Abstract

Objective

To determine research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis which represent the shared priorities of patients, their friends and families, carers and healthcare professionals.

Design/setting

A national (UK) research priority setting partnership.

Participants

Patients over 60 years of age who have experienced a fragility fracture of the lower limb or pelvis; carers involved in their care (both in and out of hospital); family and friends of patients; healthcare professionals involved in the treatment of these patients including but not limited to surgeons, anaesthetists, paramedics, nurses, general practitioners, physicians, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Methods

Using a multiphase methodology in partnership with the James Lind Alliance over 18 months (August 2016–January 2018), a national scoping survey asked respondents to submit their research uncertainties. These were amalgamated into a smaller number of research questions. The existing evidence was searched to ensure that the questions had not been answered. A second national survey asked respondents to prioritise the research questions. A final shortlist of 25 questions was taken to a multistakeholder workshop where a consensus was reached on the top 10 priorities.

Results

There were 963 original uncertainties submitted by 365 respondents to the first survey. These original uncertainties were refined into 88 research questions of which 76 were judged to be true uncertainties following a review of the research evidence. Healthcare professionals and other stakeholders (patients, carers, friends and families) were represented equally in the responses. The top 10 represent uncertainties in rehabilitation, pain management, anaesthesia and surgery.

Conclusions

We report the top 10 UK research priorities in patients with fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis. The priorities highlight uncertainties in rehabilitation, postoperative physiotherapy, pain, weight-bearing, infection and thromboprophylaxis. The challenge now is to refine and deliver answers to these research priorities.

Keywords: adult orthopaedics, fragility fractures, lower limb, priority setting partnership

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of established and transparent James Lind Alliance methodology.

Survey responses from all over the UK with a 50:50 split between healthcare professionals and non-healthcare professionals (patients, carers, family and friends).

While the research priorities are now reported, it is up to the research community and research funding organisations to refine and deliver the answers to these questions.

Introduction

An estimated nine million fragility fractures occurred worldwide in the year 2000, with 50 million people suffering from the sequelae of these fractures.1 Hip fractures alone are expected to rise from 1.31 million in 1990 to an estimated 6.26 million per year globally by 2050.2 In the UK, over 300 000 patients present to hospital with fragility fractures,3 and the associated treatment costs are around 2% of the total healthcare burden in the UK—approximately £3 billion per year.4

Adults with fragility fractures of the lower limb or pelvis usually require treatment in hospital and often have other medical comorbidities, along with complex health and social care needs requiring intervention from a number of healthcare professionals and carers.

There is evidence of a mismatch between the research priorities of patients and healthcare professionals and the research which is actually undertaken and delivered.5–7 This situation is changing. Patient and public involvement (PPI) in research has flourished in the UK, driven by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) such that PPI involvement is now a key part of the design, conduct and delivery of research in health and social care.8

The James Lind Alliance (JLA) is a non-profit organisation hosted by the NIHR with the aim of raising awareness of research which is directly relevant and of potential benefit to patients and treating clinicians. The guiding principle is to bring together patients, carers and clinicians to identify and agree on which research uncertainties are most important. To date, there have been over 50 priority setting partnerships across a range of disciplines with over 100 research topics addressed as a direct result of the JLA priority setting partnerships.9 10

The aim of this work is to establish the research priorities for adults with fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis which represent the shared interests and priorities of patients, their families and friends, carers and healthcare professionals.

