Abstract

The mechanistic aspects of one-electron oxidation of G-quadruplexes in the basket (Na+ ions) and hybrid (K+ ions) conformations were investigated by transient absorption laser kinetic spectroscopy and HPLC detection of the 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) oxidation product. The photo-induced one-electron abstraction from G-quadruplexes was initiated by sulfate radical anions (SO4•−) derived from the photolysis of persulfate ions by 308 nm excimer laser pulses. In neutral aqueous solutions (pH 7.0), the transient absorbance of neutral guanine radicals, G(−H)• is observed following the complete decay of SO4•− radicals (~10 µs after the actinic laser flash). In both basket and hybrid conformations, the G(−H)• decay is biphasic with one component decaying with a lifetime of ~ 0.1 ms, and the other with a lifetime of 20–30 ms. The fast decay component (~0.1 ms) in G-quadruplexes is correlated with the formation of 8-oxoG lesions. We propose that in G-quadruplexes, G(−H)• radicals retain radical cation character by sharing the N1-proton with the O6-atom of G in the [G•+: G] Hoogsteen base pair; this [G(−H)•: H+G ⇆ G•+: G] leads to the hydration of G•+ radical cation within the millisecond time domain, and is followed by the formation of the 8-oxoG lesions.

Graphical Abstract

One-electron abstraction from G-quadruplexes initiated by sulfate radical anions (SO4•−) derived from the photolysis of persulfate ions (S2O82−) by 308 nm excimer laser pulses, results in the formation of guanine radical intermediates monitored by transient absorption spectroscopy. In G-quadruplexes, neutral guanine radicals [G(−H)•] retain radical cation character. The hydration of these cation radicals within the millisecond time domain leads to the formation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) lesions.

INTRODUCTION

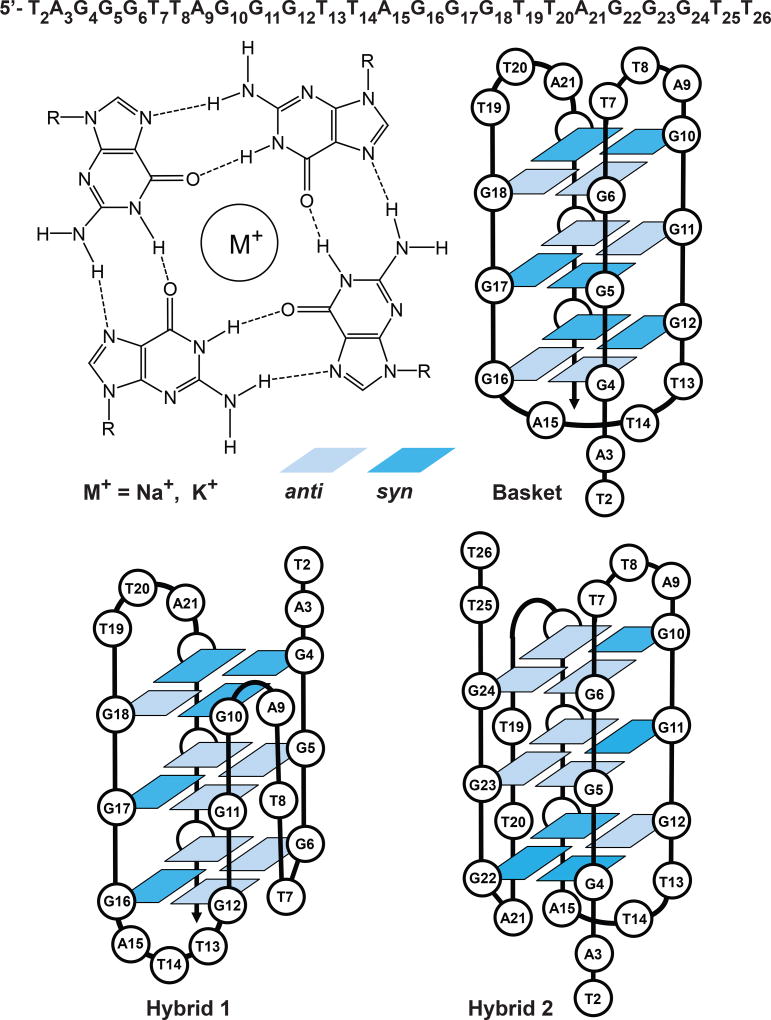

In human cells, the chromosome ends are protected from degradation by telomeres, which consist of multiple repeats of 5’-(TTAGGG)n-3’sequences (1). The first 5–15 kilobase pairs of this sequence is paired with the complementary strand, while the remaining 50–200 nucleotides are single stranded (2). The single stranded part of the telomeric repeat folds into a structure known as the G-quadruplex (3). In this structure, four guanine bases are arranged at the corners of a square forming a Hoogsteen hydrogen-bonded G-tetrad (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of G-tetrads in the basket hybrid 1, and hybrid 2 folds of the 5’-d(TAGGG)(TTAGGG)3TT fragment of human telomeric DNA (38). The bases are numbered sequentially from 2 to 26, and light and dark blue boxes represent anti and syn guanines, respectively.

In the presence of appropriate metal cations three such squares are stacked against one another. The Na+ and K+ cations stabilize the G-quadruplex by being placed in a channel between each pair of G-tetrads. In aqueous solutions, G-quadruplexes form different structures, depend on the nature of the counterions. In the presence of Na+ cations, the basket fold is dominant (4), while in the presence of K+ cations, the hybrid folds are formed (5) (Figure 1).

Telomere lengths have been correlated with aging and mortality (6). Recent studies have shown that telomere shortening is associated with the life-long exposure to oxidative and inflammatory stress (7–9). Guanine bases are particularly susceptible to oxidation (10), most commonly resulting in the formation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG) lesions (11). The latter are genotoxic, since failure of removing 8-oxoG before replication induces G:C → T:A transversion mutations (12, 13). Formation of 8-oxoG can be initiated by the oxidation of guanine bases with hydroxyl (14) and peroxyl (15, 16) radicals, carbonate radical anions, CO3•− (17, 18), one-electron oxidants (19–21), and singlet oxygen (22).

