Abstract

Background

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM) are at disproportionate risk for HIV infection. Parent-adolescent communication about sex, particularly mother-adolescent communication, protects against adolescent sexual risk behavior. However, it is unclear whether these findings generalize to YMSM.

Purpose

The current study used the theory of planned behavior as a framework to examine how YMSM perceptions of parent-adolescent communication about condoms are associated with determinants of condom use and condomless anal sex among YMSM.

Method

YMSM ages 14–18 (M = 16.55) completed an online survey (n = 838). Associations between several domains of parent-adolescent communication about condoms (i.e., frequency and specificity, quality, and negative emotionality) and condom-related attitudes, norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions, as well as instances of condomless anal intercourse (CAI), were examined with structural equation modeling.

Results

Multiple facets of mother-adolescent communication were associated with attitudes about condoms, subjective norms for condom use, perceived behavioral control, intentions to use condoms, and indirectly, instances of CAI. Father communication was not associated with determinants of condom use behavior.

Conclusions

Parent-adolescent communication about condoms is associated with determinants of condom use behavior among YMSM, and mother communication exerted an indirect influence on HIV-related sexual risk behaviors. Interventions designed to enhance parent- adolescent communication about condoms could prove efficacious in reducing HIV infections among YMSM.

Keywords: Adolescent sexual risk, Condom use, Men who have sex with men, Parent-adolescent communication, Theory of planned behavior

Mother-adolescent communication about sex is associated with theoretical determinants of condom use and indirectly predicts HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men.

Introduction

Men who have sex with men in the USA continue to be disproportionately burdened by the HIV epidemic. Approximately two-thirds of the roughly 50,000 new HIV infections in the USA each year are among men who have sex with men [1], and young men who have sex with men (YMSM) ages 13–24 are the most severely affected of this group [2]. Among adolescents ages 13–19, male-to-male sexual contact accounts for 93% of new HIV infections each year [3]. Prevalence of HIV among YMSM is extremely high, and researchers have estimated that 7.2%–12.6% of YMSM ages 15–24 are infected with HIV [4–6]. Black/African American YMSM are at particular risk for HIV infection, with prevalence as high as 16.5% [5]. Despite the severity of the current HIV epidemic among YMSM, no effective interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among adolescent YMSM have been published [7, 8]. Moreover, new HIV-prevention technologies, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, are challenging for adolescents to access, given that they have less autonomy over their healthcare than adults. Indeed, even among young adult men who have sex with men ages 18–24 from 20 U.S. cities, only 2.7% reported taking pre-exposure prophylasix in the past year [9]. Thus, increasing consistent condom use must remain a central component of HIV prevention for teenage YMSM.

Parent-adolescent communication about sex is a promising avenue for increasing adolescent condom use and reducing sexual risk behaviors. However, very little research has examined parent-adolescent communication about sex among YMSM, and existing studies of parent-adolescent communication about sex typically do not measure sexual orientation. Among adolescents generally, most parents report they have talked with their adolescent about sexual topics [10–12], and parents typically address a wide range of sexual topics throughout these discussions, including sexually transmitted diseases, HIV and AIDS, and methods of contraception [10, 13, 14]. A meta-analysis of 34 studies pooling data from 15,046 adolescents found parent-adolescent communication about sex is associated with increased condom use among adolescents [15]. Across studies, the association between parent-adolescent communication about sex and condom use had a significant and small effect size for all adolescents. While all adolescents evidenced higher condom use if they reported more communication about sex, this effect size was larger among female adolescents than male adolescents. Mother-adolescent communication about sex was associated with condom use while father-adolescent communication was not.

Previous findings with presumably heterosexual adolescents might not generalize to YMSM because of population-specific family dynamics, and very little is known about how parent-adolescent communication functions within families of YMSM. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents’ relationships with parents are uniquely affected by their sexual minority status, including parental rejection of sexual orientation and coming out to parents about their orientation [16, 17]. Our team previously conducted the only known quantitative study of perceptions of parent-adolescent communication about sex and sexual behaviors among YMSM [18]. All YMSM in this prior study, which used a separate dataset from the current study, had a nonheterosexual identity (e.g., gay), and whether their parents knew about their sexual orientation moderated associations between frequency of parent-adolescent communication about sex and sexual risk behaviors. Specifically, more frequent communication about sex was associated with increased condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with male partners, but only among YMSM whose parents knew they were gay or bisexual. Mechanisms underlying this finding were not tested in the study, but we hypothesized that communication about sex may have been linked with risk for out YMSM because parents could concurrently send rejecting messages about a child’s sexual orientation while communicating about sex (e.g., “gay men get HIV when they have sex”), and parental rejection has been linked with risk behavior [16]. Researchers have asserted the quality of parent-adolescent communication about sex has distinct associations with adolescent sexual behavior in general adolescent samples [19, 20], but our prior study of YMSM assessed only the frequency of communication about sex. In a separate study, researchers reported differing associations between mother-son communication about sex and HIV testing behavior among YMSM of color based on the topic being discussed [21]. YMSM who reported frequent conversations with their mothers about same-sex sexual behaviors were more likely to be routinely tested, but YMSM were less likely to be tested if they reported frequently discussing general human sexuality and puberty with their mother [21].

In summary, previous research within general adolescent samples where sexual orientation is not assessed has indicated there is a small association between parent-adolescent communication about sex and increased safer sex behaviors, and little is known about how parent-adolescent communication about sex is associated with sexual behaviors of YMSM. Initial results from samples of YMSM indicate findings from heterosexual samples might not generalize to this population. Additionally, the vast majority of prior studies have examined the direct associations between parent-adolescent communication about sex and adolescent sexual risk behavior without including theoretically-grounded mediators of this association. Adolescent sexual behaviors are shaped by many forces, including opportunities to have sex, peer influences, and the interpersonal dynamics of specific sexual encounters [22, 23]. Rather than attempt to isolate simple direct effects between communication and sexual behaviors, an alternate approach involves examining how parent-adolescent communication is associated with theory-derived psychosocial variables that exist upstream of sexual behavior and serve as a foundation for adolescent decision making about condoms when they do have opportunities to engage in sex [11]. Research examining associations between theory-derived determinants of sexual risk behavior and parent-adolescent communication about sex has the potential to identify more specific targets for family-focused HIV-risk reduction interventions.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is one theoretical framework that has been applied widely and successfully in the prediction of sexual behavior [24–26]. Extensive research with MSM in particular, beginning early in the epidemic, has demonstrated that TPB constructs are useful in understanding sexual risk behavior in this population [27, 28], including among younger men [29]. This theory posits behavioral intentions predict actual behavior, and intentions are predicted by attitudes about the behavior as well as subjective norms related to the behavior [26]. Attitudes constitute the perceived positive or negative valence of beliefs about the behavior, and subjective norms are perceived social pressures to either perform or not perform a behavior [25]. In addition, perceived behavioral control, or perceived self-efficacy to successfully carry out the behavior, is associated with both behavioral intentions and behavior itself [25, 26].

