Summary:

Innate and adaptive lymphocytes employ diverse effector programs that provide optimal immunity to pathogens and orchestrate tissue homeostasis, or conversely can become dysregulated to drive progression of chronic inflammatory diseases. Emerging evidence suggests that CD4+ T helper cell subsets and their innate counterparts, the innate lymphoid cell (ILC) family, accomplish these complex biological roles by selectively programming their cellular metabolism in order to instruct distinct modules of lymphocyte differentiation, proliferation, and cytokine production. Further, these metabolic pathways are significantly influenced by tissue microenvironments and disease states. Here we summarize our current knowledge on how cell-intrinsic metabolic factors modulate the context-dependent bioenergetic pathways that govern innate and adaptive lymphocytes. Further, we propose that a greater understanding of these pathways may lead to the identification of unique features in each population and provoke the development of novel therapeutic strategies to modulate lymphocytes in health and disease.

Introduction

At the time of intial priming, CD4+ T cells differentiate into various effector subsets, guided by specific antigen presenting cells and the cytokine mileu. Recent studies have defined that differentiation and subsequent effector functions are accompanied by a switch in the metabolic programming which occurs in a context-specific manner to meet the bioenergetic demands created during infection or inflammation 1. Deciphering the relative importance of distinct metabolic pathways employed by cells is essential for greater understanding of immune cell biology in order to design future therapeutics. However, delineating the metabolic dependencies of immune cells is complicated by the extensive interdependence between the primary bioenergetic pathways.

In brief, cells derive energy, stored as ATP and NADH, from the oxidation of glucose through glycolysis, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and the electron transport chain (ETC), to generate CO2 and water. Glucose is lysed to pyruvate that is converted to acetyl CoA at the inner mitochondrial membrane. Acetyl CoA is then shuttled into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle by conversion to citrate. Alternatively, under conditions of limiting oxygen, acetyl CoA is converted to lactate with the regeneration of NAD+. Cells undergoing rapid proliferation such as tumor cells and activated T cells utilize this pathway despite oxygen availability (referred to as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect), presumably to produce metabolites required for proliferation. Through the TCA cycle, acetyl CoA combines with oxaloacetate to form citrate and undergoes several conversions to reduce NAD+ to NADH for ATP generation via the ETC and yield metabolic intermediates for amino acid and fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acids (FA), like palmitate can serve as alternate source for acetyl CoA, through fatty acid oxidation (FAO), wherein FAs are catabolized to fatty acyl CoA and acetyl CoA. Furthermore, other catabolic pathways, such as glutaminolysis can feed into various stages of glycolysis and the TCA cycle thus providing an alternative fuel source. Also, metabolites from glycolysis are shuttled into the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) for the synthesis of nucleotides 1,2.

Intriguingly, T cells adapt their cellular metabolism to facilitate the bioenergetic needs of an appropriate immune response such as development or differentiation, cytokine production, and cell migration 2–4. This is best exemplified by the metabolic reprogramming that occur across subsets of CD4+ T helper (Th) cell populations in the context of infection or inflammation. Upon activation, naïve CD4+ T cell differentiate into distinct fates as a result of the cytokine microenvironment and this process is essential to provide optimal immunity or drive chronic inflammatory diseases. T helper (Th)1 CD4+ T cells, represented as a T-bet+ IFN-γ-producing subset, control intracellular infections as well as tumor growth, or drive type-1 chronic inflammatory responses. GATA3+ Th2 CD4+ T cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 to control helminth infections as well promote the wound healing process, or drive allergic inflammation. Th17 CD4+ T cells are RORγt+ IL-17 producers, found primarily in the intestinal mucosa and protect from pathogenic extracellular microbes, or drive chronic autoimmune inflammation. Finally, FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) can differentiate in the thymus or the periphery limit excessive immune responses and autoimmunity 5. Distinct cell-intrinsic metabolic checkpoints have been identified in each subset and are discussed more in depth below.

The innate lymphoid cell (ILC) family is defined by the lack classical lineage markers for CD4+ T cells, B cells, DCs, or macrophages, are enriched at barrier surfaces, and function primarily through the production of cytokines to modulate further immune responses, restore barrier integrity and maintain tissue homeostasis 6. ILCs can be considered an innate counterpart to the adaptive CD4+ T cell lineage, sharing similar transcriptional programs and cytokine effector profiles that allow them to be functionally classified into subsets analogous to helper CD4+ T cells. Group 1 ILCs (ILC1s) comprise NK cells and non-cytotoxic ILC1s that express T-bet and produce IFN-γ in response to infection 7. Group 2 ILCs (ILC2s) are GATA3+ cells capable of producing IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, and amphiregulin, serving critical roles in anti-parasitic immunity, allergic inflammation, and restoration of tissue integrity after damage 8. Group 3 ILCs (ILC3) express RORγt and produce IL-17 and IL-22 to combat intestinal infections, sustain intestinal barrier integrity, and maintain homeostasis with the commensal microbiota. ILC3 are further divided into T-bet+ ILC3s and CCR6+ lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi)-like ILC3s 6,9–11.

In contrast to CD4+ T cells, how ILC function or migration is influenced by specific metabolic pathways remains poorly defined. While ILC and CD4+ T cell subsets share expression of canonical lineage transcription factors, ILCs are not activated by a T cell receptor or co-stimulatory signaling (a crucial signal for T cell metabolic programming) and therefore may be more dependent on cell-extrinsic cues from the tissue environment such as cytokines or diet- and microbial-derived metabolites. This review summarizes the current literature on the cell-intrinsic and context-dependent metabolic programs that control the functional potential of effector CD4+ T cells as well as the growing interest in interrogation of ILC metabolism. Further, we also speculate on the biological importance of the conserved vs unique features between ILC and CD4+ T cell metabolism, drawing focus to the potential clinical implications of these findings.

Th1 CD4+ T cells, NK cells, and ILC1s

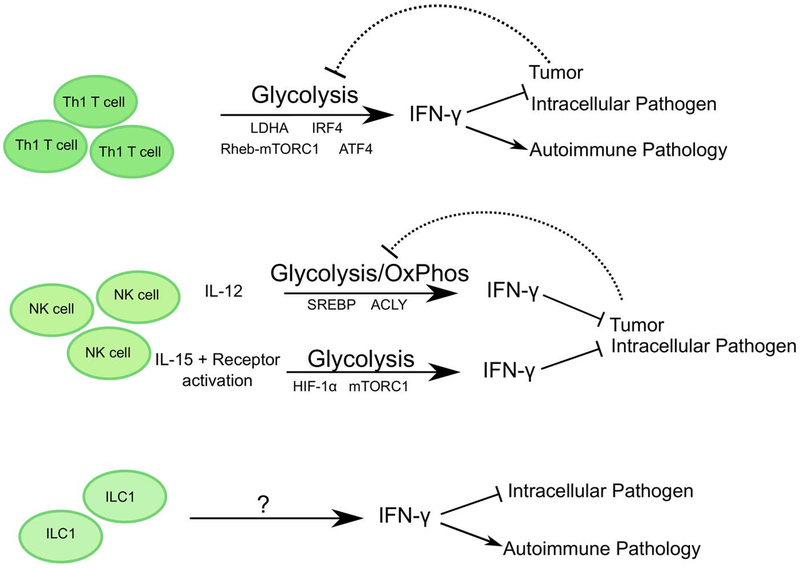

The activation and differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into effector cells is accompanied by a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. Despite inefficient ATP production, activated CD4+ T cells robustly employ aerobic glycolysis, as presented by the increased expression of glucose transporter, GLUT1 and glycolytic enzymes (such as hexokinase2), and the generation of large amounts of lactate (Warburg effect). Surprisingly, aerobic glycolysis is not necessary for proliferation or survival of the activated CD4+ T cells, but rather is important for effector cytokine production (Figure 1). Blockade of aerobic glycolysis results in substantially reduced IFN-γ production from CD4+ T cells generated in vitro or in vivo following infection with Listeria monocytogenes 12, and this mechanistically occurs by sequestering GAPDH to the glycolytic pathway, thus redirecting it from binding to the 3’ UTR of IFN-γ mRNA and permitting translation of IFN-γ 12. This may be of particular importance in the contexts when there is competition for nutrients, such as in tumors, where limiting glucose can impair aerobic glycolysis in Th1 CD4+ T cells and impair protective IFN-γ production 12.

