ABSTRACT

Background

Fellowships in global health are increasingly popular and seek to equip physicians with the skills necessary to be effective global health practitioners. Little objective guidance exists on which skills make graduates competitive applicants from the perspective of potential global health employers.

Objective

We sought to provide objective evidence for the qualifications that make applicants competitive for global health positions by analyzing the listed qualifications for current job openings in large global health organizations.

Methods

The websites of 48 global health employers were systematically searched for current job postings between May and August 2017. Jobs were included for analysis if a medical degree was listed among the primary degrees accepted, and the job was based primarily in a low- or middle-income country.

Results

A total of 5849 employment opportunities were posted during the search period, and 81 (1.4%) of these met inclusion criteria. Twenty-two (27%) jobs required and 35 (43%) preferred a relevant master's degree. Few jobs requested a candidate with a PhD and none mentioned tropical medicine training as a requirement or preference. Twenty-three jobs (28%) required and 19 (23%) preferred candidates to speak another language. Most jobs (69%, 56 of 81) required more than 5 years of relevant experience. Only 11 (13%) jobs were primarily clinical positions.

Conclusions

For physicians pursuing a career in global health, most publicly searchable jobs require substantial previous experience and involvement in global health activities beyond clinical practice. Master's degree and language skills are frequently requested candidate qualifications.

What was known and gap

Despite growth in global health fellowships, little guidance exists for graduates on skills that make them competitive for global health jobs.

What is new

Master's degrees and language skills were frequently requested candidate qualifications, and most jobs required years of prior work experience.

Limitations

Search assessed major global health employers and may have omitted faith-based organizations and nongovernmental organizations.

Bottom line

Most publicly advertised global health positions required previous experience and involvement in global health activities beyond clinical work.

Introduction

Over the past 15 years, postresidency fellowships in global health have rapidly spread across the United States. In 2000, few international fellowships existed, and most were in emergency medicine. Between 2012 and 2017, global health fellowships grew from 80 programs in 7 specialties to 125 programs in 9 specialties.1,2 Fellowships have generally arisen independently, taking advantage of various institutional strengths and cross-national partnerships. Currently, global health fellowships are not accredited, and there are few structures to ensure standardization of training.3 This has resulted in a wide variety of experiences, learning objectives, and outcomes for global health fellowship programs. Published literature for learning outcomes in global health fellowships exists in certain specialties and provides some valuable guidance for program directors and trainees.4–8

While many fellowship graduates accept academic faculty positions after graduation, others seek employment with global health employers.1 The purpose of a global health fellowship is to equip physicians with the skills for a successful career in global health development, and many programs require or encourage fellows to obtain a master's-level degree, have tropical medicine certification, or gain competency in a foreign language. At the same time, there is little objective guidance on which of these skills make graduates competitive applicants from the perspective of future global health employers. Results from a 2016 survey revealed that 85% of responding global health employers agreed that graduates of global health graduate programs could be better prepared in nonclinical skills, yet the exact mechanisms by which employers expect learners to obtain these skills remain unclear.9

The purpose of this study was to provide objective evidence for the qualifications that make applicants competitive for global health positions by analyzing requested qualifications of currently available job openings in large global health organizations and comparing these qualifications with current training provided by global health fellowships.

Methods

For this study, we identified 48 large global health organizations from 2 sources: a list of 40 top vendors published by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and a list of major global health nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).10,11 One of 3 physicians reviewed each of the 47 websites for job opportunities between May and July 2017. Jobs were included in the analysis if a medical degree was listed among the primary degrees accepted for the job and the job was based primarily in a low- or middle-income country (as defined by the World Bank).12 Jobs based out of an organization's headquarters in a high-income country or that required the applicant to be a national of the country where the job was located were excluded.

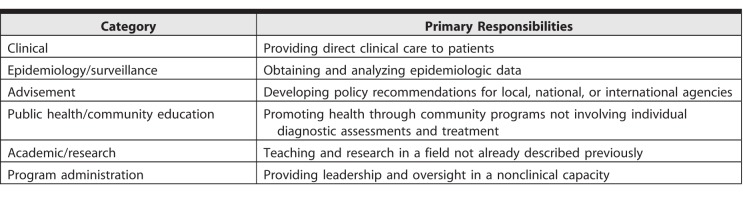

For each job meeting inclusion criteria, we entered the following data points into a spreadsheet: language requirements (other than English); years of experience required (divided 0–1, 1–5, 6–10, or > 10 years); master of public health (MPH), PhD, or a tropical medicine diploma; and requirements for postgraduate courses. Jobs were also categorized as fitting into 1 or more of 6 main categories: program administration, clinical, epidemiology/surveillance, advisement, academic/research, and public health/community education (Table). In addition, active global health fellowships were identified using an online database.2 Their respective websites were reviewed to identify the number of fellowship programs offering an MPH, PhD, tropical medicine diploma, or language acquisition as part of the curriculum. Fellowships were included in the evaluation if they were university or hospital based, were open only to trained physicians, were currently active, and had a working website.