Using TPB as a guide, we can then examine which determinants of behavior could be influenced by parent- adolescent communication about sex. One prior study using this approach showed that presumably heterosexual adolescents who reported higher quality communication about sex also reported more positive attitudes about condoms, more approving parental norms about condom use, and higher perceived behavioral control for condom use [30]. Adolescents who reported more positive attitudes and higher perceived behavioral control reported higher intentions to use condoms and, subsequently, higher condom use.

The Current Study

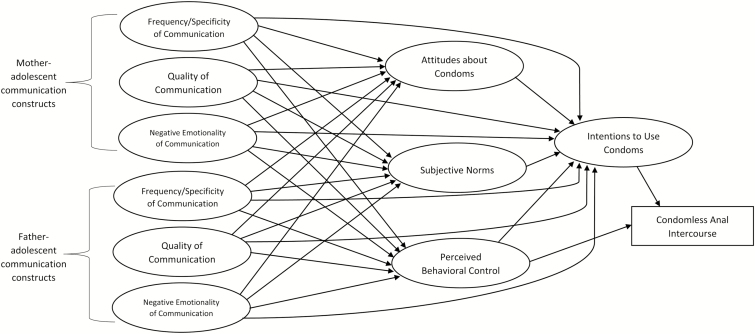

The primary aim of the current study was to examine how constructs of parent-adolescent communication about condoms are associated with determinants of condom use behavior and CAI among YMSM. Our hypothesized model is presented in Fig. 1. We further hypothesized that facets of parent-adolescent communication about sex would be most strongly related to foundational constructs from the TBP (e.g., attitudes about condoms, perceived behavioral control), and anticipated that “downstream” effects on behavioral intentions and actual behavior might be weaker, given the multiply-determined nature of adolescent sexual behavior.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized structural model depicting all included structural paths.

Method

Procedure

YMSM participated in an online cross-sectional survey from February to May 2015. Youth were recruited via advertisements on Facebook that were targeted to adolescent males in the USA, ages 14–18, whose profiles also included indicators that they would affiliate with keywords such as: “LGBT community,” “LGBT culture,” “LGBT social movements,” “Gay pride,” “Pride parade,” “Bisexuality,” “Coming out,” “Homosexuality,” “Gay-straight alliance,” “Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network,” and other LGBT-relevant topics. Ads were served a total of 76,106 times, and 6,822 clicks on the ad were recorded during recruitment. Clicking the ad opened the survey webpage, which was hosted on a secure server. A total of 3,050 participants began responding to survey questions, which took 25–45 min to fully complete. Participants completing the survey provided their email address if they wished to be entered into a lottery for one of ten $50 gift cards. The study was approved by the investigators’ Institutional Review Board.

Steps were taken to ensure the quality of the data. As suggested in previous online studies of YMSM [31], Internet Protocol (IP) addresses were used to identify potentially invalid cases, and data from cases with the same IP address were examined by hand to determine whether each case was valid (based on both demographic characteristics and survey timestamps). Four-hundred and two cases were identified which had the same IP address as another case. After examination, 176 cases were determined to be duplicate entries and removed, and 225 cases were determined to be unique entries and were retained. Finally, outlier analysis indicated two cases represented a pattern of inappropriate responding to study questions, and these cases were removed. This resulted in a total of 2,872 unique cases that provided some amount of data.

In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether random or careless responses degraded the quality of our data. Three items from the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory infrequency scale [32] were included as a means of identifying participants who were responding carelessly or randomly, or who might have been thought disordered. The pattern of results did not change in the structural model when YMSM with high scores on this scale were omitted from analysis, so all cases were included.

Participants

YMSM were eligible to participate in the study if they reported their gender assigned at birth was male, they had not undergone gender reassignment surgery, they were between the ages of 14 and 18, and they identified their current sexual orientation as gay, homosexual, or bisexual. Facebook advertising based on these criteria yielded 2,872 unique individuals who began the survey, and 947 participants provided enough data to be considered for analysis. No initial eligibility screening procedure was implemented for the online survey, and Facebook advertising accurately but imperfectly targets potential participants. Thus, 109 participants who did not meet eligibility criteria were removed following data collection, and 838 eligible participants were included in the present analyses. Participants’ mean age was 16.55 (SD = 1.25). Fifty-three percent identified their race/ethnicity as White, 15% as Black, 13% as Latino, 2% as Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% as Native American, and 16% as mixed race/ethnicity. Sixty-three percent of participants reported they lived with both parents full time, 17% reported single-parent households, 15% reported splitting time between their parents’ homes, and 5% reported they did not live with their parents. Seventy-two percent of participants identified their sexual orientation as gay or homosexual, and 28% identified as bisexual. Fifty-three percent of YMSM reported all parents who lived with them were aware of their sexual orientation, and 47% reported not all their parents were aware of their sexual orientation. Ninety-seven percent of participants identified their current gender identity as male, and 3% identified as genderqueer or transgender.

Eligible participants who provided sufficient data for analysis were more likely to identify their race/ethnicity as White and less likely to identify as Black compared to those who did not provide sufficient data. There were no other differences between eligible participants who provided sufficient data and those who did not.