Figure 1: Cell-intrinsic metabolic pathways employed by Th1 CD4+ T cells, NK cells and ILC1.

Th1 CD4+ T cells and NK cells employ distinct pathways to activate and support a predominantly glycolytic metabolic profile, to enhance IFN-γ mediated anti-viral and anti-tumor responses or autoimmune pathology. Activating stimuli, signaling molecules, transcriptional regulators, and specific tissue microenvironments critically influence these metabolic programs.

Consistent with this, the importance of aerobic glycolysis in Th1 CD4+ T cell function was also demonstrated by deletion of lactate dehydrogenase (LDHA) in CD4+ T cells, which causes activated cells to switch their metabolic profile back to oxidative phosphorylation and subsequently reduces IFN-γ production by impacting histone acetylation. The switch from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation shuttles acetyl CoA into the TCA pathway thus reducing availability for histone acetylation and activation of the IFN-γ locus 13. As a result, mice with a T cell-specific deletion of LDHA were protected from IFN-γ-induced autoimmune pathology 13. The reliance of Th1 CD4+ T cell function on glycolysis could also reduce the accumulation of harmful ROS produced via mitochondrial OxPhos 14. While low levels of ROS are required for CD4+ T cell activation, prolonged exposure to ROS causes cell death by altering components of DNA repair and signaling pathways 15. The glycolytic and OxPhos capacity of Th1 CD4+ T cells is also dependent on the transcription factor IRF4. In Th1 CD4+ T cells, IRF4 deletion caused the reduction of GLUT3 and hexokinase 2 expression and reduced expansion of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells, resulting in abrogated immunity to Listeria monocytogenes infection 16.

In a recent study, CD4+ T cell amino acid metabolism as well as glycolysis and OxPhos were shown to be dependent on ATF4, a transcription factor activated by oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress 17. ATF4 is activated in the presence of high levels of uncharged tRNAs and triggers the amino acid starvation response (AAR). ATF4 and the AAR then upregulate the expression of multiple enzymes involved in de novo amino acid synthesis as well as amino acid transporters, to increase intracellular amino acid availability for protein synthesis and cellular function. As such ATF4 deficiency can perturb multiple pathways including cellular ROS levels. ATF4-deficient CD4+ T cells, cultured in the absence of beta-mercaptoethanol, had reduced intracellular cysteine levels and subsequently lower levels of the antioxidant, glutathione. In the context of in vitro Th1 polarizing conditions, ATF4-deficient CD4+ T cells exhibited reduced proliferation and IFN-γ production, associated with lower expression of T-bet and higher FoxP3 17. In an in vivo mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), ATF4 deficiency reduced Th1 but increased Th17 CD4+ T cell differentiation and resulted in increased disease severity 17. The enhanced Th17 response was not a direct effect of ATF4 deletion in CD4+ T cells, rather due to increased IL-1β production by ATF4-deficient antigen presenting cells.

It is well established that mTOR activity is another inducer of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, PPP and lipid synthesis pathways 18. In support of this, Rheb mediated activation of mTORC1 is required for the in vitro differentiation of Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T cells, but not of Th2 in vitro. In an EAE mouse model, Rheb−/− CD4+ T cells induced reduced disease severity and instead differentiated into Th2 CD4+ T cells and induced a ‘non-classical EAE’ characterized by ataxia 19. Deletion of the mTORC1 adaptor protein, Raptor, also significantly blocked the differentiation of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells in vitro and in a Listeria infection model 20.

Similar to CD4+ T cells, resting NK cells (a member of the ILC family) utilize OxPhos (Figure 1). Intriguingly, in vitro receptor-activated IFN-γ production relies on glucose-dependent OxPhos while cytokine-induced IFN-γ production was independent of metabolism. Long-term priming with high dose IL-15 was capable of switching the requirement for OxPhos to glycolysis by receptor-activated NK cells 21,22. Furthermore, NK cells require mTORC1 activity to upregulate GLUT1 and glycolytic enzymes, for IFN-γ production and granzyme B expression, ex vivo and in vivo (with poly I:C injections) 23. This dependency on glucose for effector functions places NK cells at a disadvantage as sites of viral infection or tumors are typically deprived of glucose 24. To help compensate for this, IL-15 primed NK cells can also upregulate hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α) under hypoxic conditions, which increases their glycolytic potential and supports cell migration and cytotoxicity 25.

Interestingly, NK cell glycolysis and OxPhos is dependent on SREBP, a lipogenesis transcription factor. SREBP regulates the expression of ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) and citrate transporter Slc25a1 to shuttle citrate-malate across the mitochondrial membrane 26. NK cells depend on cytosolic citrate, which is cleaved to acetyl-CoA by ACLY, to sustain glycolysis. Inhibition of SREBP reduces glycolysis and OxPhos potential of NK cells, and notably diminishes cytotoxic activity against tumors. Interestingly, blocking fatty acid synthesis or fatty acid oxidation in NK cells had no impact on their function or metabolic profile 21,26, suggesting that NK cell function is more strictly dependent on glucose than lipids.

In addition to NK cells, a population of non-cytolytic ILC1 have been defined, that are potent sources of IFN-γ, but have a distinct developmental program dependent on T-bet rather than Eomes 7. As the most recently identified member of the ILC family, relatively little is known regarding the cell-intrinsic metabolic pathways employed by resting or activated non-cytolytic ILC1. Recent RNA-sequencing analyses of intestinal ILC1 populations from naïve mice revealed enrichment of transcripts associated with mTOR signaling 27, but the functional relevance of this pathway has not yet been explored. It is likely that similar to Th1 CD4+ T cells and NK cells, non-cytolytic ILC1 populations will employ complex and context-dependent bioenergetic pathways to support cell migration and function. These pathways may be modified by local availability of glucose or oxygen, and may hold an important key for determining the outcome of infection, inflammation or tumor progression.

