Abstract

This paper compares the policy trajectories of Nutrition and Early Childhood Development (ECD) in Pakistan, identifying enablers that led to better multisector progress for Nutrition over ECD. Specifically, it deliberates on (1) multisector policy adoption in terms of instigation, construct and stakeholder coalitions; and (2) horizontal coordination in terms of capacity, incentives and structures. The analysis builds on existing work of the authors, supplementing this with further document review and expert insights. Nutrition and ECD initiatives in Pakistan, while overlapping agendas, differed in terms of buy-in and structural grounding. A favourable policy window for Nutrition was successfully managed through coordinated advocacy, programmatic support and investment in networks, while capture of policy opportunities was not seen in case of ECD. A vague construct for ECD confined its activities narrowly to the education sector while a Nutrition discourse specifying roles for other sectors resulted in a broader coalition and expanded activities. Both Nutrition and ECD faced powerful disincentives to coordination, but Nutrition overcame this through cofinancing of different sectors and creation of structural platform in supraplanning ministries. Both Nutrition and ECD share common capacity constraints for horizontal coordination, raising concerns for effective implementation. We conclude that multisector action for child well-being requires deliberative action and investment to unlock opportunities. The analysis from Pakistan highlights four governance areas for progressing multisector action: (1) opportune management of policy windows; (2) a clear and inclusive menu of actions for stakeholder coalitions; (3) availability of cofinancing and structural platforms for catalysing coordination; and (4) investment in horizontally placed human resource and integrated tracking systems.

Keywords: nutrition, child health, health policies and all other topics

Summary box.

Multisector action is prominent in current global discourse for child’s well-being, but there is a search for policy lessons on how an enabling environment for multisector action can be created.

Nutrition, in comparison to Early Childhood Development (ECD), had better multisector buy-in, planning and structural platforms for multisector governance.

Management of a favourable policy window, a crisp and inclusive action agenda, coordinated advocacy, and catalytic cofinancing created an enabling environment for multisector Nutrition but similar efforts were missing for ECD.

Both Nutrition and ECD are faced with weak coordination for multisector implementation.

Implementation coordination requires dedicated investment to overcome inherent disincentives to multisector working.

A different set of capabilities is required for implementation coordination involving horizontally placed human resource, and integrated resource tracking, planning and monitoring systems.

Introduction

Child health and well-being interventions such as Nutrition and Early Childhood Development (ECD) are reliant on multiple sectors such as Health, Nutrition, Social Protection, Education, Food Security and WASH for effective execution. Globally, a favourable political environment now exists for undertaking multisector work for child well-being. The United Nations (UN) has also called on governments to ‘strengthen governance and political commitment,’ for Nutrition and ECD1 but search is under way on lessons for multisector policies and their effective programming.2 3

Under-Nutrition contributes to stunted child growth, impaired cognitive development and preventable mortality. The first 1000 days of life from pregnancy to a child’s second birthday are critical, with important opportunities up to 5 years of age for reducing undernutrition.4 ECD has a broader mandate entailing social, cognitive and physical development from pregnancy, birth to a child’s first 8 years of life.5 Both share underlying determinants of access to healthcare, adequate dietary intake, water-sanitation-hygiene (WASH) and social protection, while ECD additionally involves cognitive stimulation provided by family support, preschool and primary education. Globally, a quarter of children under 5 years of experience are stunted for growth6 and 36.8% do not reach fundamental cognitive and socioemotional milestones.7

Nutrition has generated unprecedented policy dialogue over the last 6 years with a proliferation in global funding initiatives on Nutrition,8 and coordinated donor-government-civil society commitment through the global Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement.9 10 On the other hand, ECD has been around much longer as a policy issue, with efforts speared by the World Bank in the 1990s but largely embedded in education programmes.11 Services globally remain fragmented, of variable quality and not implemented at scale.3 11 The Lancet Series on Maternal and Child Nutrition 2013 and the Lancet Early Childhood Development Series of 201612 both emphasise interconnections required across sectors. However, despite much policy discourse on the need for multisector tackling of Nutrition and ECD, there is a search for lessons on how best to bring about multisector governance for child well-being initiatives. World Bank13 defines governance as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised. Extension to collaborative governance is more challenging, less well understood and can benefit from further insights on political economy and public administration. ECD research has remained largely interventional while Nutrition has drawn more multisector governance focused evidence in recent years on explaining commitments, collaborations and capacities.14–16

