population for whom these protocols are followed. Our measure focused on whether the health home had developed materials to facilitate consumer engagement (e.g., printed materials, electronic support tools for guiding care).

Data access and care plan comprehensiveness

AHRQ’s sixth parameter also includes two sub-parameters that involve measuring the proportion of the target population with shared care plans and the proportion for whom the care plans were implemented and followed. We developed three measures related to care plans. Two measures assessed the degree of access that health home staff had to key data related to consumers’ health (health data access) and socioeconomic characteristics (social data access) given that these data are critical to developing complete and accurate care plans. We also constructed a measure of the comprehensiveness of consumers’ care plans based on the type of information health homes typically included in these plans.

Systematic consumer follow-up

Finally, to operationalize AHRQ’s seventh parameter, we measured systematic follow-up of consumers by determining whether or not the health home monitored and adjusted care plans at least twice annually. AHRQ specified one additional parameter, identifying individuals in need of integrated care, which we did not operationalize given its lack of relevance to our case study as all Medicaid enrollees in PRPs are eligible for the health home.

Analysis

For each measure, we calculated the proportion of health homes falling within each category. To assess the strength of correlation between the measures, we generated a polychoric correlation matrix (Appendix C) (UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education, 2017). A secondary analysis included an exploratory factor analysis to determine whether the measures might represent underlying latent variables, potentially enabling further refining of the key dimensions of integration driving the measures we developed and possible information condensation through the development of scales or some other composite variables (Appendix D).

Results

Among the 46 health home programs assessed, we found substantial variability in the level of integration achieved across the dimensions measured. Range of care team functions and expertise: Table 2 displays health homes’ care team functions and expertise. Although most health homes (85%, n=39) reported having the foundational functions expected by the state (e.g., initial evaluation, regular monitoring and adjustment of care plans, population health management), nearly a third of health homes (30%, n=14) lacked the key health home staff (e.g., director, nurse care manager, primary care consultant) required by the state at the time of data collection.

Table 2.

Range of care team functions and expertise, N=46

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Care Team Functions | Care Team Expertise | |

|

| ||

| Lacks foundational functions | 4 (8.7%) | 14 (30.4%) |

| Foundational functions | 3 (6.5%) | 12 (26.1%) |

| Foundational plus | 9 (19.6%) | 15 (32.6%) |

| Extended functions | 30 (65.2%) | 5 (10.9%) |

Notes: Foundational functions and care team expertise encompass minimum state expectations. Foundational plus functions include at least two additional functions (e.g., medication management, tracking lab tests and following up). Extended functions include use of shared EMRs to guide care and integration of health behavioral interventions (e.g., smoking cessation). Foundational plus care team expertise includes psychiatric rehabilitation staff and mental health counselor or psychiatrist. Extended care team expertise includes representation from at least two additional groups (e.g., social worker, substance use treatment provider).

Spatial arrangement across providers

Few health homes reported spatial arrangements in which they operated completely separately from other providers of health and social services for persons with SMI (Figure 1). The largest proportions of health homes had co-located supported employment (76%, n=35) and supported housing (70%, n=32), which are social services frequently provided in PRP settings. Over half (59%, n=27) also had co-located mental health providers, but less than a third (30%, n=14) had co-located substance use treatment providers. Co-location with primary care providers was uncommon with only 15% (n=7) of health homes reporting this type of spatial arrangement. Nearly a quarter of health homes also reported that their location was not within walking distance of primary care providers and that they offered no health home-facilitated transportation to these providers.

Figure 1. Spatial arrangement across providers, N=46.

Notes: Mostly separate space encompasses PRP health home in which the other provider type is located in a different building to which consumers are able to walk or the PRP health home provides transportation. Co-located space indicates that the provider type is located in the same building as the PRP health home.

Information-sharing strategy employed across providers

Forty-one percent of health homes (n=20) reported having monthly or more frequent meetings (in-person, by phone, or online) with the primary care providers serving their health home enrollees (Figure 2). Over a quarter of health homes (28%, n=13) reported having no mutual exchange of information with primary care providers, although an explicit goal of Maryland’s health home model has been to improve coordination between the behavioral health and general medical system. Communication and information-sharing was most limited with substance use treatment providers, with 46% (n=21) of health homes reporting no mutual exchange of information with these providers, and with criminal justice system contacts, with whom 72% (33) of health homes reported no information exchange.

Figure 2. Information-sharing strategy employed across providers, N=46.

