Abstract

Objective:

The Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system identified suicide prevention as a top priority and established policies to include high-risk suicide patient record flags (PRFs) in the electronic medical record to alert providers of patient risk and increase healthcare contacts. This study identified predictors of new PRFs and described healthcare utilization before and after PRF initiation among VA patients with substance use disorders.

Methods:

The sample included patients ages 18 and older who received a substance use disorder diagnosis in 2012 (N=474,946). Demographic, clinical and utilization predictors of PRFs were identified using multivariable logistic regression. Changes in short-term (3-months) and longer-term (12 months) healthcare utilization before and after PRF activation were compared using negative binomial regression.

Results:

A total of 8,913 patients received PRFs. Demographic predictors of PRF initiation included being younger than 35, White, and homeless. Clinical predictors were cocaine, opioid and sedative use disorders, posttraumatic stress, psychotic, bipolar, and depressive disorders, and suicide-attempt diagnoses. Patients with PRFs averaged 1.33 (95%Confidence Interval (CI): 3.80–4.42) times more primary care, 2.29 (95%CI: 2.242.34) times more mental health, 4.10 (95%CI: 3.80–4.42) times more substance use clinic visit days, and fewer (.55, 95%CI: .53–.58) emergency department visit days in the 3 months following compared to 3 months before PRF initiation. Modest increases in mental health and substance use-related days hospitalized were observed.

Conclusion:

Veterans identified with PRFs received significantly more healthcare services after PRF initiation. Further research is warranted on the effects of PRFs on clinical outcomes, such as suicide behaviors.

Introduction

Despite representing only 8% of the US adult population (1), veterans account for 18% of all US deaths by suicide and are at 21% greater risk for death by suicide than members of the general population (2). Additionally, suicide attempts are on the rise among veterans, increasing from approximately 600 per month in May 2012 to approximately 900 per month in August 2014 (3). Prior suicide attempts are robust predictors of future suicide (4), and suicide attempts are associated with additional healthcare needs (5), follow-up care (6), safety planning, and stress for both patients and providers (7).

Individuals with substance use disorders are at particularly high-risk for suicide. The risk of suicide is 7.5 times higher in males and 11.7 times higher in females with substance use disorders or mental health disorders compared to individuals without either disorder (8). The rate of suicide among veterans with a substance use disorder in 2014 was approximately 89 per 100,000 (2), the second-highest suicide rate among mental health categories. Veterans with opioid use disorders are at even greater risk, with a suicide rate of approximately 140 per 100,000 (2). Alcohol misuse is also associated with an increased risk for suicide (approximately 77 cases per 100,000) (9).

The US Secretary of Veterans Affairs (VA) has identified suicide prevention as the VA’s top clinical priority (10), and efforts have been ongoing for the last decade to identify and respond to veterans at high-risk for suicide. Electronic medical record (EMR) systems provide one opportunity to improve suicide prevention. Electronic flags and triggers have been used to alert providers to a variety of clinical needs and prevention opportunities (11–14). The VA has implemented such tools in a number of areas, including alerting providers to veterans’ suicide risk through High-risk for Suicide Patient Record Flags (PRFs) (15). By policy, the placement of a PRF is a clinical judgment based on an evaluation of risk factors, protective factors, and warning signs. However, the policy included five “indicators that a veteran may be considered high-risk” to improve uniform implementation (e.g., verified suicide attempt, hospitalization for suicidal ideation) (15). When a flag is in effect, providers are alerted immediately upon entry into the EMR that the patient has been identified as highrisk for suicide. In addition, mental health or substance use disorder treatment providers are expected to have contact with flagged veterans at least weekly in the month following PRF activation (16). Monthly clinical contact is recommended thereafter for PRF’s duration, which is typically three months, pending re-evaluation. The expectation for six clinical contacts was included in VA facility-level accountability metrics during the study period. While other integrated health care systems are using EMR data to flag patients for suicide interventions (17), to our knowledge, no study has evaluated the impact of such policies on patient care, particularly among veteran patients with documented substance use disorders.

The present study examined new PRF activation among veterans with documented substance use disorders in VA nationally. Specifically, the aims of this study are to: 1) identify demographic, clinical and service utilization predictors of new PRF activation; and 2) describe changes in short-term (3 month) and longer-term (1 year) utilization of outpatient and inpatient services before and after new PRF activation among veterans with substance use disorders.

