Abstract

Objective

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide. We conducted network meta-regression within a Bayesian framework to compare and rank different treatment strategies for HCC through direct and indirect evidence from international studies.

Methods and analyses

We pooled the OR for 1-year, 3-year and 5-year overall survival, based on lesions of size ˂ 3 cm, 3–5 cm and ≤5 cm, using five therapeutic options including resection (RES), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation (MWA), transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus RFA (TR) and percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI).

Results

We identified 74 studies, including 26 944 patients. After adjustment for study design, and in the full sample of studies, the treatments were ranked in order of greatest to least benefit as follows for 5 year survival: (1) RES, (2) TR, (3) RFA, (4) MWA and (5) PEI. The ranks were similar for 1- and 3-year survival, with RES and TR being the highest ranking treatments. In both smaller (<3 cm) and larger tumours (3–5 cm), RES and TR were also the two highest ranking treatments. There was little evidence of inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence.

Conclusion

The comparison of different treatment strategies for HCC indicated that RES is associated with longer survival. However, many of the between-treatment comparisons were not statistically significant and, for now, selection of strategies for treatment will depend on patient and disease characteristics. Additionally, much of the evidence was provided by non-randomised studies and knowledge gaps still exist. More head-to-head comparisons between both RES and TR, or other approaches, will be necessary to confirm these findings.

Keywords: resection, radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, percutaneous ethanol injection, hepatocellular carcinoma

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a network meta-regression within a Bayesian framework to compare and rank different treatment strategies for HCC through direct and indirect evidence from international studies.

Strong and reliable methodological and statistical procedures were applied.

The individual or tumour characteristics within HCC articles would be a source of heterogeneity.

A major limitation is in the inclusion of non-randomised studies, in which selection bias is likely to confound observations. Selection of treatment is likely to be based on individual or tumour characteristics, and thus these factors will bias and confound observations of survival.

Other studies did not report the primary outcome of interest (5-year survival) and this was a particular limitation among randomised studies.

Introduction

Cancer was the second leading cause of death in 2013, behind cardiovascular disease, and in 2013 more than 8 million people died from cancer globally.1–3 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer death, with 5-year overall survival rates under 12%.4 5

Hepatic resection (RES) was the traditional choice for patients with HCC, without cirrhosis and with good remaining liver function.6 Despite nearly 70% 5-year survival, recurrence rates after surgery were high.7 Repeated hepatectomies to lengthen survival were not often appropriate owing to multiple-site tumour recurrence or patient background of liver cirrhosis.8 9 Many locoregional therapies have been developed including ablative treatments such as percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation (MWA) and transarterial therapies such as transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation (TACE) or transarterial chemotherapy infusion (TACI). Locoregional therapies were minimally invasive and therefore are cheaper and faster to recover, as compared to resection. Such approaches may be appropriate for patients with unresectable, small or multiple carcinomas or those with severe cirrhosis. However, there may be a greater risk of recurrence because of incomplete destruction of cancer cells at the treatment margin, as seen with RFA.10

The selection of treatment strategy was determined by liver function, tumour stage and patient performance status,7 but much uncertainty still remains surrounding the comparative efficacy of different treatment approaches. A recent review of international guidelines for HCC found similarities but also some discrepancy in treatment allocation recommendations because of regional classification differences, secondary to a lack of solid or high-level evidence.11 A recent review of therapies also revealed that there was no consensus on whether surgery or ablation was better for small tumours.7 Some discrepancy in prevalence and treatment outcomes may be still in different regions because of local biology, available resources or expertise and access to care.11 However, if we ever hope to achieve standardised and evidence-based therapy for HCC, the unanswered question surrounding relative treatment efficacy of RES compared with ablative locoregional therapies should be resolved.

Traditional meta-analysis is limited by existing head-to-head treatment comparisons within included studies. It is therefore not possible to gauge the relative benefit of the two treatments that have never been directly compared in studies. Real-life treatment decisions are hindered by gaps in existing evidence, but network meta-analysis enables integration of direct and indirect comparisons to provide estimates for relative comparisons across many treatments.12 Recent published network meta-analysis focused on advanced HCC by TACE alone or combined treatments,13 14 as well as antineoplastic drugs (sorafenib, erlotinib, linifanib, sunitinib and brivanib),15 and early- or very early-stage HCC via surgery or thermal ablation.16 However, in this study, we included the latest literature, and focused on the comparison of interventional and surgical treatments, including RES, RFA, MWA and TACE plus RFA (TR), PEI using subgroup analysis of tumour size (smaller: <3 cm; larger: 3–5 cm) and study design (cohort or randomised clinical trial (RCT)). In order to investigate comparative effectiveness among RES and common locoregional ablative therapies, we performed a strong and reliable Bayesian network meta-analysis.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review and report findings in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Network Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-NMA)17 (online supplementary text S1). The following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus, up to May 2018, using these keywords: resection, surgery, hepatectomy, radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolisation, microwave thermal ablation, ethanol injection, liver, cancer and tumour (online supplementary text S2). No language restrictions were used. Bibliographies from other relevant review articles were cross-examined for potential missed studies. Disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer. Citations were downloaded into reference management software and duplicate citations were electronically or manually removed.

bmjopen-2017-021269supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

We systematically included the studies using the following criteria: (1) original data from prospective or retrospective cohort studies and RCTs in humans; (2) reporting at least two treatments, including resection or any local ablative therapy (RES, RFA, MWA, PEI or TACE+RFA (TR)); (3) mean lesion size ≤5 cm and (4) evaluating overall survival rate not less than 1 year after first or recurrent treatments. Conference abstracts and case reports were excluded, as were older publications from studies with multiple publications.

