Abstract

Anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitors enhance the antitumour activity of the immune system and have produced durable tumour responses in several solid tumours including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, PD-1 inhibitors can lead to immune-related adverse events, including pneumonitis, which is typically mild, but can be severe and potentially fatal. Pneumonitis often resolves with steroids, but some cases are steroid refractory, leading to a relapsing and remitting course in milder cases or the need for salvage therapies in more severe cases. Here, we present two patients with NSCLC who developed severe pneumonitis following therapy with nivolumab and pembrolizumab. While one patient improved with steroids and infliximab, the other patient failed to respond to steroids and subsequently died. These cases demonstrate the highly variable presentation and therapeutic responses seen in patients with pneumonitis following anti-PD-1 therapy and illustrate that severe cases can often present refractory to steroid therapy.

Keywords: immunological products and vaccines, immunology, lung cancer (oncology), unwanted effects / adverse reactions, cancer intervention

Background

The programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway plays a critical role in promoting tumour evasion from the immune system. PD-1 is a coinhibitor receptor expressed by T-cells, and functions as a negative regulator of T-cell activity within the tumour microenvironment. PD-1 has two known ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are normally expressed in the normal lung and promote peripheral tolerance. However, tumour cells often express PD-L1, which promotes immune evasion by inhibiting normal T cell function. This observation led to the development of PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor antibodies, which effectively restore T-cell effector function and help augment the host antitumour response by blocking the binding of PD-L1 and PD-L2 to PD-1 receptors.

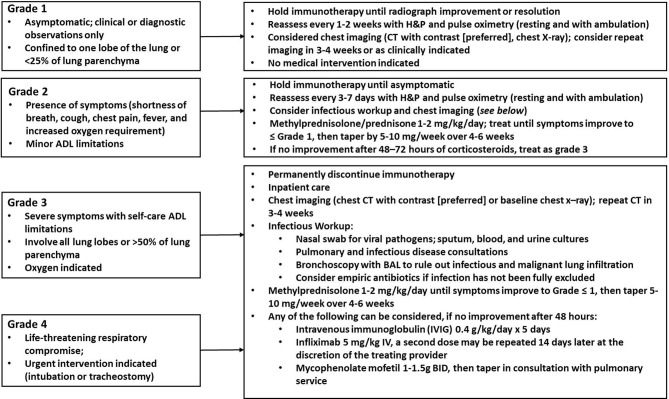

Nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda), which are monoclonal IgG4 antibodies designed to block the PD-1 receptor, have demonstrated substantial activity in patients with non-small cell carcinoma lung cancer, melanoma and renal cell cancer.1–4 PD-1 inhibitors typically have a milder and more manageable side effect profile, but are associated with unique side effects termed immune-related adverse events.5 This includes dermatological toxicity (maculopapular erythematous rash, pruritus and oral mucositis), mucosal toxicity (diarrhoea, colitis), hepatotoxicity, endocrinopathies and pneumonitis.6 Pneumonitis is uncommon, but can be potentially life threatening.1 7 The median time to onset is 2.8 months, but ranges from 9 days to 19.2 months.7 Pneumonitis is thought to result from disrupting normal mechanisms of immune tolerance, resulting in increased activation of immune cells against the normal lung parenchyma. Unlike other drugs (ie, bleomycin) that produce specific radiological findings, pneumonitis induced by PD-1 inhibitors does not result in pathognomonic radiographic or pathological features.7 It is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring consideration of alternate diagnoses including infection, malignant lung infiltration and radiation-induced pneumonitis. Treatment is dependent on the severity (figure 1).8–10

Figure 1.

Grading and treatment of pneumonitis. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; H&P, History and Physical Exam.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 66-year-old man with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) presented with progressively worsening dyspnoea. Fourteen months prior, he was diagnosed with stage IIIA (T3N2M0) adenocarcinoma of the right upper lobe (RUL) of the lung, and was treated with concurrent chemotherapy (cisplatin 50 mg/m2 and etoposide 50 mg/m2) and radiation (50.4 Gy in 28 fractions), followed by a right lobectomy. Several months later, clinical and radiographic progression was evident, with multiple new sites of metastatic disease. Further genetic testing revealed a microsatellite stable tumour with a low tumour mutation burden, but a PD-L1 level of 70%, and he was consequently started on 240 mg nivolumab every 2 weeks.