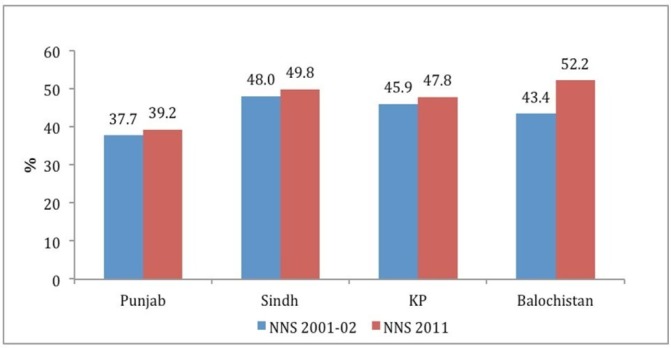

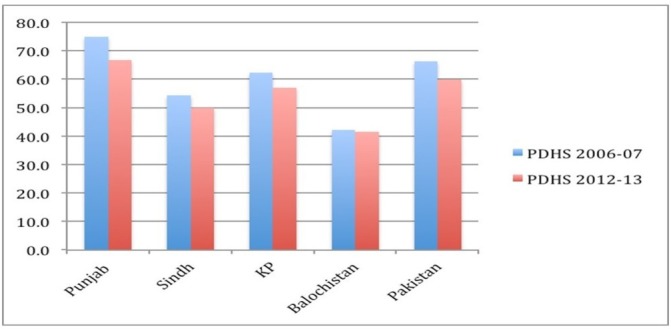

This paper tracks Nutrition and ECD initiatives in Pakistan highlighting key enablers and constraints for multisector working. Pakistan is a signatory to the 1990 UN Convention on Rights of the Child17 mainly implemented through initiatives in Health and Education sector. Multisector working for child well-being had however not been on the policy agenda until recently. In Pakistan, 45% of children under 5 are stunted18 (figure 1) and net primary school enrolment is only 57%19 with little improvement over the last decade (figure 2). Although historically governed by a strong federating structure, in 2011 major devolution reforms changed the balance of authority with 21 subjects, including Health, Education and other social sector subjects, devolved to provinces for full policy, fiscal and operational responsibility.20 This has provided an opportunity for more manageable multisector coordination for child health at the subnational level and speedier translation into implementation.21 At the same time, devolution also introduced challenges of varying priority for child well-being initiatives across different provinces.

Figure 1.

Stunting Trend Across Provinces: National Nutrition Survey (NNS).

Figure 2.

Net Primary School Enrollment Trend across Provinces: Pakistan Demographic & Health Survey (PDHS).

We track the roll-out of Nutrition and ECD initiatives, comparing the policy trajectories in terms of multisector adoption and horizontal governance across sectors. Given that both Nutrition and ECD are under implementation in Pakistan, the analysis is confined to multisector adoption and early implementation, and does not measure implementation outcomes. Importance of defined leadership, multisector structural platforms and horizontal working capacity has been illustrated in existing literature.15 22 Our analysis builds on this and further incorporates issue construct and policy instigation, incentives and disincentives for multisector working. Hence, this paper tracks Nutrition and ECD trajectories in three areas: (1) how the construct and policy instigation of the issue lends itself to multisector working; (2) stakeholders’ coalition in terms of breadth of stakeholders involved and defined leadership; and (3) horizontal coordination in terms of multisector platforms, incentives and capacities for horizontal working across different government ministries.

The analysis draws on the Nutrition Political Economy Analysis (PEA)23 Pakistan conducted over 2012–2013 and the landscape analysis on Preventing Undernutrition through Multisector Interventions (PUTMI).24 PEA involved interaction with Education, Health, WASH, Agriculture, Food, Local Government, Women’s Empowerment, Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), Social Protection, Planning and Development, Donor and UN agencies, experts and non-governmental organisations (NGO) through 84 informed consent interviews. Both PEA and PUTMI undertook desk review government strategies, plans and project proposals, budgetary outlay, notifications of multisector committees, donor nutrition investment strategies, project assessment reports, and so on. These two bodies of work drew in findings related to Nutrition as well as the interconnected area of ECD. These are supplemented with information from policy round tables and desk review for ECD and Nutrition over 2016 and 2017. A non-systematic scoping review was done of published online literature on Google Scholar, Medline, Popline and Google. Additionally, a website search of relevant government ministries, donor agencies and large NGOs was done for ECD and Nutrition initiatives.

Issue interpretation and instigation

Early Childhood Development

The instigation for ECD initially came in the late 1990s by the Aga Khan Development Network’s investment in human resource development and evidence generation. Soon after exploratory discussions were held by aid agencies such as the ADB with the federal government but found a lukewarm response.25 Policy window in late 1990s was clearly favourable due to an emphasis by the military supported technocratic government on ‘modern enlightenment’ and human development.26 A National Commission of Human Development (NCHD) had been set up for housing special initiatives.27 However, the vague menu of action for ECD28 constrained its buying in within the NCHD and relevant ministries. Some governmental buy-in was instead realised for the Early Childhood Education (ECE) component of the larger ECD agenda. ECE was easily quantifiable as separate ‘katchi’ or preschool classes, supported by teacher training and parental involvement. The Dakar Framework for Action (2000) on ECE provided a further impetus for ECE. Hence found ready support from educationists within the technocratic government, as well as from NGOs and resource institutions.29 Similarly, within aid agencies working in Pakistan, ECD was confined to ECE and left in the ambit of the education teams. Education advisors within aid agencies shied away from the larger ECD agenda for fear it could be vulnerable to domination by their health counterparts.

