Abstract

For the primary health worker in a low/middle-income country (LMIC) setting, delivering quality primary care is challenging. This is often complicated by clinical guidance that is out of date, inconsistent and informed by evidence from high-income countries that ignores LMIC resource constraints and burden of disease. The Knowledge Translation Unit (KTU) of the University of Cape Town Lung Institute has developed, implemented and evaluated a health systems intervention in South Africa, and localised it to Botswana, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Brazil, that simplifies and standardises the care delivered by primary health workers while strengthening the system in which they work. At the core of this intervention, called Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK), is a clinical decision support tool, the PACK guide. This paper describes the development of the guide over an 18-year period and explains the design features that have addressed what the patient, the clinician and the health system need from clinical guidance, and have made it, in the words of a South African primary care nurse, ‘A tool for every day for every patient’. It describes the lessons learnt during the development process that the KTU now applies to further development, maintenance and in-country localisation of the guide: develop clinical decision support in context first, involve local stakeholders in all stages, leverage others’ evidence databases to remain up to date and ensure content development, updating and localisation articulate with implementation.

Keywords: public health, health systems, treatment

Summary box.

Clinical guidance frameworks and evidence synthesis products are largely designed for and draw on evidence from high-income countries (HIC) and do not usually speak to the low/middle-income country (LMIC) need for comprehensive, up-to-date decision support.

The Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide is a comprehensive, evidence-informed approach to clinical care that supports primary care improvement initiatives in South Africa and has been localised for several large LMICs.

We triangulated HIC evidence synthesis product recommendations and WHO guidance with LMIC clinical practice and resource constraints to ensure guidance that is both relevant to local realities and easy to update.

Development, maintenance and in-country localisation of PACK offer ongoing opportunity for interrogation and augmentation of health system issues.

These processes should involve relevant stakeholders to ensure recommendations are locally relevant and can streamline delivery of primary care.

Delivering quality primary care is difficult

For the primary care health worker in a low/middle-income country (LMIC), delivering effective care is complex and challenging: health facilities are inadequately staffed, the staff who are there are often inadequately trained or supported to act as independent clinicians, resources and medication availability are limited, and the patient load is large and increasingly complex with comorbidities and conditions requiring chronic care.1 2

Health workers are usually taught in hospitals and learn to approach the patient as a collection of systems (abdominal, thoracic, neurological, and so on). Outside the hospital, healthcare delivery is administered in silos determined largely by priority diseases and funding mechanisms, leading to vertical disease programmes implemented alongside one another within a primary care facility.

Yet it is a more complex and multimorbid reality which the primary care clinician faces – she or he is required in a consultation to address the concerns of a person (who may have various health risks, multiple symptoms and several chronic conditions) using a perspective that has its foundation in a system-based education and in a context that perpetuates fragmentation of care into vertical programmes.3

The health worker is overwhelmed by guidance

A predominant strategy for supporting health workers in primary care is the provision of clinical guidance, usually in the form of clinical practice guidelines, policy-based protocols and essential medicine lists. Health workers are expected to comply with a plethora of these, even though they may be out of date or inconsistent with one another.4

The guideline development community is attempting to make the provision of clinical guidance standardised, more robust and relevant. Various frameworks and standards for clinical practice guideline development,5 6 adaptation7 and implementation8 exist to support guideline developers, policymakers and clinicians craft guidance that is both usable and evidence informed, and calls are increasing for greater clarity and brevity of recommendations, with improved formatting of content, in particular greater use of algorithms.9 10 Evidence synthesis products like UpToDate and British Medical Journal (BMJ) Best Practice go some way to providing accessible, instant, evidence-informed answers for clinical queries, but are still largely arranged by disease or system, and target high-income country settings. This is because most guideline frameworks and development work, as well as sources of published evidence, originate in high-income countries and inadequately address the far more limited resources and skills and burden-of-disease patterns in LMICs.

