Significance

Debate about regulation of industrial polluters often concerns a presumed trade-off between negative pollution impacts and positive employment opportunities. These arguments are especially sensitive among communities of racial/ethnic minorities, who disproportionately suffer exposure to pollution and lack access to high-quality employment. We combine US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data on toxics exposure with Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) data on employment to examine how the racial/ethnic distribution of industrial employment corresponds to the distribution of exposure to air toxics emitted by the same facilities. The share of pollution risk accruing to minority groups generally exceeds their share of employment and greatly exceeds their share of higher paying jobs. In aggregate, we find no evidence that facilities that create higher pollution risk for surrounding communities provide more jobs.

Keywords: environment, employment, pollution, disparities

Abstract

Proximity to industrial facilities can have positive employment effects as well as negative pollution exposure impacts on surrounding communities. Although racial disparities in exposure to industrial air pollution in the United States are well documented, there has been little empirical investigation of whether these disparities are mirrored by employment benefits. We use facility-level data from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) and the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission EEO-1 database to assess the extent to which the racial and ethnic distribution of industrial employment corresponds to the distribution of exposure to air toxics emitted by the same facilities. The share of pollution risk accruing to minority groups generally exceeds their share of employment and exceeds their share of higher paying jobs by a wide margin. We find no evidence that facilities that create higher pollution risk for surrounding communities provide more jobs in aggregate.

Population exposure to industrial pollutants is often characterized as a social cost that brings the benefit of industrial employment opportunities. The present study examines whether such a link exists between pollution and jobs for racial and ethnic minorities in the United States.

It is well documented that racial and ethnic minorities in the United States experience disproportionate exposure to toxics air emissions from industry (1, 2). The reasons for this have been a matter of debate: Some identify discriminatory siting of hazards in vulnerable communities, while others suggest postsiting demographic changes in response to lower property values or greater employment opportunities (3, 4). Multivariate analysis finds race/ethnicity to be a significant predictor of exposure even after controlling for income (1, 5), which casts doubt on postsiting population sorting as a sufficient explanation. Longitudinal analysis has found that new hazardous facilities tend to be sited disproportionately in what were already predominantly minority communities (6, 7).

Regardless of the mix between siting and sorting as explanations, the alignment of environmental disparities with employment patterns is of interest. If racial and ethnic minorities experience employment gains that mirror their disproportionate pollution burdens, local policymakers and communities might face a trade-off in deciding how to regulate polluting facilities or whether to accept new ones (8–11). It would also lend weight to employment opportunities as a plausible reason for postsiting demographic changes. If, on the other hand, there is little empirical relationship between the environmental costs and employment benefits, then the importance of establishing a normative trade-off is reduced.

In 2002, members of Congress asked the Government Accountability Office (GAO) for a study of the economic impacts of industrial facilities that had been subjects of federal or state agency complaints that they expose minority communities to greater environmental risk than the general population. The resulting report (12) presented data on employment obtained from 15 selected facilities but not on how many people were hired at different salary levels nor whether employees resided in nearby communities. The report notes that local organizations “told us that, in their view, the majority of jobs filled by community residents were low paying.” In a comment on the GAO study, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Office of Civil Rights recommended analysis of more detailed information on number and types of jobs provided to communities nearest polluting facilities. The present study is an effort to do this.

At the facility level, we merge employment data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)’s EEO-1 database with air pollution data from the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) and Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI). We select the nation’s top 1,000 polluting facilities, which together account for 94.5% of aggregate human health risk of air pollution from TRI-reporting facilities as measured by RSEI scores, on the grounds that these are the most important sites at which to compare racial and ethnic distributions of exposure and employment.

Data Sources

The EEO-1 Data.

Authorized under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, EEO-1 requires all firms with at least 100 employees (50, for Federal contractors) to report counts of employees by 7 ethnicity/race groups, by sex, and by 10 occupation categories (13, 14). The data are used to monitor compliance with Federal antidiscrimination rules. Researchers have used EEO-1 data to analyze impacts of affirmative action policies (15, 16). We use EEO-1 data for 2010, provided to us by the EEOC with confidentiality provisions that do not permit us to identify publicly the names of specific facilities or firms. There are ∼680,000 records in the complete dataset, each representing one establishment.

The TRI and RSEI Data.

TRI was created at the direction of Congress under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986, which requires all industrial facilities in specified sectors that meet activity thresholds to submit annual data to the EPA on deliberate and accidental releases of some 600 toxic chemicals into the air, surface water, and the ground (17). In 2010, 14,815 TRI-reporting facilities released a total of 858 million pounds of these chemicals into the air; an additional 178 million pounds were transferred offsite to incinerators, of which the EPA estimates that postincineration air releases amounted to ∼1.8 million pounds.