Patients and public involvement

The patients or public were not involved in the study.

Data extraction and study quality

Two investigators independently extracted and cross-checked the data from the eligible studies: author, year, study design, country, disease type, inclusion criteria, treatment style, study size, gender, age, tumour size, follow-up duration, treatment complications and survival outcomes. If in disagreement, a third reviewer was asked to adjudicate. The level of evidence was appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidance,18 which was classified into four levels: high, moderate, low and very low. The quality score was downgraded according to five domains, including the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias while scores were upgraded according to large effect, appropriate control for plausible confounding and dose–response gradient.

Data analysis

Network meta-analysis was used if a ring or open evidence loop was available to know the number of arms and the sample size of each intervention. When possible, pair-wise direct head-to-head comparisons were conducted to calculate the OR of 1-, 3- and 5-year survival and their 95% CI. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using the tau-squared statistic (τ).2 19 A node-splitting analysis was applied to check the consistency between direct evidence (existing real reported comparisons) and indirect evidence (estimated treatment comparisons) for their agreement on a specific node.20 Bayesian network meta-analysis with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), through a consistency model, was utilised to estimate the pooled ORs and its 95% credible interval (CrI) for direct and indirect comparisons.16 The inconsistency model was used to check for heterogeneity due to chance imbalance in the distribution of effect modifiers. Consistency in every closed loop was checked by the loop-specific approach in order to estimate whether treatment survival effects were disturbed by variance in the distribution of potential confounding factors among the studies. In order to compare and rank survival rates of different treatments, we examined all studies first and then separately assessed smaller (<3 cm) and larger (3–5 cm) tumours. Random-effect meta-regression models were used, with and without adjustment for study design (cohort or RCT) and subgroup analyses were also conducted for RCTs in order to examine treatment effectiveness. We appraised the ranking probabilities for all therapies for each intervention and the treatment hierarchy was ordered by the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA).21 Sensitivity analysis was conducted to remove each study, in turn, and estimate the treatment effect in the remaining studies. Funnel plots were utilised to check the possible presence of publication bias or small-study bias.22 In this study, we used Bayesian MCMC simulations by WinBUGS 1.4 and graphically presented the results using Stata V.13.

