Abstract

Introduction:

Telemedicine describes a healthcare service where physicians communicate with patients remotely using telecommunication technologies. Telemedicine is being used to provide pre-/postoperative surgical consultation and monitoring as well as surgical education.

Aim:

Our purpose was to investigate the broad range of telemedicine technologies used in surgical care.

Material and methods:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Science Direct were searched for available literature from inception to March 30, 2018 with no language restrictions. The search terms included: cell phones, telemedicine, telecommunications, video, online, videoconferencing, remote consultation, surgery, preoperative, perioperative, postoperative, and surgical procedures. Studies were included if they used telemedicine in surgery for pre-, peri-, or post-surgery periods, and if they compared traditional surgical care with surgical telemedicine. We excluded case series, case reports, and conference abstracts from our review.

Results:

A total of 24 studies were included in our review. The study found that the use of telemedicine in preoperative assessment and diagnosis, evaluation after surgery and follow-up visits to be beneficial. Patients reported benefits to using telemedicine such as avoiding unnecessary trips to hospitals, saving time and reducing the number of working days missed.

Conclusion:

Telemedicine in surgical care can provide benefits to both patients and clinicians.

Keywords: Telemedicine, surgical procedure, satisfaction, monitoring

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1970s, the term ‘telemedicine’ has been used to describe a healthcare service where physicians can communicate with patients remotely using telecommunication technologies (1, 2). The roots of this evolving technology began in the early 20th century, when Willem Einthoven, a Dutch physiologist, established the first electrocardiograph in his laboratory in Leiden. Einthoven recorded the electrical cardiac signals of patients in a hospital 1½ km away by using a string galvanometer and telephone wires. Today, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines telemedicine as “the use of electronic information and communications technologies to provide and support health care when distance separates participants” (3).

In surgical care, telemedicine technologies have been used to provide pre/postoperative surgical consultations and monitoring, as well as surgical teleconferencing and education across borders (4-8). In 1998, Robie et al. found that telemedicine provided an accurate diagnosis for neonatal surgical consultations (9). Bullard et al. reported that mobile-phone images of CT scans appeared to be sufficient for neurosurgeons to make decision about their patients and reduced the need to transfer patients from referring hospitals by 30–50% (10). Another study found that using telemedicine for postoperative follow-up after cleft lip/cleft palate repair saved significant travel time and distance and allowed access to specialty services within a larger radius than would be possible for a clinical appointment (11). Furthermore, Urquhart et al. reported that telemedicine for routine postoperative follow-up after parathyroidectomy was safe and effective (12).

Although several studies have investigated specific modes of technology for telemedicine or the use of telemedicine within a particular surgical subspecialty, none have examined the use telemedicine in surgical care from a broad perspective. The purpose of this systematic review is to provide an overview of telemedicine use in surgical care.

2. METHODS

Publication search

A detailed search protocol was designed. The analysis and eligibility criteria were stated and documented according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (13). A systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Science Direct from the inception of the database up to March 2018. Keywords and medical subject headings relating to the condition and treatment were identified prior to initiating the search. Search terms included: cell phones, telemedicine, telecommunications, video, online, videoconferencing, remote consultation, surgery, preoperative, perioperative, postoperative, surgical procedures, operative, and monitor. All relevant article references were also manually searched to identify other related studies.

Eligibility

We systematically reviewed published studies according to originality, interventions, comparators, and study design. All the included articles addressed telemedicine use and surgery for pre-, peri-, or post-surgery periods. All types of surgery and comparative and non-comparative studies, such as randomized controlled trials and observational studies were included. We excluded reviews, case series, case reports, and conference abstracts. We also excluded robotic surgery studies.

Data extraction

Two authors (AA and SA) independently reviewed the abstracts for inclusion or exclusion. For each study, they independently extracted: year; setting; study design; population; and type of surgery. The authors (AA and SA) also recorded the type of telemedicine technology used, results, and limitations for each study.