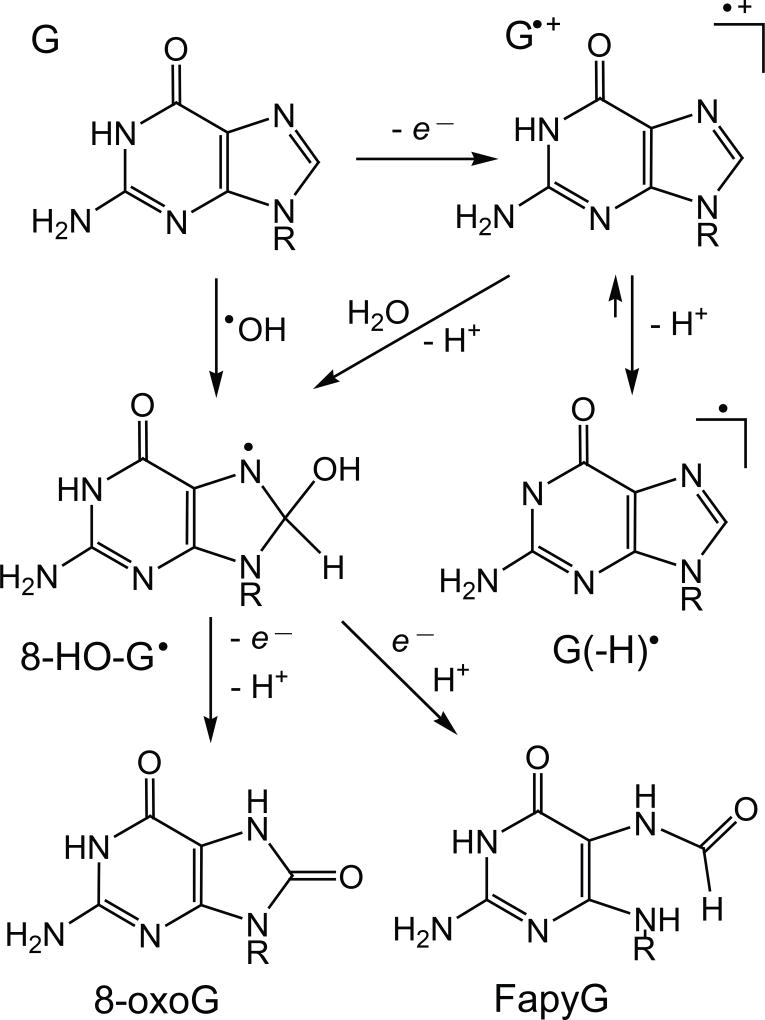

Hydroxyl radicals induce the formation of 8-oxoG within free guanine nucleosides, both single- and double-stranded DNA (14) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of 8-oxoG and FapyG formation initiated by one-electron oxidation or by •OH addition to guanine at C8 in DNA.

Direct addition of •OH radical to C8 of guanine results in formation of the 8-hydroxy-7,8-dihydroguanyl radical (8-HO-G•) (23, 24). The fate of this radical depends on the redox conditions of the solution (23). Molecular oxygen, or other weak oxidants, rapidly oxidize 8-HO-G• to yield the 8-oxodGuo lesions. The competitive decay of 8-HO-G• involves purine ring opening, followed by the one-electron reduction that leads to the formation of 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyG). The latter dominates under reductive conditions (25).

In contrast, formation of 8-oxoG by one-electron oxidants occurs predominantly in double-stranded DNA (19). Guanine radical cations (G•+) derived from electron abstraction from guanine decay by two competitive pathways: (i) hydration with the formation of 8-HO-G• radicals, and (ii) deprotonation with formation of neutral guanine radicals, G(−H)• (26) (Figure 2). Depending on the redox status of the solution, 8-HO-G• radicals are transformed to either 8-oxoG or FapyG (23–25). The G(−H)• radicals can also combine readily with other free radicals to form stable end-products derived from radical addition to either the C8- or C5-sites of the guanine radicals (27, 28). For instance, G(−H)• radicals can combine with nitrogen dioxide radicals (•NO2) to form 8-nitroguanine and 5-guanidino-4-nitroimidazole, and with superoxide radical anions (O2•−) to form 2,5-diamino-4H-imidazolone (Iz) and 2,2,4-triamino-2H-oxazol-5-one (27, 29–31). Furthermore, G(−H)• radicals can combine with CO3•− radicals to form 8-oxoG and 5-carboxaamido-5-formamido-2-iminohydantoin (18, 32).

Kinetic studies of radical intermediates by transient absorption spectroscopy, coupled with the detection of 8-oxodGuo lesions by HPLC methods, allowed us to directly correlate the decay of G(−H)• radicals with 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodGuo) formation induced by the one-electron oxidation of guanine in single- and double-stranded oligonucleotides under oxidative conditions (33). The results of these studies suggest that in double-stranded DNA, the deprotonation of G•+ radicals occurs via a shift of the N1-proton to the N3-site of cytosine. The G(−H)• radicals in the Watson-Crick base pair retain some cationic character due to the equilibrium between G(−H)• and G•+ (Figure 2). The G•+ radicals decay on timescales of milliseconds by two competitive pathways. The first involves the hydration that results in the formation of 8-oxodGuo, and the second involves the release of the N1 protons into the bulk solution. These reactions are characteristic of the solvent-protected environment in the G-quadruplexes, since in single-stranded DNA the lifetime of the G(−H)• radical is of the order of seconds (33).

Oxidation of G-quadruplexes has been studied in hybrid (K+) and basket (Na+) folds (34, 35). Formation of 8-oxoG has been detected using four oxidant systems consisting of riboflavin photosensitization (one-electron oxidation), carbonate radical generation, singlet oxygen, and the copper Fenton-like reaction for generation of •OH radicals (34–37). However, the kinetic characteristics of guanine radicals in G-quadruplexes remain unknown.

The objectives of this work were to directly monitor the kinetics of decay of G•+ and G(−H)• radicals in different folds (basket and hybrids) of G-quadruplexes using transient absorption spectroscopy, and to measure, in parallel, the formation of 8-oxodGuo using HPLC methods of analysis. In these experiments we used 5’-d[TAGGG(TTAGGG)3TT] fragment 1 of the human telomeric DNA (Figure 1). This sequence was folded in the presence of either Na+ or K+ cations to generate the basket or hybrid forms, respectively (38). The control DNA duplex was prepared by annealing sequences 1 and 2; the latter is a natural complementary strand 5'-d[AA(CCCTAA)3CCCTA] for strand 1. This novel approach allowed us, for the first time, to directly correlate the kinetics of guanine radical decay with 8-oxodGuo formation induced by one-electron oxidation of guanine in basket and hybrid folds of G-quadruplexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

All chemicals (analytical grade) were used as received. The oligonucleotides 1 and 2 were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). All oligonucleotides were purified and desalted using reversed-phase HPLC. The integrity of the oligonucleotides was confirmed by MALDI-TOF/MS analysis. Basket and hybrid forms of G-quadruplexes were prepared by dissolving sequence 1 in 20 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) containing 60 mM Na2SO4 or 60 mM K2SO4, respectively. The double-stranded form was prepared by annealing 1:1 mixtures of sequences 1 and 2. Consequently, the samples were heated to 90 °C in a water bath and left to cool slowly overnight.