Method

Source of Data and Study Population

This study used administrative medical records data from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), a national data repository that includes patient-level data on VA service utilization, as well as demographics and clinical diagnoses. VA patients aged 18 or older with a documented primary or secondary diagnosis of substance use disorder (excluding tobacco) from an outpatient or inpatient contact at a VA facility between October 1, 2011 and September 30, 2012 (FY12) were eligible for study inclusion (n=485,394). Diagnoses were identified using the Internal Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for alcohol, opioid, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, sedative, and other substance use disorders.

Patients were classified as having a PRF if a new PRF was placed in their EMR in the one year after their initial substance use disorder diagnosis (hereafter referred to as the index year). Patients with PRFs in their EMR in the year prior to their initial substance use disorder diagnosis (hereafter referred to as the baseline year) were excluded (n=10,448). Patients who died in the index year (n=14,541; no PRF: n=14,366, PRF: n=175) were included in predictors of PRF initiation analyses but not in utilization analyses given that their index year utilization would be truncated.

Study approval was obtained from the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board.

Predictors of PRF Initiation

Predictors of PRF initiation were identified from administrative data in the year prior to patients’ initial substance use disorder diagnoses, rather than the PRF initiation date, to ensure equivalent comparison periods between veterans with and without PRFs.

Demographic characteristics included age, race, ethnicity, marital status, engagement in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF), homeless status, and VA service-connected disability rating ≥50% (i.e., injury or illness incurred or aggravated during active military service, which determines VA health care eligibility and benefits).

Clinical characteristics included substance use disorder diagnoses (listed above), mental health, suicide-related and pain diagnoses, and medical comorbidity which were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes. Mental health diagnostic categories included post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety, depressive, bipolar, and psychotic disorders. A suicide attempt-related diagnosis was determined by one or more ICD-9-CM code (E95.X). The presence of a pain diagnosis was determined by at least one ICD-9-CM chronic pain diagnostic code (18). Medical comorbidity was calculated from ICD-9-CM codes using the modified (19) Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (20). CCI scores were assigned to three groups: 0, 1, ≥2, with higher scores reflecting greater comorbidity severity.

Any use of VA outpatient services in the baseline year was determined by outpatient clinic codes representing mental health, substance use disorder, primary care, and emergency department (ED) visits. VA inpatient service utilization was measured by any admission to acute inpatient medical, mental health, and substance use disorder-related (e.g., detoxification) services, as determined by inpatient bed codes.

Service Utilization Before and After PRF

As the initial activation period for suicide risk PRFs is three months, we were primarily interested in utilization changes in the three months preceding versus following PRF activation. To understand the impact of PRFs on longer-term utilization, changes in the one year preceding and following PRF activation also were examined. Outpatient utilization was measured by counts of visit days in mental health, substance use disorder, primary care and ED clinics. Inpatient utilization was measured by total days inpatient in acute medical, mental health and substance use disorder services based on admission and discharge dates. Outpatient visits and inpatient stays that included the PRF initiation date were excluded from visit counts and total inpatient days, respectively, as we could not determine if utilization was the result or the cause of PRF activation. Veterans without active PRFs or who died in the index year were excluded from these analyses.

To assess the proportion of patients with a PRF who met visit targets per VA policy (16) we created a binary variable indicating whether patients received mental health/substance use disorder care on ≥4 visit days in month 1 and ≥1 visit days in each of months 2 and 3.

Data Analysis

Demographics, baseline clinical characteristics and baseline utilization among those with and without a suicide risk PRF are presented using frequencies and percentages and compared using chi-square tests. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify characteristics associated with PRF initiation and estimate adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) among the full sample. The model included all predictors of PRF initiation mentioned above and was estimated with robust variance estimates to account for correlation between observations at the VA facility level.

