Abstract

Mechanotransduction refers to the processes whereby mechanical stimuli are converted into electrochemical signals that allow for the sensation of our surrounding environment through touch. Despite its fundamental role in our daily lives, the molecular and cellular mechanisms of mechanotransduction are not yet well-defined. Previous data suggest that keratinocytes may release factors that activate or modulate cutaneous sensory neuron terminals, including small molecules, lipids, peptides, proteins, and oligosaccharides. This study presents a first step towards identifying soluble mediators of keratinocyte-sensory neuron communication by evaluating the potential for top down mass spectrometry to identify proteoforms released during one minute of mechanical stimulation of mouse skin from naïve animals. Overall, this study identified 47 proteoforms in the secretome of mouse hind paw skin, of which 14 were differentially released during mechanical stimulation, and includes proteins with known and previously unknown relevance to mechanotransduction. Finally, this study outlines a bioinformatic workflow that merges output from two complementary analysis platforms for top down data and demonstrates the utility of this workflow for integrating quantitative and qualitative data.

Keywords: Mechanotransduction, keratinocytes, top down proteomics, label free quantitation, nociceptor, sensory neuron, touch, primary afferent, proteoforms

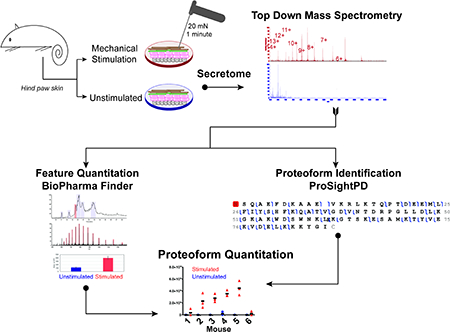

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Mechanotransduction refers to the processes whereby mechanical stimuli are converted into electrochemical signals that allow for the sensation of our surrounding environment through skin touch. The molecular and cellular mechanisms of mechanotransduction in skin play fundamental roles in our daily lives on a moment to moment basis: they allow us to perceive tactile stimuli from pleasant stroke to noxious insult, and they allow us to appropriately grip objects and accurately move our limbs. However, the mechanistic details of these vital processes are not yet well-defined. As our largest organ, the skin provides a vast receptive area for a plethora of diverse tactile inputs into the nervous system. Mechanical forces impact the skin and, via neural circuitry through the central nervous system, inform the brain about our physical environment, which in turn, guides our actions. Sensory neurons in the skin have long been assumed to be the major, if not the sole site for mechanotransduction. However, anatomically, sensory neurons are not the initial point of contact for mechanical stimuli to the skin. Rather, environmental stimuli first contact the outer epidermis. Ninety-five percent of the epidermis is comprised of keratinocytes, which are proximal to cutaneous sensory terminals, and synapse-like contacts with sensory neurons have been suggested 1–2. Although our understanding of the molecular events involved in mechanotransduction is incomplete, a landmark study in 2010 identified PIEZO1 and PIEZO2 as key ion channels that are directly mechanically sensitive and underlie the fast-activating and inactivating mechanical cation currents in many mammalian cell types 3. Subsequently, PIEZO2 was determined to be the key ion channel underlying mechanical currents and responsiveness in rapidly activating neurons that sense light touch in the skin 4.

Several studies have shown that non-neuronal Merkel cells, which comprise 3–6% of the glabrous or the hairy skin, also express PIEZO2 which is essential for Merkel cell mechanical sensitivity 5–7. Importantly, recent studies have demonstrated that Merkel cells are essential in modulating the response of slowly adapting type 1 Aβ-fiber sensory afferent terminals to sustained mechanical force and that mechanical force is detected via collaboration between Merkel cells and their innervating sensory afferent terminals 8–10. Furthermore, it has been suggested that Merkel discs utilize serotonin to convey tactile signals from Merkel cells to whisker afferent endings in the epidermis 11, thereby revealing a potential signaling mechanism between these two cell types. These findings introduced the concept that other non-neuronal cells in skin may also participate in modulating or tuning the response of cutaneous sensory neurons to tactile stimuli. Indeed, a recent study showed that selective optogenetic activation of keratinocytes is sufficient to drive action potentials in cutaneous sensory neurons 12. Conversely, optogenetic inhibition via stimulation of halorhodopsin in keratinocytes, which hyperpolarizes keratinocytes, is sufficient to dampen action potential firing in sensory neurons 12. Further, our recent study showed that keratinocytes play a vital role in the detection of innocuous and noxious touch 13. Mechanistically, keratinocytes release ATP upon innocuous and noxious touch, which in turn activates P2X4 receptors on sensory neurons, thereby causing action potential firing in the neurons leading to touch detection 13. Collectively, these data demonstrate that communication occurs between these keratinocytes and sensory neurons in response to tactile stimuli. However, inhibition of the ATP-P2X4 signaling cascade did not completely abolish mechanical behavioral responses in these animals 13. This is likely due to the expression of mechanically sensitive ion channels on sensory neurons 3, 14–15 and the possibility that keratinocytes may release other additional factors that activate or modulate cutaneous sensory nerve terminals in response to mechanical stimulation. Although keratinocytes are known to be capable of releasing neurotransmitters and neuropeptide signaling molecules such as ATP 16–17, calcitonin gene-related peptide β 18, acetylcholine 19, glutamate 20, epinephrine 21, neurotrophic growth factors 22, and cytokines 23, the signaling factors that are specifically released from intact skin in response to mechanical stimulation have not been comprehensively investigated.

Secreted or released factors involved in mechanotransduction may include soluble or microvesicle-bound small molecules, lipids, peptides, proteins, and oligosaccharides, among others. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the molecular signaling mechanisms involved in mechanotransduction will require identification, characterization, and quantitation of each of these molecular species. Mass spectrometry (MS) is well-suited for analyzing each of these molecular classes and is therefore expected to play a central role in revealing released factors involved in mechanotransduction signaling. Here, we utilized a top down MS approach to characterize proteoforms, which are collectively defined by a protein’s amino acid sequence, including cleavage and splice variants, and post-translational modifications, to provide precise whole-protein level information 24–25. As a first step towards comprehensively defining the molecular basis of mechanotransduction, the focus of this study was to determine whether it is possible to identify proteoforms released during one minute of mechanical stimulation of skin taken from naïve mice, using a minimalistic sample preparation approach. Overall, by merging outputs from two complementary analysis platforms for top down data, BioPharma Finder and ProSightPD, this study demonstrates that top down MS can identify proteoforms differentially released during mechanical stimulation of the skin and reveals proteoforms previously not reported to be involved in mechanotransduction.

Material and Methods

Animals and mechanical stimulation of glabrous hind paw skin

An overview of the experimental workflow is shown in Figure 1. Adult male C57BL/6 mice at least 8 weeks of age (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used. Mice were provided with food and water ad libitum and were housed in a 14:10 hour light:dark cycle on Sani-Chips® and aspen wood chip bedding (P.J. Murphy Forest and Products, New Jersey) with Enviro-dri® nesting material (Shepherd Specialty Papers, Michigan). All animals were maintained with experimental protocols approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin and performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval #: 0383). Animals were briefly anesthetized via inhaled isoflurane and then sacrificed via cervical dislocation in accordance with approved institutional protocols. For each mouse (n=6), the glabrous skin of both hind paws was cleaned with 70% ethanol, dissected away from muscle and tendons, cut into three equal sized sections approximately 3 × 3 mm. Sampling was randomized across anatomical distributions. Specifically, two sections (toe, middle or heel area) from each paw were assigned to one experimental group and the third was assigned to the other group; the opposite was done with the sections from the second paw. For example, if the toe and middle sections were assigned to the first group and the heel to the second group for the first paw, the heel was assigned to the first group and the toe and middle sections to the second group for the second paw. This allowed for equal anatomical distributions where each stimulation group contained one section from the toe area, middle section and heel area from each mouse. Each hind paw section was immediately placed with the stratum corneum facing down into individual wells of a 96-well plate filled with 80 μl of physiological buffer containing (in mM): 123 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 0.7 MgSO4, 1.7 NaH2PO4, 5.5 glucose, 7.5 sucrose, 9.5 sodium gluconate, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.45 +/− 0.05) or calcium-only buffer (2.0 mM aqueous CaCl2, pH 7.45 +/− 0.05). The skin section was then immediately and repeatedly mechanically stimulated (at roughly 2 Hz) for 1 minute with a 20 mN von Frey filament (i.e. mechanically stimulated) or left in the solution for the same time without mechanical probing (i.e. unstimulated). Importantly, the 20 mN force applied is on the lower ascending slope for the amount of force typically applied in ex vivo skin nerve preparations where the maximal stimulation is 200–300 mN, forces for which action potentials are routinely recorded from the embedded sensory terminals 26–27. Therefore, this stimulation is unlikely to result in tissue damage that would induce cellular apoptosis. Subsequently, the solution was removed from each well and the samples were kept on ice until MS analyses were performed. For each mouse, three biological replicates (i.e. separate hind paw skin sections) were prepared for each condition (mechanically stimulated vs. unstimulated). From each biological replicate, 10 μl was removed and used for protein quantitation using the Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) per manufacturer’s instructions. The remaining sample volume was adjusted with physiological buffer such that total protein concentration among three technical replicates within a single experimental condition for a single mouse were equivalent. One mouse, totaling 6 samples (3 mechanically stimulated + 3 unstimulated), was prepared per day to minimize the time each sample was stored at 4°C prior to MS analysis.