UV absorbance vs temperature melting curves

UV absorbances of G-quadruplexes or duplexes were monitored at 295 nm or 260 nm, respectively, as a function of increasing temperature from ~ 15 to 70 – 80 °C under standard conditions in 20 mM phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.0, 60 mM Na2SO4 or 60 mM K2SO4, and 20 µM DNA concentrations. The melting temperature (TM) was defined as the temperature at which 50% of G-quadruplex or duplex were dissociated.

Laser flash photolysis

Kinetics of the radical intermediates were monitored directly using a fully-computerized kinetic spectrometer system (~7 ns response time) described elsewhere (32, 33). Briefly, an individual single laser pulse selected by an electromagnetic shutter from a train of 308 nm XeCl excimer laser pulses (~12 ns, 60 mJ/pulse/cm2, 1 Hz) was directed through a rectangular aperture (0.3×1.0 cm) into an 80 µL sample solution in a 0.2×1.0 cm quartz cell. The transient absorbance was probed along a 1 cm optical path by a light beam (75 W xenon arc lamp) oriented perpendicular to the laser beam. The signal was detected with a Hamamtsu 928 photomultiplier tube and recorded by a Tektronix TDS 5052 oscilloscope operating in its high resolution mode that provides a satisfactory signal/noise ratio after a single laser pulse. The rate constants were determined by least squares fits of the appropriate kinetic equations to the experimentally measured transient absorption profiles as described earlier (33, 32). The values reported are averages of five independent measurements.

Quantitation of 8-oxodGuo lesions

The 80 µL air-equilibrated samples (100 µM G-quadruplex or duplex, 20 mM Na2S2O8 in 20 mM phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.0 containing 40 mM Na2SO4 or 60 mM K2SO4) were exposed to a pre-determined number of 308 nm XeCl excimer laser pulses. The irradiated oligonucleotides were placed on ice, washed 3 times with 400 µL of cold water using Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filters (3 kDa MWCO), split into several aliquots containing ~60 µg DNA, and dried under vacuum. The DNA samples (~60 µg) were digested with nuclease P1 (2 units) in 40 mL of 30 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2) containing 0.1 mM ZnCl2 and 3 mM deferoxamine for 3 h at 37 °C; following digestion, 4 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 8.2) containing 100 mM MgCl2 were added and the samples were incubated with 2 units of alkaline phosphatase and 0.04 units of snake venom phosphodiesterase for 2 h at 37 °C. The digestion mixtures were passed through Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filters (10 kDa MWCO) to remove the enzymes. The 2’-deoxyribonucleosides were separated by a reversed-phase HPLC column using a 0 – 24 % linear gradient of acetonitrile in 20 mM ammonium acetate for 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The amounts of 8-oxodGuo were quantified by integration of the chromatograms monitored at 300 nm using for calibration an authentic standard of 8-oxodGuo.

RESULTS

Overview

The 5’-d[TAGGG(TTAGGG)3TT] sequence 1, which is the 25 nt fragment of the human telomeric DNA easily folds in aqueous solutions containing cations to form either basket (Na+) or hybrid 1 and 2 (K+) conformations of G-quadruplexes (38) shown in Figure 1. Formation of higher order DNA structures (e.g., duplexes, triplexes or quadruplexes) can be easily detected employing DNA melting techniques (39). The melting of DNA duplexes is usually observed as an increase in absorbance at 260 nm due to a transition from double- to the single-stranded form. In contrast, DNA quadruplexes show only small changes near the absorption maximum of 260 nm (40). However, the melting of G-quadruplexes can be detected at 295 nm, at which transition to single-stranded form is associated with a relatively large decrease in absorbance (40, 41). The results of melting experiments obtained in this work are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermal melting points of G-quadruplexes formed by the spontaneous folding of 5’-d[TAGGG(TTAGGG)3TT] sequence 1 in solution. The duplexes were prepared by annealing sequence 1 with its natural complementary sequence 2. Melting curves were recorded at 260 nm (duplex) or 295 nm (G-quadruplex) in 20 mM phosphate buffer solution containing 20 µM DNA and 60 mM Na2SO4 or 60 mM K2SO4.

| Conformation | Cation | TM, °C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G-quadruplex | Basket | Na+ | 48.7±0.5 |

| Hybrid | K+ | 60.3±0.5 | |

| Duplex | Double helix | Na+ | 67.6±0.5 |

| Double helix | K+ | 67.3±0.5 |

The value of TM in the presence of K+ cations is greater than in the presence of Na+ ions, thus demonstrating that the hybrid conformations of G-quadruplexes are more stable than the basket conformation in agreement with the literature data (34, 40, 41). In turn, the values of TM were the same within experimental error in the case of double-stranded DNA (42). Therefore, we investigated the oxidation of G-quadruplexes and duplexes at 25 °C that is significantly lower than the melting temperatures (Table 1).

The one-electron oxidation of G-quadruplexes was induced by the photo-induced generation of sulfate radicals, SO4•− a method that has been widely used to initiate the one-electron oxidation of DNA (43–46). In these experiments intense nanosecond 308 nm XeCl excimer laser pulses (~12 ns width) were used to induce the selective photodissociation of peroxodisulfate anions, S2O82− to SO4•− radicals:

| (1) |

The SO4•− radicals are formed with a high quantum yield (~0.55) (47) rapidly oxidize single- and double-stranded DNA by one-electron oxidation mechanism (33, 32, 43–46). The holes thus injected into the DNA by electron abstraction rapidly localize on the guanine bases, and the reaction kinetics can be monitored by the decay of SO4•− radicals at 445 nm (48) and the formation of guanine radicals with a transient absorption maximum at 312 nm (33, 32, 43–46).

