Abstract

This study reports a microfluidic device for whole blood processing. The device uses the bifurcation law, cross-flow method, and hydrodynamic flow for simultaneous extraction of plasma, red blood cells, and on-chip white blood cell trapping. The results demonstrate successful plasma and red blood cell collection with a minimum dilution factor (0.76x) and low haemolysis effect. The extracted red blood cells can also be applied for blood type tests. Moreover, the device can trap up to ~1,800 white blood cells in 20 minutes. The three components can be collected simultaneously using only 6 μL of whole blood without any sample preparation processes. Based on these features, the microfluidic device enables low-cost, rapid, and efficient whole blood processing functionality that could potentially be applied for blood analysis in resource-limited environments or point-of-care settings.

Introduction

Blood is composed of plasma, red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets, and it contains numerous types of physiological and pathological information about the human body. Currently, complete blood count (CBC) is one of the most common blood tests. The test shows the count of each cell type, cell sizes, the fraction of specific cells in whole blood, and the concentration of various proteins, creatinine, or metabolites. The test gives an overview of patients’ health status1,2. For sophisticated CBC analysis, automated haematology analysers and flow cytometers are the most common instruments in hospitals or laboratories. For molecular-level detection, lysed blood cells are drawn into a cuvette for spectrophotometric measurement. Achieving precise CBC measurements usually requires efficient and high-quality processes for the collection and preparation of whole blood samples to avoid any background interference, including centrifugation, fractionation, lysis, or dilution3. For example, improper centrifugation could lead to haemolysis, resulting in plasma contamination. Therefore, conventional blood tests are usually time-consuming and require a large volume (~millilitre) of blood, as well as well-trained staff. These requirements limit the access to blood analysis in environments with limited resources or point-of-care settings.

Microfluidics is an ideal technique to simplify whole blood processing based on the capability of integrating different functional elements and potential automation features. Furthermore, due to its miniature channel size, footprint, the required sample volume can be effectively minimised. A comprehensive review of microfluidics for whole blood processing has been shown in previous literatures3,4. Basically, microfluidics for blood cells or plasma separation can be categorised into active or passive separation methods5–7. Active separation methods exploit external forces (acoustic force8–10, dielectrophoretic force11–13, magnetic force14,15, or combination of above forces16–19) to guide targeted cells to a specific direction or position. Passive separation methods simply use differences in cell properties for cell separation, such as the size, shape, or stiffness.

Generally, active separation methods enable high-throughput, high-selectivity cell separation, which is preferred in the sorting or isolation of rare cells (e.g. circulating tumour cell or bacteria) in large amounts of blood samples. However, the samples usually need to be purified cells or RBCs-lysed blood. The reason is the enormous number of RBCs in whole blood, which limits the efficient trapping of WBCs or rare cells. One exception is using a magnetic force to isolate magnetically-labelled WBCs directly from unprocessed whole blood15. However, magnetically trapped cells accumulate in a specific region with high magnetic field density, which is not ideal for cell counting or single cell analysis.

In contrast, passive separation methods do not require any cell labelling process or sophisticated micro/nano-fabrication, which makes them more cost-effective and adequate for separating blood cells from plasma, or vice versa. For plasma, one simple microfluidic structure uses a micro-trench along the flow path, which can trap blood cells based on sedimentation and enable plasma purification20. Other microchannel geometries for plasma extraction are deterministic lateral displacement (DLD) structures21, curved series microchannels22, and laminar micro-vortices microfluidics23. Another efficient plasma extraction design is using the bifurcation law24–26 (or so-called Zweifach-Fung effect) to guide most RBCs into the main microchannel (higher flow rate), and the plasma can be extracted from the side microchannel (lower flow rate)27. A similar design uses a slightly wider side microchannel to allow both RBCs and plasma to flow in, while WBCs flow downstream of the main channel28. This passive separation mechanism eliminates the complexity of cell labelling. However, the main issue is the lower throughput compared to active separation methods.

Although various microfluidic-based blood cell separation or plasma extraction techniques have been demonstrated, to the best of our knowledge, most methods extract only one kind of blood component by removing or discarding the other components, which limits the detectable parameters in a single whole blood sample. By optimising the bifurcation channel design and adding cellular trapping units, we propose a continuous-flow whole blood processing microfluidic device for isolating multiple blood components. The device contains two types of side channels (with and without packed beads) and a series of hydrodynamic-based WBC trapping units. As a proof of concept, we first measured the absorbance of collected plasma to determine a minimum dilution factor and low haemolysis effect. We then did a blood type test using the extracted RBCs to ensure their characteristics were still well retained29,30. Moreover, we analysed the WBC seeding pattern in trapping units to confirm that efficient WBC trapping is possible. Finally, we successfully demonstrated all whole blood processing functions, including extraction of plasma, RBCs, and WBC trapping can be simultaneously performed in a single microfluidic device. The total assay time was just 20 minutes with only 6 μL of whole blood required. To clearly describe the unique feature of our device, we create a table listing important parameters of existing microfluidics for whole blood processing and our work (Table 1). Based on these features, the microfluidic device shows the potential to be applied for blood analysis in resource-limited environments or point-of-care settings.