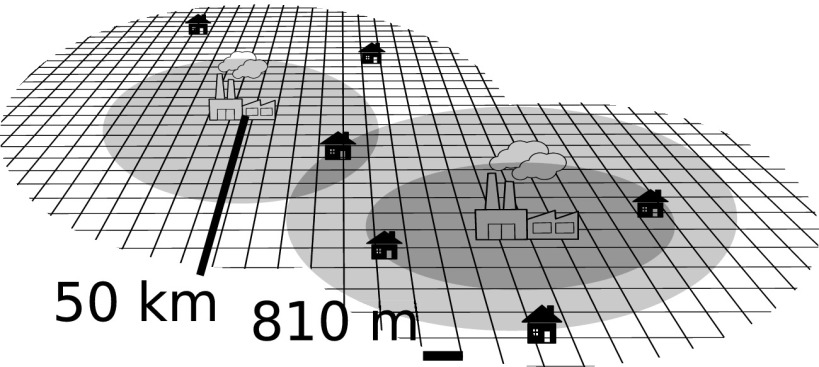

The TRI simply reports the mass of releases for different chemicals, whose pound-for-pound inhalation toxicity varies by up to seven orders of magnitude. The EPA launched the RSEI project in the mid-1990s to add value to TRI data by incorporating toxicity weights, a fate-and-transport model, and population exposure (18). The toxicity weights are based on peer-reviewed databases from multiple sources. RSEI toxicity weights establish comparability in potential chronic human health risk between different chemicals and quantities of airborne toxic industrial releases. Fig. 1 provides a schematic of the RSEI Gaussian plume model, which estimates the concentration of each chemical within a 50-km radius around each releasing facility.

Fig. 1.

EPA’s RSEI: Schematic of air plume model.RSEI scores potential chronic human health risk by estimating toxicity-weighted concentrations of TRI releases in a 50-km radius around facilities at 810 m 810 m resolution. Number and race of exposed residents are from US Census (19–21).

RSEI overlays toxicity-weighted air pollution concentrations on a population grid drawn from block-level data from the US Census. The RSEI score represents the aggregate human health risk borne by the population living within 50 km of the facility. EPA and state environmental agencies use RSEI to set priorities for compliance and enforcement actions. The distribution of RSEI scores across TRI-reporting facilities is highly skewed, with the top 1,000 facilities accounting for almost 95% of the total score nationwide.

RSEI–Geographic Microdata (RSEI-GM) provide grid cell-level data on exposures that are aggregated to create facility-level scores. The EPA makes these data available to researchers (21). By spatially merging RSEI-GM data with Census data on race, ethnicity, and income, researchers have analyzed the environmental justice dimensions of industrial pollution (1, 5, 18, 19, 22–28).

We were able to match across the EEO-1 and TRI databases a total of 712 facilities (of the top 1,000 polluters), following the methods described in Materials and Methods. Together these facilities account for 68% of the total RSEI score for all 14,815 facilities reporting TRI air releases nationwide.

Results

Comparison of Exposure and Employment Distributions.