Kinetics of guanine radicals in G-quadruplexes

In 50 µM solutions of G-quadruplexes, the lifetime of SO4•− radicals is shortened from ~20 µs in the absence of DNA to ~ 2.5 µs, and the decay of the SO4•− absorption band at 445 nm is well correlated with the growth of new absorbance bands due to guanine radicals in the 300 – 750 nm spectral range as shown by the following equation:

| (2) |

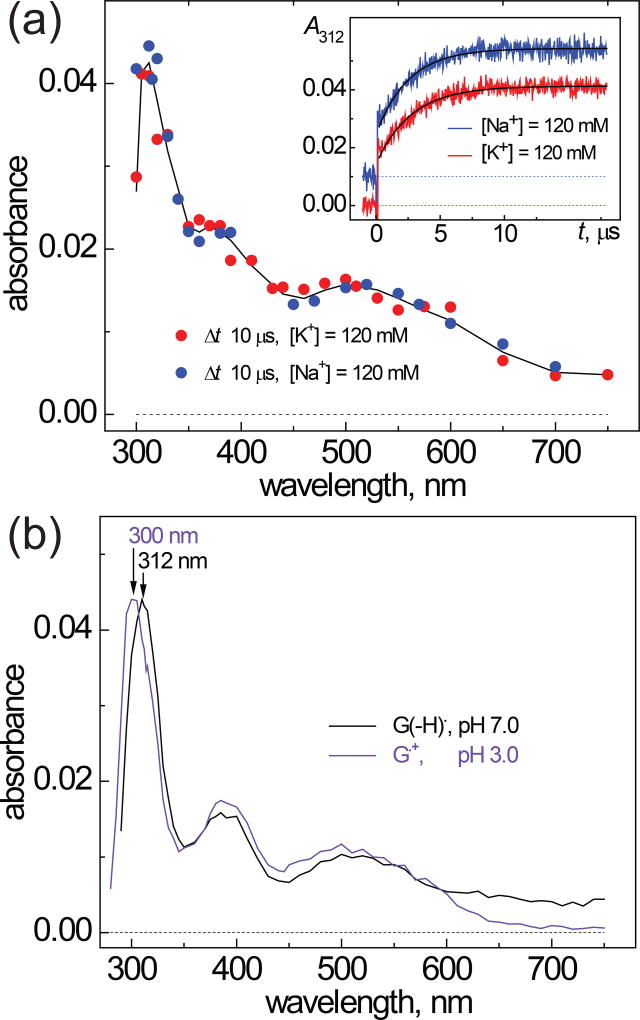

The inset in Figure 3 shows that the rise of the characteristic narrow transient absorption band of guanine radicals at 312 nm occurs with similar rates in both Na+ and K+ solutions.

Figure 3.

(a) Transient absorption spectra recorded after a nanosecond single 308 nm XeCl laser pulse excitation of samples containing 50 µM G-quadruplex 1, 25 mM Na2S2O8 (or K2S2O8) and 35 mM Na2SO4 (or K2SO4) in air-equilibrated 20 mM phosphate buffer solutions, pH 7.0. The inset in Figure 3A shows the transient kinetic traces at 312 nm that are attributed to the formation of guanine radicals in G-quadruplexes in the presence of Na+ (blue) and K+ (red) cations. The single exponential fits to the experimental data points are shown by black lines were obtained using the first-order rate constants, 4.0×105 s−1 (Na+) and 3.6×105 s−1 (K+). (b) Bench-mark transient absorption spectra of neutral guanine radicals, G(−H)•, and guanine radical cations, G•+, recorded after a single nanosecond 308 nm XeCl laser pulse excitation of samples containing 200 µM 2’-deoxyguanosine, 20 mM Na2S2O8 in air-equilibrated 20 mM phosphate buffer solutions, pH 7.0.

The rate constants of one-electron oxidation of G-quadruplexes (k2) were obtained from the best least-squares fits of the appropriate kinetic equations to the transient absorption profiles of the formation of G(−H)• radicals at 312 nm (33, 32, 43–46). The values of k2 are (7.2±0.7)×109 M−1s−1 and (6.4±0.6)×109 M−1s−1 in Na+ and K+ solutions, respectively. The oxidation of DNA duplexes is also very fast and occurs with the rate constant k2 = (8.9±0.9)×109 (33, 32). It is not surprising that the oxidation rates do not depend on G-quadruplex conformation because the reaction rates are controlled by the diffusion of the reactants.

The transient absorption spectrum recorded after complete decay of SO4•− radicals (at Δt = 10 µs) in the solutions of G-quadruplexes is depicted in Figure 3A. The experimental data points recorded in the presence of Na+ (blue) and K+ (red) are grouped close to the spectrum of the radical intermediate generated by SO4•− radicals (black line) which is characterized by a narrow absorption band at 312 nm and two less intense bands near 390 and 510 nm. The bench-mark spectra of the neutral radical, G(−H)• and guanine radical cation, G•+, prepared by one-electron oxidation of 2’-deoxyguanone by SO4•− radicals are shown in Figure 3B. The spectrum of the G•+ radical cation (violet) differs from the spectrum of G(−H)• (black). The narrow absorption band is shifted from 312 nm for G(−H)• to 300 nm for G•+. Moreover, the G•+ radicals have no absorption at λ > 650 nm, whereas a weak absorption of G(−H)• radicals can be detected up to 750 nm (33, 32, 43–46). Thus, the comparison of the spectra of the radical intermediates detected in the solutions of G-quadruplexes with the bench-mark spectra of guanine radicals, demonstrate that the neutral guanine radicals dominate in the transient absorbance of the G-quadruplexes. Recently, the predominance of G(−H)• absorbance has also been observed in the µs transient absorption spectra of the DNA duplexes (33). Collectively, these laser flash photolysis experiments demonstrate that the one-electron abstraction from guanine by SO4•− radicals initiate an extremely rapid reorganization of the local hydrogen bonding network in both G-quadruplex and DNA duplex structures, and thus the G(−H)• absorption spectrum dominates the µs transient absorption spectra of these intermediates.