Among patients with activated PRFs, the number of inpatient days (medicine, psychiatric, and substance use disorder-related) and outpatient visit days (mental health, substance use disorder, primary care, ED) in the three months and one year preceding and following PRF initiation were compared using unadjusted negative binomial regression models and estimated with incidence rate ratios and 95% CIs. In exploratory analyses, we utilized multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors associated with meeting visit targets (≥4 mental health/substance use disorder visit days in month 1 and ≥1 visit days in both months 2 and 3 post-PRF initiation); factors included demographics and clinical characteristics identified above in the year prior to PRF Page 7 of 23 initiation. To account for multiple comparisons, we adopted a p value threshold of p < .001. All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.0.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Among veterans with a substance use disorder in FY12 (N=474,946), 8,913 (1.9%) had a suicide risk PRF initiated in the index year. The majority of the full sample was male, aged 45 or older, White, and of non-Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (see Table 1). The most common substance use disorder and mental health disorder were alcohol use and depressive disorders, respectively, and the majority had a pain-related diagnosis.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of veterans with substance use disorders, with and without suicide risk patient record flags (N = 474,946)

| No Suicide Risk Flag | Suicide Risk Flag | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=466,033 | n=8,913 | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||

| <35 | 51,738 | 11.1 | 2,155 | 24.2 |

| 35–44 | 41,435 | 8.9 | 1,310 | 14.7 |

| 45–54 | 104,661 | 22.5 | 2,554 | 28.7 |

| 55–64 | 186,685 | 40.1 | 2,402 | 27.0 |

| 65+ | 81,514 | 17.5 | 492 | 5.5 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 306,431 | 65.8 | 6,400 | 71.8 |

| Black | 114,531 | 24.6 | 1,649 | 18.5 |

| Other | 21,460 | 4.6 | 479 | 5.4 |

| Unknown | 23,611 | 5.1 | 385 | 4.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 405,402 | 87.0 | 7,681 | 86.2 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 30,980 | 6.7 | 862 | 9.7 |

| Unknown | 29,651 | 6.4 | 370 | 4.2 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 20,915 | 4.5 | 699 | 7.8 |

| Male | 445,118 | 95.5 | 8,214 | 92.2 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Not Married | 313,712 | 67.3 | 6,332 | 71.0 |

| Married | 149,316 | 32.0 | 2,528 | 28.4 |

| Unknown | 3,005 | 0.6 | 53 | 0.6 |

| OEF/OIF | 54,056 | 11.6 | 2,066 | 23.2 |

| Service Connected ≥50% | 114,360 | 24.5 | 2,435 | 27.3 |

| Homeless Baseline | 74,831 | 16.1 | 2,488 | 27.9 |

| Substance Use Diagnosis Baseline | ||||

| Alcohol Disorder | 361,226 | 77.5 | 6,719 | 75.4 |

| Cannabis Disorder | 75,548 | 16.2 | 2,157 | 24.2 |

| Cocaine Disorder | 70,419 | 15.1 | 2,111 | 23.7 |

| Amphetamine Disorder | 11,728 | 2.5 | 474 | 5.3 |

| Opioid Disorder | 43,314 | 9.3 | 1,457 | 16.4 |

| Sedative Disorder | 8,073 | 1.7 | 479 | 5.4 |

| Other Substance Use Disorder | 85,914 | 18.4 | 2,387 | 26.8 |

| Any Drug Use Disorder | 205088 | 44.0 | 5447 | 61.1 |

| Mental Health Diagnosis Baseline | ||||

| Depressive Disorder | 180,377 | 38.7 | 5,231 | 58.7 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 130,112 | 27.9 | 3,751 | 42.1 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 86,584 | 18.6 | 2,641 | 29.6 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 37,392 | 8.0 | 1,761 | 19.8 |

| Psychotic Disorder | 33,253 | 7.1 | 1,151 | 12.9 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Score* | ||||

| 0 | 256,137 | 55.0 | 5,482 | 61.5 |

| 1 | 163,929 | 35.2 | 2,679 | 30.1 |

| ≥2 | 45,967 | 9.9 | 752 | 8.4 |

| Pain-Related Diagnosis Baseline | 291,180 | 62.5 | 5,963 | 66.9 |

| Suicide Attempt Diagnosis Baseline | 2,764 | 0.6 | 689 | 7.7 |

| Acute Inpatient Admissions Baseline | ||||

| Any Medical Admission | 39,282 | 8.4 | 903 | 10.1 |

| Any Psychiatric Admission | 14,371 | 3.1 | 1,042 | 11.7 |

| Any Substance Use Admission | 15,473 | 3.3 | 776 | 8.7 |

| Outpatient Visits Baseline | ||||

| Any Primary Care Visit | 421,793 | 90.5 | 7,301 | 81.9 |

| Any Mental Health Visit | 292,777 | 62.8 | 7,719 | 86.6 |

| Any Substance Use Visit | 98,476 | 21.1 | 2,537 | 28.5 |

| Any Emergency Department Visit | 167,171 | 35.9 | 5,410 | 60.7 |

Notes. ED = Emergency Department; OEF/OIF = Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom

All comparisons between patients with and without flags are significant at p < .001.