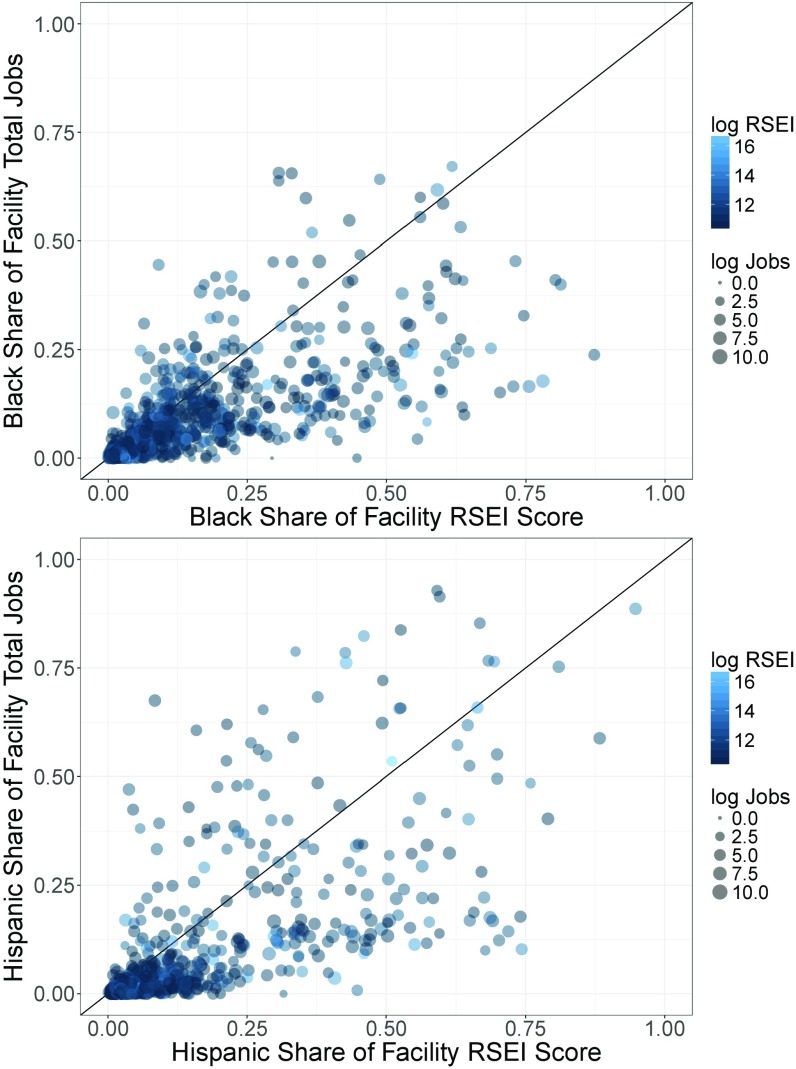

Fig. 2, Upper and Lower depict the shares of employment (vertical) and air-pollution exposure (horizontal) for blacks and Hispanics. The share of air pollution exposure refers to aggregate burden borne by all black or Hispanic people within a 50-km radius of the facility. The share of employment refers to jobs at the facility held by black or Hispanic people. The 45° line is the relationship that would be obtained if population exposure and facility employment shares were identical. Visual inspection shows that the exposure shares of both population subgroups generally exceed their employment shares, often by a substantial margin.

Fig. 2.

Jobs versus toxics risk for African Americans and Hispanics. Upper shows the share of jobs (vertical) versus share of the facility’s total potential chronic human health risk (horizontal) for African Americans. Lower presents the same relationship for Hispanics. Point size indicates the number of jobs provided by the facility; shading indicates the total human health risk generated by the facility.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics. For blacks, the mean share of exposure is 17.4% and the mean share of employment is 10.8%—a disparity of 6.6 percentage points. For Hispanics, the corresponding shares were 15.0% and 9.8%, a disparity of 5.2 percentage points. At 312 facilities (44% of the total), the black share of exposure is more than twice as high as the black share of employment; the reverse (employment share more than double exposure share) is true at only 40 facilities (5.6% of the total). For Hispanics, the corresponding numbers are 442 (62.1%) and 40 (5.6%).

Table 1.

Share of jobs and share of risk, by race

| Summary statistics | African Americans | Hispanics |

| Share of exposure | 0.174 (0.006) | 0.150 (0.006) |

| Share of jobs | 0.108 (0.004) | 0.098 (0.006) |

| Disparity | 0.068 (0.008) | 0.052 (0.009) |

| Facilities for which ratio of job share to exposure share | ||

| <0.5 | 312 | 442 |

| >2 | 40 | 40 |

| Total number of facilities | 712 | 712 |

The upper rows report facility means for the shares of toxic exposure and shares of jobs for African Americans and Hispanics and the disparity between exposure and jobs. Standard errors in parentheses. The lower rows report the number of facilities for which the ratio of job share to exposure share is less than 0.5 (i.e., relatively few jobs come at the expense of high exposure) or more than 2 (i.e., relatively many jobs come with high exposure).