Table.

Job Categories and Descriptions

Results

A total of 48 global health employers were searched. Six organizations were eliminated due to lack of employment opportunities posted on the website or an inoperable website. One organization did not have a website; 2 organizations posted only unpaid volunteer opportunities on their website; 2 organizations had no jobs available at the time of the search; and 1 organization did not post specific jobs and used an online application and interview process for placement. The remaining 42 organizations had 5881 employment opportunities posted to their websites over the search period, and 81 (1.4%) of these met inclusion criteria. Seventeen organizations had at least 1 job meeting inclusion criteria, with a range of 1 to 18 relevant jobs per organization (list provided as online supplemental material).

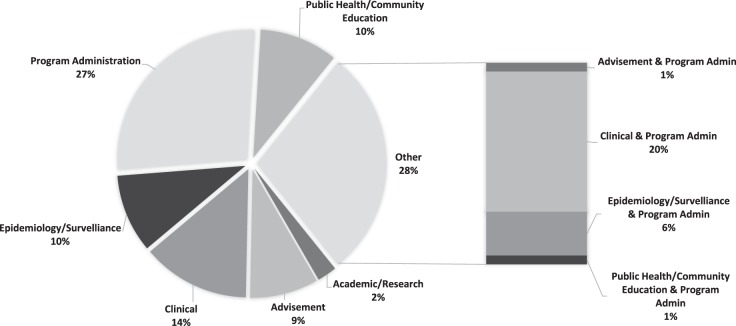

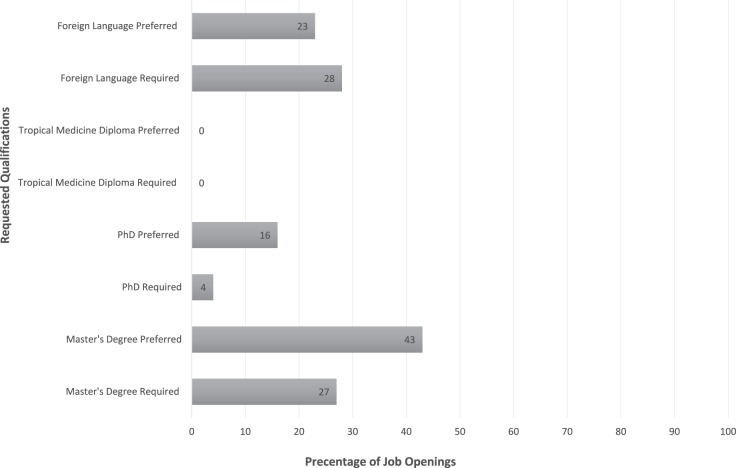

Twenty-two jobs were categorized as program administration, 11 clinical, 8 epidemiology/surveillance, 8 public health/community education, 7 advisement, and 2 academic/research. The remaining 23 jobs were a combination of the aforementioned categories (Figure 1), with the most common combination (16 of 23) being program administration and clinical. Twenty-two (27%) jobs required an MPH or equivalent, and 35 (43%) preferred a candidate with an MPH degree. Three (4%) jobs required and another 13 (16%) preferred a candidate with a PhD. No job listed a tropical medicine diploma as a requirement or preferred candidate qualification. Twenty-three (28%) jobs required that the applicant have a working knowledge or fluency in another language, and another 19 (23%) indicated preference for a candidate with a language skill (Figure 2). French (9 jobs requiring and 4 jobs preferring) and Portuguese (7 jobs requiring and 4 jobs preferring) were the most commonly mentioned languages.

Figure 1.

Types of Jobs Available

Figure 2.

Percentage of Job Openings With Requested Qualifications

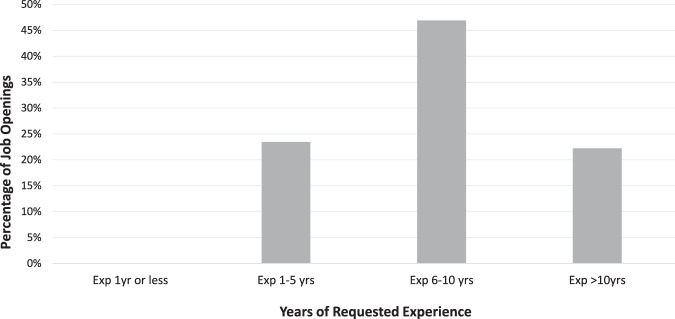

Seventy-five (93%) job openings requested candidates with specific prior years of experience. Nineteen (23%) jobs requested a candidate with 1 to 5 years of experience, 38 (47%) requested a candidate with 6 to 10 years of experience, and 18 (22%) requested more than 10 years of experience (Figure 3). Forty-one (51%) job openings stipulated a candidate's previous experience in a similar international setting.