Table 1.

A summary of microfluidics for whole blood processing.

| Author | Active/Passive | Mechanism | Label-free | Injected Sample | Sample Volume/ Throughpu | Desired target (# of targets) | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuchao Chen et al.8 | Active | Acoustic | Yes | Whole blood | 10000 μL/min | Platelet (1) | >85% Platelet recovery rate >80% RBC/WBC removal rate |

| Maria Antfolk et al.9 | Active | Acoustic | Yes | Spiked cancer cells in RBC-lysed and 10X diluted whole blood | 100 μL/min | CTC (1) | 91.8% MCF7 separation efficiency 84.1% DU145 recovery rate |

| P. Dow et al.10 | Active | Acoustic | Yes | Spiked bacteria in PBS-diluted whole blood to 20% Hct | 10 μL/min | Bacteria (1) | >85% RBC removal rate.45–60% Bacteria yield |

| Crispin Szydzik et al.11 | Active | Dielectrophoretic | Yes | Whole blood | 15 μL in 15 min | Plasma (1) | 165 nL undiluted plasma |

| Anas Alazzam et al.12 | Active | Dielectrophoretic | Yes | Spike cancer cells in sucrose/dextrose medium resuspended whole blood | 1.67 μL/min | CTC (1) | 95–98% MDA231 separation efficiency |

| Matthew S. Pommer et al.13 | Active | Dielectrophoretic | Yes | ~10X diluted whole blood using LEC buffer | 2.5 μL/min | Platelet (1) | 95% Platelet purity |

| Ki-Ho Han et al.14 | Active | Magnetic | Yes | 10X diluted whole blood using sodium hydrosulfite | 0.083 μL/min | RBC, WBC (2) | 93.5% RBC separation efficiency 97.4% WBC separation efficiency. |

| Macdara T. Glynn et al.15 | Active | Magnetic | No | Spike magnetically-labelled CD4 + cell in whole blood | 4 μL in 15 sec | CD4 + cell (1) | 93.0% CD4 + cell capture efficiency |

| Nezihi Murat Karabacak et al.16 | Active/ Passive | Magnetic + Hydrodynamic | No | Add magnetic beads in whole blood. | 120 μL/min | CTC (1) | 3.8-log depletion of WBC.97% CTC yield. |

| Hye-Kyoung Seo et al.17 | Active/ Passive | Magnetic + Hydrodynamic | Yes | 1000X RBC dilution using PBS | 1000 μL/min | WBC, RBC (2) | 86.8% RBC separation efficiency 29.1% WBC separation efficiency |

| Mahdi Mohammadi et al.18 | Active/ Passive | Dielectrophoretic + Hydrodynamic | Yes | Whole blood mix with 1:1 heparin sodium. | 2 μL in 7 min | Plasma (1) | 100 nL plasma with 99% purity. |

| C. Wyatt Shield IV et al.19 | Active | Acoustic + Magnetic | No | Spike magnetically-labelled LNCaP cancer cell line in RBC- lysed and PBS resuspended whole blood. | 50 μL/min | CTC (1) | 89% LNCaP cancer cell line separation efficiency |

| Ivan K. Dimov et al.20 | Passive | Sedimentation | Yes | Whole blood | 5 μL in 10 min | Plasma (1) | 99.9–100% blood cell retention. |

| John A. Davis et al.21 | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | Whole blood | 0.4 μL/min | Plasma (1) | 100% plasma recovery rate 100% cell removal rate. |

| Siddhartha Tripathi et al.22 | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | Diluted whole blood using sodium chloride to 7–62% Hct. | 500 μL/min | Plasma (1) | 99.5% blood cell removal rate. |

| Elodie Sollier et al.23 | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | 20X diluted blood using PBS. | 100 μL/min | Plasma (1) | 17.8% plasma extraction |

| Sung Yang et al.27 | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | Whole blood | 0.16 μL/min | Plasma (1) | 100% plasma purity 15–25% plasma extraction. |

| Myounggon Kim et al.28 | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | Whole blood | 0.33 μL/min | WBC (1) | 96.9% WBC purity 97.2% WBC recovery rate. |

| This work | Passive | Hydrodynamic | Yes | Whole blood | 0.3 μL/min 6 μL in 20 min | Plasma, RBC, WBC (3) | ~1.5 μL 0.76-fold dilution, low hemolysed plasma, 1200–1800 trapped WBC |

