Abstract

Purpose:

Although studies have demonstrated a protective role for benefit finding in psychological distress, little is known about how benefit finding leads to lower psychological distress. This study’s goal was to use a multiple mediator model to evaluate whether the effect of benefit-finding on depression was mediated by acceptance of cancer, acceptance of emotions, and received social support.

Methods:

One hundred seventy-four women recently diagnosed with gynecological cancer completed measures of perceived benefits from the cancer experience, acceptance-based strategies, social support, and depression. Using a cross-sectional approach, we analyzed a multiple mediator model with benefit-finding as the independent variable, depressive symptom severity as the outcome, and acceptance-based strategies and social support as mediators.

Results:

Acceptance-based strategies and social support significantly mediated the relationship between benefit-finding and depression. Emotional acceptance had the strongest mediational effect, controlling for the other two mediators.

Conclusions:

Helping women diagnosed with gynecological cancers identify benefits from their cancer experience may reduce depression by paving the way for them to accept their emotional reactions, accept life changes associated with cancer, and facilitate supportive reactions from family and friends. Future longitudinal research is needed to confirm whether gynecological cancer patients who perceive more benefits will feel less depressed later.

Background

Benefit finding has been defined as positive life changes that result from a stressful event such as the diagnosis of cancer [1–3]. Benefits typically consist of improved personal resources and qualities (e.g., greater personal resilience), closer relationships, and positive changes in life priorities and purpose (e.g., [4, 5]). Benefit finding has been conceptualized as an evolving coping process in which people work to develop greater meaning from stressful and traumatic experiences [6]. Benefit finding is considered a cognitive strategy for coping with a difficult stressor [1, 3, 7]. Among persons diagnosed with cancer, longitudinal studies have found that benefit finding develops soon after the diagnosis and changes over the first year (e.g., [8]). As time passes and benefits are fostered, it has been proposed that the process of benefit finding may result in actual positive changes in the person’s life [3].

The broader literature focusing on persons experiencing a traumatic life event is not entirely consistent with regard to the role of benefit finding in psychological outcomes. However, benefit finding has been consistently associated with positive psychological outcomes among persons diagnosed with cancer. The most consistent relationship for benefit finding and outcomes has been shown for its association with lower depressive symptoms. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that higher levels of benefit finding are associated with fewer depressive symptoms [3, 9–13]. In terms of other psychological outcomes, studies have shown that higher levels of benefit finding are associated with less anxiety [10, 14] and higher quality of life [11]. Because depressive symptoms have been the most consistently associated with benefit finding in prior work with cancer patients, we selected depressive symptoms as the primary outcome in this study. Depressive symptoms are a relevant outcome to study in the context of health-related quality of life and cancer because of their important role in health-related quality of life. First, depressive symptoms are commonly included in the measurement of health-related quality of life (see [15] for a review). Second, studies focusing on general population (e.g., [16, 17]) as well as studies focusing on cancer patients (e.g., [18–20] have shown that depressive symptoms are associated with a deterioration in quality of life, particularly in the areas of role and social functioning.

Although studies have demonstrated a protective role for benefit finding in distress, little is known about how benefit finding leads to lower distress. A clearer understanding of the underlying mechanisms for benefit finding would inform and potentially enhance clinical interventions that target benefit finding as a way to reduce distress among cancer patients (e.g., gratitude interventions; [21]. Understanding benefit finding’s mechanisms may also illuminate the theoretical foundations of benefit finding by demonstrating how it works. There have been a number of theoretical frameworks proposed to explain why benefit finding may be beneficial. One relevant approach used to understand benefit finding and its impact is the stress and coping framework [22, 23]. According to this framework, benefit finding is a reappraisal coping strategy in which the person ascribes positive meaning to a difficult experience [1, 3, 7]. This reappraisal reduces perceived harm and threat associated with the adverse experience and fosters other types of beneficial coping [1, 24–26].

Among the beneficial coping processes that might be fostered by benefit finding, accommodative coping strategies such as acceptance may be strong linked with benefit finding. Acceptance consists of accepting that the event has occurred as well as emotional acceptance, which is a willingness to feel one’s positive and negative emotions without trying to control, change, or reject these feelings. Acceptance of the event - in this case, the cancer diagnosis - has been consistently associated with less distress among cancer patients [11, 27, 28], including among women diagnosed with gynecological cancer [29]. Although less studied, emotional acceptance has been associated with less distress among cancer patients [27, 30].

A second possible mechanism underlying the association between benefit finding and lower distress is the response by one’s social network when a patient engages in benefit finding. Patients who find benefit in the cancer experience may discuss these realizations with others. During these discussions, they may present a balanced perspective on their cancer experience. During these discussions, patients would review the positive benefits of the cancer experience along with the challenges they are facing. If the benefits that are discussed with others are authentic - that is, if the patient actually perceives the benefits as real, and the patient is not portraying these benefits to present a positive façade to minimize negative responses - these interactions are more likely to solicit positive responses from others [31, 32]. In support of this hypothesis, qualitative work among women with breast cancer has indicated that benefit finding is positively correlated greater perceived social support [33]. In addition, prior work has illustrated that social support mediates the association between benefit finding and quality of life among adult caregivers of cancer patients [34].

