Short abstract

Background

Emerging research suggests that social media has the potential in clinical settings to enhance interaction with and between pediatric patients with various conditions. However, appearance norms and weight stigmatization can make adolescents with obesity uncomfortable about using these visual-based media. It is therefore important to explore these adolescents’ perspectives to identify the implications and concerns regarding the use of social media in clinical settings.

Objective

To explore the experiences of adolescents in treatment for obesity in terms of how they present themselves on social media, their rationale behind their presentations, and their feelings related to self-presentation.

Methods

Interviews were conducted with 20 adolescents enrolled in a pediatric outpatient obesity clinic, then transcribed and categorized using qualitative content analysis and Goffman’s dramaturgical model. Participants used a screen-recorded laptop to demonstrate their online self-presentation practices.

Findings: Adolescent girls and boys undergoing treatment for obesity used visual-based social media, but girls in particular experienced weight stigma online and undertook self-presentation strategies to conceal weight-related content such as avoiding showing close-up photos of their bodies and not posting images of unhealthy “fattening” foods. Participants perceived the potential use of social media in clinical settings as being too risky and private.

Conclusions

Given the complexity of general visual-based social media use by adolescents, and not wanting their patient status to be visible to peers, healthcare should primarily focus on working with more restricted instant messaging when engaging with adolescents with obesity.

Keywords: Adolescence, digital media, Goffman, healthcare privacy, obesity, pediatrics, self-presentation, weight stigma

Introduction

The use of social media platforms among adolescents is extensive. In Sweden, 88% of girls and 70% of boys aged 13–16 use social media daily.1 Similar numbers have been reported in other high-income countries such as the United States.2 Snapchat and Instagram are currently the most popular social media applications, used by three out of four Swedish 13–16 year olds, with Facebook used by two out of four.3 Given the prevalence and impact of social media, it has been suggested that it is increasingly important to explore adolescents’ usage in relation to their health, and also explore how social media could be adopted in healthcare contexts.4–6 Health-related and clinical implications have been suggested including the need to better understand adolescent social media use to provide health information and promote health behavior change, to monitor online risk behaviors, and to enhance patient communication through such initiatives as clinic-specific social media groups.6,7

These ideas connect with current pediatric obesity treatments that display a move to patient-centered approaches.8 They highlight the growing need to enhance patient participation in treatment, and are an important prerequisite to better understanding patients’ subjective perspectives of their condition and treatments. However, much of the research on adolescents’ use of social media to date has viewed adolescents as passive and has often focused on the perceptions of parents or other adults.9 Little research has focused on adolescents’ own perspectives and experiences when it comes to their health in relation to social media.10

Moreover, several reviews have highlighted the complexity of using social media in a healthcare setting and suggest that more qualitative studies be performed to explore the conditions and implications for how social media can be used with adolescent patients. In their review of how social media is used for child health, Hamm et al.6 found that a majority of studies presented positive conclusions about the use of social media. However, they also report that many studies used platforms created by researchers themselves rather than widely available commercial platforms. They therefore suggest that research is needed to explore the use of the social media platforms that participants are already using. Similarly, Yonker et al.11 and Shaw et al.12 found that most studies concerning how social media is used for interacting with adolescents in order to achieve positive health outcomes had a narrow focus on online risk-behavior. They suggest that further studies on how best to incorporate social media into healthcare and health promotion are needed. The reviews conducted to date also highlight the need to develop further knowledge on sensitive issues around adolescents’ use of social media such as issues around privacy. Thus, in line with the reasoning articulated by Househ et al.,13 while research to date suggests that patients seem to have a positive view of using social media, critical issues concerning privacy and integrity need to be further explored.

Key amongst the conclusions of the reviews conducted to date is the notion that the use of social media in adolescence can be particularly sensitive. This conclusion is not entirely unexpected as the desire for peer approval intensifies during adolescence, and social norms about appearance and weight increase in importance.14 These social norms affect adolescents’ online communications and self-presentations.15 Many adolescents compare themselves with what peers reveal online, and a significant proportion report feeling worse about their lives as a result of what friends post on social media.16 A systematic review of quantitative research also indicates associations between the use of social networking sites and body image concerns among young individuals.17 Given that visual content is central to creating an online impression,18,19 research suggests that adolescents’ online profile photos tend to reproduce cultural and social norms as reinforced by mass media images, such as gender-specific beauty standards.20 Studies of visual presentation on social media platforms such as MySpace, chat sites, Twitter, blogs, and Facebook all reveal gender differences between boys who often present themselves as strong and girls who tend to present themselves as attractive and in a seductive manner.18 These visual presentation practices can be a sensitive issue for adolescents with obesity, particularly for girls whose bodies differ from prevailing thin beauty ideals in modern society. This makes the social media experiences of adolescents in treatment for obesity a particularly relevant concern.

Indeed, researchers have found that online social networks and communication platforms, Twitter, and Facebook often contain derogatory remarks pointing to weight stigmatization.21,22 Ultimately, this can lead to cyberbullying, which refers to harassment and bullying via digital channels.23 Research indicates that a majority of adolescents who seek weight-loss treatment have reported experiencing weight-based cyberbullying.24 This is serious as adolescents report that cyberbullying results in emotional distress, and that they feel more vulnerable when the bully is unknown, which is a common feature in cyberbullying.25

While a range of negative outcomes are possible, there are also positive aspects associated with using online social networks, such as enabling adolescents with obesity to find friends. The Pew Research Center16 reports that more than half of adolescents aged 13–17 have made a new friend online, and that a number have gone on to meet online friends in person. It can be challenging for adolescents with obesity to find friends, as demonstrated by Schaefer and Simpkins26 who found that non-overweight youth were significantly more likely to select a non-overweight friend than an overweight friend. Indeed, one of the key drivers for adolescents with obesity who seek treatment is a desire to socially integrate with peers and to avoid bullying.27 Online social networks can allow adolescents to find the support they may lack in offline relationships,7 particularly those who feel ostracized.28 Similarly, online social networks may also moderate weight stigma, and adolescents’ social networks may protect those with obesity from developing a poor body image29,30 while promoting health behavior changes such as weight-loss.7 Although such outcomes of social networking for adolescents with obesity are positive, they exist in concert with the range of negative outcomes that this vulnerable group may face. It is therefore important to unpack and better understand both sides of the experiences of these young people as they make use of online social networks.