Measures

Parent-adolescent communication about condoms among YMSM

Parent-adolescent communication about condoms was assessed using a scale which was constructed based on qualitative data from YMSM and their parents, and validated within the present sample [33]. Items were chosen to assess both the frequency and quality of parent-adolescent communication. The scale measured three discrete factors of parent-adolescent communication about condoms among YMSM with 17 items, including frequency and specificity of communication, quality of communication, and negative parent emotionality during communication (see Table 2 for specific items). The frequency and specificity scale assessed how often and in how much detail YMSM discussed condom use with their parents. The quality scale included items which assessed YMSM’s perceptions of parent knowledge, trustworthiness, and honesty during conversations about condoms. The negative emotionality scale measured how frustrated, upset, and worried parents were when discussing condoms. All items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale of 0 (never; not at all) to 4 (regularly; extremely). Participants reported whether they had one or two parental figures, and they were then presented with each communication question once and asked to respond separately for their first parent and second parent (if relevant) for each communication item. Each scale demonstrated strong internal consistency within both mother and father data (α = 0.94 and 0.94, respectively, for frequency and specificity; α = 0.87 and 0.86 for quality; α = 0.92 and 0.91 for negative emotionality).

Table 2.

Measurement model results for parent-adolescent communication and condom use determinant latent constructs

| Latent constructs and variables | Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-Adolescent Communication Constructs | Mother Measures | Father Measures | ||||

| Frequency/Specificity of Communication about Condoms | ||||||

| How often have you and your parent talked about condoms? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | 1.00 | 0.00 | - |

| How often has your parent explained how to put on a condom? | 0.60 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.64 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| How often have you and your parent talked about how to get condoms? | 0.95 | 0.04 | <.001 | 1.01 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| How often have you and your parent talked about how to discuss condom use with a sexual partner? | 0.98 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.92 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| In how much detail have you and your parent talked about condoms? | 1.10 | 0.04 | <.001 | 1.19 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| In how much detail have you and your parent talked about how to put on a condom? | 0.76 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.87 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| In how much detail have you and your parent talked about how to get condoms? | 1.04 | 0.05 | <.001 | 1.09 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| In how much detail have you and your parent talked about how to discuss condom use with a sexual partner? | 1.01 | 0.05 | <.001 | 1.04 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Quality of Communication about Condoms | ||||||

| How open is your parent to answering any question about condoms? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | 1.00 | 0.00 | - |

| How knowledgable is your parent about condoms? | 0.61 | 0.04 | <.001 | 0.63 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| How much do you trust what your parent has to say about condoms? | 0.92 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.95 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| How honest are your parents when they talk with you about condoms? | 1.08 | 0.05 | <.001 | 1.13 | 0.05 | <.001 |

| How much does your parent look out for what's best for you when the two of you talk about condoms? | 1.14 | 0.05 | <.001 | 1.17 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Negative Emotionality of Communication about Condoms | ||||||

| How upset is your parent when the two of you talk about condoms? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | 1.00 | 0.00 | - |

| How angry is your parent when the two of you talk about condoms? | 0.93 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.85 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| How frustrated is your parent when the two of you talk about condoms? | 1.04 | 0.06 | <.001 | 1.01 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| How worried is your parent when the two of you talk about condoms? | 1.39 | 0.07 | <.001 | 1.23 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Attitudes about Condoms | ||||||

| How much do you like condoms? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | |||

| How good are condoms? | 0.92 | 0.05 | <.001 | |||

| How valuable are condoms? | 0.98 | 0.08 | <.001 | |||

| How important are condoms? | 0.78 | 0.07 | <.001 | |||

| How pleasant are condoms? | 0.80 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| Subjective Norms for Condom Use | ||||||

| How much do people who are important to you think you should use condoms? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | |||

| How much do other guys your age think you should use condoms? | 0.71 | 0.07 | <.001 | |||

| How much is it expected of you that you use condoms? | 1.05 | 0.07 | <.001 | |||

| How much would people whose opinions you value approve of you using condoms? | 1.00 | 0.06 | <.001 | |||

| Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | ||||||

| How confident are you that you could use condoms if you wanted to? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | |||

| How much is using condoms completely up to you? | 0.75 | 0.10 | <.001 | |||

| How difficult is it to use condoms? | 0.40 | 0.06 | <.001 | |||

| Intentions to Use Condoms | ||||||

| How much do you plan to use condoms when you have sex? | 1.00 | 0.00 | - | |||

| How much of an effort will you make to use condoms? | 0.96 | 0.03 | <.001 | |||

| How much do you intend to use condoms when you have sex? | 1.07 | 0.02 | <.001 | |||

Estimate = Unstandardized regression weight; SE = standard error of Estimate; p = p-value.

Participants were instructed to respond for their most important parents/caregivers, and participants were given the option to select caregivers who were not their biological parent (including grandparents, stepparents, adoptive parents, aunts, and uncles). Caregivers were categorized as parents for the current study if they were related to the participant and were not in the same generation as the participant (siblings and cousins were not categorized as parents). Ninety-five percent of female caregivers selected were mothers (including biological, step-, and adoptive mothers), and 98% of selected male caregivers were fathers. Thus, we refer to caregivers as parents throughout this manuscript since the vast majority of YMSM were reporting on parents.

Determinants of condom use behavior

Attitudes, perceived norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions to use condoms were assessed with items recommended by Ajzen [34]. Five items measured attitudes about condoms (e.g., “How much do you like condoms?”), four items measured subjective norms (e.g.. “How much do people who are important to you think you should use condoms?”), perceived behavioral control was measured with three items (e.g., “How confident are you that you could use condoms if you wanted to?”), and intentions to use condoms were measured by three items (e.g., “How much do you plan to use condoms when you have sex?”). Items were assessed with five-point Likert scales. Attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = 0.82, α = 0.73, α = 0.91). Reliability of perceived behavioral control was lower in this sample (α = 0.56), but was deemed to be acceptable using an approximate threshold of 0.60 because the construct and items are theoretically indicated and the scale included only three items [35].

Additional measures

Condom use was assessed with a count variable of total instances of CAI in the past 6 months with any male partner. Insertive and receptive instances were summed into one CAI count for each participant. Race/ethnicity was assessed with one question asking participants to select all races/ethnicities with which they strongly identified. Sexual orientation was assessed with one question asking YMSM about self-identification of sexual orientation. Outness about sexual orientation to parents was assessed for each reported parental figure, and a trichotomous variable was calculated which has been used in prior studies of YMSM using scores of 0 (all parents do not know about sexual orientation), 1 (uncertain or mixed knowledge among parents), and 2 (all parents are aware of sexual orientation) [18]. Subjective social status was measured with the McArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status [36].