Figure 3.

Years of Required Experience

A total of 91 active global health fellowships were identified using the global health fellowship online database.2 Emergency medicine had the highest number of active fellowships (n = 38), followed by family medicine (n = 18), pediatrics (n = 8), women's health (n = 8), internal medicine (n = 7), anesthesia (n = 4), surgery (n = 3), and psychiatry (n = 1). Four fellowships were categorized as interdisciplinary and accepted applicants from a range of specialties. Fifty-eight fellowships (64%) offered an MPH, 28 (31%) offered a tropical medicine diploma, 3 (3%) offered some degree of language acquisition, and 1 (1%) offered a PhD as a part of the curriculum. Emergency medicine fellowships were the most likely to offer advanced training, with 95% (36 of 38) of those fellowships offering an MPH and 45% (17 of 38) offering a tropical medicine diploma.

Discussion

In this study of online posted jobs in large global health organizations, few global health positions offered were purely clinical in nature, which suggests that physicians working abroad in clinical settings are expected to be involved in administrative or public health roles. This finding highlights the importance of postresidency training in nonclinical skills, which is consistent with a previous survey of global health employers.9 A majority of postresidency global health fellowships reviewed include obtaining a master's degree in public health or a related field, in keeping with the finding that most available jobs either required or preferred such a degree. The findings also suggest that formal training in tropical medicine may be overemphasized in postgraduate fellowships, while language acquisition may be an underrepresented area for many programs.

One of the most striking findings is that a majority of jobs required more than 5 years of experience. This is more experience than a physician can obtain during a traditional fellowship, as the majority last 2 years. It is likely that entry-level positions for physicians in global health are often obtained in another manner, such as networking or promotion from an internship position within an organization. Although it is difficult to measure the impact that networking with other global health professionals has on future career advancement, it is likely a major advantage of fellowships. Fellowship training itself was not mentioned as a candidate qualification in any of the jobs meeting inclusion criteria, raising the question of the level of knowledge employers have about global health fellowships.

This study has limitations. Organizations whose websites were searched were limited to those included in 1 of 2 lists: global health NGOs referenced from a global health programming book and the most common USAID vendors.10,11 A centralized database of global health organizations does not exist, our analysis may have excluded small global health NGOs and faith-based organizations, and our methodology was limited to jobs posted on the organizations' websites. Finally, we did not examine the preferred or required qualifications for fellowship graduates seeking academic positions, which is the most common career path for fellowship graduates.

Future research is needed to assess global health employers' knowledge of global health fellowship programs and their perceived value, which could also be helpful in informing global health curricula.

Conclusion

For global health fellowship graduates seeking employment with large global health employers, most publicly searchable jobs require substantial previous experience. Master's degree or language skills were desirable candidate qualifications, while having a PhD or tropical medicine diploma were infrequently requested. Most global health positions identified required physicians to be involved in program administration or public health practice in addition to clinical activities.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Nelson BD, Izadnegahdar R, Hall L, et al. Global health fellowships: a national, cross-disciplinary survey of US training opportunities. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(2):184–189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00214.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Fellowships. Database of current global health fellowship programs. 2018 http://globalhealthfellowships.org/database.html Accessed August 23.

- 3.Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Fellowship approval program: global EM fellowship. 2018 http://www.saem.org/resources/services/fellowship-approval-program/global-em-fellowship Accessed August 23.

- 4.VanRooyen MJ, Clem KJ, Holliman CJ, et al. Proposed fellowship training program in international emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(2):145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson BD, Herlihy JM, Burke TF. Proposal for fellowship training in pediatric global health. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1261–1262. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leow JJ, Kingham TP, Casey KM, et al. Global surgery: thoughts on an emerging surgical subspecialty for students and residents. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(3):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rayess FE, Filip A, Doubeni A, et al. Family medicine global health fellowship competencies: a modified delphi study. Fam Med. 2017;49(2):107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayram J, Rosborough S, Bartels S, et al. Core curricular elements for fellowship training in international emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(7):748–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudy S, Wanchek N, Godsted D, et al. The PHI/GHFP-II employers' study: the hidden barriers between domestic and global health careers and crucial competencies for success. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82(6):1001–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.USAID. Top 40 vendors. 2018 https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/budget-spending/top-40-vendors Accessed August 23.

- 11.Abelson J, Bertani L, Cherniak W, et al. Networking in global health: organizations, meetings and funding. In: Evert J, Drain P, Hall T, editors. Developing Global Health Programming: A Guidebook for Medical and Professional Schools 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Global Health Education Collaborations Press; 2014. pp. 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2018 https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Accessed August 23.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.