Figure 1. Experimental workflow for collection and processing of glabrous hind paw skin mechanotransduction secretome for top down proteomic analysis.

The overall workflow including experimental design and data analysis strategy are presented. The glabrous hind paw skin was dissected from both hind paws of euthanized mice and cut into three equal sized pieces each. The skin was either rapidly mechanically stimulated with a 20 mN von Frey filament or left unstimulated for 1 minute in the buffer. The supernatant was removed after one minute and kept on ice until MS analysis. Total amount of protein within each group (mechanically stimulated and unstimulated) was quantified and standardized to lowest total protein concentration. Three replicate injections of each sample were analyzed using a Q Exactive MS, yielding 9 mechanically stimulated and unstimulated replicates per mouse. The resulting 54 RAW files were analyzed separately by two platforms (ProsightPD and BioPharma Finder) and data were subsequently manually integrated by matching retention time and mass to integrate quantitative data for features identified in BioPharma Finder with proteoforms identified by ProsightPD.

Trypan blue staining of whole skin

Trypan blue staining was performed to test for cellular apoptosis. Whole skin from the glabrous hind paw was dissected from 4 euthanized mice as described above. Sections were randomly assigned in equal anatomical distribution to the three different groups (unstimulated, stimulated with 20 mN von Frey Filament and positive control with 18 g needle stimulation) similar to the sampling procedure described above such that the different sections from the same paw did not always receive the same treatment. For 1 min each, skin sections were either unstimulated, stimulated with the 20 mN von Frey Filament or stimulated with the 18g needle at approximately 2 Hz in the physiological buffer. The needle stimulation was performed so that the needle punctured the skin to guarantee damage, thus serving as a positive control. Subsequently, the skin was placed in a 50:50 mixture of Trypan Blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO) and physiological buffer for 30 seconds. The skin was quickly rinsed by dipping in physiological buffer prior to imaging using a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope.

Top down mass spectrometry

Samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography MS/MS using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in line with a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All technical details are provided in Table S1. For each injection, 20 μl neat sample (14–71 ng/μl) was loaded using full-loop injection mode onto a trap column (PepSwift Monolithic Trap 200 μm ID x 5 mm, Monolithic PS-DVB (Thermo Fisher Scientific)), and washed with mobile phase A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water) for 5 min at 8 μl/min before elution onto a PLRP-S PicoChip column (75 μm ID, 10.5 cm, 5 μm, 1000Å (New Objective, Woburn, MA)). Proteins were separated using a linear gradient from 2.0% mobile phase B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water) to 60.0% B in 20 minutes at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Proteins were analyzed using a top down strategy with in-source CID set at 15 eV, scan range of 500 – 2000 m/z, and four microscans were acquired for each spectrum. MS1 spectra were acquired using a target setting of 1×106 ions, an accumulation time of 50 ms, and scanned at a resolution of 140,000 (at 200 m/z). Each MS1 scan was followed by HCD fragmentation of the two most abundant precursor ions with a charge state of +4 or greater and dynamic exclusion set to 20 s. MS2 spectra were acquired using a target setting of 1 ×106 ions, an accumulation time of 150 ms, scanned at a resolution of 70,000 (at 200 m/z), isolation window set to 5.0 m/z, and normalized collision energy set to 21. For the initial test comparison of the two sample buffer solutions, a single injection was performed for each sample. For the subsequent analyses of the physiological buffer, three replicate injections were performed. All MS data files are publicly available at MassIVE (MSV000082059; massive.ucsd.edu).

Data Analysis – Identification

Data were analyzed using ProSightPD 1.1 (Proteinaceous, Evanston, IL)) as a plug-in node within Proteome Discoverer 2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were searched against Mus musculus (mouse) proteoform database (created 7/2016; top down complex database warehouse from Proteinaceous, 36,596 proteins, 3,259,647 proteoforms) using a two-tier search workflow as described in detail in Table S1. Briefly, tier one consisted of an absolute mass search with 2.2 Da precursor mass tolerance and 10 ppm fragment mass tolerance. Tier two consisted of a biomarker search with 10 ppm no-enzyme precursor mass tolerance and 10 ppm fragment mass tolerance. Results were filtered to include peptide spectrum matches (PSM) that were assigned a search engine rank of 1, -Log E-value ≥ 4 and more than 4 fragment ions. All proteoforms reported were identified by at least 10 PSMs and observed in at least three mice within a single experimental condition either based on ProSightPD (proteoform identified) or BioPharma Finder (precursor mass detected; see below). To match components detected in BioPharma Finder with proteoforms identified by ProSightPD, features were required to match within 0.1 Da to a PSM assigned to specific proteoform by ProsightPD and within a 1 min window (± 30 sec) around the average retention time reported by ProsightPD. In some cases, proteoforms identified in ProsightPD could not be matched with certainty to specific features reported by BioPharma Finder and are annotated as ‘ambiguous’ in Table S2.

Data Analysis – Relative Quantitation

Data were analyzed with BioPharma Finder version 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). An intact protein workflow processing method was created for Sliding Window Deconvolution using the Xtract deconvolution algorithm. Chromatograms were scanned over full retention time range with charge state range of +4 to +40, sliding windows merge tolerance for components was 30 ppm, multiconsensus component merge tolerance was 10ppm, and the minimum number of detected charge states to produce a component were designated as 3. For each comparison set, the monoisotopic masses of components, their sum intensities for all charge states detected, charge state distribution, retention time range, and the number of raw files found to contain those with corresponding intensities were exported to Excel for further processing. The average intensity for each feature was calculated per hind paw section per mouse. Non-detected features were assigned a value of zero. Average intensity values were normalized by a scaling factor based on total protein quantity and the statistical significance between treatment groups and among mice was assessed by a paired two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison tests. A paired two-way ANOVA was chosen because multiple mechanically stimulated and unstimulated samples were obtained from the same animal. In this way, the stimulated and unstimulated sections for each mouse were compared as groups, treating the three sections in each group as independent measurements. Statistical analysis was only performed for features which could be matched to proteoforms identified by ProSightPD and which were identified in at least 3 mice. The stimulated to unstimulated ratio reported in Table 2 was calculated on a per-mouse basis taking the average normalized intensity of the groups of stimulated and unstimulated sections.

Table 2. Summary of proteoform quantitation results from BioPharma Finder.

