Summary

Nowadays, the prevalence of both fast food consumption and overweight/obesity has been increased. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of fast food consumption and to assess its association with abdominal and general obesity. In an analytical cross-sectional study, 300 students were selected randomly from two largest universities in Qom, center of Iran, studying in medical and basic sciences fields in 2015. Data collection was conducted by a modified version of NELSON’s fast food questionnaire and anthropometric measures including Waist-Hip Ratio (WHR) and Body Mass Index (BMI). Chi-square, independent t-test, and multivariate logistic regression were used for statistical analysis. According to our results, 72.4% (67.4% in females vs 80.7% in males) had at least one type of fast food consumption in the recent month including sandwich 44.4%, pizza 39.7%, and fried chicken 13.8%, The obesity prevalence based on BMI and WHR was 21.3% (95% CI: 19.4, 23.2%) and 33.2% (95% CI: 0.7, 35.7), respectively. Fast food consumption was related to abdominal obesity as WHR (OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.11, 2.26), but was not related to general obesity as BMI (OR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.63, 1.52). The prevalence of fast food consumption and obesity/overweight in Iranian student is high. Fast food consumption was associated with abdominal obesity based WHR, but did not related to general obesity based on BMI.

Keywords: Abdominal obesity, Fast foods, Iran, Overweight, Students

Highlights

In adolescent students, 72.4% and 34% have used at least one type of fast foods in recent month and in recent week.

The obesity prevalence based on BMI and WHR was 21.3 % (18.2% in females vs 26.3% in males) and 33.2% (40.1% in females vs 21.9% in males), respectively.

Fast food consumption was associated with WHR, while was not related to BMI.

Sandwich consumption was associated with obesity/overweight based on BMI to 35%, fried chicken to 40%, and pizza more than 80%.

Introduction

The percentage of caloric intake from fast foods has increased fivefold over the past three decades among adolescents [1, 2]. In addition, obesity prevalence increased dramatically worldwide as one of the most serious public health problem especially in childhood and adolescents in current century [3]. Fast food consumption has increasing’ trend due to convenience, costs, menu choices, flavor and taste [4]. About 30% of children to more than 50% in college students use fast food daily[2, 5]. Moreover, more than 33% of adults and 17% of children and teenagers are obese in united states [6]. Increased food consumption and substantial changes in the food habits are the most important factors of obesity epidemic [7] besides the poor diet among young people at recent years [8].

Wide ranges of causes are associated with obesity and overweight that varied from genetic to environmental factors [3, 7]. However, our surround environment is one of the key factors that effective in the rapid development of the obesity epidemic in the world [7]. Fast food consumption is strongly associated with weight gain and obesity. Fast food consumption could increase the risk of obesity and obesity-related diseases as a major public health issue [9, 10]. Obesity and overweight are the most important factors of non-communicable diseases related to years of life lost in cardiovascular diseases [11, 12].

Fast food is defined by a convenience food purchased in self-service or carry out eating venues without wait service [9]. Todays, the number of women in the workforce is increased due to changes in the family structure and urbanization in all countries over the past years. Moreover, the working of people for longer hours expands and the food and mealtimes have changed seriously. A rapid growth is observed in fast food industries and restaurants [13]. Consequently, some worse consequences such as overweight and obesity have increasing trend [9]. Previous research has identified a strong positive association between the availability of fast food and its consumption as well as fast food consumption and obesity outcomes [5, 8, 10, 14, 15]. However, some studies assessed the fast food consumption on the general obesity based on Body Mass Index (BMI) [5, 8, 10, 16]. Nevertheless, the association between fast food consumption and obesity type (abdominal/general) is unclear [3, 10]. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of fast food consumption and obesity/overweight in two different governmental and nongovernmental universities, and to assess the association of fast food consumption with abdominal/general obesity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 300 students of two large Universities in Qom, center of Iran, that randomly selected and studying in medical and basic sciences fields at spring 2015. Sample size was calculated based on the fast food prevalence in recent studies with considering the power equal to 90% and first type error equal 5% as well as based on the minimal significant difference expected regarding fast food consumption between the two university and students who used and not used fast food. The study subjects were selected based on the multistage sampling method. In the first phase, according to the stratified random sampling method, 150 students selected from the Qom Medical University, and 150 students selected from a nongovernmental University (Qom branch of Islamic Azad University). Then in each stratum, simple random sampling was used for selecting some classes and recruitment of students. In the third phase, in each selected class, all the eligible students were called to participate in the study. After describing the objectives and the method of data gathering, the informed consent is taken from all the volunteer subjects. Moreover, the ethic committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences approve the study protocol.