Self-presentation online amidst weight stigma

One way to better understand adolescents’ experiences of using online social networks is to explore their perceptions around self-presentation on these platforms. Self-presentation is an important concept in human interaction and a key factor driving users of online social networks to reveal their personal information is the desire to maintain relationships.31 An established way to approach human interaction is to use the perspective of symbolic interactionism.32 Applying a symbolic interactionist approach to childhood obesity, we can draw on Goffman’s dramaturgical model33 to explore adolescents’ self-presentation on digital media.

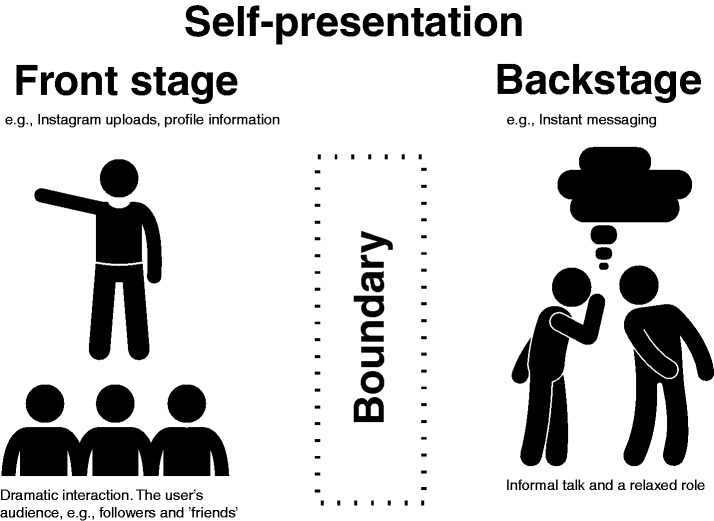

According to Goffman’s model, an impression is maintained at all times by the adolescents (or the actors, to use the terms of Goffman’s theatrical metaphor) while in front of their audiences. The boundaries between audiences and actors are defined as regions and these are divided mainly into areas of the front stage and backstage. Behavior on the front stage takes place before an audience, which, in social media terms, usually consists of a user’s followers and “friends.” Actors perform in such a way as to meet the social and normative expectations of behavior, the so called “dramatic interaction.” In this way, one of the most important factors for establishing a reliable impression is to avoid embarrassment. Please see Figure 1 for a visual depiction of Goffman’s33 model of self-presentation, adapted by Boyd34 for the interpretation of social media interactions.

Figure 1.

Illustration of Goffman’s model of self-presentation adapted to social media applications.

When actors are separated from their audience, during a pause from performing, they are considered to be in the backstage region. Following the theatrical metaphor, the boundary between front and backstage areas is controlled. Goffman explored this separation in relation to stigma, which he defined as an attribute which is socially discrediting.35 To fit in with a group, the stigmatized person can try to control what is shared when his or her stigma manifests itself, by maintaining a strict separation. She or he can also let a manifestation be visible in their front stage area, but manage any potentially negative reactions or consequences. In this way, individuals who possess stigmatizing traits such as obesity,36 typify the significance of impression management, which they navigate to alleviate social tensions caused by their stigma in order to interact comfortably with others.

Goffman’s account of social situations was developed with a focus on face-to-face interaction, but over the past two decades, the extension of Goffman’s model to mediated forms of interaction such as texting, chats, and social media has become well established.37,38 Boyd34 expanded the scope of Goffman’s theory of self-presentation33 to explore adolescents’ online interactions. She argues that what adolescents put forward online represents their best efforts in regard to what they want to say about who they are. In learning to make sense of others’ responses to their behavior, adolescents assess how well they have conveyed what they intended. This process of presentation, evaluation, and alteration is what Goffman33 referred to as impression management. Adolescents thus seek to define social situations by using contextual signals from the online environment in which they are engaged. Common signals such as friends in a network, hobbies, images, and an “about me” profile section all reveal something about the person that can be interpreted by others.39 Social networking sites contain a wealth of information including profiles, images, and posts that are often easily found.40 However, as with most social situations, it is difficult to control other users’ behaviors, and users must trust each other not to misuse information disclosed online.

This study draws on recent adaptations of Goffman’s theory of self-presentation for understanding online social network interactions, while returning to the kind of stigmatized group that was the focus of Goffman’s original works. The objective is to explore experiences of adolescents in treatment for obesity in terms of how they present themselves on social media, their rationale behind their presentations, and their feelings related to self-presentation.

Methods

In this study, an underlying assumption was that the adolescents’ experiences are constructed and contextual but that they also accommodate shared realities. Therefore, the study takes an interpretative approach and adopts a qualitative study design.41 To allow the adolescents who participated to share their experiences, individual interviews were used. During the interviews, participants had the opportunity to share their self-presentation practices on a laptop with Internet access, to assist in the interpretation of their experiences. Informed written and verbal consent was obtained from the participants and their parents. The study protocol was approved by the regional research ethics committee in Gothenburg (DNR: 035-15).

Participants

As previous research has shown that online self-presentation practices are partly dependent on an adolescent’s age as well as their gender,42 both male and female participants were chosen for inclusion from within a relatively narrow age range. Thus, all patients between the ages of 13 and 16 with an appointment at the pediatric obesity clinic at a Swedish university hospital received information and an invitation to participate in the study. This pediatric outpatient clinic specializes in moderate to severe obesity with significant metabolic comorbidities. It is a tertiary referral clinic that admits children who have been unsuccessful in losing weight under ordinary pediatric care.

During a two month period starting in spring 2015, a consecutive sample of adolescents visiting the clinic was invited to participate in the study. Parallel to the recruitment period, initial analysis of the interview material was conducted. This enabled the interviewer to adapt the interview questions based on previous interviews, and to determine when additional interviews did not result in any new information being added. The initial analysis indicated that a sample size of 20 would be adequate for theoretical saturation,43 such that several perspectives were represented in the data, and that new aspects were not raised during the final interviews. This sample size was met after 24 invitations.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews of 30–65 min duration were conducted in an interview room at the clinic. The interviews were conducted by the first author (CH) who is a registered nurse and PhD candidate. A female interviewer was also available if a gender preference was expressed by the participants, however participants did not avail themselves of this opportunity.