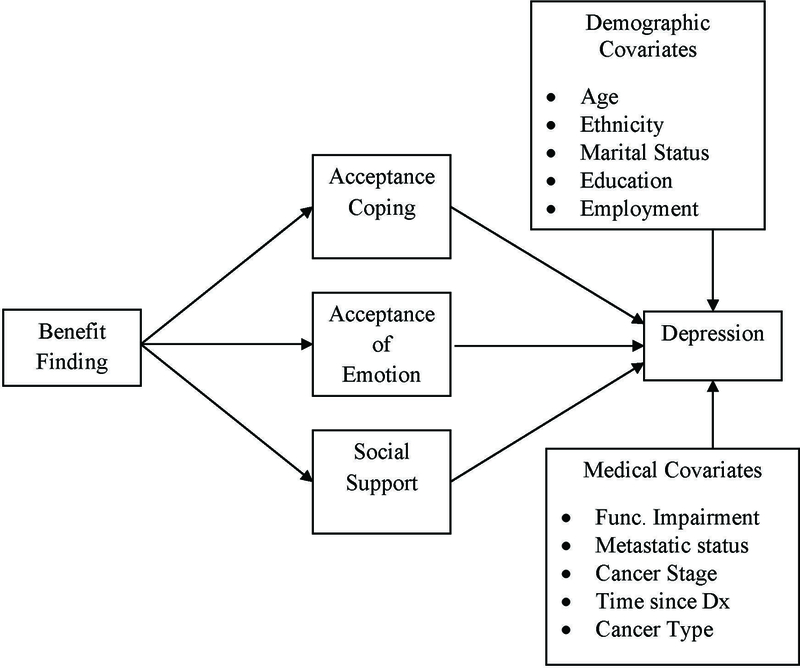

The primary aim of this study was to use a multiple mediator model to evaluate whether the effect of benefit finding on depression was mediated by acceptance of cancer, acceptance of emotions, and received social support (see Figure 1). We also examined an adjusted mediation model that controlled for demographic and medical correlates of depression to determine whether the effects of the three mediators on depression remained when the model included patient and medical characteristics. We utilized baseline data collected from newly-diagnosed gynecological cancer patients who participated in a randomized clinical trial [35] to test the model. A cross-sectional approach was used as a first step to provide preliminary support for the proposed mediation model.

Fig. 1.

Proposed parallel multiple mediation model of the relationship between benefit finding, depression, and three mediators (acceptance of emotion, acceptance of cancer, social support) and both demographic and medical covariates.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were women who were newly diagnosed with primary gynecological cancers (ovarian, endometrial, cervical, fallopian tube, or uterine cancer) and undergoing active medical treatment (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation) across seven hospitals in the northeastern United States. This cross-sectional study is a secondary data analysis, which utilized baseline (pre-intervention) data gathered between October 2012 to February 2016 from a randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of two psychological interventions [35]. Inclusion criteria were the following: at least 18 years of age, diagnosed with a gynecological cancer within the past six months from the time of recruitment, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) [36] score of 0 or 1 or a Karnofsky Performance Status [37] of at least 80, lived within a two-hour commuting distance from the recruitment site, fluently spoke English, and denied hearing impairment. Eligible women were identified via chart review, sent a letter describing the study, and contacted in person or by phone. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Women who completed baseline surveys were compensated $15.

Of the 1467 women approached to participate in the above-mentioned trial, 371 (25%) agreed to participate. For the purpose of this study, we included the 174 women who completed the Acceptance of Emotion Scale [27, 38], which was added after the trial was initiated. Refusal data for all women approached for the trial was published previously [35]. Compared to refusers, participants were younger, diagnosed within a shorter period of time, and more likely to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer [35]. Ethnic background, disease stage, and ECOG status were not different between participants and refusers.

Measures

Demographic and medical characteristics.

Participants reported their demographic information (age, ethnic background, education level, marital status, employment status) on baseline surveys. We gathered medical information (cancer type, cancer stage, metastatic status, time since diagnosis, time since surgical treatment) from medical charts.

Functional impairment

Functional impairment was assessed via the 26-item physical limitations subscale from the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES)[39]. CARES has been used to assess functional impairment in gynecological cancer patients in prior studies [35, 40]. Participants were instructed to rate how much the items applied to them within the past month on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = very much). Items included difficulties with eating, weight maintenance, ambulation, daily activities, leisure, and pain management. Internal consistency in the current study was .93.

Benefit finding.

Benefit finding was assessed via the 17-item Benefit Finding Scale [41, 42], which was employed in prior studies of gynecological cancer patients[43, 44]. Participants were asked to rate how much statements applied to them (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). Items on this scale are presented in Table 1. Benefits included both interpersonal and intrapersonal changes from cancer. Higher scores indicated perceiving more benefits from cancer. An average score was calculated. Internal consistency was .94.

Table 1.

Items for the Benefit-Finding Scale

| Item | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Having cancer… | |||

| Has led me to be more accepting of things. | 3.40 | 1.14 | 1–5 |

| Has taught me how to adjust to things I cannot change. | 3.43 | 1.15 | 1–5 |

| Has helped me take things as they come. | 3.44 | 1.14 | 1–5 |

| Has brought my family closer together. | 3.70 | 1.24 | 1–5 |

| Has made me more sensitive to family issues. | 3.44 | 1.24 | 1–5 |

| Has taught me that everyone has a purpose in life. | 3.13 | 1.47 | 1–5 |

| Has shown me that all people need to be loved. | 3.47 | 1.45 | 1–5 |

| Has made me realize the importance of planning for my family’s future. | 3.60 | 1.19 | 1–5 |

| Has made me more aware and concerned for the future of all human beings. | 3.10 | 1.36 | 1–5 |

| Has taught me to be patient. | 3.12 | 1.22 | 1–5 |

| Has led me to deal better with stress and problems. | 2.86 | 1.18 | 1–5 |

| Has led me to meet people who have become some of my best friends. | 2.27 | 1.34 | 1–5 |

| Has contributed to my overall emotional and spiritual growth. | 3.10 | 1.41 | 1–5 |

| Has helped me become more aware of the love and support available from other people. | 4.07 | 1.05 | 1–5 |

| Has helped me realize who my real friends are. | 3.82 | 1.19 | 1–5 |

| Has helped me become more focused on priorities with a deeper sense of purpose in life. | 3.48 | 1.22 | 1–5 |

| Has helped me become a stronger person, more able to cope effectively with future life challenges. | 3.36 | 1.26 | 1–5 |