Results

Study characteristics

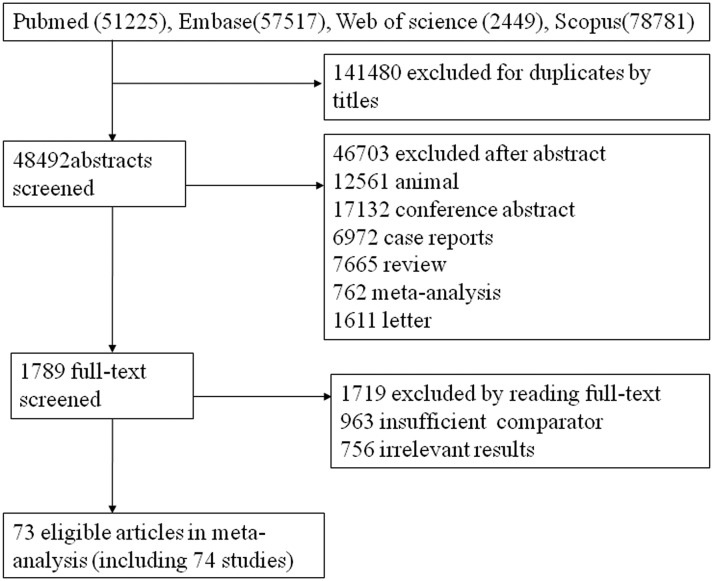

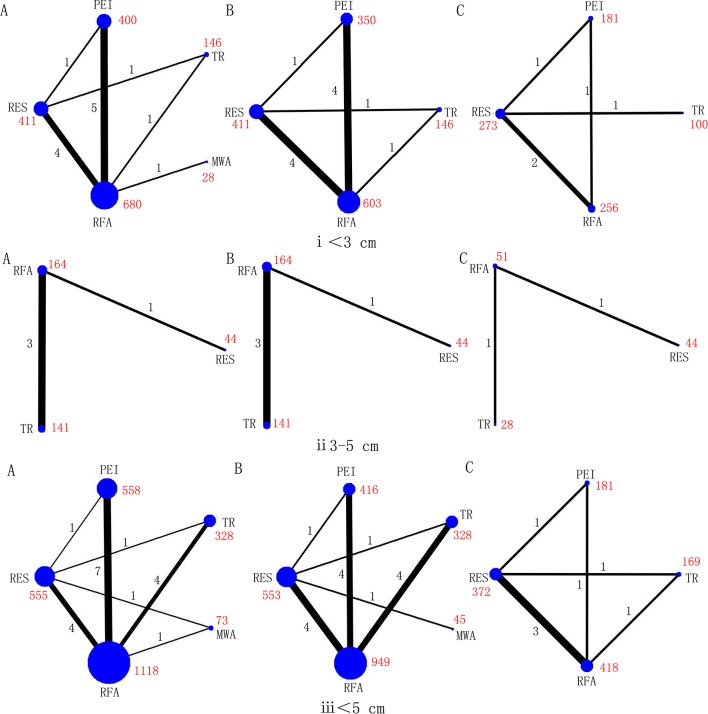

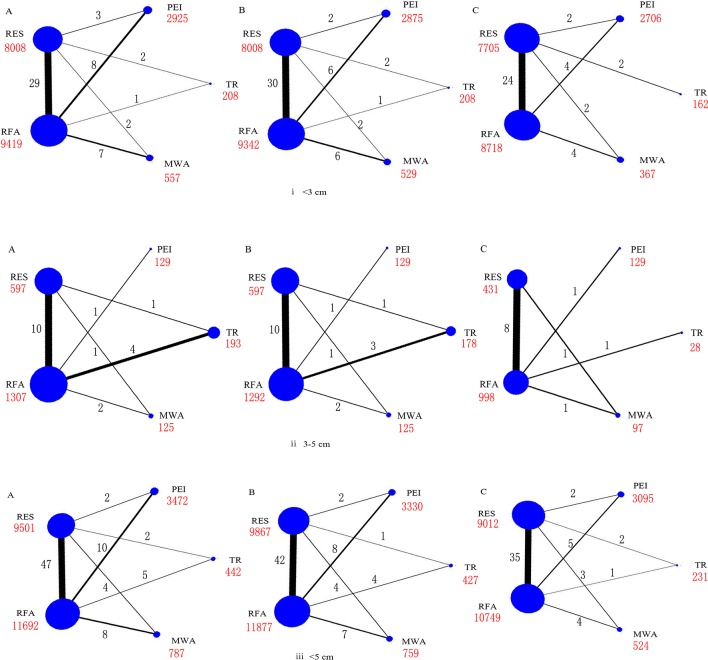

After screening, 74 relevant studies in 73 articles were identified, of which 20 were RCTs and 54 were cohort studies.23–96 We excluded 136 504 duplicate or non-relevant citations (figure 1). The summary characteristics of these studies are shown in online supplementary table S1. Overall, 32 345 patients of mean age from 46 to 73.5 years, with approximately 29 236 tumours, were assigned to receive RES, RFA, MWA, TR and PEI, and the mean follow-up ranged from 1.5 to 5.7 years. In addition, the number of connected studies to the lines (black) and sample size of each treatment (red) were shown in figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search.

Figure 2.

Networks of treatment comparisons for 1 year (A), 3 year (B), and 5 year (C) survival rates in RCTs. Circle size is proportional to the number of included patients and line width indicates the number of studies comparing the connected treatments. The number in red indicates the sample size and the number in black indicates the number of studies. (i) Lesions <3 cm. (ii) Lesions 3–5 cm. (iii) Lesions≤5 cm.

Figure 3.

Networks of treatment comparisons for 1 year (A), 3-year (B), and 5-year (C) survival rates in all the studies. Circle size is proportional to the number of included patients and line width indicates the number of studies comparing the connected treatments. The number in red indicates the sample size and the number in black indicates the number of studies. (i) Lesions <3 cm. (ii) Lesions 3–5 cm. (iii) Lesions≤5 cm.

Network meta-analysis results

Ten possible treatment comparisons among the five interventions were examined in the included studies. Comparable survival estimates were made for each treatment (per 1000 patients) and the survival OR among each of the treatment comparisons, according to follow-up duration, are presented in online supplementary table S2, along with estimation of the quality of evidence using GRADE criteria.

Across the range of treatment comparisons and follow-up durations, evidence was graded between low and high quality. Evidence was often graded as low quality owing to publication bias and graded as high quality owing to a larger number of participants in direct comparisons.