The interviews followed a thematic interview guide. In line with recommendations from Hsieh and Shannon,44 initial open-ended questions were used to obtain a broad understanding of the adolescents’ social media practices and experiences. An image sheet depicting different social media applications was used as stimulus for the interviews. This enabled the interviewer to center the interview questions on the social media applications the participants were using.

Thereafter, questions were asked related to the adolescents’ experiences of self-presentation on social media. These interview questions focused on aspects of self-presentation that are under the adolescents’ control and were informed by previous qualitative research on adolescents’ and young adults’ self-presentation on social media,42,45 The questions examined what online profile attributes the adolescents chose to complete and what type of images and updates they posted and shared with others. Conceptually, self-presentation was understood through Goffman’s33 and Boyd and Marwick’s46 definitions of self-presentation as expressions and appearances that we “give” to others. Thus, participants were asked how and why they presented themselves to others online, what they chose not to show or share with others online, and what they considered and highlighted in their self-presentations.

Boyd and Marwick46 argued that adolescents’ self-presentations in networked public spaces are shaped by factors such as the adolescents’ understanding of their social environment and their technical abilities. To capture these dimensions, the participants were also asked about their interpretations of social situations when they presented themselves, their attitudes toward privacy and publicity, and how they perceived their ability to navigate the technical and social environment online. Questions reflecting these aspects included “Why did you choose that profile picture?”; “How did people in your online network react to your image?”; “Did you tell anyone on social media about your visit to the obesity clinic today?”; and “What do you feel is too private to show to others in your online network?” Since the adolescents’ feelings and reasoning were central to the focus of the study, follow-up questions were then posed, such as “What did you think then?”; and “How did that make you feel?”

During the interviews, participants used a laptop to share examples of their self-presentation practices. In doing so, the interviews could be centered on concrete presentation practices that the adolescents engaged in and on their experiences and feelings about these practices. Of the 20 participants, 19 agreed to share their self-presentation practices using the interview laptop. The interviews were audio recorded, and screen activities were captured using the software Camtasia Studio 8.5 (TechSmith). This enabled the first author, who conducted the interviews, to share self-presentation practices and online examples with the rest of the research group during the analysis.

Analysis

The interview material was transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a directed approach to qualitative content analysis described by Hsieh and Shannon.47 Goffman’s dramaturgical action model was used as a theoretical framework, and categories and subcategories were labeled and organized according to the concepts of front stage and backstage. For example, some participants mentioned that they concealed aspects such as their weight when they presented themselves to others online. This was thus categorized using Goffman’s notion of a front stage area, as it pertains to what individuals consider when they present themselves to others publicly (their audience). Another example was that some participants described how they could discuss their health or clinic visits with certain trusted friends online but that they did not want to disclose this to all of their followers/friends. This was thus categorized using Goffman’s notion of a backstage area.

Data were explored in the following ways: 1) the interviews were listened to several times to appreciate the nuances and ambiguities, and the transcribed text was read several times to fully understand the material; and 2) as the goal of the analysis was to categorize and identify all instances of the adolescents’ self-presentation activity, all text segments relating to the study aim were highlighted and thereafter labeled with codes. Similar codes were ordered into tentative categories that shared a commonality. Although the analysis is depicted as a linear process, the actual analytical procedure was performed back-and-forth, and the codes and related text segments were repeatedly discussed in relation to the tentative categories by three of the authors (CH, CB, and JC). During this process, the laptop screen recordings assisted by demonstrating contextual materials such as the participants’ use of digital image-manipulation techniques, the variations in presentation modalities (images, video, and text), the possibility to identify patterns by comparing older and more recent postings, and their reactions to postings from friends and followers. Analytical discussions considered each code as a potential explanation for the statements made, while seeking to find the simplest and most likely explanation using the collected details of participant utterances and activity.

The resulting categories are mutually exclusive, such that each code can only be assigned to one category. See Table 1 for an example of the categorization procedure.

Table 1.

Illustration of the categorization procedure

| Text segments from the interview transcripts | Codes | Category |

|---|---|---|

| P: I don’t get why people join online groups about food and health. I do not want to show those things to others, if I want to lose weight then why would I join online groups or get tips like that online. I don’t want that, because then everyone can see that I have been doing that and ’liked’ that content and stuff. | Not wanting to disclose health content to others | Keeping health backstage |

| P: I have not told any of my friends, and I have been going here (obesity clinic) for almost a year. So, I feel that it is very sensitive. I don’t even want to tell my brother. I: So that is something we would have to consider if we use social media here at the clinic? P: I mean, it is ok if people know about it, but it is embarrassing, I think it is difficult with social media here, because one does not want others to find out about it. | Embarrassing and private to disclose clinic visits | |

| P: If I share a photo of me and a friend, that is a private image, but if I share an image of when I am here at the hospital, that is something else, if it is about the hospital, then it only concerns me and my family, it is something extremely, extremely private. | Too private to share clinic visits |

P = participant, I = interviewer

Following Creswell and Miller’s48 recommendations, the credibility of the analysis was checked through a process of discussing the findings and analytic process with personnel at the obesity clinic. However, this discussion did not result in revisions of the category scheme but rather confirmed the findings. Study findings were summarized and sent by email to the study participants to enable them to comment on the results, though none chose to.

Findings

Interviews were conducted with 11 girls and 9 boys, aged 13–16 (median = 15), who had been enrolled at the obesity clinic for between 3 and 98 months (median = 25 months). According to age- and sex-specific body mass indices,49 11 participants were classified as having morbid obesity, 8 as having obesity, and 1 as being overweight. Although some of the participants had foreign backgrounds (e.g., one or two parents born outside of Sweden), all of the adolescents spoke Swedish.

All of the participants used social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, and the majority also used instant messaging applications such as Snapchat. This sample’s use of social media was similar to patterns of use reported in national statistics for this age group.3 See Table 3 for a list of commonly used social media services that the participants used.

Table 3.