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [45]. Participants responded to items based on how they felt within the past month. Higher scores indicated more severe depressive symptoms. This scale has been utilized to assess depressive symptoms in gynecological cancer patients in prior studies [35, 44]. Internal consistency was .84. We used the following cutoff ranges to describe depressive symptom severity in our sample: none or minimal depression is < 10, mild to moderate depression is 10–18, moderate to severe depression is 19–29, and severe depression is 30–63 [46].

Acceptance of cancer.

The acceptance subscale of the COPE [9] assesses use of four strategies (e.g., “I accept that this has happened and it can’t be changed,” and “I learn to live with it”). Participants were asked how often they used coping strategies within the past month (1 = did not do this, 4 = did this a lot). The scale has been used in our prior work with gynecological cancer patients [47]. Internal consistency in the current study was .88.

Acceptance of emotion.

Acceptance of emotion was assessed via the 13-item Acceptance of Emotion Scale [27, 38]. This scale assesses the extent to which individuals are accepting of their emotions in general. Participants were asked to rate how well statements described them (0 = not at all like me, 100 = exactly like me), such as, “Knowing they are ‘not perfect,’ I am comfortable with my feelings as they are,” and “I naturally and easily attend to my feelings.” Higher scores indicate greater emotional acceptance. Although the scale has not been used to study gynecological cancer patients, it has been used in studies of women diagnosed with breast cancer [27, 38, 48]. Internal consistency was .95.

Social support.

Three items from the FACT-G [49] were used to assess friend and family support (“I get emotional support from my family,” “I get support from my friends,” and “My family has accepted my illness.”). Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants reported how true the statements were for them within the past seven days (0 = not at all, 4 = very much). Internal consistency in the current study was .85.

Data analysis

Both descriptive and mediational analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24. Categorical covariates were dichotomized and effect coded. Ethnicity was coded as White, not Hispanic = 1, all others = −1; marital status was coded as married = 1, not married = −1; education was coded as BA degree or higher = 1, all others = −1, employment status was coded 1 if the patient was working either part- or full-time, −1 otherwise, metastatic status was coded as 1 = metastasis, −1 = no metastasis, and cancer type was coded as ovarian cancer = 1, all others = −1. Quantitative medical and demographic covariates included in the analyses were functional impairment, cancer stage, time since diagnosis, and patient age. Selection of demographic and medical factors was based on variables associated with depressive symptoms in prior work [47, 50–54]. A correction for multiple comparisons was not made.

Two multiple mediator analyses [55] were conducted to estimate the total, direct, and indirect effects of the predictor (benefit finding) on the outcome (depression) via three mediators (acceptance coping, acceptance of emotions, and social support). The first analysis included only the predictor, outcome, and mediators, and the second included the predictor, outcome, mediator, as well as the demographic and medical covariates. The multiple mediator approach provides estimates of the extent to which each individual mediator shows indirect effects when controlling for the presence of the other mediators in the model. It also estimates the extent to which the three proposed mediators as a set account for the association between benefit finding and depression. The Preacher and Hayes mediation macro [55] with 5000 bootstrapped samples and bias corrected estimates was used to generate confidence intervals for the overall indirect effect as well as the unique (i.e., partial) indirect effects for each mediator.

Results

Sample characteristics

Demographic and medical characteristics of the sample are in Table 2. Most participants completed at least a college education (61.5%) and were Caucasian (75.9%). About half of participants was diagnosed with Stage III disease (49.4%) and typically diagnosed almost four months prior to participation (M = 3.90, SD = 1.90). More than half of the participants had a primary ovarian cancer diagnosis (65.5%). Most participants reported either no or minimal (40.5%) or mild to moderate (42%) depression [46]. Rates of moderate to severe depression (14.5%) or severe depression (3%) were relatively low.

Table 2.

Demographic and medical characteristics of the study sample

| Variable | n(%) | M(SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 55.32(10.28) | 23–82 | |

| Annual income ($) | 119,719(102,280) | 0–600,000 | |

| Ethnic background | |||

| Caucasian | 132(75.9) | ||

| Non-Caucasian | 41(23.6) | ||

| Missing | 1(0.5) | ||

| Education level | |||

| ≤ high school | 30(17.2) | ||

| Some college, trade, or business school |

37(21.3) | ||

| College graduate or higher | 107(61.5) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 118(67.8) | ||

| Not married | 56(32.2) | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Full time | 41(23.6) | ||

| Part time | 27(15.5) | ||

| On leave | 57(32.8) | ||

| Retired/not employed | 28(16.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 20(11.5) | ||

| Missing | 1(0.5) | ||

| Primary cancer | |||

| Ovarian | 114(65.5) | ||

| Other | 60(34.5) | ||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 3.90(1.90) | 0.93–16.33 | |