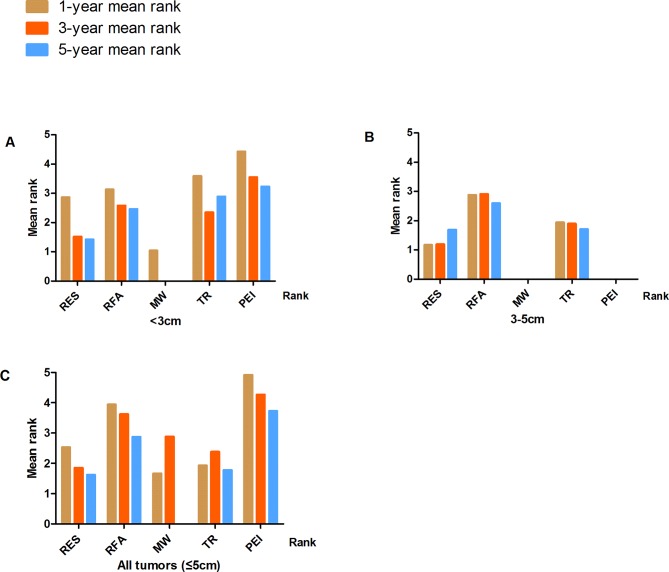

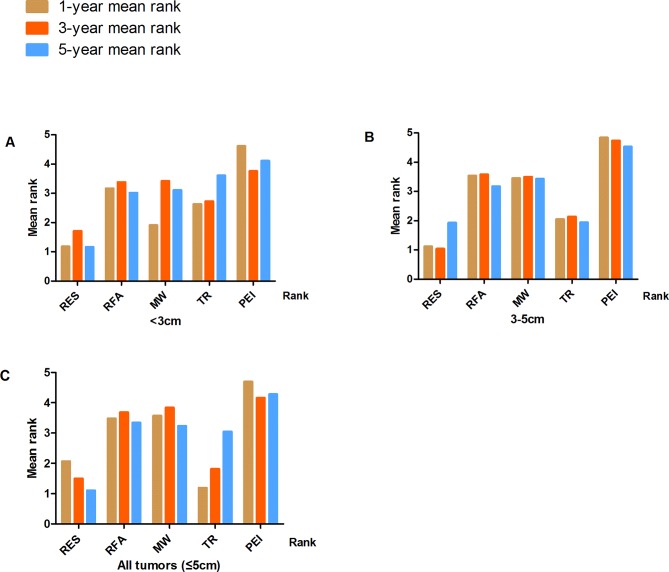

Survival probabilities (estimated using Meanrank) and ranks for the five treatments in patients with tumours <3 cm, 3–5 cm or ≤5 cm (with and without adjustment for study design) are graphically displayed in figures 2–5, and numerical details are given in online supplementary tables S3–S4. RES was consistently associated with greater survival (rank 1) compared with MWA, RFA, TR and PEI for the 5-year survival estimates. The ranks were similar for 1- and 3-year survival with RES or TR being ranked as 1 or 2 in most analyses. After adjustment for study design, and in the full sample of available studies (n=74), the treatments were ranked as follows for 5-year survival: (1) RES, (2) TR, (3) RFA, (4) MWA and (5) PEI (online supplementary table S4).

Figure 4.

Treatment ranks for 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates, according to lesion size in RCTs: (A) Lesions <3 cm. (B) Lesions 3–5 cm. (C) Lesions≤5 cm (full sample).

Figure 5.

Treatment ranks for 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates, according to lesion size in all studies. (A) Lesions <3 cm. (B) Lesions 3–5 cm. (C) Lesions ≤5 cm (full sample).

Efficacy comparisons from network meta-regression for all treatments are summarised in tables 1 and 2, according to follow-up duration and initial tumour size. Compared with RES, the 5-year survival in all studies (trials and observational studies) for all tumours ≤5 cm, was 0.45 (95%CrI 0.23 to 0.82) for PEI, 0.59 (95%CrI 0.25 to 1.20) for TR, 0.55 (95%CrI 0.25 to 1.05) for MWA and 0.52 (95%CrI 0.29 to 0.88) for RFA (table 2). When examining the comparisons across all treatments, the only significant difference for tumours<3 cm was for 5-year survival, and a significantly worse survival was observed for PEI compared with RES 0.43 (95%CrI 0.17 to 0.89). For tumours between 3 and 5 cm, no significant differences were observed at 5-year survival, but significantly worse 3-year survival was observed with PEI, MWA and RFA compared with RES (table 2). Despite smaller number of studies in analyses of only RCTs, the pairwise comparisons showed similar results. However, all relative rankings should be interpreted with caution because most network meta-regression comparisons did not suggest a statistically significant difference between treatments. Detailed results of each comparison for survival rates were shown in online supplementary tables S5–S10.

Table 1.

ORs (95% credible interval) according to network meta-analyses for the survival for all pairwise comparisons in randomised controlled trials

| <3 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 1.17 (0.11 to 4.66) | TR | |||

| 0.08 (0 to 0.38) | 0.15 (0 to 0.80) | MWA | ||

| 0.67 (0.28 to 1.35) | 1.25 (0.16 to 4.64) | 173.30 (1.90 to 537.40) | RFA | |

| 0.64 (0.18 to 1.61) | 1.08 (0.15 to 3.78) | 152.70 (1.44 to 505.80) | 0.97 (0.42 to 1.98) | RES |

| <3 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 1.02 (0.14 to 3.56) | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| 0.79 (0.45 to 1.39) | 1.54 (0.25 to 13.43) | NA | RFA | |

| 0.58 (0.29 to 1.16) | 1.17 (0.16 to 4.17) | NA | 0.75 (0.41 to 1.31) | RES |

| <3 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 3.93 (0.03 to 19.61) | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| 0.94 (0.08 to 3.97) | 2.87 (0.04 to 13.43) | NA | RFA | |

| 0.50 (0.04 to 2.04) | 0.84 (0.03 to 4.18) | NA | 0.72 (0.10 to 2.47) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| NA | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| NA | 3.40 (0.64 to 11.93) | NA | RFA | |

| NA | 1.00 (0 to 5.00) | NA | 0.25 (0 to 1.47) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| NA | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| NA | 3.98 (0.71 to 15.22) | NA | RFA | |

| NA | 1.14 (0 to 6.20) | NA | 0.24 (0 to 1.25) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| NA | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| NA | 7.64 (0.14 to 42.49) | NA | RFA | |

| NA | 12.87 (0.02 to 44.43) | NA | 1.05 (0.03 to 5.33) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.29 (0.09 to 0.73) | TR | |||

| 0.27 (0.05 to 0.84) | 1.09 (0.16 to 3.50) | MWA | ||

| 0.65 (0.33 to 1.13) | 2.69 (1.02 to 6.04) | 3.84 (0.81 to 11.60) | RFA | |

| 0.37 (0.13 to 0.82) | 1.50 (0.48 to 3.67) | 2.01 (0.47 to 5.70) | 0.57 (0.27 to 1.08) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.64 (0.19 to 1.67) | TR | |||

| 1.05 (0.12 to 4.56) | 1.86 (0.21 to 7.59) | MWA | ||

| 0.86 (0.39 to 1.79) | 1.56 (0.66 to 3.25) | 1.77 (0.22 to 6.24) | RFA | |

| 0.55 (0.19 to 1.44) | 0.98 (0.35 to 2.41) | 1.00 (0.16 to 3.30) | 0.65 (0.31 to 1.29) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.53 (0.06 to 1.90) | TR | |||

| NA | NA | MWA | ||

| 0.74 (0.16 to 2.00) | 2.29 (0.41 to 7.61) | NA | RFA | |

| 0.41 (0.11 to 1.02) | 1.35 (0.23 to 4.69) | NA | 0.66 (0.20 to 1.62) | RES |

The reference treatment (1.00) for all comparisons is listed to the right hand side.