For each proteoform, the mass (Theoretical MH+ in Da), protein symbol, number of mice and hind paw sections in which it was detected by BioPharma Finder for each condition, ratio of S/U (mechanically stimulated/ unstimulated) per mouse, and statistical significance between treatment groups are provided. U = unstimulated; S = mechanically stimulated. Statistical comparisons were made between treatment (unstimulated versus mechanically stimulated) and among mice via a paired two-way ANOVA followed by a Sidaks post hoc test. *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, n.s. denotes a non-significant result. Proteoforms are grouped by statistical significance, where top section = not significantly different among groups, middle = more abundant in mechanically stimulated samples, bottom = less abundant in the mechanically stimulated samples.

| # of Mice Observed In | # of Sections Observed In | Ratio (S/U) per Mouse | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Mass MH+ | Protein Symbol | U | S | U | S | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Significant Difference |

| Not statistically significant between groups | ||||||||||||

| 2791.43 | ALB | 5 | 6 | 17 | 17 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | ns |

| 7201.63 | ATOX1 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ns |

| 11081.56 | CSTB | 6 | 4 | 17 | 11 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | U | 0.3 | U | ns |

| 5534.92 | FAM25C | 2 | 6 | 8 | 14 | S | S | 1.4 | 1.3 | S | 0.5 | ns |

| 14972.73 | HBA | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.8 | ns |

| 15039.37 | HBA | 6 | 6 | 17 | 18 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | ns |

| 3736.06 | HBB-B1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | U | ND | 0.3 | S | ns |

| 8249.42 | HNRNPK | 4 | 5 | 13 | 13 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.3 | ND | 0.4 | ns |

| 9956.27 | S100A6 | 4 | 6 | 14 | 17 | S | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.6 | ns |

| 11544.93 | STFA3 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | U | ND | ND | ns |

| 4961.49 | TMSB4X | 5 | 6 | 16 | 18 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 9.1 | 1.1 | ns |

| More Abundant in Stimulated | ||||||||||||

| 8704.20 | APOA2 | 5 | 5 | 14 | 15 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 5.1 | ND | **** |

| 6821.69 | APOC1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 14 | S | S | S | 20.4 | S | S | **** |

| 9272.87 | FAM25C | 4 | 6 | 11 | 18 | S | 4.3 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 0.6 | * |

| 2604.29 | FLG | 0 | 6 | 0 | 12 | S | S | S | S | S | S | * |

| 8103.21 | HMGB1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 12 | S | S | S | S | S | S | *** |

| 10867.84 | HSPE1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 18 | 5.6 | 15.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 | S | 1.5 | ** |

| 11048.49 | S100A10 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 9 | S | S | S | S | S | S | ** |

| Less Abundant in Stimulated | ||||||||||||

| 8950.57 | CALM4 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 10 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | U | ** |

| 9363.77 | CALM4 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ** |

| 16668.42 | CALM4 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 17 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | ** |

| 9906.12 | DBI | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | * |

| 9922.10 | DBI | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | **** |

| 11785.07 | FKBP1A | 4 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | U | ND | ND | * |

| 12366.14 | MIF | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | ND | ND | U | 0.1 | ND | U | ** |

Results

The method used to mechanically stimulate the glabrous hind paw skin in this study is similar to the ex vivo glabrous skin-nerve preparations we routinely utilize for electrophysiological functional assessment of cutaneous terminals of primary afferent fibers 13, 26, 28. The isolated glabrous hind paw skin was mechanically stimulated with graded von Frey filaments. Modest force (20 mN) was used to avoid tissue damage and this force is in the lower half of the range we use for skin-nerve electrophysiological recordings (2–300 mN) 13, 29. Further, we routinely observe that when skin-nerve preparations are maintained ex vivo in physiological buffer, the nerve terminals retain their physiological viability and response properties for at least six hours. Here, trypan blue staining of whole skin was used as an estimate of cellular apoptosis. Trypan blue is routinely used as a stain to assess cell viability via a dye exclusion test; as such, viable cells should not take up the impermeable trypan blue dye. Upon visual inspection of the skin sections, no significant differences were found between the unstimulated and the 20 mN (2 Hz for 1min) mechanically stimulated group (Figure S1 A and B). However, the positive control (Figure S1C, 18g needle stimulation) showed significantly more blue staining than either the unstimulated sections or the sections stimulated with the 20 mN von Frey filament (Figure S1 A-C). Overall, our previous findings of viable skin-nerve preparations that utilize a range of mechanical forces,13, 26, 28 and the trypan blue staining results from the current study suggest that there is limited cell death using this approach. Altogether, these observations support the use of this method for studies aimed at identifying mechanically-released proteins. To minimize technical artifacts that may result from drying under vacuum, freezing, or extensive sample handling, we tested whether the analysis of neat samples would yield sufficient protein content to provide interpretable top down MS data and began MS analyses immediately after sample collection. Although the physiological buffer is expected to yield more biologically relevant data than the calcium buffer, it was initially unclear whether the physiological buffer components would adversely affect MS performance. Therefore, preliminary experiments compared mechanically stimulated and unstimulated samples from both buffer types. In these analyses, the physiological buffer did not appear to interfere with the identification of proteoforms as compared to the calcium-only buffer (data not shown). Moreover, most proteins identified as putatively unique to the mechanically stimulated condition as compared to the unstimulated samples for the calcium-only buffer (data not shown) were also observed in the mechanically stimulated condition for the physiological buffer. Therefore, all remaining analyses were conducted in the physiological buffer because it is a more biologically relevant matrix. Finally, we considered whether sample stability at 4ºC would present challenges. Although samples for a single mouse were collected simultaneously, MS data were acquired in series with ~60 min separating each injection. Importantly, we did not observe any significant trends that tracked with the order in which samples were analyzed that would indicate that samples run later in the queue were missing proteins or contained degraded proteoforms compared to those run earlier. Altogether, these observations support the utility of the approach for revealing putative differences related to the experimental condition as opposed to technical artifacts.

Overall, 47 proteoforms were identified by ProsightPD in the comparison of mechanically stimulated vs unstimulated groups (Table 1; Table S2, Figures S2-S3). The majority (90%) of proteins identified here are annotated as extracellular or extracellular exosome-related (UniProt). This finding supports the utility of this approach for identifying secreted proteins, although some likely contaminants are present (e.g. fragments of hemoglobin, albumin). Thirty proteoforms represent ≥99% coverage of the intact protein (Table 1), suggesting that proteolytic cleavage resulting from sample handling was minimal. For those proteoforms that represent cleavage products, most are consistent with known biology. For example, filaggrin plays a pivotal role in skin barrier function 30, and the cleavage products for filaggrin observed here in both unstimulated and mechanically stimulated samples are consistent with the extensive proteolytic degradation of filaggrin that occurs during epidermal terminal differentiation 30.

Table 1.

Proteoforms identified in the comparison of mechanically stimulated vs. unstimulated samples. For each proteoform, the UniProt accession number, protein symbol, proteoform mass (Theoretical MH+ (Da)), number of peptide spectrum matches (PSM) observed across all 6 mice (+ mechanically stimulated; - unstimulated) are provided. The “sequence length” was calculated based on the fully processed form (i.e. after removal of signal peptide or initiator methionine). Posttranslational modifications and/or other notable features regarding the proteoform sequence observed are noted. For proteoforms that differ from the predicted full-length sequence by more than N- or C- terminal processing, the amino acid residues contained in the proteoform, based on the pre-processing sequence, are also noted. Additional MS data supporting this information are provided in Table S2.

| UniProt | Protein Symbol | Mass (Da) | #PSM | Sequence Length | Modifications, Features, [Residues] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | |||||

| P07724 | ALB | 2791.43 | 72 | 98 | 4 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) [25–48] |

| P09813 | APOA2 | 8704.20 | 142 | 213 | 99 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) N-term(2-pyrrolidone-5-carboxylic acid) Truncated last C-terminal amino acid |

| P09813 | APOA2 | 8721.22 | 10 | 39 | 99 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) Truncated last C-terminal amino acid |

| P34928 | APOC1 | 6821.69 | 0 | 22 | 99 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) Truncated first two N-terminal amino acids |

| O08997 | ATOX1 | 7201.63 | 187 | 158 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) Disulfide (C11-C14) |

| P01887 | B2M | 11634.70 | 65 | 101 | 100 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) Disulfide (C25-C80) |

| P01887 | B2M | 11635.65 | 40 | 54 | 100 | N-terminally processed (signal peptide) Disulfide (C25-C80) K→E variant at K64 |

| P0DP26 | CALM1 | 16780.82 | 54 | 20 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation Acetylation at K94 |

| P0DP26 | CALM1 | 16780.86 | 112 | 45 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation Trimethylation at K115 |

| Q9JM83 | CALM4 | 8950.57 | 81 | 32 | 53 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation [2–80] |

| Q9JM83 | CALM4 | 9363.77 | 208 | 165 | 55 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation [2–84] |