Notes: Referral-triggered period exchange refers to occasional notification of changes in consumer status between two provider types. Regular communication refers to regularly scheduled meetings between health home and provider type. Full collaboration refers to an infrastructure and workflow that facilitates regular communication and coordination.

Consumer engagement

The degree to which health homes established protocols for engaging consumers in integrated care varied substantially (Table 3). A third only conducted an initial evaluation of consumer needs (33%, n=15) whereas the remaining two-thirds (n=31) also developed standardized materials, such as a program manual, to guide consumer care. We considered health homes’ access to consumers’ health and socioeconomic characteristics and care needs (Table 4). Health and social data access: Over 80% (n=37) of health homes had at least moderate access to data on consumers’ socioeconomic characteristics and nearly 65% (n=26) had a similar level of access to consumers’ health data. The latter requires cooperation from external medical providers. Care plan comprehensiveness: Nearly half of health homes (46%, n=21) reported having care plans that lacked details on somatic and behavioral health treatment, social services, consumer preferences and goals, with the remaining health homes reporting care plans that encompassed information on all these issues (n=25). Systematic consumer follow-up: The large majority (87%, n=40) of health homes reported regularly monitoring and adjusting care plans and following up on tests and referrals.

Table 3.

Consumer engagement, N=46

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| No or limited protocols in place to engage consumers | 15 (32.6%) |

| Moderate level of protocols in place to engage consumers | 14 (30.4%) |

| Significant protocols in place to engage consumers | 17 (37.0%) |

Notes: Limited protocols in place indicates only an initial evaluation of consumer needs. Moderate level of protocols in place indicates an initial evaluation of consumer needs as well as a program manual or pocket guide to guide consumer care. Significant protocols in place indicates use of electronic decision support tools to guide consumer care.

Table 4.

Data access, exchange and consumer follow-up

| Access to consumer data1 | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Health Data | Social Data | |

|

| ||

| No or very limited access to consumer data | 5 (11.4%) | 4 (9.1%) |

| Limited access to consumer data | 13 (29.6%) | 3 (6.8%) |

| Moderate access to consumer data | 17 (38.6%) | 19 (43.2%) |

| Full access to consumer data | 9 (20.5%) | 18 (40.9%) |

|

| ||

| Care plan comprehensiveness | N (%) | |

|

| ||

| No comprehensive care plan for consumers | 2 (4.4%) | |

| Care plan present but limited in scope | 19 (41.3%) | |

| Care plan for consumers - multi-component | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Care plan for consumers - extended components | 20 (43.5%) | |

|

| ||

| Systematic consumer follow-up | N (%) | |

|

| ||

| No monitoring of care plans | 0 (0.0%) | |

|

| ||

| Monitoring and adjustment of care plans at least twice/year | 6 (13.0%) | |

|

| ||

| Tracking tests, referrals and following up | 40 (87.0%) | |

Notes: Multi-component care plans include plans for physical health treatment, social services, participant goals and/or preferences, and plans for mental health treatment or substance use disorder treatment. Extended components category requires at least five additional components in care plan (e.g., plans for health behavior change, barriers to consumer goas, etc.).

Results limited to respondents who reported being directly involved in managing or delivering clinical care (N=44).

All of the integration measures we developed were at least moderately correlated (i.e., polychoric correlations between 0.3 and 0.5) with at least one other measure (Appendix C). Most of the measures also had strong correlations (>0.5) with at least one another measure. Several of the provider-specific measures of spatial arrangement and type of information-sharing strategy employed were strongly correlated (>0.5), indicating that the degree of spatial proximity and communication and collaboration may be mutually reinforcing. Measures of access to consumers’ health and social data were strongly correlated with systematic follow-up. These measures, however, were not strongly correlated with the comprehensiveness of the health homes’ care plans, despite the fact that care plans would likely require these data to be comprehensive.

The exploratory factor analysis did not indicate that particular sets of measures might be driven by the same underlying latent variables (Appendix D). While individual measures were correlated, as noted above, in few instances did multiple measures load onto the same the factors, limiting our ability to group the measures into meaningful higher-level categories.

