Atomic-level structure engineering potentially revolutionizes the design of capacitive oxide materials.

Abstract

Atomic-level structure engineering can substantially change the chemical and physical properties of materials. However, the effects of structure engineering on the capacitive properties of electrode materials at the atomic scale are poorly understood. Fast transport of ions and electrons to all active sites of electrode materials remains a grand challenge. Here, we report the radical modification of the pseudocapacitive properties of an oxide material, ZnxCo1−xO, via atomic-level structure engineering, which changes its dominant charge storage mechanism from surface redox reactions to ion intercalation into bulk material. Fast ion and electron transports are simultaneously achieved in this mixed oxide, increasing its capacity almost to the theoretical limit. The resultant ZnxCo1−xO exhibits high-rate performance with capacitance up to 450 F g−1 at a scan rate of 1 V s−1, competing with the state-of-the-art transition metal carbides. A symmetric device assembled with ZnxCo1−xO achieves an energy density of 67.3 watt-hour kg−1 at a power density of 1.67 kW kg−1, which is the highest value ever reported for symmetric pseudocapacitors. Our finding suggests that the rational design of electrode materials at the atomic scale opens a new opportunity for achieving high power/energy density electrode materials for advanced energy storage devices.

INTRODUCTION

A breakthrough in the development of efficient, safe, and sustainable energy storage devices for portable electronic devices, electrical vehicles, and stationary grid storage is urgently needed (1, 2). Supercapacitors have become one of the most promising energy storage systems (3–16), owing to their high power density, rapid charging-discharging rate, and long cyclic stability. However, the widespread application of supercapacitors is severely limited because of intrinsically low energy density of the extensively studied carbon-based electrochemical double-layer capacitors. Recently, supercapacitors that store energy through ion intercalation into bulk electrode materials, similar to what is seen in lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), have been intensively studied (6–9, 14, 17–19). The alluring feature of this kind of supercapacitors is the promising prospect toward enhancing energy density without compromising the high power density.

Very recently, the cost-effective transition metal oxides and perovskite oxides have shown great potential in ion (cation or anion) intercalation-type supercapacitor applications (6–9, 20–22). Despite great advances, the practical application of these oxide materials is still limited by their dissatisfactory rate capability, limited potential window, and low energy density (6, 8, 9). These limitations of oxide electrode materials are mainly due to the sluggish ion transport kinetics (8, 9). Nanoengineering offers a novel and exciting opportunity to tackle these problems by shortening the ion transport paths and relaxing the strain generated during electrochemical cycling (8, 9). These investigations indicate the opportunity of controlling the mode of charge storage by engineering proper nanostructures. However, the understanding of the ion diffusion control by atomic structure is still missing.

The inherently low electrical conductivity is another reason for the limited performance of oxide materials (23). Previous reports suggest that doping metal or nonmetal elements into the host oxides is an effective route to enhance their electrical conductivity (24), which is beneficial for achieving high energy density. Unfortunately, doping did not produce notable improvement in electrochemical performance. Even worse, it usually sacrifices the power density, which is possibly due to the nonuniform distribution of transition metal ions within oxides. Therefore, fast transport of ions and electrons to all active sites (interior and exterior) in oxide electrodes is of crucial significance for their performance, but it is still a grand challenge.

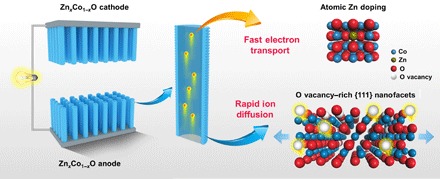

Atomic-level structure engineering can give rise to substantial modification of the chemical and physical properties of materials, which has been demonstrated with great success in the field of catalysis (25–27). So far, the atomic-level engineering and understanding of the capacitive oxide electrodes are largely missing. Here, we report the radical modification of the pseudocapacitive properties of an oxide material, ZnxCo1−xO, via atomic structure engineering, which changes its dominant charge storage mechanism from surface redox reactions to ion intercalation into bulk material. On the basis of the experimental observations, cutting edge characterization, and theoretical calculations, we demonstrate that atomic-level engineering endows ZnxCo1−xO electrodes with both rapid ionic and electronic conductivity (Fig. 1). The creation of oxygen (O) vacancy–rich {111} nanofacets enables easy oxygen-ion intercalation into this oxide with a low energy barrier, and the atomically uniform Zn doping assures a considerable improvement of its electrical conductivity respective to pristine CoO. As a result, the ZnxCo1−xO electrode exhibits high-rate performance with capacitance up to 450 F g−1 at a scan rate of 1 V s−1, reaching the performance of the state-of-the-art transition metal carbides. A symmetric device assembled with ZnxCo1−xO achieves an energy density of 67.3 watt-hour (Wh) kg−1, which is the highest among symmetric pseudocapacitors consisting of metal oxides, metal sulfides, and other two-dimensional transition metal carbides.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the atomic-level structure engineering of ZnxCo1−xO for high-rate intercalation pseudocapacitance applications.