| ECOG | |||

| 0 | 116(66.7) | ||

| 1 | 52(29.9) | ||

| Missing | 6(3.4) | ||

| Cancer stage | |||

| I | 25(14.4) | ||

| II | 24(13.8) | ||

| III | 86(49.4) | ||

| IV | 37(21.3) | ||

| Missing | 2(1.1) | ||

| Cancer treatment | |||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 124(71.3) | ||

| Other | 21(12.0) | ||

| Missing | 29(16.7) | ||

| Time since surgery (months) | 3.36(1.17) | .07–14.50 | |

| Functional impairment | 34.03(19.66) | 0–89.28 |

Benefit finding

Descriptive information about benefit finding is in Table 2. The top-rated items were the following: “Has helped me become more aware of the love and support available from other people,” “Has helped me to realize who my real friends are,” “Has brought my family closer together,” and “Has made me realize the importance of planning for my family’s future.” The lowest-rated items were: “Has led me to meet people who have become some of my best friends” and “Has led me to deal better with stress and problems.” We compared the total benefit finding scale score (M = 56.81, SD = 15.37) with other studies using the same scale assessing cancer patients at a time point close to their initial diagnosis. Our sample reported higher benefit finding as compared with Wang et al. [14], who studied early stage breast cancer patients the week after cancer diagnosis (M = 44.95, SD = 7.60; t(576) = 12.8, p < .001) and six weeks after diagnosis (M = 40.84, SD = 6.03, t(576) = 17.94, p < .001). The scores for the our sample were not significantly different than Llewelyn et al. [5] who studied head and neck patients who were evaluated right after diagnosis (M = 59.79, SD = 7.59; t(275) = 1.84, p = .07).

Preliminary Analyses

Table 3 presents the correlations among the quantitative variables. As can be seen in the Table, the associations between depression, benefit finding, and the mediators were generally moderate in size, with the exception of the association between acceptance of emotion and benefit finding, which had a large correlation of r = .54. The only covariate that was consistently associated with the model variables was functional impairment. Patients who reported greater impairment also reported greater depression, less acceptance coping, and lower social support. Age was modestly associated with depression such that older patients reported less depression.

Table 3.

Correlations between depression, benefit finding, the mediators, and the quantitative covariates

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | - | ||||||||

| Benefit finding | −.25** | - | |||||||

| Acceptance coping | −.35** | .36** | - | ||||||

| Acceptance of emotion | −.39** | .54** | .40** | - | |||||

| Social support | −.31 | .38** | .22** | .29** | - | ||||

| Functional Impairment | .63** | −.13 | −.22** | −.15* | −.10 | - | |||

| Stage | −.03 | .05 | −.00 | −.04 | .13 | .15 | - | ||

| Time since Dx | −.06 | −.02 | .04 | .03 | .00 | .03 | .02 | - | |

| Age | −.19* | −.01 | .05 | .14 | −.03 | .01 | .16* | .09 | - |

| M | 13.77 | 3.34 | 13.01 | 5.82 | 9.92 | 34.03 | 2.78 | 116.94 | 55.32 |

| SD | 7.63 | .90 | 3.22 | 2.44 | 2.44 | 19.66 | .95 | 56.92 | 10.28 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

To determine whether the categorical covariates were associated with the key model variables, we conducted independent group t-tests, treating the categorical variable as the predictor and depression, benefit finding, and the mediators as outcomes. Only one significant effect emerged for metastatic status, such that patients with metastasis reported significantly higher social support (M = 10.45, SD = 1.91) than patients without metastasis (M = 9.40, SD = 2.77; t(170) = 2.88, p = .004). No differences emerged for cancer type.

In terms of the demographic covariates, White/not Hispanic patients reported significantly higher depression (White/not Hispanic M = 14.44, SD = 7.44, Other ethnicity/race M = 11.66, SD = 7.93; t(171) = 2.07, p = .040), significantly lower benefit finding (White/not Hispanic M = 3.24, SD = .89, Other ethnicity/race M = 3.66, SD = .88; t(172) = 2.68, p = .008), and acceptance of emotion (White/not Hispanic M = 5.61, SD = 2.35, Other ethnicity/race M = 6.51, SD = 2.62; t(172) = 2.11, p = .036) relative to members of other racial/ethnic groups. Patients who were employed either full or part-time reported significantly lower depression (M = 11.48, SD = 6.06) relative to patients who were not employed (M = 15.21, SD = 8.22; t(170) = 3.20, p = .002). Married patients reported significantly higher social support (M = 10.21, SD = 2.04) as compared to unmarried patients (M = 9.32, SD = 3.03; t(171) = 2.30, p = .023). Finally, no differences were found associated with education level.