3. RESULTS

Included studies

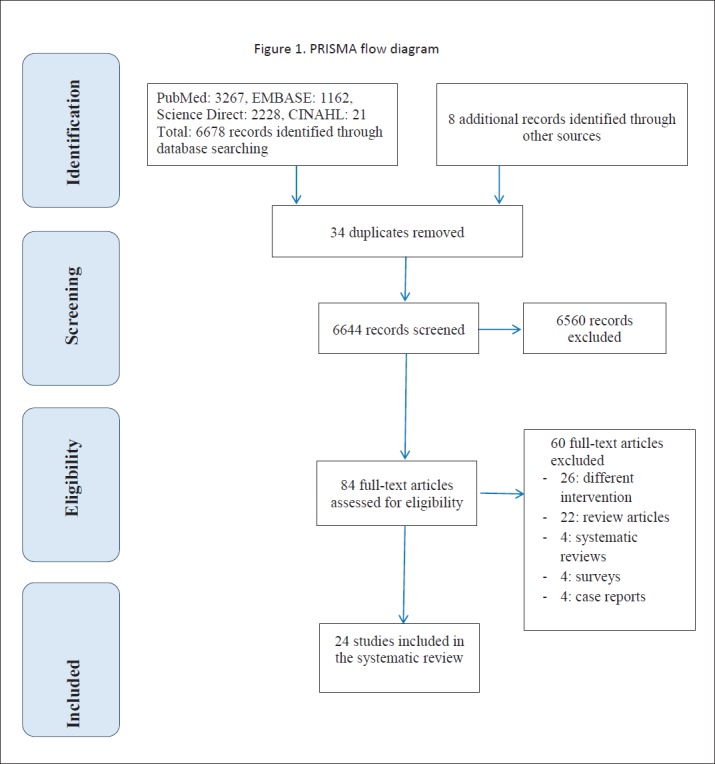

The primary search identified 6678 studies from the online databases and hand searching identified a further eight (Figure 1). After title screening, 84 articles were retrieved for full-text assessment. From those, 24 articles were included in our systematic review. Sixty articles were excluded for the following reasons: different intervention or outcome; review of the use of telemedicine; the advantage of installing telemedicine in healthcare; systematic review; case reports of patients that included type of telemedicine used; and surveys of patients or healthcare providers on the use of telemedicine in their institutions.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Of the included studies, three were randomized controlled trials, three were pilot studies, four were retrospective studies using data retrieved from medical records, and the remainder were prospective observational studies. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included articles in the study analysis.

| No. | First author, year | Study design/setting | Type of surgery included | Intervention | Comparison | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bednarski BK (16), 2018 | Prospective trial was conducted at a single academic institution | Ileostomy | Videoconferencing for postoperative assessment of ileostomy output patients post-discharge assessment using iPad 2 tablets and FaceTime | Usual care | Technology and telemedicine enabled greater connectivity between patients and their providers |

| 2 | Demartines N (17), 2000 | Prospective cohort study in which two hospitals, 120 miles apart, were connected via integrated services digital network (ISDN) tele-conferencing units | Digestive or endocrine surgery | Tele-transmission (tele-diagnosis) for judgment of organ structure and function pre-endocrine or gastric surgery |

Direct vision (direct diagnosis) |

Telemedicine increased and simplified the exchange and diffusion of medical knowledge, education, and information |

| 3 | Willard A (18), 2018 | Prospective cohort study design | Different pediatric surgeries | Video was used to visualize outpatient infants for follow-up post-surgery evaluation of wounds and medical equipment, such as nasogastric and gastrostomy tubes |

Usual care | Helped the team diagnose infection and evaluate patients’ sleep environment and follow-up readings on medical equipment |

| 4 | Martínez-Ramos C (19), 2009 | Pilot study | Ambulatory surgery | Using GPRS mobile-phone-based telemedicine system for the assessment of postoperative surgical wounds | Usual care | Improved home postoperative follow-up after ambulatory surgery |

| 5 | Robaldo A (20), 2010 | Prospective study | Carotid endarterectomy procedures | Discharge with mobile-phone monitoring ‘electronic BP’ and web-based videoconferencing, monitoring the patients every 4 h for 2 days |