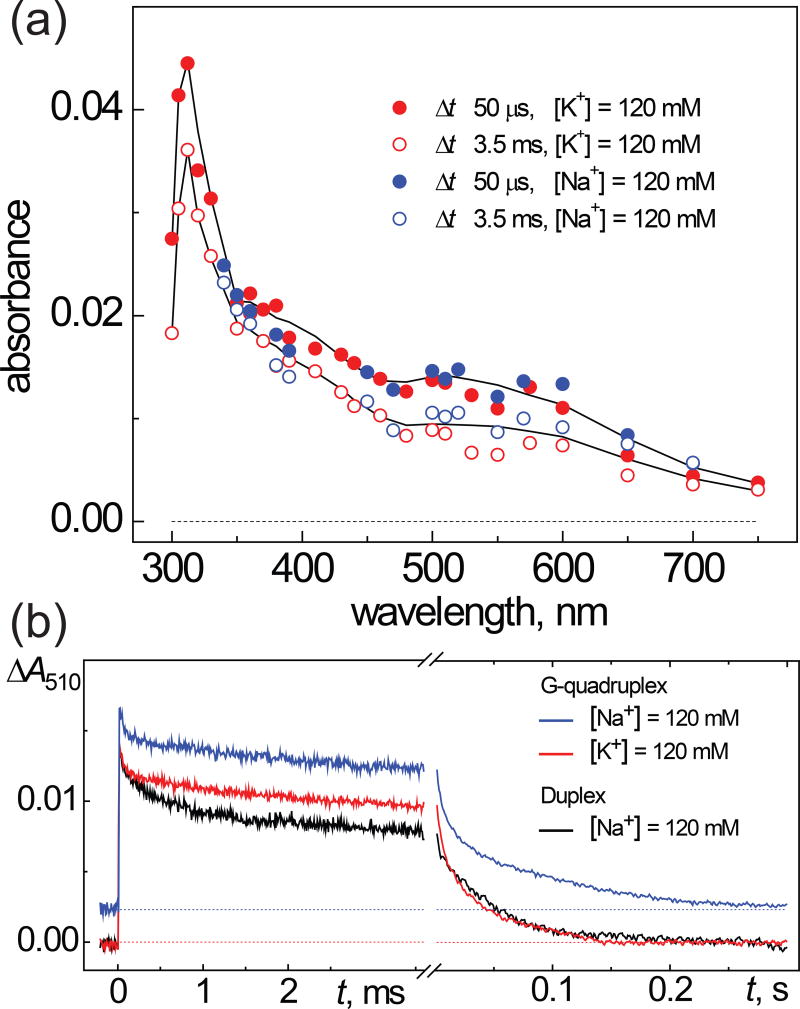

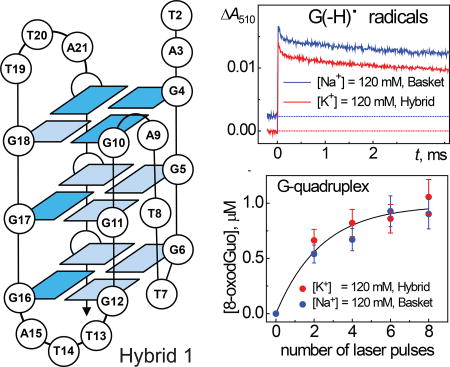

The kinetics of G(−H)• radical decay in G-quadruplexes are heterogeneous and occur in the millisecond and ~one-second time domains (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Transient absorption spectra recorded after a nanosecond single 308 nm XeCl laser pulse excitation of samples containing 50 µM G-quadruplex 1, 25 mM Na2S2O8 (or K2S2O8) and 35 mM Na2SO4 (or K2SO4) in air-equilibrated 20 mM phosphate buffer solutions, pH 7.0. (b) The transient kinetic traces at 510 nm are attributed to the decay of G(−H)• radicals in G-quadruplex solutions containing Na+ (blue) and K+ cations (red) and B-form DNA duplex containing Na+ (black).

The decay of the G(−H)• absorbance occurs with the characteristic decay time of ~0.1 ms and is associated with 25–30% decrease of the signal amplitude in the 310–750 nm spectral range (Figure 4A). Furthermore, the transient absorption spectrum observed at the 3.5 ms time point, displays all of the spectral features of the G(−H)• radicals. The parameters of this fast ms kinetic component (characteristic time and signal amplitude) are practically the same in Na+ (blue) and K+ (red) solutions (Figure 4B). This figure shows that in the case of G-quadruplexes in the 3.0 – 3.5 ms time interval, the amplitude of the G(−H)• signals is reduced to 70–75% of the maximum signal amplitude. In contrast, the decay of G(−H)• radicals in the case of B-form DNA duplexes is more pronounced and only 50–55% of the original radicals survive. Beyond 3.5 ms time point, the decay of the radicals is much slower on time scales of ~0.02 – 0.03 s (Figure 4B). Similar decay kinetics are observed in other B-form DNA duplexes and calf thymus DNA (33). In contrast, the ms kinetic component is not observed in single-stranded DNA and the G(−H)• radicals decay in the one-second time window (33). In the following section we show that the ms kinetic component in the kinetics of G(−H)• radical decay is correlated with the formation of 8-oxodGuo lesions.

Yields of 8-oxodGuo lesions in G-quadruplexes

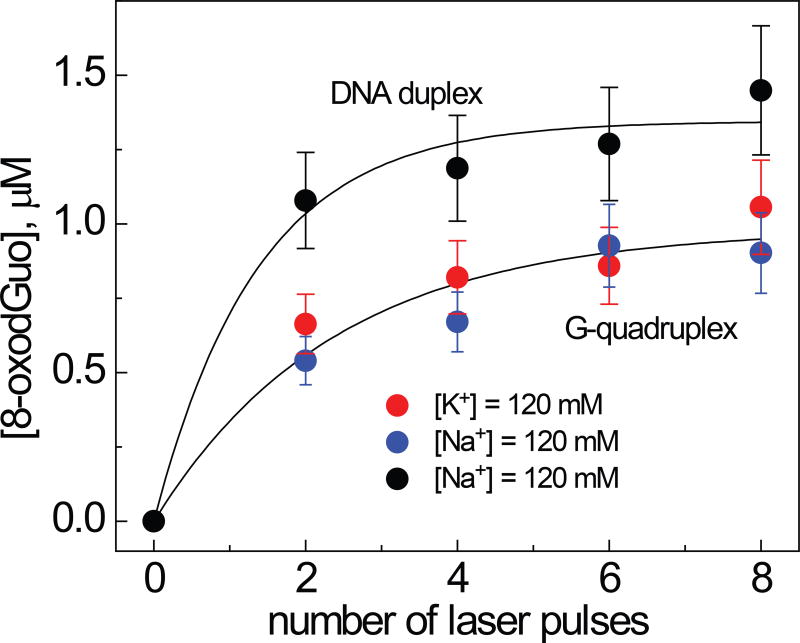

The samples containing 100 µM G-quadruplexes constructed from sequence 1, 20 mM Na2S2O8 (or K2S2O8) and 40 mM Na2SO4 (or K2SO4) in air-equilibrated 20 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.00 were irradiated with defined numbers of successive 308 nm XeCl excimer laser pulses. To provide a complete decay of the radical intermediates, the laser frequency was reduced to 0.1 Hz using a computer-controlled shutter. In these experiments, the concentration of G(−H)• radicals calculated from the transient absorbance detected after a single laser shot was equal to ~ 5 µM per laser pulse. After complete enzymatic digestion to the nucleoside level, the 8-oxodGuo lesions were quantified by reversed-phase HPLC. The yields of 8-oxodGuo lesions as a function of the number of laser pulses are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Dependence of the yields of 8-oxodGuo lesions in G-quadruplexes and B-form DNA duplexes on the number of successive 308 nm laser pulses. The 8-oxodGuo yields were estimated by integrating the areas under the bands of 8-oxodGuo in the HPLC elution profiles recorded at 300 nm.

