Abstract

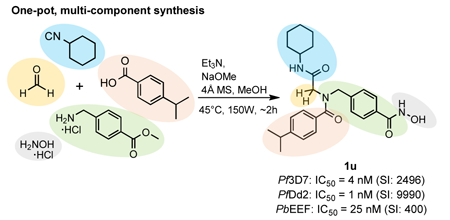

Malaria drug discovery has shifted from a focus on targeting asexual blood stage parasites, to the development of drugs that can also target exo-erythrocytic forms and/or gametocytes in order to prevent malaria and/or parasite transmission. In this work, we aimed to develop parasite- selective histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) with activity against the disease-causing asexual blood stages of Plasmodium malaria parasites as well as with causal prophylactic and/or transmission blocking properties. An optimized one-pot, multi-component protocol via a sequential Ugi four-component reaction and hydroxylaminolysis was used for the preparation of a panel of peptoid-based HDACi. Several compounds displayed potent activity against drug- sensitive and drug-resistant P. falciparum asexual blood stages, high parasite-selectivity and submicromolar activity against exo-erythrocytic forms of P. berghei. Our optimization study resulted in the discovery of the hit compound 1u which combines high activity against asexual blood stage parasites (Pf 3D7 IC50: 4 nM; Pf Dd2 IC50: 1 nM) and P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms (Pb EEF IC50: 25 nM) with promising parasite-specific activity (SIPf 3D7/HepG2: 2496, SIPf Dd2/HepG2: 9990, and SIPb EEF/HepG2: 400).

Keywords: Peptoid, HDAC inhibitor, histone deacetylase, malaria, Plasmodium falciparum

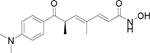

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were an estimated 216 million cases of malaria worldwide in 2017, and approximately 445,000 deaths due to this disease [1]. Six species of Plasmodium cause malaria in humans: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale curtisi, P. ovale wallikeri, P. malariae and the zoonotic simian parasite, P. knowlesi. P. falciparum causes the highest mortality, predominantly in Sub-Saharan Africa, with P. vivax also being responsible for significant global morbidity [1]. Considerable research activities have been devoted to the development of vaccines, however it is unlikely that a highly effective and broadly applicable malaria vaccine will be deployed in the near future [2]. Although the GlaxoSmithKlein (GSK) RTS,S malaria vaccine has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the WHO supports pilot studies [2], the efficacy of this vaccine against malaria in children inendemic areas was only moderate [3]. Vector control and antimalarial drugs therefore continue to be a mainstay for malaria prevention and treatment. While highly effective malaria treatment drug combinations are available, a major limitation is reduced clinical efficacy and/or development of drug-resistant Plasmodium parasites [4]. Parasite resistance has been reported to all currently used antimalarial drugs, including artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), the current gold standard treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria [5]. Spread of ACT- resistance to sub-Saharan Africa would be devastating, potentially impacting the significant improvements in malaria morbidity and mortality that have been made over the past decade. Alternatives to ACTs are urgently needed to prime the malaria drug discovery pipeline and to ensure that new treatment options are available in the event that ACTs fail. Next generation drugs for malaria also need to address the global agenda that is striving for elimination and ultimately eradication of this disease. This includes development of new drug candidates that are not only active against disease-causing asexual intraerythrocytic stage malaria parasites, but also against liver and sexual gametocyte stage parasites to prevent malaria symptoms from developing and to interrupt transmission [5–7].

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are emerging drug targets for various diseases and some HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) are already FDA approved for cancer therapy (vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat, and panobinostat) [8–11]. There is also growing evidence that HDACi may have therapeutic potential in a variety of non-cancer diseases including inflammation, immune disorders, HIV/AIDS, neurodegenerative diseases, and parasitic diseases [12–15]. Interestingly, among parasitic diseases some parasites appear to be more sensitive to HDACi than others [16,17]. Notably, P. falciparum parasites have been shown to be highly sensitive to pan-reactive HDACi (Table 1) [14,15].

Table 1.

In vitro activity profiles of selected HDAC inhibitors against malaria parasites.

| Name | HDACi Type |

Structure |

P. falciparum IC50 [nM] |

Cytotoxicity IC50 [nM] |

Selectivity Indexa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apicidinb | class I selective |

|

200 | 50 – 100 | <1 |

| Entinostatb | class I selective |

|

7,800 – 8,300 | >20,000 | >2 |

| Romidepsinc | class I selective |

|

90 – 130 | 1 – <5 | <1 |

|

Trichostatin A (TSA)d |

pan |  |

8 – 11 | 200 | 18 – 25 |

|

Vorinostat (SAHA)c |

pan | 120 – 190 | 5,170 – 5,500 | 27 – 46 | |

| Belinostatc | pan | 60–130 | 1,420 – 2,370 | 11– 40 | |

| Panobinostatc | pan | 10 – 30 | 70 – 180 | 2 – 18 |

Human HDACs (hHDACs) are divided into different classes according to their co-factor dependence and homology: class I (hHDAC1, 2, 3 and 8), class II (subdivided into class IIa: HDAC4, 5, 7 and 9; and class IIb: HDAC6 and 10) and class IV (HDAC11) are zinc-dependent isotypes, whereas class III HDACs are NAD+-dependent enzymes [20]. Thus far, five HDAC isoforms (PfHDACs) have been identified in P. falciparum parasites [15]. Three of these PfHDACs are homologues of zinc-dependent human class I (PfHDAC1) or class II HDACs (PfHDAC2 and 3), whereas two are class III homologues (PfSir2A and B) [15,21–23]. P. falciparum HDAC1 (PfHDAC1) is the only PfHDAC enzyme available in recombinant form [24,25], however its purity is low and catalytic activity in the absence of endogenous cofactors has been questioned [26]. PfHDAC1 has high amino acid sequence identity to hHDAC1 (61%) and hHDAC2 (62%), potentially compromising development of highly parasite-selective HDACi that target this enzyme with low activity against human class I human enzymes. Homology modeling studies suggest that the zinc-coordinating residues in HDACs and the tubular cavity between the zinc and the surface of the HDAC enzymes are well conserved between human class I HDAC enzymes and PfHDAC1 [16,17,27–30]. It is therefore not surprising that several studies with pan- and class I-selective human HDACi revealed potent in vitro anti-plasmodial activity in combination with varyingly levels of toxicity to human cells (see Table 1) [27–32]. Some HDACi have been shown to target multiple malaria parasite species (P. falciparum and P. vivax), to act against multi-drug resistant P. falciparum lines and, for a limited number, to have in vivo efficacy in animal models of malaria [14,15,29,32–35]. While most work to date has focused on asexual blood stage parasites, this class of compounds also has promising activity against liver- stage Plasmodium parasites [29,36,37] and activity against late stage (IV-V) gametocytes [36–39]. This raises the possibility of developing HDACi with potent activity against multiple Plasmodium life cycle stages and these recent findings underscore the potential for HDACi development for malaria therapy.

In addition to targeting multiple Plasmodium life cycle stages, other features of next generation anti-plasmodial HDACi should include potent killing of Plasmodium parasites and low toxicity to human cells as well as appropriate bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profiles for advancement to pre-clinical and early clinical studies [24–26]. Of particular relevance to malaria, there is growing evidence that there are intrinsic toxic side effects associated with inhibition of human class I isoforms and that this prevents the application of broad spectrum and class I-selective inhibitors to areas outside of oncology because of a small therapeutic window [40,41]. Due to their low toxicity to normal mammalian cells [40,41] we, and others, have hypothesized that hHDAC6 inhibitors might be a better starting point for the development of parasite-selective anti-plasmodial HDACi [37,42]. In a previous communication we reported the rational design and synthesis of a novel type of peptoid-based HDACi that preferentially targets human HDAC6 over representative examples of all other zinc dependent HDAC classes (class I: HDAC2; class IIa: HDAC4; and class IV: HDAC11) [43]. In this project we report a systematic and comprehensive structure-activity relationship (SAR) study of these peptoid-based HDACi as antiplasmodial agents. To this end, we developed a highly efficient one-pot, five-component approach for the diversity-oriented synthesis of our peptoid-based HDACi. All compounds were tested for in vitro activity against asexual intraerythrocytic stage P. falciparum parasites and cytotoxicity against mammalian cells. Selected compounds were further screened in vitro for their activity against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic liver stages as well as against different P. falciparum gametocyte stages [44,45]. Furthermore, we investigated the ability of these compounds to hyperacetylate histones in asexual stage P. falciparum parasites as a marker of HDAC inhibition. Herein, we present the design, multicomponent synthesis and antimalarial properties of a new type of parasite-selective antiplasmodial HDACi with dual stage activity.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. One-pot synthesis of peptoid-based HDACi.