Th2 CD4+ T cells and ILC2s

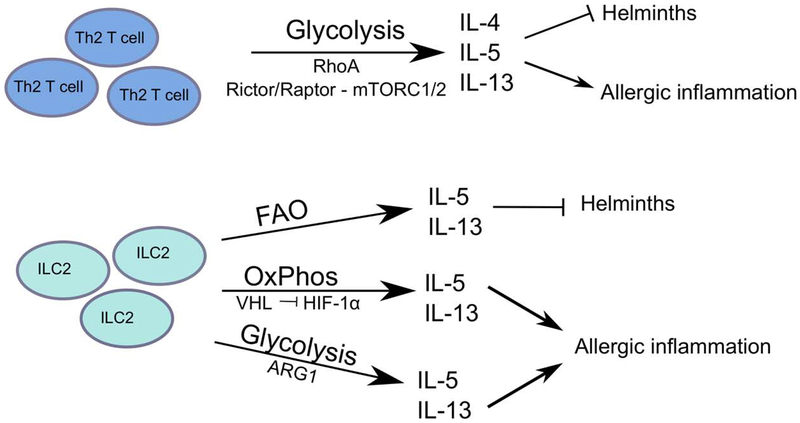

Th2 CD4+ T cells differentiate from naïve CD4+ T cells in the presence of cognate antigen and IL-4 and express GATA3 as their master transcription factor 28. Th2 CD4+ T cells are essential for the control of extracellular parasite or helminth infections but when unchecked contributes to the development of asthma, allergic inflammation and tissue fibrosis 28. Activated Th2 CD4+ T cells produce primarily IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13 to induce immunoglobulin class switch, recruit eosinophils and basophils, and induce mast cell degranulation 28. Activated Th2 CD4+ T cells are also dependent on glycolysis for differentiation and function (Figure 2), and RhoA, a GTPase signal transducer to cytoskeleton components, appears to be a critical regulator of the glycolytic potential of Th2 CD4+ T cells. Specifically, RhoA-deficient T cells exhibit a defect in Th2 differentiation and reduced allergic airway inflammation, and this was associated with lower levels of IL-4R, GATA3 and phosphorylated STAT6 levels 29. Conversely, hyperactivation of RhoA signals, by deletion of a negative regulator Rho GAP, exacerbated OVA-induced airway inflammation. Mechanistically, RhoA was found to critically support glycolysis, as blockade of glycolysis with the glucose analog 2-DG could recapitulate these phenotypes, and supplementing RhoA-deficient Th2 CD4+ T cell cultures with pyruvate was sufficient to restore IL-13 production 29. Further, this appears to be selective to Th2 CD4+ T cells, as RhoA−/− Th1 CD4+ T cells display no defect in glycolytic capacity and as such produced similar levels of IFN-γ as their wild type counterparts 29.

Figure 2: Cell-intrinsic metabolic pathways employed by Th2 CD4+ T cells and ILC2.

While Th2 CD4+ T cells predominantly utilize glycolysis to support effector function in the context of both helminth infections and adverse allergic responses, the metabolic profiles of ILC2s are influenced by tissue localization and activating stimuli. Accordingly, signaling pathways utilized by ILC2s vary by model and are distinct from pathways adopted by Th2 CD4+ T cells.

The mTORC1 pathway also regulates the glycolytic capacity of activated Th2 CD4+ T cells, but unlike Th1 CD4+ T cells, Rheb deletion did not reduce glycolysis in Th2 CD4+ T cells 19. Rather, mTORC1 inhibition by Raptor deletion significantly reduced glycolysis in Th2 CD4+ T cells and impaired Th2 differentiation as demonstrated by reduced expression of IL-4R, IL-2Ra, and GATA3 20. Similar to RhoA deletion, Raptor−/− Th2 CD4+ T cells exhibit an attenuated response in a model of allergic airway inflammation, characterized by reduced infiltration of eosinophils and reduced IL-4 and IgE 20. Direct inhibition of mTORC1 reduced the expression of genes associated with glycolysis, lipid biosynthesis and OxPhos 20. The mTORC2 pathway, which is impaired by deletion of Rictor, is also selectively associated with the impairment of Th2 CD4+ T cell differentiation, but not of Th1 or Th17 CD4+ T cells 19. Despite these advances, it is unclear how glycolysis and associated regulators mechanistically impact the expression of Th2 CD4+ T cell-associated cytokines, receptors and transcription factors.

ILC2s share a common transcriptional program and effector cytokine profile as Th2 CD4+ T cells, playing dual roles in either promoting host-protective responses of anti-parasitic immunity and tissue repair, or driving pathologic tissue inflammation 8,30. While much is known about the cell-extrinsic cytokine cues that drive ILC2 development, proliferation, and activation, the metabolic factors that regulate ILC2 biology are just beginning to be explored (Figure 2). Notably, activated ILC2s are capable of utilizing both aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in response to cytokine stimulation, as in vivo treatment with IL-33 resulted in higher rates of both glycolysis and OxPhos above those observed for Th2 CD4+ T cells 31. Despite this apparent metabolic plasticity, the functional in vivo relevance of these two pathways is likely dependent upon the inflammatory context and tissue environment in which the ILC2s are induced.

In the context of airway inflammation, recent studies have identified two metabolic pathways that affect ILC2 glycolytic function. Under conditions of hypoxia, one study found that deletion of VHL, a negative regulator of HIF-1α, impaired the maturation of lung ILC2s by affecting expression of IL-33R and thereby dampening cytokine production 32. Mechanistically, VHL deficiency increased HIF-1α levels, leading to an increase in glycolysis and a reciprocal decrease in OxPhos. Similar to T cells, the enhanced glycolysis in VHL-deficient ILC2s altered histone modifications at several major ILC2 genes 32. However, unlike CD4+ T cells where histone acetylation was reduced due to decrease in available acetyl-CoA, ILC2s had reduced histone methylation although the functional significance of distinction remains unclear 13,32.

In a different study under normoxic conditions, deletion of the amino acid catabolic enzyme Arginase 1 (Arg1) impaired ILC2 cytokine production and proliferation, thereby protecting against development of airway inflammation 31. Inhibition of Arg1 activity had broad effects on ILC2 metabolism, severely curtailing polyamine synthesis and reducing glycolysis. Whether this impairment in glycolytic capacity is due to insufficient metabolites for protein synthesis or other mechanisms is yet to be determined 31. Interestingly, Arg1 has also been identified in fetal ILC precursors 33, but whether this enzyme may instruct metabolic programming during early ILC development and lineage commitment is unknown.

In addition to glycolysis, recent evidence suggests that ILC2s can employ other metabolic pathways to fuel their effector functions. Research by Wilhelm et al found that among all ILC subsets, ILC2s exhibited the highest uptake of exogenous fatty acids from the environment, which was further increased in the absence of retinoic acid 34. While inhibition of FAO did not affect ILC2 development, limiting absorption of FA reduced cytokine production and impaired expulsion of Trichuris muris worms from the intestine 34. Intriguingly, blocking glycolysis did not impact anti-helminth immunity, suggesting a context-dependent distinction between the metabolic pathways engaged by ILC2s during intestinal immunity and those observed in studies of lung inflammation. Furthermore, the metabolic programming of ILC2s is likely to extend well beyond glucose metabolism, as RNA-sequencing analyses of naïve intestinal ILC2s revealed enrichment in transcripts associated with alanine/glutamate metabolism and sphingolipid metabolism 27. While the biological relevance of these pathways has yet to be explored in ILC2 biology, it suggests that ILC2 metabolic programming is multi-faceted. Taken together, these studies illustrate the complexity of ILC2 metabolism and suggest that ILC2 metabolic programming is highly adaptable depending upon the inflammatory stimulus and tissue environment.

Th17 CD4+ T cells and ILC3s

Th17 CD4+ T cells differentiate from naïve CD4+ T cells in the context of cognate antigen and stimulation with the cytokines IL-6, TGF-β and IL-23 35. Th17 CD4+ T cells express RORγt and produce IL-17 and to lower extent IL-22, to combat pathogenic bacteria and tumors, but are also major drivers of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, colitis and psoriasis 35. In contrast, in the presence of TGF-β and IL-2, but the absence of pro-inflammatory cytokines, naïve CD4+ T cells can differentiate into Tregs (induced or peripheral Tregs) 35. Tregs effectively curb the immune response by the secretion of IL-10, sequestration of IL-2 and expression of ligands to inhibitory receptors expressed on active immune cells 5,35.

