Abstract

Background and Aims:

Various adjuvants have been added to local anesthetics in single shot blocks so as to prolong the duration of postoperative analgesia. The present study was conceived to evaluate the effect of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine for institution of supraclavicular brachial plexus block.

Material and Methods:

Ninety adult patients (ASA physical status I, II) scheduled for elective upper limb surgeries under ultrasound-guided subclavian perivascular brachial plexus block were allocated randomly into two groups; the study was designed in double-blind fashion. All patients received 20 ml 0.75% ropivacaine, in addition, patients in group A (n = 43) received 2 ml 0.9% normal saline and those in group B (n = 44) received dexmedetomidine (1 μg/kg body weight); total volume was made up to 22 ml with sterile 0.9% saline in both groups. The onset and duration of sensory and motor blocks, time to first request of analgesia, total dose of postoperative analgesic administration, and level of sedation were also studied in both the groups. All the data were analyzed by using unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

Sensory and motor block durations (613.34 ± 165.404 min and 572.7 ± 145.709 min) were longer in group B than those in group A (543.7 ± 112.089 min and 503.26 ± 123.628 min; P < 0.01). Duration of analgesia was shorter in group A (593.19 ± 114.44 min) compared to group B (704.8 ± 178.414 min; P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Addition of dexmedetomidine to 0.75% ropivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block significantly prolongs the duration of analgesia.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, ropivacaine, supraclavicular brachial plexus block, subclavian perivascular block, ultrasound

Introduction

Various adjuvants have been added to local anesthetics to increase the efficacy and duration of blocks, extending analgesia in the postoperative period, while minimizing systemic adverse effects along with a reduction in the total dose of local anesthetic used. Dexmedetomidine, a potent α2 adrenocepter agonist, is approximately eight times more selective towards the α2 adrenoceptor than clonidine.[1] In humans, dexmedetomidine has shown to prolong the duration of block and postoperative analgesia when added to local anesthetic in various regional blocks.[2] Dexmedetomidine has been studied in brachial plexus block as a sole agent or in comparison with other adjuvants concomitantly with local anesthetic solution.[3] The optimal dose of dexmedetomidine as adjuvant in nerve blocks is still to be determined.

The present study was conceived to examine the effect of adding dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to 0.75% ropivacaine for supraclavicular brachial plexus block (SCB) in patients undergoing upper limb orthopedic surgeries. The primary outcome was the duration of analgesia. Secondary outcomes include the time to onset of and duration of sensory and motor blockade, and side-effects, if any.

Material and Methods

This study was conducted in a Tertiary Care Centre from April 2015 to September 2015 over a period of 6 months. Prior ethical permission was taken from the institutional ethical committee. This prospective, randomized, double-blind study included 90 American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II patients of either sex, aged 20–50 years, weighing 50–80 kg who underwent various elective surgeries on the upper extremities below the mid-humerus level. Patients who had local pathology at the site of injection, pre-existing peripheral neuropathy of upper limb, suspected brachial plexus injury, history of any systemic disease, convulsion, known hypersensitivity to the study drugs, bleeding disorders, patients on adrenoreceptor agonist or antagonist therapy, alcohol or drug abusers, pregnant women, and psychiatric patients were excluded from the study. Patients with duration of surgery >150 minutes or <30 minutes, patients in whom successful block was not obtained 30 minutes after injection, those who showed allergic reaction to the study drugs, and those who did not cooperate or refused to participate in the study were also excluded.

Preanesthetic check-up (PAC) was done a day before the surgery which involved a thorough assessment of the patient. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients for performance of USG-guided SCB after a complete explanation of the study protocol and the procedure. Visual analogue scale (VAS) 0–10 was also explained to the patients.

Patients were randomized on the day of the surgery to one of the two groups A or B by chit in box method. Patients themselves pulled out the chit from the box. Medications were prepared by one anesthesiologist and observations were made by another anesthesiologist who was blinded to the drug administered.