On admission (day 126 of nivolumab therapy), the patient reported a 7-day history of increasing shortness of breath, severe fatigue and nausea. He denied any fevers, chills, cough, sputum production, haemoptysis or exposure to sick contacts. He had no unilateral calf tenderness, erythema or swelling. The patient was afebrile on admission. His oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 91% on room air, and he was started on supplemental oxygen. Course breath sounds with scattered crackles were auscultated, bilaterally. The remainder of his examination was unremarkable.

Case 2

A 63-year-old woman with a 76 pack-year smoking history and stage IIIB NSCLC presented with progressively worsening dyspnoea. Three months prior, she was diagnosed with stage IIIB (T2aN3M0) moderately differentiated squamous cell cancer of the left upper lobe (LUL) of the lung. Genetic testing showed a PD-L1 level of 60% and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) testing was negative. She was ineligible for concurrent chemoradiation with platinum-based chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for stage IIIB disease, due to her poor performance status. There are several ongoing trials testing concurrent immunotherapy with radiation, but the patient was ineligible for several trials since she had not received prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Preclinical and early clinical data have suggested a synergistic effect between checkpoint inhibitors with radiotherapy, and so the patient was treated off-label with 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks and concurrent radiotherapy (66 Gy in 32 fractions).

On admission (day 48 of pembrolizumab), she reported a 4-day history of progressively worsening dyspnoea, a non-productive cough, subjective fevers and episodes of diarrhoea. She denied any haemoptysis, wheezing or exposure to sick contacts. She denied any unilateral calf tenderness, erythema or swelling. Her SpO2 was initially in the 70s, but improved to 85% on high-flow oxygen. On examination, the patient was afebrile. Respirations were laboured, and bilateral wheezes and crackles were auscultated. The remainder of her examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Case 1

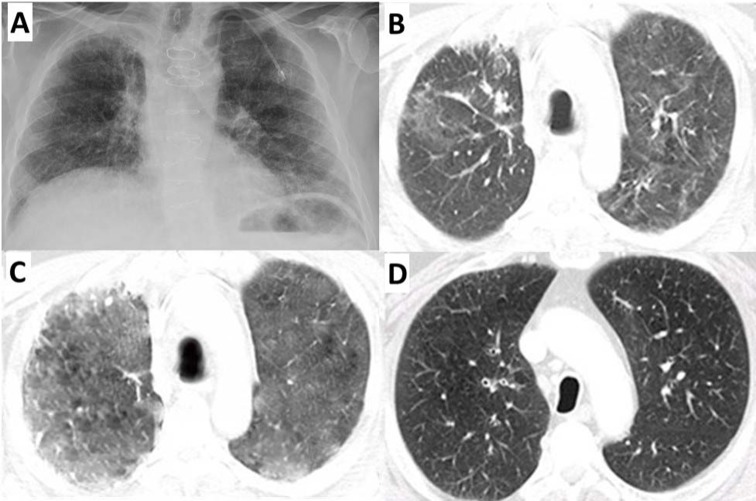

Laboratories showed a normal white cell count and plasma procalcitonin level. Sputum and blood cultures were negative. A CXR showed bilateral interstitial opacities consistent with either pneumonia or pneumonitis (figure 2A). Increased bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities were evidence throughout the lungs on chest CT scan (figure 2B). An arterial blood gas (ABG) demonstrated a arterial oxygen tension (PaO2)/fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio of 195 mm Hg. Bronchoscopy showed copious, clear, thin, secretions throughout the tracheobronchial tree. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid contained 5.2×105 cells/mL with 79% macrophages, 4% lymphocytes and 17% PMNs. Microbial testing results were negative (including staining and culture for bacterial, fungal and mycobacteria). BAL testing returned negative for Legionella, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Aspergillus and Pneumocystis jiroveci. Cytological analysis for malignant cells was negative. The patient was diagnosed with grade 3 anti-PD-1-induced pneumonitis. He was stared on 2 mg/kg intravenous methylprednisolone for 3 days, followed by conversion to 1 mg/kg/day PO prednisone. After 5 days of steroids, his dyspnoea had resolved and his SpO2 had improved to 95% on room air. He was discharged on 1 mg/kg/day PO prednisone and Bactrim for PCP prophylaxis. One week later, he was readmitted to the hospital for worsening dyspnoea and a SpO2 of 82% on room air. Infection and pulmonary embolism were ruled out. He had course dry crackles and a chest CT scan showed increasing ground-glass densities throughout both lungs (figure 2C). He received one dose of 5 mg/kg intravenous infliximab and was continued on 1 mg/kg/day PO prednisone. After 5 days, his dyspnoea had subsided and his SpO2 was above 95% on 2 L of oxygen, and he was discharged on 1 mg/kg/day prednisone. One month later, he was readmitted to the hospital for left-sided chest pain and severe fatigue. Lung auscultation showed clear breath sounds and a chest CT showed improved lung aeration with markedly decreased ground-glass attenuation (figure 2D), suggesting both clinical and radiographic evidence of resolving pneumonitis. However, CT scans also showed disease progression. About 1 week later, he elected to enrol in outpatient hospice.