Increasing the number of laser pulses induced a monotonic rise in the concentrations of the 8-oxoGuo lesions formed in response to generation of G(−H)• radicals. In G-quadruplexes, the concentrations of 8-oxodGuo lesions detected after the first two laser pulses was ~0.3 µM per laser pulse; the yield was only 6% of the amount of G(−H)• radicals generated by a single laser pulse. The 8-oxodGuo concentrations are practically the same in Na+ (blue) and K+ (red) solutions (Figure 5) and hence do not depend on conformation of G-quadruplex (basket or hybrid). In duplex 1, the initial 8-oxodGuo concentrations are by factor of ~2 greater than in G-quadruplexes and equal to ~ 0.6 µM per laser pulse.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we explored the kinetics of the radical intermediates initiated by one-electron oxidation of G-quadruplexes with SO4•− radicals followed by formation of 8-oxodGuo lesions. The SO4•− radical is a very strong one-electron oxidant that unselectively oxidizes all four natural nucleic acid bases (A, G, C and T) (49, 50). Although, all four nucleobases can be oxidized by SO4•− radicals with rate constants that are close to diffusion controlled rates (49), the primary damage to double-stranded DNA is localized at guanine-sites (33, 45, 46). Guanine is the most easily oxidizable nucleobase among the four natural DNA bases (10, 51) and following the one-electron oxidation of any of the four DNA bases in double-stranded DNA, the ‘hole’ is ultimately localized on guanines by hole-hopping mechanisms over long distances (52–57). Here, we found that the one-electron oxidation of G-quadruplexes by SO4•− radicals occurs with rate constants that are close to diffusion controlled rates followed by extremely fast localization of the ‘holes’ on guanine bases (Figure 3). In our 25 nt fragment of the human telomere sequence four 5’-GGG triplets are linked by 5’-TTA loops containing only 3 nucleotides and the distance from any randomly injected hole to the closest G-site does not exceed one base (Figure 1). This is sufficient to provide high yields of guanine radicals per SO4•− oxidant (Figure 3A) in both basket (Na+) and hybrid (K+) conformations of G-quadruplexes (Figure 1). The predominant damage of guanine in G-quadruplexes has been also confirmed by gel electrophoresis methods employing riboflavin photosensitization and carbonate radicals as one-electron oxidants (34–37).

The primary product of one-electron abstraction from guanine is G•+ radical cation, which is an acid with pKa of 3.9 (43, 23). Extensive ESR studies in aqueous solutions (58, 59) and in glassy media at low temperatures (60–62) have shown that in free nucleosides and single-stranded DNA, deprotonation of G•+ occurs via escape of the proton from N1-G•+ to the surrounding water to form the G(N1-H)• radical (58–62). In higher order DNA structures (DNA duplexes and G-quadruplexes), the N1 proton of G is hydrogen bonded to either N3 of C in the GC Watson-Crick base pair of DNA duplex or O6 of G in the GG Hoogsteen base of the G-tetrad (Figure 1). Our major hypothesis is that electron abstraction from guanine induces a prompt reorganization of the hydrogen bonding network occurring as a result of a shift of the N1 proton from G in both Watson-Crick and Hoogsteen base pairs. These fast shifts of the N1 protons explain the predominance of G(−H)• absorption in the µs transient absorption spectra of both G-quadruplexes (Figure 3A) and the DNA duplexes (33). Trapping of the N1 protons in DNA duplexes and G-quadruplexes favors the C8 reaction of guanine radicals with water to form 8-HO-G• radicals (Figure 2). The latter are readily oxidized by weak oxidants (e.g., oxygen) that result in the formation of 8-oxoG lesions (23, 24). The Escape of the N1 protons to the bulk solution competes with the C8 hydration and thus the 8-oxoG yields are decreased.

The C8 hydration and N1 proton escape kinetics manifested themselves as a decay of G(−H)• absorbance in the ms time domain observed in G-quadruplexes (Figure 4) and in DNA duplexes as reported previously (33). In single-stranded DNA, the deprotonation of G•+ is dominant, the kinetics of G(−H)• decay become monophasic and occur within the ~one-second time scale (33). Oxidation of 8-HO-G• radicals by oxygen with formation of 8-oxoG and superoxide radicals is extremely fast (rate constant of 4×109 M−1s−1 (23, 24)) and follows the hydration kinetics. Indeed, in air-equilibrated aqueous solutions ([O2] ≈ 0.26 mM) this reaction occurs in a not-rate determining step, because the lifetimes of 8-HO-G• are in the range of ~1 µs and much shorter than the lifetimes of the ms components (Figure 4B). The O2•− radicals derived from the reduction of oxygen by 8-HO-G• radicals can rapidly combine with G(−H)• radicals with the formation of imidazolone lesions (27, 29–31). Our laser flash photolysis experiments showed that the rate constant of reaction of O2•− with G(−H)•, site-specifically positioned in the DNA duplex is 4.7×108 M−1s−1 (27, 29–31). In typical laser flash photolysis experiments, the combination of G(−H)• and O2•− occurs on characteristic time scales of 0.3 – 0.5 ms and contributes to the observed decay of G(−H)• (the ms component in Figure 4B). Thus, the formation of one 8-oxoG molecule correlates with the decay of two G(−H)• radicals within the ms time domain. The first radical is hydrated with the formation of 8-HO-G• (rate-determining step), and the second rapidly combines with O2•− derived from the reduction of O2 by 8-HO-G•.