ECE became incorporated in Pakistan’s National Education Policy 1998–2010, recognising ‘katchi’ or preprimary as a formal class in primary schools.30 ECE was also incorporated in the National Plan of Action for Education 2001–2015 providing a plan of ECE provision to at least 50% of the population by 2015.31 This was followed in 2002 by the development of a National ECE curriculum32 assisted by educationists and resource institutions (box 1).

Box 1. ECE policy initistiatives Pakistan.

National Education Policy (1998–2010)

Recognition of katchi/preprimary class as part of primary schooling

National Plan of Action (2001–2015)

Education for all long-term framework introduces ECD as one of its three areas of focus

National ECE Curriculum (2002)

Curriculum developed with participation of government, academic and resource agencies, updated 2007

ECE Innovative Program (2001–2004)

ECE classes in selected schools by provincial Education Reform Units funded by federal Education Ministry, with largest roll-out in Punjab

Resource Institutions and NGO Projects (2002–2009)

Realising Confidence and Creativity by Aga Khan Foundation in Sindh, Baluchistan, KP, Northern Areas.

Interactive Teaching by Children’s Global Network in Punjab.

Child Friendly Schools Programme by Children’s Resources International in Islamabad.

Early Learning Program by Sindh Education Foundation in seven districts of Sindh.

ECCD Program by Plan International in selected Punjab districts.

Training/learning materials by Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi and Teacher Resource Centre in focal districts.

Post devolution

Provincial Education Sector Strategies (2012–2018) incorporate ECD as part of primary education in all schools.

Provincial funding provided for ECD classes, materials, training roll-out.

ECD incorporated into multisector nutrition programming in Sindh and Punjab.

Notification of National Task Force on ECD operated within National Nutrition Cell of Planning Commission.

ECD, Early Childhood Development; ECCD, Early Childhood Care and Development; ECE, Early Childhood Education; NGO, non-governmental organisation.

ECE implementation was not at scale and involved NGO projects in focal districts supported by development agencies, Unicef or philanthropies but with weakly standardised activities33 (box 1). Government implementation was planned for 2002–2005 as innovation in selected districts, but could not meaningfully take off because provinces showed little interest and failed to put up the cofinancing share to match federal Education Ministry’s allocation.34 After passage of provincial devolution in 2011, all four provinces have incorporated ECE in the provincial education sector strategies and earmarked budgets for ECE classrooms, training and teachers’ salaries.35–38 However, schemes have been slow moving and ECE services are confined to some but not all public primary schools. Very recently, in 2017, ECD has been incorporated as part of national Nutrition programming efforts. An ECD Task Force has been notified by the Nutrition Section of the National Planning Commission and two of the larger provinces of Punjab and Sindh have incorporated ECD as part of their nutrition planning and budgets.39 Hence, the broader ECD agenda has become nested within the relatively smaller scoped agenda of Nutrition.

Nutrition

Nutrition historically had parallel activities in both the Health and Food Security sectors. Nutrition was raised as a health issue during the 1990s, focusing on breast feeding promotion through baby friendly hospitals and supported by a network of paediatricians and the Unicef.40 By early 2000s, activities expanded to include salt iodisation, micronutrient implementation studies and Community Manangement of Acute Malnutrition t41 (box 2). Funding was small scaled, short term, largely uncoordinated and routed mainly through UN agencies and Intrenational non-government organizations (INGOs).21 In 2005, a Nutrition Wing was established in the Federal Ministry of Health (MoH) to support micronutrient supplementation projects. On a parallel footing, economists and planners within the government have historically associated Nutrition with ‘Hunger’ with a primary focus on sufficient wheat production and market supply.42 In addition, from time to time there have been schemes popular with political representatives, for free or subsidised provision of food commodities, such as ‘ration stores’ for subsidised food supplies in cities, wheat flour bags distribution in disaster affected regions, ‘Sasti roti’ and ‘sarkari kitchen’ schemes to supply prepared food at low cost (box 2).23 Political support for hunger alleviation supported establishment of a National Food Security Task Force in 2008, followed by a National Ministry of Food Security in 2012 and a National Zero Hunger Plan in 2012.43

Box 2. Nutrition policy inititaives Pakistan.

Health initiatives: 1990-2000

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative by Paediatricians and Unicef.