Mediation Analysis

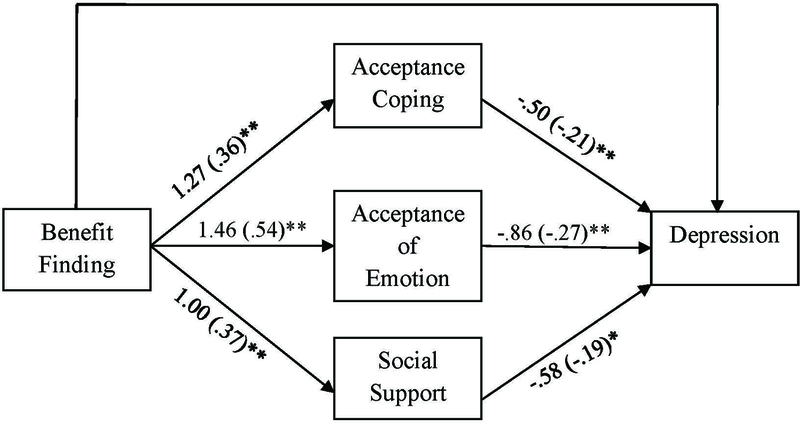

Figure 2 presents the unstandardized and standardized path coefficients for the total effect of benefit finding on depression (i.e., path c, β = −.26, b = −2.15, p < .001), as well as all of the direct effects of the predictor (i.e., path c’, β = .04, b = .31, p = .673) and the mediators (i.e., b paths) on depression in the mediational model that does not include the covariates. The total indirect effect of benefit finding on depression was β = −.29, b = −2.46, SE = .50, 95% CI:−3.67 to −1.50. Because none of the 95% CIs contained zero, each of the three mediators contributed significantly to this total indirect effect. Specifically, the partial indirect effect of benefit finding on depression via acceptance coping was β = −.07, b = −.63, SE = .26, 95% CI −1.24 to −.22, the partial indirect effect via acceptance of emotion was β = −.15, b = −1.25, SE = .41, 95% CI −2.16 to −.54, and the partial indirect effect via social support was β = −.07, b = −.58, SE = .26, 95% CI −1.27 to −.10. These path coefficients indicate that acceptance of emotion accounted for about half of the total indirect effect of benefit finding on depression, and the other two mediators each account for approximately a fourth of that total indirect effect. In sum, these results suggest that each of the proposed mediators plays a role in the association between benefit finding and depression, and that acceptance of emotion shows the strongest partial effect, controlling for the other two mediators.

Fig. 2.

Results for the multiple mediation model of the relationship between benefit finding, depression, and three mediators (acceptance of emotion, acceptance of cancer, social support) excluding covariates. Total effect without mediators (path c) b = −2.16, β = −.26, p = .001 Direct effect with mediators (path c’) b =.31, β = .04, p = .673.

As noted, we conducted a second mediational analysis that controlled for the effects of medical and demographic covariates on depression. The full regression model results with the standardized and unstandardized partial regression coefficients are presented in Table 3. In this case, the total effect of benefit finding on depression (path c), controlling for the covariates was β = −.17, b = −1.45, SE = .51, t = 2.87, p = .005, and as shown in the Table, the direct effect (i.e., path c’) was β = .04, b = .37, SE = .59, t = 0.63, p = .531. The total indirect effect of benefit finding on depression, controlling for the covariates was β = −.22, b = −1.82, SE = .43, 95% CI −2.71 to −1.03. As was the case in the model that excluded the covariates, in this model, each of the mediators contributed significantly to the total indirect effect, with acceptance of emotion accounting for approximately half of the mediated effect. Controlling for the covariates, the partial indirect effect of benefit finding on depression via acceptance coping was β = −.05, b = −.42, SE = .22, 95% CI −.96 to −.07, the partial indirect effect via acceptance of emotion was β = −.10, b = −.87, SE = .33, 95% CI −1.60 to −.30, and the partial indirect effect via social support was β = −.06, b = −.53, SE = .25, 95% CI −1.12 to −.09.

Partitioning the variance in the model showed the following results: The ten covariates together accounted for 47% of the variance in depression. Above and beyond these covariates, benefit finding accounted for 2.6% of the variance in depression. Above and beyond the covariates and benefit finding, the set of mediators - emotional acceptance, acceptance of cancer, and support - accounted for 7.9% of the variance in depression. Breaking these associations down, above and beyond the ten covariates, benefit finding, and the other two mediators, acceptance of cancer accounted for 1.4% of the variance in depression. Emotional acceptance accounted for 2.3% of the variance in depression and social support accounted for 2.1% of the variance in depression. All of these variances were significant. The entire model with covariates, benefit finding, and the three mediators accounted for 58% of the variance in depression (54% using adjusted R-squared).

Discussion

Little attention has been paid to understanding possible mechanisms for the positive association between benefit finding and psychological adjustment among cancer patients that has been found in a number of studies. In this study, we evaluated the premise that benefit finding is associated with fewer depressive symptoms because it facilitates acceptance of emotions, fosters greater acceptance of cancer, and supportive responses by family and friends. Our findings were consistent with our predictions. In this section, we will discuss these findings in more detail as well as their clinical and theoretical implications.

Acceptance of cancer, emotional acceptance, and supportive responses each contributed to the association between benefit finding and depression, accounting together for almost 8% of the variance in depression over and above the covariates and benefit finding. Thus, all three processes played a role. However, the strongest indirect effect was found for emotional acceptance. Acceptance of emotion accounted for approximately half of the mediated effect. Prior work has found that emotional acceptance is associated with lower distress [27, 28, 30]. This study extends the literature to indicate that benefit finding may be associated with reduced depression because it is related to increases in patients’ willingness to feel positive and negative emotions. Similarly, acceptance of cancer has been consistently associated with less distress [11, 27, 28]. Our study suggests that benefit finding may reduce depression by increasing acceptance of the cancer and further underscores the importance of acceptance coping processes.

The finding that social support was a mediator in the association between benefit finding and depression is intriguing. The majority of the work on benefit finding has been guided by social cognitive theory [56], which hypothesizes that social support functions to enhance one’s ability to cognitively process an event by allowing individuals to cognitively process rather than suppress their thoughts and feelings. In this model, support enhances benefit finding. Our approach to understanding a function of benefit finding was to conceptualize it as a positive reappraisal that fosters positive responses from friends and family. As proposed by Silver and colleagues [57], persons who discuss the positive aspects of a stressful experience solicit more positive evaluations and responses from others.