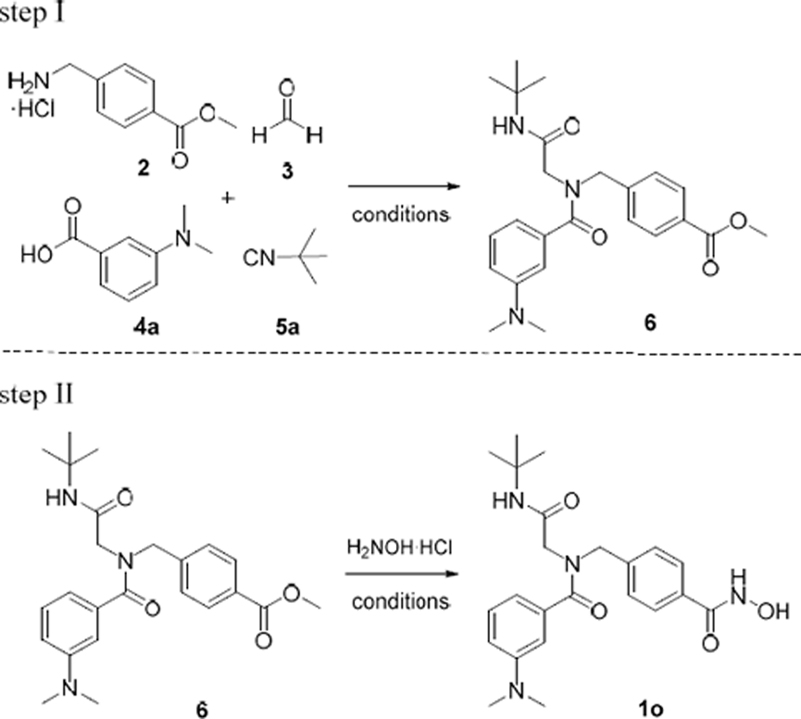

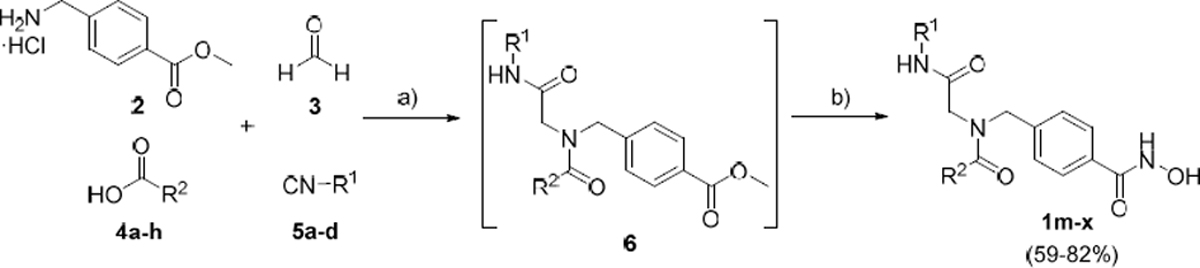

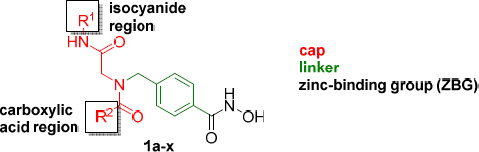

We previously described an efficient multi-component approach for the preparation of the peptoid-based HDACi 1a-l [43]. Briefly, this methodology was performed at room temperature under conventional reaction conditions using a two-step protocol. First, the Ugi four-component reaction (U-4CR) was used to afford the key intermediates of type 6 in 43–85% yield after purification by flash column chromatography (step I, Table 2). The target compounds were subsequently prepared in 42–69% yield by hydroxylaminolysis followed by purification via flash column chromatography (step II, Table 2). However, both steps required relatively long reaction times (step I: 72 h; step II: 16 h) [43].

Table 2.

Optimization of reaction conditions.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | MW [W] |

T [°C] |

time [min] |

yieldb [%] |

|

| step I | 1c | 150 | 45 | 60 | 63 |

| 2 | 150 | 45 | 120 | 79 | |

| 3 | 150 | 45 | 60 | 85 | |

| 4 | 150 | 45 | 30 | 68 | |

| 5 | 150 | 70 | 60 | 71 | |

| 6 | 150 | 55 | 60 | 76 | |

| step II | 7 | 150 | 45 | 20 | 63 |

| 8 | 150 | 45 | 30 | 77 | |

| 9 | 150 | 70 | 20 | 48 | |

| 10 | 150 | 55 | 20 | 75 | |

| 11 | 150 | 55 | 30 | 80 | |

All reactions were monitored by TLC.

Isolated yield after flash column chromatography.

All four components were added at once.

In this project, we aimed at improving the overall efficiency of our synthetic strategy by developing a one-pot, five-component approach. Furthermore, we utilized microwave irradiation in order to shorten reaction times. These modifications should enable higher yields and a more time efficient synthetic pathway for the preparation of peptoid-based HDACi. For this purpose, we initially investigated several reaction conditions independently for both steps using 1o as model compound. The results are summarized in Table 2. Based on our optimization previously done for the ‘classical’ U-4CR [43,46], we performed all microwave-assisted syntheses in dry methanol in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieve (4 Å MS) using a slight excess of the amine 2 (1.2 eq) and paraformaldehyde 3 (1.2 eq) compared to the carboxylic acid 4a (0.5 M concentration) and isocyanide 5a (0.5 M concentration) components.

We first attempted the microwave-assisted synthesis of the Ugi-product 6 by subjecting all four Ugi components and triethylamine to microwave irradiation (150 W, 45°C) for 60 min. The desired product 6 was isolated in a moderate yield of 63% (Table 2, entry 1). However, since a high yield in the first step is crucial for a successful one-pot approach, the U-4CR was further optimized. The imine formation represents a key step in the U-4CR. Thus, to optimize the reaction conditions, we focused on the pre-formation of the imine under microwave irradiation. A mixture of 4-aminomethyl benzoic acid methyl ester hydrochloride (2), paraformaldehyde (3), triethylamine and crushed 4 Å molecular sieves (4 Å MS) in dry methanol was irradiated at 45°C (150 W). The progress of the imine-formation was monitored by thin layer chromatography after 2, 5, 10 and 20 min. After 20 min of irradiation the imine-formation was completed and all further reactions were performed by a pre-formation of the imine under microwave irradiation at 45°C for 20 min before adding the isocyanide and carboxylic acid components. Next, we investigated the U-4CR at different temperatures and reaction times under microwave irradiation (step I, Table 2, entry 2–6). Best results were achieved at 45°C and 60 min (entry 3). These conditions provided the desired Ugi product in a very good isolated yield of 85%.

We next turned our attention towards the hydroxylaminolysis (step II, Table 2). In all cases, a purified sample of the methyl ester intermediate 6 was treated with a freshly prepared solution of hydroxylamine under microwave irradiation (150 W). In an initial attempt, we performed the hydroxylaminolysis at 45 °C for 20 min to afford the desired hydroxamic acid 1o in 63% isolated yield (entry 7). A slight increase in temperature from 45°C (entry 8) to 55 °C (entry 10, 11) and extension of the reaction time from 20 min (entry 10) to 30 min (entry 11) led to increased yields of 1o. In contrast, performing the reaction at even higher temperature (70°C) resulted in a decreased yield (48%, entry 9). Best results were achieved at 55°C and a reaction time of 30 min (80% isolated yield, entry 11).

In the last step to develop a rapid and diversity-oriented synthesis of peptoid-based HDACi of type 1, we combined the optimized conditions for both steps in a one-pot approach without isolation and purification of the Ugi product 6. By performing both optimized steps in the same reaction vessel in a sequential fashion under microwave irradiation, the desired target compound 1o could be obtained in less than two hours (Scheme 1). Purification by flash column chromatography afforded 1o in 72% yield.

Scheme 1.

Microwave-assisted multi-component synthesis of target compounds 1m-x via the optimized one-pot approach.a .aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) 2, 3, Et3N, MeOH, 4Å MS, 150 W, 45°C, 20 min; (ii) R1-NC, R2-COOH, 150 W, 45°C, 60 min; (b) H2NOH·HCl, Na, MeOH dry, 150 W, 55°C, 30 min.

This optimized one-pot, five-component protocol via a sequential Ugi-reaction and hydroxylaminolysis was then used for the preparation of the desired peptoid-based HDACi. In all cases, the crude products were purified by flash column chromatography and the HDACi 1m-x were isolated in 59–82% yield (Scheme 1). Taken together, this one-pot multi-component approach offers a lot of utility including (1) time efficiency, (2) high atom economy, (3) absence of protecting groups, and (4) multiple points of diversity.

2.2. In vitro inhibition of P. falciparum asexual intra-erythrocytic parasite growth, cytotoxicity and parasite selectivity.

All compounds were tested for activity against P. falciparum asexual intra-erythrocytic parasites using a tritiated hypoxanthine uptake assay. Compounds 1a-x had calculated log P values between 0.5 and 3.2 and were thus expected to be cell permeable (see Table 3 for calculated log P values). When tested for in vitro activity against the drug sensitive P. falciparum line 3D7, compounds 1a-x revealed 50% inhibitory concentration values (IC50s) in the range of 4–158 nM (Table 3). The activity of all compounds was either not significantly different to the reference HDACi vorinostat (p > 0.05), or significantly better (1a, 1d, 1g, 1h, 1i, 1k, 1m, 1t, 1v with p < 0.05). Based on our synthetic protocol the peptoid-based cap group can be further divided into a isocyanide (R1) and carboxylic acid (R2) region (Table 3). We could not identify clear structure-activity relationships (SARs) for the isocyanide region (Table 3). However, the screening provided interesting SARs with regards to the carboxylic acid region. Since the highest number of compounds (10 examples, 1f-i and 1p-u) were synthesized bearing cyclohexyl in the isocyanide region (R1), notable SARs of the carboxylic acid region will be discussed for compounds with R1 = cyclohexyl. Compound 1f (R2 = Ph) bearing no substitution at the phenylring in the carboxylic region exhibited an IC50 of 59 nM against the 3D7 line of P. falciparum. The replacement of the phenyl ring by a bulky naphthyl group (as in 1g) resulted in an increased antiplasmodial activity (Pf 3D7 IC50: 25 nM). The introduction of methyl groups in m- and/or p- position provided HDACi with somewhat improved activity compared to 1f (see 1i, 1q, 1s, 1t, Table 3), whereas compound 1r bearing a methyl group in o-position (R2 = 2-CH3-Ph, Pf 3D7 IC50: 76 nM) showed decreased activity. It is worth noting that a similar trend in regards to the position of methyl groups was observed in our previous report on alkoxyamide-based HDACi [36]. Interestingly, compound 1h (R2 = 4-Me2N-Ph, Pf 3D7 IC50: 9 nM) containing a N,N- dimethylamino group in p-position showed an ~7-fold higher activity than 1f, while the corresponding m-substituted analogue 1p (R2 = 3-Me2N-Ph, Pf 3D7 IC50: 44 nM) revealed reduced activity compared to 1h. Notably, the replacement of the N,N-dimethylamino group in 1h by an isosteric and less polar isopropyl group provided HDACi 1u (R2 = 4-i-Pr-Ph, Pf 3D7 IC50: 4 nM) which exhibited the highest activity of all synthesized compounds.

Table 3.