Examples of social media used by the participants

| Participant | Services | Social networking sites (e.g., Instagram, Facebook) | Chat applications (e.g., Snapchat, KiK) | Media-sharing sites (e.g., YouTube) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | x | x | ||

| 2 | x | |||

| 3 | x | x | x | |

| 4 | x | x | x | |

| 5 | x | x | x | |

| 6 | x | x | x | |

| 7 | x | x | ||

| 8 | x | x | ||

| 9 | x | x | ||

| 10 | x | |||

| 11 | x | x | x | |

| 12 | x | x | x | |

| 13 | x | x | x | |

| 14 | x | x | x | |

| 15 | x | x | x | |

| 16 | x | x | x | |

| 17 | x | x | x | |

| 18 | x | x | ||

| 19 | x | x | x | |

| 20 | x | x | x |

Based on the adolescents’ descriptions of their experiences, we generated three main categories and five subcategories regarding how the adolescents presented themselves, their rationale for their presentations, and their related feelings. The categories were then considered in relation to Goffman’s notion of backstage and front stage areas, and in relation to the adolescents’ reported experiences of social recognition, integrity, and risk-reduction online. See Table 2 for a list of the categories.

Table 2.

Illustration of categories and subcategories

|

|

|

When quoted material is presented, “P” stands for participant, “I” for interviewer, “#/M” is for males’ ages in years, and “#/F” for females’ ages.

I. Creating a safe and purposeful stage

The first category reflects the adolescents’ descriptions of how and why they selected certain social media platforms when engaging with others online. They expressed a number of reasons such as avoiding platforms that they perceived as enabling hateful communication and interaction, practical decisions such as the selection of applications that best complied with the type of content they wanted to share, and control and management of perceived risks. Participants expressed general concerns that, compared with their peers of normal weight, their excess weight put them at greater risk of receiving unkind comments online. The adolescents also described using general risk-reduction practices to prevent wrongful use of their personal information as well as to protect their privacy. Furthermore, they mentioned that they had different followers and networks on different platforms, such as separating between family members and friends, or having different kinds of friend groups on different platforms.

Ia. Avoiding platforms that enable unkind comments

The adolescents described that they avoided platforms that, in their experience, enabled unkind communication such as bullying and hateful communication. The participants emphasized that certain applications, such as ASKfm, facilitated more hateful communication than others, in that users negatively commented on images, and abusive name-calling was used. In particular, the adolescents perceived that anonymity features allowed more hateful communication to take place. This experience could also occur on more common services as one girl’s experience of hateful communication on Facebook illustrates:

There is a lot of hate, there is so much hate on Facebook. You see people hating each other a lot on Facebook. No, it is not for me … people comment really mean on images, I want to stay away from that (15/F).

Despite witnessing such communications, the adolescents did not always delete their accounts on the more popular platforms but did say that they visited them less often. They said they kept the accounts because they had certain friends or family members on those platforms and wanted to stay in contact with them. The adolescents also said that their friends warned them to stay away from certain platforms and that they took such advice seriously. They believed that their friends had their best interests at heart, which indicates a kind of social support as described by the participants.

Ib. Selecting platform according to what one wants to present

The adolescents also said that the content they wished to share influenced which digital media they preferred to use. The participants described, for example, that they used Instagram to display significant and special events that they intended to save for a longer period of time. By contrast, instant messaging apps such as KiK or the photo-sharing platform Snapchat, where images are deleted after viewing, were used for connection and to share everyday events of less significance. These apps were also used to communicate private matters that they did not want everyone in their network to know about. Thus, the adolescents talked about choosing platforms based not only on their intended audience but also on the type of content and intended use:

I update Snapchat all the time, I am doing this now, walking and stuff, smaller stuff, I share things everyday on Snapchat. Instagram contains images that are more important like a party or holiday (13/F).

Thus, the adolescents described that the temporary nature of certain applications such as Snapchat seemed to align with, and encourage, frivolity and emphasized another kind of everyday flow of interaction and events, compared with more permanent platforms such as Instagram.

Ic. Managing and probing one’s audience

The adolescents said they avoided interacting with unknown users or users they did not know well, as doing so made them feel uncomfortable and unsafe. They considered less-known users as outsiders, and they did not want them to have access to their information. In general, the participants avoided sharing information they considered too personal or private, as it might be used in a negative or destructive way by others, and they avoided unwanted connections in their networks. They explained, and gave several examples, that this awareness usually stemmed from previous mistakes from which they had learned, such as replying to an anonymous profile that then began to engage in unsolicited and sexually explicit communications. One girl was particularly aware of the potential risks if her images were to end up with the wrong person:

but also to screenshot the image, then they can edit it, post it on porn sites, videos, and everything and then, all of a sudden, you lose control over the image. So you have to be careful with that, to think about who you are sending things to (14/F).

The adolescents seemingly demonstrated a high sense of risk-based thinking and awareness of potential online threats. They provided several examples of situations where they had received unkind comments, such as being teased about their weight, and believed that it was more likely that they would receive these comments from people they did not know or from anonymous users. One participant who had posted several photos of himself on his Facebook profile described feeling comfortable presenting images of his body and weight because he knew all his friends on Facebook in person and, therefore, believed that they would not post unkind or cruel comments.

I: Like here, on Facebook (pointing at the screen), you share images of yourself. Considering that you have a larger body size, do you think that it influences how you present yourself online?

P: No, people there on Facebook know who I am, and they have nothing against me, so it has not affected how I present myself, I have not received mean comments or anything (16/M).

The adolescents generally described risky situations as something they always had in the back of their minds when they were online, which made them more careful about the users they interacted with and kept them on guard. Some participants also expressed appreciation that they could talk to their parents about risky and uneasy situations online, which created a sense of comfort.

II. A special, admirable, and modifiable front stage

This category referred to the adolescents’ descriptions of what they considered in their self-presentations to others and the various strategies they used to convey themselves according to their own and others’ expectations. This concerned both manifest elements such as what image motifs they selected, but also underlying motives including what they wanted to signal such as social identity and confidence. The adolescents described how they presented themselves, reflecting their bodily appearance, but also symbols and elements such as background elements and settings. The adolescents described that they were familiar with using photo editing tools and different ways to manipulate one’s appearance online. One girl noted, “You can be someone else online, and no one knows who you are, you can hide behind the screen” (14/F).

However, the participants generally said that they did not depict themselves as someone completely different online but rather, they modified certain aspects of themselves by emphasizing particular elements while hiding others.

