Abstract

Europe has seen an increase of women joining or sympathizing with the terrorist organization ISIS. These women are often considered victims and passive agents, but their threat should not be underestimated. Effective counter-measures are essential, especially now the so-called caliphate is in decline and many females want to return home. Exit programmes to deradicalize, disengage, reintegrate or rehabilitate are often part of a broader programme to prevent and counter violent extremism (CVE). Little is known about the effectiveness of such exit programmes, in particular in relation to female violent extremism. Drawing on municipal exit programmes in the Netherlands as a case study, the article researches how realistic evaluation can be used to measure the effectiveness of exit programmes. It also shows that the realistic evaluation method is beneficial for further theory development on the phenomenon of female violent extremism.

Keywords: Countering violent extremism (CVE), exit programmes, deradicalization, female violent extremism, realistic evaluation

Résumé

L’Europe connaît une augmentation du nombre de femmes qui rejoignent ou sympathisent avec l’organisation terroriste État islamique. Ces femmes, souvent considérées comme des victimes et des agents passifs, représentent pourtant une menace qu’il ne faudrait pas sous-estimer. Des mesures efficaces de lutte antiterroriste sont indispensables, en particulier maintenant que le « califat » autoproclamé est sur le déclin et que beaucoup de femmes parties pour le djihad cherchent à revenir. Des programmes de sortie de la radicalisation destinés à déradicaliser, désengager, réintégrer ou réhabiliter font souvent partie d’un programme plus vaste de prévention et de lutte contre l’extrémisme violent. On sait peu de choses sur l’efficacité de ces programmes de sortie, en particulier pour ce qui concerne l’extrémisme violent des femmes. À partir de l’exemple des programmes municipaux de sortie de la radicalisation mis en place aux Pays-Bas, nous cherchons dans cet article à déterminer comment l’évaluation réaliste peut être utilisée pour mesurer leur efficacité.

Mots-clés: Déradicalisation, évaluation réaliste, extrémisme violent des femmes, lutte contre l’extrémisme violent, programmes de sortie

Resumen

Europa ha visto un aumento de mujeres que se unen o simpatizan con la organización terrorista ISIS. Estas mujeres son consideradas a menudo como víctimas y agentes pasivos, pero su amenaza no debe subestimarse. Las contramedidas efectivas son esenciales, especialmente ahora que el denominado Califato está en declive y muchas mujeres desean regresar a sus hogares. Los programas de salida del radicalismo para desradicalizar, desvincularse, reintegrarse o rehabilitarse a menudo forman parte de un programa más amplio para prevenir y contrarrestar el extremismo violento. Se sabe poco sobre la efectividad de tales programas de salida del radicalismo, en particular en relación con el extremismo violento femenino. Basándose en los programas municipales de salida del radicalismo en los Países Bajos como estudio de caso, el artículo investiga cómo se puede usar la evaluación realista para medir la efectividad de los programas de salida del radicalismo.

Introduction

Since the proclamation of the so-called caliphate in June 2014, increasing numbers of women and girls have travelled to Syria and Iraq. Initially these females were thought to have a passive role in the foreign fighter phenomenon. They were portrayed as victims, groomed to marry ISIS fighters and become ‘jihadi brides’ and mothers to the ‘cubs of the caliphate’. This discourse in which women are viewed as victims has hindered effective policy against female violent extremism. Many European member states initially did not prosecute females returning from ISIS nor did they offer ‘exit programmes’ aimed at deradicalization, disengagement or reintegration (Renard and Coolsaet, 2018; Wittendorp et al., 2017).

Recent studies present a different and more disturbing picture than the discourse of females as victims. ISIS women often receive sniper training, carry Kalashnikovs and wear suicide vests; they become members of the Al-Khansaa brigade (the ISIS religious police) and are involved in propaganda and recruitment, grooming other women and girls online to travel to the so-called caliphate (AIVD, 2016a, 2016b, 2017; CODEXTER, 2016; Saltman and Smith, 2015). In short, there is an increased awareness that women play a much more active role than hitherto assumed and their threat should not be underestimated. Thus, having effective counter-measures in place to deal with female violent extremism is critical, particularly now more women are returning home since the decline of ISIS.

Empirical evidence on the effectiveness of counter-measures such as exit programmes is scarce and often disputed (Dalgaard-Nielsen, 2013; El-Said, 2012; Horgan and Braddock, 2010; Koehler, 2016). Additionally, the few evaluations that have been conducted are of exit programmes aimed at male violent extremists. Thus, we are in need of evaluations that help us gain insights into the effectiveness of exit programmes aimed at female violent extremism. What we already know is that science and practice stress the importance of tailor-made approaches to deradicalization and disengagement (El-Said, 2012; Gielen, 2017a; RAN, 2017; Schuurman and Bakker, 2016; Weggemans and De Graaf, 2017). However, tailor-made implies a different set of interventions for each case study, which cause challenges in terms of comparativeness. We are thus also in need of an evaluation method that can deal with different contextual circumstances.

Taking the Netherlands as a case study, the need for (a suitable method for) evaluation of exit programmes becomes even more clear.

With 100 female jihadists in the country and at least 80 who have joined ISIS, the Netherlands has, in relative terms, the largest number of female jihadists in Europe (AIVD, 2017).

As part of the Dutch approach municipalities are responsible for countering violent extremism (CVE), including tailor-made and multi-agency efforts to foster the deradicalization and disengagement of individuals who have travelled to join ISIS or attempted to do so (Gielen, 2015b; NCTV, 2014). While Dutch municipalities can involve the probation services, child protection services and the ‘national exit programme’ recently established in the Netherlands, they always remain responsible for the individual and the type of programme they receive. Dutch municipalities, particularly ‘priority municipalities’ (geprioriteerde gemeenten) with many foreign fighters, have been pioneering an approach since 2013 for people who have attempted to travel to a conflict zone or have returned from there. Some have chosen to adopt mainly legal and administrative measures, such as revoking passports and involving child protection services. Others have opted for a holistic approach that includes mentoring, religious counselling and psychological and psychiatric support. This makes municipalities a very logical focus and locus of research.