Patients were divided into two groups with 45 patients in each. Both groups received a total injectate of 22 ml. Group A had 45 patients who received 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine (Ropin, Neon Laboratories, Mumbai) and 2 ml normal saline. In Group B, 45 patients received 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine with 1 μg/kg body weight dexmedetomidine (Dextomid, Neon Laboratories, Mumbai); sterile 0.9% saline was added to make the total volume 22 ml.

The patients were placed in a supine position, with the head turned away and the ipsilateral arm adducted. Skin was prepared with 10% povidone-iodine solution. All the patients received USG [SonoSite, MicroMaxx machine with high frequency (8–13 MHz) linear probe (covered with a sterile dressing)] guided subfascial intracluster subclavian perivascular brachial plexus block by an experienced anesthesiologist different from the one assessing the patients both intra- and postoperatively.

Patients were evaluated for onset of sensory block every 3 min after completion of injection till 30 minutes and then every 30 min after the end of surgery till the first 12 hours, and thereafter, hourly until the block had completely worn off. The sensory block was assessed by the pinprick sensation with a blunt 25-G hypodermic needle in all dermatomes innervated by the brachial plexus (C5-T1) in the distribution of median, radial, ulnar, and musculocutaneous nerves. Sensory block was graded as: Grade 0 = Sharp pin sensation felt, Grade 1 = Analgesia, dull sensation felt, Grade 2 = Anesthesia, no sensation felt.[4] The onset time of the sensory block was taken as the time from injection of local anesthetic into the brachial plexus to obtunding of pinprick sensation, i.e., sensory block grade 1. Duration of sensory block was defined as the time interval between the end of administration of local anesthetic and complete recovery from anesthesia in all dermatomes.

Motor blockade was assessed using Modified Bromage scale (MBS) for upper extremities: Grade 0 – able to raise the extended arm to 90° for a full 2 s; Grade 1 – Able to flex the elbow and move the fingers but unable to raise the extended arm; Grade 2 – Unable to flex the elbow but able to move the fingers; Grade 3 – Unable to move the arm, elbow, or fingers.[5] The onset of motor block was defined as the time from injection to motor paralysis equivalent to Bromage score 2. The duration of motor block was defined as the time between onset of motor block to complete return of motor power, i.e., Bromage 0.

Patient's perception of pain was assessed using VAS (0–10), with 0 being no pain at all and 10 being the worst pain imaginable.[6] VAS score was measured at 6 h, 12 h, and 18 h.

Intraoperative sedation was determined with the Ramsay sedation scale as follows: (1) Patient anxious and agitated or restless or both; (2) Patient cooperative, oriented, and tranquil; (3) Patient responds to commands only; (4) Brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus; (5) Sluggish response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus; (6) No response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus.[7]

Intraoperatively, heart rate, noninvasive blood pressure, and SpO2 were monitored throughout the procedure and also during the postoperative period. Hypotension was defined as 20% decrease in systolic blood pressure from the baseline. Bradycardia was defined as heart rate < 60 beats/min. Tachycardia was defined as heart rate > 100 beats/min.

Rescue analgesia was given on patient's demand. Total duration of analgesia was defined as the time from commencement of block to the patient's first request for rescue analgesic (VAS >4). Injection diclofenac sodium (Dynapar AQ, Troikaa Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Ahmedabad) 75 mg IV infusion was given as rescue analgesic.

The sample size was calculated based on a pilot study on 10 patients in each group. To detect clinically significant difference between the two groups (2.5 ± 4) min in onset of motor block at 95% significance and 80% power, the required sample size was 84 participants or 42 participants in each group. To make good for attrition rate, 45 patients in each group were included for the study.