Results and Discussion

Device design

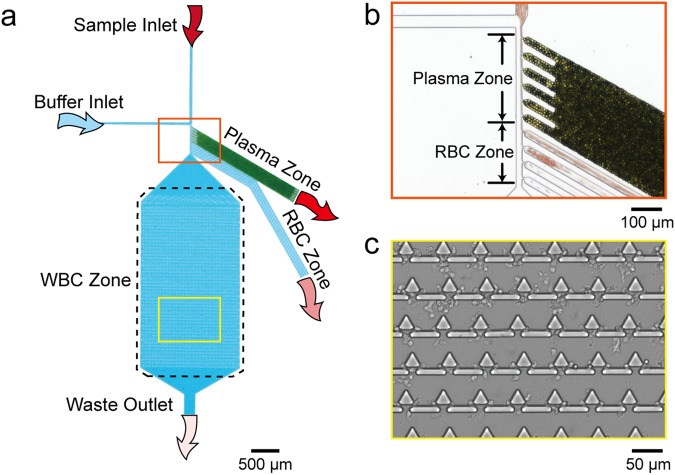

The microfluidic device is composed of a whole blood inlet, buffer inlet, and bifurcation region, which lead to three collection zones for blood components: a plasma zone, RBC zone, and WBC zone. The RBC/WBC separation mechanism is based on the bifurcation law and cross-flow method28. Based on a previous study, a flow rate ratio of 1:10 between the whole blood and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) is ideal for RBC/WBC separation. The bifurcation region contains six bead-packed side channels, four-necked side channels, and one main channel for the extraction of plasma, RBCs, and WBC trapping, respectively. To achieve a uniform flow pattern in the bifurcation region, all side channels were tilted at 60 degrees relative to the main channel31. A schematic of the microfluidic device is shown in Fig. 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the microfluidic device, which contains a whole blood sample inlet and a buffer inlet, respectively. After the whole blood sample flowed to the bifurcation region (orange zone), plasma and RBCs were extracted to plasma zone and RBC zone, respectively. WBCs flowed to the main channel and were trapped in the WBC zone. (b) Photograph of the plasma zone and RBC zone entrance. Green particles are packed beads, and red particles are RBCs. (c) Photograph of the WBC zone with trapped WBCs.

To enable efficient cell separation, the flow pattern of cells needs to be close to the side channel wall of the plasma zone and RBC zone. As shown in Fig. 1b, the whole blood flow pattern is pushed to the side. Typically, RBCs are 6.2~8.2 μm in diameter with 2~2.5 μm in thickness32 and WBCs are 7~18 μm in diameter33. Due to the densely packed 10-μm beads in the side channel, the effective pore size is 1.55 μm. Therefore, all blood cells would pass by and only plasma can flow into the plasma zone and be collected. Smaller-sized RBCs with higher deformability are then squeezed into the channel of the RBC zone with a 2-μm neck. Finally, WBCs passing by the plasma zone and RBC zone flow across the boundary of two flow patterns and are trapped in the trapping units of the WBC zone (Fig. 1c). The trapping unit is a combination of one triangular pillar and two rectangular pillars with a gap of 2.5 μm. The detailed dimensions of the microfluidic device are listed in Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S1.