While a local and tailor-made approach is crucial to success, it does present some methodological challenges in terms of evaluation. For example, the Netherlands has 390 municipalities, and all social and youth care within the country has been decentralized to the municipal level. This implies that the contextual conditions that influence and affect exit programmes can differ markedly at a local level. While some municipalities have a relatively large concentration of jihadists, both women and men, and are thus more experienced in dealing with the issue, other municipalities have never dealt with extremism before. Another important contextual factor is age. Women travelling to ISIS territory or attempting to do so, are typically young, and often minors. This affects counter-measures, as punitive measures such as imprisonment are often not an option.

Realistic evaluation is particularly suited to deal with these and other challenges related to evaluating CVE (Gielen, 2015a, 2017a; Pawson and Tilley, 1997). The realistic evaluation method emphasizes the contextual factors and mechanisms that underlie interventions and lead to specific outcome patterns. Tracing these might provide insights to help answer the research question ‘what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances in exit programmes for female jihadists’.

The aim of this article is to provide a proposal as to how realistic evaluation can be applied to exit programmes. It follows the four steps of realistic evaluation. The article starts by developing hypotheses (step 1) on relevant contextual conditions and mechanisms for effective exit programmes for female jihadists. It does this by drawing on theory regarding female terrorism, exit programmes and the local Dutch approach. Second, it illustrates the types of multi-method data collection that can be used (step 2) and the relevant context, mechanism and outcome patterns that should be analysed (step 3). The potential end result is a more refined theoretical model (step 4) on what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances in exit programmes for female jihadists. Before the four steps are applied, female jihadists and exit programmes are clarified conceptually.

Definitions

For the purpose of this research a female jihadist is considered a girl or woman who has either considered (and is registered as such by the police) or attempted to travel to ISIS territory; who facilitates or recruits others for travel or marriage to jihadists; has returned from ISIS territory; or has committed acts of violent extremism. These females have a certain amount of agency in the sense that they knowingly and willingly (consider) travel to ISIS territory and recruit others to do so and have taken some kind of preparatory measures, such as marrying an ISIS fighter online, before travelling, organizing finances to be able to travel or being part of a pro-ISIS social media chat group (e.g. on WhatsApp, Telegram or some other platform). Minors taken by their parents to the so-called caliphate are not considered female jihadists.

What these women have in common is that authorities (police, municipality or others) know that they were considering attempting to travel to ISIS territory or are returning from ISIS territory. As such, authorities have undertaken measures to prevent or counter that process. Those measures can vary from revoking passports to exit programmes. Exit programmes are considered all efforts undertaken by or under the responsibility of a municipality aimed at deradicalization (changing extremist beliefs), disengagement (dissuading from violent extremist action), reintegration and rehabilitation (Horgan and Braddock, 2010; Veldhuis, 2012).

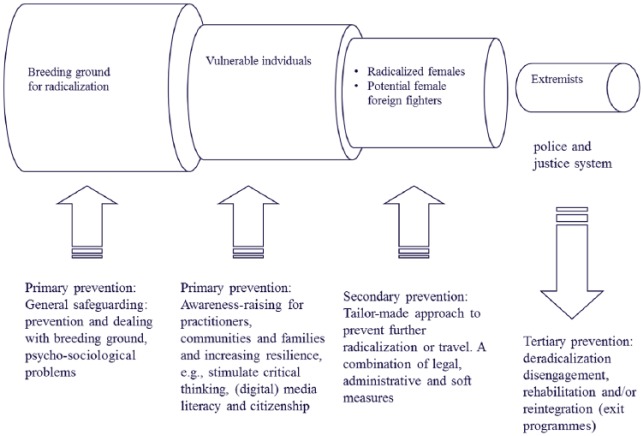

Exit programmes can be undertaken at different stages: to prevent imprisonment, during imprisonment or after imprisonment. Based on the CVE prevention classification model (Gielen, 2017a; Figure 1), ‘exit programmes’ for female jihadists fall in the secondary and tertiary category of CVE. While secondary prevention is aimed at preventing travel and (further) radicalization or extremism, tertiary prevention interventions are offered once someone has already engaged in acts of violent extremism, as is the case with female returnees. Unlike secondary prevention, tertiary prevention is offered after criminal prosecution and possible imprisonment.

Figure 1.

CVE prevention model based on Gielen (2017a, 2017b).

Theoretical model (step 1)

The first step of realistic evaluation is to develop a theoretical model for forming hypotheses on what might work, for whom and how in exit programmes for female jihadists. However, the empirical basis of the scientific literature on exit programmes is rather limited (Dalgaard-Nielsen, 2013). Those studies that are empirically based look either at voluntary exit or at government-led exit programmes, particularly in the Middle East, which is a completely different context than the European or Dutch situation. Also, studies that focus on voluntary exit or government-led exit programmes generally focus on males or a combination of males and females. There are no empirical studies on government-led exit programmes specifically targeted toward females.

Luckily, the realistic evaluation method allows a much broader definition of theory, which can also draw on related bodies of literature and include policy documents and experiences and assumptions from practitioners and policy. To hypothesize on what might work, it is crucial to gain insight into why and how female jihadists radicalize and travel, and how this process can be effectively countered. Therefore, different types of literature were included in this scoping phase. Literature on (1) processes of (de)radicalization and (dis)engagement of women involved in violent extremist organizations, (2) female jihadism and violent extremism, (3) exit programmes and (4) the Dutch municipal multi-agency approach. The rules of realistic evaluation, furthermore, allowed me to draw not only on scientific knowledge but also on my own experiences in interventions for women who had attempted to travel to Syria. I could thus draw on my practice-based knowledge as an intervention provider and as an advisor to municipalities across the Netherlands on family support and exit programmes for female foreign fighters. Pawson and Tilley (1997: 88) labelled this practical and policy experience ‘folk theory’. Applied to exit programmes for female jihadists, folk theory consists of what practitioners in the field of CVE deem to be plausible programme mechanisms and contexts. That is, ‘what element of the exit programme might generate change in females vulnerable to extremism’ and ‘under what circumstances might the programme be successful’.