Calculated logP values, in vitro activity against asexual blood stages of P. falciparum parasites, cytotoxicity and selectivity indices of 1a – 1x.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co. | R1 | R2 | logPa |

P.falciparumbIC50 [nM] |

NFFC IC50[nM] |

SI ranged | |

| Pf3D7 | PfDd2 | ||||||

| 1a | t-Bu | 3,4-Me-Ph | 1.44(±0.53) | 20(±10) | 12(±8) | >10,000 | >500->833 |

| 1b | t-Bu | Ph | 0.52(±0.52) | 158(±51) | 54(±21) | >10,000 | >63->185 |

| 1c | t-Bu | 1-Naphthyl | 1.75(±0.52) | 59(±22) | 51(±20) | >10,000 | >169->196 |

| 1d | t-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.94(±0.55) | 11(±4) | 14(±6) | 4,480(±201) | 320–407 |

| 1e | t-Bu | 3,5-Me-Ph | 1.44(±0.53) | 50(±17) | 41(±23) | >10,000 | >200->244 |

| 1f | c-Hex | Ph | 1.36(±0.51) | 59(±11) | 118(±57) | >10,000 | >85->169 |

| 1g | c-Hex | 1-Naphthyl | 2.59(±0.52) | 25(±18) | 31(±12) | >10,000 | >323->400 |

| 1h | c-Hex | 4-Me2N-Ph | 1.77(±0.54) | 9(±3) | 15(±16) | 5,890(±1,660) | 393–654 |

| 1i | c-Hex | 3,5-Me-Ph | 2.28(±0.52) | 21(±16) | 33(±15) | >10,000 | >303->476 |

| 1j | 4-Tolyl | Ph | 1.89(±0.45) | 67(±23) | 53(±27) | >10,000 | >149->189 |

| 1k | 4-Tolyl | 1-Naphthyl | 3.12(±0.45) | 39(±17) | 33(±21) | >10,000 | >256->303 |

| 1l | 4-Tolyl | 4-Me2N-Ph | 2.31(±0.47) | 29(±14) | 20(±11) | 5,380(±4,990) | 186–269 |

| 1m | 4-Tolyl | 3,5-Me-Ph | 2.81(±0.45) | 33(±11) | 27(13) | >10,000 | >303->370 |

| 1n | 4-Tolyl | 3-Me2N-ph | 2.10(±0.47) | 38(±35) | 49(±14) | >10,000 | >204->263 |

| 1o | t-Bu | 3-Me2N-ph | 0.73(±0.54) | 47(±21) | 29(±18) | >10,000 | >213->345 |

| 1p | c-Hex | 3-Me2N-ph | 1.56(±0.54) | 44(±10) | 37(±27) | >10,000 | >227->270 |

| 1q | c-Hex | 3,4-Me-ph | 2.28(±0.52) | 31(±2) | 21(±9) | >10,000 | >323->476 |

| 1r | c-Hex | 2-Me-Ph | 1.82(±0.52) | 76(±26) | 57(±13) | >10,000 | >132->175 |

| 1s | c-Hex | 3-Me-Ph | 1.82(±0.52) | 43(±17) | 48(±10) | >10,000 | >233->208 |

| 1t | c-Hex | 4-Me-Ph | 1.82(±0.52) | 16(±8) | 11(±1) | >3,000 | >188->273 |

| 1u | c-Hex | 4-i-Pr-Ph | 2.69(±0.52) | 4(±1) | 1(±1) | >4,000 | >1000->4000 |

| 1v | n-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 1.31(±0.52) | 14(±4) | 14(±4) | >2,000 | >143 |

| 1w | n-Bu | 3-Me2N-ph | 1.10(±0.53) | 51(±26) | 43(±8) | >10,000 | >233->196 |

| 1x | n-Bu | 3,5Me-Ph | 1.81((±0.52) | 47(±27) | 56(±16) | >10,000 | >178->213 |

|

SAHA CQ |

0.86(±0.21) 4.69(0.32) |

139(±73) 11(±2) |

146(±22) 49(±17) |

4,900(±1,240)e 46,608(±14,420) |

33–35 953–3628 |

||

logP values were calculated using ACD/ChemSketch freeware version 12.01.

Threeindependent assays were carried out, each carried out in triplicate wells. Resistance indices (Ri; Dd2 IC50/3D7 IC50) range from 0.3–2.0 for all HDACi while the Ri of chloroquine is 4.6.

Two independent assays were carried out, each carried out in triplicate wells. For compounds where IC50 was not achieved in one or more assays, the highest common test concentration is given.

SI= NFF IC50/ P. falciparum IC50 – larger values indicate greater parasite selectivity.

Data previously reported [39].

Subsequently, we assessed the antiplasmodial activity of 1a-x against the multidrug resistant P. falciparum Dd2 line. All compounds displayed nanomolar activity against this line, with IC50 values ranging from 1 – 118 nM (Table 3) and all compounds exceeded the potency of vorinostat (SAHA, Pf Dd2 IC50: 146 nM). Overall, we observed similar IC50 values and structure-activity relationships against drug resistant (Dd2) and drug sensitive (3D7) asexual P. falciparum parasites indicating that resistance mechanisms developed in the Dd2 line do not affect the in vitro activity of this series of antiplasmodial HDACi. Again, compound 1u (R1 = c-Hex; R2 = 4- i-Pr-Ph) was the most active compound from this series (Pf Dd2 IC50: 1 nM).

To investigate the parasite-specific selectivity of the peptoid-based HDACi, cytotoxicity of 1a-x was tested against normal human neonatal foreskin fibroblasts (NFFs). The cytotoxicity and selectivity indices (SIs) of 1a-x are summarized in Table 3. Interestingly, the substitution in the isocyanide region (R1) had little impact on the cytotoxicity, whereas a clear trend was observed in the case of the carboxylic acid region (R2). Compounds 1d, 1h, 1l, and 1t-v with a p-substituted carboxylic acid component (R2) showed cytotoxicity in the single digit micromolar concentration range. In contrast, all other compounds revealed low cytotoxicity (NFF IC50:>10,000 nM). Interestingly, compounds with substituents in m- and p-position (see compounds 1a and 1q) did not show cytotoxicity at the highest concentration tested. The reason for the increased cytotoxicity of derivatives with mono-substitution in p-position of the carboxylic acid region is not yet known. However, these data indicate that derivatives bearing substituents in meta- or ortho-position of the carboxylic acid region might be a good starting point for the development of analogues with reduced cytotoxicity.

A comparison of the IC50 values for asexual blood stage P. falciparum parasites with those obtained for NFF cells indicates an encouraging parasite-selectivity for this novel class of HDACi. All compounds, except 1b and 1f, had at least a 100 fold higher activity against asexual blood stage parasites vs mammalian cells (Table 3), whereas the reference HDACi vorinostat showed only modest parasite-selectivity (SI range: 33–35). The highest parasite-selectivity was observed in the case of 1u (SI range: >1000 – >4000).

In order to identify HDACi with potent and parasite-specific activity, all compounds with an average activity against asexual blood stages of ≤ 30 nM were further tested for cytotoxicity against mammalian HepG2 cells (Table 4). In general, the HepG2 line was less sensitive to the HDACi of type 1 compared to NFF cells. Four of the eleven compounds tested revealed IC50 values between 5.81 and 9.99 µM, two had moderate cytotoxicity in the range of 11.90 to 12.34 µM, while five compounds showed low cytotoxicity with IC50s > 20 µM. Notably, compound 1g showed no cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells at the highest concentration tested (HepG2 IC50 > 50 µM). Again, we observed the trend that derivatives with a mono-substitution in p-position of the carboxylic acid region exhibited higher cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells than the other compounds. A comparison of activity against asexual blood stage parasites vs HepG2 cells showed that all compounds have a selectivity index of at least 200 (Table 4). In contrast, vorinostat showed only low parasite-selectivity (SI range: 17–18). The highest parasite- selectivity was found for compound 1u (SI range: 2496–9990). In summary, the peptoid-based HDACi possess potent activity against asexual blood stage parasites and, compared to other HDACi with anti-plasmodial activity (see Table 1), an encouraging parasite-specific activity.

Table 4.

Cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells and selectivity indices of 1a, 1d, 1g-i, 1l, 1m, 1q, and 1t-v.

| Co. | R1 | R2 | HepG2 IC50[Μm] |

95%CI forHepG2 IC50 |

SI rangea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | t-Bu | 3,4-Me-Ph | 25.94 | 19.65–34.24 | 1295–2158 |

| 1d | t-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 11.90 | 8.47–16.70 | 850–1082 |

| 1g | c-Hex | 1-Naphthyl | >50 | >1613–>2000 | |

| 1h | c-Hex | 4-Me2N-Ph | 7.80 | 5.43–11.21 | 520–867 |

| 1i | c-Hex | 3,5-Me-Ph | 21.15 | 17.62–25.38 | 642–1010 |

| 1l | 4-Tolyl | 4-Me2N-Ph | 5.81 | 4.04–8.35 | 200–291 |

| 1m | 4-Tolyl | 3,5-Me-Ph | 21.39 | 16.82–27.20 | 648–793 |

| 1q | c-Hex | 3,4-Me-Ph | 21.98 | 19.11–25.28 | 710–1048 |

| 1t | c-Hex | 4-Me-Ph | 12.34 | 7.96–19.14 | 769–1118 |

| 1u | c-Hex | 4-i-Pr-Ph | 9.99 | 7.14–13.99 | 2496–9990 |

| 1v | n-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 6.99 | 5.21–9.39 | 499 |

| 2.51 | 1.63–3.86 | 17–18 |

SI = HepG2 IC50/P. falciparum IC50 – larger values indicate greater parasite selectivity.

2.3. Inhibition of human HDAC1 and HDAC6.

The cytotoxicity screening against mammalian cells revealed some differences in the cytotoxicity of the peptoid-based HDACi (Table 3 and Table 4). In order to investigate whether the differences in the toxicity against mammalian cells correlates with different human HDAC isoform profiles, we decided to screen selected compounds in a biochemical assay against hHDAC1 and hHDAC6 using ZMAL (Z-(Ac)Lys-AMC) as substrate. hHDAC6 was selected because several peptoid-based HDACi were previously identified as preferential hHDAC6 inhibitors [43,47]. Toxic side effects of HDACi have been primarily associated with inhibition of human class I isoforms [40]. hHDAC1 was therefore chosen as representative class I isoform. The three compounds with the highest cytotoxicity (1l, 1u and 1v) and the three compounds with the lowest toxicity (1a, 1g, and 1q) against HepG2 cells were chosen for the screening against hHDAC1 and hHDAC6. The results are presented in Table 5. As expected, all compounds revealed potent activity against HDAC6 with IC50 values ranging from 0.030 – 0.064 µM. Interestingly, we observed some noteworthy differences in the activity against hHDAC1. Compounds 1a, 1g, and 1q demonstrated only weak activity against hHDAC1 (IC50: 0.304 –0.552 µM), whereas 1l, 1u and 1v revealed a more potent inhibition of hHDAC1 (IC50: 0.040 –0.086 µM). Most probably, the higher cytotoxicity of 1l, 1u and 1v against human cells is therefore related to the increased activity against human class I isoforms.

Table 5.