MWA, microwave ablation; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; RES, resection; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TR, transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation and radiofrequency ablation.

Table 2.

ORs (95% credible interval) according to network meta-analyses for the survival for all pairwise comparisons in all studies

| <3 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.69 (0.14 to 2.13) | TR | |||

| 0.49 (0.18 to 1.10) | 1.08 (0.21 to 7.87) | MWA | ||

| 0.68 (0.38 to 1.09) | 1.48 (0.34 to 4.23) | 1.59 (0.69 to 3.17) | RFA | |

| 0.63 (0.22 to 1.44) | 1.30 (0.28 to 3.88) | 1.49 (0.44 to 3.85) | 0.94 (0.39 to 1.91) | RES |

| <3 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.90 (0.29 to 2.17) | TR | |||

| 1.01 (0.47 to 1.95) | 1.38 (0.42 to 3.40) | MWA | ||

| 0.96 (0.59 to 1.50) | 1.31 (0.47 to 2.92) | 1.02 (0.57 to 1.70) | RFA | |

| 0.68 (0.30 to 1.39) | 0.90 (0.31 to 2.10) | 0.73 (0.30 to 1.55) | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.30) | RES |

| <3 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 1.07 (0.31 to 2.72) | TR | |||

| 0.86 (0.39 to 1.65) | 1.03 (0.28 to 2.73) | MWA | ||

| 0.82 (0.48 to 1.29) | 0.99 (0.32 to 2.39) | 1.04 (0.50 to 1.77) | RFA | |

| 0.43 (0.17 to 0.89) | 0.49 (0.16 to 0.18) | 0.55 (0.19 to 1.25) | 0.54 (0.24 to 1.05) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.20 (0.05 to 0.54) | TR | |||

| 0.55 (0.09 to 1.76) | 3.39 (0.58 to 10.44) | MWA | ||

| 0.49 (0.18 to 1.12) | 2.99 (1.14 to 6.58) | 1.29 (0.32 to 3.60) | RFA | |

| 0.06 (0 to 0.31) | 0.36 (0.01 to 2.08) | 0.15 (0 to 1.00) | 0.12 (0 to 0.63) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.28 (0.04 to 0.96) | TR | |||

| 0.61 (0.08 to 2.26) | 2.62 (0.61 to 7.90) | MWA | ||

| 0.55 (0.12 to 1.69) | 2.38 (0.93 to 5.38) | 1.15 (0.39 to 2.65) | RFA | |

| 0.06 (0 to 0.28) | 0.26 (0.01 to 1.10) | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.53) | 0.11 (0.01 to 0.40) | RES |

| 3 to 5 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 5.77 (0.01 to 2.84) | TR | |||

| 4.15 (0.04 to 5.18) | 11.97 (0.19 to 46.76) | MWA | ||

| 0.86 (0.06 to 2.68) | 6.16 (0.27 to 25.58) | 1.26 (0.19 to 4.04) | RFA | |

| 3.02 (0.01 to 2.40) | 14.31 (0.04 to 21.06) | 1.24 (0.02 to 4.46) | 0.69 (0.04 to 3.16) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 1-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.34 (0.11 to 0.63) | TR | |||

| 0.81 (0.38 to 1.51) | 2.69 (0.99 to 6.00) | MWA | ||

| 0.77 (0.51 to 1.10) | 2.55 (1.20 to 4.85) | 1.04 (0.55 to 1.76) | RFA | |

| 0.52 (0.24 to 0.96) | 1.72 (0.66 to 3.70) | 0.70 (0.29 to 1.39) | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.17) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 3-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.64 (0.32 to 1.16) | TR | |||

| 0.98 (0.55 to 1.65) | 1.65 (0.80 to 3.03) | MWA | ||

| 0.94 (0.64 to 1.34) | 1.57 (0.89 to 2.57) | 0.99 (0.64 to 1.47) | RFA | |

| 0.59 (0.30 to 1.04) | 0.97 (0.48 to 1.79) | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.09) | 0.63 (0.37 to 1.01) | RES |

| ≤5 cm for 5-year survival | ||||

| PEI | ||||

| 0.84 (0.35 to 1.74) | TR | |||

| 0.87 (0.46 to 1.51) | 1.16 (0.46 to 2.46) | MWA | ||

| 0.87 (0.57 to 1.26) | 1.16 (0.54 to 2.21) | 1.06 (0.64 to 1.61) | RFA | |

| 0.45 (0.23 to 0.82) | 0.59 (0.25 to 1.20) | 0.55 (0.25 to 1.05) | 0.52 (0.29 to 0.88) | RES |

The reference treatment (1.00) for all comparisons is listed to the right hand side.

MWA, microwave ablation; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; RES, resection; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TR, transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation and radiofrequency ablation.

Loop-specific methods detected no inconsistency between the pairwise and network meta-analysis for most closed loops in the network (online supplementary figure S1). However, inconsistency was observed between direct and indirect comparisons for the following loops: lesions<3 cm: RES-RFA-TR, PEI-RES-RFA, MWA-RES-RFA; lesions 3–5 cm: MWA-RES-RFA, RES-RFA-TR; and lesions≤5 cm: RES-RFA-TR). In addition, tests for inconsistency were carried out (online supplementary tables S11–S13), which indicated a close relationship of between-trial heterogeneity and inconsistency between ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ evidence.

