Abstract

The importance of early detection of autism spectrum disorder followed by early intervention is increasingly recognized. This quasi-experimental study evaluated the long-term effects of a program for the early detection of autism spectrum disorder (consisting of training of professionals and use of a referral protocol and screening instrument), to determine whether the positive effects on the age at referral were sustained after the program ended while controlling for overall changes in the number of referrals. Before, during, and after the program, the proportion of children referred before 3 years (versus 3–6 years) of age was calculated for children subsequently diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (N = 513) or another, non-autism spectrum disorder, condition (N = 722). The odds of being referred before 3 years of age was higher in children with autism spectrum disorder than in children with another condition during the program than before (3.1, 95% confidence interval: 1.2–7.6) or after (1.7, 95% confidence interval: 1.0–3.0) the program but was not different before versus after the program. Thus, although the program led to earlier referral of children with autism spectrum disorder, after correction for other referrals, the effect was not sustained after the program ended. This study highlights the importance of continued investment in the early detection of autism spectrum disorder.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, early detection, implementation, long term, screening

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be reliably diagnosed before 3 years of age and the diagnosis is remarkably stable in both clinical (Kleinman et al., 2008; Lord et al., 2006; Van Daalen et al., 2009) and high-risk samples (Brian et al., 2015; Ozonoff et al., 2015). Over the last years, findings have emphasized the importance of early identification and treatment of ASD to children’s adaptive, social, and cognitive functioning (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015a). Because of the dynamic and plastic nature of the brain, very early interventions may alter the course of brain and behavioral development in children with ASD (Webb et al., 2014), and recent studies have provided evidence of the long-term effectiveness of early interventions (Estes et al., 2015; Pickles et al., 2016). In addition, family and society costs for subsequent professional services may be reduced (Penner et al., 2015; Peters-Scheffer et al., 2012).

Despite the benefits of early detection, the mean age at diagnosis in daily clinical practice still lies around the late preschool years or even later. A review of 42 studies published from January 1999 through March 2012 found that the mean age ranged from 38 to 120 months (Daniels and Mandell, 2014). In order to lower the age at diagnosis, strategies for the early detection of ASD have been developed and promising results have been obtained in some non-randomized studies, showing positive effects on age at diagnosis (Chakrabarti et al., 2005; Holzer et al., 2006; Koegel et al., 2006), percentage of early identified ASD cases (Swanson et al., 2014), and self-efficacy of primary care providers (Mazurek et al., 2017). In a study that used a control region, Oosterling et al. (2010) examined the effect of a screening approach for the early detection of ASD that was integrated in routine developmental surveillance in a specific region of the Netherlands. This early detection program involved (a) training of primary care providers to recognize early signs of autism, (b) use of a specially designed referral protocol that included the Early Screening of Autistic Traits (ESAT) questionnaire (Dietz et al., 2006; Swinkels et al., 2006), and (c) formation of a multidisciplinary diagnostic team at the regional psychiatric academic center. After implementation of the screening program, the mean age at ASD diagnosis decreased significantly by 19.5 months to an average of 63.5 months. In the control region (without active investment in early detection of ASD), the mean age at diagnosis did not change significantly. Although this study provided valuable insight into strategies to improve the early detection of ASD, the question remained whether positive effects are sustained in the long term.

To our knowledge, only one study has investigated the long-term effects of an early detection program (Holzer et al., 2006). This non-randomized study examined the effects of a 2-year program which contained the following aspects: (a) familiarizing primary care providers with early developmental problems, (b) informing pediatricians and general health practitioners about a screening tool (Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT); Baron-Cohen et al., 1996), and (c) performing a diagnostic assessment by a child neurologist, child psychiatrist, and/or child psychologist. With the program, the mean age at diagnosis decreased by 1.5 years, but this effect was not sustained after the program ended. These findings emphasize the importance of a maintenance strategy. Additional understanding of long-term effects can be useful to help policymakers in developing effective programs that will have a permanent effect.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the sustainability of the integrated early detection program developed by Oosterling et al. (2010). The age at referral was recorded of children (aged 0–6 years) subsequently diagnosed with ASD (N = 513) or a non-ASD condition (N = 722) before, during, and after the early detection program. The program ended when financial and staffing support ended, which affected the training of primary care personnel in the recognition of the early signs of ASD and in use of the referral protocol. The multidisciplinary diagnostic team continued to function. We wanted to determine whether the positive effect on age at referral was sustained after the program ended.