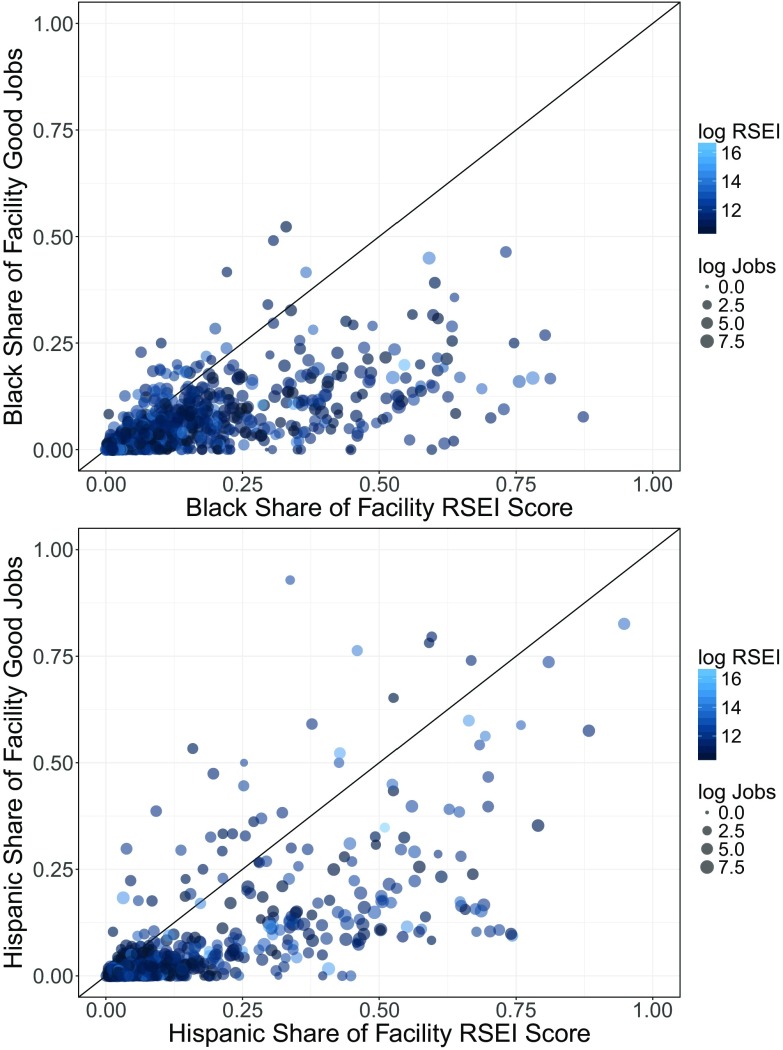

Fig. 3 presents comparable data for skilled and professional workers, who on average account for 60% of employment at these facilities. For this subset of jobs, the discrepancies are larger than for total employment. The mean shares of better jobs held by blacks and Hispanics were 6.9% and 6.8%, respectively; at more than half of the facilities, the black and Hispanic shares of better employment were less than half their shares of pollution exposure.

Fig. 3.

Good jobs versus toxics risk for African Americans and Hispanics. Upper shows the share of good jobs held by African Americans at the facility (vertical) versus the African American share of the facility’s total potential chronic human health risk (horizontal). Lower presents the same relationship for Hispanics. Point size indicates the number of good jobs provided by the facility; shading indicates the total human health risk generated by the facility.

Employment by race represents the benefits by race in the area of pollution exposure. Of course, not all persons of a given race benefit from the employment of people of that race. Furthermore, some workers employed at the facility may not live in the 50-km radius for which community exposure is assessed. The association of communities affected by employment and those affected by pollution is thus imperfect. Census data on commuting indicate that mean travel time to work is roughly 25 min with relatively little variation in means by industry (29), which suggests that much of an industrial workforce typically lives within 50 km of the facility. However, as the minority beneficiaries of employment and minority bearers of the burden of exposure are not necessarily the same people, the estimated disparity provides a lower bound estimate of cost without benefit.

Exposure–Employment Disparities by Industrial Sector.

The difference between the exposure and employment shares of blacks and Hispanics combined provides an indicator of overall racial and ethnic disparity. For all facilities, the average exposure share for the two subgroups combined is 32.6%, and the average employment share is 21.3%. Table 2 presents sectoral disparities for industrial sectors with 15 or more facilities in our matched dataset. The widest disparity occurs in petroleum and coal products manufacturing (a sector that includes refineries) where blacks and Hispanics in neighboring communities receive 47.9% of pollution exposure and 21.6% of total jobs.

Table 2.

Disparity between risk share and job share, by industrial sector

| Minority share of | Toxicity disparity with | ||||

| Industrial sector | Toxicity | Jobs | Good jobs | Jobs | Good jobs |

| Petroleum and coal prods | 0.479 | 0.216 | 0.171 | 0.263 | 0.308 |

| Chemicals | 0.419 | 0.186 | 0.145 | 0.233 | 0.274 |

| Paper | 0.248 | 0.144 | 0.079 | 0.104 | 0.169 |

| Fabricated metal prods | 0.316 | 0.246 | 0.148 | 0.070 | 0.168 |

| Machinery | 0.219 | 0.107 | 0.065 | 0.112 | 0.154 |

| Primary metals | 0.283 | 0.224 | 0.136 | 0.059 | 0.147 |

| Nonmetallic mineral prods | 0.260 | 0.230 | 0.126 | 0.030 | 0.134 |

| Transportation equipment | 0.271 | 0.225 | 0.150 | 0.046 | 0.121 |

| Utilities | 0.212 | 0.102 | 0.096 | 0.110 | 0.116 |

| Other industries | 0.299 | 0.265 | — | 0.033 | — |

| All industries | 0.326 | 0.213 | 0.135 | 0.113 | 0.191 |

Columns 1–3 report the minority (African American and Hispanic) share of the toxicity risk, jobs, and good jobs for all facilities in each industry. Columns 4 and 5 report the difference between the minority share of the toxicity risk burden and the minority shares of jobs and good jobs. The named industries are those with at least 15 facilities among the 712 in the study.