The WHO has produced policy frameworks and clinical guidelines for LMIC settings, some of which, like the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness strategy11 for under-five care, and Mental Health Gap Action Programme12 for mental health and neurological disorders, have been disseminated widely. However, many WHO guidelines still have a disease or system focus, limiting their usefulness in a comprehensive primary healthcare setting and prompting increasing demand for integrated decision support tools for primary care.13

Getting practical: the Practical Approach to Care Kit

Since 1999, the Knowledge Translation Unit (KTU) has developed a health systems intervention that attempts to streamline the care delivered by frontline clinicians. Now called the Practical Approach to Care Kit, PACK is a programme comprising clinical guidance, an implementation strategy, health systems strengthening and monitoring and evaluation components. PACK has its roots in the WHO strategy, Practical Approach to Lung Health and adopts its symptom-based approach.14 Initially focused on lung health and tuberculosis primary care in South Africa (Practical Approach to Lung Health in South Africa—PALSA),15 it has incrementally expanded to include HIV and sexually transmitted infections (Practical Approach to Lung Health and HIV/AIDS in South Africa—PALSA PLUS), and then comprehensive adult care (initially Primary Care 101) through many cycles of development, refinement, evaluation and testing.16 It has been introduced throughout primary care facilities in South Africa in support of national department of health policy initiatives like Nurse-Initiated Management of Antiretroviral Treatment and currently forms a central clinical component of the government’s Ideal Clinic Initiative.17 Working with local health providers, academics and clinicians, we have supported the localisation of the PACK programme to Botswana,18 Brazil,19 Nigeria, Ethiopia and, currently, China.

Four pragmatic randomised controlled trials evaluating PACK and its predecessor programmes in South Africa involving 33 000 patients from 124 clinics across seven health districts showed significant and reproducible improvements in quality of care, health outcomes and healthcare utilisation, predominantly for communicable diseases.20 21 22 23 Parallel qualitative evaluations record clear benefit to health worker morale, with primary care health workers consistently reporting a sense of empowerment as independent clinicians.24 25

A core component of this intervention is a clinical decision support tool, the PACK guide. Unusual among clinical practice guidelines, the PACK guide is commonly used by clinicians during a primary care consultation.26 27 To date, we have produced over 20 editions and printed 300 000 copies in South Africa alone. And despite renaming and rebranding over the years, PACK has survived as a go-to resource for primary care health workers throughout South Africa who describe it as ‘A tool for every day for every patient’.28

The PACK Adult guide29 is a 120-page clinical decision support tool that aims to be the only resource a clinician needs to consult during a primary care consultation. The first 70 pages cover an approach to common symptoms and the second section an approach to chronic conditions including infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, mental health, reproductive health, musculoskeletal conditions and palliative care. It also includes pages on general health screening, rational prescribing, and preventing and managing the infectious and psychological risks of being a health worker.

Developing practical clinical decision support

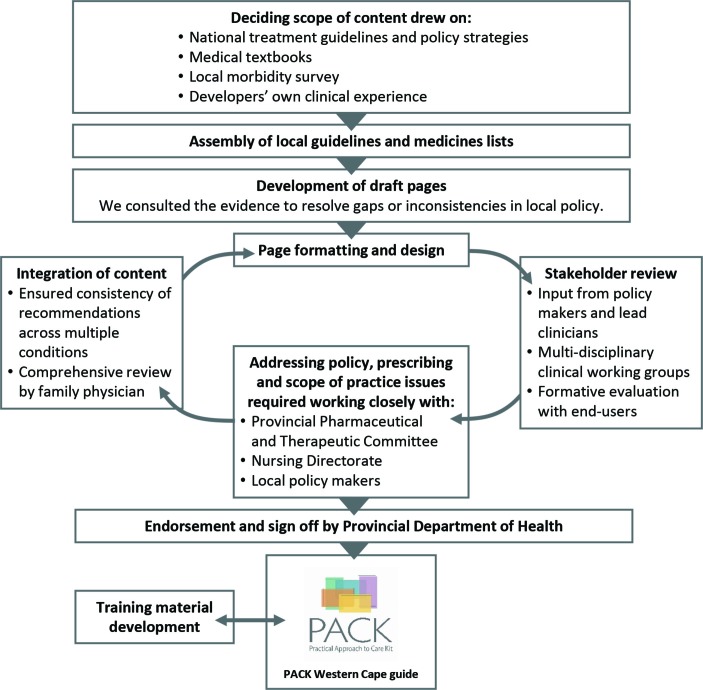

In 2006, following requests from end-users and policymakers, we began a 4-year process of expanding the respiratory and HIV-focused content of PALSA PLUS to create a comprehensive approach to adult care. Figure 1 depicts the development process of the PACK guide in the Western Cape province of South Africa. We drew on existing national standard treatment guidelines,30 medical textbooks (especially Harrison’s approach to common symptoms)31 and national strategic plans32 and aligned the content to local provincial policy, burden of disease33 and resource realities.