IIa. Presenting what is important to oneself and expected from others

The participants said they wanted to share content they felt was important and special to them. An occasion could be special if it was something memorable; since it was meaningful to them, the adolescents wanted to remember it longer. Participants also mentioned that something could be special to them if it was rare, such as a restaurant outing, a party, or another occasion they experienced only rarely. The adolescents also described that what they perceived as meaningful was presented and shared with their entire audience, while more everyday and mundane activities would be presented and shared with a selected few. At the same time, the adolescents also said that they wanted to generate the admiration of others, and that this was generally driven by acquiring social status, exemplified by one participant: “one really wants to brag and show pretty and cool stuff to impress others” (16/M). The adolescents gave examples such as presenting themselves as popular by showing social situations with friends, situations, or objects that others considered “cool” and desirable events and items.

The adolescents were also concerned about presenting themselves as well-liked; for example, one girl said she strived to get as many “likes” as possible with her Instagram images and removed images that did not get many likes. Participants used props and symbols, such as displaying items from expensive food-related brands when eating out, for example. The adolescents described knowing that these products and brands had positive associations among their peers, which signified social status that could generate likes and positive comments. One girl talked about this in relation to sharing images from the American coffee chain Starbucks: “even if one has never had a Starbucks beverage or visited the place, one still loves it, because one knows that everyone else loves it” (14/F).

Gender differences were apparent regarding how participants presented their bodies and weight. Most boys said they were comfortable showing themselves and presenting their appearance, such as images of themselves, online. Reasons they gave were that they adopted strict privacy settings or simply did not consider their obesity to be an issue. The girls, however, acknowledged pervasive appearance norms but said they did not always comply with them. One participant said she could post images of her body online because she has good self-esteem. Another reason was that they valued their own opinions above those of others: “if I think it is pretty or looks good, then I do not care about others. I am more like that, they can think whatever they want, but it is my opinion that matters the most” (15/F).

The participants thus demonstrated a certain level of empowerment, as they were aware of appearance norms and bullying against overweight and obese individuals, but they felt secure about presenting themselves online because they had created a safe arena and they tried to ignore other people’s expectations by following their own convictions.

IIb. Enhancing one’s manner and masking one’s weight

Participants explained that they often aimed to improve certain aspects of their offline selves online rather than presenting themselves as someone completely different. This behavior was usually described as displaying a more favorable image of oneself by highlighting content associated with social status or by concealing part of themselves such as their weight. The participants stressed that the images still needed to be realistic and not too exaggerated, as well as the need to find a balance between positive enhancement and what they perceived to be plausibly authentic to present to others.

Participants described that, online, they could portray themselves as someone more confident and have that impression believed by their audience. This indicates that they modified the manner in which they presented themselves to produce accounts of themselves they perceived to be more favorable, successful, and self-assured. Yet, while balancing the situational authenticity, these accounts needed to be received as genuine. Such active impression management is illustrated by one participant:

Well, if I post images with luxurious food and clothes and things like that, then they will believe it is mine, if my images are realistic enough. If I do that they will believe that it is my life and that I am on top, but really, I am a depressed teenage girl who sits in my room and listens to Justin Bieber (14/F).

The adolescents also said that they did not want to be judged based on their weight, although a gender difference was apparent in this category. Girls often described modifying their presentations in ways in order to appear thinner online. These participants mentioned being afraid of being bullied if they presented their actual bodies to others online, and some had experienced the online environment as unsafe for larger girls:

I posted an image on Instagram once, and I did not think about how people would react, and then someone said that I looked fat which was difficult. … There are not that many images of big people. So you never see any big persons pose as a fit person does, you never see that because you are scared to get bullied and get mean comments and that is not safe. It feels like an unsafe environment (16/F).

Participants said they felt pressured to match their self-presentation with audience expectations and preferences. This was described as a process whereby they learned from previous situations of others’ reactions, which caused them to adapt their own self-presentation practices. Participants expressed perceiving a particular focus on appearance online and that they experienced social media as a shallow environment due to their peers’ focus on visual presentation. As a result, they reported considering the potential consequences and repercussions before posting images of themselves. The focus on appearance online is distinctly illustrated by one girl:

P: It is very much pressure, at least I think so, that it is very much pressure.

I: How does that make you feel?

P: It feels like kind of bad that it is so much focus on that, that one cannot post, that one cannot post the wrong image. You always have to post the prettiest one (14/F).

Similarly, other girls expressed that they modified images of themselves in order to appear slimmer and undertook certain self-presentation strategies so that their weight would not be in focus:

when I take a photo of myself, I think about how I dress, how the light and shade is, how the hair lays, how the eyebrows are fixed, so that the face looks skinnier, and stuff like that. … I don’t want people to see images of me and think that “she is so big” or “she is fat” and stuff like that. No one thinks that is nice (14/F).

Participants said that they protected themselves and their self-esteem by not disclosing their weight, as this minimized the risk of receiving potentially hurtful comments. This was related not only to the presentation of their bodies but also to posting motifs more broadly associated with weight, such as certain foods: If I eat something unhealthy, I do not want to post images of that since I can be judged, and people who will see that, they will think that I am big because of it (13/F).

These statements illustrate a category that highlights ways in which participants edit or mask their obesity and things and situations associated with their weight to avoid bullying and unkind comments that many had observed and some had experienced. While some girls mentioned outright bullying, they also said that posting images of their bodies could result in “drama.” The adolescents expressed that images of their bodies and information about their weight would cause drama and unwanted attention. In response, concealing their weight was a way to protect themselves and their self-confidence.

Therefore, the participants presented partly edited versions of themselves where they could focus on certain aspects of their personality and physical appearance but choose not to disclose their weight. These practices were experienced as positive in that they allowed them to have control over their presentations. But participants also described it as exhausting, as they felt that they had to work to manage their presentations in order to comply with their followers’ expectations.

III. Keeping health backstage

This third category reflected participants’ experiences of being cautious about disclosing information relating to their health and healthcare, such as weight-loss activities they undertook or visits to the obesity clinic. They saw this information as private, as it could raise questions from others and cause them embarrassment.

The participants generally wanted to keep these activities to themselves and not share them with others. One girl said she did not want to visit weight-loss sites such as Weight Watchers via social media as this could be disclosed to her friends. Participants were also concerned about their visits to the obesity clinic; visits and treatments were regarded as particularly private. When asked if social media could be used by the clinic to interact with adolescent patients, the participants said they thought it would be too private and that not many would join:

When you are overweight, you do not want anyone to know that you visit the hospital. People would start talking about it. I would not like it if others knew that I was here. There would be too much drama (13/F).