Impact of Exposure Share on Employment Share.

We regress the black or Hispanic share of facility employment on exposure share, with and without controls for population share in the county of the facility. For blacks, one additional percentage point in the share of pollution exposure is associated with only a 0.46% point increase in employment share—that is, the slope of the simple regression line is less than half the 45° slope in Fig. 2, Upper. When we control for the black share of county population, a variable that proxies for the local job-market availability of black employees, the estimated coefficient on exposure share declines to 0.26. The reduced coefficient indicates that, controlling the composition of the local population, additional exposure of African Americans is associated with little additional employment opportunities. For better paid jobs, the estimated coefficients are lower at 0.27 and 0.14 (Table 3, upper portion).

Table 3.

Share of jobs versus share of toxics risk

| Jobs | Better jobs | |||

| Regression results | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Black share | ||||

| Intercept | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | 0.01*** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Black toxic share | 0.46*** | 0.26*** | 0.27*** | 0.14*** |

| (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| County percent black | 0.33*** | 0.23*** | ||

| (0.04) | (0.03) | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.45 |

| Hispanic share | ||||

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Hispanic toxic share | 0.64*** | 0.25*** | 0.50*** | 0.13** |

| (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| County percent Hispanic | 0.63*** | 0.59*** | ||

| (0.08) | (0.06) | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.53 |

| Observations | 712 | 712 | 712 | 712 |

Each column shows the coefficients from a linear regression of the share of jobs on the share of risk for Africa Americans (upper portion) and Hispanics (lower portion). Standard errors are in parentheses. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

For Hispanics, we obtain somewhat higher coefficients than for blacks (although still well below 1.0) without the county controls and coefficients very similar to those for African Americans when we control for the county population share of the ethnic minority (Table 3, lower portion).

Relationship Between Total Employment and Pollution Risk.

While the facilities analyzed here rank among the top 1,000 nationwide in human health risk from air toxics releases as measured by the RSEI score, their scores vary by up to three orders of magnitude. We examine the relationship between employment and pollution risk among these facilities—a universe of special importance because together these facilities account for more than two-thirds of the total human health risk from air toxics releases from all TRI facilities nationwide.

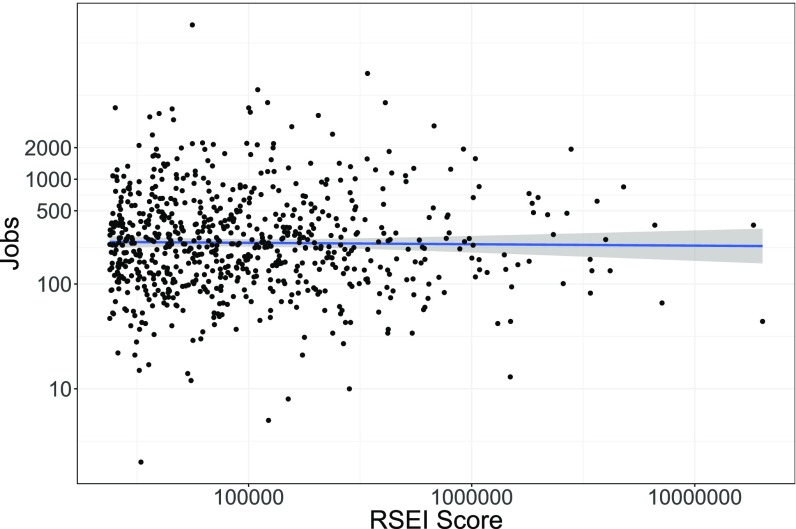

Fig. 4 shows the relationship between a facility’s total pollution risk and total number of jobs. Both pollution risk (horizontal) and jobs (vertical) are shown on logarithmic scales, and a locally smoothed regression line shows the relationship between the two. At the national level, there is no evident trade-off between pollution risk and the number of jobs.

Fig. 4.

Jobs versus pollution risk. Facility employment (vertical) versus RSEI score (horizontal). Log scales. Smoothed with general additive model.

