Abstract

Background

MRI does not offer a direct method to obtain attenuation correction maps as its predecessors (stand-alone PET and PET/CT), and bone visualisation is particularly challenging. Recently, zero-echo-time (ZTE) was suggested for MR-based attenuation correction (AC). The aim of this work was to evaluate ZTE- and atlas-AC by comparison to 68Ge-transmission scan-based AC.

Nine patients underwent brain PET/MR and stand-alone PET scanning using the dopamine transporter ligand 11C-PE2I. For each of them, two AC maps were obtained from the MR images: an atlas-based, obtained from T1-weighted LAVA-FLEX imaging with cortical bone inserted using a CT-based atlas, and an AC map generated from proton-density-weighted ZTE images. Stand-alone PET 68Ge-transmission AC map was used as gold standard. PET images were reconstructed using the three AC methods and standardised uptake value (SUV) values for the striatal, limbic and cortical regions, as well as the cerebellum (VOIs) were compared. SUV ratio (SUVR) values normalised for the cerebellum were also assessed. Bias, precision and agreement were calculated; statistical significance was evaluated using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test.

Results

Both ZTE- and atlas-AC showed a similar bias of 6–8% in SUV values across the regions. Correlation coefficients with 68Ge-AC were consistently high for ZTE-AC (r 0.99 for all regions), whereas they were lower for atlas-AC, varying from 0.99 in the striatum to 0.88 in the posterior cortical regions. SUVR showed an overall bias of 2.9 and 0.5% for atlas-AC and ZTE-AC, respectively. Correlations with 68Ge-AC were higher for ZTE-AC, varying from 0.99 in the striatum to 0.96 in the limbic regions, compared to atlas-AC (0.99 striatum to 0.77 posterior cortex).

Conclusions

Absolute SUV values showed less variability for ZTE-AC than for atlas-AC when compared to 68Ge-AC, but bias was similar for both methods. This bias is largely caused by higher linear attenuation coefficients in atlas- and ZTE-AC image compared to 68Ge-images. For SUVR, bias was lower when using ZTE-AC than for atlas-AC. ZTE-AC shows to be a more robust technique than atlas-AC in terms of both intra- and inter-patient variability.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40658-018-0220-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Attenuation correction, PET/MR, ZTE-AC, Atlas-AC, Static imaging

Background

Attenuation correction (AC) is still a major challenge for PET/MR [1–3], and accurate AC is required for quantitative PET imaging [4]. In stand-alone PET systems, 68Ge-transmission scans using rotating rod sources are used for AC [5–7]. Since photon attenuation values are directly measured at 511 keV, this is considered as gold standard in AC [8]. For PET/CT, a low-dose CT scan is acquired for AC, and attenuation coefficients are approximated by conversion from Hounsfield units using well-established methods [5]. PET/MR scanners do not offer a direct method to obtain attenuation maps as the stand-alone PET and PET/CT scanners [2, 7, 9], since MR measures proton density which does not correlate directly to electron density [3, 10]. Furthermore, most MR sequences show little signal in bone and air. Linear attenuation coefficients (cm−1) at 511 keV vary between 0 in air, 0.151 in bone and 0.96 in water (6), posing a challenge for MR-based AC. Since ignoring bone may lead to a regional bias, as demonstrated for example by Andersen et al. [11], new methods for MR-derived attenuation maps have been developed and incorporated into the commercially available systems [2, 7].

PET/MR systems have relied on segmentation-based routines for AC, which use 3D fat/water separated imaging for segmentation into four tissue classes (air, lung, soft and adipose tissue), and 511 keV attenuation coefficients are assigned to each tissue class. However, these methods do not consider bone tissue. Therefore, an atlas-based method was introduced using a skull template being co-registered to the individual patient’s data [12]. The reliability of atlas-based AC is associated with how well the template matches the individual patient’s skull. As reported before [13], the atlas method shows good accuracy in the cortex and central parts of the brain, but poor accuracy in the cerebellum when compared to CT-based AC.

A number of other atlas-based methods have been presented as well, for example, the multi-atlas approach by Burgos et al. [14, 15], validated by Sekine et al. [16] and Merida et al. [17], which uses a probabilistic method to synthesise a subject-specific pseudo-CT by registering each atlas to the target subject space. Rezaei et al. [18] proposed a time-of-flight maximum likelihood reconstruction of attenuation and activity (TOF-MLAA) approach, based on the method described by Nuyts et al. [19, 20] to reduce the inaccuracy of MR-AC methods that do not take TOF in consideration. This method was tested by Salomon et al. [21] and Boellaard et al. [22] for improving the accuracy of PET/MR studies using TOF. Keereman et al. [23] proposed using ultrashort echo time (UTE) as a method to visualise the cortical bone and integrate it into MR-based attenuation maps, using a first echo time between 70 and 150 μs. In a recent multi-centre study, Ladefoged et al. [24] compared 11 different MR-AC methods based on the data from a single, non-TOF, integrated PET/MR system (Biograph mMR, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). The first and second echo times for UTE in that paper were 0.07 and 2.46 ms, respectively. It was found that for all AC methods, global radioactivity concentrations are within ± 5% of those derived from CT-based AC.

Recently, a zero-echo-time (ZTE)-based segmentation method [25, 26] has been suggested for eight MR-based AC. ZTE was designed to achieve signal from the cortical bone for tissue segmentation [25–27], and as such can be used to incorporate the bone in MR-based attenuation correction. Sekine et al. [27] assessed the effectiveness and feasibility of ZTE-based AC in a clinical setting compared to CT-based attenuation correction.

