Abstract

The stability of a protein is vital for its biological function, and proper folding is partially driven by intermolecular interactions between protein and water. In many studies, H2O is replaced by D2O because H2O interferes with the protein signal. Even this small perturbation, however, affects protein stability. Studies in isotopic waters also might provide insight into the role of solvation and hydrogen bonding in protein folding. Here, we report a complete thermodynamic analysis of the reversible, two‐state, thermal unfolding of the metastable, 7‐kDa N‐terminal src‐homology 3 domain of the Drosophila signal transduction protein drk in H2O and D2O using one‐dimensional 19F NMR spectroscopy. The stabilizing effect of D2O compared with H2O is enthalpic and has a small to insignificant effect on the temperature of maximum stability, the entropy, and the heat capacity of unfolding. We also provide a concise summary of the literature about the effects of D2O on protein stability and integrate our results into this body of data.

Keywords: deuterium oxide, NMR spectroscopy, protein folding, protein stability, SH3 domain, solvent isotope effect, thermodynamics

Introduction

Water, arguably the most important molecule for life on Earth,1, 2 is essential for the stability, folding, and structure of proteins that drive biology. The hydrogen bonds between protein and water help shape the free energy landscape of folding, guiding a protein towards its stable, folded state. In many experimental techniques, however, the signal from H2O interferes with that from the protein, and D2O is used as the solvent. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), infrared spectroscopy, small angle X‐ray scattering, and small angle neutron scattering are techniques that often incorporate this substitution. Additionally, examining proteins in D2O, which is only a small perturbation of the system, can provide insight into the role of hydration and hydrogen‐bonding in protein folding.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Nonetheless, this solvent substitution can affect proteins,9 and it is important to be cognizant of these effects when conducting experiments in D2O. The aim of the present study is three‐fold: provide a complete thermodynamic analysis of globular protein folding in H2O and D2O, concisely summarize similar literature studies, and compare our results to those in the literature.

We chose the metastable, 7‐kDa N‐terminal src homology 3 domain of the Drosophila signal transduction protein drk (SH3) to probe solvent isotope effects on protein stability. Even under non‐denaturing conditions, a large population of SH3 is unfolded.10 SH3 has one tryptophan, which we labeled with a fluorine atom.11 This residue experiences different solvent exposure in the folded and unfolded states, resulting in two 19F resonances in slow exchange on the NMR timescale,10, 12 one for the folded state and one for the unfolded ensemble (Fig. 1). The presence of only two resonances is consistent with two‐state folding. The areas under the resonances can be integrated to obtain the relative populations of each state and thus a modified standard‐state free energy of unfolding:

| (1) |

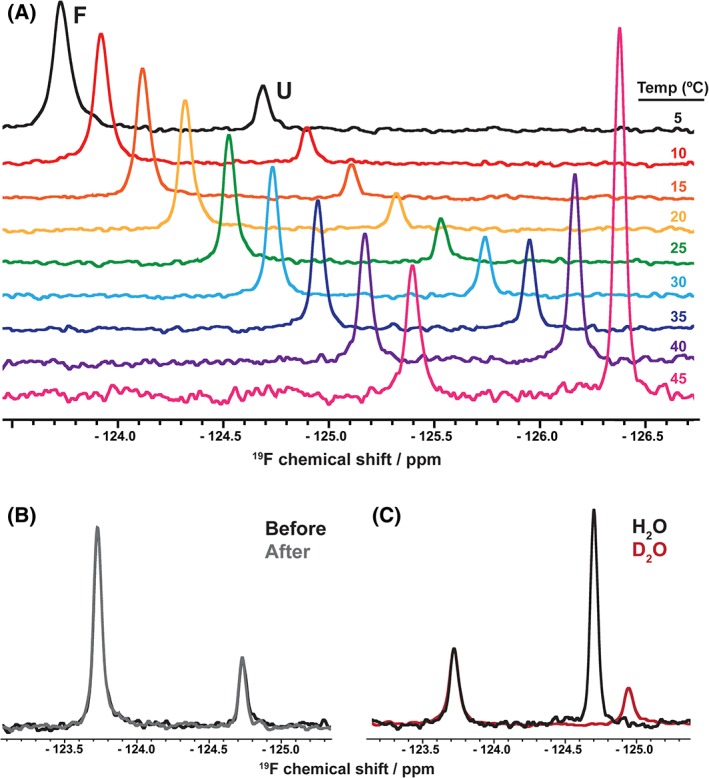

Figure 1.