Data collection was conducted by a modified version of standard NELSON’ fast food questionnaire [17]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire is assessed by them and reported as a reliable measure with fair validity. Moreover, the content validity of modified version of questionnaire changed based on cultural and nutritional differences in Iranian people, was assessed by experts in epidemiology, nutrition and health education majors. Moreover, the reliability of questionnaire was assessed by Cronbakh Alpha and estimated as 0.861.

The main outcomes in our questionnaire were fast food consumption, type of fast food and the frequency of consumption. The variables that evaluated in fast food consumption were selected based on more frequent items that used in Iran based on cultural and religious condition such as different types of sandwich, fried chicken, fried potato, hotdog and pizza.

Obesity indexes data of such as waist and circumference for calculating Waist-Hip Ratio (WHR), height and weight for computing BMI were collected. Waist, hip circumference, and height of subjects were measured by anthropometric tape measure. Moreover, the weight of students was measured by a valid scale (SECA 830). BMI and WHR were calculated by standard formulae [18, 19].

The WHR index was used for measuring the abdominal obesity and BMI for general obesity. Frequency, mean, and standard deviation were used for description of data. Chi-square test was used to assess the relationship between fast food consumption and quantitative demographic variables with obesity in studied subjects. Independent t-test were used for comparing the mean of age, BMI and WHR and their components in studied subjects between used and un-used fast food consumption. Finally, multivariate logistic regression was used to control the potential confounders including job, educational level, field of study and type of university. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (Chicago, IL, USA) and the type one error considered in 0.05 level.

Results

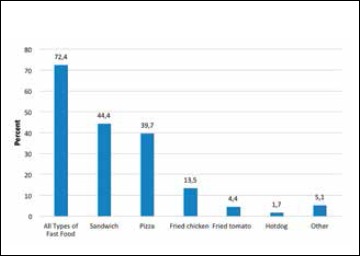

Overall, 72.4% (67.4% in females vs 80.7% in males) have fast food consumption. These students used at least one type of the fast foods in the recent month. However, the most common type of fast food consumption was sandwich 44.4%, pizza 39.7%, fried chicken 13.8%, respectively. Figure 1 showed the distribution of different type of fast foods in recent month after survey.

Fig. 1.

The prevalence of different the types of fast food consumption in studied students.

Table I shows the comparison of fast food consumption in students by chi square test between who were consumed fast food in recent month and who not consumed. This table showed that there was significant difference between subjects who used and did not use fast food in recent month regarding to the gender, marital status, education level, university, and major of study. The married and male students as well as who studied in basic sciences and nongovernmental university were used more fast food. Nevertheless, there was no significant relationship between job and residency place at night with fast food consumption.

Table II shows that there was a significant difference between studied subjects who used and not used fast food in past month regarding to waist and WHR (p < 0.05). Nevertheless, the difference in age, weight, height, hip, and BMI was not significant between two groups.

Tab. II.

Comparing the mean of age, BMI and WHR and their components in studied subjects between used and un-used fast food consumption.

| Used fast food | Not-used fast food | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value |

| Age (yr) | 21.37 | 2.20 | 21.52 | 2.40 | 0.619 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.20 | 11.30 | 61.90 | 11.2 | 0.130 |

| Height (cm) | 168.00 | 9.10 | 164.00 | 8.90 | 0.077 |

| Waist (cm) | 81.27 | 9.21 | 78.93 | 9.72 | 0.048 |

| Hip (cm) | 98.40 | 7.56 | 98.90 | 6.20 | 0.523 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.827 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.004 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.64 | 3.10 | 22.79 | 3.69 | 0.726 |