Arrays of single-crystal ZnxCo1−xO nanorods (NRs) are in situ fabricated on a conductive substrate to ensure quick charge transportation. For every single ZnxCo1−xO NR, the uniform doping of Zn ions in the oxide host assures fast electrical conduction, while the creation of O vacancy–rich {111} nanofacets enables easy access of oxygen ions into the oxide host with a low energy barrier.

RESULTS

Atomic structure engineering of ZnxCo1−xO NRs

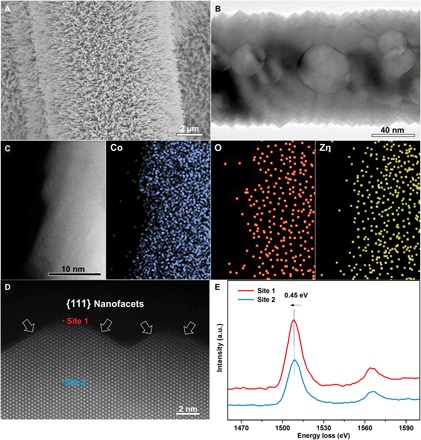

We fabricated arrays of ZnxCo1−xO NRs in situ on carbon fiber paper (CFP) (Fig. 2A) by a cation exchange method (28) using ZnO NRs as sacrificial templates. This specific method enables atomically uniform Zn doping in the CoO host lattice. In traditional chemical methods, heteroatoms are generally introduced into host materials by dopant precursor incorporation during their growth. However, these methods offer poor stoichiometric and dopant distribution. In our method, we achieved the synthesis of ZnxCo1−xO NRs by the replacement reaction of Co2+ for Zn2+ ions, which proceeds through inward diffusion of Co2+ and outward diffusion of Zn2+ (fig. S1). This bidirectional diffusion and similar radii of Co2+ and Zn2+ allow easy formation of a ZnxCo1−xO solid solution with a single-crystal structure (Fig. 2B and figs. S2 and S3). The molar ratio of Zn2+ and Co2+ in the resultant ZnxCo1−xO NRs can be easily tuned by controlling the cation exchange temperature (table S1 and figs. S3 and S4). The subnanometer spatial resolution elemental mapping shows that Co, O, and Zn elements are uniformly distributed across a single ZnxCo1−xO NR (Fig. 2C and fig. S5), demonstrating that after the cation exchange process, the residual Zn2+ ions are well integrated into the CoO lattice, resulting in substitutional Zn2+ doping in CoO at the atomic level.

Fig. 2. Characterization of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

(A) Typical scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of ZnxCo1−xO NR arrays distributed on CFP. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of an individual ZnxCo1−xO NR. (C) Elemental mapping of Co, O, and Zn on a single ZnxCo1−xO NR. (D) Atomic-resolution high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF)–scanning TEM (STEM) image of the surface, which is enclosed with {111} nanofacets. (E) EELS Co-L2,3 spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NR collected at two specific sites (site 1 and site 2) as indicated in (D), where a 0.45-eV peak shift toward the low energy loss direction is evident in site 1 respective to that in site 2. The data presented in this figure refer to Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs. a.u., arbitrary units.

Moreover, the cation exchange method renders ZnxCo1−xO NRs with exposed {111} nanofacets (Fig. 2D and fig. S6), which accommodate large amounts of O vacancies on the near surface region of the ZnxCo1−xO NRs (fig. S7). We discerned the spatial distribution of O vacancies on the ZnxCo1−xO NRs by electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS). Here, Co-L2,3 edge spectra, sensitive to the presence of O vacancies, were detected along the line from site 1 to site 2 on a single ZnxCo1−xO NR (Fig. 2D). The collected spectrum continuously shifts toward the high energy loss direction, indicating the gradual decrease of the amount of O vacancies, but no shift is noticed away from site 2 toward the interior of the ZnxCo1−xO NRs. The peak shift observed on the two spectra collected for site 1 and site 2 is ~0.45 eV (Fig. 2E). These results reveal that the O vacancies are mostly enriched below 2 to 3 nm from the outermost surface of the ZnxCo1−xO NRs with an average O vacancy concentration of ~22.5% (fig. S8 and note S1). Such high number of O vacancies induces 3 to 5% lattice expansion in the surface region of the ZnxCo1−xO NRs (fig. S9). As shown below, these atomic-level structural features, i.e., abundant O vacancies confined on the {111} nanofacets and atomically uniform Zn doping, result in fast ion and electron transports in the as-engineered ZnxCo1−xO NRs, which directly lead to the excellent capacitive performance.