Inpatient monitoring | Telemedicine appeared feasible and useful in carotid endarterectomy and may have other applications in vascular surgery care. |

| 6 | Wirthlin DJ (27), 1998 | Prospective study | Vascular surgery | Digital images to assess patients’ wounds | Bedside examination | Feasible on the basis of high concordance between remote and on-site surgeons regarding wound evaluation and management |

| 7 | Urquhart AC (12), 2011 | Prospective non-controlled study at a tertiary medical center of a cohort of 39 patients | Parathyroidectomy | Postoperative telehealth service using tablet computers to replace clinic visits | On-site examination | Telemedicine has the potential to greatly expand and improve cost-effective, high-quality care |

| 8 | Lee S (15), 2003 | Prospective cohort study | General surgery | Evaluation of patients via low-bandwidth telemedicine. Pre-screening was performed with digital image capture of pertinent physical findings or radiographs | On-site preoperative diagnosis | Internet-based surgical pre-screening was inexpensive and effective. The agreement of remote and on-site preoperative diagnosis was 100% |

| 9 | Hands L (16), 2004 | Prospective cohort study | Vascular surgery | Telemedicine clinic appointment to enable diagnosis and management decisions for patients referred to vascular surgery |

Conventional hospital outpatient appointment | Videoconference provided an important means of transmitting additional information. It also allowed patient and consultant to be introduced and possible alternatives for management to be discussed |

| 10 | Sudan R (17), 2011 | Prospective study | Bariatric surgery | Pre- and postoperative management were linked by teleconferencing and a computerized patient record system to evaluate and educate remote patients | Usual care | The preoperative evaluation process was considered adequate |

| 11 | Robie DK (9), 1998 | Prospective study | Pediatric surgery | Teleconsultation using desktop-computer-based system for preoperative diagnosis | Usual care | In all cases, the diagnosis was accurate, and appropriate plans for further diagnostic studies and treatment recommendations were made |

| 12 | Segura-Sampedro JJ (28), 2017 | Prospective pilot study | Appendectomy | Telemedicine-based evaluation (images of the surgical wounds of cases obtained via their own mobile devices) | Face-to-face consultation | Feasibility of telemedicine for the follow-up of wounds after emergency surgery |

| 13 | Scerri G (18), 1999 | Prospective study | Plastic surgery | Using digital camera to obtain specialist opinions in plastic surgery | Usual care | Telemedicine system was helpful in the management of plastic surgery and telemedicine images were reliable for diagnostic purposes |

| 14 | Wood EW (19), 2016 | Retrospective study | Maxillofacial surgery | Telemedicine consultations to provide accurate diagnosis and treatment plans for patients undergoing surgical treatment with anesthesia | Usual care | Telemedicine provided more timely access from primary care to specialist services, improved communication between providers, healthcare provider education, and increased cost effectiveness |

| 15 | Wallace D (20), 2008 | Retrospective study that was continued prospectively. | Acute plastic surgical trauma and burns | Management of patient with telemedicine to assess injuries | Usual care | Telemedicine systems proved useful in reducing unnecessary transfers in neurosurgical emergencies, and reduced mortality, complications, and costs in intensive care |

| 16 | Postuma R (21), 2005 | Retrospective study | Pediatric surgery | Telephone-based videoconferencing for plastic surgery consultations | In-person contacts in pediatric surgery ambulatory-care patients | Telehealth assessments took longer than in-person visits, but over time and with familiarity, the duration of telehealth and in-person sessions became the same. |

| 17 | Ellison LM (29), 2004 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Laparoscopic or percutaneous urologic procedures | Web-based videoconferencing system used for postoperative assessment ‘tele-rounding’ | Standard care | Tele-rounding was associated with greater patient satisfaction with postoperative care |

| 18 | Schlachta CM (22), 2009 | Prospective study | Laparoscopic colon surgery | Six tele-mentored group colon resections | 20 open colon resections | Mentored cases took longer but resulted in a shorter hospital stay. Wound complication occurred in one tele-monitored patient, with six in the comparator group. |

| 19 | Rao R (30), 2012 | Retrospective review | Breast surgery | Text messaging between patient and surgeon regarding surgical drain output | Usual care | Text messaging protocol reduced number of clinic visits (2.82 vs 3.65 in first 30 days, (p=0.0004), and decreased overall days of drain requirement (9.67 vs 12.45, p=0.013. |