Discussion

In this study, we operationalized the integrated care parameters described in AHRQ’s Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration (Peek & The National Integration Academy Council, 2013) in the context of the Maryland Medicaid health home initiative, designed to integrate behavioral, somatic, and social services for people with SMI. These preliminary measures build on prior work in several ways. Whereas most existing measures have focused on integration of primary care and mental health services (Center for Evidence-Based Practices at Case Western Reserve University, 2010; Gilmer et al., 2016; Kessler, 2015; Scharf et al., 2013; The Academy Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care, 2017), the nine measures developed in this study accommodate a more expansive model of integration by incorporating behavioral health, somatic, and social services. In addition, these measures were developed for and applied to a “reverse integration” context in which somatic healthcare services are incorporated into a behavioral health setting (Bao et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Finally, rather than generating a composite measure of integration, these measures describe distinct dimensions of integration, each of which may be differentially important in its impact on delivery of evidence-based care and consumer outcomes. The data collection required to measure these dimensions of integration was feasible. Maryland’s Medicaid health home program is unique in that it is the only such program being implemented in PRPs, which, unlike many clinical settings, focus on integrating a variety of social services into consumers’ care. Thus, adaptation of the measures developed in this study to other integrated service models may involve removing survey items (e.g., collaboration with supported housing) not relevant to the types of providers and services involved.

The measures developed in this study yielded useful insight about how Maryland PRPs have implemented integrated care in their health home programs. Results showed considerable variation in the degree of integration achieved across dimensions between and within health home sites. Findings suggest that health homes have struggled to build care teams with a wide breadth of expertise; in fact, a substantial minority (30%) faced challenges meeting the state’s minimum requirements for staffing. On the other hand, the majority of health homes reported care teams that function at high levels. This may be an indication that health home functions can be successfully fulfilled with a more flexible staffing arrangement than the one required by the state.

To date, little is known about which integrated care dimensions are associated with improved delivery of evidence-based services and consumer outcomes, particularly among the population with SMI. However, the limited prior research provides some insight into how the dimensions of integration achieved in Maryland Medicaid health homes may influence service delivery and consumers’ health. With respect to spatial arrangement, few health homes reported having providers on-site that were not already part of their standard psychiatric rehabilitation programming, such as primary care or substance use treatment providers. The extent to which this signals insufficient integration is unclear. Prior studies suggest that co-location may be beneficial in promoting collaboration and communication among providers responsible for caring for the same population and in improving consumer receipt of needed care (Craven & Bland, 2006; Kwan & Nease, 2012; Scharf et al., 2013). Notably, we did find moderate-to-high levels of correlation between the spatial arrangement and information-sharing measures. Yet, an exploratory factor analysis found minimal evidence that an underlying latent variable may be driving variance in the spatial arrangement and information-sharing measures, beyond those for the key social services offered by many psychiatric rehabilitation programs, supported housing and employment. On the other hand, a study comparing co-located care to enhanced referral to off-site specialty care among older adults found that while co-located care may increase receipt of needed services, clinical outcomes were similar among the two groups and enhanced referral actually outperformed co-location among the subset of adults with major depression (Kwan & Nease, 2012).

Communication and interaction among providers are associated with improvements in consumer outcomes (Kwan & Nease, 2012). However, less than half of health homes reported regular communication with primary care and substance use treatment providers, despite the fact that enhanced communication with primary care, in particular, is a focus of Maryland’s Medicaid health home initiative. Similarly, research shows that having access to complete data on a population may improve providers’ ability to identify and address consumer needs, such as gaps in benefits coverage (Rosenheck, Frisman, & Kasprow, 1999). Yet health homes generally reported more limited access to consumers’ health data than data on their socioeconomic characteristics and needs, suggesting that they are having difficulty obtaining needed health data (e.g. updated lab results) from external providers.

Challenges coordinating care between health home and external medical providers may be due in part to the nature of health home reimbursement. While health home providers are reimbursed for their time spent coordinating care for consumers with SMI, the primary care and other providers in the community who health home providers are attempting to connect with are not reimbursed for their time. This lack of financial incentive may impede external providers’ capacity and inclination to invest in communication and data- and information-sharing with health homes. Leveraging the information that most health homes already have (e.g., rich data on socioeconomic characteristics of consumers and their social service needs) may be one avenue for persuading somatic care providers to engage in mutual exchange of information. The Institute of Medicine has recommended that electronic medical records include data on social determinants of health and efforts are underway to support providers serving vulnerable populations, such as community health centers, in collecting and incorporating this type of information into their records (Gold et al., 2017).

In addition to capturing social data, most health homes reported systematic follow-up of consumers. Other research has found that systematic follow-up is related to improved clinical outcomes among individuals with depression enrolled in collaborative care models (Craven & Bland, 2006).