The aim of this work was to compare the performance of ZTE- and atlas-based AC using 68Ge-transmission scan-based AC as a gold standard. For this purpose, we used the dopamine transporter imaging tracer PE2I in subjects with Parkinsonism. Accuracy and precision were obtained for standardised uptake values (SUV), as well as SUV ratios normalised to the cerebellum, for different clusters of regions across the brain.

Methods

Subjects

Ten patients with Parkinsonism (five male, five female; median age 72 years, range 49–82) were recruited by the Department of Neurology at Uppsala University Hospital. Inclusion criteria were (1) at least 40 years of age, (2) a previous clinical 11C-PE2I scan on a stand-alone PET scanner, (3) able to undergo an 80-min PET/MR scan and (4) no implants that prohibit MR imaging. One patient was excluded due to technical problems during the image acquisition. This study was approved by the Regional Board of Medical Ethics in Uppsala as well as the Radiation Ethics Committee of Uppsala University Hospital, and all the subjects signed an informed consent prior to inclusion.

Data acquisition and image reconstruction

A 10-min 68Ge-transmission scan using rotating 68Ge rod sources was acquired as part of each subject’s prior investigation on a stand-alone PET system (ECAT Exact HR+, Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN) [28]. The transmission scan was acquired before tracer administration and hence was free from emission contamination.

PET/MR scans were acquired on a 3 T PET/MR (Signa PET/MR, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI), which combines a 3-T MRI with a time-of-flight (TOF)-capable silicone photomultiplier (SiPM)-based PET scanner [29]. Patients were scanned in a supine position using an eight-channel head coil (MR Instruments Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The acquisition protocol was comprised of an 80-min list-mode PET scan starting simultaneously with intravenous administration of 5 MBq/kg 11C-PE2I using an infusion pump.

For standard AC, a T1-weighted 3D LAVA Flex was acquired for 18 s with 1 NEX, 500 mm FOV, 5.2 mm slice thickness, matrix 256 × 256 and 5° flip angle. The LAVA Flex sequence generates four image sets (water and fat, in- and out phase) used for MR-AC map generation. Finally, the ZTE acquisition, based on the paradigm proposed by Wiesinger et al. and Delso et al. [25, 26], was acquired for 153 s using 4 NEX, 260 mm FOV, 1.4 mm slice thickness, no slice gap, matrix 192 × 192 and 0.8° flip angle. Finally, a T1-weighted image was acquired for 272 s using a 3D Brain Volume Imaging (BRAVO) sequence with 1 NEX, 250 mm FOV, 1 mm slice thickness, 12° flip angle and a 256 × 256 matrix.

PET images were reconstructed using time-of-flight ordered subsets expectation maximisation (OSEM) with 2 iterations, 28 subsets, a 5-mm Gaussian post-filter, a 192 × 192 reconstruction matrix and a 600-mm FOV. All appropriate corrections, such as for random coincidences and scatter, were applied. Attenuation correction was performed as described in the next section.

Attenuation correction maps

For each patient, three attenuation correction maps were generated:

-

Atlas-based AC

The atlas-based AC map was generated using a vendor-implemented process comprised of four main steps and taking approximately 30 s with no external interaction [12, 13, 27]. This four-step process consists of (1) T1-weighted image undergoing a Hessian bone enhancement, (2) pseudo-CT generation by rigid and non-rigid B-spline registration of the enhanced image to a CT-based head atlas, (3) generation of an attenuation map from the pseudo-CT using standard energy conversion and resampling and (4) addition of coils and bed to the attenuation map using a CT-based template.

-

ZTE-based AC

This method consists of intensity equalisation [30] followed by logarithmic rescaling to enhance bone tissue and application of a mask to isolate patient data from background and coil elements. The masked image is submitted to a series of threshold operations to define bone and air regions using Gaussian fitting of the main histogram peaks. As a final step, internal air compartments are identified using simple histogram thresholding. The resulting image was co-registered to the patient section of the atlas-AC with coils and bed removed, using rigid-body registration with six degrees of freedom (DOF) and then replaced the patient’s data of the atlas-AC map to create a ZTE-based attenuation map [25, 26]. CT-based template containing coils and bed information was then added again. A more detailed description can be found in Wiesinger et al. [26].

-

Transmission-based AC

Attenuation sinograms were computed by division of the transmission sinogram with a blank scan sinogram, acquired using rotating 68Ge rod sources around an empty FOV as part of the daily quality control of the ECAT scanner as implemented in the scanner software. Attenuation maps were reconstructed from the 68Ge-transmission data using OSEM with six iterations, eight subsets and a 4-mm Hanning post-filter. A mask was applied to the 68Ge attenuation map to remove the bed and head support as well as noise outside the head, and the 68Ge attenuation map was co-registered to the head atlas attenuation map with coils and bed removed using six DOF rigid-body registration. Then, the head in the atlas-AC map was replaced by the 68Ge-AC map head section. Finally, the coil and bed CT-based template was incorporated into the AC map again. Processing steps were executed using an in-house developed MATLAB pipeline (MATLAB R2015a, Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA).

Using these AC maps, three PET datasets were created, which from here on will be referred to as atlas-AC, ZTE-AC and 68Ge-AC.

To evaluate how possible differences between attenuation coefficient values in the different attenuation maps affected the results, atlas- and ZTE-AC maps were rescaled to match 68Ge-AC values, and the analysis was repeated. This is described in more detail in Additional file 1.

Data analysis

For visual assessments, all PET images were spatially normalised using statistical parametric mapping (SPM8; Welcome Trust Centre for Neurological Imaging, London, UK). Then, mean SUV images and mean parametric bias images were generated for 68Ge-, ZTE- and atlas-AC.