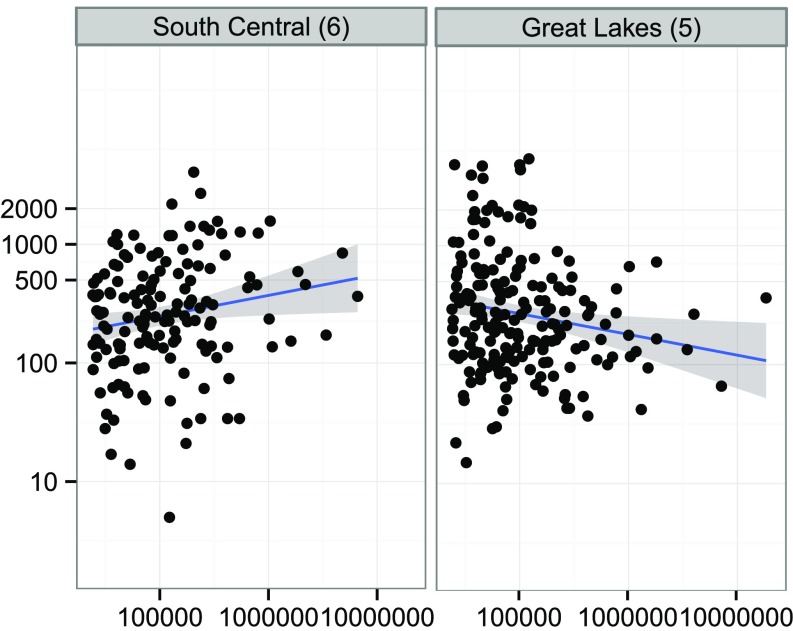

A more mixed picture emerges at the regional level, which is consistent with the variation in regional patterns of environmental disparity (1). Fig. 5 presents comparable plots for the two EPA regions with the largest number of facilities: South Central (6) and Great Lakes (5). In South Central, facilities generating more pollution risk tend to provide more jobs, while in the Great Lakes, as pollution risk increases, jobs actually go down. These results suggest that regional policymakers and regulators may face different jobs versus pollution trade-offs. Scatterplots for all regions and for most large industries are reported in SI Appendix.

Fig. 5.

Jobs versus pollution risk, EPA regions 5 and 6. Facility employment (vertical) versus RSEI score (horizontal). Log scales. Smoothed with general additive model.

Table 4 presents estimates of the elasticity of employment with respect to pollution risk. The first two columns report national estimates, with and without state and sector dummies. The elasticities are close to zero. The inclusion of industry dummies in column 2 in particular indicates that there is essentially no relationship between facility jobs and population pollution risk even within narrowly defined industrial categories. The third and fourth columns report estimates for the South Central and Great Lakes regions, respectively. A 10% increase in pollution risk is associated in the South Central region with a 1.8% increase in the number of jobs and in the Great Lakes region with a 1.7% decrease in the number of jobs. These are the only two EPA regions for which the estimated elasticities were statistically significantly different from zero. Comparable estimates for better paying jobs show similar results.

Table 4.

Total jobs and pollution risk: Elasticity estimates

| National | ||||

| Regression results | (1) | (2) | South Central | Great Lakes |

| Log(RSEI score) | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.18* | −0.17* |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.08) | (0.07) | |

| Intercept | 5.67*** | 5.76*** | 3.48*** | 7.60*** |

| (0.41) | (1.11) | (0.93) | (0.81) | |

| State dummies | Yes | |||

| Industry dummies | Yes | |||

| Adjusted | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Observations | 712 | 712 | 147 | 195 |

Each column shows the coefficients from a linear regression of log employment on the log total population risk for each facility. In columns 3 and 4, the sample is limited to facilities in South Central (EPA region 6) and the Great Lakes (EPA region 5). Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

Disproportionate exposure of blacks and Hispanics to industrial air pollution in the United States may be caused by discriminatory siting decisions by firms, discriminatory zoning or regulatory policies by government agencies, or postsiting demographic changes in response to economic incentives (such as changes in property values or employment opportunities) or discriminatory practices in housing or mortgage markets. Regardless of the relative strength of alternative explanations for environmental disparities on racial and ethnic lines, it is of interest to know to what extent exposure is accompanied by industrial employment gains.

By matching data from the EEOC and EPA, we have examined this question for 712 facilities that together generate more than two-thirds of the human health risk from industrial air toxics releases in the United States and are representative of the facilities that generate 95% of human health risk from industrial air toxics. Comparing the distribution of pollution exposure risk to the distribution of total jobs and better paid jobs, we find that the share of exposure risk borne by blacks and Hispanics generally exceeds their share of employment at the polluting facilities, often by a substantial margin. On average, blacks receive 17.4% of the exposure risk but hold only 10.8% of the jobs and 6.9% of higher paying better jobs. Similarly, Hispanics receive 15.0% the exposure risk but hold only 9.8% of the jobs and 6.8% of better jobs. The largest difference between exposure and employment shares is found in the petroleum and coal products manufacturing sector, where the share of exposure risk borne by blacks and Hispanics is more than double their share of jobs.