Tiers reflect patients’ total Charlson Comorbidity Index scores at baseline.

Predictors of PRF Initiation

Significant baseline year predictors of PRF initiation included age< 35, White, homeless, <50% service connected, and having served in OEF/OIF (Table 2). Any suicide attempt-related diagnosis in the baseline year was predictive of PRF initiation. Substance use disorder diagnoses that predicted suicide PRF initiation included cocaine, opioid, and sedative use disorders, while mental health disorder diagnoses included PTSD, and psychotic, bipolar, and depressive disorders. Any inpatient or outpatient mental health contact and ED visit predicted PRF initiation. Factors that protected against PRF initiation included any primary care or substance use disorder outpatient visit. Predictors of PRF initiation run separately for men and women are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical, and utilization predictors of suicide risk patient record flag initiation (N = 474,946).

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <35 | referent | ||

| 35–44 | 0.81 | 0.74 – 0.88 | * |

| 45–54 | 0.68 | 0.61 – 0.75 | * |

| 55–64 | 0.44 | 0.39 – 0.50 | * |

| 65+ | 0.28 | 0.23 – 0.33 | * |

| Race | |||

| White | referent | ||

| Black | 0.63 | 0.56 – 0.70 | * |

| Other | 0.93 | 0.84 – 1.04 | |

| Unknown | 0.79 | 0.67 – 0.94 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | referent | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.27 | 0.72 – 2.27 | |

| Unknown | 0.95 | 0.81 – 1.12 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | referent | ||

| Male | 0.97 | 0.88 – 1.06 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Not Married | referent | ||

| Married | 1.07 | 1.01 – 1.13 | |

| Unknown | 0.96 | 0.67 – 1.38 | |

| OEF/OIF | 1.19 | 1.09 – 1.31 | * |

| Service Connected ≥50% | 0.87 | 0.82 – 0.93 | * |

| Homeless Baseline | 1.22 | 1.10 – 1.35 | * |

| Substance Use Diagnosis Baseline | |||

| Alcohol Disorder | 1.04 | 0.97 – 1.11 | |

| Cannabis Disorder | 1.00 | 0.94 – 1.07 | |

| Cocaine Disorder | 1.34 | 1.21 – 1.49 | * |

| Amphetamine Disorder | 1.08 | 0.93 – 1.25 | |

| Opioid Disorder | 1.18 | 1.09 – 1.28 | * |

| Sedative Disorder | 1.45 | 1.22 – 1.72 | * |

| Other Substance Use Disorder | 0.97 | 0.90 – 1.05 | |

| Mental Health Diagnosis Baseline | |||

| Depressive Disorder | 2.57 | 2.41 – 2.74 | * |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 1.22 | 1.10 – 1.35 | * |

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.06 | 1.01 – 1.11 | |

| Bipolar Disorder | 3.04 | 2.78 – 3.32 | * |

| Psychotic Disorder | 1.33 | 1.22 – 1.46 | * |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Score** | |||

| 0 | referent | ||

| 1 | 1.01 | 0.95 – 1.07 | |

| ≥2 | 1.10 | 1.01 – 1.19 | |

| Pain-Related Diagnosis Baseline | 1.08 | 1.03 – 1.13 | |

| Suicide Attempt Diagnosis Baseline | 5.71 | 4.95 – 6.59 | * |

| Acute Inpatient Admissions Baseline | |||

| Any Medical Admission | 0.9 | 0.84 – 0.97 | |

| Any Psychiatric Admission | 1.23 | 1.11 – 1.36 | * |

| Any Substance Use Admission | 1.03 | 0.91 – 1.16 | |

| Outpatient Visits Baseline | |||

| Any Primary Care Visit | 0.51 | 0.48 – 0.55 | * |

| Any Mental Health Visit | 1.52 | 1.36 – 1.70 | * |

| Any Substance Use Visit | 0.83 | 0.77 – 0.90 | * |

| Any Emergency Department Visit | 2.01 | 1.83 – 2.20 | * |

| constant | 0.01 | 0.01 – 0.02 | |

Notes. ED = Emergency Department. OEF/OIF = Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom; CI = Confidence Interval

p < .001.