Atlas-AC, ZTE-AC and 68Ge-AC PET images were compared considering uptake values in various brain regions. Agreement between methods was assessed using measures of accuracy, precision and correlations. For this purpose, volumes of interest (VOIs) were placed over the T1-weighted structural MR images using an automated probabilistic VOI template as implemented in the PVElab software [31] and transferred to the co-registered PET images in each dataset. Standardised uptake values (SUV) for each VOI were obtained by retrieving average regional voxel values from all PET images and normalising these to the amount of injected radioactivity per body weight. Then, the SUV values were normalised to cerebellar grey matter to obtain SUV ratio (SUVR) values.

Four clusters of VOIs were created: anterior cortical regions (ACR—cingulate, frontal gyrus), posterior cortical regions (PCR—occipital cortex, parietal cortex and somatosensory motor cortex), striatal regions (STR—caudate nucleus, putamen) and limbic regions (LR—amygdala, hippocampus, hypothalamus and thalamus) [32]. In addition, the whole brain grey matter (WB) and cerebellum (CER) were considered, where the cerebellum is of importance as it is used as a reference region in kinetic analysis for 11C-PE2I [32, 33] and many other receptor ligands.

For the comparisons, we used (1) the relative difference in SUV and SUVR between ZTE- or atlas-AC and 68Ge-AC (bias; Eq. 1), (2) the standard deviation of the bias (precision) and (3) correlations based on orthogonal regression analysis, assuming equal error variance of the three AC methods.

Bias was calculated as

| 1 |

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California). A non-parametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was applied to detect statistically significant differences in bias between AC methods (p < 0.05).

Results

Figure 1 illustrates 68Ge-, atlas- and ZTE-AC maps, as well as corresponding SUV images, for one typical patient with Parkinsonism, showing visually obvious differences between the three AC maps. However, the resulting PET images are visually similar for all cases.

Fig. 1.

First row, left to right—68Ge-, Atlas- and ZTE-attenuation correction (AC) maps; Second row—11C-PE2I PET images based on corresponding AC maps expressed as standardised uptake values (SUV)

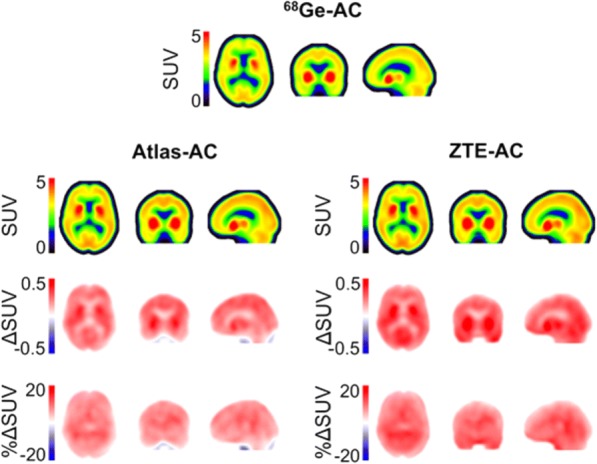

Mean 68Ge -, atlas- and ZTE-AC SUV images are shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating similar patterns. Mean parametric bias images for ZTE- and atlas-AC compared to 68Ge-AC indicated a mostly positive bias in SUV values across the brain for both methods (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean 11C-PE2I SUV images using 68Ge-AC (first row) as well as atlas-AC and ZTE-AC (second row). Below, average absolute and relative SUV images illustrating absolute (ΔSUV) and relative (%ΔSUV) differences between atlas-AC (left) and ZTE-AC (right) compared to 68Ge-AC

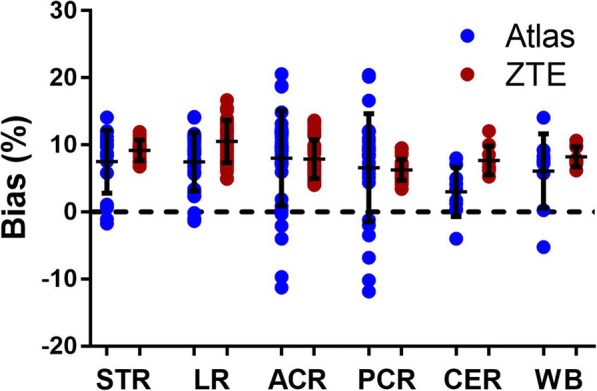

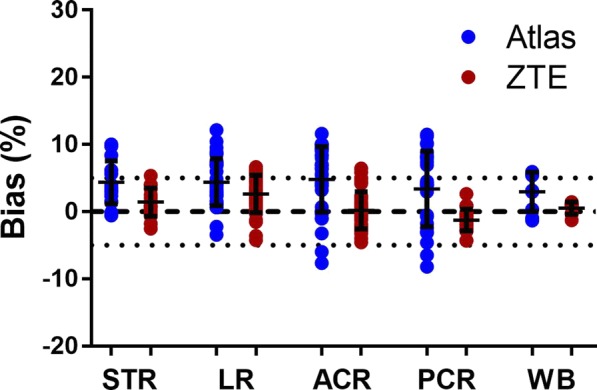

Biases in SUV for 68Ge - and atlas-AC compared to ZTE-AC are given for different brain regions in Fig. 3. Both ZTE- and atlas-AC resulted in an overall overestimation of SUV values. Inter-subject variability was larger for atlas-AC than ZTE-AC. Atlas-AC showed a larger inter-subject variability in the cortical regions compared to the striatal and limbic regions.

Fig. 3.