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling was used to examine associations between variables of interest using Mplus Version 8 [37]. Initially, a measurement model was calculated, modifications were made to the model based on fit and modification indices, and then a final measurement model was estimated. Measurement model included the three parent communication subscales separately for mothers and fathers (six constructs total), as well as all other relevant study constructs (condom attitudes, norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions). Following specification of the measurement model, a structural model was fit to examine hypothesized associations between latent constructs, measured covariates, and instances of reported CAI. Because CAI was measured as a count variable, models were estimated with a zero-inflated negative binomial estimator to account for zero-inflation resulting from participants who reported no sexual activity being coded as “0” on CAI. This analytic approach estimates separate equations predicting the counts for participants who are non-zeros and a logit equation predicting membership in the zero group. Negative binomial regression was preferred to Poisson regression because the distribution of CAI evidenced overdispersion [38].

The measurement model included latent constructs for both mother and father frequency and specificity of parent-adolescent communication about condoms, quality of communication, negative emotionality of communication. Additionally, models included latent constructs for attitudes about condoms, subjective norms for condom use, perceived behavioral control of condom use, and intentions to use condoms. Parent-adolescent communication constructs were allowed to correlate with each other, and, given prior evidence that attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control are correlated within samples of YMSM [39], these variables were allowed to correlate.

After obtaining adequate fit for the measurement model, our hypothesized structural model was estimated (see Fig. 1). Paths from each parent communication construct to attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions were included. Paths from attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control to intentions were also included. Paths from intentions and perceived behavioral control to instances of CAI were included, but paths from communication constructs, attitudes, and norms to CAI were not included because they were not theoretically indicated. Age, outness, sexual orientation, subjective social status, and race/ethnicity were included in each model, and paths from demographic covariates to communication constructs were included.

Because several variables evidenced inherent skewness, maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors that are robust to non-normality (MLR) were used to estimate models [40]. This procedure estimates a chi-square test statistic that is equivalent to a Yuan-Bentler T2 chi-square test statistic [41] and uses full-information maximum likelihood procedures to address missing data [42]. Global model fit of the measurement model was assessed with multiple indicators, including the chi-square test of model fit, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Models were deemed to demonstrate satisfactory fit when two of three fit indices met the following criteria: CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 [43]. Numerical integration was required to estimate structural model, and absolute and comparative fit indices cannot be estimated when using this procedure. Thus, information theory goodness of fit measures were used to compare model fit of the structural equation model to similar structural models. Fit measures included the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the sample-size adjusted BIC (SABIC), with lower values on these measures indicating superior fit [44]. Finally, the Monte Carlo method was used to estimate confidence intervals for indirect effects [45] using 20,000 iterations, and 95% confidence intervals excluding zero were interpreted as significant.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Intercorrelations among study variables are included in Table 1. Age, sexual orientation, outness, and subjective social status were associated with study variables and were included as covariates in structural models. A dichotomized sexual orientation variable was included (gay/homosexual vs. bisexual), and two dummy coded variables comparing YMSM who reported mixed/uncertain outness and full outness to YMSM who denied all parent knowledge of orientation were included. ANOVA analyses indicated race/ethnicity (coded as White, Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, and other) was associated with study variables, and three dummy codes comparing groups to White participants were included in the structural model. Additionally, mean group differences were examined for each communication construct across mother and father data for participants who reported on both parents. Participants reported their mothers communicated with higher levels of frequency and specificity (t[569] = 5.82, p < .001), quality (t[567] = 6.18, p < .001), and negative emotionality (t[562] = 6.39, p < .001) when compared to their fathers.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations among study variables

| Variable | Age | Sexual orientation | Outness | Subjective social status | Mother frequency and specificity | Mother quality | Mother negative emotionality | Father frequency and specificity | Father quality | Father negative emotionality | Attitudes | Subjective norms | Behavioral control | Intentions | Condomless anal intercourse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -- | −0.057 | 0.043 | −0.020 | −0.020 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.043 | 0.011 | −0.004 | 0.029 | 0.114** | −0.013 | 0.093** |

| Sexual orientation | -- | −0.306** | 0.005 | 0.028 | 0.008 | −0.004 | 0.118** | 0.051 | −0.011 | −0.014 | 0.009 | 0.001 | −0.060 | −0.045 | |

| Outness | -- | 0.003 | 0.171** | 0.228** | 0.136** | 0.064 | 0.219** | 0.095* | −0.064 | −0.039 | −0.021 | −0.028 | 0.102** | ||

| Subjective social status | -- | 0.026 | 0.121** | 0.008 | 0.053 | 0.182** | 0.024 | 0.111** | 0.168** | 0.056 | 0.117** | −0.044 | |||

| Mother frequency and specificity | -- | 0.544** | 0.433** | 0.727** | 0.373** | 0.356** | 0.183** | 0.170** | 0.171** | 0.154** | −0.005 | ||||

| Mother quality | -- | 0.391** | 0.366** | 0.805** | 0.267** | 0.160** | 0.286** | 0.200** | 0.165** | 0.006 | |||||

| Mother negative emotionality | -- | 0.319** | 0.235** | 0.513** | 0.038 | 0.052 | 0.065 | 0.097** | 0.067 | ||||||

| Father frequency and specificity | -- | 0.470** | 0.490** | 0.145** | 0.127** | 0.098* | 0.094* | −0.035 | |||||||

| Father quality | -- | 0.322** | 0.078 | 0.240** | 0.154** | 0.069 | −0.020 | ||||||||

| Father negative emotionality | -- | 0.039 | 0.068 | 0.062 | 0.028 | 0.124** | |||||||||

| Attitudes | -- | 0.496** | 0.394** | 0.641** | −0.196** | ||||||||||

| Subjective norms | -- | 0.322** | 0.519** | −0.149** | |||||||||||

| Behavioral control | -- | 0.385** | 0.008 | ||||||||||||

| Intentions | -- | −0.264** | |||||||||||||

| Condomless anal intercourse | -- |

Results reflect Pearson correlation coefficients; *p < .05; **p < .01.