Methods

Study design and setting

To facilitate the early detection of ASD in the Netherlands, our group used an integrated early detection program (Oosterling et al., 2010), which was approved by the Dutch Ethical Committee. In the current follow-up study, we performed a natural examination of the age at referral before (January–December 2003), during (January 2004–December 2006), and 2 years after (January 2009–December 2011) the early detection program. Even after the early detection program ended, the multidisciplinary diagnostic team at Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Centre continued to provide highly specialized mental healthcare for infants and toddlers in the region. However, the lack of funding and staff meant that no specific effort was put into training primary care providers to use the screening protocol, including the ESAT. The control region was not included in this follow-up study because we did not receive permission from one of the institutions to use their data.

This study must be viewed in the context of the healthcare setting in the Netherlands. In general, children of all ages can be referred to psychiatric assessment centers by general practitioners, medical specialists (e.g. neurologist or pediatrician), professionals from other mental health services or institutions for language development, and primary care providers. Primary care providers can be the doctors of well-baby clinics or members of specific infant–toddler development teams. These independent infant–toddler development teams work in close collaboration with the doctors and nurses of well-baby clinics and provide parents who may have specific concerns about their child’s development with easily accessible first-line care. They also carry out case management, investigate children’s developmental problems in general, and when necessary, refer children to secondary or tertiary health services for diagnostic assessment and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, no changes in the healthcare policies or healthcare system (e.g. referral strategies) occurred during the time frame of the study.

Participants

The sample included N = 1235 infants, toddlers, and preschoolers (aged 0–6 years) who were referred for clinical psychiatric evaluation before (N = 119), during (N = 531), or after (N = 585) the early detection program was implemented. Of these, 38%, 47%, and 37% were newly diagnosed with ASD as compared to non-ASD diagnoses, respectively. Children with a non-ASD diagnosis had other diagnoses (including absence of a psychiatric diagnosis). This group reflected the general population of referrals in Dutch child and adolescent psychiatry settings, including two-thirds of the non-ASD referrals having externalizing problems and a minority having internalizing or other problems (see Table 1 for more demographics).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by time point for the total sample (N = 1235).

| Before (N = 119) 2003 | During (N = 531) 2004–2006 | After (N = 585) 2009–2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) (%) | Mean (SD) (%) | Mean (SD) (%) | |

| Age at referral (years) | 4.1 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.5) |

| Male | 75.6 | 74.8 | 77.1 |

| Diagnosis ASD | 37.8 | 47.1 | 37.3 |

ASD: autism spectrum disorder; SD: standard deviation.

Early detection program

The early detection program comprised three components: (a) training of primary care providers to recognize early signs of autism, (b) use of a systematic screening protocol including the ESAT, and (c) formation of a multidisciplinary diagnostic team. The training sessions aimed to raise awareness and familiarize trainees with ASD (especially its early signs) and the use of the referral protocol. In total, 39 sessions were delivered, of which 22 were for primary care providers because they are most likely to refer young children at risk for ASD. The remaining 17 sessions were attended by other health professionals (e.g. general practitioners, speech and language therapists). Attendance was compulsory for primary care workers, who were awarded CME (continuing medical education) points. In the program, professionals were required to administer the ESAT (with the assistance of the parents) before they referred children younger than 36 months for assessment of ASD. This 14-item questionnaire focuses on early social communication skills and restricted and repetitive behaviors in children younger than 36 months (Dietz et al., 2006; Swinkels et al., 2006). Children who failed 3 or more items were considered to be at risk and underwent further assessment. For those children who screened negative with the ESAT (failing <3 items), the referring professional had to provide additional information showing that the child was at risk. Within 2 weeks of referral, families were invited to the Karakter Child and Adolescent Psychiatry University Centre. A multidisciplinary team for infant psychiatry, specialized in the early diagnosis of ASD, carried out the diagnostic assessment of all referrals. More information about the early detection program can be obtained from the last author (I.J.O.).

Measures

Age at referral

To identify the long-term effects of the early detection program, the age at referral was compared before, during, and after the program. Data were retrieved from electronic medical records. Since the early detection program focused on children younger than 36 months of age, a differentiation was made between referrals before 3 years of age (0–35 months) and 3 to 6 years of age (36–83 months).