Tiers reflect patients’ total Charlson Comorbidity Index scores at baseline.

Service Utilization Before and After PRF

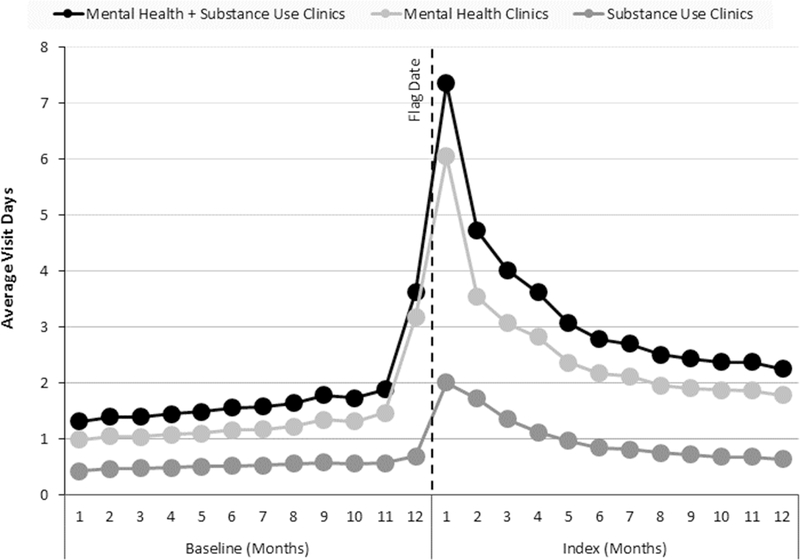

With the exceptions of ED visits and medical inpatient admissions, utilization increased during the three months following PRF initiation, compared with the prior three months (Table 3). Patients with a suicide risk PRF (n = 8,738; excludes 175 veterans with new PRFs who died in the index year) averaged 1.3 times more primary care, 2.3 times more mental health, and 4.1 times more substance use disorder visit days in the three months following PRF initiation, compared to the three months prior. Increases in days hospitalized were more modest; patients averaged 1.4 times more mental health and 1.3 times more substance use disorder hospitalized days in the three months following PRF initiation relative to the prior three months. ED visits decreased significantly, with patients averaging approximately one-half the number of ED visits in the three months after the PRF initiation relative to the three months prior. Medical inpatient admissions remained largely unchanged. Results comparing the one-year periods prior to and following PRF initiation were similar to 3-month results. Figure 1 shows an increase in outpatient mental health/substance use disorder treatment contacts immediately prior to PRF initiation, with visits continuing to rise sharply in month one following PRF initiation, and subsequently decreasing but remaining elevated in month 2, followed by a gradual decline over months 3 to 12. Of note, patients with PRFs averaged 12 contacts in the two months following PRF initiation, and utilization remained higher than the baseline months for up to one year after PRF initiation.

Table 3.

Outpatient and inpatient utilization before and after suicide risk patient record flag initiation (n = 8,738)

| Before Patient Record Flag | After Patient Record Flag | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | IRR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Outpatient utilization | ||||||||

| Primary care visits | 3 Months | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.33 | 1.29 – 1.38 | * |

| 1 Year | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 1.22 | 1.20 – 1.25 | * | |

| Mental health visits | 3 Months | 5.9 | 6.9 | 12.6 | 10.1 | 2.29 | 2.24 – 2.34 | * |

| 1 Year | 16.0 | 20.0 | 31.4 | 27.6 | 2.22 | 2.17 – 2.27 | * | |

| Substance use disorder visits | 3 Months | 1.8 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 9.6 | 4.10 | 3.80 – 4.42 | * |

| 1 Year | 6.3 | 15.5 | 12.2 | 22.1 | 1.98 | 1.84 – 2.13 | * | |

| Emergency department visits | 3 Months | 1.1 | 1.4 | .6 | 1.2 | .55 | .53 – .58 | * |

| 1 Year | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 3.2 | .83 | .80 – .85 | * | |

| Inpatient Utilization | ||||||||

| Medical days hospitalized | 3 Months | .3 | 1.8 | .4 | 3.0 | 1.27 | 1.05 – 1.52 | |

| 1 Year | 1.1 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 6.7 | 1.24 | 1.10 – 1.39 | * | |

| Mental health days hospitalized | 3 Months | 1.4 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 7.9 | 1.39 | 1.25 – 1.54 | * |

| 1 Year | 3.3 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 15.5 | 1.54 | 1.43 – 1.66 | * | |

| Substance use disorder days hospitalized | 3 Months | .7 | 3.1 | .9 | 4.3 | 1.30 | 1.15 – 1.48 | * |

| 1 Year | 1.9 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 8.7 | 1.41 | 1.30 – 1.53 | * | |