Electrochemical properties of ZnxCo1−xO NRs

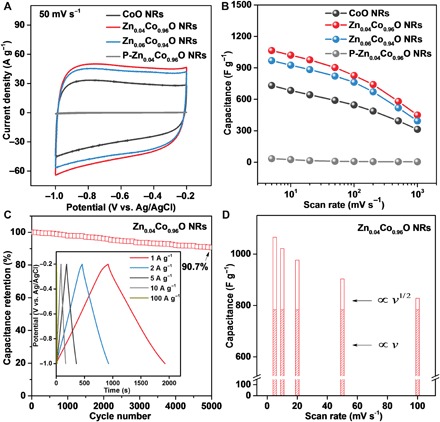

To understand the influence of the above atomic-level structural characteristics on the electrochemical behavior, we measured and compared the electrochemical properties of ZnxCo1−xO NRs (x = 0, x = 0.04, and x = 0.06) with those of polycrystalline ZnxCo1−xO (P-ZnxCo1−xO, x = 0.04) NRs (figs. S10 and S11). Figure 3A shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves collected at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 for a voltage window of 0.8 V [−1.0 to −0.2 V versus Ag/AgCl (VAg/AgCl)]. Notably, P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs exhibit typical redox pseudocapacitance in the potential range of −0.1 to 0.4 VAg/AgCl (fig. S12A). In the potential window studied, we only observed an electric double-layer capacitance in the case of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs (Fig. 3A, figs. S12B and S13, and note S2). Unexpectedly, ZnxCo1−xO NRs show nearly rectangular current-voltage curves, characteristic of an ideal pseudocapacitive response (Fig. 3A and fig. S14). Impressively, the maximum capacity of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs reaches as high as 1065 F g−1 at 5 mV s−1, which is nearly 31 times higher than that of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs. Given that the Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) surface area of ZnxCo1−xO NRs (~30 m2 g−1) is only one-third of that measured for P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs (~91 m2 g−1), the observed substantial capacity enhancement of ZnxCo1−xO NRs in comparison to P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs demonstrates a great feasibility to promote the charge storage of electrode materials through atomic structure engineering. The galvanostatic charge/discharge measurements with exceptional cycling stability further confirmed the excellent electrochemical performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs (Fig. 3C, figs. S15 and S16, and table S2).

Fig. 3. Electrochemical performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs as compared with P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

(A) CV curves at 50 mV s−1. (B) Specific capacity as a function of sweep rate between 5 and 1000 mV s−1. (C) Capacitance retention of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs by galvanostatic cycling at 10 A g−1, with the inset showing galvanostatic cycling profiles collected at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 100 A g−1. (D) Deconvolution of the charge contribution as a function of scan rates, indicating that Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs facilitate fast electrochemical reaction, resulting in higher capacity contributed dominantly from the v-dependent charge.

Besides high capacity, ZnxCo1−xO NRs exhibit exceptional rate performance. As shown in Fig. 3B, Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs preserve 55% of the capacitance following a 100-fold scan rate increase from 5 to 500 mV s−1. Even at 1 V s−1, they deliver a high capacity of up to 450 F g−1, competing with the state-of-the-art high-rate transition metal carbides (18). To shed light on the superior high-rate capability of ZnxCo1−xO NRs, we carried out an analysis of the peak current (i) dependence on the scan rate (v; fig. S17). In general, the peak current, i, is a combination of the capacitive effect (k1v) and diffusion-controlled intercalation (k2v1/2) according to (29)

| (1) |

where V is a fixed potential. By determining both k1 and k2, it is possible to identify the fraction of current contributed by capacitive processes and that originating from diffusion-controlled intercalation. The capacitive response of the Zn0.04Co0.96O electrode is nearly constant across a wide range of scan rates, from 5 to 100 mV s−1, contributing more than 74% to the total charge storage (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the diffusion-controlled capacity is a small portion of the entire capacitance. These collective results demonstrate excellent rate performance of the ZnxCo1−xO electrode, which can be ascribed to the fast ion and electron transports achieved in the as-engineered ZnxCo1−xO electrodes (see discussion below).

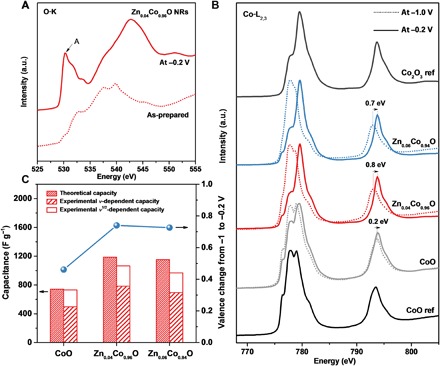

Charge storage mechanism in ZnxCo1−xO NRs

To provide further insight into the charge storage mechanism in ZnxCo1−xO NRs, we performed the synchrotron-based x-ray absorption (XAS) measurements (Fig. 4A and fig. S18). The O-K edge spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs before and after processing at −0.2 VAg/AgCl are shown in Fig. 4A. A comparison of these spectra reveals the insertion of oxygen ions into the ZnxCo1−xO NRs. Noticeably, peak A originates from the transition of electrons to hole states of Co3d–O2p octahedral coordination (30). For the as-prepared ZnxCo1−xO NRs, the intensity of peak A is weak due to the presence of a large amount of O vacancies. After processing the ZnxCo1−xO NRs at −0.2 VAg/AgCl, peak A gains intensity, indicating the increased oxygen content in the ZnxCo1−xO NRs. Accordingly, shifts toward high photon energy are evident in the Co-L2,3 edge spectra of the ZnxCo1−xO NRs after processing at −0.2 VAg/AgCl, indicating the oxidation of Co ions (Fig. 4B). The data fitting and analysis (fig. S19) reveal that the average Co oxidation state changes per Co atom in CoO, Zn0.04Co0.96O, and Zn0.06Co0.94O NRs are ~0.46, 0.74, and 0.72 ē, respectively (Fig. 4C). Using Faraday’s law, the maximum theoretical capacity for CoO, Zn0.04Co0.96O, and Zn0.06Co0.94O NRs can be estimated as 742, 1187, and 1153 F g−1, respectively (Fig. 4C and note S3), which are in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed capacities (Figs. 3B and 4C). Therefore, the capacitive charge storage occurs dominantly by oxidation of Co ions in the bulk ZnxCo1−xO through a mechanism of oxygen intercalation (note S4), which can be described as