| Q9JM83 | CALM4 | 16668.42 | 203 | 183 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| Q9D6P8 | CALML3 | 16602.79 | 75 | 38 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P62965 | CRABP1 | 15451.73 | 5 | 15 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| Q62426 | CSTB | 11081.56 | 8 | 29 | 100 | N-term acetylation |

| P31786 | DBI | 9906.12 | 451 | 468 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P31786 | DBI | 9922.03 | 12 | 0 | 98 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation Malonyl-Lysine (K54) Succinyl-Lysine (K60) |

| Q05816 | FABP5 | 15039.37 | 315 | 413 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| Q8CF02 | FAM25C | 5534.93 | 16 | 41 | 58 | [38–89] |

| Q8CF02 | FAM25C | 9272.87 | 150 | 281 | 100 | N-term acetylation |

| P26883 | FKBP1A | 11785.07 | 42 | 25 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| P11088 | FLG | 2448.19 | 4 | 27 | 8 | [47–74] |

| P11088 | FLG | 2604.29 | 9 | 37 | 8 | [46–74] |

| P01942 | HBA | 3344.67 | 20 | 64 | 22 | [2–33] |

| P01942 | HBA | 3880.08 | 8 | 27 | 25 | [107–142] |

| P01942 | HBA | 6674.58 | 10 | 7 | 43 | [82–142] |

| P01942 | HBA | 14972.74 | 388 | 414 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| P02088 | HBB-B1 | 3636.99 | 12 | 10 | 24 | [113–147] |

| P02088 | HBB-B1 | 3736.06 | 54 | 54 | 25 | [112–147] |

| P63158 | HMGB1 | 8103.21 | 0 | 11 | 33 | [90–161] (B-box domain) |

| P61979–1 | HNRNPK | 8249.42 | 33 | 41 | 19 | [381–457] |

| Q64433 | HSPE1 | 10867.84 | 36 | 110 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P34884 | MIF | 12366.14 | 60 | 30 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| P17742 | PPIA | 17829.82 | 10 | 5 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| P17742 | PPIA | 17871.83 | 18 | 6 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| Q9D0J8 | PTMS | 11335.12 | 57 | 12 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P32848 | PVALB | 11835.07 | 24 | 5 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| Q99P72–2 | RTN4 | 7409.27 | 29 | 15 | 5 | N-term acetylation [1–65] |

| P08207 | S100A10 | 11048.49 | 0 | 50 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) |

| P07091 | S100A4 | 11625.72 | 23 | 5 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P14069 | S100A6 | 9956.27 | 74 | 72 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P60897 | SEM1 | 8184.54 | 19 | 35 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| Q00897 | SERPINA1D | 4205.20 | 11 | 15 | 8 | [378–413] |

| P61957 | SUMO2 | 10514.21 | 26 | 18 | 97 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation Truncated last two C-terminal amino acids [2–93] |

| Q6ZWY8 | TMSB10 | 4934.53 | 16 | 2 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P20065–2 | TMSB4X | 4961.49 | 111 | 132 | 100 | N-terminally processed (Met) N-term acetylation |

| P62984 | UBA52 | 8560.62 | 114 | 81 | 100 | Fully processed [1–76], without 77–128 C-terminal 60S ribosomal protein L40 |

Details of the quantitative workflow are shown in Figure 2. The mechanically stimulated samples routinely yielded a higher total protein content (2–3 fold) compared to unstimulated samples; therefore, to avoid over-diluting the mechanically stimulated samples and to account for the fact that each mouse was processed separately, total protein content was normalized within a treatment group (mechanically stimulated or unstimulated) for each animal. To account for this during data analysis, the summed intensity for a proteoform was normalized by a scaling factor reflective of differences in total protein quantity. Overall, this strategy revealed 11 proteoforms that were not statistically significantly different between the treatment groups (Table 2) including those that are likely background contaminants (e.g. albumin, hemoglobin, copper transport protein ATOX1).

Figure 2. Experimental workflow for quantitative analysis of top down data.

Raw peak data were extracted in BioPharma Finder and processed to calculate the average summed intensity for each extracted feature per hind paw section. Differences in the amount of injected protein were used to normalize the summed intensities. Hind paw sections from the same mouse were treated as paired for statistical analysis. Plots for proteoforms of interest in Figures 3–4 were generated to visualize the normalized summed peak intensities, wherein the data points represent individual hind paw sections per mouse. The mean for sample groups (mechanically stimulated and unstimulated) are shown on a per mouse basis (horizontal bars) and across mice (listed at the top of each plot).