Edible oil incentives for pregnancy check-ups by World Food Program.

Nutrition Wing in Ministry of Health.

Vitamin A supplementation introduced in Polio Immunisation Campaigns.

Iodised Salt introduction by INGOs and MoH.

Sprinkles and other micronutrient supplementation pilots—MoH, INGOs, academia.

Food Security Initiatives: 1990s–2000s

Wheat supply index monitoring.

Wheat bags distribution by politicians in constituencies during disasters.

Ration stores in urban centres and ‘sasti roti’ scheme in Lahore by local government.

Charity kitchens by philanthropic outfits in Karachi and major cities.

Tawana Pakistan girl child feeding project in schools by Ministry of Social Welfare.

2010 onwards

CMAM for flood affectees by United Nations (UN) agencies.

Intersectoral Nutrition Strategies in all provinces.

National Zero Hunger Program by Ministry of Food Security.

Establishment of ‘Food Regulatory Authority’ in Punjab and Sindh.

Nutrition projects under way in provincial Health funded by World Bank.

Fortified edible oil and wheat flour project under way funded by Department For International Development, UK.

Instigation for a multisector construct to Nutrition came from a combination of global and local events during the period 2011–2012. At the global level, the SUN movement profiled Nutrition as a development rather than health agenda and an emergency for immediate action, managing to successfully mobilise donor aid support to countries such as Pakistan having a high burden of Under-Nutrition. At the same time, the publishing of the Lancet Series on Nutrition in 2008 and then 2013 provided cost-effective interventions, well advocated by development partners to policy circles in Pakistan.21 These coincided with local events in Pakistan. The widespread floods of 2010 and 2011 further served to highlight malnutrition in flood affectees to the general public—hence nutrition suddenly became visible.44 This was closely followed by the launch of the National Nutrition Survey (2011) providing dismal country and provincial statistics. These events were well advocated by development partners to the media, politicians and senior bureaucracy, using local experts and paediatricians as powerful advocates.

Consequently, Pakistan became a signatory to the SUN movement in 2012.45 Intersectoral Nutrition Strategies were developed over 2013 by all four provinces. At least three provincial governments are in process of programming and funding stunting reduction programmes in the sectors of Health, WASH, Food, Agriculture and Education.46 The momentum has already started in the Health sector with nutrition projects on ground across all four provinces, funded by the World Bank and partially cofinanced by provincial governments.47–50

Leadership and policy coalitions

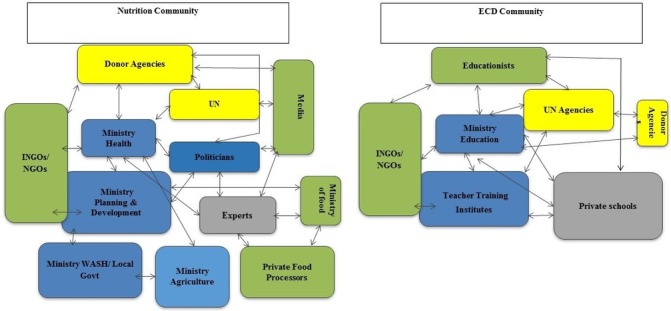

ECD and Nutrition, despite their overlapping agendas, have largely separate policy coalitions (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stakeholder Communities for Nutrition and ECD

ECD, brought forward as an education programming issue in Pakistan, had a small coalition confined to the education sector. Leadership for the ECD agenda kept on shifting from educationists to the federal government to more recently the provincial governments. Well-known educationists from civil society and academic institutions formed linkages with educationists in the federal government towards ECE, although these linkages later weakened with movement out of educationists from the federal government. Development partners have provided piecemeal funding through local NGOs, semigovernment agencies and recently through international NGOs.33 Local researchers investigating ECD interventions found positive development changes through ECD interventions but no impact on physical growth. Neither ECE nor the larger ECD agenda was well advocated to political and bureaucratic leadership nor to district and local governments.28 Private schools in major cities of Pakistan provide ECE as part of an integrated curriculum but cater to the higher income groups and lack regulation by government.51 Despite an active media presence in Pakistan, ECE has not been effectively advocated to the media.