Radicalization: Motivational factors and demographics

The motivations for joining and leaving violent extremist organizations can be categorized into ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors (Bjørgo, 2009). A review of the literature on female violent extremists conducted by Jacques and Taylor (2009) highlights five categories of motivations for joining an extremist organization: social, personal, idealistic, key (trigger) events and revenge. The literature in relation to females joining ISIS discerns several pull and push factors (Saltman and Smith, 2015). A key pull factor is the notion of a religious duty to move to an Islamic country (hijra) and contribute to building the so-called caliphate. Another pull factor is the notion of belonging and sisterhood and romanticized notions of the experience. Push factors emerge from the breeding ground for radicalization and include isolation, the search for identity, having a sense of belonging, a feeling that the international Muslim community is being oppressed and persecuted and aggrievement at the (perceived) lack of international action (Saltman and Smith, 2015).

My own professional experience as an intervention provider has led me to the opinion that an additional push factor is the very troubled life histories of many Dutch ISIS women. Many have experienced violence (domestic or sexual), absent parents (physically or emotionally), discrimination and racism, troubled families (multi-problem/broken homes) and a general vulnerability. These observations are supported by a Dutch study on ISIS women (Noor, 2016) and a study by the Dutch police that analysed the histories of foreign fighters (male and female) and concluded that in 60% of the cases psycho-sociological problems played a role and in 20% of the cases psychiatric problems were a factor (Weenink, 2015). The Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service has also reported some specific characteristics of the women joining ISIS. They are generally between 15 and 30 years of age (with most between ages 16 and 20); and though they have various ethnic backgrounds, relatively many are converts to Islam (AIVD, 2017).

Recruitment

Jacques and Taylor (2008, 2009) found that some women had joined terrorist organizations either voluntarily or were recruited and were prepared to commit violent extremists acts. Recruitment can be proactive in the sense that vulnerable women are actively groomed, or it may be more reactive in that recruiters do not act until the women show an interest. Other recruitment influences mentioned in the literature are peer pressure within friend and family networks and online chat groups, love (marriage, a boyfriend) and force and exploitation (Jacques and Taylor, 2009). The Dutch National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism has also stressed the role of social media, claiming that social media is a catalyst for recruitment (NCTV, 2016). My own professional experience corroborates the role played by peers in recruitment. In my experience, the females who joined or attempted to join ISIS always had an existing relationship with other peers (family or friends) who were already involved in the jihadist network, either locally within their own municipality or in a neighbouring municipality, or globally (in Syria). These relationships were further enhanced by regular contact via social media (particularly Facebook, Instagram and Twitter) and the dark web, such as encrypted communication platforms like pro-ISIS Telegram groups. The recruiters fed into the previously mentioned vulnerabilities of these girls and women, playing into them with propaganda corresponding to the various push and pull factors.

Roles and gender

One of the most significant advantages held by female violent extremists is that the threat they pose often goes unrecognized or is downplayed. As a consequence, they are highly underestimated and effective (Cunningham, 2007: 123). Throughout history women have played various roles in violent extremist movements (De Graaf, 2012). In a literature review of female terrorism, Jacques and Taylor (2009) discerned six roles: sympathizers, spies, warriors, warrior leaders, dominant forces and suicide bombers. As noted, there has been a tendency to downplay the threat posed by ISIS women, portraying them as ‘jihadi brides’, mothers or victims. Research, however, has found the roles played by female jihadists to vary, from facilitating (mother and wife), to recruitment, to active or passive combatants in which women receive sniper training, wear suicide vests and carry Kalashnikov rifles (AIVD, 2016a; Saltman and Smith, 2015). Recent accounts suggest that women are starting to put their training to use as active combatants. Reports from Mosul (Moore, 2017) and Libya observe women being used as suicide bombers. Last year the French police arrested three women with gas canisters in their car. The police claimed that the women were radicalized, had pledged allegiance to ISIS and were planning a terrorist attack on the Gare du Lyon train station (Verschuren, 2016). The more active role of women who sympathize with ISIS or live in ISIS territory fits with the ideological and rhetorical shift that ISIS seems to have effected on the role of women (Winter and Margolin, 2017).

Motivation for exit

As noted, motivations for joining a violent extremist organization can be understood as push and pull factors. The same distinction can be applied to motivations for leaving violent extremist organizations. Push factors for exit are dissatisfaction with the extremist group members, its leaders or the ideology. Pull factors consist of positive alternatives, such as wanting a ‘normal’ life or having family obligations to fulfil, becoming a parent, for example, or having to care for a sick relative (Barrelle, 2015; Bjørgo and Horgan, 2009). Demant et al. (2008) argued that while these push and pull factors are indicative of a direction (moving away or toward) they do not illuminate the content of exit. Demant et al. (2008) distinguished three content factors for exit. The first is the ideological factor and revolves around disillusionment with the ideology, such as realization that a sustainable Islamic State is not feasible. Social factors include a sense of dissatisfaction with extremist peers or the extremist group or movement. Practical factors revolve around the personal life situation, such as feeling isolated, stigmatized or externally pressured to participate in the extremist group.