The overweight/obesity prevalence based on BMI classification (higher 25 kg/m2) was 21.3% (95% CI: 19.4, 23.2%) calculated 18.2% (95% CI: 16.1, 20.3) in females vs 26.3% (95% CI: 22.7, 29.8) in males. Moreover, the obesity prevalence based on WHR was 33.2% (95% CI: 30.7, 35.7) calculated 40.1% (95% CI: 36.6, 43.5) in females vs 21.9% (95% CI: 18.8, 25.0) in males, respectively. Therefore, we considered a subject as obese if he/she had BMI more than 25 or WHR more than 0.9 in males and more than 0.8 in females. According to this definition, 37.2% (41.2% in females vs 30.7% in males) were affected to overweight and obesity. Therefore, the consumption of fast food was related to obesity. Moreover, a significant relationship was observed between obesity and consumption of sandwich (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.4, 2.41), fried chicken (OR: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.22,1.73), and pizza (OR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.1, 2.9). In addition, the fast food consumption was related to WHR as abdominal obesity (OR: 1.46, 95 CI: 1.11, 2.26), but was not related to BMI as general obesity (OR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.63, 1.52) (Tab. III). Based on multivariate regression model (Tab. IV) only marital status, type of university and gender were the most related factors of fast food consumption. Therefore, studying in nongovernmental university (OR: 3.16, 95% CI: 1.8, 5.6), single status (OR: 3.08, 95% CI: 1.26, 5.01) and being females (OR: 2.96, 95% CI: 1.61,4.53) are the most important related factors of fast food consumption, respectively in Qom, Iran.

Tab. III.

The relationship between fast food consumption and obesity in studied subjects.

| Fast food consumption | Obese | Normal | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All type of fast food consumption No Yes |

22 90 |

57 132 |

1.00 1.35 (1.41- 2.41) |

| Sandwich consumption No Yes |

79 100 |

86 32 |

1.00 1.4 (1.22-1.73) |

| Fried chicken consumption No Yes |

87 24 |

169 17 |

1.00 2.74 (1.39-5.37) |

| Fried potato consumption No Yes |

107 4 |

177 9 |

1.00 0.735 (0.22-2.44) |

| Hotdog consumption No Yes |

108 3 |

184 2 |

1.00 1.6 (0.78-3.37) |

| Pizza consumption No Yes |

57 54 |

122 64 |

1.00 1.8 (1.13-2.90) |

| Obesity based on BMI No Yes |

18 46 |

65 172 |

1.00 0.97 (0.63-1.52) |

| Obesity based on WHR No Yes |

21 79 |

55 139 |

1.00 1.46 (1.11-2.26) |

Tab. IV.

Multivariate analysis of predictive factors of fast food consumption in under studied subjects.

| Variables | Beta | SE of beta | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single marital status | 1.12 | 0.453 | 0.013 | 3.08 (1.26-5.01) |

| Nongovernmental university | 1.15 | 0.228 | 0.001 | 3.16 (1.81-5.62) |

| Female gender | 1.08 | 0.312 | 0.001 | 2.96 (1.61-4.53) |

The adjusted variables in this model were job, educational level, field of study and type of university.

Discussion

According to our results, 72.4% and 34% have used at least one type of the fast foods in recent month and recent week, respectively. It seems that the consumption of fast food in Qom students is high due to lack of recreational facilities and entertainment in this religious city. However, the fast food consumption in our study was lower than other studies [4, 20]. Results of studies in students of King Faisal University reported that more than 90% of people used fast foods monthly that was higher our estimate. In addition, a same study in female students aged 18 to 25 years showed that 47.1% had fast food consumption for two or more time per week [5].

The obesity prevalence in our study was estimated 21.3% and 33.2%, based on BMI and WHR, respectively. In a previous study, the obesity/overweight prevalence was 29.7% 5 and nearly half of them used fast foods. Moreover, in Shah et al. study, more than 34% of Chinese medical students were pre-obese and obese [4].

According to our results WHR was significantly different between subjects who used and not used fast food while, the difference in BMI was not significant. Therefore, fast food consumption was related to WHR, but did not related to BMI. In addition, consumption of sandwich, fried chicken and pizza were associated with obesity/overweight based BMI. Same direct association were demonstrated the association between fast food consumption and overweight/obesity in different studies [10, 14, 15, 21, 22]. Fast foods are poor in micronutrients, low in fiber, high energy density, high in glycemic load9 and large portion size with sugar [4] and could be more energetic than the daily energy requirements [6, 9]. In addition, the average energy density of an entire menu in fast food restaurant is approximately more than twice the energy density of a healthy menu [22]. According to some studies [3, 22, 23] obesity is the core of some important non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes [12, 22, 23]. Increase in energy density of diet by fat or sugar, together with concomitant eating behaviors like snacking, binge eating and eating out; promote unhealthy weight gain through passive overconsumption of energy [4, 6].