Fifty-seven percent of participants (n = 481) reported they were sexually active in the past 6 months (defined as “any activity where you touch your partner and become sexually aroused”). Of these participants, 349 reported any anal intercourse, and 259 reported any CAI in the past 6 months. YMSM who denied any sexual activity in the past 6 months were coded as “0” on the CAI variable. CAI had a range of 0–252, a mean of 6.88 (SD = 27.06), a median of 0, and an interquartile range of 1. Participants were asked whether they had ever been HIV tested and what their results were: no participants endorsed a positive HIV test result.

Measurement Model

The initial model demonstrated inadequate fit (χ2 [1,082] = 5,638.56, p < .001; CFI = 0.78, RMSEA = 0.071, SRMR = 0.06). Modification indices suggested paired items on the mother and father communication scales and similarly worded indicators of the frequency and specificity construct were contributing to model misspecification because of shared variance in measurement error among these items [46], so paired items on scales and similarly worded items on frequency and specificity scales were allowed to have correlated errors (results presented in Table 2). Data then fit the modified measurement model sufficiently (χ2 [1,057] = 2,719.30, p < .001; CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.05). No further modifications were made to the measurement model.

Structural Model

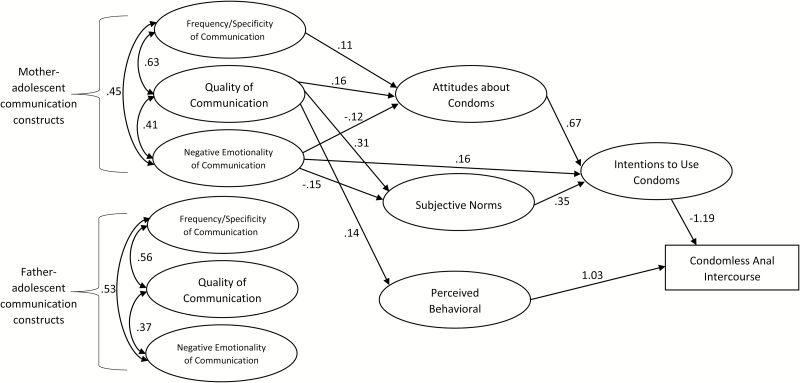

Within the structural model, frequency and specificity of mother-adolescent communication were positively associated with attitudes about condoms. Quality of mother communication was positively associated with attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral control. Mother negative emotionality was negatively associated with both attitudes and subjective norms, and was directly negatively associated with intentions to use condoms. Intentions to use condoms were also positively associated with attitudes and subjective norms, and intentions then significantly predicted the count portion of the CAI outcome. After controlling for intentions in the same equation, behavioral control was positively associated with the count portion of CAI. No associations between father-adolescent communication constructs and determinants of condom use behavior were detected. Results from the structural model are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2. The model fit of the zero-inflated negative binomial model was deemed to be superior as compared to a negative binomial model without zero inflation based on lower AIC (80,736.11 v. 80,767.12) and SABIC (81,219.08 v. 81,233.01) values. While BIC of the zero-inflated model was higher than the non-zero-inflated model (82,206.71 v. 82,185.71), this measure includes a penalty for model complexity [44].

Table 3.

SEM results illustrating associations between parent-adolescent communication about condoms, determinants of condom use behavior, and condomless anal intercourse

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directional Structural Effects | ||||

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | 0.11 | 0.05 | 2.03 | .043 |

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.47 | .637 |

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.70 | .089 |

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | −0.05 | 0.05 | −1.08 | .280 |

| Mother Quality of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | 0.16 | 0.05 | 2.97 | .003 |

| Mother Quality of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.31 | 0.06 | 5.53 | <.001 |

| Mother Quality of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.14 | 0.06 | 2.47 | .013 |

| Mother Quality of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | −0.42 | 0.05 | −0.83 | .405 |

| Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | −0.12 | 0.05 | −2.53 | .011 |

| Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | −0.15 | 0.05 | −2.98 | .003 |

| Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.76 | .449 |

| Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | 0.16 | 0.05 | 2.90 | .004 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.37 | .170 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.05 | .961 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | −0.07 | 0.07 | −1.02 | .309 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.50 | .616 |

| Father Quality of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | −0.09 | 0.06 | −1.43 | .151 |

| Father Quality of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.31 | .759 |

| Father Quality of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.31 | .757 |

| Father Quality of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.78 | .438 |

| Father Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Attitudes about Condoms | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.10 | .918 |

| Father Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.34 | .734 |

| Father Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.95 | .343 |

| Father Negative Emotionality of Communication --> Intentions to Use Condoms | −0.10 | 0.07 | −1.48 | .140 |

| Attitudes about Condoms --> Intentions to Use Condoms | 0.67 | 0.09 | 7.84 | <.001 |

| Subjective Norms for Condom Use --> Intentions to Use Condoms | 0.35 | 0.09 | 3.92 | <.001 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use --> Intentions to Use Condoms | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.55 | .122 |

| Intentions to Use Condoms --> Condomless Anal Intercourse (Count) | −1.19 | 0.23 | −5.28 | <.001 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use --> Condomless Anal Intercourse (Count) | 1.03 | 0.38 | 2.75 | .006 |

| Intentions to Use Condoms --> Condomless Anal Intercourse (Logit) | 1.05 | 0.36 | 2.89 | .004 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control for Condom Use --> Condomless Anal Intercourse (Logit) | 0.02 | 0.53 | 0.04 | .965 |

| Latent Variable Correlations | ||||

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication < > Mother Quality of Communication | 0.58 | 0.05 | 11.66 | <.001 |

| Mother Frequency/Specificity of Communication < > Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication | 0.28 | 0.03 | 10.15 | <.001 |

| Mother Quality of Communication < > Mother Negative Emotionality of Communication | 0.29 | 0.03 | 8.76 | <.001 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication < > Father Quality of Communication | 0.38 | 0.05 | 8.07 | <.001 |

| Father Frequency/Specificity of Communication < > Father Negative Emotionality of Communication | 0.26 | 0.03 | 10.27 | <.001 |

| Father Quality of Communication < > Father Negative Emotionality of Communication | 0.24 | 0.04 | 6.57 | <.001 |

| Attitudes about Condoms < > Subjective Norms for Condom Use | 0.33 | 0.03 | 10.76 | <.001 |

| Attitudes about Condoms < > Percevied Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.28 | 0.03 | 8.34 | <.001 |

| Subjective Norms for Condom Use < > Percevied Behavioral Control for Condom Use | 0.24 | 0.04 | 6.50 | <.001 |

All structural effect estimated while covarying age, subjective social status, sexual orientation, outness, and race/ethnicity. Estimate = Unstandardized regression weight; SE = standard error of Estimate; Z = Z-test of Estimate = 0; p = p-value for Z-test.