| (2) |

where δ is the average oxygen vacancy concentration of ZnxCo1−xO NRs, and y is the mole fraction of inserted oxygen ions beyond stoichiometry. Notably, traditional transition metal oxides, such as RuO2, MnO2, and CoOx, mainly store charges through a surface redox mechanism (10). In our case, the atomic-level engineering activates the oxygen intercalation, which contributes to the improved charge storage in the as-engineered ZnxCo1−xO NRs. For Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs, the obtained capacity approaches its theoretical limit of 1267 F g−1 (note S3). The aforementioned oxygen intercalation mechanism assures the full use of the oxide electrode.

Fig. 4. Analysis of charge storage mechanism in ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

(A) O-K edge XAS spectra of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs before and processed at −0.2 VAg/AgCl. (B) Co-L2,3 edge XAS spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs collected at −1 and −0.2 VAg/AgCl. (C) Average Co oxidation state change (right) and the corresponding theoretical capacity (left) of ZnxCo1−xO NRs from −1 to −0.2 VAg/AgCl based on the Co-L2,3 edge spectra fitting. The experimental charge contributions of v- and v1/2-dependent capacity at 5 mV s−1 are shown for comparison (left).

Origin of high-rate oxygen intercalation capacitance in ZnxCo1−xO NRs

Since O vacancies are the active sites for oxygen-ion intercalation, high O vacancy mobility is crucial to facilitate fast oxygen-anion intercalation during charge storage (9). To gain further insight into the mobility of O vacancies in the as-engineered ZnxCo1−xO, we carried out the first-principle calculations (fig. S20). Our results reveal that the diffusion barrier of O vacancies in ZnxCo1−xO is sensitive to the surface geometrical structure. That is, O vacancies entering into the interior of ZnxCo1−xO through typical low-index {100} facets encounter a high-energy barrier of 1.82 eV (Fig. 5A), well explaining why traditional ZnxCo1−xO (P-ZnxCo1−xO) NRs exhibit negligible intercalation pseudocapacitance (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast, the energy barrier on {111} facets falls down to 1.05 eV, and a 3% lattice expansion even gives rise to a much lower activation energy barrier of ~0.70 eV. Therefore, the {111} nanofacets and tensile strain confined on the respective surface and near surface region of ZnxCo1−xO NRs provide advantageous geometrical environment for rapid diffusion of O vacancies. Moreover, the numerous nanopores inside ZnxCo1−xO NRs with well-defined {111} side faces greatly enhance the surface region of ZnxCo1−xO NRs (fig. S21), further facilitating the diffusion of O vacancies to all active sites inside ZnxCo1−xO NRs. Note that the isolated O vacancy diffusion should vary greatly from a high concentration on the surface of ZnxCo1−xO. The previous work (31) on the cation intercalation into oxides suggests that an increase in the concentration of diffusing cation results in a decrease in the diffusion barrier. A similar situation is in our case, where diffusion of O vacancies is greatly enhanced upon increasing the surface concentration of O vacancies (note S1). Consistent with the theoretical calculations, we observe a high oxygen diffusion rate up to 1.0 × 10−10 cm2 s−1 in CoO NRs (figs. S22 and S23), which is about one or two orders of magnitude higher than that observed in perovskite oxides (9), and even higher than the lithium diffusion rate in common lithium-ion intercalation materials (32).

Fig. 5. Computational investigations of oxygen ion diffusion and electrical conduction in ZnxCo1−xO.

(A) Migration activation energies of the O vacancy diffusing into bulk ZnxCo1−xO (x = 0) through {100}, {111}, and strained {111} facets (with 3% tensile strain), with the inset showing the O vacancy diffusion path. Color codes: blue and red spheres denote cobalt and oxygen atoms, respectively, and yellow spheres denote diffusing O vacancy. (B) The DOS on pristine and Zn-doped CoO. The arrow points out new electronic states, which appear in the bandgap of Zn-doped CoO, demonstrating the importance of atomic Zn2+ doping in promoting the electrical conduction in ZnxCo1−xO.