Exit programmes

As previously discussed there is very little empirical evidence on exit programmes. Based on the limited scientific and policy theoretical literature and the few empirical studies that have been conducted, some important lessons can be drawn. El-Said (2012) reviewed several exit programmes around the globe and concluded that exit programmes must be tailor-made and take into account the contextual factors of each country, including culture, traditions, history and laws. The Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN), set up by the European Commission with more than 2000 practitioners working in CVE, has made a collection of approaches and inspiring practices in CVE (RAN, 2017), which also underline that exit programmes should be tailor-made. It furthermore advises that exit programmes take a long-term approach and consist of multiple interventions aimed at the individual level via mentoring, psychological counselling, theological guidance and practical interventions such as provision of schooling and housing, as well as interventions aimed at the family level, such as family support. Furthermore, the RAN Collection underlines that exit programmes require a multi-agency approach, properly trained staff knowledgeable on the issue of violent extremism and specific competences in terms of, for example, relationship formation and communication skills. These elements are also acknowledged in the empirical pilot study of a deradicalization programme conducted by Hallich and Doosje (2017). These authors emphasized that successful exit depends not only on ‘best practices’ but also on ‘best people’. Establishing trust-based relationships between the intervention provider, the female and her family and being able to provide support in a multi-agency setting, are crucial elements for exit programme success.

Demant et al. (2008) similarly stressed the importance of an integral approach to deradicalization and disengagement. In their opinion, exit programmes for jihadists focus too much on normative factors, concentrating on theological and ideological issues, and as a consequence overlook affective factors such as the family and peer network (Demant et al., 2008: 181). The Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service as well as the Office of the National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism (NCTV, 2016) report that most returnees remain active in the jihadist network upon return, because they are welcomed by the jihadist network with open arms and sucked back into the network. Creating an alternative network both online and offline is essential to offer an alternative to the grooming of the extremist network. Particularly because disengagement often leads to takfir (excommunication) and the loss of friends and sisterhood. Demant et al. (2008) argue that European exit programmes would benefit from a more comprehensive focus, dealing with all exit factors – normative, affective and practical – without favouring one factor over the others. This argument is also made in more recent studies on exit programmes (Koehler, 2016; Weggemans and De Graaf, 2017). The AIVD (2016a) has stated that single interventions, such as only revoking a passport, are ineffective, as individuals are likely to attempt to travel to ISIS territory a second and third time, even without their passport. In sum, the success of an exit programme is dependent on the extent to which the programme is integral and holistic and addresses ideological, social and practical issues.

The Dutch local approach

One of the cornerstones of the Dutch CVE approach is involvement of the local level. As noted, municipalities in the Netherlands are responsible for their own CVE programmes. These may consist of community engagement, awareness raising, educating young people and also case management of individuals who have become radicalized or (violent) extremist (Gielen, 2015b; NCTV, 2014). While the NCTV (2014) and the Association of Dutch Municipalities (Vereniging Nederlandse Gemeenten) have recommended that municipalities develop CVE programmes and set up protocols for multi-agency case management (Gielen, 2015b), it is not compulsory. Initially only the larger cities in the Netherlands did so, such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Utrecht. Some of these cities set up their programmes relatively early, in the aftermath of the assassination of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004. These larger cities thus have a relatively longer history of experience with CVE programmes and case management than the many smaller municipalities that initiated programmes later. Indeed, some municipalities did not feel the need to implement a CVE programme or set up multi-agency case management protocols, because they had not yet been confronted with cases of violent extremism. As a consequence, many municipalities were overwhelmed when young men and women, and sometimes whole families, left to join ISIS. These municipalities then had to start from scratch, developing and implementing their CVE programme and protocols for case management for their residents who were radicalizing or turning to violent extremism. Recent research by the Dutch Inspectorate for Safety and Justice (Inspectie voor Veiligheid en Justitie, 2017) concluded that 64% of the small and 30% of the mid-sized municipalities still did not have a CVE programme in place. This raises the question of whether having a CVE programme from the outset positively or negatively influences the outcome of municipal actions in exit programmes.

Case management of extremists and potential extremists is done in a multi-agency setting. The municipality works with the police, the public prosecution office, child protection services, the probation services, mental healthcare services and NCTV to do a risk assessment and decide on the best course of action. This may consist of legal and administrative instruments as well as ‘soft’ measures, such as ideological and psychological counselling, family support, practical support with housing and a job, help in breaking contact with the former extremist network to prevent further grooming, a social media ban to prevent further grooming and involvement of child protection services to enforce necessary changes in troubled family situations (Gielen, 2015b; NCTV, 2014).

Hypotheses on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes for exit programmes

These theoretical and practice-based notions on motivation, demographics, roles, recruitment, exit programmes and the local approach help us to discern relevant contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. These can be used in building our theoretical model, first by describing relevant Cs, Ms and Os, unconfigured, after which a model can be developed proposing how they interact and work in configuration.

Contexts

Social programmes such as CVE are highly contextual. Contexts influence how programmes work, as the conditions in which programmes are introduced are relevant to how the programmes are implemented and their outcomes. Features of contextual significance may relate not only to a physical space (e.g. a prison) or a geographical location (e.g. Amsterdam) but also to the target audience (e.g. demographics and motivational factors of extremists), the individual capacities of key actors (e.g. the training or experience level of the intervention provider), the interpersonal relationships between intervention providers and the extremist and the broader institutional setting (e.g. the infrastructure of the municipality) (Pawson and Tilley, 1997: 69; 2004: 4). Box 1 lists some of the contextual conditions of potential relevance to this research.

Box 1.