Notes: SD = Standard Deviation; IRR = Incidence Rate Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; PRF = Patient Record Flag

Analyses exclude patients who died in the year following PRF initiation (n=175). Visits occurring on date of flag activation are not included.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Average outpatient visit days by month, one year before and after activation of a suicide risk patient risk flag.

Note: Data reflect visit days in the 12 months prior to and following initial flag placement for each individual patient. Initial flag placement occurred between October 2011 and September 2013.

Overall, 82.5% (95% CI: 81.7 – 83.3%) of veterans attended six or more mental health and/or substance use clinic visits in months 1 to 3 following PRF initiation and 61.7% (95% CI: 60.7 – 62.7%) met specific VA visit targets (≥4 mental health and/or substance use disorder treatment contacts in month 1, ≥1 treatment contacts in each of months 2 and 3), with 14.3% (13.6 – 15.0%) meeting targets in month 1 only, and 24.0% (23.1 – 24.9%) failing to meet targets. Homelessness, bipolar diagnosis, and age 45 to 54 (relative to <35) were associated with greater likelihood of meeting visit targets.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine VA service utilization before and after initiation of a suicide patient risk flag. According to VA policy, patients with new suicide risk flags are expected to have weekly clinical contacts during the first month after PRF initiation, with monthly visits encouraged thereafter. Consistent with this policy, 62% of patients with new flags attended the recommended number of visits in months 1 to 3, with an additional 14% meeting recommended targets in month 1 only. Further, outpatient contacts in mental health and substance use disorder clinics increased 2.3 and 4.1 times, respectively, over the three-month follow-up period, with mean contacts in these services exceeding the minimum required one contact per week in month one. In contrast, ED visits decreased by 45% in the 3 months following initiation of a PRF.

Although this study was not able to assess the impact of increased clinical contacts on subsequent suicidal-related behaviors, reductions in suicide-related behaviors have been reported by studies of similar aftercare interventions. Interventions that aim to engage individuals after a suicide attempt, using weekly to semi-monthly contacts, have shown reductions in both suicide attempts and suicides (21, 22), and health care systems implementing suicide prevention policies that increased assessment and outreach have seen decreased suicide rates (23). Additional research is needed to determine whether increased mental health utilization following initiation of PRFs is associated with decreased suicide behaviors and other adverse outcomes in the VA health care system.

Of patients with suicide risk PRFs, 17% received fewer than 6 clinical contacts and 38% failed to meet specific VA visit targets in months 1 to 3 following PRF initiation (16). Several possibilities may account for this finding, including patients not attending follow-up visits, difficulty accessing care in rural areas (24), relocating out of the area, unwillingness to participate in after care, incapacitating illness, or other barriers to care (e.g., transportation difficulties, incarceration) (22). It is also possible that some veterans who initially received a PRF improved rapidly or were determined to be at lower risk and in need of fewer and less frequent contacts. It is notable that patients meeting visit targets were more likely to have a bipolar diagnosis, a more severe mental health disorder, or to be homeless, suggesting that providers allocated additional resources to those with significant psychiatric or psychosocial challenges.

Several predictors of suicide risk PRFs observed in this study have been identified as risk factors for suicide in the literature. White race and younger age are associated with suicide among veterans (3). Studies report an increased risk of suicide behaviors among those with social disadvantages, such as lack of education, poverty and unemployment (25–27), and suicide rates are elevated among homeless veterans (28). Our finding that alcohol use disorders did not predict initiation of suicide risk PRF was surprising given the significant body of research indicating that they are important risk factors for suicide (19–21). Our results may be due to limiting our cohort to patients with substance use disorders. Consistent with prior research on suicides and suicide behavior (4, 29), prior suicide attempts and psychiatric disorders such as PTSD and depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders were predictive of suicide risk PRF initiation. Taken together, most of the correlates of PRF initiation align with known risk factors for suicide and reinforce the importance of prevention strategies among groups with financial problems, prior suicide-related behavior and substance use and mental health disorders.