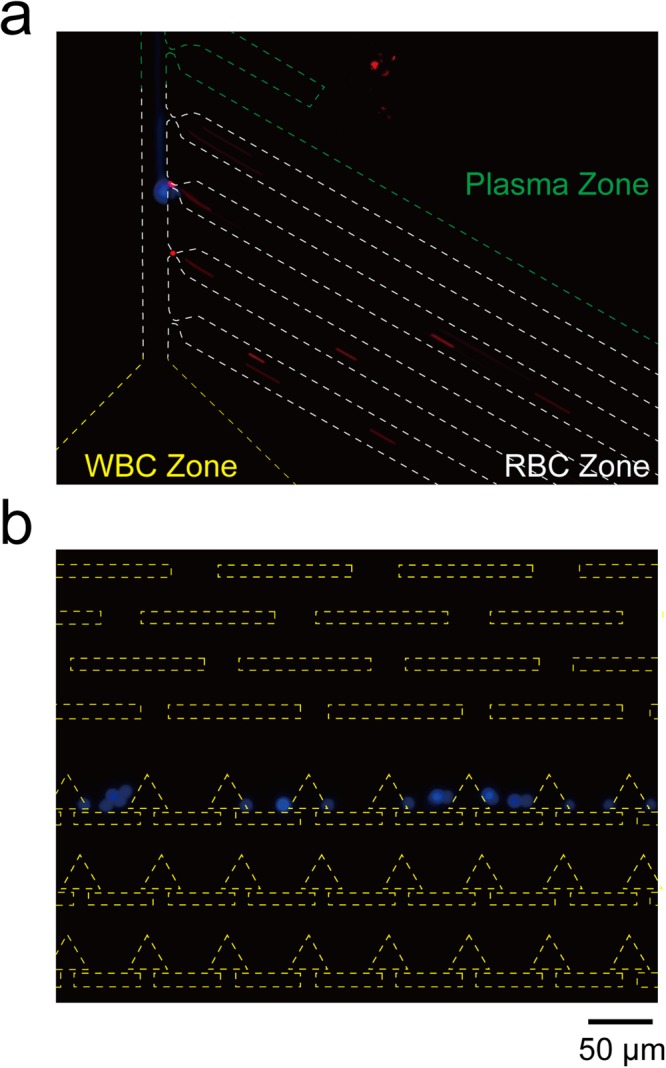

Fluorescent bead simulation

To verify the RBC/WBC separation functionality of the microfluidic device, we first mixed 1.5 × 107 beads/mL of 2-μm red fluorescent beads and 4.5 × 105 beads/mL of 10-μm blue fluorescent beads to mimic RBCs and WBCs. A fluorescence image of the beads in the bifurcation region and the trapping units of the WBC zone is shown in Fig. 2. The green, white, and yellow dashed lines represent the channel walls of the plasma zone, RBC zone, and WBC zone, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2a, most of the 2-μm beads flowed into the RBC zone due to their small size. Although a few 2-μm beads also flowed into the plasma zone, most of them were stopped at the front end and were not collected in the outlet of the plasma zone.

Figure 2.

The fluorescence images of beads in the microfluidic device. Green, white and yellow dashed line represent to the plasma zone, RBC zone, and WBC zone, respectively. (a) Most 2-μm red fluorescent beads flow into the RBC zone; (b) 10-μm blue fluorescent beads flow into the WBC zone.

On the other hand, 10-μm beads passed by the plasma zone and RBC zone and flowed directly into the WBC zone. To smooth the flow pattern, five rectangular pillar rows were placed at the entrance of the WBC zone (Fig. 2b). These pillar rows can also block aggregated cell clusters to prevent any clogging issues in the trapping units. These results show that the bifurcation region design enables successful bead separation, which can be applied for whole blood processing.

Plasma extraction

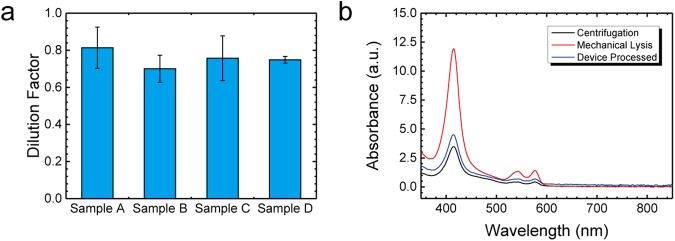

We next tested the plasma extraction using four clinical whole blood samples. To ensure that the extracted plasma can be used for biomarker detection, the plasma needs to have (1) a minimum plasma dilution factor and (2) low haemolysis effect. To find out the plasma dilution factor of the device, we first constructed a standard curve of the absorbance versus the dilution factor using a manually diluted plasma sample. First, we extracted plasma by centrifugation at 500 x g for 10 minutes and diluted it with PBS using five different dilution factors (0.2x, 0.4x, 0.6x, 0.8x, 1x).

We then used a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop One, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA) to measure the 280-nm absorbance intensity of each dilution factor, which correlates to the total protein concentration due to three amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine)34. The protein concentration and composition may vary between different clinical samples, so standard curves of each sample were constructed individually (Supplementary Fig S2). Based on these standard curves, we can then plot the dilution factor of each sample (Fig. 3a). Each sample was processed using three different microfluidic devices. The plasma dilution factors of samples A through D were 0.81x, 0.70x, 0.76x, and 0.75x, respectively. The intra-sample coefficient of variation (CV) was below 16%, indicating a consistent dilution factor in different clinical samples.

Figure 3.

(a) Plot of the dilution factor test in 4 clinical samples. Each sample was processed by 3 individual devices. (b) The UV-VIS spectra of the plasma extracted from centrifugation (black line), the microfluidic device (blue line), and mechanically lysed whole blood (red line).

To confirm the low haemolysis effect during plasma extraction, we compared the UV-VIS spectra of plasma extracted using a standard centrifugation process (black line), the microfluidic device (blue line), and the mechanically lysed whole blood (red line). The haemolysed plasma sample was collected from mechanically lysed whole blood, followed by vortex and centrifugation at 10,000x g for 10 minutes. As shown in Fig. 3b, the presence of haemoglobin would induce characteristic peaks at 41535, 541, and 576 nm36. Instead, the spectra of plasma extracted by the standard centrifugation process and the microfluidic device had very similar intensities and profiles. Overall, these results confirm that the plasma extracted by the microfluidic device has a minimum dilution factor and low haemolysis effect and can be used for the detection of various analytes.