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

No significant change was observed when any one study was deleted. Funnel plots indicated that the included studies in each group were distributed symmetrically around the vertical line (x=0), suggesting that no obvious evidence of publication bias or small-sample effect existed in this network (online supplementary figure S2).

Discussion

There were many techniques for attaining a large ablated zone and complete necrosis of HCC and this comprehensive review addressed two of the more common treatments, namely resection and ablation. In this network meta-analysis, of the five examined therapies, the pooled data showed RES ranked best in full sample analysis with or without adjustment for study design. In both smaller (<3 cm) and larger tumours (3–5 cm), RES remained the highest ranking treatment. However, most of the individual treatment comparisons were not statistically significant and thus, RES may not be superior to all other therapies. Our evidence indicated locoregional therapies and particularly RES or TR (TACE+RFA) were associated with longer survival.

Our observation of better survival outcomes with TR may be through the advantage of dual mechanisms. With TR, TACE-induced hypoxic injury on cancer cells through occlusion of blood vessels and was followed by local ablation. This combination therapy may result in a larger ablated zone,97 reducing the possibility of micrometastasis and recurrence, and thus, resulting in better survival outcomes than RFA alone.

While being more invasive, and despite risk of complications, RES was associated with better survival outcomes after 1 year, 3 years and 5 years. This may be due to removal of larger sections of liver than can be targeted with locoregional therapies, thus removing a larger area of potentially cancerous cells. Additionally, rat models indicated that the liver has the potential to quickly restore its original size after partial hepatectomy. This may be mediated via interactions of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α, interleukin (IL)−6, and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ).98 However, evidence from rat models and human studies indicated that resection success was associated with resection size and regeneration was stunted with larger resections.99–101 The safe limit for remnant liver volume in normal liver was approximately 30% of total liver volume, but this was estimated to rise to 40%–50% in those with liver disease.99 102 Liver resection was recognised as the most efficient treatment for HCC but was only applicable for less than 30% of all patients. However, developments in preoperative imaging techniques, laparoscopic surgery and newly developing combinations with chemotherapy may extend its application to more advanced tumours.102 Furthermore, the consistent associations observed with all studies and only in RCTs indicated that patient selection bias in the observational studies does not wholly explain the better survival outcomes with RES.

Overall, we found PEI was associated with shorter survival than the other four therapies, a finding which is supported in previous studies.24 33 One study reported RFA was superior to PEI in achieving short- and long-term survival outcomes, although PEI and RFA showed similar 5-year survival in lesions<3 cm.55 The possible reason why PEI is less effective than RFA may be because lesions often have a thick capsule and therefore ethanol may not distribute through tissues.

There are several limitations in this study. First, a major limitation is in the inclusion of non-randomised studies, in which selection bias is likely to confound observations. Selection of treatment is likely to be based on individual or tumour characteristics, and thus these factors will bias and confound observations of survival. Second, this study included both RCTs and observational studies, in which study designs and type of data collection may not be comparable. However, findings were consistent among both study designs. Third, all included studies did not report our primary outcome of interest (5-year survival) and this was a particular limitation among randomised studies. Fourth, for many individual comparisons, there were either no direct comparisons or comparisons from only a small number of studies. The lack of evidence may increase the risk of bias, which could enlarge or undervalue effect size, and may explain the small inconsistency seen between direct and estimated comparisons. Thus, we should be cautious in interpreting treatment rankings for the different survival times and for different size lesions. While adverse events from treatments may differ (not evaluated in detail in this review), by examining overall survival outcomes in our review, we have taken account of both long-term potential benefits and harms from treatments. The focus of these findings should therefore be on the overall observation that RES or TR may be superior in terms of survival, rather than focusing on specific OR values for individual treatment comparisons.

In conclusion, the findings of the current Bayesian network meta-analysis indicate that RES or TR may be among the most effective therapeutic approaches for HCC for 5-year survival in both smaller (<3 cm) and larger (3–5 cm) lesions. However, evidence was of variable quality, and the majority of evidence came from non-randomised studies, which are prone to selection bias and knowledge gaps still exist. For not, at the individual level, selection of strategies should depend on patient and clinical characteristics. To facilitate generation of evidence-based recommendations for HCC therapy, and to standardise treatment approaches, further head-to-head comparisons, especially of resection and ablative therapies, are required from high-quality RCTs, with long follow-up for survival outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

HC and LL contributed equally.

Contributors: Conceived and designed the experiments: HC, T’J, LL. Performed the experiments: GT, SY, JY, DT, QZ, FC, T’J. Analysed the data: GT, SY, JY, QZ. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: QZ, FC. Wrote the manuscript: GT, SY, T’J. Critically revised and approved the final version of manuscript: DT, HC, T’J, LL. Study supervision: HC, T’J, LL.