On the other hand, only fast oxygen-ion intercalation is insufficient to achieve this high intercalation capacity in ZnxCo1−xO NRs, which can be accomplished by simultaneous promotion of the electronic conductivity. As displayed by the calculated density of states (DOS) in Fig. 5B, the pristine CoO exhibits a wide bandgap of ~2.4 eV, indicating intrinsically poor electronic conductivity. For the Zn-doped CoO (ZnxCo1−xO), some new electronic states emerge in the bandgap (indicated by arrow in Fig. 5B). The enhanced DOS increase the carrier density in ZnxCo1−xO. This is supported by Mott-Schottky (M-S) measurements showing that the Zn-doped CoO NRs feature nearly 10-fold enhancement in charge carriers as compared with CoO NRs (fig. S24). This promotion of electronic conductivity leads directly to greatly increased capacitive charge storage in Zn-doped CoO NRs (Zn0.04Co0.96O and Zn0.06Co0.94O NRs) as compared with CoO NRs (Fig. 4C).

Thus, in the atomically engineered ZnxCo1−xO NRs, fast ion and electron transports are simultaneously achieved and synergistically combined to contribute to their superior performance. Following this atomic engineering route, it is predicted that further charge transport promotion in this oxide can lead to the capacity exceeding 2000 F g−1 (note S3) without sacrificing its power capability. This ideal oxide electrode could, in principle, be realized by multielement doping and/or by decreasing the crystal size of oxide.

Practical application of ZnxCo1−xO NRs in symmetric supercapacitors

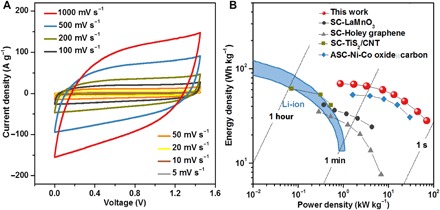

Electrode materials with large potential windows are highly preferable in practical storage devices. However, oxide electrodes are usually plagued by limited potential windows. ZnxCo1−xO NRs can also afford a high level of intercalation pseudocapacitance in the working potentials above 0 VAg/AgCl (fig. S25). Therefore, a symmetric cell composed of two ZnxCo1−xO NRs electrodes successfully extends the operating voltage window to nearly 1.5 V in aqueous electrolyte (Fig. 6A), much higher than those of the reported cobalt oxide-based electrodes (0.6 to 0.8 V) (33, 34). Figure 6B shows the specific power density and energy density of the as-fabricated device in comparison to traditional LIBs. As shown, ZnxCo1−xO NRs deliver a steady and high energy density over a wide range of power, presenting a high energy density of 67.3 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 1.67 kW kg−1, approaching the higher end of LIBs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest value among symmetric pseudocapacitors (table S3) consisting of metal oxides (9), metal sulfides (35), and other two-dimensional materials (36). Even at a high power density of 68.6 kW kg−1, the device still has an energy density of 27.6 Wh kg−1. Therefore, our work shows the possibility of atomic-level structure engineering of metal oxides to achieve a promising capacitive intercalation that presents both high power density and energy density.

Fig. 6. Electrochemical performance of symmetric supercapacitor device in aqueous electrolyte (6 M KOH).

(A) CV curves of our symmetric supercapacitor (SC) device at different scan rates. (B) Ragone plot of the SC device, data of traditional LIBs, some high-performance SCs (9, 35, 36), and asymmetric supercapacitor (ASC) (11) devices are also added for the purpose of comparison. Our SC device is assembled with Zn0.04Co0.96O NR electrodes as both cathode and anode.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated atomic-level structure engineering of a metal oxide for high-rate charge storage via oxygen intercalation. The combination of experiment and theoretical calculations shows that the excellent performance can be assigned to the simultaneously enhanced ionic diffusion and electronic conductivity in the as-engineered oxide studied. The confinement of abundant O vacancies on {111} nanofacets enables easy intercalation of oxygen ions into this oxide with a low energy barrier, and the atomically uniform Zn doping assures fast electrical conduction. We emphasize that the as-engineered oxide electrode exhibits high rate capability, a wide potential window, and high energy density, with its maximum capacity approaching the theoretical limit. We believe that this work will stimulate research toward atomic-level structure engineering of electrode materials, which can be used to design the next-generation high energy and high power electrochemical devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of ZnxCo1−xO NRs and P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs

In this work, the self-supported ZnxCo1−xO NR arrays were grown directly on CFP using a cation exchange method in the gas phase (37–39). ZnO NRs on CFP were used as sacrificial templates. The molar ratio of Zn2+ and Co2+ in the resultant ZnxCo1−xO NRs can be easily controlled by tuning the cation exchange temperature (table S1). P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs were fabricated on CFP using the hydrothermal method (40). Zinc nitrate [Zn(NO3)2] was chosen as the zinc dopant precursor, and the molar ratio of Zn2+ and Co2+ in the final P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs was tuned by tuning the mass ratio of Zn2+ and Co2+ in the precursors.

Structural characterizations

SEM and TEM characterizations were carried out using a Hitachi S-4800 SEM and a JEOL 2100 TEM, respectively. HAADF-STEM imaging was performed on a JEOL ARM200F microscope with a STEM aberration corrector operated at 200 kV. The BET surface area was determined from nitrogen adsorption data measured at 77 K on an ASAP 2020 physisorption analyzer (Micromeritics Inc., USA). The loading masses of ZnxCo1−xO and P-CoO NRs on CFP substrates were measured using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (NexION 300Q, PerkinElmer).