Theoretical and Clinical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, our findings advance the knowledge base of the social-cognitive processing of difficult life events. Benefit finding may foster social and cognitive processing of cancer. When individuals discuss positive aspects of the cancer experience with others, they are more likely to experience supportive responses and hear new perspectives on their situation. These responses can facilitate other types of processing of the cancer experience [31, 56, 58, 59]. For example, during discussions about the benefits of the cancer experience, family and friends may point out other positive or meaningful aspects of the cancer experience. In addition, empathy and validation from close others improves patients’ comfort with their negative emotional reactions and intrusive thoughts which can reduce avoidance and increase emotional acceptance [59–61]. Our findings suggest that benefit finding facilitates other types of accommodative cognitive processes such as acceptance, which adds to the existing literature on how adaptive cognitive processing may enhance adjustment to difficult life events.

Should these results be replicated in longitudinal studies and with patients diagnosed with other types of cancer, our results have novel clinical implications. First, since benefit finding may reduce depression by fostering patients’ willingness to comfortably experience both positive and negative emotions, therapy approaches that focus on increasing cancer patient’s awareness of and tolerance for positive and negative emotional reactions (e.g., Emotion-focused therapy, Compassion-focused Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) may have stronger effects if they incorporate benefit finding strategies as a way to foster acceptance of patients’ emotional reactions to cancer. Second, benefit finding interventions such as journaling about benefits or expressing aspects of life for which the patient is grateful [21, 62] may benefit from incorporating emotional reactions as a part of the cancer experience for which the patient is grateful. Third, because benefit finding was associated with depressive symptoms via higher social support, intervention approaches that foster benefit finding may prove more efficacious if they incorporate an examination of interactions with family and friends about the cancer experience. For example, adding a component to benefit finding interventions in which patients address how they talk about the cancer experience with close others may enhance benefit finding intervention effects. Balancing sharing of negative and positive impacts may enhance treatment effects on depression. Fourth, acceptance-based cognitive interventions such as mindful meditation [30] may be bolstered if clinicians can link the process of finding benefits in the cancer experience to acceptance.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the understudied target patient population, the examination of demographic and medical correlates of benefit finding and its association with depression, and the novel conceptualization of the role of benefit finding.

There are at least three limitations of this study. First, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the sample characteristics. We had a relatively low acceptance rate (25%). Further, study refusers were older, were less likely to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and had a greater time since diagnosis compared to participants. It is possible that the associations would differ if the acceptance rate was higher. Most of our sample was Caucasian (76%), had at least a 4-year college education (62%), and had an average annual income of over $100,000. Our findings may not be generalizable to patients who are not Caucasian, less educated, and had lower incomes. Our sample consisted of women newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer (66%), and the model may differ if we assessed patients later in the cancer journey as they discover different benefits in cancer experience, or if we studied women diagnosed with other cancers or men diagnosed with cancer.

Second, the survey was relatively lengthy and the measures utilized in this analysis appeared at the beginning and the end of the survey. It is possible that patients felt fatigued by the length of the assessment and may have completed the last scale less carefully. Future investigations should consider randomizing the order of the measures to mitigate measurement error due to cognitive fatigue. Third, as noted previously, we utilized cross-sectional data, which limits causal inferences.

Directions for future research

This study raises a number of questions to address in future work. The first question is whether our cross-sectional findings would be replicated with longitudinal data. A second question is whether alternate models are possible. For example, it is possible that benefit finding mediates the association between acceptance and depression, or that depression leads to lower acceptance and ultimately to less benefit finding. The evaluation of alternative models of causality would also be strengthened by a longitudinal design. A third question is whether we can assess the construct of emotional acceptance better. The measure we used has face validity and has been used in prior research [27, 48]. However, there are other measures that have been developed to assess emotional acceptance. For example, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ; [63]) evaluates emotional acceptance as part of the broader construct of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance.

A fourth question is why benefit finding is associated with supportive responses from friends and family. Assessing family and friend perceptions of how (and whether) the patient shared any benefits she has found in the cancer experience (e.g., feeling more patient, having a sense of purpose in life) or asking whether the family and friends can identify changes in qualities they have seen in the patient (e.g., she seems more patient) may illuminate how benefit finding solicits supportive responses from family and friends. Fifth, future work should examine the role of broader psychological constructs that may underlie many of the variables we studied. For example, there has been an ongoing debate about an overlap between optimism and benefit finding (see [1, 11]). Optimism is considered a personal disposition and an orientation to the world, whereas benefit finding is thought to be a reappraisal of a specific stressor to find positive aspects of that stressor. That is why persons who find benefits in a difficult life experience endorse higher dispositional optimism [11, 64–66]. However, most studies report an association of low magnitude (r = .10, [7,46]; r =.25,[11]). Thus, the literature suggests that benefit finding is a coping strategy related to optimism, but not a personality characteristic itself. Similarly, as we noted above, emotional acceptance may reflect a specific application of skill set associated with psychological flexibility.

Since depressive symptoms are linked with health-related quality of life among cancer patients [18–20], this study highlights the importance of expanding this model to include health-related quality of life outcomes in future research. Although depression and health-related quality of life are strongly associated with one another, they are traditionally considered distinct constructs [67–69]. In addition to exploring the role of acceptance and support as putative mediator, future research may also explore additional social and cognitive processing variables which may act as mediators for a health-related quality of life outcome.

Conclusions

Identifying the benefits from one’s experience with cancer may reduce depression by enhancing acceptance coping and fostering positive responses from one’s social network. Because this study is cross-sectional and evaluated a novel meditational model, we cannot make definitive conclusions about the directions of the relationships in our proposed model. Despite these limitations, our results can inform the development of future psychosocial interventions for cancer survivors by elucidating the mechanisms of benefit finding’s relationship with depression.