Methods

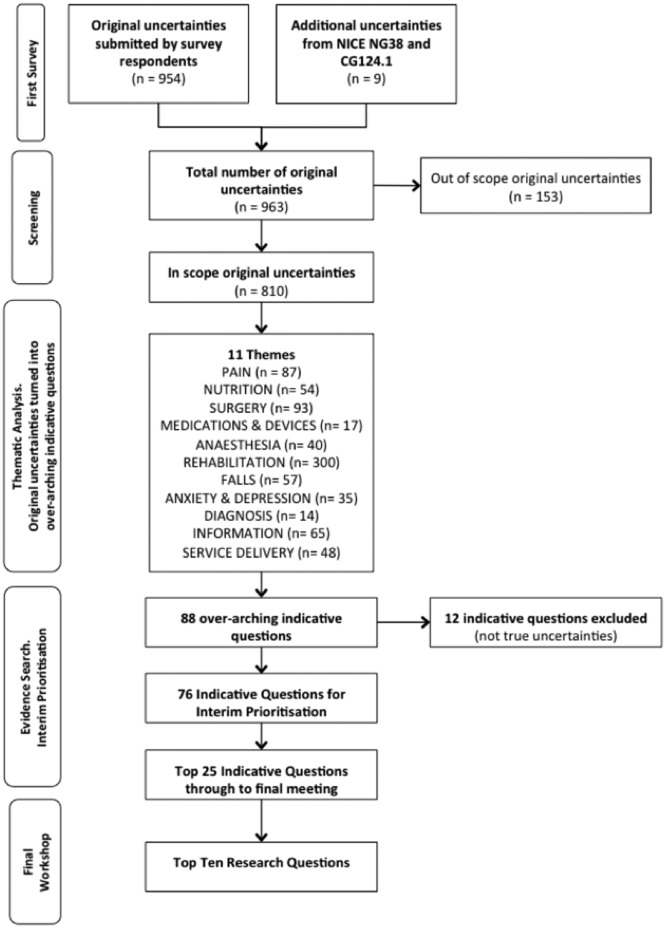

The ‘Broken Bones in Older People’ priority setting partnership (PSP) took place over an 18-month period between August 2016 and January 2018. An overview of the methodology is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of priority setting partnership process. NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Steering group and partner organisations

The clinical lead (MC) initiated the PSP and guided the appointment of a steering group to oversee and contribute to the process. The steering group consisted of patient representatives, healthcare professionals and carers with established links to relevant partner organisations (see online supplementary appendix 1) to ensure that a range of stakeholder groups were represented. Steering group members did so on a voluntary basis and were expected to commit to the whole process where possible. A JLA adviser (CW) supported and guided the PSP as a neutral facilitator to ensure that it was undertaken in a fair and transparent way, encouraging equal contributions from patients, carers and healthcare professionals. This is an important aspect of the JLA process and ensures that all voices are heard and respected throughout the process. An information specialist (MF) managed the data and performed the analysis. This was overseen and advised on by the steering group.

bmjopen-2018-023301supp001.pdf (60.8KB, pdf)

Scope

All research uncertainties related to fragility fractures of the lower limbs and pelvis for patients over 60 years of age were considered in scope. All stages of the patient pathway were eligible including the immediate care of fragility fractures by the emergency services, acute in-hospital care and out-of-hospital care. Primary prevention strategies for fragility fractures were excluded. The decisions about whether submissions were in or out-of-scope were made by the information specialist and subsequently verified by the steering group.

Scoping survey and identification of themes

A national scoping survey asked respondents to submit their research uncertainties and provide some optional basic demographic information (gender, first three letters of their postcode and to identify themselves as either a carer, patient, family/friend of someone over 60 years of age with a fragility fracture or a healthcare professional). The survey was circulated via the steering group and their partner organisations as an open invitation. The survey was available in both paper and online formats (Bristol online survey tool).11 A pilot phase was undertaken to ensure that the survey was clearly written, understandable to all groups and easy to complete. In addition to submissions from survey respondents, we included research uncertainties highlighted in relevant national guidelines published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.12 13

All original submissions were analysed using techniques common to qualitative thematic analysis to define themes and subthemes. The process included initial data immersion (reading and re-reading the submissions), coding of common ideas/themes, identification and naming of themes and subthemes, and a final review to refine the overarching themes. The thematic analysis was undertaken by the information specialist and decisions verified by the steering group. In order to do this, the steering group were given the opportunity to review all of the original submissions under each theme/subtheme. These were then referred to during the verification process.

Indicative questions and evidence search

The overarching themes and subthemes from the thematic analysis were used to generate a smaller number of representative research questions, so-called ‘indicative questions’. These were derived from the original submissions and were designed to summarise the submissions within each subtheme/theme. The information specialist undertook this process. The indicative questions were then reviewed by the steering group along with a selection of the original uncertainties to ensure that they were a true representation, and to ensure that the language used was understandable to all stakeholder groups. For each indicative question, a review of the current research evidence was undertaken to ensure that the proposed indicative questions were ‘true uncertainties’ and had not already been answered by research. MF searched PubMed, the grey literature (www.opengrey.eu), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (www.cochranelibrary.com/about/central-landing-page.hml), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en), Current Controlled trials (http://www.controlledtrials.com/isrctn/), the US National Institute of Health Trials Registry (https://clinicaltrials.gov) and published UK national guidelines.12 13 Indicative questions were excluded if the steering group agreed that high-quality evidence was found (eg, large clinical trials either published or in-progress, published meta-analyses or published national evidence-based guidelines). The remaining indicative questions went through to interim prioritisation.

Interim prioritisation survey

A second national survey asked respondents to state the importance of each indicative question on a five-level Likert scale (1 not important, 2 low importance, 3 no opinion, 4 high importance, 5 extremely important). The survey was available in paper and online formats and went through a pilot phase prior to launch. The second survey was again circulated as an open invitation and not restricted to respondents from the first survey. All indicative questions were ranked (interim prioritisation) by calculating a mean score per question based on the number of responses at each of the five response levels. The results were reviewed by the steering group who decided to take the top 25 to the final workshop.