Figure 1.

Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide development process

We now update the PACK guide annually to keep pace with rapidly evolving evidence and policy, particularly for ‘high churn’ areas like HIV and tuberculosis. The initial expansion of PALSA PLUS to PACK drew on 171 contributors in the Western Cape from a range of disciplines—clinicians (primary care and disease specialist), policymakers, pharmacists, counsellors, patient advocates and others involved in delivering and supporting primary care—either in 1 of 10 clinical working groups or as individual reviewers. Subsequent annual revisions have involved the recruitment of more stakeholders, and created an active forum for debating evidence and for identifying errors, lack of convergence with other guidelines and priorities for new content.

Training material development carefully articulates with the guide’s clinical content and guide developers also participate in implementation planning and delivery.

To extend the value of PACK to other countries, we have developed a globally relevant version of the guide to serve as a template for LMIC in-country localisation by triangulating each of the 2372 recommendations in PACK Western Cape with international evidence sourced through BMJ Best Practice, WHO guidance and other sentinel guidelines (figure 2). To support in-country localisation of this PACK Global guide, training materials and implementation approach to local priorities, scope of practice and resources, we designed a localisation toolkit and KTU mentorship package. The PACK programme localisations and lessons learnt from this process are described elsewhere in this Collection.34

Figure 2.

Leveraging evidence synthesis in high-income countries to build an evidence base for LMIC primary care.41 42 HIC, high-income country; KTU, Knowledge Translation Unit; LMIC, low/middle-income country; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit.

Addressing what the patient, the clinician and the health system need from clinical guidance

Throughout the development, maintenance and localisation of the PACK guide, we have strived to make it easier for clinicians to deliver primary care by addressing the needs of the patient, the clinician and the health system.

Addressing what the patient needs from clinical guidance

Patients’ needs are complex and with increasing age and life expectancy, comorbidities and chronicity are more common than not. These needs demand a comprehensive and integrated approach. PACK Adult is a comprehensive guide to adult primary care, covering over 500 symptoms, syndromes, risks and conditions. Being comprehensive allows it to prompt the screening for and management of common priority conditions. The content has been carefully integrated so that recommendations are consistent throughout (eg, the same cholesterol threshold prompts treatment and referral across cardiovascular disease and HIV) and the care of the patient with multiple problems is prompted and facilitated. Integrating the routine care of common comorbidities makes more efficient the delivery of care to the patient with more than one chronic condition into a single consultation.

Addressing what the clinician needs from clinical guidance

In a busy primary care facility, a clinician needs a decision support tool that is appealing and easy to use during a clinical consultation, which supports the flow of clinical decision-making and does not distract from the interaction with the patient. To achieve this, we have employed a specific language style, clinical approach, graphic design and hard copy elements, the features of which and rationale for use are listed in table 1. These design features enable the PACK guide to accommodate more clinical detail than many standard, telephone directory length clinical practice guidelines, and allow for their use during each consultation. The PACK guide is currently printed in hard copy but is also available as an interactive pdf for use on a tablet, desktop computer or laptop.

Table 1.