Funding: This study was supported by the opening foundation of the State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Zhejiang University, grant NO. 2015KF06; This study was supported by the Foundation of Zhejiang Health Committee (2017KY346).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. GMaCoD C. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1269–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1118–27. 10.1056/NEJMra1001683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893–917. 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012;379:1245–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raza A, Sood GK. Hepatocellular carcinoma review: current treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:4115–27. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kishi Y, Hasegawa K, Sugawara Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and future development-improved outcomes with surgical resection. Int J Hepatol 2011;2011:1–10. 10.4061/2011/728103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazzaferro V, Bhoori S, Sposito C, et al. Milan criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis of 15 years of experience. Liver Transpl 2011;17:S44–57. 10.1002/lt.22365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ke S, Ding XM, Qian XJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma sized > 3 and ≤ 5 cm: is ablative margin of more than 1 cm justified? World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:7389–98. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu SJ. A concise review of updated guidelines regarding the management of hepatocellular carcinoma around the world: 2010-2016. Clin Mol Hepatol 2016;22:7–17. 10.3350/cmh.2016.22.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D, et al. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013;8:e76654 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xie H, Yu H, Tian S, et al. What is the best combination treatment with transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma? a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:100508 doi:10.18632/oncotarget.20119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katsanos K, Kitrou P, Spiliopoulos S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different transarterial embolization therapies alone or in combination with local ablative or adjuvant systemic treatments for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184597 10.1371/journal.pone.0184597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cucchetti A, Piscaglia F, Pinna AD, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Systemic Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Network Meta-Analysis of Phase III Trials. Liver Cancer 2017;6:337–48. 10.1159/000481314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Majumdar A, Roccarina D, Thorburn D, et al. Management of people with early- or very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: an attempted network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD011650 10.1002/14651858.CD011650.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Puhan MA, Schünemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g5630 10.1136/bmj.g5630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2011: Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie, 2009:S38. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, et al. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932–44. 10.1002/sim.3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jin ZC, Zhou XH, He J. Statistical methods for dealing with publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2015;34:343–60. 10.1002/sim.6342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Z, Wu M, Chen H, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2002;40:826–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lencioni RA, Allgaier HP, Cioni D, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: randomized comparison of radio-frequency thermal ablation versus percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology 2003;228:235–40. 10.1148/radiol.2281020718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin SM, Lin CJ, Lin CC, et al. Radiofrequency ablation improves prognosis compared with ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127:1714–23. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vivarelli M, Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, et al. Surgical resection versus percutaneous radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhotic liver. Ann Surg 2004;240:102–7. 10.1097/01.sla.0000129672.51886.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, et al. The comparative results of radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Hepatol 2005;11:59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hong SN, Lee SY, Choi MS, et al. Comparing the outcomes of radiofrequency ablation and surgery in patients with a single small hepatocellular carcinoma and well-preserved hepatic function. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:247–52. 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152746.72149.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang GT, Lee PH, Tsang YM, et al. Percutaneous ethanol injection versus surgical resection for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. Ann Surg 2005;242:36–42. 10.1097/01.sla.0000167925.90380.fe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin SM, Lin CJ, Lin CC, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection, and percutaneous acetic acid injection to treat hepatocellular carcinoma of 3 cm or less. Gut 2005;54:1151–6. 10.1136/gut.2004.045203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu MD, Xu HX, Xie XY, et al. Percutaneous microwave and radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective comparative study. J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1054–60. 10.1007/s00535-005-1671-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Montorsi M, Santambrogio R, Bianchi P, et al. Survival and recurrences after hepatic resection or radiofrequency for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: a multivariate analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:62–8. Discussion 67-8 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2005;129:122–30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2006;243:321–8. 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lü MD, Kuang M, Liang LJ, et al. Surgical resection versus percutaneous thermal ablation for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2006;86:801–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cho YB, Lee KU, Suh KS, et al. Hepatic resection compared to percutaneous ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma using propensity score matching. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;22:1643–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04902.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gao W, Chen MH, Yan K, et al. Therapeutic effect of radiofrequency ablation in unsuitable operative small hepatocellular carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Medical Imaging Technology 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lupo L, Panzera P, Giannelli G, et al. Single hepatocellular carcinoma ranging from 3 to 5 cm: radiofrequency ablation or resection? HPB 2007;9:429–34. 10.1080/13651820701713758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou T, Qiu YD, Kong WT. Comparing the effect of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for the treatment of small hepatocellar. Journal of Hepatobiliary Surgery 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abu-Hilal M, Primrose JN, Casaril A, et al. Surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of small unifocal hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1521–6. 10.1007/s11605-008-0553-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brunello F, Veltri A, Carucci P, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus ethanol injection for early hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008;43:727–35. 10.1080/00365520701885481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Valdegamberi A, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:192–8. 10.1007/s11605-007-0392-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hiraoka A, Horiike N, Yamashita Y, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency ablation therapy compared to surgical resection in 164 patients in Japan with single hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than 3 cm, along with report of complications. Hepatogastroenterology 2008;55:2171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohmoto K, Yoshioka N, Tomiyama Y, et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects between radiofrequency ablation and percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for small hepatocellular carcinomas. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:223–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05596.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sakaguchi H, Seki S, Tsuji K, et al. Endoscopic thermal ablation therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-center study. Hepatol Res 2009;39:47–52. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Santambrogio R, Opocher E, Zuin M, et al. Surgical resection versus laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh class a liver cirrhosis. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:3289–98. 10.1245/s10434-009-0678-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shibata T, Isoda H, Hirokawa Y, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: is radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization more effective than radiofrequency ablation alone for treatment? Radiology 2009;252:905–13. 