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model examining associations between parent-adolescent communication constructs, determinants of condom use behavior, and condomless anal intercourse (CAI). Paths significant at P < .05 represented by solid line. Unstandardized estimate included for each path. Correlations between attitudes, norms, and behavioral control, as well as all estimated non-significant paths, were omitted to enhance clarity. Associations with CAI are reported for the count portion of this outcome. Value for all estimated paths (significant and non-significant) can be found in Table 3.

Indirect effects in both structural models were examined to determine whether parent-adolescent communication constructs exerted influence on intentions to use condoms and CAI. Mother-adolescent communication about condoms evidenced several indirect associations with intentions and the count portion of CAI (see Table 4). The frequency and specificity of communication was positively associated with intentions to use condoms via attitudes, quality of communication was positively associated with intentions via attitudes and subjective norms, and negative emotionality was negatively associated with intentions via attitudes and subjective norms. Frequency and specificity was also negatively associated with CAI via attitudes via intentions, quality of communication was negatively associated with CAI via attitudes and subjective norms via intentions, and negative emotionality was positively associated with CAI via attitudes and subjective norms via intentions. Additionally, negative emotionality was also negatively associated with CAI via intentions in the same model, indicating that higher negative emotionality was associated with both higher and lower risk of CAI via different mechanisms. No significant mediated effects were found for father-adolescent communication.

Table 4.

Indirect effects between parent-adolescent communication about condoms and intentions and CAI

| Indirect Effect | Unstandardized estimates | 95% confidence interval | Unstandardized estimates | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency/specificity of communication | Mother communication effects | Father communication effects | ||

| Effect on CAI mediated directly through intentions | 0.06 | −0.053–0.183 | −0.04 | −0.211–0.116 |

| Effect on CAI mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes --> Intentions | −0.09* | −0.188–−0.003 | −0.09 | −0.228–0.037 |

| Subjective Norms --> Intentions | −0.01 | −0.057–0.033 | 0.00 | −0.064–0.064 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control --> Intentions | −0.01 | −0.048–0.006 | 0.01 | −0.012–0.032 |

| Effect on Intentions mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes | 0.07* | 0.003–0.150 | 0.07 | −0.031–0.185 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.01 | −0.027–0.046 | 0.00 | −0.053–0.052 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.01 | −0.006–0.038 | −0.01 | −0.040–0.010 |

| Quality of Communication | ||||

| Effect on CAI mediated directly through intentions | 0.05 | −0.064–0.184 | 0.05 | −0.087–0.193 |

| Effect on CAI mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes --> Intentions | −0.13* | −0.252–−0.037 | 0.07 | −0.024–0.190 |

| Subjective Norms --> Intentions | −0.13* | −0.239–−0.052 | −0.01 | −0.060–0.045 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control --> Intentions | −0.02 | −0.072–0.005 | 0.00 | −0.031–0.024 |

| Effect on Intentions mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes | 0.11* | 0.035–0.192 | −0.06 | −0.146–0.023 |

| Subjective Norms | 0.11* | 0.052–0.177 | 0.01 | −0.036–0.050 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.02 | −0.005–0.055 | 0.00 | −0.018–0.027 |

| Negative Emotionality of Communication | ||||

| Effect on CAI mediated directly through intentions | −0.19* | −0.336–−0.054 | 0.12 | −0.035–0.308 |

| Effect on CAI mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes --> Intentions | 0.10* | 0.020–0.189 | 0.01 | −0.105–0.111 |

| Subjective Norms --> Intentions | 0.06* | 0.031–0.134 | −0.01 | −0.063–0.049 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control --> Intentions | 0.01 | −0.012–0.032 | −0.01 | −0.052–0.011 |

| Effect on Intentions mediated through: | ||||

| Attitudes | −0.08* | −0.158–−0.018 | −0.01 | −0.094–0.086 |

| Subjective Norms | −0.05* | −0.104–−0.015 | 0.01 | −0.039–0.053 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | −0.01 | −0.025–0.010 | 0.01 | −0.010–0.038 |

* Indicate significance at .05 level; 95% confidence intervals estimated using the Monte Carlo method.

CAI = condomless anal intercourse.

Finally, because CAI was measured as behaviors occurring over the previous 6 months, it is plausible that the direction of causality in our models was reversed and that CAI actually influenced subsequent communication and determinants of condom use behavior. To examine this alternative model, a structural model was estimated in which communication constructs and determinants of behavior were predicted by CAI. Paths between CAI and attitudes and subjective norms were significant in this model, but CAI was not significantly associated with perceived behavioral control. All paths between CAI and communication constructs were nonsignificant in this model, indicating that this model did not present a conceptually superior alternative to the above tested model. Additionally, higher AIC (80,813.33 v. 80,736.11), BIC (82,231.92 v. 82,206.71), and SABIC (81,279.22 v. 81,219.08) values indicated this alternate model evidenced poorer fit to observed data than the above-reported structural model.

Discussion

Parent-adolescent communication about condoms is associated with determinants of condom use behavior among YMSM, and indirectly, with condom use itself. Mother-adolescent communication that is perceived by youth as frequent, specific, high quality, and low in negative emotionality is associated with more positive attitudes about condoms, higher subjective norms, and higher perceived behavioral control among YMSM. In turn, indirect effects link mother-adolescent communication about sex with higher intentions to use condoms and fewer instances of CAI. Within the same model, father-adolescent communication about condoms was not associated with determinants of condom use behavior.