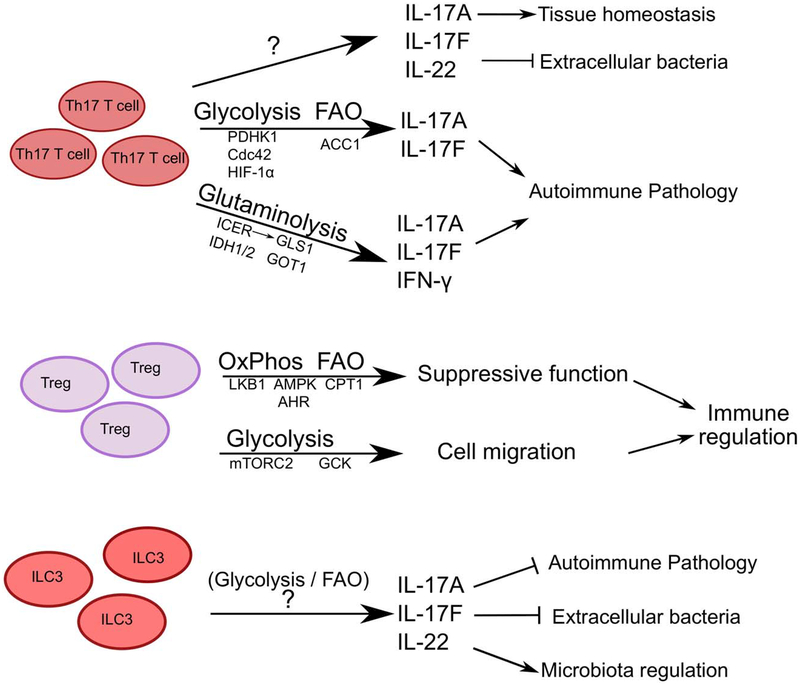

The metabolic dichotomy between effector and Tregs is well established as effector CD4+ T cells predominantly employ glycolysis and Tregs employ oxidative phosphorylation and FAO (Figure 3) 36. The proteomic analysis of human Tregs and conventional CD4+ T cells indicate that freshly isolated human Tregs utilize glycolysis while conventional T cells rely on FAO, which may be reflective of a resting state. Consistent with this, upon in vitro activation the metabolic profiles of human Tregs shifts to both glycolysis and FAO, while conventional T cells shift to predominantly glycolysis, and these shifted bioenergetic pathways were necessary for the proliferation and function of both subsets 37. Similar to human cells, a metabolite comparison of mouse in vitro differentiated Th17 CD4+ T cells and Tregs by liquid chromatography/gas chromatography-mass spectrometry demonstrated higher pyruvate and lactate levels in Th17 CD4+ T cells versus higher TCA intermediates and lower long chain fatty acids in Tregs, indicative of differential glycolysis, OxPhos and FAO 38. Further, blocking glycolysis impaired the differentiation of Th17 and Th1 CD4+ T cells, where as FoxP3+ Tregs were unaffected, yet could be reduced by blocking oxidative phosphorylation.

Figure 3: Cell-intrinsic metabolic pathways employed by Th17 CD4+ T cells, Tregs and ILC3.

Th17 CD4+ T cells and Tregs possess opposing metabolic profiles, dominated by glycolysis and glutaminolysis or OxPhos, respectively. As such these cell types employ distinct signaling moieties to maintain cellular metabolism for effector functions. While there are indications of glycolysis and FAO utilization, the metabolic pathways governing ILC3 function remain mostly unknown.

Various modifying or regulatory pathways can critically influence this generalized bioenergetic dichotomy of effector versus regulatory T cells. For example, increasing pyruvate oxidation by inhibiting or deleting PDHK1 (pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinase 1), an inhibitor of PDH, selectively shifts the differentiation of Th17 CD4+ T cells to a Treg phenotype by increasing the levels of ROS produced by OxPhos 38. Treatment with a PDHK1 inhibitor (DCA) ameliorated disease severity in an EAE mouse model, by reducing the number of infiltrating CD4+ T cells into the spinal cords and increasing the Treg population in the draining lymph nodes 38. Tregs exhibit resistance to ROS mediated stress, due to their high levels of antioxidant glutathione and thioredoxin 38. However, this is likely context dependent as Franchi et al identified that Th17 CD4+ T cells generated in vivo exhibit lower levels of glycolysis and PDHK1 than in vitro generated Th17 CD4+ T cells, and that in vivo Th17 CD4+ T cells rely primarily on OxPhos after activation for cytokine production 39. In support of these results, blocking OxPhos in an antigen-induced colitis or psoriasis mouse model reduced colonic inflammation or ear thickness, respectively. Furthermore, blocking OxPhos in PBMCs or lamina propria mononuclear cells (from inflamed tissue) from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) reduced the frequency of IL-17 producing T cells, in comparison to cells from healthy individuals 39. Cdc42, a Rho family GTPase, is another modifier of glycolysis in Th17 CD4+ T cells. Deletion of Cdc42 enhanced the differentiation of pathogenic Th17 CD4+ T cells as presented by increased RORγt, IL-17, IL-23R and IFN-γ, while reducing Treg development and stability, and was associated with an increased susceptibility to intestinal damage and inflammation 40. This shift towards pathogenic Th17 CD4+ T cells is regulated by the increase in glycolysis as culture with 2-DG reduced the levels of IL-17 from Cdc42-deficient CD4+ T cells to normal levels 40.

In addition to glucose, Th17 CD4+ T cells can also utilize glutamine via glutaminolysis as a source of energy. This process is regulated by the transcriptional factor ICER, which controls expression of glutaminase1 (GLS1), an enzyme that converts glutamine to glutamate and then subsequently to aspartate, pyruvate or α-ketoglutarate 41. In EAE mouse models, chemically blocking or shRNA mediated downregulation of GLS1 reduced Th17 CD4+ T cell responses, T cell infiltration into the spinal cord and overall disease severity. Critically, this modulation of occurred independent of changes to glycolysis, suggesting that dependency on glutaminolysis is advantageous to Th17 CD4+ T cell function in tissues with reduced glucose availability 41.

Following glutamine generation, the conversion to aspartate is catalyzed by glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 1 (GOT1), and this was found to occur in both Th17 CD4+ T cells and Tregs. Specifically, Xu et al identified aminooxy acetic acid (AOA) as a GOT1 inhibitor, which shifted the in vitro differentiation of Th17 CD4+ T cells to Tregs and substantially decreased the levels of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG, derivative of α-ketoglutarate) 42. Furthermore, IDH1 and IDH2, enzymes that convert α-ketoglutarate to 2-HG are upregulated in Th17 CD4+ T cells versus Tregs. Supplementing in vitro CD4+ T cell cultures with 2-HG was associated with increased expression of Th17 CD4+ T cell effector cytokines, and reduced FoxP3 expression due to by hypermethylation of the Foxp3 locus. Similar to blocking GLS1 in EAE models, AOA treatment reduced Th17 CD4+ T cell infiltration into the spinal cord, increased FoxP3+ Tregs and improved recovery. Similarly, passive induction of EAE in mice by adoptive transfer of Th17 CD4+ T cells with an expression knockdown of GOT1 resulted in significantly reduced disease induction and severity 42. The diversion of α-ketoglutarate to 2-HG, away from the next stage of the TCA cycle (succinyl CoA), could also benefit Th17 CD4+ T cell differentiation by reducing the levels of OxPhos and ROS production 43. However, a recent study demonstrated that 2-HG blocked aerobic glycolysis in human T cells and induced a shift to OxPhos, with reduced lactate production, decreased expression of LDHA and PDHK1. 2-HG treatment in vitro increased the frequency of Tregs and decreased Th17 cell differentiation. Furthermore, AML patients with increased 2-HG levels due to IDH mutations exhibit reduced frequencies of Th17 CD4+ T cells in their peripheral blood 44. These contrasting results could be attributed to the species difference or on the permeability of the exogenous 2-HG utilized in these studies. Further, they may also reflect heterogeneity within Th17 CD4+ T cell populations, which can include subsets that co-express IL-10 and exhibit non-inflammatory properties, or those that co-produce both IFN-γ and IL-17 and exhibit substantially higher anti-tumor or pro-inflammatory potential. In support of this, Th17 CD4+ T cells that co-produce IFN-γ and IL-17 were found to possess a greater dependency on glutaminolysis relative to single-cytokine producing Th1 and Th17 CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, this subset contained significantly higher levels of NAD+ and Sirt1 (NAD+ dependent protein deacetylase) activity 45.