Variation across facilities shows that higher minority shares of exposure are not matched by correspondingly higher employment shares. For blacks, a 1 percentage point increase in exposure share is associated with a 0.46 percentage point increase in their share of jobs; for Hispanics, the corresponding figure is 0.64 percentage point. In other words, disproportionate exposure is only weakly associated with employment gains for blacks and Hispanics.

Turning to the relation between total jobs per facility and the human health risk posed by the facility’s air toxics releases, we find no evidence for a widespread trade-off between jobs and pollution. Nationwide, we find zero correlation between these variables. The two EPA regions with the largest numbers of facilities yield statistically significant but opposite results. For policymakers and regulators, these results suggest that a jobs-versus-pollution trade-off is the exception, not the rule, and that even where the elasticity is negative its magnitude is modest at –0.17. This finding is consistent with those of studies that have examined the relationship between employment and environmental regulation by comparing locations and industrial sectors, which have reported either small trade-offs or positive impacts of regulation on employment (30–33).

Our analysis provides a cross-sectional analysis of the relationship between employment opportunities and pollution exposure. Both the costs of exposure and the benefits of employment have long-term consequences, and the relationship—that is, the trade-off or the absence of a trade-off—may be changing over time. Additional studies using data for longer periods will be useful in shedding further light on the exposure–employment relationship.

To consider recruiting, regulating, or even shutting down facilities, policymakers need empirical data on how many jobs and how much pollution are associated with existing and potential facilities. Policymakers may also seek to apply a normative weighting system for converting pollution and jobs into a commensurate metric, but here we simply empirically assess the relationship without addressing what quantity of jobs would mitigate or compensate threats to population health. Given our finding of no systematic trade-off, the question of commensurability may be diminished in importance. These results cast doubt on the proposition that stricter environmental regulation and the pursuit of environmental justice would come at a cost to employment either in aggregate or for racial and ethnic minorities.

Materials and Methods

EEO-1 and RSEI provide facility-level data but use different facility identification codes. Facilities were matched across databases with information on firm and establishment name, address, geolocation, and Dun & Bradstreet numbers. Matching was undertaken by database methods followed by a record-by-record review for all 1,000 facilities in the RSEI sample. When a TRI facility comprises more than one EEO-1 establishment, we aggregated the EEO-1 establishments to correspond to a single TRI facility.

Due to our interest in assessing trade-offs between pollution and employment in facilities whose air emissions have substantial human health impacts, our target sample was the 1,000 facilities with the highest RSEI air pollution scores. In cases where facilities revised their 2010 TRI reports to show a lower mass of release of one or more chemicals, we adjusted the RSEI data by assuming a linear relation between mass and score for the release in question. Two facilities were dropped from the original sample for this reason. We successfully matched 712 of the top TRI facilities ranked by RSEI score to EEO-1 data.

SI Appendix presents summary statistics and distributions for 712 EEO-matched and 288 unmatched facilities in the top 1,000 polluting RSEI facilities. The matched sample closely resembles the unmatched sample in terms of regional and sectoral distribution as well as means and variation of RSEI scores. Together the 712 facilities account for 72.2% of the RSEI score of the top 1,000 facilities and 68.2% of the total RSEI score for all 14,815 TRI facilities nationwide reporting air releases in 2010.

We designate better paid jobs in the EEO-1 data as the following occupational categories: Executive/Senior Level Officials and Managers, First/Mid-Level Officials and Managers, Professionals, Technicians, and Craft Workers. Together these account for 60% of total jobs in the 712 facilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ronald Edwards, Director, Surveys Division, US EEOC, provided the EEO-1 data and Dr. Lynne Blake-Hedges, Senior Economist, Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, US EPA, provided the RSEI data. Rich Puchalsky and Kenyon Kowalski provided research assistance. The Indiana University Pervasive Technology Institute provided High Performance Computing database, storage, and consulting resources. This work was supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from National Science Foundation Grant DBI-1052875.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. V.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1721640115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zwickl K, Ash M, Boyce JK. Regional variation in environmental inequality. An analysis of industrial air toxics exposure disparities by income, race and ethnicity in US cities. Ecol Econ. 2014;107:494–509. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohai P, Pellow D, Roberts JT. Environmental justice. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2009;34:405–430. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Been V, Gupta F. Coming to the nuisance or going to the barrios? A longitudinal analysis of environmental justice claims. Ecol Law Q. 1997;24:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Been V. Locally undesirable land uses in minority neighborhoods: Disproportionate siting or market dynamics? Yale Law J. 1994;103:1383–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash M, Robert Fetter T. Who lives on the wrong side of the environmental tracks? Evidence from the EPA’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators model. Soc Sci Q. 2004;85:441–462. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohai P, Saha R. Which came first, people or pollution? A review of theory and evidence from longitudinal environmental justice studies. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10:125011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pastor M, Sadd J, Hipp J. Which came first? Toxic facilities, minority move-in, and environmental justice. J Urban Aff. 2001;23:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belova A, Gray WB, Linn J, Morgenstern RD. 2013. Environmental Regulation and Industry Employment: A Reassessment (US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, Washington, DC), Research Paper No. CES-WP-13-36.