PACK guide features

| Feature | Rationale for feature | Example |

| Clinical approach | ||

| Symptom based | Patients usually present with symptoms, not diagnoses, so this takes the patient’s presentation as the starting point. Unlike a guideline with a disease entry point, it can prompt screening for and diagnosis of chronic conditions. | Each symptom is arranged on its own page. The ‘Collapse’ page prompts consideration of eight ‘chronic conditions’ which may still be undiagnosed or uncontrolled. These include ischaemic heart disease, diabetes, stroke, a mental health condition, epilepsy and pregnancy. |

| Syndromic approach to assessment and management | Ensures that the user with limited clinical skill and experience will still be prompted to manage the patient safely, even in the absence of a certain diagnosis, while recognising limited capacity of most LMIC primary care facilities to confirm a diagnosis with available tests and investigations. | The syndromic approach may lead to a ‘likely’ diagnosis and appropriate management plan. For patients needing urgent care, it may not define a diagnosis but rather urgent empirical management for potentially life-threatening conditions (eg, meningitis) and immediate referral. |

| History taking, examination and investigations incorporated into clinical approach | Avoiding vague prompts like ‘Take a history’ or ‘Do a thorough examination,’ PACK elicits those details relevant to the particular symptom or condition and provides a clear response to each. | Headache page algorithm: ‘Is headache disabling and recurrent with nausea or light/noise sensitivity, that resolves completely? If Yes: Migraine likely.’ |

| Content focuses on what actions the clinician should take | PACK avoids explanations of pathophysiology, public health prioritisation or pharmacodynamics as it aims to support the busy clinician in a consultation and needs to be as brief as possible. | The ‘Hypertension: diagnosis’ page does not provide details of the prevalence or pathophysiology of hypertension, but instead gives clear instructions on how to take a blood pressure correctly, how to interpret the result and when to repeat it if raised. |

| Language style | ||

| Concise | Enables regular reference in busy primary care consultations and allows a comprehensive approach in a 120-page guide. | |

| Plain language, avoids medical jargon | Empowers use in clinician with limited skill or experience. Makes health knowledge more accessible. | ‘Difficulty breathing’ instead of ‘dyspnoea’ |

| Addresses user in the active voice | Clearly places responsibility for action with the clinician. | ‘Test cholesterol’ instead of ‘Cholesterol tests should be done in all patients.’ |

| Focuses on the individual patient | It ensures a focus on the individual patient by dealing with only the patient in the current consultation, not all patients. | On the Stroke page: ‘Help the patient to manage his/her CVD risk’ instead of ‘Advise all patients with stroke to manage their cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.’ |

| Standard phrasing | Standard phrasing for common management, screening and referral recommendations increases their familiarity across the guide. |

|

| Formatting and design | ||

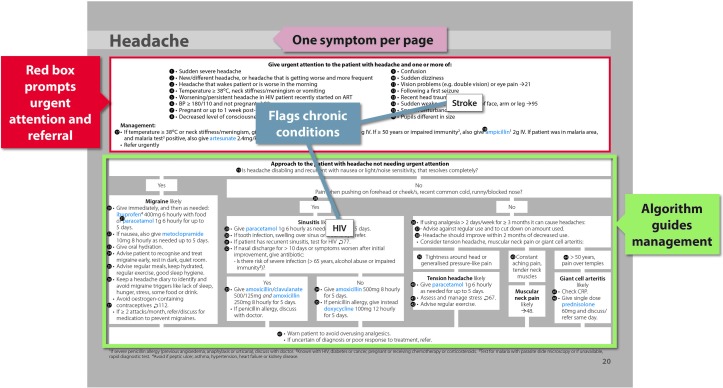

| Clinical approach to symptoms arranged in algorithms | Makes the clinical decision-making process explicit and prompts decision-making in a stepwise fashion. Unlike recommendations presented in narrative format, all possible responses to key questions and findings are presented. | See figure 3. |

| Algorithms flow from top to bottom | Readers approach text from the top and work down; it also provides equal weighting to decision-making in an algorithm. This is different from WHO guidance, typically arranged from left to right. | See figure 3. |

| Standard format of pages | This builds familiarity with the approach and can help establish a pattern to a clinical consultation, especially useful when a patient has several symptoms or conditions. |