The inferences we can draw from prior research on the relative importance of different dimensions of integrated care is limited. Given the heterogeneity among the health homes in Maryland across the dimensions measured, future research should examine the relationship between these integration measures and consumers’ receipt of evidence-based services and health and social outcomes. This research would provide policymakers, health system administrators, and providers with a clearer sense of where to direct limited resources as they implement these types of integrated care models. Understanding which dimensions of models designed to integrate delivery of behavioral, somatic, and social services for people with SMI lead to improved outcomes could also inform the development of evidence-based criteria for accreditation of such models, similar to the NCQA’s patient centered medical home (PCMH) accreditation criteria for primary care practices (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2017).

This study has several limitations. First, we did not formally assess the validity and reliability of the measures developed. Our objective was to develop preliminary measures that can be validated in future research. Next steps involve linking these measures to quality indicators derived from Medicaid claims data in order to determine whether particular measures are associated with changes in quality of care pre-post health home implementation. Second, the context in which these measures were developed is somewhat unique. Maryland is the only state in the country implementing health homes in psychiatric rehabilitation programs. Although Maryland ranks fairly highly nationwide on several different rankings of state mental health system infrastructures (Aron, Honberg, Duckworth, & et al, 2009; Mental Health America, 2017; National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2014), among other states implementing health homes targeting populations with SMI, it generally falls within the middle to lower top-half (Appendix E). This suggests that the state is not so unique in terms of its mental health system to prevent measures derived from its experiences being potentially useful and generalizable to other states. The algorithms and measures developed in this study were designed to be adaptable to other types of providers and services. For instance, the types of providers for which we calculated measures of spatial arrangement and information-sharing with the health home can be substituted with other types of providers in different contexts. In addition, measures of integration were collected through surveys of implementation leaders. Some dimensions measured, e.g. comprehensiveness of care plans and frequency of communication with external providers, were not directly observed by our research team and could be subject to reporting bias. In addition, measures of integration assessed type and frequency of interactions among providers, delivery of consumer services, and presence of a protocol for engaging consumers in care, but did not assess the quality of these strategies.

Conclusion

By operationalizing AHRQ integration parameters, this study advances development of standardized methods for characterizing integrated care models. While integrated care continues to be promoted as a solution to the health challenges facing vulnerable populations with complex health and social challenges, such as those with SMI, it is not clear which dimensions of integrated care models are most critical to achieving improvements in delivery of evidence-based care and consumer health. The measures presented in this study are a first step toward supporting research identifying the key components of integrated care models targeting people with SMI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. R24MH102822 (PI: Daumit) and K01MH106631 (PI: McGinty).

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been presented at any meetings or conferences.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (#00072673) and the Sheppard Pratt Institutional Review Board (#810701-2). All data was collected in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Signed informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Alene Kennedy-Hendricks, Assistant Scientist, Department of Health Policy and Management, Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Gail L. Daumit, Professor, Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Departments of Health Policy and Management and Mental Health and the Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Seema Choksy, Senior Research Analyst, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Sarah Linden, Senior Research Analyst, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

Emma E. McGinty, Assistant Professor, Departments of Health Policy and Management and Mental Health and the Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N. Broadway, Hampton House 359, Baltimore, MD 21205.

References

- Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty Care Medical Homes For People With Severe, Persistent Mental Disorders. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):867–873. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron L, Honberg R, Duckworth K, et al. Grading the States 2009: A Report on America’s Health Care System for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. 2009 Retrieved February 1, 2018, from https://www.nami.org/grades.

- Bao Y, Casalino LP, Pincus HA. Behavioral Health and Health Care Reform Models: Patient-Centered Medical Home, Health Home, and Accountable Care Organization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;40:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford DW, Cunningham NT, Slubicki MN, Mcduffie JR, Kilbourne AM. An evidence synthesis of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness: A systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):e754–e764. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Evidence-Based Practices at Case Western Reserve University. Integrated Treatment Tool. Cleveland, OH: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.centerforebp.case.edu/resources/tools/integrated-treatment-tool. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Accountable Health Communities Model. 2017a Retrieved July 5, 2017, from https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicaid Health Homes: SPA Overview. 2017b Retrieved February 1, 2018, from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/medicaid-state-technical-assistance/health-homes-technical-assistance/downloads/hh-spa-overview.pdf.