Two‐state, temperature‐dependent, reversible SH3 folding in H2O and D2O monitored with 19F NMR. (A) One‐dimensional spectra in H2O at nine temperatures normalized to the intensity of the folded state peak at 5°C. Subsequent spectra are offset by −0.2 ppm to aid visualization. The downfield resonance is the folded state (F), and the upfield resonance is the unfolded ensemble (U). (B) Spectra at 25°C before (black) and after (gray) an experiment where the temperature ranged from 5°C to 45°C over approximately 180 min indicating the reversibility of denaturation. (C) Spectra in H2O (black) and D2O (red) at 45°C. The D2O spectrum is normalized to the chemical shift and intensity of the folded state resonance in H2O.

where R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature. The temperature dependence of is used to construct a protein stability curve (Fig. 2)13 which provides a complete thermodynamic picture of folding in H2O and D2O via the integrated Gibbs–Helmholtz equation:

| (2) |

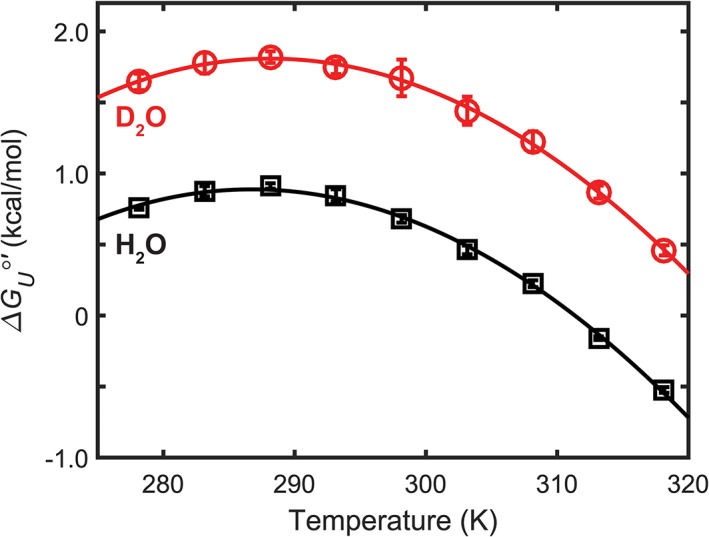

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of SH3 stability in H2O and D2O. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean from three independent trials.

where Tref is a reference temperature, and are the modified standard state enthalpy and entropy of unfolding, respectively, and is the modified standard state heat capacity of unfolding which is assumed to be temperature independent within the range studied.

Results and Discussion

Heat‐induced unfolding of SH3 in H2O and D2O

The metastability of this SH3 domain allows stability curves to be constructed and analyzed13, 14, 15 at reasonable temperatures (5°C–45°C). The stability curve in D2O is simply shifted above the curve in H2O (Fig. 2). This shift indicates that SH3 stability is greater in D2O at all temperatures and that the effects of D2O are mainly enthalpic.9, 14 , as well as , , and at any temperature can be calculated by fitting the data to Equation (2).

The thermodynamic parameters (Table 1) paint a picture of the solvent isotope effect. At 318 K, approximately half way between Tm in D2O and H2O, the heavy water stabilizes the protein by nearly 1 kcal/mol [Fig. 1(C)]. This increase is also visible by comparing the Tm (the melting temperature, where ). D2O increases this value by approximately 12 K, indicating an increased thermal stability. The higher stability in D2O is often rationalized in terms of the increased difficulty of cavity creation in D2O compared with H2O.9, 16, 17

Table 1.