Final workshop

This was a 1-day multistakeholder workshop involving patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Participants worked in small groups to independently rank the top 25 indicative questions from the interim prioritisation process. The combined results of small group discussions were presented to the whole group. These were considered before a further round of small group discussions. Finally, the whole group came back together again to establish a consensus on the top 10 research priorities for fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis. The role of the steering group at this stage was to ensure that patients and carers were well supported with information and with practical support on the day. As places in the final workshop were limited, the majority of the steering group did not participate in the final workshop.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and carer representatives were actively involved throughout the process; from the initial stages of planning and overseeing the study as part of the steering group, to participation in the final workshop to ensure that the patient and carer ‘voice’ was represented in the final prioritisation. The steering group made particular efforts to approach a diverse range of patient and carer groups across a number of settings to encourage responses to the surveys. The dissemination strategy of this work includes a plain English summary alongside the scientific publication which will be circulated to the partner organisations and PPI groups.

Results

Nine hundred and sixty-three research uncertainties were submitted by 365 respondents to the first survey. After removal of ‘out-of-scope’ uncertainties, there were 810 remaining. Respondents were located throughout the UK. Fifty-one per cent of respondents identified themselves as healthcare professionals and 49% non-healthcare professionals (23% family and friends, 16% patients, 10% carers).

Eleven themes were identified: pain, nutrition, surgery, medications and devices, anaesthesia, rehabilitation, falls, anxiety and depression, diagnosis, information and service delivery. From these themes, 88 indicative questions were formulated to represent the original uncertainties. Twelve indicative questions were excluded following a search of the research evidence, leaving 76 indicative questions for interim prioritisation.

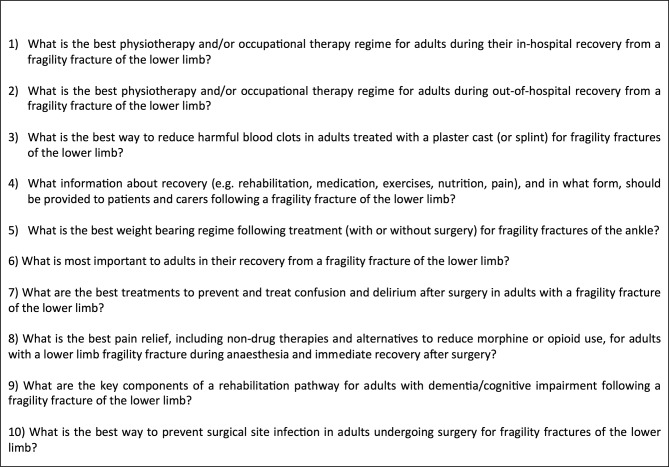

The interim prioritisation survey received 209 responses from different regions of the UK, of which 47% identified themselves as healthcare professionals and 53% non-healthcare professionals (15% family and friends, 28% patients, 10% carers). Each question was scored based on the responses to interim prioritisation and ranked from positions 1 to 76. The ranking was reviewed by the steering group, and the top 25 questions were taken to the final prioritisation workshop where a consensus was reached on the top 10 research priorities (see figure 2 for priorities 1–10 and online supplementary appendix 2 for priorities 11–25). You can see the full list of original uncertainties and indicative research questions at the following websites: www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/broken-bones-in-older-people/ www.ndorms.ox.ac.uk/research-groups/oxford-trauma/broken-bones-in-older-people.

Figure 2.

The top 10 UK research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis.

Discussion

We have reported the results of a UK PSP with the JLA and identified the top 10 research priorities in patients with fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis. These research priorities represent the shared interests of the multiple stakeholders affected by fragility fractures: patients, family and friends, carers and healthcare professionals. The top 10 priorities emphasise the lack of evidence to guide ‘rehabilitation’ following fragility fracture and highlight a number of unanswered questions in postoperative physiotherapy, weight-bearing and rehabilitation pathways for patients with cognitive impairment.

This study has a number of strengths. This is the first study to report national research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis in partnership with the JLA. These priorities compliment research priorities highlighted by national guidelines in this area which also highlight research uncertainties in rehabilitation and physiotherapy.12Patient and carers were actively involved at all stages of the process to ensure that the patient voice was heard and remained at the centre of our efforts. We used the established and transparent JLA methodology to conduct this PSP. All the original research submissions and the indicative questions (76 in total) are available on the JLA website.9 The number of survey responses were comparable with other JLA PSPs,14 and we achieved a 50:50 balance between responses from healthcare professionals and non-healthcare professionals. Responses have been submitted from all over the UK, and we are therefore confident that this work represents a national viewpoint.