Several additional signaling proteins and transcription factors critically fine-tune the metabolic shifts in pro-inflammatory and pathologic Th17 CD4+ T cell responses. For example, IL-23 signals have been implicated as the deciding factor in the generation of pathogenic Th17 CD4+ T cells, in part by downregulating the expression of a scavenger receptor, CD5L. Consequently, CD5L−/− mice had exacerbated EAE in comparison to control mice. Vector-enforced expression of CD5L in a passive T cell transfer model of EAE resulted in reduced disease severity, even when the T cells were stimulated with IL-23 prior to transfer. CD5L expression alters the lipid profile of Th17 CD4+ T cells, increasing cellular cholesterol levels while decreasing polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFAs) levels, resulting in altered endogenous RORγt agonist availability and thus, RORγt binding targets. Supplementing Th17 CD4+ T cell cultures with PUFAs limited the development of pathogenic Th17 cells, even in the presence of IL-23 46.

The bioenergetics pathways employed by Th17 CD4+ T cells are also context dependent and modified by environmental factors. For example, mice on high fat diet have higher frequencies of Th17 CD4+ T cells and exhibit an increased susceptibility autoimmune disease severity, such as that in EAE or DSS-induced colitis is exacerbated in obese mice 47,48. Th17 CD4+ T cells from obese mice have enhanced expression of acetyl CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) and other FA metabolism genes. Inhibition or deletion of ACC1 results in reduced Th17 cell differentiation both in vitro and in vivo, and is associated with reduced severity in an EAE model 47,49. In particular, Th17 CD4+ T cells were found to exhibit a greater dependency on the activation of the glycolytic-lipogenic pathways, shuttling carbon molecules derived from glucose into the de novo FAS pathway via citrate and the TCA cycle. Inhibition of ACC1 reduced the dependency on de novo FAS and increased the uptake of external fatty acids, both of which are features of Tregs 49. ACC1 deletion also impairs the function of RORγt, preventing it from binding to the locus of and activating the transcription of Il17a and Il23r. However, addition of oleic acid to the medium restored RORγt function 47. Furthermore, inhibition of ACC1 expression by plant-derived PPARγ agonist Madecassic acid ameliorated DSS-induced intestinal inflammation by enhancing Treg responses and IL-10 production 50. ACC1-deletion also impaired Th1 CD4+ T cell responses, but not Tregs, in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection model, resulting in elevated bacterial load 51, suggesting that this may not be specific to Th17 CD4+ T cells.

Th17 CD4+ T cell differentiation and function is also particularly sensitive to amino acid starvation as compared to other T cell subsets. Deficiencies in cellular amino acids result in increasing levels of uncharged tRNAs, which then activates GCN2 and subsequently ATF4 and the AAR. Halofuginone, a small molecule inhibitor of collagen type 1 synthesis, activated the AAR in T cells and impaired Th17 CD4+ T cell differentiation and ameliorated autoimmunity in an EAE mouse model 52. However, the role of ATF4 is likely complex and context-dependent, as these results contrast a study discussed above where Th17 differentiation was enhanced by ATF4 deletion 17. Hypoxia is another critical modifier of the metabolic program of Th17 CD4+ T cells, and hypoxic conditions favor the differentiation of Th17 CD4+ T cells through the transcriptional regulator HIF-1α. Among activated T cells subsets, Th17 CD4+ T cells express the highest levels of HIF-1α and deletion of HIF-1α in T cells leads to impaired in vitro Th17 differentiation with reductions in IL-17, IL-22, RORγt and IL-23R 53,54. Reciprocally, there was an increase in FoxP3 expression in HIF-1α-deficient T cells, as HIF-1α targets FoxP3 for proteasomal degradation. It is proposed that HIF-1α enforces Th17 differentiation over Tregs by inducing glycolysis-associated gene expression, and blocking glycolysis with 2-DG limited Th17 differentiation 55. Subsequently, mice deficient in HIF-1α are resistant to EAE disease with reduced cellular infiltration into the spinal cord and increased numbers of Tregs in the central nervous system and peripheral immune organs 54,55. A major regulator of HIF-1α expression is mTOR, which acts a balancing point between Th17 CD4+ T cell and Treg differentiation. mTOR regulates the expression of proteins not just in the glycolytic pathway but also in PPP, FAO and mitochondrial biogenesis. Th17 CD4+ T cell differentiation is impaired by mTORC1 blockade, while blocking mTORC2 does not 19. The impact of mTOR activity on T cell differentiation is comprehensively reviewed in 18,56.

Despite these advances on understanding the bioenergetics pathways employed by Th17 CD4+ T cells, the metabolic dependencies of ILC3 are still largely unexplored (Figure 3). ILC3 resemble Th17 CD4+ T cells in transcription factor and effector cytokine expression, yet exhibit substantially more cellular heterogeneity and functionality. RNA-sequencing analyses of intestinal ILC3 in naïve mice revealed enrichment of transcripts associated with glycolysis (Hk2, Hk3, enolase-1 and phosphofructokinase), as well as metabolism of fructose/mannose, galactose and pyruvate 27. Currently, one study demonstrates that ILC3s in the intestine uptake FAs from the environment, but the significance of this phenomenon is yet to be determined 34. Furthermore, ILC3 and IL-22 can influence lipid metabolisms and transport in intestinal epithelial cells 57,58. Inhibition of ectonucleotidases, specifically CD39 (NTPDase1) and NTPDase3, in mice reduced the accumulation of ILC3s and decreased CD39 expression on ILC3s in the context of intestinal inflammation. Also in vitro stimulation of ILC3s with excess eATP, the target of CD39, inhibited IL-22 production from ILC3s, in an unknown mechanism 59. Substantial additional investigation is needed to determine whether primary and context-dependent bioenergetics pathways employed by ILC3 during development, homeostasis and function.

Regulatory T cells.

As stated earlier, freshly isolated human Tregs have high glycolytic potential due to elevated mTORC1 activity, low phosphorylated AMPK levels and are hypo-responsive to TCR stimuli. This anergic state is maintained by the mTOR dependent leptin production, which constrains Treg function 37,60. In activated murine Tregs, FoxP3 induces the shift to OxPhos while blocking glycolysis (by suppressing Myc) and favoring the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate 61. However, Treg migration depends on glycolysis induced via CD28 signals to upregulate glucokinase (GCK) via mTORC2. Deletion of GCK or Rictor impaired the migration of Tregs to skin grafts, resulting in graft rejection 62. A Treg specific Cdc42 deletion also led to an increase in glycolysis and FAO associated genes, thus reducing induced-Treg development 40

Tregs thrive under glutamine deficient conditions. In corroboration with studies mentioned earlier in this review, Klysz et al determined that the proliferation, suppressive activity and stability of FoxP3+ Tregs is enhanced under glutamine-deprived culture conditions and occurs through an endogenous TGF-β-dependent mechanism. Further, Tregs cultured under glutamine-deprived conditions exhibited an enhanced ability to suppress a T cell-dependent mouse model of intestinal inflammation. However, addition of a-ketoglutarate (cell permeable dimethyl KG) increased T-bet expression and mTORC1 activity, and reduced FoxP3+ Tregs 63. Disruption of mTORC1 activity (by Raptor deficiency) in FoxP3+ cells resulted in loss of suppressive functions and severe spontaneous autoimmune disease, Raptor-deficient Tregs exhibited reduced cholesterol and lipid biosynthesis which perturbed Treg suppressive activity. However, addition of mevalonate, a metabolite in the cholesterol synthesis pathway restored functional fitness as well as expression of CTLA and ICOS 64.