Hypothetical contextual conditions for exit programmes.

| Demographic and motivational factors • Age (minor or not) • Socio-economic position • Nationality • Stopped or returned? • Process of radicalization: push and pull factors • Psycho-sociological issues (e.g. broken homes, multi-problem family)? • Psychiatric problems (e.g. limited cognitive abilities, post-traumatic stress syndrome)? Gender • Perspective of female self (strong and independent or submissive) • Roles and relationships within networks of family and peers • Roles and relationships within jihadi network (e.g. marriage within a jihadi network) Experience of the municipality • Previous experiences with jihadism? • Presence of a multi-agency meeting (case discussions)? • Existence of CVE policy? • Awareness training for practitioners? Institutional setting municipality • Specific activities for women and girls (e.g. sports and community centre)? • Religious infrastructure: Dutch spoken? Traditional or Salafi? Space for teens and adolescents? Quality of the municipal multi-agency approach • Is the municipality in charge? • Was the approach set up before or after the travel of female jihadist(s)? • Frequency of case meetings (e.g. weekly, monthly, quarterly)? • Involvement of the National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism (NCTV) in multi-agency approach? • Involvement of multi-agency partners such as police, public prosecution office, intelligence services, child protection services, youth care, a social work team and mental health carers? • Have partners in the multi-agency approach received in-depth training? |

Mechanisms

Like any CVE programme or intervention, exit programmes consist of different measures. Mechanisms are not the activities of a programme itself, such as family support or theological guidance. Rather, mechanisms are the aspects of those different measures that might cause change and effect (Pawson and Tilley, 1997: 66; 2004: 6). Mechanisms can be understood as theories of change: the set of causal assumptions that implicitly or explicitly underlie a programme or intervention (Weiss, 1995). The list below sets out a preliminary overview of possible exit interventions that can induce specific mechanisms (Gielen, 2015a, 2017a; RAN, 2014):

Mentoring can promote and enhance empathy, confidence, relationship skills, responsibility and the ability to reflect on one’s actions and life history.

Religious and ideological support can reduce the attraction of the extremist narrative.

Practical support in establishing a stable environment and daily routine can foster and sustain reintegration and rehabilitation.

Psychological support and counselling can address struggles with existential questions, mental health issues, making sense of things and finding a meaningful place in society.

Family support can help parents identify warning signals and stimulate positive parenting styles, reducing the attraction of extremist groups and enhancing protective factors.

Administrative measures can take away the necessary prerequisites for travel (e.g. passport).

Legal measures can prevent a person from travelling by taking away their freedom (imprisonment) or invoke specific release conditions prohibiting contact with the former extremist network (e.g. a social media ban).

Outcomes

Outcome patterns consist of the positive and negative (unintended) consequences of programmes, which are a result of the activation of different mechanisms in different contexts (Pawson and Tilley, 1997: 217). Though measuring outcomes is often considered challenging in CVE, the focus of this research helps us to formulate measurable indicators. The first indicator for a positive outcome of an exit programme is whether the female in question has attempted to travel again after being stopped a first time. In addition to that indicator, Barrelle’s (2015) model can be used to assess the extent that someone has become disengaged. Her five-domain, three-level model of disengagement is called the Pro-Integration Model (Barrelle, 2015). The five domains concern social relations, coping, identity, ideology and action orientation. In each domain, three forms of social engagement are possible: minimal, cautious and positive. For example, in the domain of social relations, someone with minimal social engagement will have no positive interactions with people from the (non-extremist) ‘out-group’ and no or limited engagement with society (only that which is strictly necessary). This person will mainly have contacts with the (extremist) ‘in-group’. People with cautious social engagement levels are on a journey of disengaging from the extremist group and in the process of restoring ties with their family and former (non-extremist) peer network. These interactions can sometimes still prove awkward and uncomfortable. Positive social engagement is the best possible outcome of a disengagement process, with positive relationships with family members and others in the non-extremist network. Participants are able to interact in a positive or neutral way with people who previously belonged to the ‘out-group’. There are no longer ties and relationships with people from the former extremist group (Barrelle, 2015: 138–139).

The end result of this first phase of realistic evaluation is a theoretical model that highlights why and how female jihadists radicalize and addresses possible relevant contexts, mechanisms and outcomes to counter the process, while hypothesizing on how these contexts, mechanisms and outcomes work in configuration. Thus, how might the contextual conditions and mechanisms of exit strategies for female jihadists lead to specific outcome patterns?

A hypothesized C-M-O configuration might look as follows:

Exit programmes can be offered to women who have attempted to travel to ISIS (C1). They can be offered by the municipality (C2) in a multi-agency setting (C3). It is important that the exit programme be tailor-made (C4) and draw on the specific personal circumstances (C5) and motivational factors (C6) of the girl or woman concerned. Exit programmes should at least entail individual mentoring to increase relationship skills, empathy, confidence, responsibility and the ability to reflect on one’s actions and life history (M1). They should include multiple elements: conversation techniques such as discussion, dialogue and negotiation to reduce prejudices and stereotyping and stimulate critical thinking (M2); social and economic support to establish a stable environment and a daily routine to foster and sustain reintegration and rehabilitation (M3); religious or ideological counselling to reduce the attraction of the extremist narrative (M4); psychological support and counselling to deal with existential questions, make sense of things and find a meaningful place in society (M5); and family support to enhance protective factors (M6). In the short term, an exit programme is aimed at preventing a second travel attempt (O1). The ultimate aim of the exit programme is deradicalization (O2) or disengagement (O3).

Multi-method data collection and analysis (steps 2 and 3)

The realistic evaluation method does not position itself as positivist or interpretivist, and it does not prefer one data collection method over another. It does, however, stipulate that multiple methods of data collection be used. Evaluation of exit programmes for women could make use the following data collection methods:

a questionnaire (conducted face-to-face) among the municipal case managers, focusing on relevant contexts, mechanisms and outcomes in each case;

desk research, involving police and municipal registries or child protection services files on cases representing the abovementioned contexts, mechanisms and outcomes;

interviews with stakeholders involved in the exit programme (e.g. social workers and intervention providers); and

interviews with or questionnaires among the women who have participated in a municipal exit programme.

While participant observation would be perfectly suited to gain detailed insight in for example conversation techniques, it is most likely also the hardest to achieve. It is already difficult enough for the intervention provider to gain the trust of radicalized individuals, let alone with researchers present. At the same time issues of practicality or financing should not be leading in the choice of research methods. The decision on which multiple methods of data collection to choose for the evaluation research should always be based on how each data collection method contributes to the explorative question of what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances.