Cognitive functioning

Intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were assessed with age-appropriate measures, most frequently the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995), the Psychoeducational Profile-Revised (Schopler et al., 1990), the Snijders-Oomen non-verbal intelligence test (Tellegen et al., 1998), and the Wechsler tests (Wechsler, 1997, 2002). The level of cognitive functioning was categorized in three groups: < 70, 70–89, and ⩾90.

Data analysis

Binary logistic regression modeling was used to evaluate the long-term effects of the early detection program after it ended while controlling for overall changes in the number of referrals. The effect of diagnosis (ASD, non-ASD), time point (before, during, and after the program), and the interaction diagnosis*time point on the likelihood that children younger than 3 years (versus children aged 3–6 years) were referred was investigated.

Binary logistic regression modeling was also used to investigate the effect of other potential predictors (i.e. cognitive functioning and sex) on the age at referral of children diagnosed with ASD, using IQ (< 70, 70–89, and ⩾90), sex (male, female), and time point as potential predictors. The interaction effects IQ*time point and sex*time point were also included in the model. If the interaction or main effects were non-significant, predictors were dropped from the final model.

Information about the level of cognitive functioning was missing in 8.8% (n = 45) of the ASD cases (cognitive data were unavailable for children with non-ASD diagnoses). Multiple imputation with the expectation maximization algorithm was used to account for the missing data in the group of children with ASD.

Results

The use of multiple imputation only marginally changed outcomes and did not alter conclusions. Below, we present the results with multiple imputation.

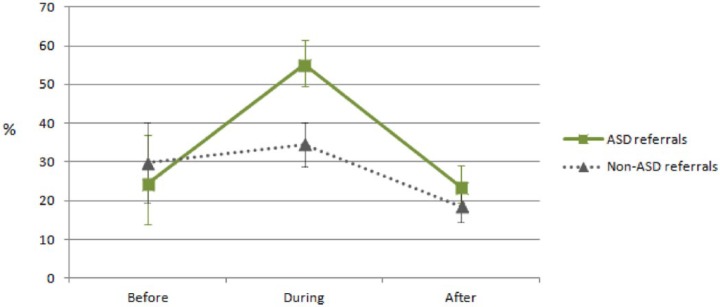

Change in proportion of children referred before 3 years

Figure 1 shows the change in proportion of children referred before 3 years of age by diagnosis and time point. Binary logistic regression analyses revealed that there was a significant interaction effect for diagnosis*time point on the age at referral (χ(2) = 7.90, p = 0.019). The odds of being referred before 3 years for children diagnosed with ASD versus a non-ASD condition was significantly higher during the program than before (3.1, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.2–7.6, p < 0.05) or after (1.7, 95% CI: 1.0–3.0, p < 0.05) the program, but not before versus after the program (1.8, 95% CI: 0.7–4.5, p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Percentage of children referred before 3 years of age by diagnosis and time point with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