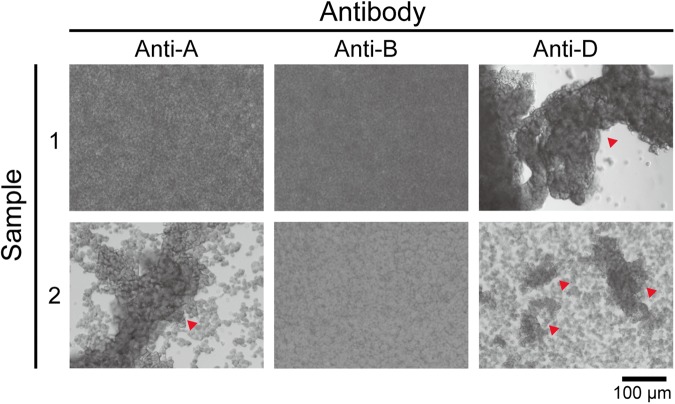

RBC collection for blood type test

Next, we performed a blood type test using RBCs extracted from four clinical samples. First, 10 μL of RBC solution extracted from the RBC zone was injected into polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chambers treated with anti-A, anti-B, and anti-D antibody solutions. The mixed solutions were incubated for 2 minutes and stirred using pipette tips. As shown in Fig. 4, the RBC solution of sample 1 treated with anti-A and anti-B was still turbid, indicating O-type blood. In sample 2, the RBC agglutination (red triangle) can be easily observed in the anti-A-treated RBC solution, but it remained turbid in anti-B treatment, indicating A-type blood. When both sample 1 and 2 were treated with anti-D, the RBC agglutination result indicated that both samples are Rh-positive blood. We used the same method to identify the blood types of sample 3 and 4, and both samples were O-type and Rh-positive blood. A summary is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 4.

Blood type test images from the extracted RBC solutions of blood sample 1 and sample 2 under anti-A, anti-B, and anti-D treatment. The red triangles indicate blood agglutination.

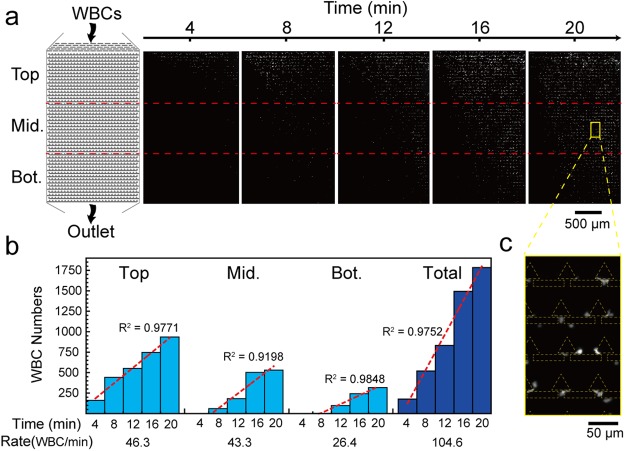

White blood cell trapping

Then, we tested the WBC trapping performance of the microfluidic device. To evaluate the cell seeding pattern, we divided the WBC zone into top, middle, and bottom regions. Each region contains 464 trapping units in the 1-mm x 1.7-mm area. To use all trapping units efficiently and prevent any potential cell clogging issues, we designed a 30-μm gap at the end of each row. Therefore, when trapping units of one row were fully occupied, the following cells could flow through the gap to the next row. Based on this design, we observed that the WBCs were first captured at the top region and gradually successively moved toward the middle and bottom regions.

Figure 5a shows time-lapse fluorescence images of the WBC zone at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 minutes. The images were analysed by Image J software and used to determine the numbers of WBCs in the top, middle, bottom, and overall regions of the WBC zone. As shown in Fig. 5b, the WBCs start to be captured in the top, middle, and bottom regions at t = 0, 6.61, and 7.61 minutes, and the capture rates were 48.3, 43.3, and 26.3 WBCs/min, respectively. There is a similar capture rate in the top and middle regions, indicating that the trapping efficiency would not be affected by preceding cell-occupied trapping units.

Figure 5.

WBC seeding pattern in the trapping units of the microfluidic device. (a) Schematic and time-lapse fluorescence images of WBC zone. (b) Trapped WBC numbers in top, middle, and bottom regions at different time points. The red dashed lines are the regression lines of each region, representing the WBC capture rate. (c) Enlarged image of the yellow box showing the WBC seeding profile.

In contrast, the capture rate in the bottom region was 0.6-times lower than in the top and middle regions. We suspect that the reason is that the trapping units of the top and middle regions were not fully occupied yet. The number of trapped cells in the whole device shows an almost linear curve, indicating a uniform cell seeding pattern. For the whole region, 1,784 WBCs were captured from 6 μL of whole blood with a total capture rate of 104.6 WBCs/min.