In the case of Nutrition, the coalition comprised mainly paediatricians, hunger-related proponents and UN agencies, but from 2011 onwards expanded to a wider coalition involving stakeholders across Health, WASH, Food Fortification, Agriculture and Community Development sectors.23 Development partners provide the major thrust for policy dialogue, programming and implementation. The World Bank president has declared Nutrition as an emergency for accelerated investment in Pakistan,52 a multidonor nutrition group has been established and significant funding contributed by the bilateral and multilateral agencies,53–55 Unicef and World Food Program.56 57 With growth in international aid, an increasing number of international NGOs and local NGOs have also expanded operations into the Nutrition.46 On the government front, Nutrition dialogue is now steered at the highest administrative level with the National Planning Commission and its counterpart provincial Planning and Development Departments (P&DD) are the designated nutrition multisector hubs. Nutrition projects have been started within all provincial Health Ministries47–50 and to varying extent within other provincial ministries of Population Welfare, WASH, Agriculture, Livestock and Education. Nutrition has also managed to get support from the political legislature with mention in electoral manifestos of most major political parties,58–61 an active nutrition caucus of legislators has been formed in the provincial assembly of Punjab, and visible ownership provided by the Chief Minister in Sindh. The print and electronic media continues to provide Under-Nutrition public limelight, placing it centrally within policy debate. Private market suppliers have been drawn in for food fortification activities although the private market for WASH, Health, Agriculture and Livestock, and so on is yet to be effectively mobilised. Importantly, earmarked funding for SUN networks provided by UN agencies has catalysed interaction and exchange between business sector, NGOs, research entities and the government.

However, both Nutrition and ECD coalitions have failed to mobilise the Social Protection sector, despite Pakistan having a large national cash transfer programme targeting low-income women. Similarly, both Nutrition and ECD lack political champions to oversee implementation. Nutrition has had relative success with political championing in one province.

Horizontal coordination

Both Nutrition and ECD in Pakistan have weak coordination for multisector implementation.

Structural platforms

At the national level, the Planning Commission has a demarcated Nutrition section that serves to coordinate nutrition as a subject and serves as the secretariat for the SUN network. A multisector committee for ECD has been recently set up under the Nutrition section of the Planning Commission with a purpose to support the national nutrition targets. Provinces are the main hubs for planning, programming, funding and monitoring child’s well-being initiatives in decentralised Pakistan. Nutrition planning, resourcing and oversight are being coordinated by the provincial P&DDs in each province.24 This is significant as the P&DD is the overarching department for approval of projects across different ministries. ECD does not have a coordination platform in the provincial P&DDs. District governments run by District Commissioner Offices are the natural implementation points to coordinate and monitor activities across the different sectors of Health, Education, WASH, Food, Agriculture, and so on. However, as yet there has been no move to create district-level platforms for either Nutrition or ECD. Local union council structures remain rudimentary and have not been administratively empowered for the delivery of social sector services beyond few services of WASH.62

Incentives and disincentives to coordinate

There are powerful structural disincentives for coordination presented by separate leadership, human resources and supply chains of different government departments.23 Nutrition, in contrast to ECD, has been able to get funded programmes in different provincial ministries of Health, WASH, Agriculture, Livestock, Population Welfare and Education in at least three provinces and an integrated stunting plan in place in two provinces. ECD has found recognition in education reform projects in the provinces but programming within Health, WASH and Social Protection sectors has not happened.

Donor financing and steering by nutrition champions within P&DDs have been powerful incentives for proliferation of nutrition projects across sectors in provinces where progression has been seen.24 However, these ongoing multisector efforts are geared towards functional coordination through more integrated planning and there is reluctance of government ministries to share existing resources as well as competition for new funding.23 With separate government ministries managing nutrition projects, there is danger of discoordination during implementation in terms of geographies, timelines and vertical service delivery channels. At the same time, Health and Education provincial ministries continue to exert a powerful traction on Nutrition and ECD initiatives, respectively. Prior experience, comparatively skilled human resource, as well as being responsible for nutritional anthropometric measurement and primary school enrolment have provided Health and Education a visible domination over other relevant departments.

Capacity for coordination

Horizontal coordination capacity remains weak for both ECD and Nutrition. Although Nutrition is steered by the provincial P&DDs, it is only in two provinces that a dedicated Nutrition cell supported by staff has been created and has successfully resulted in funded nutrition projects across multiple ministries. In the other two provinces, Nutrition is managed by the Health section of P&DDs and programming has remained slow due to lack of legitimacy of the Health section to effectively steer other sections as well as dedicated staff time to oversee Nutrition activities. All P&DDs lack a system for integrated resource tracking across sectors and have become particularly challenging with growth in the number of international donors, UN agencies and INGOs providing support.24 Similarly, lack of target setting for each of the relevant ministries and absence of an integrated performance tracking systems blunts effective overseeing of Nutrition and ECD initiatives. There are also unmet capacity gaps within the vertical ministries. Ministries other than Health and Education lack area specialists for ECD and Nutrition constraining what to programme and monitor. Furthermore, all relevant ministries including Health and Education lack regulatory capacity to mainstream Nutrition and ECD across public and private providers.

Conclusion

The overlapping agendas of Nutrition and ECD initiatives in Pakistan differed in terms of multisector buy-in and structural grounding; however, both face common capacity constraints for multisector implementation. We come across four areas to be of relevance for creating an enabling environment, as discussed below.