Activities of compounds 1a, 1g, 1l, 1q, 1u, 1v and the reference HDACi SAHA against human HDAC1 (hHDAC1) and HDAC6 (hHDAC6).

| Co. | R1 | R2 | hHDAC1 IC50 [μM] |

hHDAC6 IC50 [μM] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | t-Bu | 3,4-Me-Ph | 0.428(±0.015) | 0.057(±0.007) |

| 1g | c-Hex | 1-Naphthyl | 0.552(±0.007) | 0.031(±0.001) |

| 1l | 4-Tolyl | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.080(±0.008) | 0.030(±0.005) |

| 1q | c-Hex | 3,4-Me-Ph | 0.304(±0.032) | 0.032(±0.002) |

| 1u | c-Hex | 4-i-Pr-Ph | 0.086(±0.018) | 0.064(±0.006) |

| 1v | n-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.040(±0.006) | 0.035(±0.002) |

| SAHA | 0.079(±0.010) | 0.055(±0.011) |

2.4. Effect of peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors on P. falciparum histone acetylation

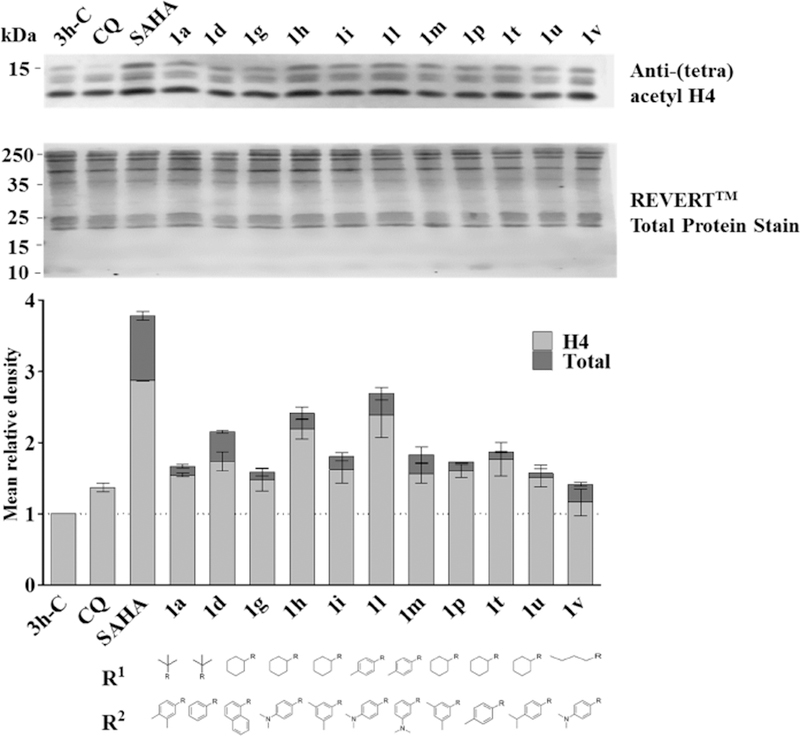

The effect of selected compounds (1a, 1d, 1g, 1h, 1i, 1l, 1m, 1q, 1t, 1u, 1v) on P. falciparum histone H4 hyperacetylation was assessed via protein hyperacetylation assays using trophozoite stage parasites treated for 3 h with 5x IC50 concentrations of each compound. Unlike the HDAC inhibitor control, SAHA, which showed ~2.5–3.5 fold increased acetylation of bands corresponding to either H4 (~11 kDa band; Figure 1 light grey) or H4 plus cross reactive bands (H2B/H2Bv (~13–14 kDa); H2A.Z (~16 kDa); Figure 1 dark grey), the effect of the eleven peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors was variable. Three compounds (1d, 1h and 1l) caused ~2-fold or greater increase in hyperacetylation, while the remainder of the compounds caused only ~1.0– 1.5- fold increases.

Figure 1.

Hyperacetylation of P. falciparum histone H4 by peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors. Western blot analysis of P. falciparum 3D7 protein lysates prepared from trophozoite-stage infected erythrocytes treated for 3 h with 5x IC50 of test or control compounds. Negative controls were parasites exposed to the antimalarial drug chloroquine (CQ) or compound vehicle (0.2% DMSO; 3h-C). (A) Western blot was carried out using anti-(tetra) acetyl-histone H4 antibody and IRDye 680 goat anti-rabbit conjugate secondary antibody. Total protein per lane was detected using REVERTTM Total Protein Stain on the same membrane. Representative Western blot shown. Protein molecular weight marker bands (kDa) are indicated. (B) Graph showing mean relative density (+/−SD) for two independent Western blot experiments. Western density signals were normalized to total protein load in the respective lane and expressed as fold change compared to the 3h-C DMSO vehicle control (taken as 1.0; dotted line). Data are mean (±) SD for two independent experiments. Dark grey bars show total density for all bands (~11 kDa band corresponds to the correct size of histone H4, with the doublet likely cross reactivity with acetylated forms of H2B/H2Bv (~13–14 kDa) and the ~16 kDa band cross reactivity with H2A.Z) while light grey bars shows signal corresponding to the ~11 kDa H4 band only.

2.5. In vitro activity against early-stage and late-stage P. falciparum gametocytes and P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms.

The potential of this compound class to act as antiplasmodials with dual- or multi-stage activity was determined by evaluating their gametocytocidal potency and liver stage activity. Compounds 1a, 1d, 1g, 1h, 1i, 1l and 1m were first screened for their inhibition of gametocyte development from early stage I to stage III gametocytes (Pf ESG) and from late stage IV to stage V gametocytes (Pf LSG) using an imaging-based viability assay [44,45]. The results are summarized in Table 6. All five compounds were found to have only moderate activity against early (Pf ESG IC50 >2 µM) and late stage gametocytes (Pf LSG IC50 >1 µ M). The best activity against early and late stage gametocytes was observed for compound 1h (Pf ESG IC50 2.36 µM; Pf LSG IC50 1.81 µ M). To further investigate the activity of this class of compounds against mature stage V gametocytes, compounds 1a-x were tested in an ATP bioluminescence assay [48] at two fixed concentrations of 0.5 and 5 µM. The most promising compounds from this primary screen were subsequently tested in dose response to determine IC50 values (Table 6). In good agreement with the results from the imaging-based viability assay, the compounds showed only moderate activity in the ATP-based assay (IC50 >2 µM). Again, compound 1h showed the highest activity of all tested compounds (IC50 2.46 µM).

Table 6.

Activity of peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors against different P. falciparum gametocyte stages.

| Co. | R1 | R2 | imaging-based viability assay | ATP assay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pf ESGa IC50 [μM] |

Pf LSGb IC50 [μM] |

Pf stage V gametocytesc IC50 [μM] |

|||

| 1a | t-Bu | 3,4-Me-Ph | 86%d | 92%d | nd |

| 1d | t-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 4.41±0.66 | 2.72±0.48 | 7.69±3.26 |

| 1g | c-Hex | 1-Naphthyl | 4.46±0.54 | 97%d | nd |

| 1h | c-Hex | 4-Me2N-Ph | 2.36±0.31 | 1.81±0.07 | 2.46±0.89 |

| 1i | c-Hex | 3,5-Me-Ph | 8.37±0.85 | 5.25±0.20 | 15.7±1.60 |

| 1j | 4-Tolyl | Ph | nd | nd | 9.41±5.12 |

| 1l | 4-Tolyl | 4-Me2N-Ph | 5.90±0.34 | 3.89±0.44 | 4.35±2.16 |

| 1m | 4-Tolyl | 3,5-Me-Ph | 7.60±0.17 | 7.28±0.15 | 10.1±3.72 |

| 1q | c-Hex | 3,4-Me-Ph | nd | nd | 13.12±2.25 |

| 1u | c-Hex | 4-i-Pr-Ph | nd | nd | 7.74±0.56 |

| SAHA | 1.41±0.13e | 0.81±0.21e | 2.80±0.83 | ||

P. falciparum NF54 early stage gametocytes (I-III); n=2, each in duplicate wells; artesunate (IC50: 0.003±0.001 μM) and pyronaridine (IC50: 0.029±0.001 μM) were used as reference compounds.

P. falciparum NF54 late stage gametocytes (IV-V); n=2, each in duplicate wells; artesunate (IC50: 0.008±0.0008 μM) and pyronaridine (IC50: 1.71±0.33 μM) were used as reference compounds.

P. falciparum stage V gametocytes; at least two independent experiments, each in duplicate wells; epoxomicin (IC50: 0.007±0.007 μM), methylene blue (IC50:210.48±0.35 μM) and chlorotonil A (IC50: 0.041±0.021 μM) were used as reference compounds.

Inhibition at 40 μM.

Data previously reported [39]. nd, not determined.

Compounds with activity against liver stages (exo-erythrocytic forms) can potentially prevent disease development and be used in chemoprotection. We therefore profiled key compounds of this series for their activity against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms (Pb EEF) as described previously [49]. In contrast to the activity against gametocytes, several compounds displayed potent activity against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms (Table 7). Six out of eleven compounds tested (1d, 1h, 1l, 1t, 1u and 1v) revealed submicromolar activity with IC50 values ranging from 0.025 to 0.91 µM. The two most potent compounds 1t (Pb EEF IC50: 0.084 µM) und 1u (Pb EEF IC50: 0.025 µM) both bear a cyclohexyl residue in the isocyanide region and a p-alkylsubstituted phenyl group in the carboxylic acid region. These data indicate that this substitution pattern might be important for the development of peptoid-based HDACi with improved activity against liver stages.

Table 7.

Activity of peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms.

| Co. | R1 | R2 | Pb EEFa IC50 [μM] |

95% CI for Pb EEF IC50 |

HepG2 IC50 [μM] |

95% CI for HepG2 IC50 |

EEF SIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | t-Bu | 3,4-Me-Ph | 1.35 | 0.65–2.80 | 25.94 | 19.65–34.24 | 19 |

| 1d | t-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.91 | 0.31–2.73 | 11.90 | 8.47–16.70 | 13 |

| 1g | c-Hex | 1-Naphthyl | 10.64 | 3.26–34.74 | >50 | >5 | |

| 1h | c-Hex | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.57 | 0.17–1.86 | 7.80 | 5.43–11.21 | 14 |

| 1i | c-Hex | 3,5-Me-Ph | 1.84 | (very wide) | 21.15 | 5.43–11.21 | 12 |

| 1l | 4-Tolyl | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.58 | (very wide) | 5.81 | 4.04–8.35 | 10 |

| 1m | 4-Tolyl | 3,5-Me-Ph | 5.55 | (very wide) | 21.39 | 16.82–27.20 | 4 |

| 1q | c-Hex | 3,4-Me-Ph | 1.47 | 0.64–3.35 | 21.98 | 19.11–25.28 | 15 |

| 1t | c-Hex | 4-Me-Ph | 0.084 | 0.050–0.14 | 12.34 | 7.96–19.14 | 147 |

| 1u | c-Hex | 4-i-Pr-Ph | 0.025 | 0.013–0.048 | 9.99 | 7.14–13.99 | 400 |

| 1v | n-Bu | 4-Me2N-Ph | 0.21 | 0.11–0.37 | 6.99 | 5.21–9.39 | 33 |

| SAHA | 0.0077 | 0.0055–0.011 | 2.51 | 1.63–3.86 | 326 | ||

| ATQ | 0.000014 | 0.000012–0.000017 | >0.50 | n/a | >35,000 |

P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms (EEF).