- 9.Greenstone M, List JA, Syverson C. 2012. The Effects of Environmental Regulation on the Competitiveness of Us Manufacturing (National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA), Technical report.

- 10.List JA, Millimet DL, Fredriksson PG, McHone WW. Effects of environmental regulations on manufacturing plant births: Evidence from a propensity score matching estimator. Rev Econ Stat. 2003;85:944–952. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenstone M. The impacts of environmental regulations on industrial activity: Evidence from the 1970 and 1977 clean air act amendments and the census of manufactures. J Polit Economy. 2002;110:1175–1219. [Google Scholar]

- 12.General Accounting Office 2002. Community investment: Information on selected facilities that received environmental permits (General Accounting Office, Washington, DC), Technical Report GAO-02-479, Report to Congressional Requesters.

- 13.Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 2016 EEO-1: Legal basis for requirements. Available at www.eeoc.gov/employers/eeo1survey/legalbasis.cfm. AccessedSeptember 13, 2018.

- 14.Edwards R, Cartwright B, Kyne B. 2007. Employer information report (EEO-1): Data overview. Kauffman Symposium on Entrepreneurship and Innovation Data [U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Office of Research, Information and Planning (ORIP), Washington, DC], 20507, 2007.

- 15.Kurtulus FA. The impact of affirmative action on the employment of minorities and women: A longitudinal analysis using three decades of EEO-1 filings. J Policy Anal Manage. 2016;35:34–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonard JS. The impact of affirmative action on employment. J Labor Econ. 1984;2:439–463. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Environmental Protection Agency 2016 Toxic Chemical Release Inventory reporting forms and instructions, Revised 2016 Version. Section 313 of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (Title III of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986), 12. Available at https://ofmpub.epa.gov/apex/guideme_ext/guideme_ext/guideme/file/ry_2016_form_r.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2018. [PubMed]

- 18.Bouwes NW, Hassur S, Shapiro M. Information for empowerment: The EPA’s risk-screening environmental indicators project. In: Boyce JK, Shelley BG, editors. Natural Assets: Democratizing Environmental Ownership. Island Press; Washington, DC: 2003. pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ash M, Boyce K. Measuring corporate environmental justice performance. Corporate Soc Responsib. Environ Manag. 2011;18:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ash M, et al. Justice in the Air: Tracking Toxic Pollution from America’s Industries and Companies to Our States, Cities and Neighborhoods. Political Economy Research Institute, Amherst, MA; and Program in Environmental and Regional Equity; Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Environmental Protection Agency 2004 Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics, Washington, DC). Available at www.epa.gov/oppt/rsei. Accessed February 1, 2015. [PubMed]

- 22.Boyce JK, Zwickl K, Ash M. Measuring environmental inequality. Ecol Econ. 2016;124:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins MB, Munoz I, JaJa J. Linking ‘toxic outliers’ to environmental justice communities. Environ Res Lett. 2016;11:015004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ard K. Trends in exposure to industrial air toxins for different racial and socioeconomic groups: A spatial and temporal examination of environmental inequality in the US from 1995 to 2004. Soc Sci Res. 2015;53:375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ash M, Boyce JK, Chang G, Scharber H. Is environmental justice good for white folks? Industrial air toxics exposure in urban America. Soc Sci Q. 2013;94:616–636. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohai P, Kweon B-S, Lee S, Ard K. Air pollution around schools is linked to poorer student health and academic performance. Health Aff. 2011;30:852–862. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastor M, Morello-Frosch R, Sadd J. Air Pollution and Environmental Justice: Integrating Indicators of Cumulative Impact and Socio-Economic Vulnerability into Regulatory Decision-Making. California Environmental Protection Agency, Air Resources Board, Research Division; Sacramento, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downey L, Hawkins B. Race, income, and environmental inequality in the United States. Sociol. Perspect. 2008;51:759–781. doi: 10.1525/sop.2008.51.4.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenzie B, Rapino M. Commuting In the United States: 2009. Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollin R. Greening the Global Economy. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bezdek RH, Wendling RM, DiPerna P. Environmental protection, the economy, and jobs: National and regional analyses. J Environ Manage. 2008;86:63–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodstein E, Hodges H. Polluted data: Overestimating environmental costs. Am Prospect. 1997;35:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodstein E. Jobs or the environment? No trade-off. Challenge. 1995;38:41–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.