First, experience from Pakistan shows that coordinated management of policy events is required to get multisector political commitment, taking advantage of windows of opportunity. In the case of Nutrition in Pakistan, a donor wave of funding, well-planned evidence-based advocacy and local floods helped in opening a window of opportunity for multisector commitment. ECD, in contrast, grappled to find political commitment as a multisector agenda, remaining confined to the Education sector and small-scale delivery. In the case of ECD, insufficient donor mobilisation and less tangible visibility compared with Nutrition blunted the possibility of larger political buy-in.

Second, we found that issue construction (particularly in terms of incentives for other sectors) was key to shaping ownership. In Pakistan, the vague construct of ECD and lack of a crisp menu of actions beyond Education resulted in a narrow coalition. Low policymaker unawareness for ECD is a commonly faced issue in South Asia and has proved detrimental for mobilising funding.63 Nutrition was successful in getting a coalition representing different sectors in Pakistan, helped along by deliberative investment in multisector networking. Lack of clarity on role of sectors can result in slow policy translation.

The need for an identified champion for multisector agendas has been advocated by international experts.64 In Pakistan, ECD lacked a champion due to being poorly understood while Nutrition, despite garnering political commitment, failed to come up with a defined leadership which has slowed implementation. Experience from Uganda similarly shows widening coalitions but lack of national champions such as celebrities and parliamentarians with whom the public can identify.65

Third, incentives and disincentives for coordination need to be recognised and addressed. In Pakistan, Health and Education sectors continued to exert powerful influence over Under-Nutrition and ECD undermining participation of other sectors. In the case of Nutrition, this was overcome through a structural platform in national and subnational planning ministries and donor cofinancing of programmatic activities in nutrition sensitive sectors. Structural platforms are not commonly found for ECD even in countries of high commitment such as Columbia66 but are increasingly seen for Nutrition as in Peru67 and certain African countries. There is comparatively less known on what makes them work.

Lastly, horizontal coordination cannot happen effortlessly and has its distinctive capacity needs. These included designated staff for coordination, systems for integrated planning, resource tracking and performance tracking across sectors, district platforms, and placement of subject specialists within key supporting ministries to help them programme for Nutrition and ECD.

In conclusion, multisector action for child well-being requires deliberative action and investment to unlock opportunities. Our findings from Pakistan highlight three governance areas that helped progress Nutrition as a multisector agenda and can be applied to ECD: (1) opportune management of policy windows; (2) a clear and inclusive menu of actions for stakeholder coalitions; and (3) availability of cofinancing and structural platforms for catalysing coordination. A common gap across both Nutrition and ECD is weak coordination capacity and requires investment in horizontally placed human resource, district coordination platforms and integrated systems for planning, resourcing and performance tracking.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: SAZ and KR conceptualised the framing of the paper. SAZ and ZB undertook the analysis assisted by SSH. SAZ wrote the paper, while review and inputs were made by ZB, SSH and KR. SAZ and ZB respectively led the PEA and PUTMI works, SSH assisted with additional documentary review and stakeholder discussions, SAZ and KR conceptualised the paper with review by ZB.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. WHO. Global nutrition policy review: what does it take to scale up nutrition action? 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gillespie S, Haddad L, Mannar V, et al. . The politics of reducing malnutrition: building commitment and accelerating progress. Lancet 2013;382:552–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60842-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daelmans B, Darmstadt GL, Lombardi J, et al. . Early childhood development: the foundation of sustainable development. The Lancet 2017;389:9–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31659-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, et al. . Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:60–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. . Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet 2017;389:77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, et al. . Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382:427–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCoy DC, Peet ED, Ezzati M, et al. . Early childhood developmental status in low- and middle-income countries: national, regional, and global prevalence estimates using predictive modeling. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002034 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. IFPRI. Global nutrition report: actions and accountability to accelerate the world’s progress on nutrition. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. SUN. Scaling up nutrition movement progress report: SUN Movement Secretariat, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. Report of the commission on ending childhood obesity: implementation plan. 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259349/1/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf

- 11. Young ME, Richardson LM. Early child development; from measurement to action. The World Bank Washington, DC. 2007. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/6837/409250PAPER0Ea101OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY1.pdf;sequence=1