Carnitine palmitoyl-transferase-1 (CPT1), the rate limiting enzyme for FAO, is also highly expressed in Tregs and blocking CPT1 impairs in vitro Treg differentiation 36,37. CPT1 transfers the acyl group from fatty acid-acyl CoA to carnitine, which can then be shuttled into the mitochondria and converted back to fatty acid acyl-CoA for FAO to generate acetyl-CoA 65. Butyrate, a short chain FA produced by commensal microbes, supports Treg generation in vivo and in vitro by increasing the histone acetylation levels at the Foxp3 locus through the inhibition of histone deacetylases. When fed a diet rich in butyrate, mice exhibit enhanced Treg differentiation and reduced inflammation in a T cell transfer model of colitis, which was reversed when Tregs were depleted 66. Treg-specific deletion of LKB1, an AMPK regulator, also leads to a dramatic inflammatory phenotype, characterized by leukocyte infiltration into multiple organs, splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. LKB1 deficient Tregs exhibited decreased suppressor functions, reduced oxidative phosphorylation potential and ROS production, presenting a metabolic profile typically associated with Th17 CD4+ T cells 67,68. Both LKB1- or AMPK-deficient CD4+ T cells have enhanced mTORC1 activity and glycolysis but reduced lipid oxidation 69. While these effects were not specially analyzed in FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells, the metabolic profile presented highlights the importance of the AMPK-LKB axis in Treg development or function.

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) recognizes xenobiotic compounds such those derived from tryptophan catabolism (kynurenine) or synthetic pollutants (dioxin) and can influence Treg generation 70. Intestinal Tregs expressed the highest levels of AHR and Treg specific deletion of AHR reduced the intestinal Treg population 71. Recently, Norisoboldine, a natural AHR agonist, was found to support Treg differentiation under hypoxic conditions and limit a mouse model of intestinal damage and inflammation. Norisoboldine reduced the glycolytic capacity of Tregs by reducing the expression of HK2, by reducing the levels of HIF-1α and SIRT1 protein levels. Reduction in SIRT1 levels also lead to a decrease in the level of repressive histone methylation (H3K9me3) at the Foxp3 locus 72. Interestingly, HIF-1α and AHR work in concert to maintain a glycolytic profile in type 1 regulatory (Tr1) T cells, which are FoxP3 negative IL-10 producing T cells. AHR also regulates CD39 expression and CD39, an ectonucleotidase, depletes eATP to promote in vitro Tr1 differentiation and function, as well as in EAE mouse models 73. AHR competes with to bind to the shared nuclear transporter of HIF-1α. Therefore, the increased Treg differentiation observed in HIF-1α-deficient mice could correspond with increased AHR activity. However, AHR activation can also promote Th17 differentiation and this dichotomy is dependent on the type of AHR ligand. Furthermore, AHR expression is enhanced in non-pathogenic TH17 CD4+ T cells, which implies a potential role for AHR in modulating protective responses 74–76.

Conclusions and future directions

Our understanding of the cell-intrinsic metabolic pathways governing the development, homeostasis and function of innate and adaptive lymphocytes is still in its infancy and many fundamental questions remain. For example, the role of signaling molecules in regulating metabolism need to be further defined to understand how the same moiety (i.e. mTORC1) can influence multiple metabolic phenotypes. Similarly, while effector CD4+ T cells are known accelerate their glycolytic capacity upon activation to meet the needs of rapid proliferation, the reason for the shift to aerobic glycolysis is yet to be determined.

As only a handful of studies have begun to explore the regulation of ILC bioenergetics, much work remains to be done to unravel the gene networks instructing metabolic programming in these populations. It will be intriguing to compare the shared versus unique features of ILC metabolism compared to their adaptive CD4+ T cell counterparts, potentially uncovering how much of metabolic programming is evolutionarily conserved between these lineages. While many transcriptional and functional similarities exist between these cell families, ILCs tend to accumulate in barrier regions (compared to T cell dominance in lymphoid tissue), are constantly exposed to stimuli from the microbiota, and therefore their metabolic profile might be more closely defined by location and nature of activating stimuli. Th1 CD4+ T cells and NK cells appear to share a similar metabolic profile, in that they both utilize predominantly glycolysis for their activated effector phase. This correlates well with the impact of glycolytic enzymes on the expression of IFN-γ, which is the primary effector molecule of both cell types. However, currently there are no studies analyzing the metabolic requirements of non-cytotoxic ILC1s, so it remains unclear how they fit into the NK versus Th1 metabolic program. However, since ILC1s also produce IFN-γ and transcriptome analysis indicate the presence of elevated mTOR activation, it could be assumed that the metabolic profile of ILC1s resemble that of both Th1 CD4+ T cells and NK cells. Th1 CD4+ T cells and NK cells play major roles in eradicating intracellular pathogen or viral infections and are needed to generate an effective anti-tumor response, despite functioning in glucose-deprived microenvironments. While IFN-γ production is dependent on glycolysis, other effector mechanisms such Granzyme and perforin secretion, Fas ligand or TRAIL expression might not affected thus maintaining cytotoxicity at these sites. Recent reports indicate that a subset of unconventional ILC1s also contribute to the anti-tumor response through IFN-γ, in addition to granzymes and TRAIL expression 77.

In the context of ILC2s, the metabolic profiles of ILCs share some similarities with CD4+ T cell counterpart. Non-activated ILC2s utilize OxPhos or FAO, similar to naïve Th2 cells. Upon cytokine-driven activation, ILC2s are capable of achieving high rates of both glycolysis and OxPhos, suggesting that additional signals (perhaps received in the tissue environment) may be critical for determining whether glycolysis or mitochondrial respiration becomes the dominant metabolic program employed by ILC2s in specific infectious or inflammatory context. Supporting this, it appears ILC2s preferentially require FAO to mediate intestinal immunity 34, but initial reports in lung inflammation suggest a more complex dynamic at play for ILC2 glycolysis in which changing the lung nutrient environment (though genetic manipulation of hypoxic factors or amino acid metabolite composition) has opposing effects on ILC2 glycolytic rate 31,32. Tissue localization of ILC2s exposes them to different environmental cues such as high nutrient availability and low oxygen in the intestines to high oxygen levels in the lung. Therefore, future studies are needed to unravel the complex effects that tissue localization and inflammatory stimuli have on ILC2 fuel choice. Furthermore, reports have demonstrated that ILC2 function is also affected by the presence of metabolites such as leukotrienes, retinoic acid, and prostaglandins, but how these cell-extrinsic metabolites alter cell-intrinsic ILC2 metabolism is yet to be determined 78,79.

The impact of cellular metabolism in ILC3s has yet to be comprehensively interrogated. ILC3s share transcriptional and cytokine production similarity to Th17 CD4+ T cells but function to maintain barrier integrity and control immune responses. A recurring theme with metabolomic studies on Th17 CD4+ T cells is the impact on Th17-induced chronic inflammation or autoimmunity. However, Th17 CD4+ T cells and ILC3s also play vital roles in maintaining homeostasis with commensal microbiota and in pro- versus anti-tumor responses 80,81, however the metabolic drivers of these responses are not yet defined. Transcriptome analysis indicates a glycolytic profile but ILC3s intake significant amounts of FA in the intestine, however the relevance of these observations is yet to determined. Alterations in cell extrinsic (environmental) metabolites such as retinoic acid, AHR ligands, and eATP modulate ILC3 development and function, but it has not yet been explored whether this directly impacts cellular metabolism. This will be particularly important to define in the context of several chronic disorders where ILC3 homeostasis is disrupted and may contribute to disease pathogenesis, such as IBD and HIV infection (10).