This participant and several others mentioned that posting or sharing their healthcare visits would again result in unwanted drama. However, the drama associated with this type of self-disclosure was described in different terms from the drama mentioned by the female participants when showing their bodies or weight. Disclosing their visits to the clinic would attract unwanted attention but in the form of caring and considerate recognition. The participants expressed that they did not want people around them to worry about them or make their patient status an issue. The participants added that visiting the obesity clinic concerned only themselves and their families. Some even said they did not mention the clinic to certain family members. One participant said:

I have not told anyone, it is something private, I post private things on Facebook, but this, it is very private. You should not post private, very special things on Facebook in my opinion. … If I share a photo of me and a friend, that is a private image, but if I share an image of when I am here at the hospital, that is something else, if it is about the hospital, then it only concerns me and my family, it is something extremely, extremely private (16/M).

However, one participant did share images of the obesity clinic visit to a special friend through an instant messaging app. When asked about this, she said she wanted her close friend’s support, “because I feel that, if people know this, then they can help me, and remind me to, like ‘do not eat this’ or ‘do not take so much of that’ or things like that, because then they can help me” (14/F).

Thus, presenting themselves online as patients was a complex matter. When it came to their health and healthcare status, participants mostly kept it to themselves or confided in only a selected few through direct messaging and not sharing such information with everyone in their networks.

Discussion

The results in this study indicate that participants had broadly similar experiences online to adolescents without obesity, including the practices of highlighting socially desirable events, avoiding negative interactions, and modifying images of themselves in ways that complied with audience expectations (cf. Boyd15). However, the study contributes by positioning such experiences with regard to adolescents with obesity who deal with issues related to their weight status, body image, and health concerns. The analysis of experiences described by study participants also offers valuable insights into the particulars of the social media experiences of this patient group and raises relevant clinical considerations.

The first main category, creating a safe and purposeful stage, has several connections with previous studies. These practices described by the participants align with what Goffman33 defined as audience segregation, such that specific performances were shared with specific audiences. Thus one interpretation, mirroring findings by Livingstone,50 could be that the adolescents arranged a front stage area for the expectations of each audience according to the specifics of each social media platform and/or group. In this way, they oriented to differing potentials for negative interactions that different platform features such as anonymity51 occasion.

The second category, a special, admirable, and modifiable front stage, also relates to Goffman’s33 concept of impression management. In contrast to other populations of social media users, such as those who use the popular #fitspiration hashtag to identify posts where they present a physically fit identity,52 the adolescents in the present study were more explicitly selective and cautious when presenting their bodies. In relation to this theme, a gender difference was also noticeable. Female participants, in particular, emphasized a focus on looks and on appearing slim online, a feature also reported in other studies.18 These findings can be understood in light of the different appearance norms that are prevalent for girls and boys.20,53 While prevailing norms are that girls should generally look thin and pretty, it is more socially acceptable for boys to appear as big and strong.42 These findings might also indicate that social media are not as emancipatory in terms of individual reinvention as has often been suggested,20 but rather that adolescents are subject to similar strict appearance norms and beauty ideals as elsewhere in society.

The final category, keeping health backstage, connects in several ways with previous studies on healthcare privacy. Specifically, the participants’ views regarding privacy differed from those reported in other studies. Cheung et al.54 found that the perceived privacy risk did not have any impact on self-disclosure in social networking sites among adults. In our study, however, the participants were aware of privacy risks associated with social networking sites and reported that this awareness did affect their self-presentation, especially with regard to their patient status and to their unwillingness to share healthcare information. Research with adolescents both with and without chronic illnesses consistently shows that adolescent patients value privacy in the healthcare setting.55 For the participants in our study, this indicates that social media was a place to be a “regular” rather than an obese and “sick” teenager. Thus, to some extent, online networks permit young patients to escape their patient status and be ordinary teenagers.

Cyberbuylling and “drama” from adolescent patients’ perspectives

The findings in this study suggest a change in how clinicians orient to patient talk about bullying and particularly cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is widely discussed in the literature around adolescents’ use of social media.23,56 The findings suggest that cyberbullying is not always a relevant category for adolescents to describe social conflicts online and that clinicans thus need to understand other closely aligned concepts such as “drama” to fully grasp adolescents’ experiences of online conflicts.

For example, when the girls expressed that they had experienced derogatory comments in response to occasions when they had revealed their bodies and weight, they often described and labeled this dynamic as gossip or drama rather than as bullying. The participants’ talked about this interaction in terms similar to what Marwick and Boyd57 reported: that when adolescents interact in social networks, they need to negotiate an ecosystem in which their peers are not only socializing but also competing for social status. With these dynamics, obesity and excess weight are not associated with elevated social status, quite the contrary. However, derogatory comments and gossip about weight may not always be identified as bullying, as cyberbullying and indeed bullying itself may not be relevant categories for the adolescents to describe their experiences. Researchers have reported that adolescents view the victim’s experience of hurt and harm as a central component for defining bullying and not merely a result of bullying.58

One possible explanation to why the adolescents label unkind comments as drama instead of bullying is that it might enable them to define their own engagement with social conflicts in ways that differ from the typical bully–victim dynamic, which is often established by adults. The limited research on drama suggests that, unlike bullying, drama is viewed by adolescents as bidirectional, such that incidents do not necessarily involve a victim being targeted and exposed to negative actions by a perpetrator. Thus, it may be useful to talk about the issues as drama when talking to adolescents. They may feel more comfortable using this term than to admit to being bullied.

There is a need to better understand adolescents’ concept of drama because a narrow focus on bullying may ignore the very real hurt it causes. In this study, the adolescents described varying events and situations that created drama and different experiences of the relationship between drama and bullying. It is thus important to focus on the individual’s own and unique experience of drama, as the level of engagement and negative consequences associated with drama is individual.