- 12. Menu ENN, Exchange F. Advancing early childhood development: from science to Scale, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67. World Bank. Governance and Development. Washington DC: The World Bank, 1992. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/604951468739447676/Governance-and-development [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lamstein S, Pomeroy-Stevens A, Webb P, et al. . Optimizing the multisectoral nutrition policy cycle: a systems perspective. Food Nutr Bull 2016;37(4 suppl):S107–S14. 10.1177/0379572116675994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Acosta MA, Fanzo J. Effective governance and policies to improve nutrition outcomes: a cross comparison of nine country cases. Ann Nutr Metab 2013;63:854. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoey L, Pelletier DL. Bolivia’s multisectoral Zero Malnutrition Program: insights on commitment, collaboration, and capacities. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32(2 Suppl):S70–S81. 10.1177/15648265110322S204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. UN. Convention on the rights of the child. Washington DC, USA: United Nations, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. GoP. National nutrition survey. Planning and development division, government of Pakistan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. GoP. Pakistan social and living standards measurement survey Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Islamabad 2016:2014–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20. GoP. 18th amendment report national assembly of Pakistan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaidi S, Mohmand SK, Hayat N, et al. . Nutrition policy in the post-devolution context in Pakistan: an analysis of provincial opportunities and barriers*. IDS Bull 2013;44:86–93. 10.1111/1759-5436.12035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pelletier D, Gervais S, Hafeez-Ur-Rehman H, et al. . Boundary-spanning actors in complex adaptive governance systems: the case of multisectoral nutrition. Int J Health Plann Manage 2018;33:e293–e319. 10.1002/hpm.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaidi S, Bhutta ZA, Mohmand SK, et al. . The political economy of undernutrition national report: Pakistan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heart. Preventing undernutrition through multi-sectoral initiatives in pakistan; a landscape analysis, Washington, DC 20001 USA. 2015. http://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/PUTMI-Landscape-Report-FINAL_31-07-2015.pdf

- 25. Ahmad M. Early childhood education in Pakistan: an international slogan waiting for national attention. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 2011;12:86–93. 10.2304/ciec.2011.12.1.86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. TALBOT IAN. General Pervez Musharraf: Saviour or destroyer of Pakistan’s democracy? Contemp South Asia 2002;11:311–28. 10.1080/0958493032000057726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Commission for Human Development. Let’s join hands to promote quality education in Pakistan. 2013. http://www.nchd.org.pk/ws/documents/2013.pdf

- 28. Rich-Orloff W, Khan J, Juma A. Early childhood education in Pakistan: evaluation report of USAID’s supported programs, devtech systems, Inc. 2007. https://usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdack938.pdf

- 29. Hunzai ZN. Early years education in Pakistan: trends, issues and strategies. Int J Early Years Educ 2007;15:297–309. 10.1080/09669760701516975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministry of Education, Pakistan. National education policy (1998-2010). http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/APCITY/UNPAN014613.pdf

- 31. Ministry of Education. National report on the development of education: Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan. 2008. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/National_Reports/ICE_2008/pakistan_NR08.pdf

- 32. Ministry of Education. National curriculum: early childhood education. Ministry of Education (Curriculum Wing) Islamabad, Pakistan. 2002. http://aserpakistan.org/document/learning_resources/2014/Early_Childhood_Education/ECE.pdf

- 33. Khan F, Ali AG, Kabani A. Early childhood development initiatives in Pakistan: a mapping study. Sindh Education Foundation. 2010. http://www.sef.org.pk/images/publications/ECD-mappingstudy/ecd-mapping-study.pdf

- 34. Ministry of Education. ECE policy review: policies, profile and programs of Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Pakistan. Federal Ministry of Education and Children’s Resources, International. 2008. http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/appeal/ECCE/reports_and_publications/Final_Policy_Review_Report-_ECCE_pakistan.pdf

- 35. Government of Sindh. Sindh education sector plan: 2013 – 2016. 2013. http://www.aserpakistan.org/document/learning_resources/2014/Sector_Plans/SindhSectorPlan2013-2016.pdf

- 36. Government of Punjab. Punjab School Education Sector Plan: 2013-2017. 2013. http://aserpakistan.org/document/learning_resources/2014/Sector_Plans/PunjabSectorPlan2013-2017.pdf

- 37. Government of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa. Education Sector Plan: 2010-2015. Elementary and Secondary Education Department 2012. http://itacec.org/document/sector_plans/ECEinPakistanProvincialSectorPlans.pdf

- 38. Government of Baluchistan. Balochistan education sector plan: 2013-2018. Policy planning and implementation unit 2013. http://emis.gob.pk/Uploads/BalochistanEducationSectorPlan.pdf

- 39. Government of Sindh. Sindh accelerated action plan for reduction of stunting and malnutrition: sehatmand sindh: Planning & Development (Nutrition section), Government of Sindh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khan M, Akram DS. Effects of baby-friendly hospital initiative on breast-feeding practices in sindh. J Pak Med Assoc 2013;63:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Technical Resource Facility. Nutrition mapping and proposing options for scale up in Pakistan 2012. http://www.trfpakistan.org/Portals/18/TRFreports/MNCH/Nutritionmappingandoptionsforscaleup2012.pdf?ver=2017-03-22-181031-467