Interestingly, indirect effects within the mother model indicate mother-adolescent communication about condoms might both negatively and positively influence intentions to use condoms and subsequent CAI. Higher frequency and specificity and quality of communication were associated with more favorable attitudes and norms, and these protective effects were then indirectly associated with increased intentions to use condoms and lower CAI. Additionally, greater negative emotionality was associated with less favorable condom-related attitudes and norms, but, when controlling for attitudes and norms, higher negative emotionality was directly associated with higher intentions.

Although partly unexpected, these results could help to explain prior findings that more frequent parent-adolescent communication about sex was linked with CAI within another sample of YMSM [18]. This previous study measured only frequency of communication about sex, and the current findings indicate it could be possible for mothers to both erode and enhance YMSM intentions to use condoms based on the way they communicate. Higher levels of mother negative emotionality during communication were associated with lower intentions via attitudes and norms, and, at the same time, more negative emotionality was associated with higher intentions to use condoms, presumably via mechanisms unmeasured in the current study. Mother-adolescent communication that is more emotional could lead YMSM to have less favorable attitudes about condoms and perceive less strong norms for their use. However, mothers expressing negative emotions during communication also might motivate YMSM to use condoms, perhaps because emotionality suggests that a mother’s guidance is urgent, or because it indirectly tells YMSM that their sexual health is important to their mother.

Furthermore, our prior study of YMSM found that outness to parents moderated the association between CAI and a brief, general measure of parent-adolescent communication about sex [18], such that more communication with YMSM who were out was associated with greater risk. We speculated that this might be because parents communicate in qualitatively different ways with YMSM once they come out, not all of which are helpful. Findings from the present study are consistent with this idea. Within the structural model, outness had direct associations with each parent communication construct (with the exception of father emotionality), such that YMSM who were fully out to their parents reported more frequent and specific communication about condoms and higher quality communication compared to YMSM who were not out to their parents. In these ways, men who are out to parents receive more communication that is generally protective. However, YMSM who were fully out also reported that their moms communicated with greater negative emotionality, compared to men who were less out. As we have discussed, the effect of negative emotionality on condom-use determinates is mixed. This suggests that some kinds of parent communication that occur after a YMSM comes out also have the potential to increase risk. Future research and intervention work must be mindful of the varied facets of communication, not all of which are helpful, and should consider how the coming out process causes that communication to evolve.

Results from the current study not only inform us of how parent-adolescent communication about condoms functions within families of YMSM, but they also shed light on mechanisms underlying associations found among heterosexual adolescents in the broader literature. Researchers have found that mothers exert a small protective influence on adolescent sexual behavior by communicating with their adolescents about sex, but that fathers do not exert any influence [15]. The current study shows that associations between communication about sex and safer sex behaviors are mediated by determinants of condom use behavior, and mothers exert a stronger, more wide-reaching influence on these determinants. Researchers should attempt to generalize these findings to heterosexual adolescents by examining intrapersonal determinants of condom use as potential mediators underlying the association between parent-adolescent communication about sex and safer sex behavior.

Different associations between communication and determinants of behavior across mothers and fathers could be attributed to several differences in the way mothers and fathers communicate with YMSM about condoms. YMSM reported their mothers communicated about condoms with more frequency and specificity, quality, and negative emotionality than their fathers, and thus, fathers’ generally limited influence could result from the fact that they are simply communicating less. This explanation could hold true for heterosexual adolescents as well, as fathers have been found to communicate about sex less frequently and with lower quality than mothers in previous research [10, 47, 48]. Our findings of limited father influence might also result from the fact that we considered fathers in models jointly with mothers. Father-adolescent communication about condoms evidenced several bivariate associations with determinants of condom use behavior, as well as a bivariate association revealing that greater negative emotionality in father communication was associated with greater CAI. These associations were not sustained within the multivariate structural model. This might result, in part, from the way in which regression analyses and structural equation modeling assign shared variance between predictors and an outcome. Because mother communication had stronger bivariate associations with all outcomes, any variance that mothers and fathers shared with an outcome is arbitrarily assigned to mothers. Future investigations should continue to examine the distinct contributions of mothers and fathers within studies of parent-adolescent communication about sex among YMSM.

The present study’s findings regarding perceived behavioral control were unexpected on several fronts. First, the measure of perceived behavioral control had lower reliability than in numerous previous studies utilizing the same measure, as well as lower reliability than other constructs measured in the present study. However, the items were deemed to sufficiently measure the intended construct because they are theoretically indicated within studies of the TPB, and the limitation of reliability is mitigated by our use of structural equation modeling to estimate latent constructs. At the bivariate level, behavioral control was unassociated with CAI and evidenced associations in the expected direction with other constructs of interest, including a positive association with intentions. However, within the multivariate equation predicting CAI, behavioral control was positively associated with CAI, after controlling for intentions. Given these issues, we hesitate to draw firm conclusions about our findings related to behavioral control. Future studies of adolescent YMSM should continue to investigate both how best to measure perceived behavioral control within this population, and how to test its association with HIV-related sexual risk behaviors in the most theoretically coherent way.

The current investigation is limited by its cross-sectional design. YMSM reported their current attitudes, perceived norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions as well as prior experiences of communication with their parents about condoms, so the structural model examining the sequence of constructs up through intentions is consistent with a theoretical model in which these variables are temporally ordered and causally influence one another. However, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, we cannot rule out other directions of effect. In particular, caution must be used when interpreting associations with CAI within the structural models, as this behavior was measured within the previous six months and could have contributed to the formation of attitudes and intentions or spurred conversations about condoms between parents and YMSM. However, our examination of an alternative model where CAI preceded communication constructs and determinants of behavior demonstrated that CAI did not significantly predict communication, indicating that a model where communication predicts determinants of condom use and subsequent CAI is best supported within the current cross-sectional dataset. Future work should employ prospective designs to disentangle bidirectional effects between sexual behavior, determinants of sexual behavior, and communication about sex. The study is also limited by the use of only YMSM’s reports of their communication with their parents, and triangulation of assessments from multiple reporters within the family would allow researchers to more thoroughly examine the dynamic nature of communication between YMSM and their parents. Finally, this study did not examine other family factors which evidence associations with adolescent sexual behavior, including parental monitoring, and future work should strive to investigate integrated models of parental influence which account for multiple family factors concurrently.