Relative bias in SUV after use of ZTE- or atlas-attenuation correction (AC) compared to 68Ge-AC for different regions of interest. STR, striatum; LR, limbic regions; ACR, anterior cortical regions; PCR, posterior cortical regions; CER, cerebellum; WB, whole-brain. Bars and whiskers are mean ± SD

Quantitative measures of bias in SUV are given for various brain regions in Table 1. Bias was similar for atlas- and ZTE-AC in the cortical regions, about 6–8%. For both CER and LR, the bias is considerably higher in ZTE-AC (8–11%) than for atlas-AC (3–5%). As an overall measure, WB SUV values were slightly higher in ZTE-AC (8.2%) than in atlas-AC (6.1%). The corresponding average SD of the bias was considerably smaller for ZTE-AC (1.5–3.2%) than for atlas-AC (3.7–8.1%). As shown in Additional file 1, this bias is considerably reduced for both methods when rescaling the AC maps to mean 68Ge-AC map values.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficient r, slope and intercept of orthogonal regression across subjects for SUV values in different brain clusters when comparing ZTE- and atlas-attenuation correction (AC) with 68Ge-AC. In addition, mean bias (%) and accuracy (SD of % bias) are given

| AC | Brain region | r | Slope | Intercept | % bias | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZTE | STR | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.09 | 9.2* | 1.6 |

| LR | 0.99 | 1.07 | 0.06 | 10.5* | 3.2 | |

| ACR | 0.99 | 1.09 | − 0.01 | 7.9* | 2.9 | |

| PCR | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 6.3* | 1.6 | |

| CER | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.08 | 7.7* | 2.2 | |

| WB | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 8.2* | 1.5 | |

| Atlas | STR | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.27 | 7.5* | 4.7 |

| LR | 0.97 | 1.03 | 0.07 | 4.5* | 4.4 | |

| ACR | 0.92 | 1.06 | 0.02 | 8.0* | 7.1 | |

| PCR | 0.88 | 1.03 | 0.05 | 6.6* | 8.1 | |

| CER | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.17 | 3.0 | 3.7 | |

| WB | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.10 | 6.1* | 5.6 |

STR striatum, LR limbic regions, ACR anterior cortical regions, PCR posterior cortical regions, CER cerebellum, WB whole-brain

*p value < 0.05

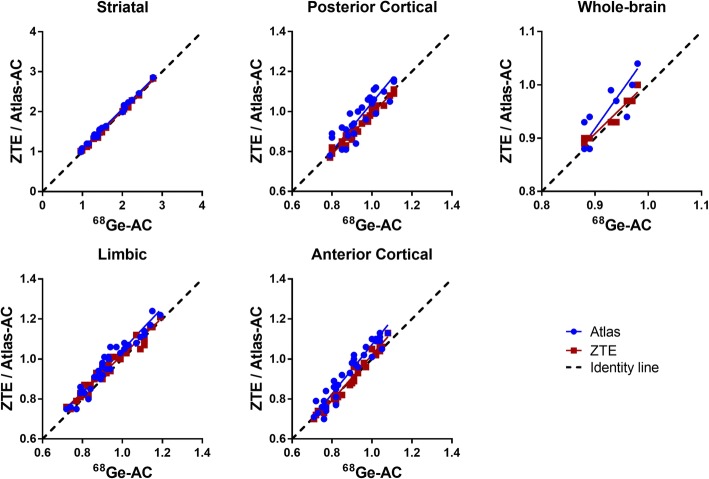

The relationship in SUV between 68Ge-AC and ZTE-/atlas-AC is demonstrated for various brain regions in Fig. 4. Correlation coefficient values were close to 1 for ZTE-AC (0.99) for all regions, whereas r values for atlas-AC were still high but more variable (0.88–0.99) Table 1. The slopes of the regression lines were slightly higher than identity across all brain regions for ZTE-AC (1.03–1.09). In contrast, atlas-AC slopes were both lower and higher than the identity (0.92–1.06), depending on the region.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between SUV for different brain regions when using 68Ge-attenuation correction (AC; gold standard) and ZTE- or atlas-AC. Solid lines represent Deming regressions, and the dashed lines represent identity

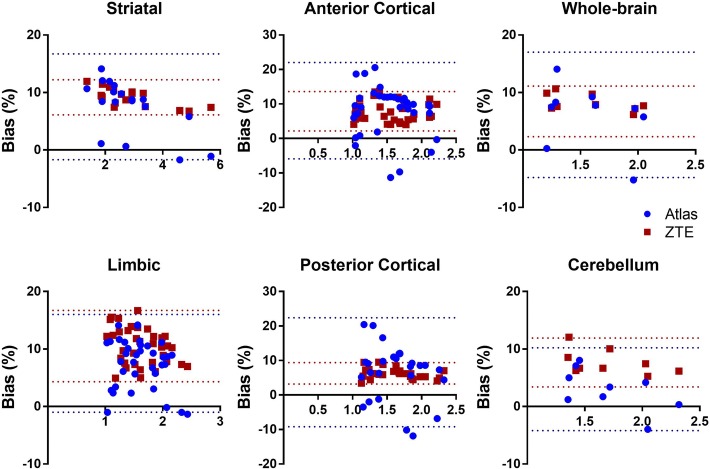

In Fig. 5, bias in SUVR is given for ZTE- and atlas-AC compared to 68Ge-AC considering the different brain regions. Both ZTE- and atlas-AC resulted in a significant overestimation of SUVR values, except in PCR for ZTE-AC. Again, inter-subject variation was larger for atlas-AC compared to ZTE-AC, where the largest variability was found in the cortical regions when using atlas-AC. For SUVR, relative bias and its SD were smaller for ZTE-AC than for atlas-AC for all brain regions (Table 2), especially for the cortical regions (ACR and PCR). Bias in SUVR values varied between 2.9 and 4.8% for atlas-AC and between − 1.3 and 2.6% for ZTE-AC across the regions. The average SD of the bias was considerably smaller for ZTE-AC (0.9–2.8%) than for atlas-AC (2.9–5.6%).

Fig. 5.