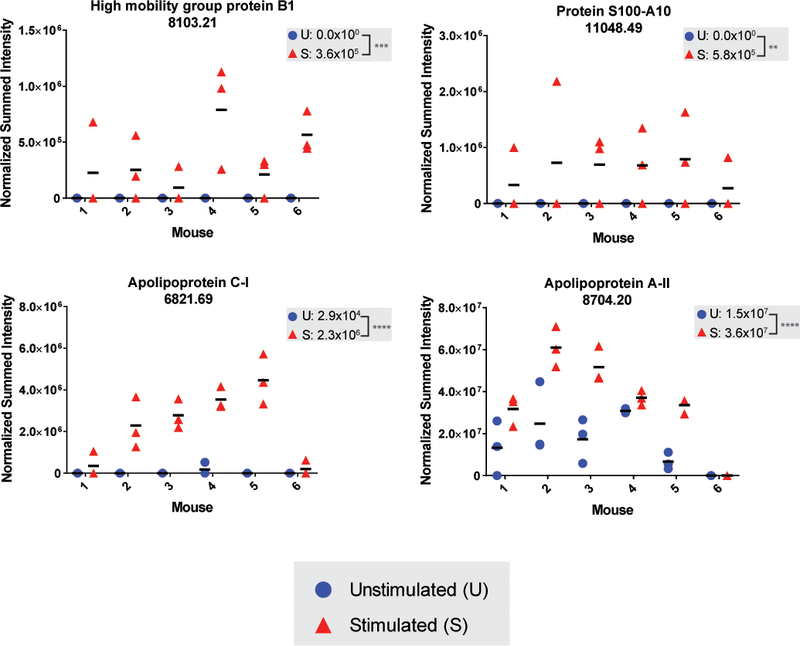

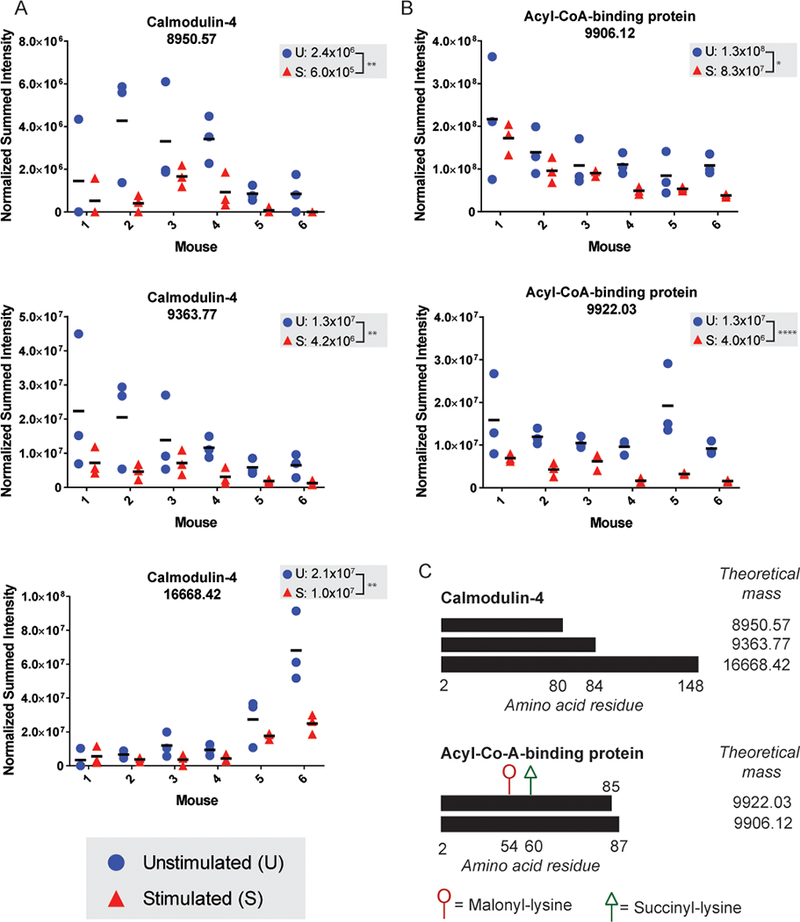

Seven proteoforms were either exclusively detected in the mechanically stimulated group or were significantly more abundant in the mechanically stimulated compared to the unstimulated group. These include proteoforms 8103.21 and 11048.49 from High mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) and Protein S100-A10 (S100A10), respectively, which were identified uniquely in the mechanically stimulated group by ProSightPD (Table 1). Quantitative analyses from BioPharma Finder were consistent with the identification results, where deconvoluted monoisotopic MS1 values were only detected in the mechanically stimulated group (Figure 3A-B). Results for proteoform 6821.69 from Apolipoprotein C-I (APOC1) were similarly consistent between the two platforms, as it was identified uniquely in the mechanically stimulated group by ProSightPD and quantitation in BioPharma Finder found low level detection only in unstimulated hind paw sections of a single mouse (Figure 3C). Proteoform 8704.2 from Apolipoprotein A-II (APOA2) was more abundant in the mechanically stimulated condition across the five mice in which it was detected by BioPharma Finder (Figure 3D), consistent with more PSMs identified in mechanically stimulated (n=213) than in unstimulated (n=142) samples by ProSightPD (Table 1). Finally, seven proteoforms were less abundant in the mechanically stimulated samples, including three proteoforms of Calmodulin-4 (CALM4; 8950.57, 9363.77, 16668.42; Figure 4A; Table 2) which represent the full length and cleaved forms (Figure 4C), respectively, and two proteoforms of Acyl-CoA-Binding protein (DBI; 9906.12, 9922.10; Table 2, Figure 4B), which represent unmodified full-length protein and modified truncated protein (Figure 4C), respectively.

Figure 3. Examples of proteoforms that are more abundant in the mechanically stimulated samples.

Plots display the normalized summed peak intensities for each proteoform wherein the data points represent individual hind paw sections per mouse for (A) HMGB1, (B) S100A10, (C) APOC1, and (D) APOA2. The means for sample groups (mechanically stimulated and unstimulated) are shown on a per mouse basis (horizontal bars) and across mice (listed at the top of each plot). Statistical significance is indicated and statistical comparisons are based on a paired two-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, n.s. denotes a non-significant result). Supporting MS data for each proteoform are provided in Figure S2.

Figure 4. Examples of proteoforms that are less abundant in the mechanically stimulated samples.

Plots display the normalized summed peak intensities for (A) CALM4 and (B) DBI wherein the data points represent individual hind paw sections per mouse. The means for sample groups (mechanically stimulated and unstimulated) are shown on a per mouse basis (horizontal bars) and across mice (listed at the top of each plot). Statistical significance is indicated and statistical comparisons are based on a paired two-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, n.s. denotes a non-significant result). (C) Visual representation of the observed proteoform sequences for Calmodulin-4 and Acetyl-CoA-Binding Protein shown next to the theoretical masses (in Da). Supporting MS data for each proteoform are provided in Figure S3.

Overall, these analyses suggest that even with limited protein content (280–1420 ng per MS injection) and short duration (1 min) of mechanical stimulation of the skin, top down MS can reveal proteoforms that are differentially released with mechanical stimulation. Although there are variations in the summed peak intensity for individual proteoforms among animals, which is consistent with the fact that samples among animals were not normalized to each other due to their collection and analysis on different days, the trends in the relationship between mechanically stimulated and unstimulated among animals are largely consistent for the proteoforms quantified here. Altogether, these analyses highlight the power of integrating data between two platforms (ProsightPD and BioPharma Finder), as BioPharma Finder provides relative quantitation based on extracted ion chromatograms from multiple charge states but not proteoform identity, and ProSightPD provides identity and the number of PSMs observed.

Discussion and Conclusions

Although significant progress has been made in identifying ion channels involved in mechanotransduction 27, 31–33, a detailed understanding of the full complement of molecules involved in signaling processes that occur between non-neuronal skin cells, such as keratinocytes and sensory neurons, is not yet established. Such information is important for advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that regulate baseline mechanosensory detection, as well as the mechanical sensitization that occurs with tissue injury or disease. Moreover, it is expected that precisely defining the molecules involved in cell-to-cell communication in the skin could lead to potentially novel topical analgesics or antipruritics. Keratinocytes have been shown to communicate with multiple subtypes of sensory neurons 12–13, 34. Different neuronal subtypes are thought to transmit different sensations; for example Aβ fibers generally transmit gentle touch, whereas C fibers generally transmit painful stimuli35. Therefore, mechanistically defining keratinocyte to sensory neuron signaling may reveal mechanisms underlying transmission of innocuous and noxious mechanical stimuli during both acute pain and chronic pain settings, and during acute or chronic itch conditions. To address this knowledge gap, we applied top down MS to quantify and characterize proteoforms released by cutaneous mechanical stimulation of mouse skin. MS is well-suited to the analysis of factors that are rapidly released during mechanotransduction as it can directly identify and quantify proteins with very low limits of detection without antibodies or a priori knowledge of the molecular composition.

Among the proteoforms identified as uniquely present or more abundant in the mechanically stimulated samples, HMGB1, APOA2, APOC1, and S100A10 are particularly interesting due to their known biological relevance to skin biology, including pain. HMGB1 can be released from keratinocytes, and the injection of complete HMGB1 protein into the hind paw of mice causes acute nociceptive behaviors in vivo 36–37. Although HMGB1 is known for its proinflammatory functions, it has also been shown to promote skin wound healing 38. Our MS analysis revealed that specifically the B-box domain of HMGB1 (residues 90–161), which contains the cytokine activity and toll-like receptor binding domain, was found in the mechanically stimulated condition. The B-box domain has been demonstrated to recapitulate the cytokine activity of full length HMGB1 where it can efficiently induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines from macrophages39–40. Additionally, the B-box domain of HMGB1 has been shown to induce marked derangements in gastrointestinal mucosal barrier function in mice 40–41, which further suggests a role for HMGB1 B-box domain in inducing functional alterations in epithelial cells. Another protein found in higher abundance in the stimulated group was S100A10. S100A10 is found in both the cytoplasm and periphery of basal and suprabasal keratinocytes 42. In normal epidermis it is localized to the nucleus and cytoplasm, however, in psoriatic tissue, its localization is increased in the plasma membrane 43. S100A10 also interacts with ion channels such as Nav1.8, which are involved in neuropathic pain and are expressed in keratinocytes and nociceptive sensory neurons 44–46. Therefore, it is possible that these ion channels can be modulated through the interaction with S100A10, which tethers them to the cell membranes. In summary, the crucial role of S100A10 in keratinocyte differentiation47 and its interactions at the plasma membrane are consistent with the increased release upon mechanical stimulation observed here. Finally, APOA2 and APOC1 were more abundant in the stimulated samples. Although APOC1 is perhaps better recognized as an important lipoprotein binding protein in circulating blood, APOC1 is also normally expressed in the skin 48. Importantly, mice that lack APOC1 exhibit cutaneous abnormalities such as dry scaly skin with hair loss, whereas mice that express human APOC1 exhibit dermatitis and atrophic sebaceous glands lacking sebum 49–51. These data suggest that APOC1 may have a crucial role in lipid homeostasis of the skin that is consistent with its role in binding and transporting lipids among various tissues 52. APOC1 has also been shown to be upregulated after mechanical massage of femoral adipose tissue53. This is consistent with our results where APOC1 abundance was increased in samples after mechanical stimulation. Two APOA2 proteoforms were identified, and while both were observed by more PSMs in the stimulated, only the proteoform with pyrrolidone carboxylic acid at the N-terminus reached a level of statistical significance in the quantitation. This modification can protect proteins from degradation by amniopeptidases, is commonly observed in secreted proteins, and has been reported on human APOA254. APOA2 is involved in mediating cholesterol efflux from cell membranes55 and reductions in plasma membrane cholesterol dampen mechanotransduction responses 56. Lipids such as cholesterol-enriched membrane domains have been suggested to play roles in the mechanotransduction process56. Therefore, APOA2 may play a role in mechanotransduction processes by modifying membrane cholesterol content. Additionally, APOA2 is expressed in basal cells in the epidermis and APOA2 has been linked to cell proliferation and differentiation57. Altogether, whereas, previously described functions of HMGB1, S100A10, APOC1 and APOA2 have suggested that they have important roles in epidermal physiology, our study is the first to directly link these proteins to mechanotransduction through their release upon mechanical stimulation of skin.