| 20 | McGillicuddy JW (32), 2013 | Randomized control trial | Transplant surgery | Smartphone-based (Droid X, Motorola) medication adherence and blood pressure self- management system using a wireless Bluetooth blood pressure monitor (FORA D15b, Fora Care Inc) and a wireless GSM electronic medication tray (Med Minder, Maya, Inc,) in renal transplant recipients to improve long-term graft outcomes and better management of comorbidity | Standard care | Patients in the smartphone group had better medication adherence (p<0.05) and lower systolic blood pressure p=0.009 at 3 months compared with standard care patients; physicians made more medication adjustments in the smartphone group; patients using the smartphone system reported high satisfaction and ease of use with the system. |

| 21 | Sharareh B (33), 2014 | Non-randomized prospective study | Orthopedic surgery | Online video-conferencing via Skype used for routine postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty | In-person clinical visits | Telemedicine allowed effective communication and reduced the need to call the clinic for medical reasons |

| 22 | Canon S (31), 2014 | Retrospective study | Pediatric urology surgery | Online video-conferencing (unspecified commercial platform) from remote clinic site for routine postoperative follow-up after hypospadias repair, epispadias repair, circumcision revision, correction of buried penis, orchiopexy, orchiectomy, hernia repair, or hydrocelectomy | In-person follow-up | Postoperative assessment was considered approximately equivalent between the two groups as the number of follow-up appointments was similar and no additional on-site visits were needed post-telemedicine |

| 23 | Viers BR (34), 2015 | Randomized controlled trial | Urological surgery | Online video-conferencing via internally designed interface using video software and SBR Health software for routine follow-up after radical prostatectomy | In-person visit | Equivalent clinic efficiency between videoconference and in-person visits; high patient and provider satisfaction in the videoconference group; no acute urologic issues at 3 months follow-up; significant travel time and distance saved in videoconference group. |

| 24 | Sathiyakumar V (36), 2015 | Prospective randomized control trial (pilot study) | Orthopedic trauma | Telemedicine follow-up appointments via Skype | In-person follow-up visit | No difference in satisfaction. Patients were accepting of Skype follow-up and saved significant travel time and distance. |

Protocol for included studies

The types of telemedicine technology used in the studies were mainly teleconferencing, mobile phone and tablet applications (for example, Skype), digital images, and text messaging.

There were only three types of telemedicine protocols reported in the included studies. The first was for preoperative assessment, diagnostic purposes, or for consultation with another surgical department (9, 14-22). The second involved using telemedicine for postoperative wound assessment, from either a photograph of the surgical wound, via a health-monitoring machine, or an SMS from patients if they had an unusual symptom (23-31). The third used tele-monitoring in place of conventional clinics for follow-up (12, 32-35). Almost all of the studies included direct contact from patient to healthcare provider, which meant that, to be included in the studies, patients had to have Internet access. Some studies provided patients with smartphones or tablets so they could take part in the study. Only one study, by Demartines et al. (14), involved communication between two hospitals, which was part of the diagnostic process for patients undergoing digestive or endocrine surgery.

Clinical outcome

Studies that reported telemedicine for preoperative or diagnostic processes, such as Lee, et al., reported 100% agreement between the telemedicine technology and the on-site preoperative diagnostic results (15). Hands, et al. referred patients to the vascular surgery clinic via telemedicine and found the introduction of alternative management plans to be beneficial for consultants and patients (16). Demartines et al. discussed the accuracy of judging organ structure and function before digestive or endocrine surgery (14). Three studies found that preoperative diagnosis via telemedicine was as accurate as interventions carried out in usual conventional clinics (9, 17, 19). Wallace et al. used telemedicine to allow different surgical teams to evaluate patients’ injuries before they went into the operating room. The studies found that technology reduced unnecessary transfers to the neurosurgical department and also reduced complications during surgery (18, 20). Postuma and Loewen found that patients could use videoconferencing from their home desktop computer for plastic surgery consultations, saving them a trip to the hospital (21).