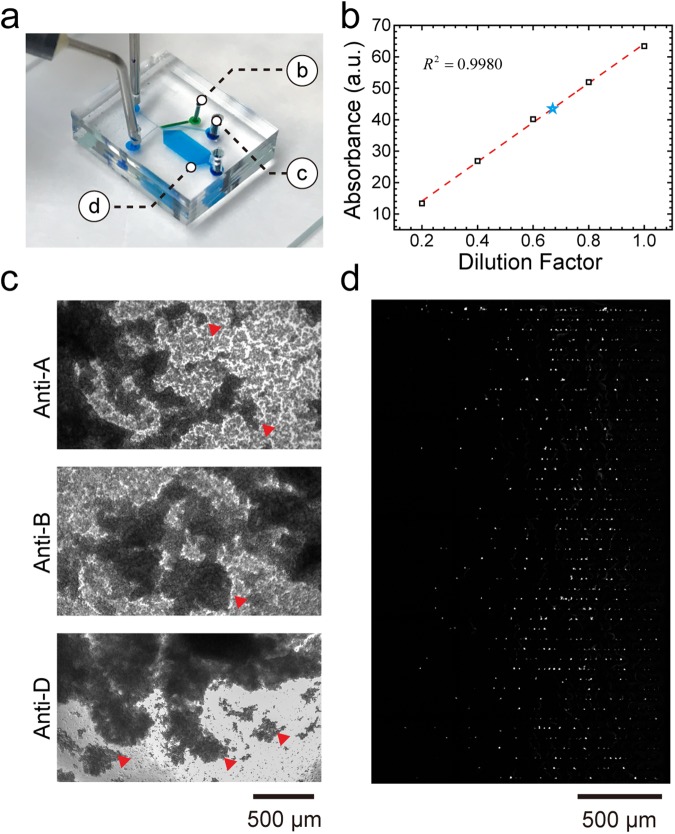

Simultaneous extraction of plasma, RBC and WBC trapping in a single microfluidic device

Finally, we aim to demonstrate the microfluidic device enables the simultaneous extraction of plasma, RBC and on-chip WBC trapping. Same as previous protocols, 6 μL whole blood stained with Calcein AM was loaded into the microfluidic device in 20 minutes. Plasma and RBCs were then extracted from the plasma zone and RBC zone, respectively. In the meantime, WBCs were continuously trapped in the WBC zone. The image of microfluidic device consisted of each zone is shown in Fig. 6a. Once the experiment was done, we then characterized the plasma dilution factor as 0.67x (Fig. 6b) and blood type as AB-type Rh-positive (RBC agglutination in all anti-A, anti-B, and anti-D treatment) (Fig. 6c). As shown in Fig. 6d, WBCs were uniformly seeded in the WBC zone and the total number of trapped WBCs was 1,221, which is similar to the previous test. In summary, all three whole blood processing functions can be performed simultaneously without any interference in a single microfluidic device.

Figure 6.

Simultaneous extraction of plasma, RBCs and on-chip white blood cell trapping. (a) Image of the microfluidic device showing the position of each zone. (b) Standard curve of the absorbance intensity versus dilution factor of manually diluted blood (black rectangles and red dashed line). The blue star represents the absorbance and corresponding dilution factor (0.67x) of extracted plasma in this test. (c) Blood type test images from the extracted RBC solution. The red triangles represent blood agglutination. (d) WBC seeding pattern in the WBC zone.

Conclusion

We have developed a microfluidic device that enables the simultaneous extraction of plasma and RBCs as well as on-chip WBC trapping. The results demonstrated two important features. First, the bifurcation region contains two types of side channels that can extract plasma and RBCs separately. The extracted plasma has a minimum dilution factor (0.755x) and low haemolysis effect. Furthermore, the extracted RBCs can be applied for blood type tests. Second, we added a series of hydrodynamic-based WBC trapping units downstream of the main channel. Based on the carefully designed geometry of the trapping units, the device can trap up to ~1,800 WBCs in 20 minutes. The trapped WBCs could potentially be used for various cellular analyses, such as drug screening, DNA extraction, or cell viability tests. Compared to other existing microfluidic method for whole blood processing, our microfluidic device can directly process extremely low-volume (6 μL) whole blood without any pretreatment (e.g. dilution or lysing), pre-labeling (e.g. fluorophores or magnetic beads conjugation) requirement or external fields (e.g. optical, electrical or magnetic fields) to assist plasma/cell separation. In the future, we aim to further increase the collection throughput of the three blood components. Furthermore, we plan to integrate an automated microfluidic flow control system that has already been developed in our laboratory, which would precisely control all flow conditions and make the system more user-friendly37. Overall, we envision that this device can become a low-cost, rapid, and multi-functional tool for whole blood processing in resource-limited environments or point-of-care settings.

Methods and Materials

Device fabrication

The microfluidic device was made of PDMS and fabricated using a standard soft lithography process. Briefly, PDMS prepolymer (Sylgard-184, Dow Corning) composed of precursor A, precursor B, and silicon oil at a ratio of 10:1:0.3 was poured onto a silicon mould with channel structures fabricated by the photolithography process. After heating in an oven at 60 °C for 4 hours, the fully cured PDMS structure was peeled off the mould. The inlet and outlet of the microchannel were then punched with 0.5-mm and 1-mm biopsy punches, respectively, followed by bonding to a glass slide using oxygen plasma (Plasma Cleaner PDC-001, Harrick Plasma) at 45 W for 60 s.

After bonding, the first six side channels were packed with 10-μm polystyrene beads (18337-2, Polysciences Inc., PA) from the outlet using a pneumatic pump (SH-P100, Shishin, Taiwan). To enable smooth and uniform bead packing, the bead mixture was first diluted with deionised (DI) water to 1.5 × 106 beads/mL and loaded into channels at two injection speeds (52 and 520 μL/min). The first injection allows gradual bead accumulation at the necked structure. The second injection is used to further squeeze the packed beads and increase their packing density. After the bead packing process, the device was placed into the oven at 60 °C for another 8 hours to remove all residual solvents. Before usage, the device was immersed in DI water with 3% Pluronic solution for 15 minutes to prevent the formation of any air bubbles and non-specific adhesion of blood cells.