Fast food consumption is positively related to overweight and obesity due to extremely high energy density of these foods [6, 22]. Moreover, a study a significant association was observed between BMI and fast food consumption [4]. Two commonly eaten fast foods including fried foods and hotdogs have been associated with risk of obesity and weight gain [22]. Moreover, fast food consumption was related to general obesity in female adolescents. Moreover, obesity/overweight was significantly associated with frequency of fast food consumption [5].

This study found the prevalence of obesity was higher in females, while the prevalence of fast food consumption was higher in males. However, male students who are married are more interesting to eating fast food and it might be due to the religious culture of Qom as the most religious city of Iran. In the other hand, the single female students are not free to go in fast food restaurants than married ones. Moreover, three variables including marital status, type of university and gender are the most associated factors of fast food consumption. Based on our results in multivariate model, both studying in nongovernmental University and being single increase the odds of fast food consumption more than three fold. Moreover, female students used fast food 2.9 folds more than male students. The main reasons of students for fast food consumption are taste and comfort to access to these foods and lack of cooking skills [5]. The higher fast foods consumption in females and single students might related to lower wasting time in android social networks than male students [25, 26]. Moreover, since in nongovernmental university the price of kitchen food is high, the students are more interesting to have eating in fast food restaurants. However, the fast food prevalence is high in students and teenagers probably due to low cost [4, 16]. Nevertheless, because comfort accesses to fast food the corresponding expenditures are rising among people [15]. Moreover, the price of health outcomes of consequences of fast food consumption are more expensive and need to more investigations [9, 15].

We could not measure the morphometric characters and adipocity measures of students as other body compositions indexes. Moreover, lack of cooperation of students for anthropometric measurements was another limitation of the current study.

Conclusions

The prevalence of fast food consumption and obesity/overweight in Iranian student is high. Studying in nongovernmental University, being single and females were associated with fast food consumption to three fold. Fast food consumption could have associated to abdominal obesity based WHR to 46%, but was not related to general obesity based on BMI. However, this study showed the different effect of fast foods on abdominal and general obesity as a hypothesis. Future studies need to determine the pure effect of fast food consumption on different dimensions of obesity.

Tab. I.

The relationship between demographic variables and fast food consumption.

| Used fast food | Not-used fast food | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | % | N | % | P value |

| Gender Female Male |

126 92 |

67.4 80.7 |

61 22 |

32.6 19.3 |

0.008 |

| Marital status Single Married |

176 42 |

69.8 85.7 |

76 7 |

30.2 14.3 |

0.015 |

| Job Student Employed |

191 24 |

72.1 66.6 |

74 10 |

27.1 34.4 |

0.547 |

| Education level BSc MSc |

161 56 |

70.0 81.0 |

49 13 |

30.0 19.0 |

0.040 |

| University Governmental Nongovernmental |

94 124 |

62.3 82.7 |

57 26 |

37.7 17.3 |

0.001 |

| Field of education Medical sciences Basic sciences |

161 57 |

70.0 81.4 |

69 13 |

30.0 18.6 |

0.040 |

| Residency place at night Own home Parent’s home University dormitories |

41 126 49 |

78.8 71.6 70.0 |

11 50 21 |

21.2 28.4 30.0 |

0.632 |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research Vice-Chancellor of Qom University of Medical Sciences for financial supporting of this work. They are also grateful students who participated in this study.

Funding source: Qom University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Authors' contributions

AM: contributions to the conception, design of the work; analysis, and interpretation of data and Final approval of article.AA: contributions the acquisition and analysis of data for the work and Drafting the article. EM: contributions to the conception or design of the work; interpretation of data for the work; and Final approval of the article. SA: contributions to the conception or design of the work; interpretation of data for the work; and Final approval of the article. SK: contributions to the conception or design of the work analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and Final approval of the article.HA: contributions to the conception, design of the work; analysis, and interpretation of data and Final approval of article.