Clinical considerations

Researchers have suggested that social media could be applied in the healthcare and in health interventions targeting adolescents.59 Such uses could be to help treatment-seeking adolescents to interact with other adolescents with obesity for social support such as sharing diet tips and treatment results.7 For such purposes, reviews suggest that it might be preferable to use social media platforms that adolescents are already using instead of creating clinic-specific platforms.6 If so, the unwanted aspects that the participants in this study described need to be considered so that the feasibility of using social media in a pediatric clinic can be evaluated.

First, issues related to healthcare privacy need to be considered. The participants in our study emphasized that they would consider it too sensitive an issue for their clinic to intervene in their social media lives by, for example, hosting a discussion group on Facebook, due to what Marwick and Boyd60 describe as context collapse. Context collapse refers to the way that social media collapses distinct audiences, often breaking down boundaries that exist between the distinct offline community spheres that people participate in. Thus, if a social media group is used in the clinic, it is important that the adolescents have the ability to segregate their audiences, for instance by making the group private and invisible to the adolescents’ peers. It is also important to address anonymity issues, which the participants raised as a concern. This implies inviting the adolescents to join the group via the clinic with membership restricted to interested adolescents that are attending the clinic. In this way, the clinic acts as a “gatekeeper” to the social media group, safeguarding the integrity of its members.

Second, it is important to consider the method of interaction, the information content, and the group dynamics of the group. For example, while studies contend that video-based social media can have more of an impact on patient engagement than text-based interventions,13 it is important to be attentive to potential drawbacks; for example, visual media might be especially sensitive for adolescents who feel stigmatized about showing their bodies.

Third, it may also be important to let the purpose of the group guide which social media platform is used. Social media platforms offer many features that allow adolescents to present edited and idealized versions of themselves. Those in our study mentioned that they were more attentive and presented themselves in a more idealized way on Instagram, for example, than they do on other platforms such as those based on instant messaging such as Snapchat where they described revealing more realistic and authentic images of themselves to a selected few. For example, Instagram could be used as weight-loss inspiration providing images and videos of treatment results and healthy recipes, while the instant messaging options could be used to provide personal feedback.

Strengths and limitations

The interview situations for this study can be understood as situations in which participants engage in impression management. While we interviewed the adolescents in this study at only one time point, all but one participant did let us view their social media profiles, providing us with contextual material to consider in relation to the interview statements they made. This also made it possible to get an overview of their presentations from different time points, from more recent to older posts. Additionally, it allowed us to identify recurring content or designs in their presentations that the adolescents were not always aware of, which assisted us in formulating relevant and participant-specific questions during the interviews.

Based on interviews, this study returns to the origins of Goffman’s theory of self-presentation through an interest in individuals living with stigmatized traits while examining different aspects of his framework in relation to the relatively new process of creating online identities. The various cases explored here indicate that Goffman’s theory has use as an explanatory framework for understanding adolescents’ self-presentation online.

Adolescents’ experiences of obesity and self-presentation are dependent on context, with stigmatization potentially less severe when being overweight is the norm. As childhood obesity is still less common in Sweden than in many other high-income countries,61 study participants might have experienced more stigma or a stronger sense of isolation than in settings where obesity is more common. Therefore, caution is needed when transferring these study findings to other settings. Latner and Stunkard62 however, showed that adolescents with obesity in the United States are similarly stigmatized after the obesity epidemic, compared with before, so how strong this mechanism is remains unclear. Furthermore, the study findings should be viewed with caution in terms of their transferability. The adolescents were all recruited from university hospital referrals, meaning that they can be considered to be severe cases. Thus, study findings might not reflect the experiences of adolescents with obesity in the general population.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that adolescents in treatment for obesity, and girls in particular, experience weight stigma online and, thereby, undertake a range of self-presentation strategies to conceal and modify their bodies and their weight. Moreover, while some adolescents described instances and situations that resemble cyberbullying, most described receiving negative comments and gossip in terms of drama. Because cyberbullying may not be a relevant category for the adolescents to describe their negative experiences, we need to understand adolescents’ experiences of drama to not miss what they experience as destructive online interaction. A too-strict focus on bullying may ignore the distress caused by a range of related social behaviors online.

The adolescents were generally not keen to reveal their health status to others in social media and thus believed that using social media in a clinical setting might be problematic. Healthcare personnel need to understand impression management in social media as an important practice for adolescents in obesity treatment, specifically, that online performances are not always intended to accurately reflect lived experiences offline. Instead, taken as the product of extensive impression management efforts, the online performances of adolescents with obesity offer insights into the ways they perceive themselves and others, in addition to their challenges and aspirations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and their families.

Contributorship

CH, CB, TH and JC designed the study. CH conducted the interviews. CH, CB, and JC conducted the data analyses. CH wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The regional research ethics committee in Gothenburg approved the study protocol (DNR: 035-15).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Formas, the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, (grant # 259-2012-38), and is a research activity within EpiLife, Gothenburg’s center for epidemiologic studies (Forte 2006-1506).

Guarantor

CH

Peer review

This manuscript was reviewed by three individuals who have chosen to remain anonymous.

References

- 1.Alexandersson K, Davidsson P. Eleverna och Internet 2016 Svenska skolungdomars internetvanor [The students and the Internet 2016. The Internet habits of Swedish students]. Stockholm: IIS (Internetstiftelsen i Sverige), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenhart A. and Pew Research Center. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015, http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/ (2015, accessed 5 May 2017).

- 3.Swedish Media Council. Ungar & medier, 2017 [Youth & media, 2017], https://statensmedierad.se/download/18.7b0391dc15c38ffbccd9a238/1496243409783/Ungar%20och%20medier%202017.pdf (2017, accessed 10 August 2017).

- 4.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC . The health communicator’s social media toolkit, http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/ToolsTemplates/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf (2011, accessed February 10 2015).