As the study of immuno-metabolism continues to grow, it highlights the need for improved technological advances in order to interrogate the metabolic programs of primary immune cells, which represents a greater experimental challenge than the study of in vitro manipulated cell lines. Currently, a caveat in many immuno-metabolism studies is an overreliance on gene expression analysis to infer conclusions about metabolic pathways in cells without accompanying functional evidence to demonstrate that those pathways are operational in the cell type. Beyond the limited examination of bioenergetics using the extracellular flux “Seahorse” technicality, use of liquid chromatography mass spectrometry to determine metabolite composition either ‘unbiasedly’ or ‘targeted’ toward specific classes of metabolites is essential to draw meaningful conclusions about fuel choice in immune cell lineages. Unfortunately, the use of this methodology is problematic for primary immune cells as it requires tens of millions of cells, a significant technological hurdle that currently precludes analysis of primary immune cells like ILCs without employing cytokine-mediated cell expansion protocols 31. As a further caveat, interpretation of these types of mass spectrometry studies is complicated by the inability to distinguish the directionality of metabolite flux, since only the pool size is determined. Use of heavy isotope labeled metabolites to ‘trace’ the downstream metabolic products within a cell is critical to fully elucidate the metabolic flux of nutrients within immune cells. While wider adoption of these methods by the immunological community will greatly strengthen the metabolic, biological interpretation of these studies is complicated by the fact that the cells themselves have been subjected to in vitro culture and therefore are far removed from the tissue micro-environmental signals that have influenced their metabolic program. Intriguingly, new technologies that combine mass spectrometry detection of metabolites with histological mapping of cellular tissue localization, such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI), may hold the key to refining our understanding of how nutrient bioavailability within tissue may impact immune cell metabolism.