The data that need to be acquired would be concentrated on the abovementioned contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Which interventions and underlying mechanisms led to the successful or unsuccessful disengagement of this particular young female jihadist? What contextual factors made it possible to activate those mechanisms? To what extent did the outcomes fit or differ from the theoretical model developed during the first phase of the realistic evaluation? Data collection should also look at cases of women who did not receive any form of programme support but, for example, only had their passport revoked or only received a criminal sentence, as they can serve as a control group. Cases from exit programmes for female jihadists in other Dutch municipalities should also be sought. However, if one decides to make use of a control group or a comparison between municipalities, one must not fall into the experimentalist trap to compare ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ in the sense that some programmes do work and others do not. Rather, realistic evaluation should concern itself with the ‘make-up’ of the interventions and respondents to address the question why some programmes work better for some than for others (Pawson and Tilley, 1997: 40).

Each case should thus be analysed in terms of relevant contexts, mechanisms and outcome patterns and how they worked in configuration. Below is an example of a real-life case and its analysis in a realist fashion.

A minor (C1) with psycho-sociological problems (C2) and poor family relations (C3) from a small municipality in the Netherlands (C3) with no experience with CVE (C4), no CVE policy in place (C5) and no multi-agency approach in place (C6) attempted to travel to ISIS territory but was stopped at the Turkish border (C7). Her plan was to live in the so-called caliphate with her husband, whom she had previously married online (C8). She was recruited by some of her friends in the Netherlands (C9) who were friends with somebody who had joined ISIS a year earlier. Through her friends she also joined a pro-ISIS WhatsApp chat group (C9) in which Dutch girls and women spoke about their hatred of the Netherlands and their desire to travel to Syria. After she was stopped, she was not prosecuted (C10) because she was a minor, but instead was handed over to a case worker from the Dutch youth services (C11). As she and her parents cooperated voluntarily (C12), the Dutch child protection services were not involved (C13).

Her case was discussed in a multi-agency meeting (C14) which was set up after her travel (C15). At this meeting the municipality, the public prosecution office, the police, the intelligence services and the youth care services set out a multi-agency approach (C16). It was decided that she and her family needed specialist family support. The minor was to follow an exit programme and her passport was to be temporarily revoked. As no national exit programme existed at the time, the programme had to be tailor-made. The programme was completely voluntary, and tailored to her needs (C17).

The girl in question had indicated that she really wanted to go back to school, but her local school would not have her back due to the social unrest that her travel had caused within the school and the broader community. Not going to school caused her to be isolated and more vulnerable to extremists (C18), so the first intervention as part of her exit programme was getting her back into school in order to establish a stable environment and a daily routine (M1).

Initially her mobile phone was confiscated by the police for investigation. But when she went back to school she also got her smartphone back. Within 48 hours, her jihadist friends within ISIS in Syria and in the chat group started grooming her again, telling her that she should attempt to travel a second time. Together, her exit workers and mother decided to provide her with a new sim card and institute a social media ban for several months to create distance between her and the jihadist network and make her less vulnerable to grooming (M2).

During mentoring she shared her religious questions. It turned out that her knowledge of Salafi jihadism, but also on Islam in general, was very limited (C19). In fact, she did not know the difference between Sunni and Shia. As a consequence, it was not necessary to provide in-depth ideological and religious counselling in order to counter the extremist narrative. Rather, it was important to help her gain general knowledge about Islam to make her less vulnerable to extremist interpretations (M3), something her biological mother, grandfather and stepfather could provide. She also received targeted mentoring to strengthen her self-reflection abilities, as she could not properly explain why she felt the need to travel (M4).

However, it became apparent that as long as she was living in a troubled home situation (C4), she would not be able to develop individually, as she did not feel safe doing so because her biological mother and foster parents constantly argued. This issue needed to be resolved. As the biological and foster parents initially refused to sit in the same room together, this could be realized only under threat of involvement of child protection services. Getting family members to stop arguing and start parenting together in a positive way was essential to reduce the attractiveness of travel to ISIS (M5). In the words of the girl, ‘All my parents did was fight with each other, to the extent I just thought to myself, nobody would even miss me if I travelled to ISIS.’ It was not until after this intervention that the mentoring started taking effect.

She now became able to write a short life story about the issues of the past, trigger events and her motivation for travel (O1). This seemed a crucial development, because for the previous 10 months, the only explanations she could give were the narratives that were used to recruit her. Creating her own narrative gave her a sense of agency and control (O2). Attempting to join ISIS was no longer something that had just happened to her. She gained insight into her own radicalization process and as such recognized what situations she would be better off avoiding and when to ask for help (O3).

While the psychological assessment revealed no personality disorders or other issues (C20), the girl did display low mood at times, had little energy and was often sick (C21). A doctor’s visit and blood test showed a serious vitamin D deficiency, because she was veiled (C22). Vitamin D shots and supplements helped her gain the energy so essential for her reintegration and rehabilitation (M6).

Another crucial element turned out to be her social network. Her social network had consisted of jihadists; the sisters in the ISIS chat group had become her friends (C23). As she was no longer allowed to contact them and they could not contact her because of her new sim card, her social network became very limited, which frustrated her immensely: ‘I have lost all my friends, but I don’t have any new ones (yet).’ This was perhaps the hardest part of the exit programme, because a new social network cannot be formed overnight. The combination of a new class at her old school, a part-time job at the local supermarket and joining the school debate team helped her develop a new and positive social network, reducing the attractiveness of her former jihadist network (M7).