- 5.Eckler P, Worsowicz G, Rayburn JW. Social media and health care: An overview. PM&R 2010; 2: 1046–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamm MP, Shulhan J, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the use and effectiveness of social media in child health. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmberg C, Berg C, Dahlgren J, et al. Health literacy in a complex digital media landscape: pediatric obesity patients’ experiences with online weight, food, and health information. Health Informatics J 2018; DOI: 10.1177/1460458218759699. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cheng JK, Cox JE, Taveras EM. Patient-centered approaches to childhood obesity care. Child Obes 2013; 9: 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James C. Disconnected: youth, new media, and the ethics gap. UK, London: MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausmann JS, Touloumtzis C, White MT, et al. Adolescent and young adult use of social media for health and its implications. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2017; 60: 714–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yonker LM, Zan S, Scirica VC, et al. “Friending” teens: systematic review of social media in adolescent and young adult health care. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw JM, Mitchell CA, Welch AJ, et al. Social media used as a health intervention in adolescent health: a systematic review of the literature. Digital Health 2015; 1: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Househ M, Borycki E, Kushniruk A. Empowering patients through social media: the benefits and challenges. Health Informatics J 2014; 20: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voelker DK, Reel JJ, Greenleaf C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adoles Health Med Ther 2015; 6: 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd D. It's complicated: the social lives of networked teens. New Haven, Conneticut, USA: Yale University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenhart A, Smith A, Anderson M, et al. Teens, technology and friendships: video games, social media and mobile phones play an integral role in how teens meet and interact with friends, http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/08/Teens-and-Friendships-FINAL2.pdf (2015, accessed August 10 2015).

- 17.Holland G, Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016; 17: 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herring S, Kapidzic S. Teens, gender, and self-presentation in social media. International encyclopedia of social and behavioral sciences. Oxford: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd D, Heer J. Profiles as conversation: networked identity performance on Friendster. In: Proceedings of the Hawai’i International Conference on System Science (HICSS-39), Kauai, Hawaii, USA, 4–7 January 2006, Vol. 3, pp. 59c-59c. IEEE. DOI: 10.1109/HICSS.2006.394

- 20.Kapidzic S, Herring S. Race, gender, and self-presentation in teen profile photographs. New Media Soc 2015; 17: 958–976. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Brun A, McCarthy M, McKenzie K, et al. Weight stigma and narrative resistance evident in online discussions of obesity. Appetite 2014; 72: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou WY, Prestin A, Kunath S. Obesity in social media: a mixed methods analysis. Transl Behav Med 2014; 4: 314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nocentini A, Calmaestra J, Schultze-Krumbholz A, et al. Cyberbullying: labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Aust J Guid Couns 2010; 20: 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Weight-based victimization: bullying experiences of weight loss treatment-seeking youth. Pediatrics 2013; 131: e1–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider SK, O’Donnell L, Stueve A, et al. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: a regional census of high school students. Am J Public Health 2012; 102: 171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer DR, Simpkins SD. Using social network analysis to clarify the role of obesity in selection of adolescent friends. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: 1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reece LJ, Bissell P, Copeland RJ. ‘I just don't want to get bullied anymore, then I can lead a normal life’; Insights into life as an obese adolescent and their views on obesity treatment. Health Expect 2016; 19: 897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritz GK. Social media use and adolescents: a guide for parents. The Brown University CABL 2014; 30: I–II. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farhat T. Stigma, obesity and adolescent risk behaviors: current research and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol 2015; 5: 56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caccavale LJ, Farhat T, Iannotti RJ. Social engagement in adolescence moderates the association between weight status and body image. Body Image 2012; 9: 221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krasnova H, Spiekermann S, Koroleva K, et al. Online social networks: why we disclose. J Inf Technol 2010; 25: 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd D. Why youth (heart) social network sites: the role of networked publics in teenage social life In: D Buckingham. (ed) MacArthur Foundation series on digital learning: youth, identity, and digital media volume. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007, pp. 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goffman E. Stimga: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall Inc, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomiyama AJ. Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite 2014; 82: 8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murthy D. Towards a sociological understanding of social media: theorizing Twitter. Sociology 2012; 46: 1059–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knorr-Cetina K. The synthetic situation: interactionism for a global world. Symb Interact 2009; 32: 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Counts S, Stecher K. Self-presentation of personality during online profile creation. In: Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, San Jose, California, May 17-20, 2009. pp. 119–142. Menlo Park, California: The AAAI Press.

- 40.Awan F, Gauntlett D. Young people’s uses and understandings of online social networks in their everyday lives. Young 2013; 21: 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y-Y, Shek Daniel TL, Bu F-F. Applications of interpretive and constructionist research methods in adolescent research: philosophy, principles and examples. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011; 23(2): 129–39 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Swedish Media Council. Duckface/stoneface – sociala medier, onlinespel och bildkommunikation bland killar och tjejer i årskurs 4 och 7 [Eng. social media, online gaming, and visual communication among boys and girls in grade 4 and 7]. Stockholm: Swedish Media Council, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. London, UK: SAGE publications Inc, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manago AM, Graham MB, Greenfield PM, et al. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J Appl Dev Psychol 2008; 29: 446–458. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyd D, Marwick A. Social privacy in networked publics: teens’ attitudes, practices, and strategies. Oxford, UK: Oxford Internet Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsieh FH, Shannon ES. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creswell J, Miller D. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract 2000; 39: 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012; 7: 284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livingstone S. Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media Soc 2008; 10: 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santana AD. Virtuous or vitriolic. Journalism Pract 2014; 8: 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. ‘Strong is the new skinny’: a content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. J Health Psychol 2018 Jul; 23(8): 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang-Péronard JL, Heitmann BL. Stigmatization of obese children and adolescents, the importance of gender. Obesity Rev 2008; 9: 522–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung C, Lee ZWY, Chan TKH. Self-disclosure in social networking sites: the role of perceived cost, perceived benefits and social influence. Internet Res 2015; 25: 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Britto MT, Tivorsak TL, Slap GB. Adolescents’ needs for health care privacy. Pediatrics 2010; 126: e1469–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beckman L. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying among Swedish adolescents: Gender differences and associations with mental health. Karlstad, Sweden: Karlstads universitet, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marwick A, Boyd D. ‘It’s just drama’: teen perspectives on conflict and aggression in a networked era. JYS 2014; 17: 1187–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hellström L, Persson L, Hagquist C. Understanding and defining bullying – adolescents’ own views. Arch Public Health 2015; 73: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balatsoukas P, Kennedy CM, Buchan I, et al. The role of social network technologies in online health promotion: a narrative review of theoretical and empirical factors influencing intervention effectiveness. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marwick A, Boyd D. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media Soc 2011; 13: 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. Worldwide trends in body mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017; 390: 2627–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latner JD, Stunkard AJ. Getting worse: the stigmatization of obese children. Obesity Res 2003; 11: 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]