Equilibrium thermodynamic parameters for SH3 in H2O and D2O

| Condition | (kcal/mol)a | (kcal/mol)b | (kcal/mol)b | (kcal/mol)c | (kcal/mol)c | (kcal/mol/K)b | Tm (K)b | Ts (K)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | −0.52 ±0.02 | 22 ±2 | 0.89 ±0.03 | 28 ±1 | 28 ±1 | 0.86 ±0.09 | 311 ±1 | 287 ±1 |

| D2O | 0.46 ±0.04 | 33 ±2 | 1.8 ±0.1 | 29 ±1 | 28 ±1 | 0.89 ±0.07 | 323 ±1 | 288 ±1 |

Uncertainties determined from standard error of the mean from triplicate experimental analysis.

Uncertainties determined from 95% confidence intervals of fit to the integrated Gibbs–Helmholtz equation.

The temperature half way between Tm in H2O and D2O. Values from Kirchhoff's equations and uncertainties by error propagation from the uncertainties in , Tref (Tm or Ts), and ( or )

Breaking into its enthalpic and entropic components shows only an effect on the enthalpy of unfolding. In both H2O and D2O, the enthalpy and entropy of unfolding are large and positive making it difficult to determine which one dominates at 318 K. Examining the enthalpy at the temperature of maximum stability, Ts, is more useful due to the small uncertainty in the value at this temperature. At Ts the entropy is zero,13 and therefore differences in enthalpy are identified. Additionally, Ts is nearly the same in H2O and D2O. The in H2O is 0.89 ±0.03 kcal/mol, whereas in D2O, it is twice as large (1.8 ±0.1 kcal/mol). The curvature is the same in both solvents. This is quantitatively demonstrated by a minimal change in . In summary, at all temperatures, the increased stability of SH3 in D2O is dominated by .

Origins of the D2O effect

The molecular origins of this enthalpic stabilization are difficult to pinpoint, especially since they cannot be directly measured. D2O stabilization of proteins is often attributed to an increase in hydrogen bond strength in heavy water,18, 19, 20, 21, 22 which is also consistent with the observation that D2O reduces protein flexibility.23, 24 Although a change in solvent hydrogen bond strength would be reflected in a change in enthalpy because there are numerous solvent–solvent, solvent–protein, and protein–protein hydrogen bonds formed during protein folding, there are multiple contributions to the enthalpy of unfolding.25 In addition to the enthalpy from hydrogen bond formation and breakage, solvation enthalpy also plays a significant role in protein folding.9 Protein unfolding involves solvation of groups that are buried in the folded state. The enthalpy of solvation for a particular protein is, therefore, based on its sequence, structure, and changes in the solvent accessible surface area upon unfolding. Solvation enthalpies are typically based on studies of small molecules, which are then used in combination to calculate a net enthalpy of protein solvation.9, 25 These solvation enthalpies are large in magnitude and opposite in sign for apolar versus polar groups, often resulting in small estimated net enthalpy changes of both signs for an entire protein. It is likely that the observed increase in the enthalpy of SH3 unfolding in D2O arises from a combination of solvation and hydrogen‐bond effects.

The heat capacity of unfolding, which is related to solvation changes upon unfolding, is often difficult to quantitatively interpret due to the relatively large uncertainty in its value (~10%, Table 1).9 Additionally, we assume that does not change with temperature, which is not necessarily true,13, 25, 26 but a good assumption over a small range, like the one used here.13, 27 For SH3, () is 0.0 ±0.1 kcal/mol/K, meaning that any change is too small to interpret, which suggests that is constant from 5 °C to 45 °C. This conclusion is consistent with other observations.9, 22, 28 As suggested in the previous paragraph, the change in the heat capacity of transfer of hydrophilic versus hydrophobic protein groups from light‐ to heavy‐water are often large and opposite in sign,9 resulting in a minimal and uncertain change in .

