Abstract

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma is defined as a nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) that contains at least 10% sarcomatoid components. We report a case of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma of which only the sarcomatoid component metastasized to the small bowel and adenocarcinoma was identified on percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB). We suggest that if an NSCLC is diagnosed by PTNB and a sarcoma is found at another site, or vice versa, pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma with a single metastasis should be considered as a differential diagnosis to establish the best effective treatment plan.

Keywords: Metastasis, pleomorphic carcinoma, small bowel

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma is a rare lung cancer with low incidence, ranging from 0.1%–0.4% of all lung cancers.[1] It is defined as a poorly differentiated nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) containing at least 10% sarcomatoid components of spindle or giant cells, or a carcinoma comprised solely of sarcomatoid components.[2]

The preoperative diagnosis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma is difficult due to tumor heterogeneity.[3] In addition, single pathologic component metastasis from pleomorphic carcinoma can cause diagnostic confusion before surgery. However, reports related to single pathologic component metastasis is not well known.[4]

In this study, we report a pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma mimicking pulmonary adenocarcinoma and small bowel sarcoma due to single pathologic component metastasis.

Case Report

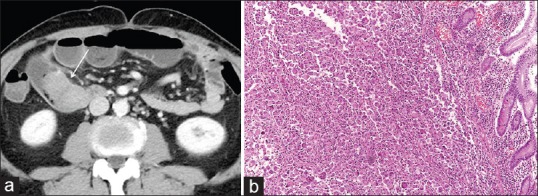

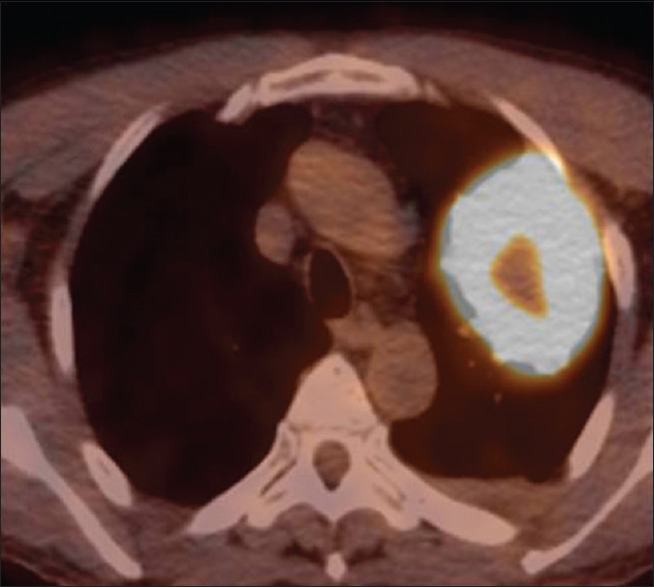

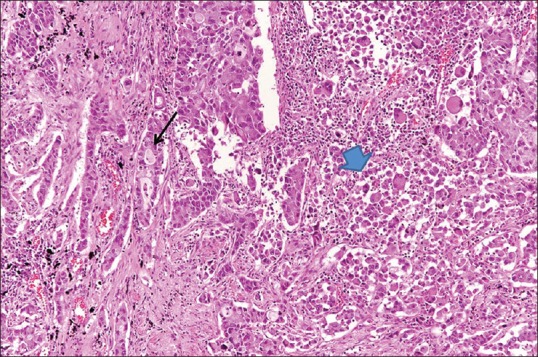

A 63-year-old male visited the emergency room with abdominal pain. A simple abdominal radiograph showed multiple air-fluid levels, suggesting small bowel obstruction, and contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. An approximately 6-cm enhancing mass that was obstructing the small bowel ileum was identified on abdominal CT [Figure 1a] Emergency small bowel resection was performed, and the mass was diagnosed as a giant-cell carcinoma on pathologic examination [Figure 1b] At the time of admission, contrast-enhanced chest CT was performed to evaluate the lung mass incidentally found on chest radiography. Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed a 7.3-cm lobulated mass containing central necrotic changes in the left upper lobe [Figure 2] No enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were found. Because of the central necrotic areas of the lung mass, a percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB) was performed to target the peripheral portion of the mass. The mass was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma on PTNB. The mass showed high 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake (maximum standardized uptake value of 17) on an FDG positron emission tomography CT scan [Figure 3] Since synchronous lung adenocarcinoma and small bowel sarcoma cannot be excluded, the patient underwent lobectomy of the left upper lobe. The surgical pathological specimen showed that it was composed of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma at the periphery of the mass and giant-cell carcinoma with necrosis in the center of the mass [Figure 4]. The dissected thoracic lymph nodes were all negative for metastasis. Immunohistochemically, the mass stained positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, thyroid transcription factor, napsin A, and Vimentin with negative of P40. Molecular test was negative for epidermal growth factor receptor. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with primary lung cancer – pleomorphic carcinoma with a single metastasis to the small bowel (T3N0M1b). He was treated with four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of carboplatin and paclitaxel and has achieved 12 months of recurrence-free survival.