Our study also identified several proteoforms that were less abundant in the secretome after mechanical stimulation. This includes two proteoforms of Acyl-CoA-binding protein abbreviated as ACBP and also known as diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI). One proteoform of DBI is missing the last two C-terminal amino acids and contains both malonyl-lysine and succinyl-lysine modifications. While these modifications have recently been implicated as important regulators of metabolism, our knowledge regarding their biological significance is still in its infancy58–60. Malonyl-lysine and succinyllysine modifications induce dramatic structural changes on lysine residues due to their large size and they frequently occur together61. Our data are consistent with these previous observations, however, in the context of DBI proteoforms, the biological consequence of these modifications is yet unknown. Generally, DBI is a negative allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors that play a critical role in skin barrier homeostasis in keratinocytes 62–63. Skin tissue injury has been suggested to cause the depolarization of keratinocytes and prevent wound healing. In contrast, repolarizing keratinocytes via GABAA-like receptors could be crucial in promoting wound healing through the fusion of the lamellar body and cell membrane 62. Moreover, DBI has been shown to have anti-nociceptive effects in the central nervous system 64 and can be released through an unconventional secretion mechanism in yeast 65 where DBI is secreted despite its absence of a canonical signal peptide. It is possible that DBI is endogenously present in the extracellular space of the skin, such that in absence of stimulation, DBI normally inhibits diazepam from binding to GABAA receptors, akin to its action in the brain 66. Upon mechanical stimulation of the skin, DBI could be degraded or prevented from acting on GABA receptors and thereby, allow for the disinhibition of GABAA receptors.

Alternatively, DBI has also been shown to regulate lipid metabolism. DBI knockout animals have been shown to have a >50% decrease in non-esterified very long chain fatty acid skin content as compared to wild type mice, and show distinct skin and fur phenotypes that are characterized by greasy fur and coat color changes that develop into alopecia with age67. This suggests that DBI is important in incorporating very long chain acyl-CoA esters in complex lipids into the epidermis, and therefore may be necessary for normal skin barrier function. It is possible that its secretion is regulated by interactions with intracellular acyl-CoA-esters 68–69, thereby preventing secretion or alternatively interfering with their detection by this MS strategy.

Finally, three proteoforms of CALM4 were found to be less abundant in the stimulated samples. CALM4 is a calcium binding protein strongly expressed in subrabasal keratinocytes and plays a role in restoring epidermal calcium gradient during wound healing and barrier formation 70–71. Interestingly, the subcellular localization of CALM4 in keratinocytes is linked to intracellular calcium concentrations and during acute barrier disruption where intracellular calcium is increased, CALM4 localizes to the nucleus 71. Keratinocytes have been shown to respond to mechanical stimulation and allow calcium influx from the extracellular space72. Therefore, it is possible that upon mechanical stimulation of the skin, CALM4 is less available for secretion due to changes in intracellular calcium and its translocation to the nucleus. Additionally, intracellular calmodulin has also been shown to inhibit several ion channels upon binding, such as NMDA receptors, voltage gated sodium channels and calcium channels73–76. Several ion channels, such as Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channel family members (i.e. TRPC6 and TRPV1), have been shown to have a prominent overlap between phosphoinositides and calmodulin-binding sites77. It is possible that the mechanical stimulation of the skin alters the phosphoinositide composition in keratinocyte or sensory neuron cell membranes within the skin. This could lead to the release of the inhibitory calmodulin-ion channel interaction, allowing ion channel activation. Overall, while it is not yet clear why these proteoforms were detected in lower abundance in the stimulated samples, their known functional roles and interactions with other molecules largely support several possibilities, including the mechanically-induced release of enzymes that degrade these proteins, or the stimulation of a signaling cascade that leads to the sequestration or degradation of these proteoforms upon mechanical stimulation.

Beyond the quantitative view of these data, one advantage of top down MS is the preservation of the relationship among amino acid sequence, cleavage sites, and post-translational modifications. Examples of where these proteoform analyses provide specific whole-protein level information that would be more challenging to obtain through a bottom-up strategy include the specific detection of the B-Box of HMGB1, two proteoforms of B2M which differ by a single amino acid substitution, unmodified full-length and modified truncated DBI, cleavage products of CALM4, and CALM1 proteoforms containing either acetylation or trimethylation. Although the biological function of these modified proteoforms is not yet known, this quantitative discovery approach sets the stage for future studies aimed at precisely relating whole-level protein information to mechanotransduction.

While the method used here establishes the utility of top down MS for discovering novel factors involved in mechanotransduction, there are limitations. From a technical perspective, there is a preference for identification of proteoforms <25 kDa using the Q Exactive MS and fragmentation is limited to higher energy collision dissociation (HCD); however, these limitations can be overcome with more advanced instrumentation 78–79. Moreover, depth of coverage may be increased if a deglycosylation step prior to MS were performed, as many secreted proteins are N-glycosylated and this post-translational modification can complicate top down MS analysis. From a biological perspective, it is not possible to attribute the proteins identified here to their cellular origin, as skin contains not only keratinocytes, but other cell types including Merkel cells, fibroblasts, mast cells, dendritic cells, Langerhans cells, and sensory neurons.

Despite these limitations, these proof-of-concept data demonstrate that this approach can rapidly identify targets of interest for future studies that could include comparisons among larger sampling groups, ranges of stimulation intensities, variations in type of force applied (e.g. dynamic versus static), and furthermore, determine whether a tissue injury model would induce the release of other novel molecules or increase the release of the molecules identified in baseline non-in vivo-injured tissue. In conclusion, this proof-of-concept study shows that analysis of supernatant from mechanically stimulated naïve mouse skin by top down MS can reveal proteoforms not previously described as having a role in mechanotransduction and establishes a baseline of the proteome released from skin in response to tactile stimulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01-NS040538 and R01-NS070711 to CLS; R01-HL126785 and R01-HL134010 to RLG; F31-HL140914 to MW]. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, data collection, interpretation, analysis or publication. We thank Drs. Ioanna Ntai, Richard LeDuc, Joseph Greer, Paul Thomas, Phil Compton, and Ryan Fellers at Northwestern University for guidance regarding top down data collection and analysis. Special thanks to Tara Schroeder and David Horn at Thermo Fisher Scientific for assistance with BioPharma Finder.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The following supporting information is available free of charge at ACS website: https://urldefense.proofpoint.com/v2/url?u=http-3A__pubs.acs.org&d=DwICaQ&c=aFamLAsxMIDYjNglYHTMV0iqFn3z4pVFYPQkjgspw4Y&r=9IRmljuelwkoD3yAjnCgRA&m=kXOlIcADkpn0SedfPioiT0C9xDlZkz5NUzgqRdbXHbM&s=_5_N7pN2GEl1Rt3b2vR22Mttxhzaxr5MyCXyFKe5moA&e=