In the experiments shown (Figure 5), the concentrations of G(−H)• radicals generated by a single laser pulse (~ 5 µM/pulse) were ~20-fold lower than the concentrations of DNA molecules (~100 µM). These so-called "single-hit" conditions exclude the occurrence of sequential one-electron oxidation events at a particular guanine site that would give rise to product formation by the further oxidation of 8-oxoG lesions, such as 5-guanidinohydantoin and spiroiminodihydantoin, as reported by Fleming, Burrows and co-workers (34, 35). Thus, the 8-oxodG yields detected after first 1 – 2 laser flashes correlate with efficiencies of C8 hydration, which compete with the N1 proton escape. According to this concept the C8 hydration in DNA duplex is more efficient in G-quadruplexes because the 8-oxodG yields per single laser flash is greater by factor of 2 greater than in G-quadruplexes. In agreement with this mechanism, the ms components of the G(−H)• decay are associated with C8 hydration in G quadruplexes and in B-form DNA duplexes (Figure 4B) that are correlated with the 8-oxoG concentrations formed per laser pulse (Figure 5). In contrast, the ms component becomes negligible in single-stranded DNA which correlates with the ~ 7-fold lower drop 8-oxoG concentration/laser pulse relative to double-stranded DNA (33). Figure 5 shows that the concentrations of 8-oxoG per laser pulse decrease with an increasing number of laser pulses and, after the 4th laser pulse, attain a plateau. This can be an indication that the laser excitation generates oxidants, which lead to the oxidation of 8-oxoG when its concentration attains a ~1 µM level. The primary oxidant generated by laser excitation is the SO4•− radical that rapidly oxidizes both G and 8-oxoG with rate constants close to the diffusion controlled values (33, 32). Since the concentration of G-quadruplex molecules (100 µM) is greater by a factor of 100 than concentration of G-quadruplex molecules with 8-oxoG lesions (1 µM), the contribution of this pathway to the degradation of 8-oxoG will be negligible. Another potential oxidant is the G(−H)• radical, a powerful one-electron oxidant that rapidly oxidizes 8-oxoG (44). Our laser flash photolysis experiments showed that the rate constant of the bimolecular reaction between G(−H)• and 8-oxoG site-specifically positioned in the different DNA duplexes, is 2.7×106 M−1s−1 (31). The characteristic decay times for the decay of 8-oxoG via reaction with G(−H)• radicals generated at ~5 µM levels per laser pulse, are in the range of 60–100 ms, and consumption of G(−H)• in this reaction can contribute to the second component of the decay of G(−H)• (Figure 4B). Other pathways of 8-oxoG decay can involve unspecified reactions with peroxides and secondary oxyl radicals that arise from the trapping of alkyl radicals by oxygen formed in side reactions of SO4•− radicals with DNA (63, 64).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health and Sciences Grant R01 ES-027059. Components of this work were conducted in the Shared Instrumentation Facility at NYU that was constructed with support from a Research Facilities Improvement Grant (C06 RR-16572) from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The acquisition of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0958457).

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue celebrating Photochemistry and Photobiology's 55th Anniversary.