Relative bias in SUVR after use of ZTE- or atlas-attenuation correction (AC) compared to 68Ge-AC for different regions of interest. STR, striatum; LR, limbic regions; ACR, anterior cortical regions; PCR, posterior cortical regions; WB, whole-brain. Bars and whiskers are mean ± SD

Table 2.

Correlation coefficient r, slope and intercept of orthogonal regression across subjects for SUVR values in different brain clusters when comparing ZTE- and atlas-attenuation correction (AC) with 68Ge-AC. In addition, mean bias (%) and accuracy (SD of % bias) are given

| AC | Brain region | r | Slope | Intercept | % bias | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZTE | STR | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.4* | 2.1 |

| LR | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.08 | 2.6* | 2.8 | |

| ACR | 0.97 | 1.14 | − 0.12 | 0.2 | 2.8 | |

| PCR | 0.97 | 1.01 | − 0.02 | − 1.3* | 1.6 | |

| WB | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| Atlas | STR | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 4.4* | 3.2 |

| LR | 0.94 | 0.94 | − 0.01 | 4.4* | 3.5 | |

| ACR | 0.92 | 1.23 | − 0.16 | 4.8* | 4.8 | |

| PCR | 0.77 | 1.21 | − 0.17 | 3.4* | 5.6 | |

| WB | 0.68 | 1.41 | − 0.35 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

STR striatum, LR limbic regions, ACR anterior cortical regions, PCR posterior cortical regions, WB whole-brain

*p value < 0.05

In Fig. 6, the relationship in SUVR between 68Ge-AC and ZTE-/atlas-AC is illustrated for various brain regions. Correlation coefficients were higher for ZTE-AC (0.94 WB, 0.99 STR) than for atlas-AC (0.68 WB, 0.99 STR), Table 2. The slopes of the regression curves were similar in the subcortical regions (STR, LR) for both AC methods. However, the slopes differed considerably from unity in the cortical regions (1.21–1.23) and WB (1.41) for atlas-AC, but not for ZTE-AC.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between SUVR for different brain regions when using 68Ge-attenuation correction (AC; gold standard) and ZTE-or atlas-AC. Solid lines represent Deming regressions, and the dashed lines represent identity

Discussion

In the present work, the accuracy and precision of an MR-AC method based on a proton-density-weighted ZTE sequence were compared to an atlas-based method and the gold standard for PET attenuation correction—the transmission scan with rotating 68Ge rod sources [8]. In contrast, other reports [12, 13, 27, 34–39] on MR-AC were all using 18F-FDG PET and using CT-based AC as a reference. Two challenges when using 68Ge-transmission scans are that they are prone to noise and can suffer from emission spill-over. In the present work, emission spillover was avoided since all transmission scans were acquired before injecting the subjects with 11C-PE2I [40].

ZTE-AC presented smaller variability and hence higher precision than atlas-AC. The overall bias in SUV for both atlas-AC and ZTE-AC is probably to a large extent caused by higher linear attenuation coefficients in both ZTE and atlas AC maps compared to 68Ge-AC map. SUVR analysis from all brain regions and whole brain showed smaller inter-patient variation and higher accuracy for ZTE-AC compared to atlas-AC. In addition, correlation and agreement between 68Ge-AC SUV and ZTE-/atlas-AC were constantly higher for ZTE- than for atlas-AC. Although the accuracy of atlas-AC SUV was better than that of ZTE-AC, showing a smaller mean bias compared to 68Ge-AC, the precision of SUV and both accuracy and precision of SUVR were better for ZTE-AC than for atlas-AC when compared to 68Ge-AC. A better precision corresponds to a smaller variability in bias and hence more robust and predictable results.

The improvements on SUV data resulting from the use of ZTE-AC are visible as a higher correlation and improved precision compared to 68Ge-AC in the cerebellum and PCR (Figs. 3 and 4; Table 1). Similar improvements in the cerebellum have been reported before and can be attributed to improved estimation of the temporal bone [27, 39]. As previously reported [11, 27, 38], misclassification and regular bias using atlas-AC are caused by the slim temporal bone, which may lead to a bias of uptake values in axial slices with lines of response crossing the temporal bone.

Some misclassifications are visible in the ZTE-AC map (Fig. 1, top right), mostly located around the nasal area, which may lead to cerebellum bias at the level of the sinus. An accurate AC in the cerebellum is of importance since it is used as a reference region for normalisation in studies of neuroreceptor and neurotransporter ligands [41]. These misclassifications are likely caused by the non-continuous mapping of ZTE intensities to attenuation coefficients, which affects mainly the soft tissue near tissue-air interfaces [1, 25, 26, 38, 39]. As a further improvement to the method used in the present study, Yang et al. [39] proposed a sinus and air-tissue interface correction for ZTE-AC to deal with this drawback, reducing SUV bias in the cerebellum from 8% in uncorrected ZTE to 0.6% using sinus correction in their work. However, the present work shows that bias in ZTE-AC SUV values in the cerebellum is comparable to the rest of the brain, Fig. 7. This results in a bias in SUVR, normalised to the cerebellum, compared to 68Ge-AC, of no more than a few percent, with much less variability than for atlas-AC (Fig. 8). Hence, in this respect, the present ZTE-AC implementation can be considered to perform sufficiently accurate for receptor ligand studies using the cerebellum as a reference tissue.

Fig. 7.

SUV bias plots of ZTE-AC and atlas-AC compared to 68Ge-AC for different brain regions. Dashed lines represent confidence intervals associated to ZTE-AC and atlas-AC

Fig. 8.