Raw data were entered into a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet and analyzed using standard statistical software SPSS® statistical package version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data, i.e., ASA grade, type of surgery, and the incidence of adverse events (hypotension, bradycardia, dryness of mouth, nausea, vomiting, and headache) were presented as percentage and proportions. These data were compared in two groups, and the difference in the proportion was inferred by Pearson's chi-square test. Demographic data (age, weight), duration of surgery, VAS score, total duration of motor block, and analgesia were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. These data were compared between the two groups, and differences in means were inferred by unpaired t-test. For significance, P < 0.05 was considered as significant for both types of data.

Results

We recruited 45 participants per group and there were no dropouts. However, 3 cases were excluded from our survey due to inadequate nerve block, and we had to consider general anesthesia as the second plan. Thus, final data analysis was performed on 87 patients (Group A = 43 patients, Group B = 44 patients).

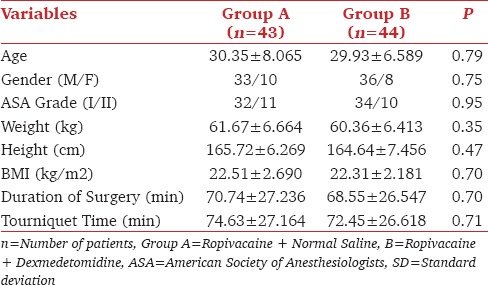

Both the groups were comparable in terms of demographic profiles (age, gender, ASA grade, weight, height, BMI) and operative data (duration of surgery and tourniquet time) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

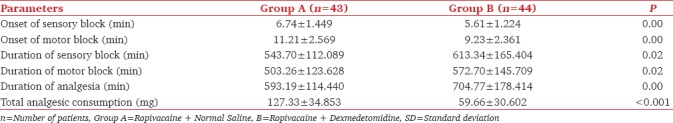

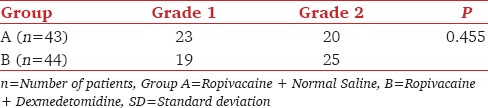

The sensory and motor block onset was shorter in group B (5.61 ± 1.224 min and 9.23 ± 2.361 min) compared to group A (6.74 ± 1.449 min and 11.21 ± 2.569 min) (P < 0.001) [Table 2]. In Group A, most of the patients had Grade 1 whereas in Group B majority had Grade 2 sensory block at the time of commencement of surgery. Chi-square test was applied between the groups and was statistically not significant [Table 3]. The durations of sensory as well as motor block were significantly prolonged in the group receiving dexmedetomidine (613.34 ± 165.404 min and 572.70 ± 145.709 min) as compared to group A (543.70 ± 112.089 min and 503.26 ± 123.628 min) [Table 2]. The duration of analgesia was significantly longer in group B (704.77 ± 178.414 min). The difference between the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Block characteristics

Table 3.

Grade of Maximum Sensory Block at the time of commencement of surgery (no. of patients)

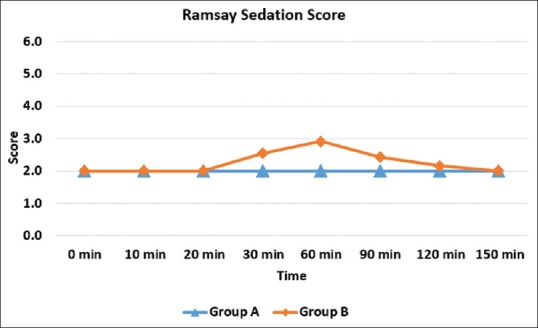

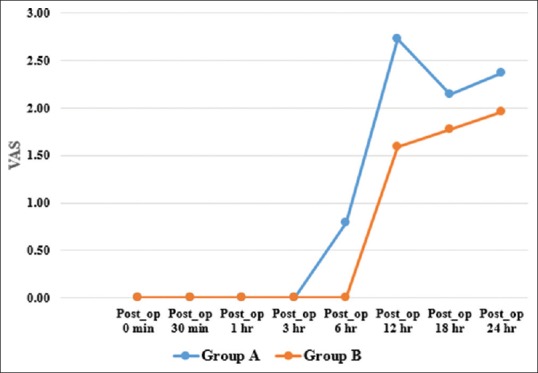

There was higher sedation score in Group B from 20 minutes to 120 minutes time point which was statistically significant (P < 0.05) [Figure 1]. Patients in Group B had zero VAS score for a longer duration than those in Group A. Comparison of mean VAS scores between the two groups was statistically significant up to 12 hours (P < 0.001) [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Intraoperative Sedation Score

Figure 2.