|

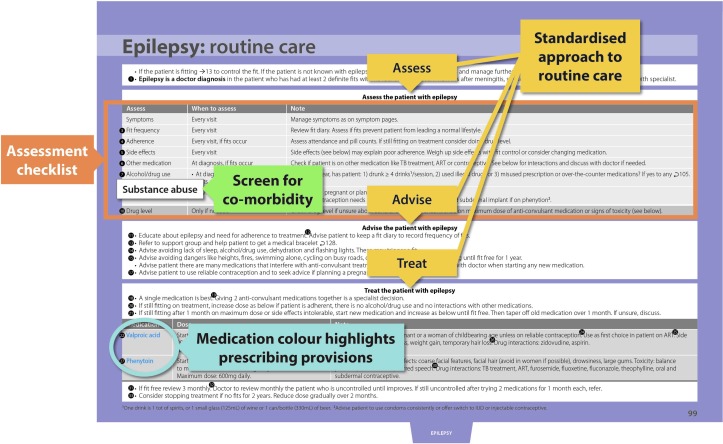

| Checklists | Provides a very simple, yet systematic approach to routine care for the patient with a chronic condition adopting a health systems approach which defines ‘chronic’ as anything that requires repeated, planned visits to care. | Checklists can form the main structure of pages for chronic conditions using the ‘Assess, Advise, Treat’ framework (figure 4) but can also be embedded in boxes of content like warning signs for a headache that may warrant immediate referral. |

| Colour coding indicates scope of practice, urgency and content sections | Colour breaks the monotony of a monochrome design. Colour coding aids efficient use and can enhance recommendations. |

|

| Illustrations and photographs | Useful to guide likely diagnosis, provide prompts for shared decision-making with a patient and to demonstrate a management option to a patient. |

|

| Arrows guide the user to relevant pages | Arrows prompt the user to consult several relevant pages, enabling integrated care within one consultation. |

|

| Hard copy features | ||

| Ring bound | Makes page turning and place holding easier. | |

| Printed on durable paper | Aids regular use for at least a year until the next update. | – |

| Sections demarcated with tabs | Facilitates finding the sections easily. | – |

| Content limited to 1–5 pages per symptom or condition | To limit the guide’s size and to maintain a focus on priority common conditions for LMIC primary care. | An approach to most symptoms is contained in one page; the chronic condition sections span 1–5 pages depending on the scope required for LMIC primary care—‘HIV routine care’ has 5 pages, dementia 1. |

LMIC, low/middle-income country; PACK, Practical Approach to Care Kit.

Figure 3.

Algorithm format of Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) guide symptom pages.

Figure 4.

Standardised format of routine chronic condition care pages.

Addressing what the health system needs from clinical guidance

A primary healthcare system needs clinical guidance that supports ‘complete technical integration’35 of health services and clinical care. PACK aims to be implementable in the setting for which it is intended—all its recommendations must be feasible given local policy, resource availability and clinician scope of practice. Thus, the processes of developing, revising and later localising the PACK guide have entailed the interrogation and augmentation of various features of the health system.

Attempting to align clinical recommendations with local policy has highlighted gaps in and discrepancies between policies that have led to adjustments in the policies themselves. Interrogation of these policies with end-users has also highlighted the gaps between the policies and on-the-ground practice, skills and resource availability, and has provided the opportunity to align policy with reality.

By delineating the scope of care for each cadre of health worker and clarifying referral pathways, PACK can facilitate task-sharing and streamline care. During localisation, medication, investigations and referrals in the PACK guide can be colour coded according to level of health worker permitted to perform each activity. Clarifying roles in this way helps to ensure that clinicians both fulfil their responsibilities completely and avoid working beyond their scope, but has also at times prompted the expansion of clinician scope, particularly prescribing provisions to expand access to chronic condition medication for high burden conditions. This is proving highly valued by front-line clinicians who often feel compelled to operate outside what they understand to be their scope of practice (particularly in emergency situations) and shifts the responsibility for scope of practice decisions from urgent, stressful moments in clinical practice to central policymakers.

The evidence-informed updates to the PACK Global guide are incorporated into annual updates of the South African policy-aligned guide and other country PACK versions. This is tailored to what local policy and resources allow, but can in turn prompt official review and update of local policies too.

What have we learnt?

Designing comprehensive, integrated clinical guidance that is usable in a complex health system is not without challenges, and these have provided many lessons that we continue to apply to our content development work.