SI = (mammalian cell IC50)/(Pb EEF IC50) – larger values indicate greater malaria parasite selectivity. CI, confidence interval.

When we compared the IC50 values for P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms with those obtained for HepG2 cells, we found that most compounds showed only moderate parasite-specific activity (SIHepG2/Pb EEF: 4–33). However, 1t and 1u, the compounds with the best activity against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms, revealed high parasite-selectivity with selectivity indices of > 100 (1t: SIHepG2/Pb EEF: 147 and 1u: SIHepG2/Pb EEF: 400).

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a highly efficient and diversity-oriented one-pot multi- component approach for the synthesis of peptoid-based HDACi. The optimized microwave- assisted protocol allowed the synthesis of the target compounds in less than two hours via an Ugi four-component reaction followed by the introduction of the hydroxamic acid in a post-Ugi transformation. A series of 24 peptoid-based HDACi was evaluated for anti-plasmodial activity and cytotoxicity against mammalian cells. All compounds displayed potent submicromolar activity against drug sensitive and drug resistant asexual blood stage P. falciparum parasites with IC50 values ranging from 4–158 nM (3D7 line) and 1–118 nM (Dd2 line). Key compounds were further tested for activity against different P. falciparum gametocyte stages as well as against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms. While only moderate activity was found against gametocytes, several compounds revealed submicromolar activity against P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms. The most promising compound from this series, compound 1u, combines high activity against asexual blood stage parasites (Pf 3D7 IC50: 4 nM; Pf Dd2 IC50: 1 nM) and P. berghei exo-erythrocytic forms (Pb EEF IC50: 25 nM) with promising parasite-specific activity (SIPf 3D7/HepG2: 2496, SIPf Dd2/HepG2: 9990, and SIPb EEF/HepG2: 400).

Taken together, this study provides further evidence that hHDAC6 inhibitors are a promising starting point for the development of antiplasmodial drug candidates. Furthermore, the findings described in this work thus offer a promising gateway for more elaborate studies to further optimize the activity of this class of HDACi towards the different malaria parasite life cycle stages. The described one-pot synthesis is suitable for various alterations of this scaffold. Future structural modifications should include the variation of the linker and linker lengths, substitution of the α-carbon as well as prodrugs strategies. The suggested modifications are underway and will deliver valuable structure-activity relationships and might provide pioneering insights towards design principles to specifically target the different life cycle stages.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

All chemicals and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, Acros Organics, Carbolution Chemicals) and used as purchased without further purification. All microwave-assisted reactions were carried out with a CEM Focused Microwave System, Model Discover. The progress of all reactions was monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using Merck precoated silica gel plates (with fluorescence indicator UV254). Components were visualized by irradiation with ultraviolet light (254 nm) or staining in potassium permanganate solution following heating. Flash column chromatography was performed using prepacked silica cartridge with the solvent mixtures specified in the corresponding experiment. Melting points (mp) were taken in open capillaries on a Mettler FP 5 melting-point apparatus and are uncorrected. Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 300, 500 or 600 using DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 as solvents. Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm), relative to residual solvent peak for 1H and 13C. 1H NMR signals marked with an asterisk (*) correspond to peaks assigned to the minor rotamer conformation. Elemental analysis was performed on a Perkin Elmer PE 2400 CHN elemental analyzer. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) analysis was performed on a UHR-TOF maXis 4G, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen by electrospray ionization (ESI). Analytical HPLC analysis were carried out on a Varian Prostar system equipped with a Prostar 410 (autosampler), 210 (pumps) and 330 (UV-detector) using a Phenomenex Luna 5u C18(2) 1.8 µ m particle (250 mm × 4.6 mm) column, supported by Phenomenex Security Guard Cartridge Kit C18 (4.0 mm × 3.0 mm). UV absorption was detected at 254 nm with a linear gradient of 10% B to 100% B in 20 min using HPLC-grade water +0.1% TFA (solvent A) and HPLC-grade acetonitrile +0.1% TFA (solvent B) for elution at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The purity of all final compounds was 95% or higher.

4.1.1. Experimental Data.

General procedures for the synthesis of antiplasmodial HDAC inhibitors and compound characterization data for 1m-x are given below. The syntheses of compounds 1a-l have been previously described by our group [43].

4.1.1.1. Synthesis of antimalarial HDAC inhibitors. General procedure for the preparation of target compounds 1m-x.

A mixture of 4-aminomethyl benzoic acid methyl ester hydrochloride (2) (121 mg, 0.6 mmol, 1.2 eq), paraformaldehyde (3) (18 mg, 0.6 mmol, 1.2 eq), triethylamine (83 µl, 0.6 mmol, 1.2 eq), and 50 mg of crushed molecular sieves (MS) 4 Å in dry methanol (1 mL, 0.5 M) was added into a 10 mL glass pressure microwave tube equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar. The tube was closed with a silicon septum and the reaction mixture was subjected to microwave irradiation (Discover mode; power: 150 W; hold time: 20 min; temperature: 45 °C; PowerMax-cooling mode) under medium speed magnetic stirring. Next, the appropriate carboxylic acid (4a-h) (0.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) and isocyanide (5a-d) (0.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) components were added and the reaction mixture was again irradiated at 45°C for 60 min (150W). Subsequently, a mixture of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (348 mg, 5.0 mmol. 10 eq) in a sodium methanolate solution, freshly prepared from dry methanol (8 mL) and sodium (175 mg, 7.5 mmol, 7.5 eq) was added and the reaction mixture was subjected to microwave irradiation at 55°C for 30 min (150W). After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Water (15 mL) was added and the pH was adjusted to a pH 7–8 using 4 M HCl. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 20 mL), the combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated in vacuum. The crude products were purified by flash column chromatography (prepacked silica cartridge, dichloromethane-dichloromethane/methanol (70:30), gradient: 90:10 70:30 in 20 min) to yield the desired products 1m-x.

4.1.1.2. Methyl 4-((3,5-dimethyl-N-(2-oxo-2-(p-tolylamino)ethyl)benzamido)methyl)benzoate (1m).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3,5-dimethylbenzoic acid (4b) and p-tolyl isocyanide (5b) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 76%, mp 183 °C; tR: 14.57 min, purity: 99.4%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.21 (s, 1H), 9.93*/9.77 (2 x s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.84–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.55–7.25 (m, 4H), 7.20–6.93 (m, 5H), 4.72/4.58* (2 x s, 2H), 4.10*/3.92 (2 x s, 2H), 2.24 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO): δ = 171.7, 166.55, 166.1, 164.0, 140.6, 140.4, 137.7, 137.6, 136.4, 136.0, 135.9, 135.8, 132.5, 132.1, 131.8, 131.7, 130.9, 130.8, 129.15, 127.7, 127.2, 127.1, 126.9, 124.1, 124.1, 119.3, 119.0, 53.2, 51.7, 48.7, 48.1, 20.8, 20.4. HRMS (ESI) Anal. Calcd. for C26H28N3O4: 446.2074 [M+H]+, Found: 446.2077.

4.1.1.3. 3-(Dimethylamino)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-N-(2-oxo-2-(p-tolylamino)-ethyl)benzamide (1n).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid (4a) and p-tolyl isocyanide (5b) according to the general procedure. Yellow solid; yield 68%; mp 169°C; tR: 10.33 min, purity: 96.2%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.18 (s, 1H), 9.94*/9.80 (2 x s,1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.86–7.67 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.30–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.18–7.03 (m, 2H),6.85–6.58 (m, 3H), 4.72/4.62* (2 x s, 2H), 4.12*/3.94 (2 x s, 2H), 3.01 (s, 6H), 2.83*/2.25 (2 x s,3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.9, 166.6, 166.1, 163.9, 149.9, 140.5, 136.5, 136.3,135.9, 132.35, 132.0, 131.7, 127.6, 127.1, 127.0, 126.6, 119.2, 119.0, 113.9, 113.8, 113.2, 109.7,53.15, 51.5, 48.6, 48.1, 39.9, 39.5, 20.3. HRMS (ESI) Anal. Calcd. for C26H29N4O4: 461.2183 [M+H]+, Found: 461.2181.

4.1.1.4. N-(2-(tert-Butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-3-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)- benzyl)benzamide (1o).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid (4a) and tert-butyl isocyanide (5a) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 72%; mp 138 °C; tR: 8.68 min, purity: 96.4%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.85–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.52– 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.41–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.27–7.15 (m, 1H), 6.85–6.57 (m, 3H), 4.61/4.51* (2 x s, 2H), 3.88*/3.67 (2 x s, 2H), 2.89/2.78* (2 x s, 6H), 1.25*/1.21 (2 x s, 9H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.9, 167.1, 166.6, 164.0, 150.0, 140.55, 136.7,136.6, 131.7, 129.0, 129.0, 127.7, 127.2, 127.1, 126.7, 114.2, 113.8, 113.2, 110.1, 109.7, 52.9,51.2, 50.3, 50.2, 48.5, 47.3, 39.9, 28.6, 28.4. Anal. Calcd. for C23H31N4O4: 427.2340 [M+H]+,Found: 423.2342.

4.1.1.5. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-3-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)- benzyl)benzamide (1p).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid (4a) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 66%; mp 146 °C; tR: 9.53 min, purity: 98.2%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s,1H), 7.86–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.51–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.28–7.12 (m, 1H), 6.89–6.55 (m, 3H), 4.64/4.54*(2 x s, 2H), 3.90*/3.70 (2 x s, 2H), 3.64–3.45 (m, 1H), 2.89/2.79* (2 x s, 6H), 1.81–1.47 (m, 5H),1.37–0.99 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.9, 166.7, 166.4, 164.0, 163.8, 150.0,140.5, 136.6, 136.5, 131.7, 129.0, 127.7, 127.2, 127.1, 126.7, 114.1, 113.75, 113.2, 110.05,109.7, 53.0, 50.9, 48.5, 47.7, 47.15, 39.9, 32.4, 32.3, 25.1, 24.4. HRMS (ESI) Anal. Calcd. For C25H33N4O4: 453.2496 [M+H]+, Found: 453.2502.