Literature studies find D2O is primarily stabilizing

The effects of D2O on protein stability have been of interest for decades (Table 2). The purpose of Table 2 is to highlight peer‐reviewed publications in which the stability of a protein is directly compared in H2O and D2O. The majority of studies reveal that D2O stabilizes proteins. The parameter most used to assess the influence of heavy water is its effect on the melting temperature, Tm. Although the degree to which D2O increases the Tm of a particular protein varies, our data is in accord with the literature19, 21, 22, 28, 30, 31, 32, 36, 37 in that the Tm of a protein increases upon changing H2O to D2O. In all studies, but one,32 that report along with Tm, an increased melting temperature is accompanied by an increase in the free energy of unfolding.22, 28, 35 In the case of phycocyanin,30 an increase in the activation free energy of denaturation is observed.

Table 2.

Effects of D2O on Protein Stability

| Protein | Method | Effect of D2O | Parameter(s) examined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovalbumin29 | Urea, polarimetry | Stabilizing | t 1/2 |

| Ribonuclease19, 21 | Heat, polarimetry | Stabilizing | T m |

| Phycocyanin30 | Heat, absorbance spectroscopy, fluorescence quenching | Stabilizing | T m , ΔH°′ ‡ , ΔS°′ ‡ , ΔG°′ ‡ |

| Staphylococcal nuclease31 | Heat, GdnSCN, GdnHCl, NMR, CD, fluorescence spectroscopy | Stabilizing | T m |

| Bovine ribonuclease A32 | DSC | Small | ΔH°′, ΔG°′, T m |

| Hen egg lysozyme32 | DSC | Destabilizing | ΔH°′, ΔG°′, T m |

| Cytochrome c 32 | DSC | Destabilizing | ΔH°′, ΔG°′, T m |

| Malate dehydrogenase33 | Enzyme assay | Stabilizing | Residual enzyme activity |

| Staphylococcal nuclease34 | Urea, CD, FTIR | Stabilizing | m‐Value, ΔG°’ |

| Domain 1 of rat CD235 | GdnHCl, stopped‐flow fluorescence spectroscopy | Stabilizing | ΔG°′, ΔG°′ ‡, k I‐F , k F‐I , m‐values |

| NTL928 | Heat, urea, GdnHCl, far‐UV CD | Stabilizing | T m , ΔG°′, ΔH°′, ΔS°′, m‐values, ΔC p °′ |

| β‐lactoglobulin36 | DSC, DLS | Stabilizing | T m , ΔH°′ |

| Ribonuclease A37 | Heat, urea, CD, fluorescence spectroscopy, HDX NMR | Stabilizing | T m , ΔH°, ΔC p °′ |

| Ribonuclease T137 | Heat, urea, CD, fluorescence spectroscopy, HDX NMR | Stabilizing | T m , ΔH°, ΔC p °’ |

| Polyproline type II helix38 | CD | Stabilizing | Polyproline II content |

| Hen egg lysozyme22 | DSC | Stabilizing | T m , ΔG°′, ΔH°′, ΔS°′, ΔC p °’ |

| Bovine serum albumin22 | DSC | Stabilizing | T m , ΔG°′, ΔH°′, ΔS°′, ΔC p °’ |

| Bovine serum albumin39 | Heat, far‐UV CD | Stabilizing | Molar ellipticity |

Abbreviations: t 1/2, half‐time of denaturation reaction; GdnSCN, guanidine thiocyanate; GdnHCl, guanidine hydrochloride; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy; CD, circular dichroism spectropolarimetry; k I‐F, rate of intermediate to folded state reaction; k F‐I, rate of folded state to intermediate reaction; NTL9, N‐terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9; UV, ultraviolet; ΔC p °′, change in heat capacity; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; DLS, dynamic light scattering; HDX, hydrogen–deuterium exchange.