References

- 1.Moyzis RK, Buckingham JM, Cram LS, Dani M, Deaven LL, Jones MD, Meyne J, Ratliff RL, Wu JR. A highly conserved repetitive DNA sequence, (TTAGGG)n, present at the telomeres of human chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1988;85:6622–6626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verdun RE, Karlseder J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature. 2007;447:924–931. doi: 10.1038/nature05976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson JR, Raghuraman MK, Cech TR. Monovalent cation-induced structure of telomeric DNA: The G-quartet model. Cell. 1989;59:871–880. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Patel DJ. Solution structure of the human telomeric repeat d[AG3(T2AG3)3] G-tetraplex. Structure. 1993;1:263–282. doi: 10.1016/0969-2126(93)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luu KN, Phan AT, Kuryavyi V, Lacroix L, Patel DJ. Structure of the human telomere in K+ solution: an intramolecular (3 + 1) G-quadruplex scaffold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9963–9970. doi: 10.1021/ja062791w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansel-Hertsch R, Di Antonio M, Balasubramanian S. DNA G-quadruplexes in the human genome: detection, functions and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017;18:279–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD, Cawthon RM. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sciences U S A. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Su Y, Reus VI, Rosser R, Burke HM, Kupferman E, Compagnone M, Nelson JC, Blackburn EH. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress--preliminary findings. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt G, Jurk D, Marques FDM, Correia-Melo C, Hardy T, Gackowska A, Anderson R, Taschuk M, Mann J, Passos JF. Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:708. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. How easily oxidizable is DNA? One-electron reduction potentials of adenosine and guanosine radicals in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Insertion of specific bases during DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–434. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjelland S, Seeberg E. Mutagenicity, toxicity and repair of DNA base damage induced by oxidation. Mutat. Res. 2003;531:37–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasai H, Tanooka H, Nishimura S. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine residues in DNA by X-irradiation. Gann. 1984;75:1037–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourdat A-G, Douki T, Frelon S, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Tandem base lesions are generated by hydroxyl radical within isolated DNA in aerated aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4549–4556. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergeron F, Auvre F, Radicella JP, Ravanat JL. HO• radicals induce an unexpected high proportion of tandem base lesions refractory to repair by DNA glycosylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:5528–5533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000193107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. DNA lesions derived from the site-selective oxidation of guanine by carbonate radical anions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16:1528–1538. doi: 10.1021/tx034142t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidation of guanine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine by carbonate radical anions: Insight from oxygen-18 labeling experiments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005;44:5057–5060. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasai H, Yamaizumi Z, Berger M, Cadet J. Photosensitized formation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine) in DNA by riboflavin: a nonsinglet oxygen-mediated reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:9692–9694. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. One-electron oxidation of DNA and inflammation processes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:348–349. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0706-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravanat JL, Saint-Pierre C, Cadet J. One-electron oxidation of the guanine moiety of 2'-deoxyguanosine: influence of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2030–2031. doi: 10.1021/ja028608q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravanat JL, Di Mascio P, Martinez GR, Medeiros MH, Cadet J. Singlet oxygen induces oxidation of cellular DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:40601–40604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steenken S. Purine bases, nucleosides, and nucleotides: aqueous solution redox chemistry and transformation reactions of their radical cations and e- and OH adducts. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:503–520. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candeias LP, Steenken S. Reaction of HO• with guanine derivatives in aqueous solution: formation of two different redox-active OH-adduct radicals and their unimolecular transformation reactions. Properties of G(−H)•. Chem. Eur. J. 2000;6:475–484. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3765(20000204)6:3<475::aid-chem475>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douki T, Cadet J. Modification of DNA bases by photosensitized one-electron oxidation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1999;75:571–581. doi: 10.1080/095530099140212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Oxidatively generated damage to the guanine moiety of DNA: mechanistic aspects and formation in cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1075–1083. doi: 10.1021/ar700245e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafirovich V, Geacintov NE. Reactions of reactive nitrogen species and carbonate radical anions with DNA. In. In: Greenberg M, editor. Radical and radical ion reactivity in nucleic acid chemistry. John Willey&Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2009. pp. 325–355. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming AM, Muller JG, Burrows CJ. Characterization of 2'-deoxyguanosine oxidation products observed in the Fenton-like system Cu(II)/H2O2/reductant in nucleoside and oligodeoxynucleotide contexts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:3338–3348. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05112a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joffe A, Mock S, Yun BH, Kolbanovskiy A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidative generation of guanine radicals by carbonate radicals and their reactions with nitrogen dioxide to form site specific 5-guanidino-4-nitroimidazole lesions in oligodeoxynucleotides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16:966–973. doi: 10.1021/tx025578w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Combination of nitrogen dioxide radicals with 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and guanine radicals in DNA: Oxidation and nitration end-products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2191–2200. doi: 10.1021/ja044390r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidative DNA damage associated with combination of guanine and superoxide radicals and repair mechanisms via radical trapping. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32106–32115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rokhlenko Y, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Lifetimes and reaction pathways of guanine radical cations and neutral guanine radicals in an oligonucleotide in aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4955–4962. doi: 10.1021/ja212186w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rokhlenko Y, Cadet J, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Mechanistic aspects of hydration of guanine radical cations in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5956–5962. doi: 10.1021/ja412471u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleming AM, Burrows CJ. G-Quadruplex folds of the human telomere sequence alter the site reactivity and reaction pathway of guanine oxidation compared to duplex DNA. Chem. Res. Tox. 2013;26:593–607. doi: 10.1021/tx400028y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleming AM, Orendt AM, He Y, Zhu J, Dukor RK, Burrows CJ. Reconciliation of chemical, enzymatic, spectroscopic and computational data to assign the absolute configuration of the DNA base lesion spiroiminodihydantoin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18191–18204. doi: 10.1021/ja409254z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at GGG sequence by oxidative stress may accelerate telomere shortening. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00748-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oikawa S, Tada-Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Site-specific DNA damage at the GGG sequence by UVA involves acceleration of telomere shortening. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4763–4768. doi: 10.1021/bi002721g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su DG, Fang H, Gross ML, Taylor JS. Photocrosslinking of human telomeric G-quadruplex loops by anti cyclobutane thymine dimer formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:12861–12866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902386106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marky LA, Breslauer KJ. Calculating thermodynamic data for transitions of any molecularity from equilibrium melting curves. Biopolymers. 1987;26:1601–1620. doi: 10.1002/bip.360260911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mergny J-L, Phan A-T, Lacroix L. Following G-quartet formation by UV-spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1998;435:74–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rachwal PA, Fox KR. Quadruplex melting. Methods. 2007;43:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owczarzy R, Moreira BG, You Y, Behlke MA, Walder JA. Predicting stability of DNA duplexes in solutions containing magnesium and monovalent cations. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5336–5353. doi: 10.1021/bi702363u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Candeias LP, Steenken S. Structure and acid-base properties of one-electron-oxidized deoxyguanosine, guanosine, and 1-methylguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:1094–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV, Bietti M, Bernhard K. The trap depth (in DNA) of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'deoxyguanosine as derived from electron-transfer equilibria in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2373–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi K, Tagawa S. Direct observation of guanine radical cation deprotonation in duplex DNA using pulse radiolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10213–10218. doi: 10.1021/ja036211w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi K, Yamagami R, Tagawa S. Effect of base sequence and deprotonation of guanine cation radical in DNA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:10752–10757. doi: 10.1021/jp804005t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivanov KL, Glebov EM, Plyusnin VF, Ivanov YV, Grivin VP, Bazhin NM. Laser flash photolysis of sodium persulfate in aqueous solution with additions of dimethylformamide. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. 2000;133:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McElroy WJ. A laser photolysis study of the reaction of SO4- with Cl- and the subsequent decay of Cl2- in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:2435–2441. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Candeias LP, Steenken S. Electron transfer in di(deoxy)nucleoside phosphates in aqueous solution: rapid migration of oxidative damage (via adenine) to guanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:2437–2440. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolf P, Jones GD, Candeias LP, O'Neill P. Induction of strand breaks in polyribonucleotides and DNA by the sulphate radical anion: role of electron loss centres as precursors of strand breakage. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1993;64:7–18. doi: 10.1080/09553009314551061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seidel CAM, Schulz A, Sauer MHM. Nucleobase-specific quenching of fluorescent dyes. 1. Nucleobase one-electron redox potentials and their correlation with static and dynamic quenching efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:5541–5553. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall DB, Holmlin RE, Barton JK. Oxidative DNA damage through long-range electron transfer. Nature. 1996;382:731–735. doi: 10.1038/382731a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nunez ME, Hall DB, Barton JK. Long-range oxidative damage to DNA: effects of distance and sequence. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:85–97. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giese B. Long-distance charge transport in DNA: The hopping mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:631–636. doi: 10.1021/ar990040b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuster GB. Long-range charge transfer in DNA: Transient structural distortions control the distance dependence. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar980059z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berlin Y, Burin AL, Ratner MA. Charge hopping in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:260–268. doi: 10.1021/ja001496n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis FD, Zhu H, Daublain P, Fiebig T, Raytchev M, Wang Q, Shafirovich V. Crossover from superexchange to hopping as the mechanism for photoinduced charge transfer in DNA hairpin conjugates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:791–800. doi: 10.1021/ja0540831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hildenbrand K, Schulte-Frohlinde D. ESR spectra of radicals of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA in aqueous solution. Implications for •OH-induced strand breakage. Free Rad. Res. Commun. 1990;11:195–206. doi: 10.3109/10715769009088916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bachler V, Hildenbrand K. EPR-detection of the guanosyl radical cation in aqueous solution. Quantum chemically supported assignment of nitrogen and proton hyperfine couplings. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1992;40:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. The guanine cation radical: Investigation of deprotonation states by ESR and DFT. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:24171–24180. doi: 10.1021/jp064361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adhikary A, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Direct observation of the hole protonation state and hole localization site in DNA-oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8614–8619. doi: 10.1021/ja9014869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Munafo SA, Khanduri D, Sevilla MD. Prototropic equilibria in DNA containing one-electron oxidized GC: intra-duplex vs. duplex to solvent deprotonation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12:5353–5368. doi: 10.1039/b925496j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shao J, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine by oxyl radicals produced by photolysis of azo compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:933–938. doi: 10.1021/tx100022x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crean C, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Pathways of arachidonic acid peroxyl radical reactions and product formation with guanine radicals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:358–373. doi: 10.1021/tx700281e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]