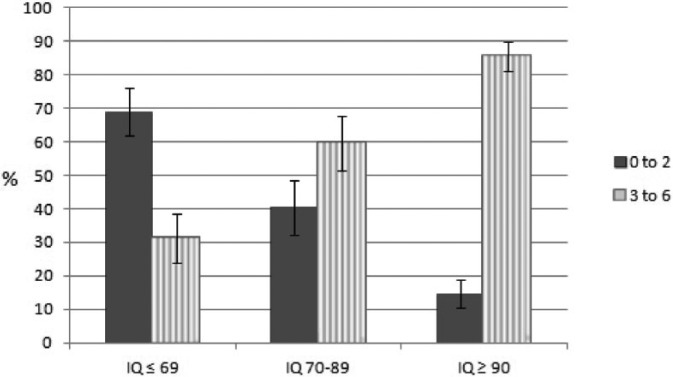

Predictors of age at referral for children with an ASD diagnosis

Regarding ASD participants, there was no significant overall interaction effect IQ*time point (χ(4) = 5.43, p = 0.25), which implied that the effect of cognitive functioning on age at referral was not related to the effect of the program. Nonetheless, the main effect of cognitive functioning on the age at referral was significant (χ(2) = 72.50, p < 0.001). The odds of being referred before 3 years was 2.6 times (95% CI: 1.6–4.2, p < 0.001) and 10.0 times (95% CI: 5.9–16.9, p < 0.001) higher if a child with ASD had an IQ < 70 as compared to an IQ between 70 and 89 and an IQ ⩾ 90, respectively. The odds ratio for being referred was 3.9 times (95% CI: 2.3–6.5, p < 0.001) higher for children with ASD with an IQ between 70 and 89 than for children with ASD with an IQ ⩾ 90. No significant effects of sex were found. Figure 2 shows the percentage of children with ASD referred before 3 years versus between 3 and 6 years by level of cognitive functioning at all three time points.

Figure 2.

Percentage of children with autism spectrum disorder at all time points by age at referral and level of cognitive functioning with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

This is the first quasi-experimental study to investigate the sustainability of the effect of an integrated screening program for the early detection of ASD after the program ended. Results clearly underline the need for continued investment: the odds of being referred before 3 years of age for children with ASD versus non-ASD was higher when the early detection program was implemented than before or after its implementation, but not before versus after the implementation of the program. Thus, although the early detection program led to earlier referral of children with ASD when corrected for other referrals, the effect was not sustained after the program ended. At all times points, children with intellectual disabilities were more likely to be referred before 3 years of age than were children with a higher level of cognitive functioning.

Lack of sustainable effects and how to deal with it

The findings suggest that the early detection program fulfilled its objective to improve the early detection of ASD over the years of active investment, but the effect disappeared after active investment had faded out. This is in line with the study of Holzer et al. (2006), who showed that a decrease in mean age at diagnosis was not sustained 2 years after implementation. In this study, the lack of financial support was the major barrier, as was also noted by Zwaigenbaum et al. (2015b) as one of the key barriers to the early detection of ASD. The lack of financial support ended the intensive collaboration between primary and specialist care (e.g. no prompts were given to the primary care providers), which may have resulted in a lack of awareness among primary care providers. Additionally, no training sessions were provided after the program ended, which meant that experience and knowledge about early detection were lost if staff left. Continuation of the program, with training of personnel, would be expensive. Given that the financing of mental healthcare is generally under pressure, the question is how to develop effective strategies that require minimal financial support but which have a permanent impact.

In order to improve the early detection of ASD, collaboration within and between countries, with the sharing of knowledge, is essential and will help to develop a standardized approach to the detection of ASD. As such, the European network COST Action “Enhancing the Scientific Study of Early Autism” (ESSEA) was initiated with a view to increasing knowledge about the early signs of autism, by combining techniques from cognitive neuroscience with those from clinical sciences, and by reviewing the state of art of early identification (Garcia-Primo et al., 2014) and intervention (McConachie et al., 2015; Salomone et al., 2016) practices in Europe. The COST-ESSEA network inspired Dutch researchers and clinical experts in the field of early autism to form a national interdisciplinary network in 2013. This network promotes collaboration in scientific studies, the exchange of knowledge, and the translation of knowledge into practical tools (e.g. for use in primary care practice). The network operates in close collaboration with primary care providers and the parents of children with ASD as experience experts. As previously suggested by Miller et al. (2011), we strongly believe that intensifying the collaboration between autism experts, primary care providers, and parents will facilitate the timely referral of children at risk for ASD.

Another key element in the early detection of ASD is the availability and accessibility of knowledge for both parents and healthcare professionals. In the Netherlands, a state-of-the-art online platform is currently being developed which will provide parents and professionals with red flag early signs of ASD and information about the diagnosis and relevant services. Also, e-learning and live online learning (LoL) modules are being developed. The e-learning module teaches professionals about the early signs of ASD, whereas the LoL module involves the discussion of specific case studies of the professionals themselves in a virtual online classroom and with the support of an experienced clinician (Oosterling et al., 2016; Van’t Hof et al., 2017). In the United States, similar collections of web-based tools and courses are available (http://www.autismnavigator.com and http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/actearly/), including a specific course about early signs of ASD. These trends imply that e-health technology can have a pivotal role in raising awareness and maintaining the effects of early detection programs without incurring high costs. Research into the effect of these methods is required to evaluate their effectiveness.