Additional equilibrium thermodynamic parameters describing protein stability became more commonplace with the advent of highly accurate calorimeters. Differential scanning calorimetry is particularly useful because the melting temperature, enthalpy, and heat capacity of unfolding can be measured.40, 41 All but one study32 reports results similar to ours: D2O increases the enthalpy of unfolding.22, 30, 36, 40 One report28 shows minimal changes to and increases in both Tm and . Attempts have been made to describe the molecular basis of this change in enthalpy, often attributed to increased hydrogen‐bond strength. As described here, however, there are likely multiple contributions making it difficult to ascribe its effects to hydrogen bonding or solvation alone. Some investigators also report the entropy of unfolding28, 30; but like enthalpy, it contains multiple contributions.25 In summary, our results correspond to almost all published observations: D2O increases the stability (),22, 28, 30, 34, 35, 37 the melting temperature (Tm),19, 21, 22, 28, 30, 31, 32, 36, 37 and the enthalpy of protein unfolding ().22, 30, 36, 37

D2O affects many biological processes

Although we focus on protein stability, the effects of D2O on many biological processes have been investigated with the potential for widespread impact on the fundamental roles of water in biology and therapeutics. D2O affects protein–carbohydrate, protein–peptide, and protein–nucleic acid interactions,42 with effects on the enthalpy of binding. In addition to binding, D2O enhances protein oligomerization and aggregation,36, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 by what has been suggested to be the promotion of hydrophobic interactions. Given the influence of heavy water on biomolecular reactions, D2O is also expected to affect whole organisms. Research in this field began as soon as the deuterium isotope was discovered53 and isolated54 in the 1930s. High concentrations of D2O have deleterious effects on organismal growth and survival from microorganisms like Escherichia coli 55, 56 and yeast57, 58 to algaes,59, 60 plants,58, 61, 62 and animals such as mice58, 60, 63 and dogs55. However, the natural abundance of deuterium in nature is approximately 156 ppm.64, 65 More recent studies show that low concentrations may be necessary and even beneficial,66, 67 with interesting recent hypotheses on the use of heavy isotopes for increasing human longevity.68 Finally, there is some interest in the use of D2O as an excipient52, 69 because of the observation that D2O can stabilize vaccines.70

Understanding the effects of isotopic waters is key to understanding biology, including protein folding. We focused on the equilibrium thermodynamics of D2O on protein stability, because stably folded proteins are often a pre‐requisite to proper biological function. We anticipate that our results and those of others compiled here will be of use for understanding the effects of the molecule that unites all of life on Earth.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

5‐Fluorotryptophan‐labeled SH3 was expressed and purified as described.71, 72

NMR

NMR samples were prepared as described.14, 15, 71 Briefly, 1 mg of fluorine‐labeled, SH3 was resuspended in NMR buffer (50 mM HEPES, bis–tris propane, sodium acetate/acetic acid, pH 7.2) made using H2O or 99.9% D2O. pH readings are direct measurements and uncorrected for the D2O isotope effect.73 For samples prepared in H2O, a coaxial‐insert containing D2O was used to lock the spectrometer. 4,4‐Dimethyl‐4‐silapentane‐1‐sulfonic acid (DSS, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Cambridge, UK) was used as a chemical shift reference. One‐dimensional 19F spectra were acquired at 5°C increments between 5°C and 45°C on a Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer operating at a 19F Larmor frequency of 470 MHz equipped with a Bruker QCI cryoprobe.

Data processing and analysis

Data were processed as described using Topspin 3.2.14, 15, 71 The parameters shown in Table 1 were calculated using Kirchhoff's equations and the integrated Gibbs‐Helmholtz equation as described14 using MATLAB R2016a.

Note added in proof. After our manuscript was accepted, we learned about work that more completely explains the stabilizing effect of D2O. [Pica A, Graziano G (2018) Effect of heavy water on the conformational stability of globular proteins. Biopolymers, 2017].