The young woman in the above case participated in the exit programme for a year and a half, after which her progress was evaluated with her, her family and the municipality using Barrelle’s (2015) disengagement model. There had been no new travel attempts to ISIS (O4) and the evaluation showed that she had fully disengaged (O5), based on positive levels of social engagement on all five domains described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of social engagement in case study based on Barrelle’s (2015) Pro-Integration Model.

| Domain | Positive levels of societal engagement |

|---|---|

| Social relations | Positive relationship with family, friendly relationships with non-Muslims and no contact with former extremist network |

| Coping | Able to address personal issues, understanding of push and pull factors and trigger events for travel and able to undertake meaningful activities by going back to school and getting a part-time job |

| Identity | No identification with extremist group, proper sense of self and life history, no longer categorizes in ‘us’ and ‘them’ and no longer uses extremist recruitment narratives for explaining why she wanted to join ISIS |

| Ideology | Does not hold radical views, respects other (world)views, even gave her intervention provider a Christmas card, focuses on moderate law school and scholars |

| Action orientation | Does not consider violence a legitimate method, no longer wants to travel to ISIS, but focuses on her future in the Netherlands and positive action and participation by other means (e.g. joining the debate team at school) |

Conclusion: Refined programme theory (step 4) and reflection

The idea of realistic evaluation research on exit programmes for females is that many more cases are studied and analysed in the abovementioned fashion. The end result would then be a refined programme theory, answering the question ‘what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances in exit programmes for female jihadists’. The aim is not to make general statements in terms of ‘X does not work, but Y does’, but rather to contribute to a more refined programme theory on exit programmes for females that provides insight into relevant contextual conditions and mechanisms for exit programmes.

We cannot infer a more refined programme theory based on the analysis of the single case above. However the experience with this case corresponds with my experience in other cases and issues that are highlighted in the previously mentioned literature on female violent extremism and exit programmes. The development of a proposal for how to conduct a realistic evaluation for exit programmes is helpful in developing additional hypotheses on female violent extremism and exit programmes which in turn can be used for empirical testing:

Recruitment is done through ‘glocal’ jihadi networks with social media as a catalyst. There are usually existing relationships with peers involved in the jihadist network, either locally or globally (hence ‘glocal’). Recruiters feed into the vulnerabilities of potential recruits, and activate a variety of push and pull factors.

Exit requires a long-term and holistic approach that takes into account the push and pull factors, combining multiple interventions that activate different mechanisms. For example, such a programme might entail mentoring, practical support, family support, physical and psychological assessment and counselling and theological and ideological guidance.

The sequence of interventions in the exit programme is important and must be tailored to the needs of the individual. Practical interventions can help participants gain sufficient trust to move forward with other interventions. Creating a safe and stable family environment can be an important precondition to mentoring and learning self-reflection.

Creating an alternative social network is essential to compensate for loss of friends or sisterhood.

The success of an exit programme does not seem to be dependent on the size or experience of a municipality. Rather, it seems determined more by the extent to which the exit programme is integral and holistic and addresses normative, affective and practical issues.

The success of an exit programme is also dependent on the intervention provider. The ability to establish a trust-based relationship with the individual and her family and operate in a multi-agency setting is imperative.

While a soft approach seems more promising, legal and administrative instruments can be helpful in creating the right conditions for exit. Specific conditions are no contact with the former extremist network to prevent further grooming, a social media ban to prevent further grooming and involvement of child protection services to enforce necessary changes in troubled home situations.

Reflection

This article has provided a proposal for how to conduct a realistic evaluation to evaluate exit programmes for jihadist women. It thus provides a methodological framework and heuristics that can be used in future evaluation research. Applying realistic evaluation to a domain as complex as violent extremism and exit programmes does pose challenges. The C-M-O analysis of one real-life case illustrated the multitude of possible contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. In a full-fledged evaluation, multiple cases need to be analysed, to enable us to highlight the most important and relevant C-M-O configurations.

While this article focused on the situation in the Netherlands, many of the highlighted contextual factors, mechanisms and outcome patterns can be applied in evaluation research on exit programmes in other countries. The end result will be a refined programme theory that answers the question ‘what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances in exit programmes for female jihadists’. Another outcome will be contributions to scientific theory on why and how women are radicalized and recruited, because their contexts have been analysed as part of the research. For example, understanding the role of factors like the troubled life histories of many of these girls, their online chat group behaviour and their different roles (not merely as ‘jihadi brides’) helps us to better understand the female foreign fighter phenomenon.

Author biography

Amy-Jane Gielen is an honours graduate in Political Science and a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. She will be defending her PhD ‘Cutting through Complexity. Evaluating Countering Violent Extremism’ in the Fall of 2018. She has worked in the field of CVE for over a decade.

Footnotes

Funding: This research has been made possible with the support of A.G. Advies B.V. and the University of Amsterdam.

References

- AIVD (2016. a) Life with ISIS: The Myth Unravelled. The Hague: AIVD; Available at: https://english.aivd.nl/publications/publications/2016/01/15/publication-life-with-isis-the-myth-unvravelled [Google Scholar]

- AIVD (2016. b) Annual Report 2015: A Range of Threats to the Netherlands. The Hague: AIVD; Available at: https://english.aivd.nl/publications/annual-report/2016/05/26/annual-report-2015-aivd [Google Scholar]

- AIVD (2017) Jihadistische vrouwen, een niet te onderschatten dreiging. 17 November The Hague: AIVD; Available at: www.aivd.nl/publicaties/publicaties/2017/11/17/jihadistische-vrouwen [Google Scholar]

- Barrelle K. (2015) Pro-integration: Disengagement from and life after extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 7(2): 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørgo T. (2009) Processes of disengagement from violent groups of extreme right. In: Bjørgo T, Horgan J. (eds) Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørgo T, Horgan J. (eds) (2009) Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- CODEXTER (Committee of Experts on Terrorism) (2016) The Roles of Women in Daesh. Discussion Paper, 26 October. Strasbourg: CODEXTER. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KJ. (2007) Countering female terrorism, studies in conflict and terrorism. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 30(2): 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard-Nielsen A. (2013) Promoting exit from violent extremism: Themes and approaches. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 36(2): 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf B. (2012) Gevaarlijke vrouwen. Tien militante vrouwen in het vizier. Amsterdam: Boom. [Google Scholar]