Table 4.

Results for the regression model predicting depression as a function of benefit finding, the three mediator variables, the five medical covariates, and the five demographic covariates.

| Type of predictor (& role in mediation model) |

b | β | t(149) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV (c’ path) | |||||

| Benefit Finding | .37 | .04 | .63 | .531 | |

| Mediators (b paths) | |||||

| Acceptance coping | −.34 | −.14 | −2.21 | .028 | |

| Acceptance of emotion | −.62 | −.20 | −2.84 | .005 | |

| Social support | −.53 | −.17 | −2.70 | .008 | |

| Medical covariates | |||||

| Functional impairment | .22 | .55 | 9.32 | .000 | |

| Cancer stage | −.86 | −.10 | −1.64 | .104 | |

| Time since diagnosis | −.01 | −.03 | −.60 | .549 | |

| Metastatic status | .06 | .01 | .13 | .897 | |

| Cancer type | −.52 | −.06 | −1.16 | .250 | |

| Demographic covariates | |||||

| Age | −.14 | −.18 | −3.13 | .002 | |

| Ethnicity | .94 | .10 | 1.84 | .068 | |

| Marital status | −.21 | −.02 | −.45 | .656 | |

| Education | −.05 | −.01 | −.11 | .912 | |

| Employment status | −.41 | −.05 | −.88 | .378 |

Note. Metastatic status is coded 1 = metastasis, −1 = no metastasis; Cancer type is coded 1 = ovarian, −1 = other; Ethnicity is coded 1 = White, not Hispanic, −1 = other; Education is coded 1 = BA degree or more, −1 = less than a BA degree; Employment status is coded 1 = working either full or part-time, −1 = not working

Acknowledgments:

Funding for this study was provided by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 CA085566 awarded to Sharon Manne. We thank project managers Tina Gajda, Sara Worhach, Shira Hichenberg, and Kristen Sorice; assistant project manager Jaime Betancourt; and research study assistants Joanna Crincoli, Katie Darabos, Sloan Harrison, Travis Logan, Glynnis McDonnell, Arielle Schwerd, Marie Plaisime, and Caitlin Scally. We also thank the study participants, their oncologists, and the clinical teams at Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Fox Chase Cancer Center, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson University, Morristown Medical Center, and Cooper University Hospital.