The role of cognitive functioning in early detection

Regardless of the time point, children with intellectual disabilities were more likely to be referred for assessment before 3 years of age than were children with a higher level of cognitive functioning. Previous research has shown that children with cognitive impairment (IQ < 70) are younger at the time of ASD diagnosis than higher functioning children (Mazurek et al., 2014; Shattuck et al., 2009). Children with concurrent ASD and cognitive impairment may have more obvious behavioral and developmental challenges, which increase the likelihood of early detection. Vice versa, high-functioning children may be better able to compensate for their difficulties and/or may show more subtle impairments at a preschool age. This is now also acknowledged in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5), which states that “deficits may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). On one hand, given their more subtle symptoms, an early diagnosis is likely to be missed in these children and consequently they will not benefit from early intervention. On the other hand, it may simply not be possible to detect ASD in this group at an early stage, and attempts to do so might result in a high number of false positives. This argues for repeat evaluation in early childhood around 4–6 years of age when potential problems in social relationships with peers start to emerge.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths, including the embedding in a naturalistic context, a large sample size, and the use of a non-ASD group. However, it also had some limitations. To the best of our knowledge, there were no changes in the healthcare system or policy during the period covered by the study, although there may have been unknown changes in clinical practice (e.g. availability of healthcare providers) that influenced referral practices and hence the age at referral. Ideally, long-term effects should be examined in a controlled study including the same regions as in the original study, but we did not receive permission from one of the institutions in the control region to use their data. However, by comparing referrals later diagnosed with ASD with referrals diagnosed with other (non-ASD) conditions, the effect of the early detection program could be examined while controlling for the most important potential confounders. Although our findings provide evidence for the effectiveness of the program, the question remains whether children who were referred before 3 years of age had better outcomes than children referred later. For an ultimate justification of early detection, the long-term effects on child development and quality of life should be investigated. Therefore, future studies should longitudinally follow-up children from the general population who are randomly assigned to undergo (or not) a screening program, regardless of whether they screen positive or negative with regard to the likelihood of ASD. In addition, the effectiveness of early interventions for young children identified by means of an early detection program should be further investigated.

Conclusion and clinical implications

In conclusion, although the program improved the early detection of ASD, its effect was not sustained when the financial support needed to train health professionals ended. These findings highlight the importance of maintaining early detection through continuous investment in active screening and ongoing training of primary care providers. Given the evidence that screening programs can detect autism in an early stage, long-term investment merits a high place on the political agenda. Policymakers and healthcare managers should consider specific strategies to overcome barriers when implementing (and maintaining the effects of) early detection programs. Although labels are needed to refer children to appropriate services, the ultimate goal of early detection is to identify early signs, discuss concerns with families, and guide parents in how to best support their child. Instead of a “wait-and-see” approach, we strongly argue that follow-up services and appropriate interventions will be made available for at-risk children.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, AUT717977_Lay_Abstract for Sustainability of an early detection program for autism spectrum disorder over the course of 8 years by Mirjam KJ Pijl, Jan K Buitelaar, Manon WP de Korte, Nanda NJ Rommelse and Iris J Oosterling in Autism