Sample preparation and blood collection

In the simulation experiment using fluorescent beads, we used 2-μm red fluorescent beads (19508-2, Fluoresbrite® Polychromatic Red Microspheres, Polysciences Inc., PA) and 10-μm blue fluorescent beads (F8829, FluoSpheres™ Polystyrene Microspheres, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA). The clinical samples of whole blood were collected using a blood collection tube coated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (BD Vacutainer® spray-coated with K2EDTA, BD, NJ). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (201505009DINC), and all subjects were given written informed consent. All clinical experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The experiments were finished within 24 hours after sample collection. To visualise and count trapped WBCs in the device, the whole blood sample was stained by the cell viability assay dye Calcein AM. Calcein AM was diluted with diethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and mixed with the whole blood to a final concentration of 10 μM. The whole blood sample was then incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C for the following experiments.

For the blood type test, we injected 20 μL of anti-A, anti-B, and anti-D antibody solution (TECO Diagnostics, CA) into three 5-mm-diameter PDMS chambers. For A-type blood, antigen-A on the RBC surfaces interacts with the anti-A antibody, resulting in RBC agglutination. Similarly, agglutination in anti-B-treated solution represents B-type blood. Agglutination in both anti-A and anti-B treated solution indicates AB-type blood. However, if no agglutination occurs at all, the blood is type O. For the Rh blood group system, blood type is identified by the anti-D antibody.

Whole blood processing protocol using the microfluidic device

A 6 μL amount of whole blood sample and 60 μL of PBS solution were injected into the microfluidic device using two syringe pumps (Fusion 200, Chemyx Inc., TX) via the whole blood inlet and buffer inlet, respectively. The flow rates of whole blood and PBS were first set at 0.3 and 1 μL/min, respectively. In the first 3 minutes, a stable boundary layer between the whole blood and PBS was formed, and the flow pattern in the main channel became stable. The flow rate of PBS was then gradually increased to 3 μL/min to reduce the width of the whole blood flow. To collect plasma and RBCs, a pipette tip was inserted in the outlets of both side channels. Once the whole assay process was finished, the pipette tips can be directly unplugged for different tests. The WBC trapping process was recorded by a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (DP-80, Olympus) under an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, Olympus, Japan).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Taiwan University New Faculty Research Grant and the Ministry of Science and Technology under grant “MOST 105–2221-E-002–015”. We also acknowledge Nano-Electro-Mechanical Systems (NEMS) Research Centre, National Taiwan University for photolithography support.

Author Contributions

W.-Y.S. proposed the method and designed the device; D.-H.K., C.-C.W., W.-Y.S. and N.-T.H. conceived and designed the experiments; C.-C.W. and W.-Y.S. performed the experiments; D.-H.K., C.-C.W. and W.-Y.S. analysed the data; D.-H.K. interpreted results and wrote the manuscript; and N.-T.H. edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33738-8.