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pielak lab for helpful discussions, Greg Young for spectrometer maintenance, and Elizabeth Pielak for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1. Chaplin MF (2001) Water: its importance to life. Biochem Mol Bio Edu 29:54–59. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaplin M (2006) Do we underestimate the importance of water in cell biology? Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 7:861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujita Y, Noda Y (1981) Effect of hydration on the thermal stability of protein as measured by differential scanning calorimetry. Chymotrypsinogen A. Int J Pept Protein Res 18:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Privalov PL, Makhatadze GI (1993) Contribution of hydration to protein folding thermodynamics. II. The entropy and Gibbs energy of hydration. J Mol Biol 232:660–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL (1993) Contribution of hydration to protein folding thermodynamics. I. The enthalpy of hydration. J Mol Biol 232:639–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rose GD, Wolfenden R (1993) Hydrogen bonding, hydrophobicity, packing, and protein folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 22:381–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez MM, Makhatadze GI (1998) Solvent isotope effect on thermodynamics of hydration. Biophys Chem 74:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krantz BA, Moran LB, Kentsis A, Sosnick TR (2000) D/H amide kinetic isotope effects reveal when hydrogen bonds form during protein folding. Nat Struct Biol 7:62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oas TG, Toone EJ (1997) Thermodynamic solvent isotope effects and molecular hydrophobicity. Adv Biophys Chem 6:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang O, Forman‐Kay JD (1995) Structural characterization of folded and unfolded states of an SH3 domain in equilibrium in aqueous buffer. Biochemistry 34:6784–6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crowley PB, Kyne C, Monteith WB (2012) Simple and inexpensive incorporation of 19F tryptophan for protein NMR spectroscopy. Chem Commun 48:10681–10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evanics F, Bezsonova I, Marsh J, Kitevski JL, Forman‐Kay JD, Prosser RS (2006) Tryptophan solvent exposure in folded and unfolded states of an SH3 domain by 19F and 1H NMR. Biochemistry 45:14120–14128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Becktel WJ, Schellman JA (1987) Protein stability curves. Biopolymers 26:1859–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Senske M, Smith AE, Pielak GJ (2016) Protein stability in reverse micelles. Angew Chem Int Ed 55:3586–3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith AE, Zhou LZ, Gorensek AH, Senske M, Pielak GJ (2016) In‐cell thermodynamics and a new role for protein surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:1725–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benjamin L, Benson GC (1963) A deuterium isotope effect on excess enthalpy of methanol‐water solutions. J Phys Chem 67:858–861. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scheiner S, Cuma M (1996) Relative stability of hydrogen and deuterium bonds. J Am Chem Soc 118:1511–1521. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kresheck GC, Schneider H, Scheraga HA (1965) The effect of D2O on the thermal stability of proteins. Thermodynamic parameters for the transfer of model compounds from H2O to D2O. J Phys Chem 69:3132–3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheraga HA (1960) Helix‐random coil transformations in deuterated macromolecules. Ann NY Acad Sci 84:608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nemethy G, Steinberg IZ, Scheraga HA (1963) Influence of water structure and of hydrophobic interactions on the strength of side‐chain hydrogen bonds in proteins. Biopolymers 1:43–69. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hermans J, Scheraga HA (1959) The thermally induced configurational change of ribonuclease in H2O and D2O. Biochim Biophys Acta 36:534–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Efimova YM, Haemers S, Wierczinski B, Norde W, van Well AA (2007) Stability of globular proteins in H2O and D2O. Biopolymers 85:264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guzzi R, Arcangeli C, Bizzarri AR (1999) A molecular dynamics simulation study of the solvent isotope effect on copper plastocyanin. Biophys Chem 82:9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cioni P, Strambini GB (2002) Effect of heavy water on protein flexibility. Biophys J 82:3246–3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL (1995) Energetics of protein structure. Adv Prot Chem 47:307–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bakk A, Hoye JS, Hansen A (2002) Apolar and polar solvation thermodynamics related to the protein unfolding process. Biophys J 82:713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Senske M, Tork L, Born B, Havenith M, Herrmann C, Ebbinghaus S (2014) Protein stabilization by macromolecular crowding through enthalpy rather than entropy. J Am Chem Soc 136:9036–9041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuhlman B, Raleigh DP (1998) Global analysis of the thermal and chemical denaturation of the N‐terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9 in H2O and D2O. Determination of the thermodynamic parameters, ΔH°, ΔS°, and ΔC p °, and evaluation of solvent isotope effects. Protein Sci 7:2405–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maybury RH, Katz JJ (1956) Protein denaturation in heavy water. Nature 177:629–630. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hattori A, Crespi HL, Katz JJ (1965) Effect of side‐chain deuteration on protein stability. Biochemistry 4:1213–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Antonino LC, Kautz RA, Nakano T, Fox RO, Fink AL (1991) Cold denaturation and 2H2O stabilization of a staphylococcal nuclease mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:7715–7718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Makhatadze GI, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM (1995) Solvent isotope effect and protein stability. Nat Struct Biol 2:852–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Madern D, Zaccai G (1997) Stabilisation of halophilic malate dehydrogenase from Haloarcula marismortui by divalent cations – effects of temperature, water isotope, cofactor and pH. Eur J Biochem 249:607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. From NB, Bowler BE (1998) Urea denaturation of staphylococcal nuclease monitored by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37:1623–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parker MJ, Clarke AR (1997) Amide backbone and water‐related H/D isotope effects on the dynamics of a protein folding reaction. Biochemistry 36:5786–5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verheul M, Roefs SP, de Kruif KG (1998) Aggregation of β‐lactoglobulin and influence of D2O. FEBS Lett 421:273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huyghues‐Despointes BMP, Scholtz JM, Pace CN (1999) Protein conformational stabilities can be determined from hydrogen exchange rates. Nat Struct Biol 6:910–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chellgren BW, Creamer TP (2004) Effects of H2O and D2O on polyproline II helical structure. J Am Chem Soc 126:14734–14735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fu L, Villette S, Petoud S, Fernandez‐Alonso F, Saboungi ML (2011) H/D isotope effects in protein thermal denaturation: the case of bovine serum albumin. J Phys Chem B 115:1881–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jackson WM, Brandts JF (1970) Thermodynamics of protein denaturation. Calorimetric study of the reversible denaturation of chymotrypsinogen and conclusions regarding the accuracy of the two‐state approximation. Biochemistry 9:2294–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ibarra‐Molero B, Naganathan AN, Sanchez‐Ruiz JM, Muñoz V. Chapter twelve – Modern analysis of protein folding by differential scanning calorimetry In: Feig AL, Ed. (2016) Methods in Enzymology. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp. 281–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chervenak MC, Toone EJ (1994) A direct measure of the contribution of solvent reorganization to the enthalpy of binding. J Am Chem Soc 116:10533–10539. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Woodfin BM, Henderson RF, Henderson TR (1970) Effects of D2O on the association–dissociation equilibrium in subunit proteins. J Biol Chem 245:3733–3737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baghurst PA, Nichol LW, Sawyer WH (1972) The effect of D2O on the association of β‐lactoglobulin a. J Biol Chem 247:3199–3204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uratani Y (1974) Polymerization of Salmonella flagellin in water and deuterium oxide media. J Biochem 75:1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harmony JAK, Himes RH, Schowen RL (1975) Monovalent cation‐induced association of formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase subunits – solvent isotope‐effect. Biochemistry 14:5379–5386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee JJ, Berns DS (1968) Protein aggregation. The effect of deuterium oxide on large protein aggregates of C‐phycocyanin. Biochem J 110:465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bonneté F, Madern D, Zaccai G (1994) Stability against denaturation mechanisms in halophilic malate‐dehydrogenase "adapt" to solvent conditions. J Mol Biol 244:436–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Omori H, Kuroda M, Naora H, Takeda H, Nio Y, Otani H, Tamura K (1997) Deuterium oxide (heavy water) accelerates actin assembly in vitro and changes microfilament distribution in cultured cells. Eur J Cell Biol 74:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chakrabarti G, Kim S, Gupta ML, Barton JS, Himes RH (1999) Stabilization of tubulin by deuterium oxide. Biochemistry 38:3067–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Panda D, Chakrabarti G, Hudson J, Pigg K, Miller HP, Wilson L, Himes RH (2000) Suppression of microtubule dynamic instability and treadmilling by deuterium oxide. Biochemistry 39:5075–5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Reslan M, Kayser V (2016) The effect of deuterium oxide on the conformational stability and aggregation of bovine serum albumin. Pharm Dev Tech 19:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Urey HC, Brickwedde FG, Murphy GM (1932) Relative abundance of H1 and H2 in natural hydrogen. Phys Rev 40:464–465. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lewis GN (1933) The isotope of hydrogen. J Am Chem Soc 55:1297–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Katz JJ (1960) Chemical and biological studies with deuterium. Am Sci 48:544–580. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Katz JJ (1960) The biology of heavy water. Sci Am 203:106–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Richards OW (1934) The effect of deuterium on the growth of yeast. J Bacteriol 28:289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lewis GN (1934) The biology of heavy water. Science 79:151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Crespi HL, Archer SM, Katz JJ (1959) Culture of algae and other micro‐organisms in deuterium oxide. Nature 184:729–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Katz JJ, Crespi HL, Czajka DM, Finkel AJ (1962) Course of deuteriation and some physiological effects of deuterium in mice. Am J Physiol 203:907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bhatia CR, Smith HH (1968) Adaptation and growth response of Arabidopsis thaliana to deuterium. Planta 80:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Labouriau LG (1980) Effects of deuterium oxide on the lower temperature limit of seed germination. J Therm Biol 5:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomson JF (1960) Physiological effects of D2O in mammals. Ann NY Acad Sci 84:736–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gat JR, Gonfiantini R. Stable Isotope hydrology: deuterium and oxygen‐18 in the water cycle. IAEA Technical Report Series #210, Vienna, 337.