XAS measurements

XAS measurements were carried out at experimental station 8-2 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source. XAS data were recorded in fluorescence yield mode. ZnxCo1−xO electrodes were processed using CV. After five cycles with the scan rate of 10 mV s−1, the electrode was cycled at 5 mV s−1 to the required potential. The electrodes were then taken out from the electrolyte, washed with ethanol, dried using argon gas, and then sealed in tape to prevent exposure to the environment.

Electrochemical characterizations

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using a VersaSTAT 3 electrochemistry workstation from Princeton Applied Research. The tests were performed in a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell using oxide NR-loaded CFP as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode, and a Pt wire as the counter electrode in nitrogen gas saturated with 6 M KOH electrolyte. The capacitive property of CFP is provided in fig. S26. The loading amounts of CoO, Zn0.04Co0.96O, Zn0.06Co0.94O, and P-Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs on the CFP substrate were 0.322, 0.326, 0.356, and 0.335 mg cm−2, respectively. In the symmetric device testing, one ZnxCo1−xO NR electrode acted as the working electrode, and the other served as the counter electrode. The total loading mass of ZnxCo1−xO NRs on these two electrodes was 0.652 mg cm−2.

Computational methods

All density functional theory (DFT) computations were performed with the Hubbard-U framework (DFT + U) using the Vienna ab initio simulation package. The projector-augmented wave pseudopotential with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional was used in the computations. The Hubbard effective term Ueff(Co) = 3.7 eV was applied. The relevant details, references, and computational structural models (figs. S20 and S27) are given in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (51722103), the Natural Science Foundation of China (51571149 and 21576202), the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Guangdong Province (U1601216), and the Australian Research Council (ARC) through the Discovery Project program (FL170100154, DP170104464, and DP160104866). XAS measurements were carried out at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. The calculations were performed on TianHe-1A at the National Supercomputer Center, Tianjin. Author contributions: T.L. and S.-Z.Q. conceived the project and designed the experiments. T.L., P.D., and M.W. performed the experiments. T.L. and B.G. carried out the TEM characterization. X.Z. performed the soft XAS characterization. Z.H. and T.L. conducted the DFT calculations. All authors discussed the results and commented on or prepared the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/10/eaau6261/DC1

Fig. S1. Schematic diagram of the cation exchange methodology for the synthesis of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S2. TEM characterizations of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S3. X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S4. SEM images of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S5. Composition analysis of a single Zn0.04Co0.96O NR.

Fig. S6. HAADF-STEM characterization of the as-exchanged ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S7. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy O 1s spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S8. Schematic illustration of the spatial distribution of O vacancies in a single ZnxCo1−xO NR.

Fig. S9. Analysis of lattice expansion of the surface region of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S10. Characterization of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated directly on CFP.

Fig. S11. XRD spectrum of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated on CFP.

Fig. S12. CV curves of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S13. Atom arrangements on low index planes of CoO.

Fig. S14. CV curves of ZnxCo1−xO NRs collected at scan rates from 5 to 1000 mV s−1.

Fig. S15. XPS spectra of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs before and after the cycling test.

Fig. S16. Structural characterizations of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs after the cycling test.

Fig. S17. Deconvolution of diffusion-controlled and capacitive-like capacitance in ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S18. O-K edge x-ray absorption near-edge structure spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs before and processed at −0.2 VAg/AgCl.

Fig. S19. Analysis of Co-L2,3 edge XAS spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S20. Top-view and side-view illustration of O vacancy diffusion path through different surface facets.

Fig. S21. TEM image of an individual ZnxCo1−xO NR.

Fig. S22. Length distribution of ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated directly on CFP.

Fig. S23. Diffusion rate calculations for ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S24. M-S plots for ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S25. Electrochemical performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs as compared with P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S26. CV curve of carbon fiber paper.

Fig. S27. Simulation models of bulk CoO and Zn-doped CoO.

Table S1. Average O vacancy concentrations of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Table S2. Elemental analysis of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs before and after the cycling test.

Table S3. Comparative summary of the performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs in symmetric supercapacitor with the present symmetric supercapacitor and asymmetric supercapacitors.