The current study contributes to the parent-adolescent communication about sex literature by using a theory-grounded framework, and findings indicate that mothers can communicate about condoms with YMSM in a way that could contribute to lower HIV-related sexual risk. Researchers have advocated for family-focused interventions for YMSM [49], and the current findings show enhanced mother-adolescent communication is a potential avenue for future intervention work. While father communication was unassociated with condom use intentions and CAI in the current study, no negative paternal associations were identified, and future interventions can only benefit from including all parents. When YMSM first come out and become sexually active, many do not have access to lesbian, gay, and bisexual community resources which provide information about sexual health, and parents could be included in interventions to assist in providing sexual health education at home before YMSM have access to other resources. Prevention efforts designed to help parents discuss sex with YMSM in a way that is specific to their sexual health needs could prove fruitful, and interventions would need to help parents build knowledge of and comfort with condoms, HIV, and same-sex sexual behaviors. Helping parents to communicate about condoms in a way that is well-informed, comfortable, specific, and calm, yet firm, has the potential to increase YMSM intentions to use condoms and reduce their HIV-related sexual risk behaviors.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Cynthia Berg, PhD, Lisa Diamond, PhD, Patricia Kerig, PhD, and Kelly Lundberg, PhD for their valued consultation throughout the current study and Carolyn Chen, BS for her assistance with data processing. This study was supported by NIMH grants F31MH098739 and T32MH018951.

Compliance with Ethical Standards Statements

Conflict of Interest B. C. Thoma and D. M. Huebner declare that they have no conflict of interest with the project. All research was conducted under the guidance and oversight of the University of Utah and University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Boards.

References

- 1. CDC. HIV Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. ; HIV Incidence Surveillance Group Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. Plos One. 2011;6(8):e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2013. February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. Young Men’s Survey Study Group. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balaji AB, Bowles KE, Le BC, Paz-Bailey G, Oster AM. High HIV incidence and prevalence and associated factors among young MSM, 2008. AIDS. 2013;27(2):269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CDC. HIV Infection Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors among Men Who Have Sex With Men—National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. Cities, 2014. January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2–3):218–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, et al. ; HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(2):228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G; National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US Cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiIorio C, Pluhar E, Belcher L. Parent-child communication about sexuality: a review of the literature from 1980–2002. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children. 2003;5(3/4):7–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: a conceptual framework. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2002;2002(97):9–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, et al. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(Suppl 3):S23–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hadley W, Brown LK, Lescano CM, et al. ; Project STYLE Study Group Parent-adolescent sexual communication: associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson HW, Donenberg G. Quality of parent communication about sex and its relationship to risky sexual behavior among youth in psychiatric care: a pilot study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, Nesi J, Garrett K. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heatherington L, Lavner JA. Coming to terms with coming out: review and recommendations for family systems-focused research. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(3):329–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thoma BC, Huebner DM. Parental monitoring, parent-adolescent communication about sex, and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(8):1604–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Jaccard J, Goldberg V, Casillas E, Bouris A. The content and process of mother—adolescent communication about sex in Latino families. Social Work Research. 2006;30(3):169–181. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Miller KS, Forehand R. Adolescent sexual risk-taking behavior in single-parent ethnic minority families. J Fam Psychol. 1999;13(1):93. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bouris A, Hill BJ, Fisher K, Erickson G, Schneider JA. Mother-Son Communication about sex and routine human immunodeficiency virus testing among younger men of color who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(5):515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lohman BJ, Billings A. Protective and risk factors associated with adolescent boy’s early sexual debut and risky sexual behaviors. J Youth Adolescence. 2008;37(6):723–735. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Widman L, Noar SM, Choukas-Bradley S, Francis DB. Adolescent sexual health communication and condom use: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014;33(10):1113–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Albarracín D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):142–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, eds. Action Control. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 1985:11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cochran SD, Mays VM, Clarletta J, Caruso C, Mallon D. Efficacy of the theory of reasoned action in predicting AIDS-related sexual risk reduction among Gay Men. J Applied Soc Psychol. 1992;22(19):1481–1501. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rye BJ, Fisher WA, Fisher JD. The theory of planned behavior and safer sex behaviors of Gay men. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(4):307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Franssens D, Hospers HJ, Kok G. Social-cognitive determinants of condom use in a cohort of young gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care. 2009;21(11):1471–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malcolm S, Huang S, Cordova D, et al. Predicting condom use attitudes, norms, and control beliefs in hispanic problem behavior youth: the effects of family functioning and parent–adolescent communication about sex on condom use. Health Education & Behavior. 2013;40(4):384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bauermeister J, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Diéguez A, Strecher VJ. Data quality in web-based HIV/AIDS research: handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods. 2012;24(3):272–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arbisi PA, Ben-Porath YS. An MMPI-2 infrequent response scale for use with psychopathological populations: the infrequency-psychopathology scale, F (p). Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):424. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thoma BC. Parent-Adolescent Communiaction about Sex and Condom Use among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men: An Examination of the Theory of Planned Behavior [Dissertation]: Department of Psychology, University of Utah; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ajzen I. Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript Retrieved 3/12/2016 Amherst, MA: Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Massachusetts; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loewenthal KM. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales. Hove, East Sussex, England: Psychology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Goodman E, Adler NE, Kawachi I, Frazier AL, Huang B, Colditz GA. Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muthén LK, Muthén BO.. Mplus User’s Guide (Sixth Edition). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull. 1995;118(3):392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kalichman S, Stein JA, Malow R, et al. Predicting protected sexual behaviour using the Information-Motivation-Behaviour skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(3):327–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Muthén BO, Muthén LK.. Mplus (Version 6) Los Angeles. CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yuan K-H, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology. 2000;30(1):165–200. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Model. 2001;8(3):430–457. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burnham KP, Anderson DR.. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-theoretic Approach. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6(2):77–98. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hoyle RH. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dutra R, Miller KS, Forehand R. The process and content of sexual communication with adolescents in two-parent families: associations with sexual risk-taking behavior. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3(1):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sneed CD. Parent-adolescent communication about sex: the impact of content and comfort on adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2008;9(1):70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Donenberg G. Parents know and parents matter; is it time to develop family-based HIV prevention programs for young men who have sex with men?J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(2):201–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]