References

- 1.Affleck G and Tennen H, Construing benefits from adversity: adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. J Pers, 1996. 64(4): p. 899–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barskova T and Oesterreich R, Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil, 2009. 31(21): p. 1709–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, and Tomich PL, A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2006. 74(5): p. 797–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordova MJ, et al. , Posttraumatic growth following breast cancer: a controlled comparison study. Health Psychol, 2001. 20(3): p. 176–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llewellyn CD, et al. , Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology, 2013. 22(1): p. 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linley PA and Joseph S, Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J Trauma Stress, 2004. 17(1): p. 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park CL and Folkman S, Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of general psychology, 1997. 1(2): p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu JE, et al. , Posttraumatic growth and psychological distress in Chinese early-stage breast cancer survivors: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology, 2014. 23(4): p. 437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carver CS, You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med, 1997. 4(1): p. 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascoe L and Edvardsson D, Psychometric properties and performance of the 17-item Benefit Finding Scale (BFS) in an outpatient population of men with prostate cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs, 2015. 19(2): p. 169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urcuyo KR, et al. , Finding benefit in breast cancer: Relations with personality, coping, and concurrent well-being. Psychology & Health, 2005. 20(2): p. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen Q, et al. , Mental distress, quality of life and social support in recurrent ovarian cancer patients during active chemotherapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2017. 216: p. 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu L, et al. , Benefit finding trajectories in cancer patients receiving psychological care: Predictors and relations to depressive and anxiety symptoms. Br J Health Psychol, 2018. 23(2): p. 238–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, et al. , Benefit finding predicts depressive and anxious symptoms in women with breast cancer. Quality of Life Research, 2015. 24(11): p. 2681–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fryback DG, et al. , US norms for six generic health-related quality-of-life indexes from the National Health Measurement study. Med Care, 2007. 45(12): p. 1162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenes GA, Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 2007. 9(6): p. 437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grégoire J, et al. , Validation of the Quality of Life in Depression Scale in a population of adult depressive patients aged 60 and above 1994. 3: p. 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz PA, et al. , Breast cancer in older women: quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in the 15 months after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol, 2003. 21(21): p. 4027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reich M, Lesur A, and Perdrizet-Chevallier C, Depression, quality of life and breast cancer: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2008. 110(1): p. 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen FH, et al. , Quality of life and psychological distress are differentially associated with distinct symptom-functional states in terminally ill cancer patients’ last year of life. Psychooncology, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Otto AK, et al. , Effects of a randomized gratitude intervention on death-related fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol, 2016. 35(12): p. 1320–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus RS, & Folkman S, Coping and Adaptation. Tha Handbook of Behavioral Medicine, ed. I.W.D.G. (Ed.). 1984, New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazarus RS, & Folkman S, Stress,appraisal and coping 1984, New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis CG, Nolen-Hoeksema S, and Larson J, Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: two construals of meaning. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1998. 75(2): p. 561–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park CL, Cohen LH, and Murch RL, Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. J Pers, 1996. 64(1): p. 71–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedeschi RG and Calhoun LG, Routes to posttraumatic growth through cognitive processing, in Promoting capabilities to manage posttraumatic stress: Perspectives on resilience 2003, Charles C Thomas Publisher: Springfield, IL, US: p. 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Politi MC, Enright TM, and Weihs KL, The effects of age and emotional acceptance on distress among breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer, 2007. 15(1): p. 73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, and Huggins ME, The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psychooncology, 2002. 11(2): p. 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulpa M, et al. , Anxiety and depression and cognitive coping strategies and health locus of control in patients with ovary and uterus cancer during anticancer therapy. Contemp Oncol (Pozn), 2016. 20(2): p. 171–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feros DL, et al. , Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for improving the lives of cancer patients: a preliminary study. Psychooncology, 2013. 22(2): p. 459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silver R, C.W.C.C., Social Support: An interactional View 1990, Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzer R, et al. , Changes in finding benefit after cancer surgery and the prediction of well-being one year later. Soc Sci Med, 2006. 63(6): p. 1614–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunn J, et al. , Amazon heart: an exploration of the role of challenge events in personal growth after breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol, 2009. 27(1): p. 119–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brand C, Barry L, and Gallagher S, Social support mediates the association between benefit finding and quality of life in caregivers. J Health Psychol, 2016. 21(6): p. 1126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manne SL, et al. , A comparison of two psychological interventions for newly-diagnosed gynecological cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol, 2017. 144(2): p. 354–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oken MM, et al. , Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol, 1982. 5(6): p. 649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karnofsky DA, & Burchenal DAK, The Clinical Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer. valuation of Chemotherapeutic Agents, ed. MacLeod CM. 1949, New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weihs KL, Enright TM, and Simmens SJ, Close relationships and emotional processing predict decreased mortality in women with breast cancer: preliminary evidence. Psychosom Med, 2008. 70(1): p. 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schag CA and Heinrich RL, Development of a comprehensive quality of life measurement tool: CARES. Oncology (Williston Park), 1990. 4(5): p. 135–8;discussion 147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myers SB, et al. , Social-cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecol Oncol, 2013. 128(1): p. 120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antoni MH, et al. , Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol, 2001. 20(1): p. 20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomich PL and Helgeson VS, Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol, 2004. 23(1): p. 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crawford JJ, et al. , Associations between exercise and posttraumatic growth in gynecologic cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer, 2015. 23(3): p. 705–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez BD, et al. , Quality of life trajectories after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer: a theoretically based approach. Support Care Cancer, 2017. 25(2): p. 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck AT and Beamesderfer A, Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry, 1974. 7(0): p. 151–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beck AT, Steer RA, and Ranieri WF, Scale for Suicide Ideation: psychometric properties of a self-report version. J Clin Psychol, 1988. 44(4): p. 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manne SL, et al. , Mediators of a coping and communication-enhancing intervention and a supportive counseling intervention among women diagnosed with gynecological cancers. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2008. 76(6): p. 1034–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed RG, et al. , Emotional acceptance, inflammation, and sickness symptoms across the first two years following breast cancer diagnosis. Brain Behav Immun, 2016. 56: p. 165–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cella DF, et al. , The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol, 1993. 11(3): p. 570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arden-Close E, Gidron Y, and Moss-Morris R, Psychological distress and its correlates in ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology, 2008. 17(11): p. 1061–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mielcarek P, Nowicka-Sauer K, and Kozaka J, Anxiety and depression in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a prospective study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol, 2016. 37(2): p. 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norton TR, et al. , Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: the role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychol, 2005. 24(2): p. 143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ploos van Amstel FK, et al. , Self-reported distress in patients with ovarian cancer: is it related to disease status? Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2015. 25(2): p. 229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wen KY, et al. , Psychosocial correlates of benefit finding in breast cancer survivors in China. J Health Psychol, 2017. 22(13): p. 1731–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preacher KJ and Hayes AF, Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods, 2008. 40(3): p. 879–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lepore SJ A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer, in Psychosocial interventions for cancer 2001, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US: p. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silver RC, C.B.W.C.C., The role of coping in support provision: The self-presentational dilemma of victims of life crises 1990, Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janoff-Bulman R Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma 1992, New York, NY, US: Free Press; xii, 256-xii, 256. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lepore SJ, Ragan JD, and Jones S, Talking facilitates cognitive-emotional processes of adaptation to an acute stressor. J Pers Soc Psychol, 2000. 78(3): p. 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lepore S,R,J, Helgeson V Social constraints moderate the relation between instrusive thoughts and mental health in prostate cancer survivors. J of Social and Clinical Psyhcol, 1998. 17: p. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thoits PA, Social support as coping assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol, 1986. 54(4): p. 416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng ST, et al. , Benefit-finding and effect on caregiver depression: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2017. 85(5): p. 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes SC, et al. , Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 2004. 54(4): p. 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pascoe EC and Edvardsson D, Psychological Characteristics and Traits for Finding Benefit From Prostate Cancer: Correlates and Predictors. Cancer Nurs, 2016. 39(6): p. 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sears SR, Stanton AL, and Danoff-Burg S, The yellow brick road and the emerald city: benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol, 2003. 22(5): p. 487–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Affleck HTG, Finding Benefits in Adversity 1999, New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Angermeyer MC, et al. , Depression and quality of life: results of a follow-up study. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2002. 48(3): p. 189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katschnig H, et al. , Quality of life in depression. European Psychiatry, 1997. 12: p. 116s. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rudolf H and Priebe S, Subjective quality of life in female in-patients with depression: a longitudinal study. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 1999. 45(4): p. 238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]