Figure 1.

(a) Abdominal computed tomography shows a 6-cm enhancing mass in the small bowel that is obstructing the entire lumen (arrow). There is luminal dilatation of the distal loop of the small bowel. (b) High-power photomicrograph (original magnification, ×100; H and E stain) of the specimen obtained by small bowel resection shows a multinucleated giant-cell carcinoma. H and E: hematoxylin and eosin

Figure 2.

There is a 7.3-cm lobulated mass with central low attenuation, suggesting a necrotic change in the left upper lobe. No enlarged mediastinal lymph node was found on chest computed tomography

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography–computed tomography shows a large mass with high uptake measuring maximum SUV of 17 in the left upper lung lobe. The central area of the mass reveals a relatively low uptake, which corresponds to low attenuation of the chest computed tomography

Figure 4.

High-power photomicrograph (original magnification, ×200; H and E stain) of a surgical specimen obtained at lobectomy of the lung mass shows the adenocarcinoma component on the left (arrow) and giant-cell carcinoma on the right, central direction (arrowhead) being sharply separated from each other. H and E: hematoxylin and eosin

Discussion

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma is a rare type of lung cancer that comprises 0.1%–0.4% of malignant tumors of the lung.[1] According to the criteria of the World Health Organization classification, pleomorphic carcinoma is defined as a poorly differentiated NSCLC, such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or large cell carcinoma that contains at least 10% sarcomatoid components of spindle cells and/or giant cells, or a carcinoma comprised entirely of spindle and giant cells.[2]

Pleomorphic carcinoma is difficult to be diagnosed before surgery with biopsies or cytology.[3,5] Oikawa et al. reported that when comparing preoperative diagnosis by transbronchial lung biopsy with surgical resection in 126 cases of lung cancer, five were diagnosed as pleomorphic carcinoma among 19 noncorresponding cases. This may be explained by the great tumor heterogeneity of pleomorphic carcinoma.[3] In our case, since PTNB was targeted to the peripheral area, only adenocarcinoma located in a peripheral portion of the mass on the pathologic specimen was identified with PTNB.

Our case of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma exhibited a single metastasis to the small bowel. Interestingly, when the surgical pathology specimen obtained by small bowel resection was analyzed, only a sarcoma component was observed without any adenocarcinoma. A previous study reported that only one pathologic component, such as an epithelial or mesenchymal component, can metastasize to another organ.[4] In such a case, a pathologic discrepancy between them may occur, further confusing the clinician, since it is difficult to determine whether the case may be that of a double primary cancer or a stage IV lung cancer with a metastasis.

Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma has a poorer clinical outcome than other conventional NSCLCs.[6] As pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma responds poorly to chemotherapy,[7] complete resection of both primary and metastatic masses in patients without lymph node metastases is suggested as another treatment option.[8,9,10]

Consequently, pathologic discrepancy between primary and metastatic masses can occur due to single component metastasis and the tumor heterogeneity of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. If an NSCLC is diagnosed by PTNB and a sarcoma is found at another site, or vice versa, pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma may be considered as a differential diagnosis, and this may help clinicians in deciding on further treatment plans.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chang YL, Lee YC, Shih JY, Wu CT. Pulmonary pleomorphic (spindle) cell carcinoma: Peculiar clinicopathologic manifestations different from ordinary non-small cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2001;34:91–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beasley MB, Brambilla E, Travis WD. The 2004 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors. Semin Roentgenol. 2005;40:90–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oikawa T, Ohira T, Matsubayashi J, Konaka C, Ikeda N. Factors influencing the diagnostic accuracy of identifying the histologic type of non – small-lung cancer with small samples. Clin Lung Cancer. 2015;16:374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, De Pas T, Galetta D, Veronesi G, Spaggiari L, et al. Review article: Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas: A practical overview. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:103–20. doi: 10.1177/1066896908330049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, Yatabe Y, Austin JH, Beasley MB, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: Impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1243–60. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhao L, Jing H, Sang S, Du J, et al. Pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7465. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae HM, Min HS, Lee SH, Kim DW, Chung DH, Lee JS, et al. Palliative chemotherapy for pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2007;58:112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miura N, Mori R, Takenaka T, Yamazaki K, Momosaki S, Takeo S, et al. Stage IV pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung without recurrence for 6 years: A case report. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:36. doi: 10.1186/s40792-017-0310-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamanashi K, Marumo S, Miura K, Kawashima M. Long-term survival in a case of pleomorphic carcinoma with a brain metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7:799–803. doi: 10.1159/000368186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aokage K, Yoshida J, Ishii G, Takahashi S, Sugito M, Nishimura M, et al. Long-term survival in two cases of resected gastric metastasis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:796–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817c925c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]