References

- 1.Chateau Y; Misery L, Connections between nerve endings and epidermal cells: are they synapses? Exp Dermatol 2004, 13 (1), 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chateau Y; Dorange G; Clement JF; Pennec JP; Gobin E; Griscom L; Baudrimont M; Rougier N; Chesne C; Misery L, In vitro reconstruction of neuro-epidermal connections. J Invest Dermatol 2007, 127 (4), 979–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coste B; Mathur J; Schmidt M; Earley TJ; Ranade S; Petrus MJ; Dubin AE; Patapoutian A, Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science 2010, 330 (6000), 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranade SS; Woo SH; Dubin AE; Moshourab RA; Wetzel C; Petrus M; Mathur J; Begay V; Coste B; Mainquist J; Wilson AJ; Francisco AG; Reddy K; Qiu Z; Wood JN; Lewin GR; Patapoutian A, Piezo2 is the major transducer of mechanical forces for touch sensation in mice. Nature 2014, 516 (7529), 121–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fradette J; Larouche D; Fugere C; Guignard R; Beauparlant A; Couture V; CaouetteLaberge L; Roy A; Germain L, Normal human Merkel cells are present in epidermal cell populations isolated and cultured from glabrous and hairy skin sites. J Invest Dermatol 2003, 120 (2), 313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halata Z; Grim M; Bauman KI, Friedrich Sigmund Merkel and his “Merkel cell”, morphology, development, and physiology: review and new results. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 2003, 271 (1), 225–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moll I; Moll R; Franke WW, Formation of epidermal and dermal Merkel cells during human fetal skin development. J Invest Dermatol 1986, 87 (6), 779–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maksimovic S; Nakatani M; Baba Y; Nelson AM; Marshall KL; Wellnitz SA; Firozi P; Woo SH; Ranade S; Patapoutian A; Lumpkin EA, Epidermal Merkel cells are mechanosensory cells that tune mammalian touch receptors. Nature 2014, 509 (7502), 617–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo SH; Ranade S; Weyer AD; Dubin AE; Baba Y; Qiu Z; Petrus M; Miyamoto T; Reddy K; Lumpkin EA; Stucky CL; Patapoutian A, Piezo2 is required for Merkel-cell mechanotransduction. Nature 2014, 509 (7502), 622–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda R; Cha M; Ling J; Jia Z; Coyle D; Gu JG, Merkel cells transduce and encode tactile stimuli to drive Abeta-afferent impulses. Cell 2014, 157 (3), 664–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang W; Kanda H; Ikeda R; Ling J; DeBerry JJ; Gu JG, Merkel disc is a serotonergic synapse in the epidermis for transmitting tactile signals in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113 (37), E5491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baumbauer KM; DeBerry JJ; Adelman PC; Miller RH; Hachisuka J; Lee KH; Ross SE; Koerber HR; Davis BM; Albers KM, Keratinocytes can modulate and directly initiate nociceptive responses. Elife 2015, 4, e09674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moehring F; Cowie AM; Menzel AD; Weyer AD; Grzybowski M; Arzua T; Geurts AM; Palygin O; Stucky CL, Keratinocytes mediate innocuous and noxious touch via ATP-P2X4 signaling. Elife 2018, 7, e31684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilceanu D; Stucky CL, TRPA1 mediates mechanical currents in the plasma membrane of mouse sensory neurons. PLoS One 2010, 5 (8), e12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranade SS; Syeda R; Patapoutian A, Mechanically Activated Ion Channels. Neuron 2015, 87 (6), 1162–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr TP; Albrecht PJ; Hou Q; Mongin AA; Strichartz GR; Rice FL, Air-stimulated ATP release from keratinocytes occurs through connexin hemichannels. PLoS One 2013, 8 (2), e56744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koizumi S; Fujishita K; Inoue K; Shigemoto-Mogami Y; Tsuda M; Inoue K, Ca2+ waves in keratinocytes are transmitted to sensory neurons: the involvement of extracellular ATP and P2Y2 receptor activation. Biochem J 2004, 380 (Pt 2), 329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou Q; Barr T; Gee L; Vickers J; Wymer J; Borsani E; Rodella L; Getsios S; Burdo T; Eisenberg E; Guha U; Lavker R; Kessler J; Chittur S; Fiorino D; Rice F; Albrecht P, Keratinocyte expression of calcitonin gene-related peptide beta: implications for neuropathic and inflammatory pain mechanisms. Pain 2011, 152 (9), 2036–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grando SA; Kist DA; Qi M; Dahl MV, Human keratinocytes synthesize, secrete, and degrade acetylcholine. J Invest Dermatol 1993, 101 (1), 32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakabayashi M; Hasegawa T; Yamaguchi T; Funakushi N; Suto H; Ueki R; Kobayashi H; Ogawa H; Ikeda S, Yokukansan, a traditional Japanese medicine, adjusts glutamate signaling in cultured keratinocytes. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014 (Article ID 364092), 7 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillbro JM; Marles LK; Hibberts NA; Schallreuter KU, Autocrine catecholamine biosynthesis and the beta-adrenoceptor signal promote pigmentation in human epidermal melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2004, 123 (2), 346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marconi A; Terracina M; Fila C; Franchi J; Bonte F; Romagnoli G; Maurelli R; Failla CM; Dumas M; Pincelli C, Expression and function of neurotrophins and their receptors in cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2003, 121 (6), 1515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grone A, Keratinocytes and cytokines. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2002, 88 (1–2), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith LM; Kelleher NL; Consortium for Top Down, P., Proteoform: a single term describing protein complexity. Nat Methods 2013, 10 (3), 186–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toby TK; Fornelli L; Kelleher NL, Progress in Top-Down Proteomics and the Analysis of Proteoforms. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2016, 9 (1), 499–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koltzenburg M; Stucky CL; Lewin GR, Receptive properties of mouse sensory neurons innervating hairy skin. J Neurophysiol 1997, 78 (4), 1841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwan KY; Glazer JM; Corey DP; Rice FL; Stucky CL, TRPA1 modulates mechanotransduction in cutaneous sensory neurons. J Neurosci 2009, 29 (15), 4808–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lennertz RC; Kossyreva EA; Smith AK; Stucky CL, TRPA1 mediates mechanical sensitization in nociceptors during inflammation. PLoS One 2012, 7 (8), e43597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zappia KJ; Garrison SR; Palygin O; Weyer AD; Barabas ME; Lawlor MW; Staruschenko A; Stucky CL, Mechanosensory and ATP Release Deficits following Keratin14-CreMediated TRPA1 Deletion Despite Absence of TRPA1 in Murine Keratinocytes. PLoS One 2016, 11 (3), e0151602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandilands A; Sutherland C; Irvine AD; McLean WH, Filaggrin in the frontline: role in skin barrier function and disease. J Cell Sci 2009, 122 (Pt 9), 1285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinac B; Adler J; Kung C, Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature 1990, 348 (6298), 261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moe P; Blount P, Assessment of potential stimuli for mechano-dependent gating of MscL: effects of pressure, tension, and lipid headgroups. Biochemistry 2005, 44 (36), 12239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sukharev SI; Blount P; Martinac B; Blattner FR; Kung C, A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature 1994, 368 (6468), 265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang Z; Sakamoto T; Tiwari V; Kim YS; Yang F; Dong X; Guler AD; Guan Y; Caterina MJ, Selective keratinocyte stimulation is sufficient to evoke nociception in mice. Pain 2015, 156 (4), 656–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basbaum AI; Bautista DM; Scherrer G; Julius D, Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009, 139 (2), 267–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KE; Wulff BC; Oberyszyn TM; Wilgus TA, Ultraviolet light exposure stimulates HMGB1 release by keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res 2013, 305 (9), 805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agalave NM; Svensson CI, Extracellular high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) as a mediator of persistent pain. Mol Med 2015, 20, 569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinagra T; Merlo S; Spampinato SF; Pasquale RD; Sortino MA, High mobility group box 1 contributes to wound healing induced by inhibition of dipeptidylpeptidase 4 in cultured keratinocytes. Front Pharmacol 2015, 6, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He SJ; Cheng J; Feng X; Yu Y; Tian L; Huang Q, The dual role and therapeutic potential of high-mobility group box 1 in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8 (38), 64534–64550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J; Kokkola R; Tabibzadeh S; Yang R; Ochani M; Qiang X; Harris HE; Czura CJ; Wang H; Ulloa L; Wang H; Warren HS; Moldawer LL; Fink MP; Andersson U; Tracey KJ; Yang H, Structural basis for the proinflammatory cytokine activity of high mobility group box 1. Mol Med 2003, 9 (1–2), 37–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sappington PL; Yang R; Yang H; Tracey KJ; Delude RL; Fink MP, HMGB1 B box increases the permeability of Caco-2 enterocytic monolayers