Taken all together, it is anticipated that additional research leveraging these technologies this area may help advance our understanding of how to manipulate immune cell metabolism for therapeutic advantage, thereby aiding in our ability to develop the next generation of immune-modulatory therapies that can boost immunity to pathogens or tumors, or conversely dampen pathologic immune-mediated diseases. Greater knowledge of the conserved versus unique metabolic programs employed by each subtype of ILCs and CD4+ T cells during the context of disease may represent new opportunities for targeted cellular manipulation with small molecules that shift metabolic programs to benefit human health.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Sonnenberg and Monticelli Laboratories for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the Sonnenberg Laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (DP5OD012116, R01AI123368, R21DK110262 and U01AI095608), the NIAID Mucosal Immunology Studies Team (MIST), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, the Searle Scholars Program, the American Asthma Foundation Scholar Award, Pilot Project Funding from the Center for Advanced Digestive Care (CADC), an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a Cancer Research Institute CLIP grant, the Meyer Cancer Center Collaborative Research Initiative, and the Roberts Institute for Research in IBD. Research in the Monticelli Laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health (F32AI134018), the NIAID Mucosal Immunology Studies Team (MIST), and the Weill Cornell Medicine Pre-Career Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Geltink RIK, Kyle RL, Pearce EL. Unraveling the Complex Interplay Between T Cell Metabolism and Function. Annu Rev Immunol 2018;36:461–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med 2015;212(9):1345–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida L, Lochner M, Berod L, Sparwasser T. Metabolic pathways in T cell activation and lineage differentiation. Semin Immunol 2016;28(5):514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumitru C, Kabat AM, Maloy KJ. Metabolic Adaptations of CD4(+) T Cells in Inflammatory Disease. Front Immunol 2018;9:540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu J, Paul WE. Peripheral CD4+ T-cell differentiation regulated by networks of cytokines and transcription factors. Immunol Rev 2010;238(1):247–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517(7534):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spits H, Bernink JH, Lanier L. NK cells and type 1 innate lymphoid cells: partners in host defense. Nat Immunol 2016;17(7):758–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duerr CU, Fritz JH. Regulation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Cytokine. 2016;87:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klose CS, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol 2016;17(7):765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells in the initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. Nat Med 2015;21(7):698–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnenberg GF, Mjosberg J, Spits H, Artis D. SnapShot: innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2013;39(3):622–622 e621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr., et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153(6):1239–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng M, Yin N, Chhangawala S, Xu K, Leslie CS, Li MO. Aerobic glycolysis promotes T helper 1 cell differentiation through an epigenetic mechanism. Science. 2016;354(6311):481–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J 2009;417(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franchina DG, Dostert C, Brenner D. Reactive Oxygen Species: Involvement in T Cell Signaling and Metabolism. Trends Immunol 2018;39(6):489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahnke J, Schumacher V, Ahrens S, et al. Interferon Regulatory Factor 4 controls TH1 cell effector function and metabolism. Sci Rep 2016;6:35521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, Xia R, Yue C, et al. ATF4 Regulates CD4(+) T Cell Immune Responses through Metabolic Reprogramming. Cell Rep 2018;23(6):1754–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waickman AT, Powell JD. mTOR, metabolism, and the regulation of T-cell differentiation and function. Immunol Rev 2012;249(1):43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgoffe GM, Pollizzi KN, Waickman AT, et al. The kinase mTOR regulates the differentiation of helper T cells through the selective activation of signaling by mTORC1 and mTORC2. Nat Immunol 2011;12(4):295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang K, Shrestha S, Zeng H, et al. T cell exit from quiescence and differentiation into Th2 cells depend on Raptor-mTORC1-mediated metabolic reprogramming. Immunity. 2013;39(6):1043–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keppel MP, Saucier N, Mah AY, Vogel TP, Cooper MA. Activation-specific metabolic requirements for NK Cell IFN-gamma production. J Immunol 2015;194(4):1954–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol 2014;15(8):749–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnelly RP, Loftus RM, Keating SE, et al. mTORC1-dependent metabolic reprogramming is a prerequisite for NK cell effector function. J Immunol 2014;193(9):4477–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, Macintyre AN, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell. 2015;162(6):1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velasquez SY, Killian D, Schulte J, Sticht C, Thiel M, Lindner HA. Short Term Hypoxia Synergizes with Interleukin 15 Priming in Driving Glycolytic Gene Transcription and Supports Human Natural Killer Cell Activities. J Biol Chem 2016;291(25):12960–12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assmann N, O’Brien KL, Donnelly RP, et al. Srebp-controlled glucose metabolism is essential for NK cell functional responses. Nat Immunol 2017;18(11):1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gury-BenAri M, Thaiss CA, Serafini N, et al. The Spectrum and Regulatory Landscape of Intestinal Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Shaped by the Microbiome. Cell. 2016;166(5):1231–1246 e1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker JA, McKenzie ANJ. TH2 cell development and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2018;18(2):121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JQ, Kalim KW, Li Y, et al. RhoA orchestrates glycolysis for TH2 cell differentiation and allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137(1):231–245 e234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Licona-Limon P, Kim LK, Palm NW, Flavell RA. TH2, allergy and group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol 2013;14(6):536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monticelli LA, Buck MD, Flamar AL, et al. Arginase 1 is an innate lymphoid-cell-intrinsic metabolic checkpoint controlling type 2 inflammation. Nat Immunol 2016;17(6):656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, Li D, Zhang X, et al. E3 Ligase VHL Promotes Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Maturation and Function via Glycolysis Inhibition and Induction of Interleukin-33 Receptor. Immunity. 2018;48(2):258–270 e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bando JK, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Identification and distribution of developing innate lymphoid cells in the fetal mouse intestine. Nat Immunol 2015;16(2):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelm C, Harrison OJ, Schmitt V, et al. Critical role of fatty acid metabolism in ILC2-mediated barrier protection during malnutrition and helminth infection. J Exp Med 2016;213(8):1409–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noack M, Miossec P. Th17 and regulatory T cell balance in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13(6):668–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michalek RD, Gerriets VA, Jacobs SR, et al. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J Immunol 2011;186(6):3299–3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Procaccini C, Carbone F, Di Silvestre D, et al. The Proteomic Landscape of Human Ex Vivo Regulatory and Conventional T Cells Reveals Specific Metabolic Requirements. Immunity. 2016;44(2):406–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Nichols AG, et al. Metabolic programming and PDHK1 control CD4+ T cell subsets and inflammation. J Clin Invest 2015;125(1):194–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franchi L, Monteleone I, Hao LY, et al. Inhibiting Oxidative Phosphorylation In Vivo Restrains Th17 Effector Responses and Ameliorates Murine Colitis. J Immunol 2017;198(7):2735–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalim KW, Yang JQ, Li Y, Meng Y, Zheng Y, Guo F. Reciprocal Regulation of Glycolysis-Driven Th17 Pathogenicity and Regulatory T Cell Stability by Cdc42. J Immunol 2018;200(7):2313–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kono M, Yoshida N, Maeda K, Tsokos GC. Transcriptional factor ICER promotes glutaminolysis and the generation of Th17 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(10):2478–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu T, Stewart KM, Wang X, et al. Metabolic control of TH17 and induced Treg cell balance by an epigenetic mechanism. Nature. 2017;548(7666):228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi J, Zuo H, Ni L, et al. An IDH1 mutation inhibits growth of glioma cells via GSH depletion and ROS generation. Neurol Sci 2014;35(6):839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bottcher M, Renner K, Berger R, et al. D-2-hydroxyglutarate interferes with HIF-1alpha stability skewing T-cell metabolism towards oxidative phosphorylation and impairing Th17 polarization. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(7):e1445454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chatterjee S, Daenthanasanmak A, Chakraborty P, et al. CD38-NAD(+)Axis Regulates Immunotherapeutic Anti-Tumor T Cell Response. Cell Metab 2018;27(1):85–100 e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C, Yosef N, Gaublomme J, et al. CD5L/AIM Regulates Lipid Biosynthesis and Restrains Th17 Cell Pathogenicity. Cell. 2015;163(6):1413–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Endo Y, Asou HK, Matsugae N, et al. Obesity Drives Th17 Cell Differentiation by Inducing the Lipid Metabolic Kinase, ACC1. Cell Rep 2015;12(6):1042–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng L, Jin H, Qiang Y, et al. High fat diet exacerbates dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis through disturbing mucosal dendritic cell homeostasis. Int Immunopharmacol 2016;40:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berod L, Friedrich C, Nandan A, et al. De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory T and T helper 17 cells. Nat Med 2014;20(11):1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu X, Wang Y, Wei Z, et al. Madecassic acid, the contributor to the anti-colitis effect of madecassoside, enhances the shift of Th17 toward Treg cells via the PPARgamma/AMPK/ACC1 pathway. Cell Death Dis 2017;8(3):e2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuve P, Minarrieta L, Erdmann H, et al. De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis During Mycobacterial Infection Is a Prerequisite for the Function of Highly Proliferative T Cells, But Not for Dendritic Cells or Macrophages. Front Immunol 2018;9:495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sundrud MS, Koralov SB, Feuerer M, et al. Halofuginone inhibits TH17 cell differentiation by activating the amino acid starvation response. Science. 2009;324(5932):1334–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Budda SA, Girton A, Henderson JG, Zenewicz LA. Transcription Factor HIF-1alpha Controls Expression of the Cytokine IL-22 in CD4 T Cells. J Immunol 2016;197(7):2646–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146(5):772–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, et al. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med 2011;208(7):1367–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang R, Solt LA. Metabolism of murine TH 17 cells: Impact on cell fate and function. Eur J Immunol 2016;46(4):807–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Kuang Z, Yu X, Ruhn KA, Kubo M, Hooper LV. The intestinal microbiota regulates body composition through NFIL3 and the circadian clock. Science. 2017;357(6354):912–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mao K, Baptista AP, Tamoutounour S, et al. Innate and adaptive lymphocytes sequentially shape the gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2018;554(7691):255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crittenden S, Cheyne A, Adams A, et al. Purine metabolism controls innate lymphoid cell function and protects against intestinal injury. Immunol Cell Biol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Procaccini C, De Rosa V, Galgani M, et al. An oscillatory switch in mTOR kinase activity sets regulatory T cell responsiveness. Immunity. 2010;33(6):929–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angelin A, Gil-de-Gomez L, Dahiya S, et al. Foxp3 Reprograms T Cell Metabolism to Function in Low-Glucose, High-Lactate Environments. Cell Metab 2017;25(6):1282–1293 e1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kishore M, Cheung KCP, Fu H, et al. Regulatory T Cell Migration Is Dependent on Glucokinase-Mediated Glycolysis. Immunity. 2018;48(4):831–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klysz D, Tai X, Robert PA, et al. Glutamine-dependent alpha-ketoglutarate production regulates the balance between T helper 1 cell and regulatory T cell generation. Sci Signal. 2015;8(396):ra97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng H, Yang K, Cloer C, Neale G, Vogel P, Chi H. mTORC1 couples immune signals and metabolic programming to establish T(reg)-cell function. Nature. 2013;499(7459):485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qu Q, Zeng F, Liu X, Wang QJ, Deng F. Fatty acid oxidation and carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: emerging therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Death Dis 2016;7:e2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang K, Blanco DB, Neale G, et al. Homeostatic control of metabolic and functional fitness of Treg cells by LKB1 signalling. Nature. 2017;548(7669):602–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He N, Fan W, Henriquez B, et al. Metabolic control of regulatory T cell (Treg) survival and function by Lkb1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(47):12542–12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacIver NJ, Blagih J, Saucillo DC, et al. The liver kinase B1 is a central regulator of T cell development, activation, and metabolism. J Immunol 2011;187(8):4187–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, Bradfield CA. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2010;185(6):3190–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye J, Qiu J, Bostick JW, et al. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Preferentially Marks and Promotes Gut Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep 2017;21(8):2277–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lv Q, Wang K, Qiao S, et al. Norisoboldine, a natural AhR agonist, promotes Treg differentiation and attenuates colitis via targeting glycolysis and subsequent NAD(+)/SIRT1/SUV39H1/H3K9me3 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis 2018;9(3):258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mascanfroni ID, Takenaka MC, Yeste A, et al. Metabolic control of type 1 regulatory T cell differentiation by AHR and HIF1-alpha. Nat Med 2015;21(6):638–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467(7318):967–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baricza E, Tamasi V, Marton N, Buzas EI, Nagy G. The emerging role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the activation and differentiation of Th17 cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016;73(1):95–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ho PP, Steinman L. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a regulator of Th17 and Treg cell development in disease. Cell Res 2008;18(6):605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dadi S, Chhangawala S, Whitlock BM, et al. Cancer Immunosurveillance by Tissue-Resident Innate Lymphoid Cells and Innate-like T Cells. Cell. 2016;164(3):365–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilhelm C, Kharabi Masouleh S, Kazakov A. Metabolic Regulation of Innate Lymphoid Cell-Mediated Tissue Protection-Linking the Nutritional State to Barrier Immunity. Front Immunol 2017;8:1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Konya V, Mjosberg J. Lipid mediators as regulators of human ILC2 function in allergic diseases. Immunol Lett 2016;179:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bailey SR, Nelson MH, Himes RA, Li Z, Mehrotra S, Paulos CM. Th17 cells in cancer: the ultimate identity crisis. Front Immunol 2014;5:276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mattner J, Wirtz S. Friend or Foe? The Ambiguous Role of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Cancer Development. Trends Immunol 2017;38(1):29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]