Four studies involved postoperative wound assessment via either photographs or teleconferencing. The authors found that a mobile-phone-assisted system improved postoperative follow-up and decreased the need for patients to attend ambulatory care for routine wound checks (25, 27, 28, 33, 36, 37). The third type of intervention was telemedicine for usual follow-up. Four studies used teleconferencing for usual postoperative care assessment and found that the technology enabled strong connectivity between patients and the healthcare provider (23, 31, 34, 35). Two studies described the use of videoconferencing via a mobile phone for remote patient monitoring using an electronic blood pressure monitoring device or for monitoring surgical drains and found that it was very beneficial for both parties (26, 30). One study described the use of telemedicine to see infants for follow-up to check on their sleep environment, readings on medical equipment, and for early detection of infection (24). Finally, McGillicuddy et al. reported that using smart phones led to improved long-term graft outcomes and better management for comorbidities compared with standard surgical care. The study found that telemedicine was associated with better medication adherence, lower systolic blood pressure and faster medication adjustment (32).

Patients’ satisfaction and money saved

One study, by Ellison et al. investigated patients who had undergone urological procedures; patients had, as the main outcome, patient satisfaction with the ‘tele-visit’ compared with usual care. More than 95% of patients in the tele-visit arm thought their care was good and considered that this should be the future for patient care (29). Nine other studies reported patients’ satisfaction with telemedicine (12, 17, 24, 25, 27, 29, 32-34). All studies reported high satisfaction using telemedicine, with scores ranging from 4.5 to 5 out of 5. Two studies that described patient satisfaction included reference to money saved (12, 19). Most of the patients’ comments were about avoiding unnecessary trips to hospitals, saving time and reducing the number of working days missed (24, 25).

4. DISCUSSION

Telemedicine technology is becoming an essential tool in healthcare delivery (2, 3, 38-43). This systematic review focused on the use of telemedicine in surgical care. We included studies comparing on-site consultations with telemedicine to enable us to draw practical conclusions about the use of this technology. Our study found that telemedicine was a useful technology to be used in surgical care according to all of the studies included in our review. The majority of studies reported the use of telemedicine between patients and healthcare providers and only one study compared telemedicine use between two hospitals.

The studies included in the review demonstrated the use of telemedicine in preoperative assessment and diagnosis, evaluation after surgery and follow-up visits to be beneficial. For postoperative evaluation and follow-up, five studies found videoconferencing feasible and useful. Digital images were suitable for the assessment of surgical wounds. According to Martínez-Ramos et al. telemedicine helped physicians assess local complications and avoid unnecessary hospital visits (25). Regarding preoperative diagnosis, telemedicine via internet-enabled computers was beneficial in two studies (9, 16). As for postoperative care, videoconferencing and digital cameras provided an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan.

One general limitation to the implementation of telemedicine technology has been noted. The development of this technology is not yet accessible to all hospitals for several reasons. First, the direct cost savings of telemedicine are still not significant for the healthcare system (36). Among the 24 studies reviewed, one reported that the cost of purchasing software and digital cameras to link desktop computers and transmitting live video in neonatal surgical consultations was between 5000–15,000 U.S. dollars (9). According to Wallace et al., there was no evidence of cost savings with telemedicine (20). Furthermore, healthcare providers need to be educated and trained on the use of telemedicine to apply it effectively. Our study shows telemedicine to have more advantages over traditional surgical care. Therefore, we suggest that healthcare providers implement telemedicine technologies in hospitals to support healthcare providers to deliver more efficient care. In terms of further research, we recommend conducting a randomized controlled trial or group trial because they provide more robust evidence than observational studies. As most of the studies included in our review used older and current technologies, up-to-date studies, looking at the new generation of technologies that will have an impact on how surgical care is practiced.