and impairs intestinal barrier function in mice. Gastroenterology 2002, 123 (3), 790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eckert RL; Broome AM; Ruse M; Robinson N; Ryan D; Lee K, S100 proteins in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2004, 123 (1), 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Broome AM; Ryan D; Eckert RL, S100 protein subcellular localization during epidermal differentiation and psoriasis. J Histochem Cytochem 2003, 51 (5), 675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaya F; Decosterd I; Samad TA; Plumpton C; Tate S; Mannion RJ; Costigan M; Woolf CJ, Diversity of expression of the sensory neuron-specific TTX-resistant voltage-gated sodium ion channels SNS and SNS2. Mol Cell Neurosci 2000, 15 (4), 331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shields SD; Ahn HS; Yang Y; Han C; Seal RP; Wood JN; Waxman SG; Dib-Hajj SD, Nav1.8 expression is not restricted to nociceptors in mouse peripheral nervous system. Pain 2012, 153 (10), 2017–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao P; Barr TP; Hou Q; Dib-Hajj SD; Black JA; Albrecht PJ; Petersen K; Eisenberg E; Wymer JP; Rice FL; Waxman SG, Voltage-gated sodium channel expression in rat and human epidermal keratinocytes: evidence for a role in pain. Pain 2008, 139 (1), 90–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mischke D; Korge BP; Marenholz I; Volz A; Ziegler A, Genes encoding structural proteins of epidermal cornification and S100 calcium-binding proteins form a gene complex (“epidermal differentiation complex”) on human chromosome 1q21. J Invest Dermatol 1996, 106 (5), 989–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simonet WS; Bucay N; Pitas RE; Lauer SJ; Taylor JM, Multiple tissue-specific elements control the apolipoprotein E/C-I gene locus in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem 1991, 266 (14), 8651–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jong MC; Gijbels MJ; Dahlmans VE; Gorp PJ; Koopman SJ; Ponec M; Hofker MH; Havekes LM, Hyperlipidemia and cutaneous abnormalities in transgenic mice overexpressing human apolipoprotein C1. J Clin Invest 1998, 101 (1), 145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagelkerken L; Verzaal P; Lagerweij T; Persoon-Deen C; Berbee JF; Prens EP; Havekes LM; Oranje AP, Development of atopic dermatitis in mice transgenic for human apolipoprotein C1. J Invest Dermatol 2008, 128 (5), 1165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westerterp M; Berbee JF; Delsing DJ; Jong MC; Gijbels MJ; Dahlmans VE; Offerman EH; Romijn JA; Havekes LM; Rensen PC, Apolipoprotein C-I binds free fatty acids and reduces their intracellular esterification. J Lipid Res 2007, 48 (6), 1353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahley RW; Innerarity TL; Rall SC Jr.; Weisgraber KH, Plasma lipoproteins: apolipoprotein structure and function. J Lipid Res 1984, 25 (12), 1277–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marques MA; Combes M; Roussel B; Vidal-Dupont L; Thalamas C; Lafontan M; Viguerie N, Impact of a mechanical massage on gene expression profile and lipid mobilization in female gluteofemoral adipose tissue. Obes Facts 2011, 4 (2), 121–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brewer HB Jr.; Lux SE; Ronan R; John KM, Amino acid sequence of human apoLpGln-II (apoA-II), an apolipoprotein isolated from the high-density lipoprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1972, 69 (5), 1304–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yokoyama S, Apolipoprotein-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. Biochim Biophys Acta 1998, 1392 (1), 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferraro JT; Daneshmand M; Bizios R; Rizzo V, Depletion of plasma membrane cholesterol dampens hydrostatic pressure and shear stress-induced mechanotransduction pathways in osteoblast cultures. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2004, 286 (4), C831–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu L; Matsuyama I; Chiba T; Xing Y; Korenaga T; Guo Z; Fu X; Nakayama J; Mori M; Higuchi K, Extrahepatic expression of apolipoprotein A-II in mouse tissues: possible contribution to mouse senile amyloidosis. J Histochem Cytochem 2001, 49 (6), 739–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng C; Lu Z; Xie Z; Cheng Z; Chen Y; Tan M; Luo H; Zhang Y; He W; Yang K; Zwaans BM; Tishkoff D; Ho L; Lombard D; He TC; Dai J; Verdin E; Ye Y; Zhao Y, The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol Cell Proteomics 2011, 10 (12), M111 012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Z; Tan M; Xie Z; Dai L; Chen Y; Zhao Y, Identification of lysine succinylation as a new post-translational modification. Nat Chem Biol 2011, 7 (1), 58–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirschey MD; Zhao Y, Metabolic Regulation by Lysine Malonylation, Succinylation, and Glutarylation. Mol Cell Proteomics 2015, 14 (9), 2308–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y; Ding YX; Ding J; Wu LY; Xue Y, Mal-Lys: prediction of lysine malonylation sites in proteins integrated sequence-based features with mRMR feature selection. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 38318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Denda M; Fuziwara S; Inoue K, Influx of calcium and chloride ions into epidermal keratinocytes regulates exocytosis of epidermal lamellar bodies and skin permeability barrier homeostasis. J Invest Dermatol 2003, 121 (2), 362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Denda M; Inoue K; Inomata S; Denda S, gamma-Aminobutyric acid (A) receptor agonists accelerate cutaneous barrier recovery and prevent epidermal hyperplasia induced by barrier disruption. J Invest Dermatol 2002, 119 (5), 1041–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang W; Wu DC; Chen YH; He W; Yu LC, Anti-nociceptive effects of diazepam binding inhibitor in the central nervous system of rats. Brain Res 2002, 956 (2), 393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duran JM; Anjard C; Stefan C; Loomis WF; Malhotra V, Unconventional secretion of Acb1 is mediated by autophagosomes. J Cell Biol 2010, 188 (4), 527–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Christian CA; Herbert AG; Holt RL; Peng K; Sherwood KD; Pangratz-Fuehrer S; Rudolph U; Huguenard JR, Endogenous positive allosteric modulation of GABA(A) receptors by diazepam binding inhibitor. Neuron 2013, 78 (6), 1063–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bloksgaard M; Neess D; Faergeman NJ; Mandrup S, Acyl-CoA binding protein and epidermal barrier function. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1841 (3), 369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knudsen J; Mandrup S; Rasmussen JT; Andreasen PH; Poulsen F; Kristiansen K, The function of acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP)/diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI). Mol Cell Biochem 1993, 123 (1–2), 129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rasmussen JT; Borchers T; Knudsen J, Comparison of the binding affinities of acyl-CoA-binding protein and fatty-acid-binding protein for long-chain acyl-CoA esters. Biochem J 1990, 265 (3), 849–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang M; Morasso MI, The novel murine Ca2+-binding protein, Scarf, is differentially expressed during epidermal differentiation. J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (48), 47827–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hwang J; Kalinin A; Hwang M; Anderson DE; Kim MJ; Stojadinovic O; Tomic-Canic M; Lee SH; Morasso MI, Role of Scarf and its binding target proteins in epidermal calcium homeostasis. J Biol Chem 2007, 282 (25), 18645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsutsumi M; Inoue K; Denda S; Ikeyama K; Goto M; Denda M, Mechanical-stimulation-evoked calcium waves in proliferating and differentiated human keratinocytes. Cell Tissue Res 2009, 338 (1), 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ehlers MD; Zhang S; Bernhadt JP; Huganir RL, Inactivation of NMDA receptors by direct interaction of calmodulin with the NR1 subunit. Cell 1996, 84 (5), 745–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ivanina T; Blumenstein Y; Shistik E; Barzilai R; Dascal N, Modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by gbeta gamma and calmodulin via interactions with N and C termini of alpha 1C. J Biol Chem 2000, 275 (51), 39846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarhan MF; Tung CC; Van Petegem F; Ahern CA, Crystallographic basis for calcium regulation of sodium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109 (9), 3558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Villalobo A; Ishida H; Vogel HJ; Berchtold MW, Calmodulin as a protein linker and a regulator of adaptor/scaffold proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2018, 1865 (3), 507–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kwon Y; Hofmann T; Montell C, Integration of phosphoinositide- and calmodulin-mediated regulation of TRPC6. Mol Cell 2007, 25 (4), 491–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cai W; Tucholski T; Chen B; Alpert AJ; McIlwain S; Kohmoto T; Jin S; Ge Y, TopDown Proteomics of Large Proteins up to 223 kDa Enabled by Serial Size Exclusion Chromatography Strategy. Anal Chem 2017, 89 (10), 5467–5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riley NM; Westphall MS; Coon JJ, Sequencing Larger Intact Proteins (30–70 kDa) with Activated Ion Electron Transfer Dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 2018, 29 (1), 140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.