- Demant F, Slootman M, Buijs F, Tillie J. (2008) Decline and Disengagement: An Analysis of Processes of Deradicalisation. Amsterdam: IMES. [Google Scholar]

- El-Said H. (2012) De-radicalising Islamists: Programmes and Their Impact in Muslim Majority States. London: ICSR. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen A-J. (2015. a) Supporting families of foreign fighters. A realistic approach for measuring the effectiveness. Journal for Deradicalization 2: 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen A-J. (2015. b) Rol gemeenten in integrale aanpak radicalisering. 2 June Den Haag: VNG. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen A-J. (2017. a) Countering violent extremism: A realist approach for assessing what works, for whom, in what circumstances and how? Terrorism and Political Violence. Epub ahead of print 3 May 2017. DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2017.1313736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen A-J. (2017. b) Evaluating countering violent extremism. In: Colaert L. (ed.) ‘De-radicalisation’. Scientific Insights for Policy. Brussels: Flemish Peace Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hallich B, Doosje B. (2017) DIAMANT-plus: een methodiek voor de-radicalisering en vergroting van weerbaarheid tegen extremistische invloeden. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan J, Braddock K. (2010) Rehabilitating the terrorists? Challenges in assessing the effectiveness of de-radicalization programs,. Terrorism and Political Violence 22(2): 267–291. [Google Scholar]

- Inspectie voor Veiligheid en Justitie (2017) Evaluatie van het actieplan integrale aanpak jihadisme. 15 September Den Haag: Ministerie voor Veiligheid en Justitie; Available at: www.inspectievenj.nl/Publicaties/rapporten/2017/09/06/evaluatie-van-het-actieprogramma-integrale-aanpak-jihadisme?_sp=05f048cb-4bde-44ca-afea-da8ad2dd1cfa.1507197104559 [Google Scholar]

- Jacques K, Taylor PJ. (2008) Male and female suicide bombers: Different sexes, different reasons? Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 31(4): 304–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques K, Taylor PJ. (2009) Female terrorism: A review. Terrorism and Political Violence 21(3): 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler D. (2016) Understanding Deradicalization. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. (2017) ISIS unleashes dozens of female suicide bombers in battle for Mosul. Newsweek, 5 July. [Google Scholar]

- NCTV (2014) Handreiking aanpak radicalisering en terrorisme op lokaal niveau. 21 January Den Haag: NCTV; Available at: www.nctv.nl/onderwerpen/tb/Tools/Handreiking-aanpak-radicalisering-en-terrorismebestrijding-op-lokaal-niveau/ [Google Scholar]

- NCTV (2016) Samenvatting ‘De jihad beëindigd ? 24 teruggekeerde Syriëgangers in beeld’. 21 January Den Haag: NCTV; Available at: www.nctv.nl/binaries/samenvatting-jihad-beeindigd-def_tcm31-32539.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Noor S. (2016) Vrouwelijke ISIS-gangers: waarom gaan ze? Den Haag: Kennisplatform Integratie en Samenleving; Available at: www.kis.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Publicaties/vrouwelijke-isis-gangers.pdf [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke LA. (2009) What’s special about female suicide terrorism? Security Studies 18(4): 681–718. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Tilley N. (1997) Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Tilley N. (2004) Realist Evaluation. Available at: www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf

- RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network) (2014) RAN Collection. Approaches, Lessons Learned and Best Practices, 1st edn. Brussels: RAN; Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-best-practices/index_en.htm [Google Scholar]

- RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network) (2017) RAN Collection. Approaches and Best Practices, 4th edn. Brussels: RAN; Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-best-practices/docs/ran_collection-approaches_and_practices_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Renard T, Coolsaet R. (eds) (2018) Returnees: Who Are They, Why Are They (Not) Coming Back and How Should We Deal With Them? Assessing Policies on Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, Egmont Paper 101, February. Brussels: Egmont Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Saltman EM, Smith M. (2015) Till Martyrdom Do Us Part. Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue; Available at: www.strategicdialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Till_Martyrdom_Do_Us_Part_Gender_and_the_ISIS_Phenomenon.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman B, Bakker E. (2016) Reintegrating jihadist extremists: Evaluating a Dutch initiative, 2013–2014. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 8(1): 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis T. (2012) Designing Rehabilitation and Reintegration Programmes for Violent Extremist Offenders: A Realist Approach. The Hague: ICCT. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuren E. (2016) Gearresteerde vrouwen Parijs wilden aanslag plegen,. NRC Handelsblad, 9 September Available at: www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2016/09/09/verdachte-van-verijdelde-aanslag-notre-dame-zwoer-trouw-aan-is-a1520513

- Weenink A. (2015) Behavioral problems and disorders among radicals in police files. Perspectives on Terrorism 9(2). Available at: www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/416/html [Google Scholar]

- Weggemans D, De Graaf B. (2017) Reintegrating Jihadist Extremist Detainees: Helping Extremist Offenders Back into Society. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CH. (1995) Evaluation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Winter C, Margolin D. (2017) The Mujahidat dilemma: Female combatants and the Islamic State. CTC Sentinel, August, pp. 23–26. Available at: https://ctc.usma.edu/v2/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CTC-Sentinel_Vol10Iss7–9.pdf

- Wittendorp S, de Bont R, van Zuijdewijn J, Bakker E. (2017) Beleidsdomein aanpak jihadisme. Een vergelijking tussen Nederland, België, Denemarken, Duitsland, Frankrijk, het VK en de VS. Leiden: Universiteit Leiden; Available at: www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/governance-and-global-affairs/isga/rapport_beleidsdomein-aanpak-jihadisme_1.pdf [Google Scholar]