Implications for practice

This systematic review reports on the broad range of telemedicine technology use in surgical care. Telemedicine has potential benefits for surgical care in terms of providing improved efficiency and quality of care. It can improve healthcare access for a much larger patient population and decrease hospital readmissions. However, several challenges are associated with the development of telemedicine for surgeons. First, telemedicine requires different clinical skills, so surgeons should be educated on how to use telemedicine effectively. Moreover, surgeons must take into account patient privacy, which is a significant concern for the implementation of telemedicine. One of the current solutions is to use advanced encryption security protocols and standard, which can protect the privacy and confidentiality of patient information (15). Regardless of the challenges, telemedicine may result in fundamental changes in surgical practice.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study finds that telemedicine in surgical care can provide benefits to both patients and healthcare providers. Telemedicine can improve patient access to the healthcare system and provide significant time savings to both patients and healthcare providers. In addition, telemedicine can play an important role in improving care through the collaboration of surgical teams located at different sites. It is important to note that additional efforts are needed to overcome the barriers to implementing telemedicine technology in surgical care.

Author’s contribution:

All authors were included in all phases of preparation this article. Final proof reading was made by the first author.

Conflict of interest:

none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dasgupta P, Challacombe B. Robotics in urology. BJU International. 2004;93(3):247–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Challacombe B, Dasgupta P. Telemedicine - the future of surgery. The Journal of Surgery. 2003;1(1):15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field MJ. National Academies Press; 1996. Telemedicine: A guide to assessing telecommunications for health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB. Telemedicine using smartphones for oral and maxillofacial surgery consultation, communication, and treatment planning. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;67(11):2505–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosman AA, Fischer CA, Agha Z, Sigler A, Chao JJ, Dobke MK. Telemedicine and surgical education across borders: a case report. Journal of surgical education. 2009;66(2):102–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numanoglu A. Using telemedicine to teach paediatric surgery in resource - limited countries. Pediatric surgery international. 2017;33(4):471–474. doi: 10.1007/s00383-016-4051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latifi R, Mora F, Bekteshi F, Rivera R. Preoperative telemedicine evaluation of surgical mission patients: should we use it routinely. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2014;99(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stypulkowski K, Uppaluri S, Waisbren S. Telemedicine for Postoperative Visits at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center. Minnesota medicine. 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robie DK, Naulty CM, Parry RL, Motta C, Darling B, Micheals M, et al. Early experience using telemedicine for neonatal surgical consultations. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1998;33(7):1172–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullard TB, Rosenberg MS, Ladde J, Razack N, Villalobos HJ, Papa L. Digital images taken with a mobile phone can assist in the triage of neurosurgical patients to a level 1 trauma centre. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2013;19(2):80–83. doi: 10.1177/1357633x13476228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa MA, Yao CA, Gillenwater TJ, Taghva GH, Abrishami S, Green TA, et al. Telemedicine in cleft care: reliability and predictability in regional and international practice settings. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2015;26(4):1116–1120. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urquhart AC, Antoniotti NM, Berg RL. Telemedicine - An efficient and cost-effective approach in parathyroid surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2011;121(7):1422–1425. doi: 10.1002/lary.21812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demartines N, Otto U, Mutter D, Labler L, von Weymarn A, Vix M, et al. An evaluation of telemedicine in surgery: telediagnosis compared with direct diagnosis. Archives of Surgery. 2000;135(7):849–853. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Broderick TJ, Haynes J, Bagwell C, Doarn CR, Merrell RC. The role of low-bandwidth telemedicine in surgical prescreening. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2003;38(9):1281–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hands L, Jones R, Clarke M, Mahaffey W, Bangs I. The use of telemedicine in the management of vascular surgical referrals. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2004;10(1,suppl):38–40. doi: 10.1258/1357633042614212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sudan R, Salter M, Lynch T, Jacobs DO. Bariatric surgery using a network and teleconferencing to serve remote patients in the Veterans Administration Health Care System: feasibility and results. The American Journal of Surgery. 2011;202(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scerri G, Vassallo D. Initial plastic surgery experience with the first telemedicine links for the British Forces. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1999;52(4):294–298. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood EW, Strauss RA, Janus C, Carrico CK. Telemedicine consultations in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A follow-up study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2016;74(2):262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace D, Jones S, Milroy C, Pickford M. Telemedicine for acute plastic surgical trauma and burns. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2008;61(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postuma R, Loewen L. Telepediatric surgery: capturing clinical outcomes. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005;40(5):813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlachta CM, Kent SA, Lefebvre KL, McCune ML, Jayaraman S. A model for longitudinal mentoring and telementoring of laparoscopic colon surgery. Surgical endoscopy. 2009;23(7):1634–1638. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bednarski BK, Slack RS, Katz M, You YN, Papadopolous J, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al. Assessment of Ileostomy Output Using Telemedicine: A Feasibility Trial. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2018;61(1):77–83. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willard A, Brown E, Masten M, Brant M, Pouppirt N, Moran K, et al. Complex Surgical Infants Benefit from Postdischarge Telemedicine Visits. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2018;18(1):22–30. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Ramos C, Cerdán MT, López RS. Mobile phone-based telemedicine system for the home follow-up of patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(6):531–537. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robaldo A, Rousas N, Pane B, Spinella G, Palombo D. Telemedicine in vascular surgery: clinical experience in a single centre. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2010;16(7):374–377. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirthlin DJ, Buradagunta S, Edwards RA, Brewster DC, Cambria RP, Gertler JP, et al. Telemedicine in vascular surgery: feasibility of digital imaging for remote management of wounds. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1998;27(6):1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segura-Sampedro JJ, Rivero-Belenchón I, Pino-Díaz V, Sánchez MCR, Pareja-Ciuró F, Padillo-Ruiz J, et al. Feasibility and safety of surgical wound remote follow-up by smart phone in appendectomy: A pilot study. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2017;21:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellison LM, Pinto PA, Kim F, Ong AM, Patriciu A, Stoianovici D, et al. Telerounding and patient satisfaction after surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2004;199(4):523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao R, Shukla BM, Saint-Cyr M, Rao M, Teotia SS. Take two and text me in the morning: optimizing clinical time with a short messaging system. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012;130(1):44–49. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182547d63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canon S, Shera A, Patel A, Zamilpa I, Paddack J, Fisher PL, et al. A pilot study of telemedicine for post-operative urological care in children. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2014;20(8):427–430. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14555610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGillicuddy JW, Gregoski MJ, Weiland AK, Rock RA, Brunner-Jackson BM, Patel SK, et al. Mobile health medication adherence and blood pressure control in renal transplant recipients: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. JMIR research protocols. 2013;2(2) doi: 10.2196/resprot.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharareh B, Schwarzkopf R. Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):918–22. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, Tollefson MK, Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, et al. Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. European urology. 2015;68(4):729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sathiyakumar V, Apfeld JC, Obremskey WT, Thakore RV, Sethi MK. Prospective randomized controlled trial using telemedicine for follow-ups in an orthopedic trauma population: a pilot study. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2015;29(3):e139–e45. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandzuka M, Begic E, Boskovic D, Begic Z, Masic I. Mobile Clinical Decision Support System for Acid-base Balance Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendation. Acta Inform Med. 2017 Jun;25(2):121–125. doi: 10.5455/aim.2017.25.121-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masic I, Begic E. Mobile Clinical Decision Support Systems in our Hands - Great Potential but also a Concern. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;226:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mašić I, Hadžiahmetović Z, Toromanović S, Kudumović M. Telemedicina, virtuelna realnost, teleoperacije - hirurški aspekti. Med Arh. 2003;57(3, supl. 1):48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omerkić E, Mašić I, Hadžiahmetović Z. Telemedicina u urgentnoj medicini u BiH. Acta Inform Med. 2003;11(1-2):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadžiahmetović Z, Aginčić A, Mašić I. Telematika u urgentnoj medicini i hirurgiji. Med Arh. 2003;57(3, supl. 1):49. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mašić I, Bilalović N, Karčić S, Hadžiahmetović Z. Korijeni telemedicine u Bosni i Hercegovini u postdejtonskom periodu. Mater Sociomed. 2002;14(3-4):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masic I, Bilalovic N, Karcic S, Kudumovic M, Pasic E. Telemedicine and Telematics in B&H in the war and after Post war Times. European Journal of Medical Research. 2002;7(supl.1):47. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitten PS, Mair FS, Haycox A, May CR, Williams TL, Hellmich S. Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions. BMJ. 2002;324(7351):1434–1437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]