Fragility fractures affect frail older people disproportionately. Considerable efforts were required to ensure that all patient groups were able to access and respond to our national surveys. These strategies included accessing clinical environments (eg, General Practice surgeries, hospital outpatient clinics) with paper surveys and sending our online survey link via the mailing lists of national organisations such as the National Osteoporosis Society to ensure as widespread inclusion of patient groups as possible. However, despite these efforts, it is possible that the research priorities reported still under-represent the frailest group which includes those with permanent cognitive impairment for whom responding to a survey may not be possible. However, we are encouraged to see a research uncertainty in the top 10 specifically directed towards identifying the key components of a rehabilitation pathway for those with chronic cognitive impairment.

We found that research questions which were very specific—which identified the intervention and comparator within the question—tended to attract a lower ranking than more general questions asking a broader less well-defined research question. For example, questions asking ‘What is the best physiotherapy?’ were found to attract more votes than more specific questions comparing two specific interventions (eg, ‘Which is better, tai chi or standard physiotherapy?’). This may reflect an opinion by survey respondents that broader questions may have wider impact and cover multiple interventions. Nevertheless, we felt it was important to strike a balance between more general questions and questions about specific interventions such that the spectrum of the original submissions was accurately reflected. Future prioritisation partnerships will need to consider this aspect of the process and decide on the right balance between inclusion of specific versus general indicative questions.

This work has highlighted the top research questions in lower limb and pelvic fragility fracture research. It is now up to the research community and research funders to refine and deliver the answers to these questions. We hope this work will shape the research landscape in this area and help to deliver meaningful advances in the quality-of-life and care of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the patients, their families and friends, carers and healthcare professionals who submitted responses to the national surveys. In addition, they would like to thank the partner organisations (online supplementary appendix 1) who supported and promoted this work, the JLA for support and guidance throughout the process and all attendees at the final workshop who worked tirelessly to achieve a consensus on the top 10 research questions: (Vicky Crawford, Anita Vowles, Robert Crouch, Andrew McAndrew, Nigel Rees, Helen Wilson, Pippa Ellery, Cliff Shelton, Debs Smith, Josephine Rowling, Karen Keates, Stella Saunders, Sheila Holmes, Jean Maston, Shirley MacWhirter, Thelma Sanders, Sue Bremner-Milne, Diane Hackford, John Cocker, Sheela Upadhyaya, and Toto Anne Gronlund).

Footnotes

Contributors: MAF analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. LA, JG, AM, RG, PB, SW, MB, XG, TC, DK, RSK, CW and MLC provided significant edits to the manuscript and approved the data analysis. MAF, LA, JG, AM, RG, PB, SW, MB, XG, TC, DK, RSK, CW and MLC have all made significant contributions to the design, implementation and delivery of this research. All authors (MAF, LA, JG, AM, RG, PB, SW, MB, XG, TC, DK, RSK, CW, and MLC) have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: The British Orthopaedic Association and the UK Orthopaedic Trauma Society made financial contributions to support the Priority Setting Partnership. The Partnership was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: MLC is a member of the NIHR HTA General Board.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This work did not require ethics approval as per the JLA guidance and guidance published by the NHS National Patient Safety Agency National Research Ethics Service.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Supplementary data including all submitted original research uncertainties and out of scope submissions can be found on the JLA website at http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/broken-bones-in-older-people/

References

- 1. Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:1726–33. 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 1992;2:285–9. 10.1007/BF01623184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. British Orthopaedic Association. The care of patients with fragility fracture. London: British Orthopaedic Association, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:897–902. 10.1007/s00198-004-1627-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, et al. Patients', clinicians' and the research communities' priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem 2015;1:2 10.1186/s40900-015-0003-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tallon D, Chard J, Dieppe P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 2000;355:2037–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02351-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boddy K, Cowan K, Gibson A, et al. Does funded research reflect the priorities of people living with type 1 diabetes? A secondary analysis of research questions. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016540 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health, 2015. Going the extra mile: improving the nation’s health and wellbeing through public involvement in research www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/documents/ Extra%20Mile2.pdf (accessed 9 Sep2017).

- 9. James Lind Alliance, 2017. James Lind Alliance priority setting partnerships www.jla.nihr.ac.uk (accessed 5 Aug2018).

- 10. Boney O, Bell M, Bell N, et al. Identifying research priorities in anaesthesia and perioperative care: final report of the joint National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia/James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010006 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bristol online survey. http://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk (accessed 1 Mar 2018).

- 12. NICE. Hip fracture: management. London: NICE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. NICE. Fractures (non-complex): assessment and management (NG38). London: NICE, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, et al. Research priorities for shoulder surgery: results of the 2015 James Lind Alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010412 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023301supp001.pdf (60.8KB, pdf)