VAS Score

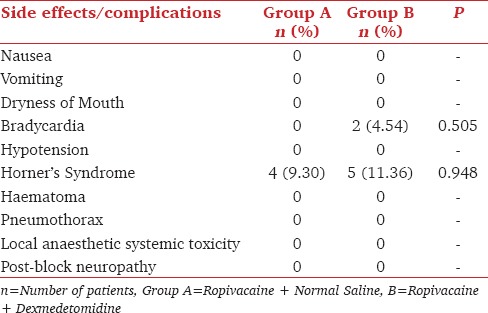

Two patients had bradycardia in the dexmedetomidine group. There was incidence of Horner's syndrome in both the groups which was statistically not significant [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of side effects or complications [n (%)]

Discussion

The result of the present randomized controlled trial clearly suggests that addition of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine for USG-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block prolongs the duration of analgesia as well as sensory and motor block.

We performed USG-guided supraclavicular blocks with 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine compared to 30 ml by Madhusushana et al.[8] and Rashmi et al.[9] Thus, we avoided the risk of increased total dose of local anesthetics. Many authors favor the hypothesis that dexmedetomidine prolongs the effect of local anesthetic by blocking the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih current).[10] We used 1 μg/kg dexmedetomidine along with ropivacaine which is supported by the study reported by More et al.[11]

In our study, we have observed that addition of dexmedetomidine significantly shortened the onset of sensory and motor block. This observation well matches with Kathuria et al.[12] Das et al.[13] who found that onset of sensory as well as motor blocks was earlier in dexmedetomidine group though the differences were not statistically significant. However, the drugs and criteria selected for onset of motor block was different from our study. The duration of motor and sensory block was also significantly prolonged by addition of dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine, which is consistent with most of the trials published in the literature.[12] The mean duration of analgesia (demand of first rescue analgesia) in dexmedetomidine-ropivacaine group was significantly longer than duration in ropivacaine only group, which is supported by the study done by Bharti et al.[14] In their study, dexmedetomidine at 1 μg/kg provided an analgesic effect that lasted as long as 17 hours which is 5 hours more than the duration of control group (12 hours).

The sedative effect of perineural dexmedetomidine may be due to the partial vascular uptake of dexmedetomidine and its transport to the central nervous system where it acts and produces sedation. In our study, sedation scores were higher in patients receiving dexmedetomidine compared to the control group. Intraoperatively, more sedation was observed from 20 minutes to 120 minutes’ time point in the dexmedetomidine group. The modified Ramsay sedation score for dexmedetomidine group was either 3/6 or 4/6 in a majority of the cases, while that for control group it was 2/6. No patient experienced airway compromise or required airway assistance because of sedation. Recently, Kwon et al.[15] evaluated the sedative effect of perineural dexmedetomidine for supraclavicular brachial plexus block using the bispectral index (BIS) and observed that it corresponds to a BIS value of 60, from which patients are easily awakened in a lucid state.

None of the patient had hypotension (defined by decrease in blood pressure by 20%) and maintained the hemodynamic parameters well within the normal range, which is similar to study conducted by Das et al.[13] and Agarwal et al.[3] Bradycardia (heart rate less than 60/min) was observed in two patients in dexmedetomidine group which responded to single dose of injection atropine sulphate. This is similar to the study conducted by Das et al.[13] and Kathuria et al.[12] Horner syndrome was noted in both the groups, but the difference was statistically insignificant (P > 0.05) which is similar to the study of Das et al.[13] There was no episode of hypoxemia or respiratory depression or pneumothorax during the 24-hour period postoperatively. Signs of local anesthetic systemic toxicity, inflammation of the puncture site or nerve lesion, pruritus, or urinary retention were not observed in any patient of either group. Patient acceptance was good in all the patients studied, and no complications were observed at postoperative follow-up.