4.1.1.6. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-3,4-dimethyl- benzamide (1q).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3,4-dimethylbenzoic acid (4c) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 80%; mp 146 °C; tR: 13.67 min, purity: 98.8%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.92–7.63 (m, 3H), 7.51–7.01 (m, 5H), 4.64/4.53* (2 x s, 2H), 3.88*/3.68 (2 x s, 2H), 3.63–3.45 (m, 1H),2.23*/2.22 (2 x s, 6H), 1.81–1.44 (m, 5H), 1.37–0.98 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ171.4, 166.6, 163.9, 140.5, 137.8, 136.15, 133.5, 131.65, 129.2, 127.6, 127.0, 126.75, 124.0,52.9, 51.0, 48.7, 47.55, 47.15, 32.15, 25.1, 24.3, 19.1. Anal. Calcd. for C25H32N3O4: 438.2387[M+H]+, Found: 438.2391.

4.1.1.7. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-2- methylbenzamide (1r).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 2-dimethylbenzoic acid (4d) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 69%; mp 142 °C; tR: 12.71 min, purity: 98.8%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.19 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H),7.85–7.54 (m, 3H), 7.46–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.12 (m, 5H), 4.68*/4.35 (2 x s, 2H), 3.89*/3.57 (2 x s, 2H), 3.59–3.46 (m, 1H), 2.32*/2.23 (2 x s, 3H), 1.91–1.44 (m, 5H), 1.34–0.91 (m, 5H).13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.1, 171.05, 166.2, 166.2, 163.95, 163.8, 140.6, 139.8,136.1, 135.95, 134.3, 134.0, 131.9, 131.8, 130.25, 130.2, 128.75, 127.8, 127.2, 127.1, 127.0,125.7, 125.65, 125.55, 125.5, 52.0, 50.3, 48.1, 47.7, 47.6, 46.2, 39.5, 32.4, 32.2, 25.2, 25.1, 24.5,24.4, 18.6, 18.6. Anal. Calcd. for C24H30N3O4: 424.2231 [M+H]+, Found: 424.2228.

4.1.1.8. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-3- methylbenzamide (1s).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3-dimethylbenzoic acid (4e) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 69%; mp 164 °C; tR: 13.00 min, purity: 99.3%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.21 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.83–7.66 (m, 3H), 7.42–7.37 (m, 1H), 7.34–7.17 (m, 5H), 4.66/4.52* (2 x s, 2H), 3.90*/3.68 (2 x s, 2H), 3.61–3.48 (m, 1H), 2.32/2.30* (2 x s, 3H), 1.81–1.47 (m, 5H), 1.35–0.97 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.5, 166.6, 166.3, 164.1, 164.0, 140.5, 140.2, 137.85, 137.7, 136.1, 135.9, 131.7, 130.1, 128.25, 127.7, 127.25, 127.1, 127.0, 126.85, 123.65, 53.0, 51.0, 48.7, 47.6, 45.9, 39.5, 32.4, 32.25, 25.1, 24.5, 24.4, 20.9. Anal. Calcd. for C24H30N3O4: 424.2231 [M+H]+, Found: 424.2233.

4.1.1.9. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-4- methylbenzamide (1t).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 4-dimethylbenzoic acid (4f) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 82%; mp 187 °C; tR: 13.00 min, purity: 99.1%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.21 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.86–7.67 (m, 3H), 7.46–7.26 (m, 4H), 7.27–7.18 (m, 2H), 4.64/4.54* (2 x s, 2H), 3.89*/3.70 (2 x s, 2H), 3.61–3.48 (m, 1H), 2.33/2.31* (2 x s, 3H), 1.77–1.49 (m, 5H), 1.33–1.00 (m, 5H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.35, 166.5, 163.9, 140.4, 139.1, 133.1, 131.6, 128.7, 127.6, 127.0, 126.6, 52.9, 51.05, 48.7, 47.5, 47.1, 32.1, 25.05, 24.3, 20.8. Anal. Calcd. For C24H30N3O4: 424.2231 [M+H]+, Found: 424.2229.

4.1.1.10. N-(2-(Cyclohexylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-4- isopropylbenzamide (1u).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 4-isoproplbenzoic acid (4g) and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5c) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 60%; mp 167 °C; tR: 14.76 min, purity: 96.9%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.89–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.49–7.16 (m, 6H), 4.63/4.54* (2 x s, 2H), 3.88*/3.70 (2 x s, 2H), 3.61–3.46 (m, 1H), 3.06–2.80 (m, 1H), 1.88–1.45 (m, 5H), 1.37–0.91 (m, 5H), 1.20 (d, 6H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.5, 166.6, 166.4, 164.0, 163.9, 150.0, 140.6, 133.6, 131.7, 127.7, 127.3, 127.1, 126.9, 126.8, 126.7, 126.4, 126.2, 51.2, 48.8, 47.6, 33.3, 32.5, 32.25, 25.2, 24.5, 24.4, 23.7. Anal. Calcd. for C26H34N3O4: 452.2544 [M+H]+, Found: 452.2544.

4.1.1.11. N-(2-(Butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-4-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)- benzamide (1v).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 4-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid (4h) and butyl isocyanide (5d) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 73%; mp 169 °C; tR: 9.08 min, purity: 98.7%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.82–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.49–7.19 (m, 4H), 6.81–6.57 (m, 2H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.81 (s, 2H), 3.07 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 1.51–1.14 (m, 4H), 0.87 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO): δ = 171.6, 167.7, 163.9, 151.2, 140.7, 131.6, 128.5, 127.0, 122.05, 110.9, 39.6, 38.1, 31.0, 19.4, 13.5. Anal. Calcd. for C23H31N4O4: 427.2340 [M+H]+, Found: 427.2337.

4.1.1.12. N-(2-(Butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-3-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)- benzamide (1w).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3-(dimethylamino)benzoic acid (4a) and butyl isocyanide (5d) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 59%; mp 116 °C; tR: 8.84 min, purity: 96.3%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.00 (s, 1H), 9.07 (s, 1H), 7.94–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.82–7.64 (m, 2H), 7.45–7.11 (m, 3H), 6.90–6.54 (m, 3H), 4.64/4.55* (2 x s, 2H), 3.91*/3.71 (2 x s, 2H), 3.18–2.98 (m, 2H), 2.89/2.79* (2 x s, 6H), 1.47–1.16 (m, 4H), 1.00–0.77 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ = 171.9, 167.6, 167.3, 163.9, 163.8, 150.0, 140.5, 136.6, 136.45, 131.7, 129.0, 127.7, 127.2, 127.1, 126.65, 114.0, 113.8, 113.2, 110.0, 109.8, 53.1, 50.9, 48.5, 47.35, 39.9, 39.5, 38.25, 31.2, 31.1, 19.5, 13.6. Anal. Calcd. for C23H31N4O4: 427.2340 [M+H]+, Found: 427.2337.

4.1.1.13. N-(2-(Butylamino)-2-oxoethyl)-N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-3,5- dimethylbenzamide (1x).

Synthesized from 2, 3, 3,5-dimethylbenzoic acid (4b) and butyl isocyanide (5d) according to the general procedure. Colorless solid; yield 68%; mp 181 °C; tR:12.97 min, purity: 98.9%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 11.20 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.94–7.80 (m, 1H), 7.80–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.51–7.19 (m, 2H), 7.16–6.91 (m, 3H), 4.65/4.51* (2 x s, 2H), 3.89*/3.69 (2 x s, 2H), 3.16–2.95 (m, 2H), 2.27/2.24* (2 x s, 6H), 1.50–1.10 (m, 4H), 0.9–0.75 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.6, 167.6, 167.3, 164.0, 140.5, 140.3, 137.64, 137.6, 136.05, 135.9, 131.85, 131.7, 130.9, 127.7, 127.3, 127.15, 126.9, 124.1, 53.1, 51.0, 48.7, 47.3, 38.25, 31.25, 20.8, 19.6, 19.5, 13.7. Anal. Calcd. for C23H30N3O4: 412.2231 [M+H]+, Found: 412.2230.

4.2. Biological evaluation

4.2.1. P. falciparum asexual intraerythrocytic culture and growth inhibition assays.

P. falciparum drug-sensitive 3D7 [50] and multi-drug resistant Dd2 parasites [51] were cultured in vitro in O+ human erythrocytes in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated human serum and 5 µg/ml gentamycin (Sigma Aldrich, USA) . Cultures were maintained at 37oC in 5% O2 and 5% CO2 in N2 gas mixture. Asexual intraerythrocytic growth inhibition assays were performed using the [3H]-hypoxanthine uptake assays, essentially as previously described [28]. Briefly, ring-stage parasitized erythrocytes (0.25% parasitemia; 2.5% hematocrit) were incubated in dose response format with test compounds or controls. Percent inhibition of growth was compared to vehicle controls (0.5% DMSO) and 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) calculated using linear interpolation of inhibition curves. At least three independent assays were carried out, in triplicate wells, with data presented as mean IC50 (± standard deviation [SD]).

4.2.2. Protein hyperacetylation assays

Protein hyperacetylation assays were carried out essentially as previously described [18]. Briefly, synchronized trophozoite-stage P. falciparum 3D7 infected erythrocytes (3–5 % parasitemia, 5 % haematocrit) were incubated with 5x IC50 of test compounds or controls for 3 h. Control included a matched sample treated with vehicle only (0.18 % DMSO; 3h-C), the antimalarial drug chloroquine (CQ; 5x IC50) and the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat (SAHA; 5x IC50). Following treatment, cells were lysed in 0.15 % saponin, washed with 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove haemoglobin and the resulting parasite pellets resuspended in 1x SDS-PAGE loading dye. Heat denatured protein (93oC; 3min) was analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using PVDF membrane and anti-(tetra) acetyl histone H4 primary antibody (1:2000 dilution, Merck) in combination with IRDye 680 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution, Li-Cor Biosciences). Total protein load was assessed by staining PVDF membranes with REVERTTM Total Protein Stain (Li-Cor Biosciences), as per manufacturer’s instructions, prior to Western analysis. Membranes were imaged using an Odyssey Classic (Li-Cor Biosciences) and densitometry analysis carried out using Image Studio Lite Version 5.2 software. Western density signals were normalized to total protein load and expressed as fold change compared to the 3h-C DMSO vehicle control (taken as 1.0). Data are mean (±) SD for two independent experiments.