- 65. Rumble JR. Physical constants of organic compounds. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, FL.

- 66. Somlyai G, Jancso G, Jakli G, Vass K, Barna B, Lakics V, Gaal T (1993) Naturally‐occurring deuterium is essential for the normal growth‐rate of cells. FEBS Lett 317:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hammel SC, East K, Shaka AJ, Rose MR, Shahrestani P (2013) Brief early‐life non‐specific incorporation of deuterium extends mean life span in Drosophila melanogaster without affecting fecundity. Rejuv Res 16:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Xiyan L, P. SM (2016) Can heavy isotopes increase lifespan? Studies of relative abundance in various organisms reveal chemical perspectives on aging. BioEssays 38:1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jena S, Horn J, Suryanarayanan R, Friess W, Aksan A (2017) Effects of excipient interactions on the state of the freeze‐concentrate and protein stability. Pharm Res 34:462–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sen A, Balamurugan V, Rajak KK, Chakravarti S, Bhanuprakash V, Singh RK (2009) Role of heavy water in biological sciences with an emphasis on thermostabilization of vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 8:1587–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stadmiller SS, Gorensek‐Benitez AH, Guseman AJ, Pielak GJ (2017) Osmotic shock induced protein destabilization in living cells and its reversal by glycine betaine. J Mol Biol 429:1155–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gorensek‐Benitez AH, Smith AE, Stadmiller SS, Perez Goncalves GM, Pielak GJ (2017) Cosolutes, crowding, and protein folding kinetics. J Phys Chem B 121:6527–6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Glasoe PK, Long FA (1960) Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J Phys Chem 64:188–190. [Google Scholar]