- Craven MA, Bland R. Better practices in collaborative mental health care: an analysis of the evidence base. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51(6 Suppl 1):7S–72S. Retrieved from www.ccmhi.ca. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley RA, Kirschner N. The integration of care for mental health, substance abuse, and other behavioral health conditions into primary care: Executive summary of an American college of physicians position paper. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163(4):298–299. doi: 10.7326/M15-0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake R, Frey W, Bond G, Al E. Assisting Social Security Disability Insurance beneficiaries with schizophrenia, bipolard disorder, or major depression in returning to work. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1433–1441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, von Esenwein Sa. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):151–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Henwood BF, Goode M, Sarkin AJ, Innes-Gomberg D. Implementation of Integrated Health Homes and Health Outcomes for Persons With Serious Mental Illness in Los Angeles County. Psychiatric Services. 2016;(13) doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500092. appi.ps.2015000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce A, Middendorf M, Hollombe C, Cowburn S, … Melgar G. Developing Electronic Health Record (EHR) Strategies Related to Health Center Patients’ Social Determinants of Health. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2017;30(4):428–447. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T. Assessing the Economic Costs of Serious Mental Illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):663–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen EM, McGinty EE, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Review of the evidence: Prevalence of medical conditions in the United States population with serious mental illness. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2015;37(3):199–222. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. Evaluating the process of mental health and primary care integration: The Vermont Integration Profile. Family Medicine and Community Health. 2015;3(1):63–65. https://doi.org/10.15212/FMCH.2015.0112. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan BM, Nease DE. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care. In: Talen M, Valeras AB, editors. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care: Evaluating the Evidence, Identifying the Essentials. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2012. pp. 65–98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis VA, Colla CH, Tierney K, Van Citters AD, Fisher S, Meara E. Few ACOs pursue innovative models that integrate care for mental illness and substance abuse with primary care. Health Aff. 2014;33(10):1808–1816. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of Health. Title 10: Subtitle 09 Medical Care Programs. Maryland Register. 2017 Retrieved from https://health.maryland.gov/regs/Pages/10-09-33-Health-Homes-(MEDICAL-CARE-PROGRAMS).aspx.

- Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Health Homes: 2013 Provider Manual. Baltimore, MD: 2013. Retrieved from http://dhmh.maryland.gov/bhd/Documents/HealthHomesManualAugust2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health America. Access to Care Map. 2017 Retrieved February 1, 2018, from http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/issues/ranking-states.

- National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. State Mental Health Agency - Controlled Expenditures for Mental Health Services, State Fiscal Year 2013. 2014 Retrieved February 1, 2018, from https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment10 - Expenditures.pdf.

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition - 2017 Standards Preview. Washington, DC: 2017. Retrieved from http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Programs/Recognition/PCMH/2017 PCMH Concepts Overview.pdf?ver=2017-03-08-220342-490. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(15):1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature Mortality Among Adults With Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172–81. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, King MB, Deo R, Nazareth I. Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illnesses: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-84. https://doi.org/1471-244X-8-84 [pii]\r10.1186/1471-244X-8-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek CJ The National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration. Rockville, MD: 2013. Retrieved from https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics Survey Software. Provo, UT: 2005. Retrieved from www.qualtrics.com. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, Hann M, Knowles S, Druss B, Lester H. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;11(11):CD009531. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009531.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Kasprow W. Improving access to disability benefits among homeless persons with mental illness: an agency-specific approach to services integration. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(4):524–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.4.524. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10191795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in individuals with schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Eberhart NK, Hackbarth NS, Horvitz-Lennon M, Beckman R, Han B, … Burnam MA. Evaluation of the SAMHSA Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) Grant Program: Final Report. Santa Monica, CA: 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford JR, Sirna M, Mangurian C, Dilley JW, Shumway M. Descriptive analysis of a novel health care approach: reverse colocation - primary care in a community mental health “health home”. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 2013;15(5) doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Mental Health, United States, 2008. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 10-4590. Rockville, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The Academy Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care. A framework for measuring integration of behavioral health and primary care. 2017 Retrieved June 1, 2017, from https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/resources/ibhc-measures-atlas/framework-measuring-integration-behavioral-health-and-primary-care.

- UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education. How can I perform a factor analysis with categorical (or categorical and continuous) variables? 2017 Retrieved May 1, 2017, from https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stata/faq/how-can-i-perform-a-factor-analysis-with-categorical-or-categorical-and-continuous-variables/

- Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.