4.2.3. Gametocytocidal activity (Imaging based viability assay)

Highly synchronous gametocytes were prepared as published previously [44]. In brief a transgenic NF54-Pfs16-GFP parasite culture was, by the application of several conditions identified to stimulate gametocytogenesis, induced to produce gametocytes. After stimulation gametocytes were maintained in the presence of complete media, (5% serum (Sigma-Aldrich AU), 2.5mg/ml Albumax II (Invitrogen), 50µ g/ml hypoxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich), 10mM HEPES (Sigma- Aldrich) and 50mM N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (Sigma-Aldrich)) at 5% O2, 5% CO2, 21%N2.

The inhibition of gametocyte development from early stage I gametocytes to stage III gametocytes and stage IV to stage V gametocytes was performed as previously published [45]. Highly synchronized gametocytes at day 2 or day 8 of development, stage I or IV respectively, were isolated by magnetic column, adjusted to 10% gametocytes at 0.1%H in complete medium.Ten mM compounds stocks in DMSO were diluted in concentration response curves for determination of IC50 values. The stock compounds were diluted 1ul in a total of 25µ l of water and 5µl transferred into Poly-D-lysine coated 384 well CellCarrier plates (PerkinElmer). Forty- five microliters of stage specific gametocytes (I or IV) were then dispensed into the imaging plates. The plates were incubated under standard conditions for 72 hours before the addition of 5µl of MitoTracker Red CM-H2Xros (Invitrogen) followed by a further 16 hours incubation. The plates were then imaged on the OPERA confocal imaging system (PerkinElmer), and the number of gametocytes identified by their GFP morphology and MitoTracker Red CM-H2Xros viability signal enumerated. Inhibition of gametocyte development and loss of viability was normalized by representing all data as percent inhibition in relation to 0.4%DMSO and 5µM puromycin assay controls. The IC50 values were then calculated using Graphpad prizm 4 using non-linear regression, sigmoidal dose response (variable slope) with no constrains utilizing GraphPad Prizm 4.0.

4.2.4. Gametocytocidal activity (ATP bioluminescence assay)

The gametocytocidal activity against mature stage V gametocytes of the P. falciparum strain NF54 was evaluated by an ATP bioluminescence assay as described previously [52] with minor modifications [48]. Gametocyte culture was initiated from synchronized parasites in complete culture medium supplemented with 5% serum, starting with a 6% hematocrit level and a 0.3% parasitemia level. Culture medium was changed daily without parasite dilution throughout the entire process. When the parasitemia level reached 5%, the volume of the medium was doubled. Between days 12 to 15, the cultures were treated with 50 mM N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (MP Biomedicals GmbH) to remove the asexual stages, and on day 15 or 16, the culture was purified by a NycoPrep 1.077 cushion density gradient and magnetic column separation in order to remove uninfected erythrocytes and enrich the gametocyte population. All tested compounds were dissolved in DMSO before further dilutions with complete culture medium was done. After purification, mature gametocytes (50,000 per well) were incubated for 48 hours with the compound before performance of the ATP based luminescence assay. To assess the gametocytocidal activity of the compounds a pre-screening based on 2 concentrations (5 µM and 500 nM) together with the control compounds epoxomycin, methylene blue and chlorotonil A with known gametocytocidal activity was performed. Of the most promising compounds a 2-fold serial dilution was done to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) by analysing the nonlinear regression of log concentration–response curves using the drc-package v0.9.0 of R v2.6.1 [53].

4.2.5. Activity against P. berghei-Luc EFF and HepG2 viability (P. berghei-Luc Liver stage and HepG2 Cytotoxicity assays)

The liver stage activity against P. berghei-Luc (Pb-Luc) and toxicity to HepG2 cells were evaluated in Pb-Luc and HepG2 cytotoxicity bioluminescence assays as described previously [49] with minor modification as follows: HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP cells, stably transformed to express a GFP-tetraspanin receptor CD81 fusion protein, were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in culture media (DMEM with phenol red (Life Technology, CA), 10% FBS and 1x Pen Strep Glutamine (Life Technologies, CA)). For both, P. berghei-Luc and HepG2 cytotoxicity assays, 20–26 hour prior to Pb-Luc sporozoites infection, HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP20 cells at concentration 6×105 cells/mL in assay medium (DMEM without Phenol Red (Life Technologies, CA), 5% FBS, and 5x Pen Strep Glutamine (Life Technologies, CA)) were seeded in white solid bottom 1536-well plates (custom GNF mold ref# 789173-F, Greiner Bio-One) at volume 5 µ L per well (3×103 cells per well). Directly after that, 50 nL of compounds in 1:3 serial dilutions in DMSO (final DMSO concentration per well 0.5%) were transferred with Acoustic Transfer System (ATS) (Biosero) into the assay plates. Atovaquone (0.5 µ M) and Puromycin (10 µM) in 1:3 serial dilutions in DMSO were used as positive controls for Pb-Luc Liver Stage and HepG2 Cytotoxicity assays respectively. Wells containing 0.5% DMSO were used as negative control for the both assays. For Pb-Luc infection, P. berghei-ANKA-GFP-Luc-SMCON (Pb-Luc) [54] sporozoites were freshly isolated from infected Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes (received from Insectary Core Facility at New York University) as follows: Dissected salivary glands were homogenized in DMEM media (Life Technology, CA) using a glass tissue grinder and filtered twice through a 20 μM nylon net filter (Steriflip, Millipore). The sporozoites were counted using a Neubauer hemocytometer (C-Chip, InCyto, Republic of Korea), adjusted to final concentration of 200 sporozoites per 1µL in the assay media, and placed on ice until needed. To infect the HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP cells with Pb-Luc, 5 uL of the sporozoites suspension were added per well with a single tip Bottle Valve liquid handler (GNF) to a final number of 1,000 sporozoites per well. The assay plates were spun down at 37 °C for 3 minutes with a centrifugal force of 330xg on normal acceleration and brake setting. For the HepG2 Cytotoxicity assay, 5 uL per well of additional assay media (but not sporozoites) was added to the HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP cell to maintain equal concentrations of compounds with Pb-Luc infected plates. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h in 5% CO2 with high humidity to minimize media evaporation and edge effect. After the incubation, the EEF growth and HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP cells viability were assessed by a bioluminescence measurement as follows: Media was removed by spinning the inverted plates at 150xg for 30 seconds; 2 µL per well of BrightGlo (Promega) for quantification of Pb-Luc EEFs or CellTiterGlo (Promega) reagent (diluted 1:2 with deionized water) for quantification of HepG2-A16-CD81EGFP cell viability were dispensed with the MicroFlo (BioTek) liquid handler. Immediately after addition of the luminescence reagent, the luminescence was measured by the Envision Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer). For the data analysis, the background for the EEF inhibition was defined as the average of the five highest Atovaquone concentrations (20 wells), and the background for the HepG2 cytotoxicity was defined as the average of the 3 highest Puromycin concentrations (12 wells). IC50 values were determined using the average normalized bioluminescence intensity of 4 wells per concentration and plate (96 wells in total for each compound) and a nonlinear variable slope four-parameter regression curve fitting model in Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

4.2.6. In vitro testing on hHDAC1 and hHDAC6

The in vitro inhibitory activity of 1a, 1g, 1l, 1q, 1u, 1v and SAHA against two human HDAC isoforms (1 and 6) were measured using a previously published protocol [55]. OptiPlate-96 black microplates (Perkin Elmer) were used with an assay volume of 50 µ L. 5 µ L test compound or control, diluted in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA), were incubated with 35 µ L of the fluorogenic substrate ZMAL (Z- (Ac)Lys-AMC) [56] (21.43 µM in assay buffer) and 10 µ L of human recombinant HDAC1 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50051) or HDAC6 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50006) at 37 °C. After an incubation time of 90 min, 50 µ L of 0.4 mg/mL trypsin in trypsin buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) were added, followed by further incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm using a Fluoroskan Ascent microplate reader (Thermo Scientific). All compounds were evaluated in duplicate in at least two independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

➢ Novel HDACi were synthesized using a one-pot multi-component protocol

➢ All compounds showed nanomolar activity against asexual blood stage parasites

➢ Selected compounds were shown to hyperacetylate P. falciparum histones

➢ Compound 1u revealed potent and selective activity against exo-erythrocytic forms

➢ This series of HDACi represents a valuable starting point for further optimization

Acknowledgment

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is acknowledged for funds used to purchase the UHR-TOF maXis 4G, Bruker Daltonics, Bremen HRMS instrument used in this research. We acknowledge the Australian Red Cross Blood Service for the provision of human blood and sera for P. falciparum culture.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (HA 7783/1–1 to FKH and HE 7607/1–1 to JH), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1093378 and APP1074016 to KTA), the A-PARADDISE program funded under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (KTA) and a Griffith University Postdoctoral Fellowship (GMF). EAW and JA are supported by grants from the Medicines for Malaria Venture and NIH (5R01AI090141 and R01AI103058); VMA acknowledges the Australian Research Council (LP120200557) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture for their continued support.