Implications

Overall, study findings suggest implementation of suicide risk PRFs in an electronic medical record and subsequent follow-up is feasible even in healthcare systems as diverse as the VA, which may be encouraging to other healthcare systems interested in implementing a similar approach. Providers appear to make prudent decisions regarding new PRFs activations, as approximately two percent of patients with substance use disorders were flagged for high-risk suicide. Further, the majority of patients with new PRFs received care compliant with VA policy.

Limitations

These analyses have several important limitations, primary among them that PRF activation is a subjective, clinical decision, and may vary regionally or by individuals initiating such flags. Our data did not allow us to determine the specialty or type of provider who initiated the risk flag, thus we cannot comment on whether particular provider groups or clinics are responding differently to this VA initiative. Data on suicides or suicide attempts, as well as on flag continuation or removal, following PRF activation were unavailable for analysis, preventing examination of the impact of increased health care utilization on these specific outcomes. In addition, use of administrative data limited the variables included in the predictive models, and potential differences on unmeasured variables (e.g. substance use disorder severity and pain severity) may have impacted study results. We did not have access to data on the quality of the health care visits. Our sample consisted of VA patients, and thus results may not generalize to non-veterans or veterans who receive care in the community. We did not include non-VA utilization, so patients’ use of services may be higher than reported here. Additionally, these analyses focused on veterans with substance use disorders, a high-risk population with specialized care needs, and therefore these results may not generalize to other veteran or non-veteran populations. The number of women was small and results may not generalize to this population. As the this was an observational study, changes in pre- and post-PRF utilization may be due to clinical procedures unrelated to PRF activation.

Conclusions

High-risk for suicide PRFs were implemented to identify and provide additional care to veterans perceived as being at increased risk for suicide. Results from analyses indicate that among veterans with substance use disorders, the use of PRFs was associated with increases in both outpatient and inpatient mental health and substance use disorder clinical contact, suggesting that once identified, these veterans significantly increase their service use within the VA health care system. Further research is needed on the effects of PRF activation and increased care on clinical outcomes, such as suicide behaviors. In addition, the research should be expanded to examine clinical contacts among veterans without substance use disorders. Although more work is needed, these encouraging results support the use of PRFs for the important goal of suicide prevention among veterans.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Demographic and clinical predictors of meeting visit targets (4 visit days in month 1, 1 visit days each in months 2 and 3; n=8738)

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <35 | |||

| 35–44 | 1.23 | 1.04 – 1.44 | |

| 45–54 | 1.38 | 1.17 – 1.62 | * |

| 55–64 | 1.25 | 1.05 – 1.48 | |

| 65+ | 1.03 | 0.82 – 1.31 | |

| Race | |||

| White | |||

| Black | 0.92 | 0.81 – 1.04 | |

| Other | 1.00 | 0.82 – 1.22 | |

| Unknown | 0.71 | 0.57 – 0.90 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.99 | 0.85 – 1.15 | |

| Unknown | 0.91 | 0.73 – 1.15 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | |||

| Male | 0.99 | 0.84 – 1.17 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | |||

| Not Married | 0.96 | 0.87 – 1.07 | |

| Unknown | 0.75 | 0.20 – 2.84 | |

| OEF/OIF | 1.12 | 0.97 – 1.31 | |

| Service Connected ≥50% | 0.97 | 0.88 – 1.08 | |

| Homeless | 1.38 | 1.25 – 1.53 | * |

| Substance Use Diagnosis | |||

| Alcohol Disorder | 1.08 | 0.96 – 1.21 | |

| Cannabis Disorder | 1.08 | 0.97 – 1.19 | |

| Cocaine Disorder | 1.01 | 0.91 – 1.13 | |

| Amphetamine Disorder | 1.09 | 0.91 – 1.29 | |

| Opioid Disorder | 1.01 | 0.89 – 1.13 | |

| Sedative Disorder | 0.89 | 0.75 – 1.06 | |

| Other Substance Use Disorder | 1.00 | 0.90 – 1.10 | |

| Mental Health Diagnosis | |||

| Depressive Disorder | 1.24 | 1.07 – 1.43 | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 1.16 | 1.05 – 1.28 | |

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.06 | 0.96 – 1.16 | |

| Bipolar Disorder | 1.55 | 1.31 – 1.82 | * |

| Psychotic Disorder | 1.12 | 0.99 – 1.27 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Score** | |||

| 0 | |||

| 1 | 0.97 | 0.87 – 1.08 | |

| ≥2 | 0.86 | 0.73 – 1.01 | |

| Pain-Related Diagnosis | 0.94 | 0.85 – 1.04 | |

| constant | 0.88 | 0.66 – 1.16 | |

Notes. OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; OEF/OIF = Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation.