References

- 1.Christensen RD, Henry E, Jopling J, Wiedmeier SE. The CBC: Reference Ranges for Neonates. Seminars in Perinatology. 2009;33:3–11. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spell DW, Jones DV, Harper WF, David Bessman J. The value of a complete blood count in predicting cancer of the colon. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2004;28:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mach AJ, Adeyiga OB, Di Carlo D. Microfluidic sample preparation for diagnostic cytopathology. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:1011–1026. doi: 10.1039/c2lc41104k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou HW, et al. Microfluidic Devices for Blood Fractionation. Micromachines. 2011;2:319. doi: 10.3390/mi2030319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kersaudy-Kerhoas M, Sollier E. Micro-scale blood plasma separation: from acoustophoresis to egg-beaters. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:3323–3346. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50432h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhagat AAS, et al. Microfluidics for cell separation. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 2010;48:999–1014. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson J, Evander M, Hammarström B, Laurell T. Review of cell and particle trapping in microfluidic systems. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2009;649:141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, et al. High-throughput acoustic separation of platelets from whole blood. Lab on a Chip. 2016;16:3466–3472. doi: 10.1039/C6LC00682E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antfolk M, Magnusson C, Augustsson P, Lilja H, Laurell T. Acoustofluidic, Label-Free Separation and Simultaneous Concentration of Rare Tumor Cells from White Blood Cells. Analytical Chemistry. 2015;87:9322–9328. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dow P, Kotz K, Gruszka S, Holder J, Fiering J. Acoustic separation in plastic microfluidics for rapid detection of bacteria in blood using engineered bacteriophage. Lab on a Chip. 2018;18:923–932. doi: 10.1039/C7LC01180F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szydzik C, Khoshmanesh K, Mitchell A, Karnutsch C. Microfluidic platform for separation and extraction of plasma from whole blood using dielectrophoresis. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9:064120. doi: 10.1063/1.4938391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anas A, Ion S, Rama B, Ari-Nareg M. Interdigitated comb-like electrodes for continuous separation of malignant cells from blood using dielectrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2011;32:1327–1336. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthew SP, et al. Dielectrophoretic separation of platelets from diluted whole blood in microfluidic channels. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:1213–1218. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han K-H, Frazier AB. Paramagnetic capture mode magnetophoretic microseparator for high efficiency blood cell separations. Lab on a Chip. 2006;6:265–273. doi: 10.1039/B514539B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glynn MT, Kinahan DJ, Ducree J. Rapid, low-cost and instrument-free CD4 + cell counting for HIV diagnostics in resource-poor settings. Lab on a Chip. 2014;14:2844–2851. doi: 10.1039/C4LC00264D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karabacak NM, et al. Microfluidic, marker-free isolation of circulating tumor cells from blood samples. Nature Protocols. 2014;9:694–694. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo Hye-Kyoung, Kim Yong-Ho, Kim Hyun-Ok, Kim Yong-Jun. Hybrid cell sorters for on-chip cell separation by hydrodynamics and magnetophoresis. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering. 2010;20(9):095019. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/20/9/095019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi M, Madadi H, Casals-Terré J, Sellarès J. Hydrodynamic and direct-current insulator-based dielectrophoresis (H-DC-iDEP) microfluidic blood plasma separation. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2015;407:4733–4744. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields ICW, et al. Magnetic separation of acoustically focused cancer cells from blood for magnetographic templating and analysis. Lab on a Chip. 2016;16:3833–3844. doi: 10.1039/C6LC00719H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimov IK, et al. Stand-alone self-powered integrated microfluidic blood analysis system (SIMBAS) Lab on a Chip. 2011;11:845–850. doi: 10.1039/C0LC00403K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis JA, et al. Deterministic hydrodynamics: Taking blood apart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:14779–14784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605967103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripathi S, Kumar YVB, Agrawal A, Prabhakar A, Joshi SS. Microdevice for plasma separation from whole human blood using bio-physical and geometrical effects. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:26749. doi: 10.1038/srep26749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sollier E, Cubizolles M, Fouillet Y, Achard J-L. Fast and continuous plasma extraction from whole human blood based on expanding cell-free layer devices. Biomedical Microdevices. 2010;12:485–497. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung Y-C. Stochastic flow in capillary blood vessels. Microvascular Research. 1973;5:34–48. doi: 10.1016/S0026-2862(73)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen RT, Fung YC. Effect of velocity distribution on red cell distribution in capillary blood vessels. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1978;235:H251–H257. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.2.H251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid-Schönbein GW, Skalak R, Usami S, Chien S. Cell distribution in capillary networks. Microvascular Research. 1980;19:18–44. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Undar A, Zahn JD. A microfluidic device for continuous, real time blood plasma separation. Lab on a Chip. 2006;6:871–880. doi: 10.1039/B516401J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim M, Mo Jung S, Lee K-H, Jun Kang Y, Yang S. A Microfluidic Device for Continuous White Blood Cell Separation and Lysis From Whole Blood. Artificial Organs. 2010;34:996–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2010.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J-Y, Huang Y-T, Chou H-H, Wang C-P, Chen C-F. Rapid and inexpensive blood typing on thermoplastic chips. Lab on a Chip. 2015;15:4533–4541. doi: 10.1039/C5LC01172H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, et al. Microfluidic disk for the determination of human blood types. Microsystem Technologies. 2017;23:5645–5651. doi: 10.1007/s00542-017-3384-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji HM, et al. Silicon-based microfilters for whole blood cell separation. Biomedical Microdevices. 2008;10:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turgeon, M. L. Clinical Hematology: Theory and Procedures. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins), (2005).

- 33.Lewis, S. M., Bain, B. J., Bates, I. & Dacie, J. V. Dacie and Lewis Practical Haematology. (Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier), (2006).

- 34.Kuan D-H, et al. A microfluidic device integrating dual CMOS polysilicon nanowire sensors for on-chip whole blood processing and simultaneous detection of multiple analytes. Lab on a Chip. 2016;16:3105–3113. doi: 10.1039/C6LC00410E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harboe M. A Method for Determination of Hemoglobin in Plasma by Near-Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. 1959;11:66–70. doi: 10.3109/00365515909060410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh Erh-Chia, Fu Chi-Cheng, Hu Lucy, Thakur Rohan, Feng Jeffrey, Lee Luke P. Self-powered integrated microfluidic point-of-care low-cost enabling (SIMPLE) chip. Science Advances. 2017;3(3):e1501645. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Shu-Hong, Chang Yu-Shin, Juang Jyh-Ming Jimmy, Chang Kai-Wei, Tsai Mong-Hsun, Lu Tzu-Pin, Lai Liang-Chuan, Chuang Eric Y., Huang Nien-Tsu. An automated microfluidic DNA microarray platform for genetic variant detection in inherited arrhythmic diseases. The Analyst. 2018;143(6):1367–1377. doi: 10.1039/C7AN01648D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.