Abbreviations

- EEF

exo-erythrocytic form

- Et3N

triethylamin

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitor h hour

- MeOH

methanol

- MS

molecular sieve

- SI

Selectivity Index (mammalian cell IC50/P. falciparum IC50)

- Pf

Plasmodium falciparum

- PfGAPDH

Plasmodium falciparum Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- PfESG

P. falciparum early stage gametocytes

- PfLSG

P. falciparum late stage gametocytes

- Pb

Plasmodium berghei

- RT

room temperature

- SAHA

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].World Health Organization, World Malaria Report 2017. WHO Press, Geneva: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [2].World Health Organization. Malaria vaccine: WHO position paper – January 2016, The Weekly Epidemiological Record (WER) 91 (2016) 33–52.26829826 [Google Scholar]

- [3].RTS S Clinical Trials Partnership. Efficacy and safety of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial, Lancet 386 (2015) 31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wells TN, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Van Voorhis WC, Malaria medicines: a glass half full? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 14 (2015) 424–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Anderson JM, Mao S, Sam B, Sopha C, Chuor CM, Nguon C, Sovannaroth S, Pukrittayakamee S, Jittamala P, Chotivanich K, Chutasmit K, Suchatsoonthorn C, Runcharoen R, Hien TT, Thuy-Nhien NT, Thanh NV, Phu NH, Htut Y, Han KT, Aye KH, Mokuolu OA, Olaosebikan RR, Folaranmi OO, Mayxay M, Khanthavong M, Hongvanthong B, Newton PN, Onyamboko MA, Fanello CI, Tshefu AK, Mishra N, Valecha N, Phyo AO, Nosten F, Yi P, Tripura R, Borrmann S, Bashraheil M, Peshu J, Faiz MA, Ghose A, Hossain MA, Samad R, Rahman MR, Hasan MM, Islam A, Miotto O, Amato R, MacInnis B, Stalker J, Kwiatkowski DP, Bozdech Z, Jeeyapant A, Cheah PY, Sakulthaew T, Chalk J, Intharabut B, Silamut K, Lee SJ, Vihokhern B, Kunasol C, Imwong M, Tarning J, Taylor WJ, Yeung S, Woodrow CJ, Flegg JA, Das D, Smith J, Venkatesan M, Plowe CV, Stepniewska K, Guerin PJ, M Dondorp A, Day NP, White NJ, Tracking Resistance to Artemisinin, C. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria, N. Engl. J. Med . 371 (2014) 411–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burrows JN, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Möhrle JJ, Oeuvray C, Wells TN, Designing the next generation of medicines for malaria control and eradication, Malar. J 12 (2013) 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burrows JN, Burlot E, Campo B, Cherbuin S, Jeanneret S, Leroy D, Spangenberg T, Waterson D, Wells TN, Willis P, Antimalarial drug discovery - the path towards eradication, Parasitology 141 (2014) 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Garnock-Jones KP, Panobinostat: first global approval. Drugs 75 (2015) 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Thompson CA, Belinostat approved for use in treating rare lymphoma, American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 71 (2014) 1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Prince HM, Dickinson M, Romidepsin for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Clin. Cancer Res 18 (2012) 3509–3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Grant S, Easley C, Kirkpatrick P, Vorinostat. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 6 (2007) 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Falkenberg KJ, Johnstone RW, Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 13 (2014) 673–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Witt O, Deubzer HE, Milde T, Oehme I, HDAC family: What are the cancer relevant targets? Cancer Lett 277 (2009) 8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Andrews KT, Haque A, Jones MK, HDAC inhibitors in parasitic diseases, Immunol. Cell Biol 90 (2012) 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Andrews KT, Tran TN, Fairlie DP, Towards histone deacetylase inhibitors as new antimalarial drugs, Curr. Pharm. Des 18 (2012) 3467–3479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Melesina J, Robaa D, Pierce RJ, Romier C, Sippl W, Homology modeling of parasite histone deacetylases to guide the structure-based design of selective inhibitors, J. Mol. Graph. Model 62 (2015) 342–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hailu GS, Robaa D, Forgione M, Sippl W, Rotili D, Mai A, Lysine Deacetylase Inhibitors in Parasites: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives. J. Med. Chem 60 (2017) 4780–4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Engel JA, Jones AJ, Avery VM, Sumanadasa SD, Ng SS, Fairlie DP, Adams TS, Andrews KT, Profiling the anti-protozoal activity of anti-cancer HDAC inhibitors against Plasmodium and Trypanosoma parasites, Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist 5 (2015) 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Andrews KT, Gupta AP, Tran TN, Fairlie DP, Gobert GN, Comparative gene expression profiling of P. falciparum malaria parasites exposed to three different histone deacetylase inhibitors, PLoS One 7 (2012) e31847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].New M, Olzscha H, La Thangue NB, HDAC inhibitor-based therapies: can we interpret the code? Mol. Oncol 6 (2012) 637–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tonkin CJ, Carret CK, Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Ralph SA, Hommel M, Duffy MF, Silva LM, Scherf A, Ivens A, Speed TP, Beeson JG, Cowman AF, Sir2 paralogues cooperate to regulate virulence genes and antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum, PLoS Biol 7 (2009) e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Freitas-Junior LH, Hernandez-Rivas R, Ralph SA, Montiel-Condado D, Ruvalcaba-Salazar OK, Rojas-Meza AP, Mancio-Silva L, Leal-Silvestre RJ, Gontijo AM,Shorte S, Scherf A, Telomeric heterochromatin propagation and histone acetylation control mutually exclusive expression of antigenic variation genes in malaria parasites, Cell 121 (2005) 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Marty AJ, Duffy MF, Good RT, Thompson JK, Freitas-Junior LH, Scherf A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF, Heterochromatin silencing and locus repositioning linked to regulation of virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum, Cell 121 (2005) 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Patel V, Mazitschek R, Coleman B, Nguyen C, Urgaonkar S, Cortese J, Barker RH,Greenberg E, Tang W, Bradner JE, Schreiber SL, Duraisingh MT, Wirth DF, Clardy J, Identification and Characterization of Small Molecule Inhibitors of a Class I Histone Deacetylase from Plasmodium falciparum, J. Med. Chem 52 (2009) 2185–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Joshi MB, Lin DT, Chiang PH, Goldman ND, Fujioka H, Aikawa M, Syin C, Molecular cloning and nuclear localization of a histone deacetylase homologue in Plasmodium falciparum, Mol. Biochem. Parasit 99 (1999) 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ontoria JM, Paonessa G, Ponzi S, Ferrigno F, Nizi E, Biancofiore I, Malancona S,Graziani R, Roberts D, Willis P, Bresciani A, Gennari N, Cecchetti O, Monteagudo E, Orsale MV, Veneziano M, Di Marco A, Cellucci A, Laufer R, Altamura S, Summa V, Harper S, Discovery of a Selective Series of Inhibitors of Plasmodium Falciparum HDACs, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 7 (2016) 454–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wheatley NC, Andrews KT, Tran TL, Lucke AJ, Reid RC, Fairlie DP, Antimalarial histone deacetylase inhibitors containing cinnamate or NSAID components, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 20 (2010) 7080–7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Andrews KT, Tran TN, Lucke AJ, Kahnberg P, Le GT, Boyle GM, Gardiner DL,Skinner-Adams TS, Fairlie DP, Potent antimalarial activity of histone deacetylase inhibitor analogues, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 52 (2008) 1454–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sumanadasa SD, Goodman CD, Lucke AJ, Skinner-Adams T, Sahama I, Haque A,Do TA, McFadden GI, Fairlie DP, Andrews KT, Antimalarial activity of the anticancer histone deacetylase inhibitor SB939, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 56 (2012) 3849–3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mukherjee P, Pradhan A, Shah F, Tekwani BL, Avery MA, Structural insights into the Plasmodium falciparum histone deacetylase 1 (PfHDAC-1): A novel target for the development of antimalarial therapy, Bioorg. Med. Chem 16 (2008) 5254–5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Darkin-Rattray SJ, Gurnett AM, Myers RW, Dulski PM, Crumley TM, Allocco JJ, Cannova C, Meinke PT, Colletti SL, Bednarek MA, Singh SB, Goetz MA, Dombrowski AW, Polishook JD, Schmatz DM, Apicidin: A novel antiprotozoal agent that inhibits parasite histone deacetylase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 (1996) 13143–13147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen Y, Lopez-Sanchez M, Savoy DN, Billadeau DD, Dow GS, Kozikowski AP, A Series of Potent and Selective, Triazolylphenyl-Based Histone Deacetylases Inhibitors with Activity against Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Plasmodium falciparum, J. Med. Chem 51 (2008) 3437–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dow GS, Chen Y, Andrews KT, Caridha D, Gerena L, Gettayacamin M, Johnson J,Li Q, Melendez V, Obaldia N 3rd, Tran TN, Kozikowski AP, Antimalarial activity of phenylthiazolyl-bearing hydroxamate-based histone deacetylase inhibitors, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 52 (2008) 3467–3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Agbor-Enoh S, Seudieu C, Davidson E, Dritschilo A, Jung M, Novel inhibitor of Plasmodium histone deacetylase that cures P. berghei-infected mice, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 53 (2009) 1727–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Marfurt J, Chalfein F, Prayoga P, Wabiser F, Kenangalem E, Piera KA, Fairlie DP,Tjitra E, Anstey NM, Andrews KT, Price RN, , Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 55 (2011) 961–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hansen FK, Sumanadasa SD, Stenzel K, Duffy S, Meister S, Marek L, Schmetter R,Kuna K, Hamacher A, Mordmuller B, Kassack MU, Winzeler EA, Avery VM, Andrews KT, Kurz T, Discovery of HDAC inhibitors with potent activity against multiple malaria parasite life cycle stages, Eur. J. Med. Chem 82 (2014) 204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stenzel K, Chua MJ, Duffy S, Antonova-Koch Y, Meister S, Hamacher A, Kassack MU, Winzeler EA, Avery VM, Kurz T, Andrews KT, Hansen FK, Design and Synthesis of Terephthalic Acid-Based Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors with Dual Stage Anti-Plasmodium Activity, ChemMedChem 12 (2017) 1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hansen FK, Skinner-Adams TS, Duffy S, Marek L, Sumanadasa SD, Kuna K, Held J, Avery VM, Andrews KT, Kurz T, Synthesis, antimalarial properties, and SAR studies of alkoxyurea-based HDAC inhibitors, ChemMedChem 9 (2014) 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Trenholme K, Marek L, Duffy S, Pradel G, Fisher G, Hansen FK, Skinner- Adams TS, Butterworth A, Julius Ngwa C, Moecking J, Goodman CD, McFadden GI, Sumanadasa SDM, Fairlie DP, Avery VM, Kurz T, Andrews KT, Lysine acetylation in sexual stage malaria parasites is a target for antimalarial small molecules, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58 (2014) 3666–3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kalin JH, Bergman JA, Development and therapeutic implications of selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors, J. Med. Chem 56 (2013) 6297–6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhang Y, Kwon S, Yamaguchi T, Cubizolles F, Rousseaux S, Kneissel M, Cao C, Li N, Cheng HL, Chua K, Lombard D, Mizeracki A, Matthias G, Alt FW, Khochbin S, Matthias P, Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally, Mol. Cell. Biol 28 (2008) 1688–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].De Vreese R, de Kock C, Smith PJ, Chibale K, D’hooghe M, Exploration of thiaheterocyclic hHDAC6 inhibitors as potential antiplasmodial agents, Future Med. Chem 9 (2017) 357–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Diedrich D, Hamacher A, Gertzen CGW, Alves Avelar LA, Reiss GJ, Kurz T, Gohlke H, Kassack MU, Hansen FK, Rational design and diversity-oriented synthesis of peptoid-based selective HDAC6 inhibitors, Chem. Commun 52 (2016) 3219–3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Duffy S, Loganathan S, Holleran JP, Avery VM, Large-scale production of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes for malaria drug discovery, Nat. Protoc 11 (2016) 976–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Duffy S, Avery VM, Identification of inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes development, Malar. J 12 (2013) 408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]