Develop clinical decision support in context first

Designing algorithms that reflect clinical decision-making processes is a complex activity and attempting to do so based solely on grade-type evidence and sentinel guidelines was extremely difficult. This taught us the value of developing clinical decision support within a specific context and the importance of testing out real-world clinical scenarios on evolving algorithms and checklists. For example, the South African Hypertension Guidelines36 define malignant hypertension and include seizures as a diagnostic sign. The practical implications of this definition were challenged by an epilepsy clinical working group considering primary care referral criteria. Blood pressure is commonly elevated after a seizure. Thus, it is inappropriate to consider all such patients as having malignant hypertension. This criterion was refined with input from a primary care clinician, nephrologist and neurologist. This illustrates the process of triangulating evidence with policy and the practical wisdom (phronesis) that underpins the delivery of clinical care.

Involve local stakeholders in all stages

A critical element to PACK’s success has been the level of local stakeholder involvement in all stages of its development, updating and localisation. This has provided a non-judgemental place in which to allow discourse between planners and providers and has meant that issues raised by draft guide pages highlighting conflicts of policy, ‘best practice’ and what was practical on the ground could be teased out, giving rise to acceptable and feasible recommendations. This and PACK’s responsiveness to end-user need has generated increasing levels of ownership of the programme, in turn strengthening the links between the various cadres of staff and levels of care, easing task sharing and clarifying scope of practice (particularly prescribing powers) and referral pathways. Although mediating the occasional dispute between policymakers and clinical opinion leaders can be challenging, that the Western Cape PACK guide annual review incorporates extensive end-user feedback has been essential to achieving buy-in into the programme and its decade-long endurance in the system. PACK is truly an example of a ‘living guide’.37 For example, when PACK trainers in the Western Cape found nurses struggling to interpret peak expiratory flow graphs in the chronic respiratory disease section of the PACK guide, this prompted the inclusion in a recent guide update of an eight-step set of instructions for reading, interpreting and acting on results of peak expiratory flow.

Balance clinical priorities with brevity

The volume and density of PACK guide content, while reflecting end-user need, can compromise usability. We have in part addressed this issue by using key messages and a training approach that focuses on clinical priorities. We also pay constant attention to the brevity of recommendations and carefully interrogate the choice of each condition for inclusion in the guide: the need to strike a balance between public health and clinical priorities and the space on the page forces us to omit guidance for less common conditions (like systemic lupus erythematosus) or less frequently occurring comorbidities (eg, diabetes control in the person with arthritis).

Leverage others’ evidence databases to remain up to date

Once we recognised the need to build an evidence base for PACK, we commenced the evidencing process with a scoping exercise in collaboration with the local Cochrane Centre, but this revealed that conducting primary evidence searches on every one of PACK’s 2372 recommendations would be so time consuming that the guide would never be completed, let alone updated. Linking the production of each of the PACK guide recommendations to BMJ Best Practice evidence synthesis processes has allowed for a systematic and reliable evidencing and updating process and, as suggested by Elwyn et al, provides a ‘possible route to scale’.38

Conclusion

The PACK guide is the only annually updated, comprehensive, evidence-informed clinical decision support tool designed for LMIC primary care settings. Research evidence shows that the PACK intervention can support a clinician to deliver primary care more effectively. As it is a complex intervention, it is difficult to quantify the contribution of each component to this improvement; however, our qualitative evaluation work showed that the enabling format of the guide, with an expanded role particularly for nurses, was a critical enabler for the intervention’s success.24 25 It has been developed in a context where evidence and policy change repeatedly and frequently which has prompted a shift from the ‘all-knowing’ to the ‘all-learning’ health system and thus a greater need for and dependency on clinical decision support tools.

A revised version of the PACK Adult Global guide is now being published annually, addressing an important gap for countries where clinical guidance is usually updated at best five to seven yearly. We are also expanding the content set to cover the life course and support each cadre of health worker in primary care, with PACK Child (0–9 years)39 40 and PACK Adolescent (10–19 years) in pilot and development phases. PACK Community, a set of tools for community health workers that includes screening tools, a decision support guide, patient information leaflets and a guide to communication skills, is also in early development stage.