SUVR bias plots of ZTE-AC and atlas-AC compared to 68Ge-AC for different brain regions. Dashed lines represent confidence intervals associated to both comparisons

Previous studies using 18F-FDG have reported smaller mean MR-AC biases in SUV, ranging between − 0.1 and 5.6% for the whole brain [34–37, 39], compared to 8.2% (SUV) and 0.5% (SUVR) for ZTE-AC in the present study. Our results are, however, difficult to compare to those results as these previous studies compared PET/MR-AC to CT-AC, sometimes referred to as the ‘silver standard’ for AC [27], instead of 68Ge-AC. CT-AC in itself has been reported as having a mean SUV bias of 2–6% when compared to 68Ge-AC in whole-body 18F-FDG scans [42, 43]. Although, to our knowledge, no direct comparison between CT-AC and 68Ge-AC in the brain scans has been reported, a similar bias could be expected when using CT-AC in the brain.

ZTE-AC and atlas-AC were used as developed by the manufacturer and implemented in the commercial reconstruction software and the research toolbox of the Signa PET/MR, respectively, at the time of the study [8], with the ZTE-AC method as used in the present work being scheduled for commercial release in 2018. Recent improvements of atlas-based methods in comparison with the method implemented in the scanner, such as the multi-atlas approach by Ninon et al. [14, 15] and the probabilistic atlas method described by Merida et al. [17], might have resulted in more favourable results for atlas-based methods but were outside the scope of this work, as were the evaluation of further developments of ZTE-AC [39]. ZTE- and atlas-AC methods used in this study apply an attenuation coefficient of 0.1 cm−1 in the brain tissue, as does the CT-AC method used by Sekine et al. [27] and many, if not all, clinical PET/CT scanners. However, the mean value of the brain tissue attenuation coefficient in 68Ge-based attenuation maps used in the present work is about 0.097 cm−1. To assess whether this 3% discrepancy can explain the differences between ZTE- and atlas-AC SUV compared to 68Ge-AC in our results, especially in relation to previous studies comparing to CT-AC, ZTE- and atlas-AC maps were rescaled to mean 68Ge-AC values using a weighted rescaling to account for differences in scale factors in the brain tissue and bone. PET images were reconstructed using both scaled ZTE- and atlas-AC and analysed again as described in Additional file 1. This led to much smaller biases between MR-AC and 68Ge-AC, as shown in the Additional file 1: Figures S2 and S3), which is more in line with published data comparing to CT-AC [1, 13, 27, 34–36, 39, 44]. Also, after rescaling, ZTE-AC did not provide smaller biases than atlas-AC when compared to 68Ge-AC, but ZTE-AC did have a considerably better accuracy, similar as when comparing the original ZTE-AC and atlas-AC images to 68Ge-AC. The full rescaling results can be found in Additional file 1.

One of the limitations of the present work is that the Signa PET/MR scanner has a greater axial FOV than the ECAT scanner [28]. Therefore, the part of the PET/MR FOV that was not covered by the 68Ge-AC image used data from the atlas-AC map. Consequently, the lines of response associated with regions completed by this method may have suffered from a bias towards atlas-AC. However, this effect should be more of an issue for regions below the brain than inside the brain. A 60-cm transaxial FOV with 192 × 192 matrix was used, which results in larger pixel sizes than routinely used in brain studies. Given that rather large regions were used in the analysis, this is unlikely to affect our conclusions. Furthermore, a limited number of subjects (N = 9) was included, none of which presented any skull anomalies. The inclusion of patients with missing bone or otherwise abnormal skull would probably have resulted in much larger differences between atlas- and ZTE-AC but were outside the scope of the present work.

Finally, an evaluation of kinetic parameters based on the dynamic PET, such as binding potential and relative cerebellar blood flow, should be assessed to properly understand the use of ZTE-AC for quantitative brain-PET and will be subject of future work.

Conclusions

The results of the present study show that ZTE-AC is a more robust technique than the clinically implemented atlas-AC method in terms of both inter- and intra-patient variability. ZTE- and atlas-AC had a similar bias in SUV compared with 68Ge-AC. The bias in SUV is largely caused by higher linear attenuation coefficients in both ZTE- and atlas-AC maps compared to 68Ge-AC map. However, ZTE-AC presented smaller variability and hence higher precision than atlas-AC. SUVR analysis also showed smaller inter-patient variation in addition to higher accuracy for ZTE-AC compared to atlas-AC. ZTE-based AC for quantitative PET brain studies provides a major improvement in comparison to the currently implemented atlas-based method.

Additional file

Effects of rescaling atlas and ZTE-AC maps to 68Ge-AC values. (DOCX 336 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Anders Lundberg, Marie Åhlman and Martin Skytt, Uppsala University, for the patient handling and image acquisitions; the radiochemistry staff at Uppsala PET Centre for the production of 11C-PE2I; and the patients for agreeing in taking part in this study. Further, we would like to thank Gaspar Delso and Florian Wiesinger, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA, for the software support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, grant no. 2011-6269 and the Regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Uppsala County and Uppsala University Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author, João M. Sousa (joao.sousa@surgsci.uu.se), for the data used in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3D

Three-dimensional

- AC

Attenuation correction

- CT

Computer tomography

- DOF

Degree(s) of freedom

- FDG

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- FOV

Field-of-view

- MLAA

Maximum likelihood estimation of activity and attenuation

- MR

Magnetic resonance

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NEX

Number of excitations

- OSEM

Ordered subset expectation maximisation

- PE2I

N-(3-iodopro-2E-enyl)-2beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4′-methylphenyl) nortropane