- 42. World Food Programme. Pakistan food security bulletin. vulnerability analysis and mapping. United Nations. 2015;3 http://vam.wfp.org.pk/Publication/PFSB_August_2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Actions for Zero Hunger. Office of the special representative of secretary general - food security & nutrition. 2015. http://www.un.org/en/zerohunger/pdfs/ZeroHungercountryactionsDec_2015.pdf

- 44. Hossain SMM, Talat M, Boyd E, et al. . Evaluation of Nutrition Surveys in Flood-affected Areas of Pakistan: Seeing the Unseen!. IDS Bull 2013;44:10–20. 10.1111/1759-5436.12026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scaling Up Nutrition Movement. Declaration of commitments on the launch of scaling up nutrition movement in pakistan. pearl continental Hotel, Bhurban, Pakistan. 2013. http://scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Pakistan-SUN-Launch-Declaration.pdf

- 46. Department for International Development. Preventing under nutrition through multi-sectoral initiatives in Pakistan: a landscape analysis. 2015. http://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/PUTMI-Landscape-Report-FINAL_31-07-2015.pdf

- 47. Government of Baluchistan. PC-1: nutrition programme for baluchistan. Nutrition Programme Baluchistan: Health Department, Government of Baluchistan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. PC-1: nutrition programme for KPK: Nutrition Programme KPK, Health Department, Government of KPK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Government of Punjab. PC-1: nutrition programme for Punjab: Nutrition Programme Punjab, Health Department, Government of Punjab, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Government of Sindh. PC-1: nutrition programme for Sindh: Nutrition Programme Sindh, Health Department, Government of Sindh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ministry of Education. National report on the development of education: pakistan ministry of education Islamabad, Pakistan. 2008. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/National_Reports/ICE_2008/pakistan_NR08.pdf

- 52. Business Recorder. Stunting: a national emergency. 2016. http://epaper.brecorder.com/2016/10/10/2-page/801658-news.html

- 53. DFID’s Contribution to Improving Nutrition. Independent commission for aid impact 2014 (36). https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/ICAI-REPORT-DFIDs-Contribution-to-Improving-Nutrition.pdf

- 54. The World Bank. Pakistan development update: making growth matter The World Bank 2016. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/935241478612633044/pdf/109961-WP-PUBLIC-disclosed-11-9-16-5-pm-Pakistan-Development-Update-Fall-2016-with-compressed-pics.pdf

- 55. European Union. Action document for "Programme for Improved Nutrition in Sindh (PINS)". 2016(2016/038-937). https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/aap-financing-pakistan-annex4-c_2016_8487_en.pdf

- 56. United Nations Children’s Fund. Pakistan annual report, Pakistan. 2015. https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/FINAL_UNICEF_Annual_Report_2015_.pdf

- 57. World Food Programme. Fighting hunger worldwide: the world food programme’s year in review. 2010. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp236112.pdf

- 58. Pakistan Muslim League (N). National agenda for real change, manefesto. 2013. http://pmo.gov.pk/documents/manifesto.pdf

- 59. Citizens Wire. Pakistan people’s party parliamentarians manifesto. 2013. http://www.citizenswire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/PPPP_Manifesto_14_3_13.pdf

- 60. Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf Manifesto. PTI maifesto election 2013. http://www.insaf.pk/about-us/know-pti/manifesto.

- 61. Muttahida Qaumi Movement manifesto. Empowering people MQM manifesto 2013. http://www.mqm.org/Assets/MQM-Manifesto-2013-Eng.pdf

- 62. Social Science and Policy Bulletin. Department of economics, lahore university of management sciences. 2009. https://lums.edu.pk/sites/default/files/research-publication/sspb-vol-1-no1-summer2009.pdf

- 63. Das D, Mohamed H, Saeed MT, et al. . World Bank/UNICEF. Strategic Choices for Education Reforms. Early Childhood Development in Five South Asian Countries. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATIONLP/Resources/460908-1209498676534/4950769-1217974426107/SouthAsiaECDPaper1.pdf

- 64. Haddad L, Acosta AM, Fanzo J. Accelerating reductions in undernutrition: what can nutrition governance tell us. Institute of Development Studies: University of Sussex Brighton, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pomeroy-Stevens A, D’Agostino A, Adero N, et al. . Prioritizing and funding the Uganda nutrition action plan. Food Nutr Bull 2016;37(4 suppl):S124–S141. 10.1177/0379572116674554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Colombia. Early childhood development. SABER country report 2013. http://wbgfiles.worldbank.org/documents/hdn/ed/saber/supporting_doc/CountryReports/ECD/SABER_ECD_Colombia_CR_Final_2013.pdf

- 67. Acosta AM. Analysing success in the fight against malnutrition in Peru. IDS Working Papers 2011;2011:2–49. 10.1111/j.2040-0209.2011.00367.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]