Note S1. Analysis of the distribution of O vacancy on ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S2. Estimation of the theoretical capacitance of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S3. Estimation of the theoretical capacitance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S4. Analysis of the oxygen intercalation mechanism in ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Supplementary Methods

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Dunn B., Kamath H., Tarascon J.-M., Electrical energy storage for the grid: A battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Z., Zhang J., Kintner-Meyer M. C. W., Lu X., Choi D., Lemmon J. P., Liu J., Electrochemical energy storage for green grid. Chem. Rev. 111, 3577–3613 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu C.-C., Chang K.-H., Lin M.-C., Wu Y.-T., Design and tailoring of the nanotubular arrayed architecture of hydrous RuO2 for next generation supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 6, 2690–2695 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang X., Hirata A., Fujita T., Chen M., Nanoporous metal/oxide hybrid electrodes for electrochemical supercapacitors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 232–236 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toupin M., Brousse T., Bélanger D., Charge storage mechanism of MnO2 electrode used in aqueous electrochemical capacitor. Chem. Mater. 16, 3184–3190 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustyn V., Come J., Lowe M. A., Kim J. W., Taberna P.-L., Tolbert S. H., Abruña H. D., Simon P., Dunn B., High-rate electrochemical energy storage through Li+ intercalation pseudocapacitance. Nat. Mater. 12, 518–522 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brezesinski T., Wang J., Tolbert S. H., Dunn B., Ordered mesoporous α-MoO3 with iso-oriented nanocrystalline walls for thin-film pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 9, 146–151 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H.-S., Cook J. B., Lin H., Ko J. S., Tolbert S. H., Ozolins V., Dunn B., Oxygen vacancies enhance pseudocapacitive charge storage properties of MoO3−x. Nat. Mater. 16, 454–460 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mefford J. T., Hardin W. G., Dai S., Johnston K. P., Stevenson K. J., Anion charge storage through oxygen intercalation in LaMnO3 perovskite pseudocapacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 13, 726–732 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon P., Gogotsi Y., Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–854 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan B. Y., Kushima A., Yu L., Li S., Li J., Lou X. W., Coordination polymers derived general synthesis of multishelled mixed metal-oxide particles for hybrid supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605902 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan B. Y., Yu L., Wang X., Song S., Lou X. W., Formation of onion-like NiCo2S4 particles via sequential ion-exchange for hybrid supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605051 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi D., Blomgren G. E., Kumta P. N., Fast and reversible surface redox reaction in nanocrystalline vanadium nitride supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 18, 1178–1182 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukatskaya M. R., Mashtalir O., Ren C. E., Dall’Agnese Y., Rozier P., Taberna P. L., Naguib M., Simon P., Barsoum M. W., Gogotsi Y., Cation intercalation and high volumetric capacitance of two-dimensional titanium carbide. Science 341, 1502–1505 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugimoto W., Iwata H., Yokoshima K., Murakami Y., Takasu Y., Proton and electron conductivity in hydrous ruthenium oxides evaluated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy: The origin of large capacitance. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 7330–7338 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sassoye C., Laberty C., Khanh H. L., Cassaignon S., Boissière C., Antonietti M., Sanchez C., Block-copolymer-templated synthesis of electroactive RuO2-based mesoporous thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1922–1929 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kundu D., Adams B. D., Duffort V., Vajargah S. H., Nazar L. F., A high-capacity and long-life aqueous rechargeable zinc battery using a metal oxide intercalation cathode. Nat. Energy 1, 16119 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukatskaya M. R., Kota S., Lin Z., Zhao M.-Q., Shpigel N., Levi M. D., Halim J., Taberna P.-L., Barsoum M. W., Simon P., Gogotsi Y., Ultra-high-rate pseudocapacitive energy storage in two-dimensional transition metal carbides. Nat. Energy 2, 17105 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghidiu M., Lukatskaya M. R., Zhao M.-Q., Gogotsi Y., Barsoum M. W., Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide ‘clay’ with high volumetric capacitance. Nature 516, 78–81 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naoi K., Kurita T., Abe M., Furuhashi T., Abe Y., Okazaki K., Miyamoto J., Iwama E., Aoyagi S., Naoi W., Simon P., Ultrafast nanocrystalline-TiO2 (B)/carbon nanotube hyperdispersion prepared via combined ultracentrifugation and hydrothermal treatments for hybrid supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 28, 6751–6757 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu L., Liu Y., Su C., Zhou W., Liu M., Shao Z., Perovskite SrCo0.9Nb0.1O3−δ as an anion-intercalated electrode material for supercapacitors with ultrahigh volumetric energy density. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9576–9579 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai T., Sun S., Liu X., Liang C., Wang G., Xia H.. Achieving insertion-like capacity at ultrahigh rate via tunable surface pseudocapacitance. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706640 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park M., Zhang X., Chung M., Less G. B., Sastry A. M., A review of conduction phenomena in Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 195, 7904–7929 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Hasin P., Wu Y., NixCo3−xO4 nanowire arrays for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 22, 1926–1929 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C., Kang Y., Huo Z., Zhu Z., Huang W., Xin H. L., Snyder J. D., Li D., Herron J. A., Mavrikakis M., Chi M., More K. L., Li Y., Markovic N. M., Somorjai G. A., Yang P., Stamenkovic V. R., Highly crystalline multimetallic nanoframes with three-dimensional electrocatalytic surfaces. Science 343, 1339–1343 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ariga K., Ishihara S., Abe H., Atomic architectonics, nanoarchitectonics and microarchitectonics for strategies to make junk materials work as precious catalysts. CrystEngComm 18, 6770–6778 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abe H., Liu J., Ariga K., Catalytic nanoarchitectonics for environmentally compatible energy generation. Mater. Today 19, 12–18 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivest J. B., Jain P. K., Cation exchange on the nanoscale: An emerging technique for new material synthesis, device fabrication, and chemical sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 89–96 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A. J. Bard, L. R. Faulkner, Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications (Wiley, ed. 2, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karvonen L., Valkeapää M., Liu R.-S., Chen J.-M., Yamauchi H., Karppinen M., O-K and Co-L XANES study on oxygen intercalation in perovskite SrCoO3-δ. Chem. Mater. 22, 70–76 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yildirim H., Greeley J., Sankaranarayanan S. K. R. S., Effect of concentration on the energetics and dynamics of Li ion transport in anatase and amorphous TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 15661–15673 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas M. G. S. R., Bruce P. G., Goodenough J. B., Lithium mobility in the layered oxide Li1−xCoO2. Solid State Ion. 17, 13–19 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou C., Zhang Y., Li Y., Liu J., Construction of high-capacitance 3D CoO@polypyrrole nanowire array electrode for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitor. Nano Lett. 13, 2078–2085 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rakhi R. B., Chen W., Cha D., Alshareef H. N., Substrate dependent self-organization of mesoporous cobalt oxide nanowires with remarkable pseudocapacitance. Nano Lett. 12, 2559–2567 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zang X., Shen C., Kao E., Warren R., Zhang R., Teh K. S., Zhong J., Wei M., Li B., Chu Y., Sanghadasa M., Schwartzberg A., Lin L., Titanium disulfide coated carbon nanotube hybrid electrodes enable high energy density symmetric pseudocapacitors. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704754 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y., Lin Z., Zhong X., Huang X., Weiss N. O., Huang Y., Duan X.. Holey graphene frameworks for highly efficient capacitive energy storage. Nat. Commun. 5, 4554 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng C., Ling T., Ma T.-Y., Wang H., Hu Z., Zhou Y., Mao J., Du X.-W., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.-Z., Atomically and electronically coupled Pt and CoO hybrid nanocatalysts for enhanced electrocatalytic performance. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604607 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ling T., Yan D.-Y., Jiao Y., Wang H., Zheng Y., Zheng X., Mao J., Du X.-W., Hu Z., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.-Z., Engineering surface atomic structure of single-crystal cobalt (II) oxide nanorods for superior electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 7, 12876 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ling T., Yan D.-Y., Wang H., Jiao Y., Hu Z., Zheng Y., Zheng L., Mao J., Liu H., Du X.-W., Jaroniec M., Qiao S.-Z., Activating cobalt(II) oxide nanorods for efficient electrocatalysis by strain engineering. Nat. Commun. 8, 1509 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H., Ling T., Du X.-W., Gas-phase cation exchange toward porous single-crystal CoO nanorods for catalytic hydrogen production. Chem. Mater. 27, 352–357 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/10/eaau6261/DC1