- PET

Positron emitting tomography

- SUV

Standardised uptake value

- SUVr

Standardised uptake value ratio

- TOF

Time-of-flight

- UTE

Ultrashort echo time

- ZTE

Zero echo time

Authors’ contributions

JMS performed the reconstructions, built the imaging analysis pipeline, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. ME provided assistance in the construction of the image analysis pipeline and reconstructions and critically evaluated the manuscript. LA and ML designed the study and contributed to the data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. SP and DN were responsible for the patient recruitment and critically evaluated the manuscript. EML and HA contributed to the study design and critical evaluation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Mathias Engström is an employee of GE Healthcare. Håkan Ahlström and Mark Lubberink receive research support from GE Healthcare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Delso G, Wiesinger F, Sacolick LI, Kaushik SS, Shanbhag DD, Hullner M, et al. Clinical evaluation of zero-echo-time MR imaging for the segmentation of the skull. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2015;56:417–422. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.149997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagenknecht G, Kaiser HJ, Mottaghy FM, Herzog H. MRI for attenuation correction in PET: methods and challenges. Magn Reson Mater Physics Biol Med. 2013:99–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Keereman V, Mollet P, Berker Y, Schulz V, Vandenberghe S. Challenges and current methods for attenuation correction in PET/MR. Magn Reson Mater Physics Biol Med. 2013;26:81–98. doi: 10.1007/s10334-012-0334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, Phelps ME, Kuhl DE. Quantitation in positron emission computed tomography: 2. Effects of inaccurate attenuation correction. J Comput Assist Tomogr United States. 1979;3:804–814. doi: 10.1097/00004728-197903060-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai C, Shao L, Da Silva AJ, Zhao Z. A generalized model for the conversion from CT numbers to linear attenuation coefficients. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2003;50:1510–1515. doi: 10.1109/TNS.2003.817281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navalpakkam BK, Braun H, Kuwert T, Quick HH. Magnetic resonance-based attenuation correction for PET/MR hybrid imaging using continuous valued attenuation maps. Investig Radiol. 2013;48:323–332. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318283292f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezrukov I, Mantlik F, Schmidt H, Schölkopf B, Pichler BJ. MR-based PET attenuation correction for PET/MR imaging. Semin Nucl Med [Internet]. Elsevier Inc. 2013;43:45–59. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schramm G, Langner J, Hofheinz F, Petr J, Beuthien-Baumann B, Platzek I, et al. Quantitative accuracy of attenuation correction in the Philips Ingenuity TF whole-body PET/MR system: a direct comparison with transmission-based attenuation correction. Magn Reson Mater Physics Biol Med [Internet]. Springer-Verlag. 2013;26:115–126. doi: 10.1007/s10334-012-0328-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong JH, Cho IH, Kong EJ, Chun KA. Evaluation of Dixon sequence on hybrid PET/MR compared with contrast-enhanced PET/CT for PET-positive lesions. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;48:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s13139-013-0240-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann M, Pichler B, Schölkopf B, Beyer T. Towards quantitative PET/MRI: a review of MR-based attenuation correction techniques. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:93–104. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen FL, Ladefoged CN, Beyer T, Keller SH, Hansen AE, Højgaard L, et al. Combined PET/MR imaging in neurology: MR-based attenuation correction implies a strong spatial bias when ignoring bone. Neuroimage. Elsevier Inc. 2014;84:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wollenweber SD, Ambwani S, Delso G, Lonn AHR, Mullick R, Wiesinger F, et al. Evaluation of an atlas-based PET head attenuation correction using PET/CT &: MR patient data. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci [Internet] 2013;60:3383–3390. doi: 10.1109/TNS.2013.2273417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekine T, Buck A, Delso G, Ter Voert EEGW, Huellner M, Veit-Haibach P, et al. Evaluation of atlas-based attenuation correction for integrated PET/MR in human brain: application of a head atlas and comparison to true CT-based attenuation correction. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:215–220. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgos N, Cardoso MJ, Thielemans K, Modat M, Pedemonte S, Dickson J, et al. Attenuation correction synthesis for hybrid PET-MR scanners: application to brain studies. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet]. 2014;33:2332–41. [cited 27 Mar 2018]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25055381. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Burgos N, Cardoso MJ, Thielemans K, Modat M, Dickson J, Schott JM, et al. Multi-contrast attenuation map synthesis for PET/MR scanners: assessment on FDG and florbetapir PET tracers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging [Internet]. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2015;42:1447–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekine T, Burgos N, Warnock G, Huellner M, Buck A, ter Voert EEGW, et al. Multi-atlas-based attenuation correction for brain 18F-FDG PET imaging using a time-of-flight PET/MR scanner: comparison with clinical single-atlas- and CT-based attenuation correction. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2016;57:1258–1264. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.169045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mérida I, Reilhac A, Redouté J, Heckemann RA, Costes N, Hammers A. Multi-atlas attenuation correction supports full quantification of static and dynamic brain PET data in PET-MR. Phys Med Biol [Internet]. 2017;62:2834–58. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28181479. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Rezaei A, Defrise M, Bal G, Michel C, Conti M, Watson C, et al. Simultaneous reconstruction of activity and attenuation in time-of-flight PET. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet] 2012;31:2224–2233. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2012.2212719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuyts J, Bal G, Kehren F, Fenchel M, Michel C, Watson C. Completion of a truncated attenuation image from the attenuated PET emission data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet]. 2013;32:237–46. [cited 28 Aug 2017] Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6310065/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nuyts J, Dupont P, Stroobants S, Benninck R, Mortelmans L, Suetens P. Simultaneous maximum a posteriori reconstruction of attenuation and activity distributions from emission sinograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet] 1999;18:393–403. doi: 10.1109/42.774167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salomon A, Goedicke A, Schweizer B, Aach T, Schulz V. Simultaneous reconstruction of activity and attenuation for PET/MR. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet] 2011;30:804–813. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2095464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boellaard R, Hofman MBM, Hoekstra OS, Lammertsma AA. Accurate PET/MR quantification using time of flight MLAA image reconstruction. Mol Imaging Biol [Internet] 2014;16:469–477. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keereman V, Fierens Y, Broux T, De Deene Y, Lonneux M, Vandenberghe S. MRI-based attenuation correction for PET/MRI using ultrashort Echo time sequences. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2010;51:812–818. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ladefoged CN, Law I, Anazodo U, St. Lawrence K, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Catana C, et al. A multi-centre evaluation of eleven clinically feasible brain PET/MRI attenuation correction techniques using a large cohort of patients. Neuroimage [Internet] 2017;147:346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delso G, Wiesinger F, Carl M, McKinnon G, Khalighi M, ter Voert E, et al. ZTE-based clinical bone imaging for PET/MR. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2015;56:1806. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiesinger F, Sacolick LI, Menini A, Kaushik SS, Ahn S, Veit-Haibach P, et al. Zero TEMR bone imaging in the head. Magn Reson Med [Internet] 2016;75:107–114. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine T, ter Voert EEGW, Warnock G, Buck A, Huellner M, Veit-Haibach P, et al. Clinical evaluation of zero-Echo-time attenuation correction for brain 18F-FDG PET/MRI: comparison with atlas attenuation correction. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 2016;57:1927–32. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27339875. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Adam L-E, Zaers J, Ostertag H, Trojan H, Bellemann ME, Brix G. Performance evaluation of the whole-body PET scanner ECAT EXACT HR/sup +/following the IEC standard. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci [Internet] 1997;44:1172–1179. doi: 10.1109/23.596983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant AM, Deller TW, Khalighi MM, Maramraju SH, Delso G, Levin CS. NEMA NU 2-2012 performance studies for the SiPM-based ToF-PET component of the GE SIGNA PET/MR system. Med Phys [Internet] 2016;43:2334–2343. doi: 10.1118/1.4945416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tustison NJ, Cook PA, Gee JC. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging [Internet] 2011;29:1310–1320. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2046908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klauschen F, Goldman A, Barra V, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Lundervold A. Evaluation of automated brain MR image segmentation and volumetry methods. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:1310–1327. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appel L, Jonasson M, Danfors T, Nyholm D, Askmark H, Lubberink M, et al. Use of 11C-PE2I PET in differential diagnosis of Parkinsonian disorders. J. Nucl. Med. [Internet] 2015;56:234–242. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.148619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonasson M, Appel L, Engman J, Frick A, Nyholm D, Askmark H, et al. Validation of parametric methods for [11C]PE2I positron emission tomography. Neuroimage [Internet] 2013;74:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juttukonda MR, Mersereau BG, Chen Y, Su Y, Rubin BG, Benzinger TLS, et al. MR-based attenuation correction for PET/MRI neurological studies with continuous-valued attenuation coefficients for bone through a conversion from R2* to CT-Hounsfield units. Neuroimage [Internet]. 2015;112:160–8. [cited 28 Jun 2017] Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1053811915001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Izquierdo-Garcia D, Hansen AE, Forster S, Benoit D, Schachoff S, Furst S, et al. An SPM8-based approach for attenuation correction combining segmentation and nonrigid template formation: application to simultaneous PET/MR brain imaging. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2014;55:1825–1830. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.136341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poynton CB, Chen KT, Chonde DB, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Gollub RL, Gerstner ER, et al. Probabilistic atlas-based segmentation of combined T1-weighted and DUTE MRI for calculation of head attenuation maps in integrated PET/MRI scanners. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging [Internet]. 2014;4:160–71. [cited 28 Jun 2017] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24753982. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Chen Y, Rubin BG, Lee YZ. Probabilistic air segmentation and sparse regression Estiattenuation correction. Radiology [Internet] 2015;275:562–569. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J, Jian Y, Jenkins N, Behr SC, Hope TA, Larson PEZ, et al. Quantitative evaluation of atlas-based attenuation correction for brain PeT in an integrated time-of-flight PeT/Mr imaging system 1 NEURORADIOLOGY: quantitative evaluation of atlas-based attenuation correction for brain PET. Yang et al. Radiology [Internet]. 2017;284 [cited 10 Jan 2018] Available from: http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/pdf/10.1148/radiol.2017161603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Yang J, Wiesinger F, Kaushik S, Shanbhag D, Hope TA, Larson PEZ, et al. Evaluation of sinus/edge-corrected zero-echo-time–based attenuation correction in brain PET/MRI. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2017;58:1873–1879. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.188268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boellaard R, van Lingen A, Lammertsma AA. Experimental and clinical evaluation of iterative reconstruction (OSEM) in dynamic PET: quantitative characteristics and effects on kinetic modeling. J Nucl Med [Internet]. Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2001;42:808–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage [Internet]. 1996;4:153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamoto Y, Osman M, Cohade C, Marshall LT, Links JM, Kohlmyer S, et al. PET/CT: comparison of quantitative tracer uptake between germanium and CT transmission attenuation-corrected images. J Nucl Med [Internet]. Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43:1137–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visvikis D, Costa DC, Croasdale I, Lonn AHR, Bomanji J, Gacinovic S, et al. CT-based attenuation correction in the calculation of semi-quantitative indices of [18F]FDG uptake in PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging [Internet]. Springer-Verlag. 2003;30:344–353. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Juttukonda M, Su Y, Benzinger T, Rubin BG, Lee YZ, et al. Probabilistic air segmentation and sparse regression estimated pseudo CT for PET/MR attenuation correction. Radiology [Internet]. 2015;275:562–569. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of rescaling atlas and ZTE-AC maps to 68Ge-AC values. (DOCX 336 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author, João M. Sousa (joao.sousa@surgsci.uu.se), for the data used in this manuscript.