We found significantly important results despite a small sample size. We suggest future studies to be undertaken with a larger population size. Another area of concern is that prolonged motor blockade by dexmedetomidine is detrimental in day-care settings where early mobilization is desirable, as it prolongs the duration of motor block significantly even at a dose of 30 μg.[16]

Conclusion

Addition of dexmedetomidine (1 μg/kg) to 0.75% ropivacaine for USG-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block is highly effective in hastening the onset and prolonging the duration of anesthesia and analgesia. So, the patient remains comfortable in the postoperative period with considerable therapeutic benefit and without any potential side-effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bajwa SJ, Kulshrestha A. Dexmedetomidine: An adjuvant making large inroads into clinical practice. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:475–83. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hussain N, Grzywacz VP, Ferreri CA, Atrey A, Banfield L, Shaparin N, et al. Investigating the Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine as an Adjuvant to Local Anesthesia in Brachial Plexus Block: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 18 Randomized Controlled Trials. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:184–96. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal S, Aggarwal R, Gupta P. Dexmedetomidine prolongs the effect of bupivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:36–40. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.125701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur A, Singh RB, Tripathi RK, Choubey S. Comparison Between Bupivacaine and Ropivacaine in Patients Undergoing Forearm Surgeries Under Axillary Brachial Plexus Block: A Prospective Randomized Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:UC01–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/10556.5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cline E, Franz D, Polley RD, Maye J, Burard J, Pellegrini J. Analgesia and effectiveness of Levobupivacaine compared with Ropivacaine in patients undergoing an axillary brachial plexus block. AANA J. 2004;72:339–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EK, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:17–24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sessler CN, Jo Grap M, Ramsay MA. Evaluating and monitoring analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit. Critical Care. 2008;12(Suppl 3):S2. doi: 10.1186/cc6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhusudhana R, Kumar K, Kumar R, Potli S, Karthik D, Kapil M. Supraclavicular brachial plexus block with 0.75% ropivaciane and with additives tramadol, fentanyl- a comparative pilot study. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011;2:1061–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rashmi HD, Komala HK. Effect of Dexmedetomidine as an Adjuvant to 0.75% Ropivacaine in Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block Using Nerve Stimulator: A Prospective, Randomized Double-blind Study. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11:134–9. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.181431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brummett CM, Norat MA, Palmisano JM, Lydic R. Perineural Administration of Dexmedetomidine in Combination with Bupivacaine Enhances Sensory and Motor Blockade in Sciatic Nerve Block without Inducing Neurotoxicity in the Rat. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:502–11. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182c26b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.More P, Basavaraja, Laheri V. A comparison of dexmedetomidine and clonidine as an adjuvant to local anaesthesia in supraclavicular brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries. JMR. 2015;1:142–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathuria S, Gupta S, Dhawan I. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015;9:148–54. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.152841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das A, Majumdar S, Halder S, Chattopadhyay S, Pal S, Kundu R, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine as adjuvant in ropivacaine-induced supraclavicular brachial plexus block: A prospective, double-blinded and randomized controlled study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8(Suppl 1):S72–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.144082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Bharti N, Sardana DK, Bala I. The Analgesic Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine as an Adjunct to Local Anesthetics in Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1655–60. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon Y, Hwang SM, Lee JJ, Kim JH. The effect of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine on the bispectral index for supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015;68:32–6. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2015.68.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi R, Shah A, Patel I. Use of dexmedetomidine along with bupivacaine for brachial plexus block. Natl J Med Res. 2012;2:67–9. [Google Scholar]