Figure 2.

(A) Chest X-ray at the time of his first hospital admission. CT with contrast at the time of his (B) first, (C) second and (D) third hospital admission. Bilateral interstitial and airspace opacities consistent with pneumonitis were evident during the first two hospital admissions (B and C), but largely resolved during the third hospital admission (D).

Case 2

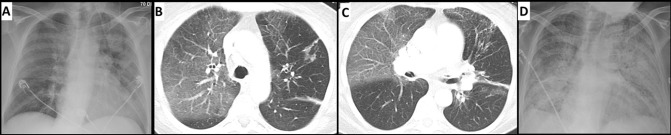

An ABG was consistent with acute hypoxic respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 of 131 mm Hg), with elevated lactate (2.25 mM). Laboratories showed no leucocytosis. A chest X-ray demonstrated predominantly upper lobe opacities (figure 3A). A chest CT displayed no evidence of pulmonary embolism, but showed a 3 cm nodule in the LUL and multiple satellite nodules. There were new multifocal ground-glass opacities and septal thickening in both lungs, most prominent in the RUL, consistent with pneumonitis (figure 3B,C). The patient was started on a 5-day course of azithromycin, vancomycin and cefepime. She was placed on CPAP/BiPAP, but she continued to worsen. Over the next week, her respiratory status declined, and the patient was intubated. A viral respiratory pathogen panel, Legionella urine antigen, Pneumococcal urine antigen and sputum cultures were negative. Bronchoscopy demonstrated mucoid secretions, bilaterally. BAL was performed in the RUL and LUL. BAL fluid contained 3.6×105 cells/mL with 91% macrophages, 3% lymphocytes and 6% PMNs. Fluid analysis was negative for H. capsulatum, B. dermatitidis, Aspergillus and P. jiroveci. Bacterial, acid-fast and fungal cultures were also negative. Legionella cultures were negative, but PCR analysis from the BAL of the LUL returned positive for Legionella. The patient was started on levofloxacin for 14 days. There was concern for grade 4 anti-PD-1-induced pneumonitis, and she was started on 1 mg/kg intravenous methylprednisolone, two times a day. Despite completing 2 weeks of steroids and levofloxacin, the patient showed no clinical improvement. Chest X-ray showed worsening interstitial pneumonitis throughout the lungs (figure 3D). Additional immunosuppression was offered (infliximab, cyclophosphamide), but the patient declined further treatment. Her oxygen status worsened over subsequent days and the patient expired.

Figure 3.

(A) Chest X-ray at the time of hospital admission showing upper lobe predominant airspace disease, consistent with pneumonitis. (B, C) CT with contrast at the time of hospital admission showing axial slices. Ground-glass attenuation and interlobular septal thickening in both lungs, most prominent in the right lobe. (D) Chest X-ray on day 28 of admission showing worsening acute interstitial pneumonitis throughout the lungs.

Differential diagnosis

Infection.

Malignancy progression.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Interstitial lung disease.

Drug-induced pneumonitis.

Radiation-induced lung injury.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient 1 enrolled in outpatient hospice and died 1 month following his last hospitalisation. Unfortunately, patient 2 died during her initial hospitalisation.