References

- [1].Niemeier HM, Raynor HA, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Rogers ML, Wing RR. Fast food consumption and breakfast skipping: predictors of weight gain from adolescence to adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J Adolesc Health 2006;39(6):842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nixon H, Doud L. Do fast food restaurants cluster around high schools? A geospatial analysis of proximity of fast food restaurants to high schools and the connection to childhood obesity rates. J Agric Food Syst Community Dev 2016;2(1):181-94. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Williams J, Scarborough P, Matthews A, Cowburn G, Foster C, Robert N, Rayner M. A systematic review of the influence of the retail food environment around schools on obesity-related outcomes. Obes Rev 2014;15(5):359-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shah T, Purohit G, Nair SP, Patel B, Rawal Y, Shah R. Assessment of obesity, overweight and its association with the fast food consumption in medical students. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8(5):CC05-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Al-Otaibi HH, Basuny AM. Fast food consumption associated with obesity/overweight risk among University female student in Saudi Arabia. Pak J Nutr 2015;14(8):511-6. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dumanovsky T, Huang CY, Nonas CA, Matte TD, Bassett MT, Silver LD. Changes in energy content of lunchtime purchases from fast food restaurants after introduction of calorie labelling: cross sectional customer surveys. BMJ 2011;343:d4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income. Am J Prev Med 2004;27(3):211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: Associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol 2011;9(3):221-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Hom L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR, et al. Fast food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet 2005;365(9453):36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dunn RA, Sharkey JR, Horel S. The effect of fast food availability on fast food consumption and obesity among rural residents: an analysis by race/ethnicity. Econ Hum Biol 2012;10(1):1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Eshrati B, Hasanzadeh J, Beigi AM. Calculation of population atributable burden of excess weight and obesity to non-contagious diseases in Markazi provience of Iran. Koomesh 2010;11(2):83-90. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hassanzadeh J, Mohammadbeigi A, Eshrati B, Moemenbellah-Fard M. Estimation of the regional burden of non-communicable diseases due to obesity and overweight in Markazi province, Iran, 2006-2007. J Cardiovasc Dis 2012;3(1):26-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dunn KI, Mohr P, Wilson CJ, Wittert GA. Determinants of fast food consumption. An application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2011;57(2):349-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jeffery RW, Baxter J, McGuire M, Linde J. Are fast food restaurants an environmental risk factor for obesity? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006;3(1):2 pmid: 16436207, doi:10.1186/1479-5868-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev 2008;9(6):535-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Park S, Choi BY, Wang Y, Colantuoni E, Gittelsohn J. School and Neighborhood Nutrition Environment and Their Association With Students’ Nutrition Behaviors and Weight Status in Seoul, South Korea. J Adolesc Health 2013;53(5):655-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nelson MC, Lytle LA. Development and Evaluation of a Brief Screener to Estimate Fast food and Beverage Consumption among Adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109(4):730-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sengupta P. Capsulation of the global fitness status and body composition of the young Toto women: The smallest tribal community of India. Perform Enhanc Health 2016;5(1):4-9. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sengupta P, Krajewska-Kulak E. Evaluation of physical fitness and weight status among fisherwomen in relation to their occupational workload. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2014;4(4):261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fazelpour S, Baghianimoghadam M, Nagharzadeh A, Fallahzadeh H, Shamsi F, Khabiri F. Assessment of fast food concumption among people of Yazd city. Toloo-e-Behdasht 2011;10(2):25-34. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fung C, McIsaac J-LD, Kuhle S, Kirk SFL, Veugelers PJ. The impact of a population-level school food and nutrition policy on dietary intake and body weights of Canadian children. Prev Med 2013;57(6):934-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Fast foods and risk of chronic diseases. J Res Med Sci 2008;13(1):1-2. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Golzarand M, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Azizi F. Fast food consumption in Iranian adults; dietary intake and cardiovascular risk factors: tehran lipid and glucose study. Arch Iran Med 2012;15(6):346-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thompson OM, Ballew C, Resnicow K, Must A, Bandini LG, Cyr H, Dietz WH. Food purchased away from home as a predictor of change in BMI z-score among girls. Int J Obes 2003;28(2):282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mohammadbeigi A, Absari R, Valizadeh F, Saadati M, Sharifimoghadam S, Ahmadi A, Mokhtari M, Ansari H. Sleep quality in medical students; the impact of over-use of mobile cell-phone and social networks. J Res Health Sci 2016;16(1):46-50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mohammadbeigi A, Mohammadsalehi N, Moshiri E, Anbari Z, Ahmadi A, Ansari H. The prevalence of phantom vibration/ringing syndromes and their related factors in Iranian students of medical sciences. Asian J Psychiatr 2017;27:76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]