Fig. S1. Schematic diagram of the cation exchange methodology for the synthesis of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S2. TEM characterizations of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S3. X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S4. SEM images of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S5. Composition analysis of a single Zn0.04Co0.96O NR.

Fig. S6. HAADF-STEM characterization of the as-exchanged ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S7. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy O 1s spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S8. Schematic illustration of the spatial distribution of O vacancies in a single ZnxCo1−xO NR.

Fig. S9. Analysis of lattice expansion of the surface region of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S10. Characterization of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated directly on CFP.

Fig. S11. XRD spectrum of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated on CFP.

Fig. S12. CV curves of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S13. Atom arrangements on low index planes of CoO.

Fig. S14. CV curves of ZnxCo1−xO NRs collected at scan rates from 5 to 1000 mV s−1.

Fig. S15. XPS spectra of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs before and after the cycling test.

Fig. S16. Structural characterizations of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs after the cycling test.

Fig. S17. Deconvolution of diffusion-controlled and capacitive-like capacitance in ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S18. O-K edge x-ray absorption near-edge structure spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs before and processed at −0.2 VAg/AgCl.

Fig. S19. Analysis of Co-L2,3 edge XAS spectra of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S20. Top-view and side-view illustration of O vacancy diffusion path through different surface facets.

Fig. S21. TEM image of an individual ZnxCo1−xO NR.

Fig. S22. Length distribution of ZnxCo1−xO NRs fabricated directly on CFP.

Fig. S23. Diffusion rate calculations for ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S24. M-S plots for ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S25. Electrochemical performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs as compared with P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Fig. S26. CV curve of carbon fiber paper.

Fig. S27. Simulation models of bulk CoO and Zn-doped CoO.

Table S1. Average O vacancy concentrations of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Table S2. Elemental analysis of Zn0.04Co0.96O NRs before and after the cycling test.

Table S3. Comparative summary of the performance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs in symmetric supercapacitor with the present symmetric supercapacitor and asymmetric supercapacitors.

Note S1. Analysis of the distribution of O vacancy on ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S2. Estimation of the theoretical capacitance of P-ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S3. Estimation of the theoretical capacitance of ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Note S4. Analysis of the oxygen intercalation mechanism in ZnxCo1−xO NRs.

Supplementary Methods