Thus, the PACK suite, once fully developed, will be comprehensive and integrated across disease silos, age groups and primary levels of care, and in its implementation, will serve as a health system intervention catalyst, making it easier for the clinician to deliver effective primary care.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: Led by RC, SP, CW, AA, EC and JH are the KTU content team that developed and maintain the PACK guide and related tools. LF, with support from EB and MZ, conceptualised the PACK approach. TD provided editorial support to this paper. RC wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed intellectual content, edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding: The initial expansion of PALSA PLUS to Primary Care 101 and then PACK was funded by the University of Cape Town Lung Institute, the South African National Department of Health and the Chronic Disease Initiative in Africa (CDIA) through an award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for Global Health Activities in Developing Countries to Combat Non-Communicable Chronic Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Diseases. The KTU received funding for the development of the evidence database for the PACK guide and linkage to the BMJ’s Best Practice and WHO guidance from the Peter Sowerby Charitable Foundation. The Stellenbosch University Rural Medical Education Partnership Initiative (SURMEPI) funded a writing retreat that supported the development of this paper. TD’s time was supported by the South African Medical Research Council. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Competing interests: JLH is an ex-employee of the KTU. TD is an employee of the South African Medical Research Council. MZ is an employee of the Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. EB reports personal fees from ICON, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Cipla, Menarini, ALK, Sanofi Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca, and grants for clinical trials from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann le Roche, Actelion, Chiesi, Sanofi-Aventis, Cephalon, TEVA and AstraZeneca. All of EB’s fees and clinical trials are for work outside the submitted work. EB is also a member of Global Initiative for Asthma Board and Science Committee. Since August 2015 the KTU and BMJ have been engaged in a non-profit strategic partnership to provide continuous evidence updates for PACK, expand PACK-related supported services to countries and organisations as requested, and where appropriate license PACK content. The KTU and BMJ cofund core positions, including a PACK Global Development Director, and receive no profits from the partnership. PACK receives no funding from the pharmaceutical industry. This paper forms part of a Collection on PACK sponsored by the BMJ to profile the contribution of PACK across several countries towards the realisation of comprehensive primary healthcare as envisaged in the Declaration of Alma Ata, during its 40th anniversary.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Oni T, Unwin N. Why the communicable/non-communicable disease dichotomy is problematic for public health control strategies: implications of multimorbidity for health systems in an era of health transition. Int Health 2015;7:ihv040–9. 10.1093/inthealth/ihv040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Afshar S, Roderick PJ, Kowal P, et al. Multimorbidity and the inequalities of global ageing: a cross-sectional study of 28 countries using the World Health Surveys. BMC Public Health 2015;15:776 10.1186/s12889-015-2008-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O. False dichotomies in global health: the need for integrative thinking. Lancet 2017;389:667–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Machingaidze S, Grimmer K, Louw Q, et al. Next generation clinical guidance for primary care in South Africa - credible, consistent and pragmatic. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195025 10.1371/journal.pone.0195025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The AGREE Next Steps Consortium. 2009. Appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument. https://www.agreetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/AGREE_II_Users_Manual_and_23-item_Instrument_ENGLISH.pdf

- 6. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:380–2. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. The ADAPTE collaboration. 2009. The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation. Version 2.0. https://www.g-i-n.net/document-store/working-groups-documents/adaptation/adapte-resource-toolkit-guideline-adaptation-2-0.pdf

- 8. Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michie S, Johnston M. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ 2004;328:343–5. 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Palda VA, et al. How can we improve guideline use? A conceptual framework of implementability. Implement Sci 2011;6:26 10.1186/1748-5908-6-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organisation. 2018. Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/child/imci/en/ (accessed Apr 2018).