Discussion

Pneumonitis is a relatively rare, but potentially life-threatening complication of treatment with PD-1 inhibitors. A diagnosis of pneumonitis requires ruling out infection, cancer progression and radiation-induced pneumonitis. Neither patient showed signs of tumour progression or signs of infection at the time of admission. Patient 2 later tested positive for Legionella DNA by PCR, but the remaining BAL cultures and PCR testing for Legionella was negative, suggesting a possible false-positive. False-positive Legionella results are rare, but can occur.11 In addition, patient 2 was treated for 5 days with azithromycin, followed by 14 days with levofloxacin, which should have provided more than adequate treatment for Legionella. Yet, her breathing and imaging findings continued to worsen, strongly supporting the diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced pneumonitis. Radiation-induced pneumonitis was also considered. The diagnosis is based on a combination of typical symptoms, timing and dose of radiation, compatible imaging findings that conform to the prior radiation fields, and exclusion of alternative diagnoses. Each patient met standard lung radiation dose constraints, which keeps the risk of pneumonitis to <20%.12 In both the patients, pneumonitis extended well beyond the prior radiation fields. Patient 1 developed diffuse pneumonitis throughout all lung fields. Patient 2 received radiation to the LUL and mediastinum, but her subsequent pneumonitis localised to the upper lobes, which was worse on the right. Patient 2 was treated off-label with concurrent immunotherapy and radiation, which should not be done outside of a clinical trial, and it remains unclear whether concurrent immunotherapy and radiation leads to increased rates of pneumonitis.

Pneumonitis occurs in roughly 3% of those treated with anti-PD1 or anti-PD-L1 monotherapy.7 Cases are typically mild, but 1% of patients will develop severe (grade 3 or grade 4) pneumonitis. The incidence of severe pneumonitis is highest in patients with NSCLC.13 Here, we report two cases of severe pneumonitis following treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, requiring hospitalisation and subsequent steroid therapy. Both patients had steroid-refractory pneumonitis. Patient 1 improved with infliximab therapy, but patient 2 declined further immunosuppression and subsequently died. In the former case, infliximab was used to successfully salvage steroid-refractory pneumonitis in accordance with current guidelines (figure 1).8–10 However, the immunosuppressive effects of infliximab likely represents a double-edged sword, helping to promote resolution of the pneumonitis, but also blunting the ongoing antitumour immune response initially propagated by nivolumab therapy. The latter case (patient 2) illustrates that pneumonitis can often be fatal, despite optimal treatment. This is consistent with a prior study, which reports that 5 out of 12 patients with grade 3 toxicity ultimately died, despite receiving additional immunosuppression (infliximab and/or cyclophosphamide).7 While the precise factors that make a patient susceptible to developing severe pneumonitis or steroid-refractory pneumonitis remain unclear, prompt recognition of this rare complication remains important to effectively treating patients with cancer with PD-1 inhibitors.

Learning points.

Severe pneumonitis occurs in 1% of patients treated with programmed death 1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies.

Pneumonitis caused by PD-1 inhibitors does not result in pathognomonic radiographic or pathological features.

Drug-induced pneumonitis resulting from PD-1 therapy is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring consideration of alternate diagnoses including infection, malignant lung infiltration and radiation-induced pneumonitis.

Steroids are first-line therapy for severe pneumonitis caused by PD-1 therapy, but some cases of pneumonitis are refractory to steroids and require additional immunosuppression.

Footnotes

Contributors: NA, LM, CH, PP and VP were involved in the care of patients, data acquisition and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. . Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horn L, Spigel DR, Vokes EE, et al. . Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: two-year outcomes from two randomized, open-label, Phase III trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057). J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3924–33. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. . Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. . Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA 2016;315:1600–9. 10.1001/jama.2016.4059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khunger M, Rakshit S, Pasupuleti V, et al. . Incidence of pneumonitis with use of programmed death 1 and programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials. Chest 2017;152:271–81. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutros C, Tarhini A, Routier E, et al. . Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:473–86. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. . Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:709–17. 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immunotherapy-related toxicities (Version 1.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/immunotherapy.pdf (Accessed June 2, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al. . Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1714–68. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, et al. . Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:95 10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diederen BM, Kluytmans JA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, et al. . Utility of real-time PCR for diagnosis of Legionnaires' disease in routine clinical practice. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:671–7. 10.1128/JCM.01196-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks LB, Bentzen SM, Deasy JO, et al. . Radiation dose-volume effects in the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010;76:S70–S76. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishino M, Giobbie-Hurder A, Hatabu H, et al. . Incidence of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor-related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1607–16. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]