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank all parents and children who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement number 278948 (TACTICS) and the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement number 115300 (EU-AIMS), resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) companies’ in-kind contribution, and by the European Community’s Horizon 2020 Program (H2020/2014–2020) under grant agreement n° 642996 (BRAINVIEW).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, et al. (1996) Psychological markers in the detection of autism in infancy in a large population. The British Journal of Psychiatry 168: 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brian J, Bryson SE, Smith IM, et al. (2015) Stability and change in autism spectrum disorder diagnosis from age 3 to middle childhood in a high-risk sibling cohort. Autism 20: 888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Haubus C, Dugmore S, et al. (2005) A model of early detection and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in young children. Infants & Young Children 18: 200–211. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels AM, Mandell DS. (2014) Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: a critical review. Autism 18: 583–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz C, Swinkels S, van Daalen E, et al. (2006) Screening for autistic spectrum disorder in children aged 14–15 months. II: population screening with the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire (ESAT). Design and general findings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36: 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Munson J, Rogers SJ, et al. (2015) Long-term outcomes of early intervention in 6-year-old children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 54: 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Primo P, Hellendoorn A, Charman T, et al. (2014) Screening for autism spectrum disorders: state of the art in Europe. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 23: 1005–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer L, Mihailescu R, Rodrigues-Degaeff C, et al. (2006) Community introduction of practice parameters for autistic spectrum disorders: advancing early recognition. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36: 249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman JM, Ventola PE, Pandey J, et al. (2008) Diagnostic stability in very young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 38: 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Nefdt N, Koegel RL, et al. (2006) A screening, training, and education program: first STEP. In: Koegel RL, Koegel LK. (eds) Pivotal Response Treatments for Autism: Communication, Social and Academic Development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing, pp; 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, et al. (2006) Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry 63: 694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConachie H, Fletcher-Watson S. and Working Group CAESSEA (2015) Building capacity for rigorous controlled trials in autism: the importance of measuring treatment adherence. Child: Care, Health and Development 41: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Brown R, Curran A, et al. (2017) ECHO autism: a new model for training primary care providers in best-practice care for children with autism. Clinical Pediatrics 56: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Handen BL, Wodka EL, et al. (2014) Age at first autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: the role of birth cohort, demographic factors, and clinical features. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 35: 561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JS, Gabrielsen T, Villalobos M, et al. (2011) The each child study: systematic screening for autism spectrum disorders in a pediatric setting. Pediatrics 127: 866–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen E. (1995) Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterling I, Dietz C, Vlamings C, et al. (2016) Met vereende kracht op weg naar vroegere herkenning van autisme in heel Nederland. In: Nationaal Autisme Congres 2016 (NAC), Rotterdam, 11 March. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterling IJ, Wensing M, Swinkels SH, et al. (2010) Advancing early detection of autism spectrum disorder by applying an integrated two-stage screening approach. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 51: 250–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Landa RJ, et al. (2015) Diagnostic stability in young children at risk for autism spectrum disorder: a baby siblings research consortium study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 56: 988–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner M, Rayar M, Bashir N, et al. (2015) Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing pre-diagnosis autism spectrum disorder (ASD)-targeted intervention with Ontario’s Autism Inter-vention Program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 45: 2833–2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters-Scheffer N, Didden R, Korzilius H, et al. (2012) Cost comparison of early intensive behavioral intervention and treatment as usual for children with autism spectrum disorder in The Netherlands. Research in Developmental Disabilities 33: 1763–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Le Couteur A, Leadbitter K, et al. (2016) Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 375: 2152–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone E, Beranova S, Bonnet-Brilhault F, et al. (2016) Use of early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder across Europe. Autism 20: 233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Bashford A, et al. (1990) The Psychoeducational Profile Revised (PEP-R). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Durkin M, Maenner M, et al. (2009) Timing of identification among children with an autism spectrum disorder: findings from a population-based surveillance study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48: 474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson AR, Warren ZE, Stone WL, et al. (2014) The diagnosis of autism in community pediatric settings: does advanced training facilitate practice change? Autism 18: 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels SH, Dietz C, van Daalen E, et al. (2006) Screening for autistic spectrum in children aged 14 to 15 months. I: the development of the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire (ESAT). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 36: 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen PJ, Winkel M, Wijnberg-Williams BJ, et al. (1998) Snijders-oomen Niet-verbale Intelligentietest SON-R 2.5-7. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Van Daalen E, Kemner C, Dietz C, et al. (2009) Inter-rater reliability and stability of diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder in children identified through screening at a very young age. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 18: 663–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van’t Hof M, Bailley JT, Hoek HW, et al. (2017) Detection of autism spectrum disorders in children aged 4–6 years by municipal maternal and child health physicians: an educational intervention study. In: International meeting for autism research (IMFAR), San Francisco, CA, 10–13 May. [Google Scholar]

- Webb SJ, Jones EJH, Kelly J, et al. (2014) The motivation for very early intervention for infants at high risk for autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 16: 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1997) Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (2002) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-III–NL. Amsterdam: Harcourt Test Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Choueiri R, et al. (2015. a) Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics 136(Suppl. 1): S60–S81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Fein D, et al. (2015. b) Early screening of autism spectrum disorder: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics 136(Suppl. 1): S41–S59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, AUT717977_Lay_Abstract for Sustainability of an early detection program for autism spectrum disorder over the course of 8 years by Mirjam KJ Pijl, Jan K Buitelaar, Manon WP de Korte, Nanda NJ Rommelse and Iris J Oosterling in Autism