- 12. World Health Organisation. 2016. mhGAP Intervention Guide - Version 2.0 for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/mhGAP_intervention_guide_02/en/ [PubMed]

- 13. Vasan A, Ellner A, Lawn SD, et al. Strengthening of primary-care delivery in the developing world: IMAI and the need for integrated models of care. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e321–3. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70102-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organisation. Practical approach to lung health – manual on initiating PAL implementation, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. English RG, Bateman ED, Zwarenstein MF, et al. Development of a South African integrated syndromic respiratory disease guideline for primary care. Prim Care Respir J 2008;17:156–63. 10.3132/pcrj.2008.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fairall L, Bateman E, Cornick R, et al. Innovating to improve primary care in less developed countries: towards a global model. BMJ Innov 2015;1:196–203. 10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. South Africa National Department of Health Ideal Clinic. 2017. What is an Ideal Clinic?https://www.idealclinic.org.za/

- 18. Tsima BM, Setlhare V, Nkomazana O. Developing the Botswana Primary Care Guideline: an integrated, symptom-based primary care guideline for the adult patient in a resource-limited setting. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:347–54. 10.2147/JMDH.S112466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wattrus C, Zepeda J, Cornick R, et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Brazil. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, et al. Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;331:750–4. 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zwarenstein M, Fairall LR, Lombard C, et al. Outreach education for integration of HIV/AIDS care, antiretroviral treatment, and tuberculosis care in primary care clinics in South Africa: PALSA PLUS pragmatic cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2011;342:d2022 10.1136/bmj.d2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fairall L, Bachmann MO, Lombard C, et al. Task shifting of antiretroviral treatment from doctors to primary-care nurses in South Africa (STRETCH): a pragmatic, parallel, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;380:889–98. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fairall LR, Folb N, Timmerman V, et al. Educational outreach with an integrated clinical tool for nurse-led non-communicable chronic disease management in primary care in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002178 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stein J, Lewin S, Fairall L, et al. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: a qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:240 10.1186/1472-6963-8-240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Georgeu D, Colvin CJ, Lewin S, et al. Implementing nurse-initiated and managed antiretroviral treatment (NIMART) in South Africa: a qualitative process evaluation of the STRETCH trial. Implement Sci 2012;7:66 10.1186/1748-5908-7-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCann N. An Evaluation of the current effectiveness of the PACK Programme February – July 2015 : Western Cape Department of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ana J, Sword C. Final Report on PACK Nigeria Adult Pilot Version 1.2, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. PACK film. 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lU894_NjE30&t=2s

- 29. PACK website. Available from: http://pack.bmj.com/

- 30. National Department of Health. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines List for South Africa Primary Health Care Level, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fauci A, Braunwald E. Harrison’s Principles of internal medicine. 14th edn: McGraw-Hill, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Health Systems Trust. South African National Department of Health’s 2004 policy document, Strategic Priorities for the National Health System, 2004-2009, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mash B, Fairall L, Adejayan O, et al. A morbidity survey of South African primary care. PLoS One 2012;7:e32358 10.1371/journal.pone.0032358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cornick R, Eastman T, Wattrus C. Crossing borders: the PACK experience of disseminating a complex health system intervention across low and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001088. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horton R. Offline: The tasks facing Dr Tedros. Lancet 2017;390:2538 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33137-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seedat YK, Rayner BL, Veriava Y. Hypertension guideline working group . South African hypertension practice guideline 2014. Cardiovasc J Afr 2014;25:288–94. 10.5830/CVJA-2014-062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. American College of Chest Physicians 2018. Four Questions With Dr. Richard Irwin on CHEST Living Guidelines. http://www.chestnet.org/News/Blogs/CHEST-Thought-Leaders/2016/01/Dr-Richard-Irwin-on-CHEST-Living-Guidelines (accessed 26 Apr 2018).

- 38. Elwyn G, Wieringa S, Greenhalgh T. Clinical encounters in the post-guidelines era. BMJ 2016;353:i3200 10.1136/bmj.i3200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Picken S, Hannington J, Richards M, et al. PACK Child: a practical guide to expand integrated paediatric primary care. BMJ Global Health 2018. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murdoch J, Curran R, Bachmann M, et al. Strengthening the quality of paediatric primary care in South Africa: protocol for process evaluation of a pilot and feasibility study of a health systems intervention. BMJ Global Health 2018. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Somannavar S, Ganesan A, Deepa M, et al. Random capillary blood glucose cut points for diabetes and pre-diabetes derived from community-based opportunistic screening in India. Diabetes Care 2009;32:641–3. 10.2337/dc08-0403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organisation , 2018. Institutional repository forinformation sharing. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/ (accessed Apr 2018).