Analyses exclude patients who died in the year following PRF initiation (n=175).

p < .001.

Tiers reflect patients’ total Charlson Comorbidity Index scores.

Disclosures/Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or University of Washington.

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, the VA Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment & Education and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (#1R21AA02894–01A1).

Contributor Information

Joanna Berg, VA Puget Sound Health Care System - Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education, Seattle, Washington.

Carol A. Malte, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington

Mark A. Reger, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington

Eric James Hawkins, VA Puget Sound Health Care System - Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education Seattle, Washington.

References

- 1.United States Department of Veteran Affairs. Profile of Veterans: 2015: Data from the American Community Survey. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; 2017. [Available from: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2015.pdf]

- 2.United States Department of Veteran Affairs. Suicide among veterans and other Americans 2001–2014. Office of Suicide Prevention; 2016. [Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf.]

- 3.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016(241):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beghi M, Rosenbaum JF, Cerri C, et al. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: a literature review. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2013;9:1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman-Mellor SJ, Caspi A, Harrington H, et al. Suicide attempt in young people: a signal for longterm health care and social needs. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71(2):119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. mhGAP training manuals for the mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings-version 2.0 (for field testing). 2017. [Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44406/1/9789241548069_eng.pdf.

- 7.Ting L, Jacobson JM, Sanders S. Current levels of perceived stress among mental health social workers who work with suicidal clients. Social work. 2011;56(4):327–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Page A, Martin G, et al. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Social science & medicine. 2011;72(4):608–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. JAMA. 2013;310(5):496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Public Radio. 'The VA Is On A Path Toward Recovery,' Secretary Of Veterans Affairs Says 2017. [Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/03/30/521937557/the-va-is-on-a-pathtoward-recovery-secretary-of-veterans-affairs-says.%20Accessed%20November%2029,%202017.]

- 11.Wax DB, McCormick PJ, Joseph TT, et al. An Automated Critical Event Screening and Notification System to Facilitate Preanesthesia Record Review. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy DR, Meyer AN, Vaghani V, et al. Electronic Triggers to Identify Delays in Follow-Up of Mammography: Harnessing the Power of Big Data in Health Care. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahnazarian V, Karu E, Mehta P. Hepatitis C: improving the quality of screening in a community hospital by implementing an electronic medical record intervention. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):u208549 w3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malte CA, Berger D, Saxon AJ, et al. Electronic Medical Record Alert Associated with Reduced Opioid and Benzodiazepine Co-prescribing Among High-Risk Veteran Patients. Medical Care. 2018;56(2):171–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 2008–036, Use of Patient Record Flags to Identify Patients at High Risk for Suicide. 2008. [Available from: http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=1719.]

- 16.Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Operations and Management. Patients at High-Risk for Suicide. April 24, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mental Health Research Network. Do You Believe An Algorithm, Or Your Own Lying Eyes? 2017. [Available from: http://hcsrn.org/mhrn/en/Blog/item15.html.]

- 18.Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Kovas AE, et al. Short-term variability in outpatient pain intensity scores in a national sample of older veterans with chronic pain. Pain Medicine. 2015;16(5):855–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hvid M, Vangborg K, Sorensen HJ, et al. Preventing repetition of attempted suicide--II. The Amager project, a randomized controlled trial. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(5):292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan YJ, Chang WH, Lee MB, et al. Effectiveness of a nationwide aftercare program for suicide attempters. Psychol Med. 2013;43(7):1447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffey MJ, Coffey CE, Ahmedani BK. Suicide in a health maintenance organization population. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(3):294–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, et al. VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, et al. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):371–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borges G, Nock MK, Haro Abad JM, et al. Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1617–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agerbo E, Sterne JA, Gunnell DJ. Combining individual and ecological data to determine compositional and contextual socio-economic risk factors for suicide. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):451–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, et al. Suicidal Self‐Directed Violence Among Homeless US Veterans: A Systematic Review. Suicide and life-threatening behavior. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, et al. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.