10.1148/radiol.2523081676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ueno S, Sakoda M, Kubo F, et al. Surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinomas within the Milan criteria. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:359–66. 10.1007/s00534-009-0069-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xiang-Yang BU, Wang Y, Zhong GE, et al. Comparison of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for small primary liver carcinoma. Chinese Archives of General Surgery 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo WX, Zhai B, Lai EC, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus partial hepatectomy for multicentric small hepatocellular carcinomas: a nonrandomized comparative study. World J Surg 2010;34:2671–6. 10.1007/s00268-010-0732-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang J, Yan L, Cheng Z, et al. A randomized trial comparing radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection for HCC conforming to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg 2010;252:903–12. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181efc656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kagawa T, Koizumi J, Kojima S, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus radiofrequency ablation therapy for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with surgical resection. Cancer 2010;116:3638–44. 10.1002/cncr.25142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Morimoto M, Numata K, Kondou M, et al. Midterm outcomes in patients with intermediate-sized hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial for determining the efficacy of radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Cancer 2010;116:5452–60. 10.1002/cncr.25314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Azab M, Zaki S, El-Shetey AG, et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with percutaneous ethanol injection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Arab J Gastroenterol 2011;12:113–8. 10.1016/j.ajg.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Giorgio A, Di Sarno A, De Stefano G, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma compared to percutaneous ethanol injection in treatment of cirrhotic patients: an Italian randomized controlled trial. Anticancer Res 2011;31:2291–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hung HH, Chiou YY, Hsia CY, et al. Survival rates are comparable after radiofrequency ablation or surgery in patients with small hepatocellular carcinomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:79–86. 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nishikawa H, Inuzuka T, Takeda H, et al. Comparison of percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation and surgical resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol 2011;11:143 10.1186/1471-230X-11-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yun WK, Choi MS, Choi D, et al. Superior long-term outcomes after surgery in child-pugh class a patients with single small hepatocellular carcinoma compared to radiofrequency ablation. Hepatol Int 2011;5:722–9. 10.1007/s12072-010-9237-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang J, Liu HC, Zhou L. The effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of liver cancer. Journal of Hepatobiliary Surgery 2011;19:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhao M, Wang JP, Li W, et al. Comparison of safety and efficacy for transcatheter arterial chemoembolization alone and plus radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of single branch portal vein tumor thrombus of hepatocellular carcinoma and their prognosis factors. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2011;91:1167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Feng K, Yan J, Li X, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology 2012;57:794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Peng ZW, Lin XJ, Zhang YJ, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus hepatic resection for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas 2 cm or smaller: a retrospective comparative study. Radiology 2012;262:1022–33. 10.1148/radiol.11110817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Liang HH, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sequential transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and RF ablation versus RF ablation alone: a prospective randomized trial. Radiology 2012;262:689–700. 10.1148/radiol.11110637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Signoriello S, Annunziata A, Lama N, et al. Survival after locoregional treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study in real-world patients. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:1–7. 10.1100/2012/564706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang JH, Wang CC, Hung CH, et al. Survival comparison between surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation for patients in BCLC very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:412–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Desiderio J, Trastulli S, Pasquale R, et al. Could radiofrequency ablation replace liver resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with compensated cirrhosis? A 5-year follow-up. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013;398:55–62. 10.1007/s00423-012-1029-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ding J, Jing X, Liu J, et al. Comparison of two different thermal techniques for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Radiol 2013;82:1379–84. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Guo WX, Sun JX, Cheng YQ, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus partial hepatectomy for small centrally located hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2013;37:602–7. 10.1007/s00268-012-1870-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M, et al. Comparison of resection and ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a cohort study based on a Japanese nationwide survey. J Hepatol 2013;58:724–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Iida H, Aihara T, Ikuta S, et al. A comparative study of therapeutic effect between laparoscopic microwave coagulation and laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation. Hepatogastroenterology 2013;60:662–5. 10.5754/hge12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Imai K, Beppu T, Chikamoto A, et al. Comparison between hepatic resection and radiofrequency ablation as first-line treatment for solitary small-sized hepatocellular carcinoma of 3 cm or less. Hepatol Res 2013;43:853–64. 10.1111/hepr.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim JW, Shin SS, Kim JK, et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for the treatment of single hepatocellular carcinoma of 2 to 5 cm in diameter: comparison with surgical resection. Korean J Radiol 2013;14:626–35. 10.3348/kjr.2013.14.4.626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lai EC, Tang CN. Radiofrequency ablation versus hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria--a comparative study. Int J Surg 2013;11:77–80. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lin ZZ, Shau WY, Hsu C, et al. Radiofrequency ablation is superior to ethanol injection in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma irrespective of tumor size. PLoS One 2013;8:e80276 10.1371/journal.pone.0080276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Chen MS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation with or without transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:426–32. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tohme S, Geller DA, Cardinal JS, et al. Radiofrequency ablation compared to resection in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB 2013;15:210–7. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00541.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wong KM, Yeh ML, Chuang SC, et al. Survival comparison between surgical resection and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for patients in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Indian J Gastroenterol 2013;32:253–7. 10.1007/s12664-012-0225-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang L, Wang N, Shen Q, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One 2013;8:e76119 10.1371/journal.pone.0076119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Abdelaziz A, Elbaz T, Shousha HI, et al. Efficacy and survival analysis of percutaneous radiofrequency versus microwave ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an Egyptian multidisciplinary clinic experience. Surg Endosc 2014;28:3429–34. 10.1007/s00464-014-3617-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shi J, Sun Q, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of microwave ablation and surgical resection for treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas conforming to Milan criteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1500–7. 10.1111/jgh.12572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yang HJ, Lee JH, Lee DH, et al. Small single-nodule hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, and hepatic resection by using inverse probability weighting. Radiology 2014;271:909–18. 10.1148/radiol.13131760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhang T, Li K, Luo H, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous microwave ablation versus repeat hepatectomy for treatment of late recurrent small hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2014;94:2570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Pompili M, De Matthaeis N, Saviano A, et al. Single hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than 2 cm: are ethanol injection and radiofrequency ablation equally effective? Anticancer Res 2015;35:325–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xu J, Zhao Y. Comparison of percutaneous microwave ablation and laparoscopic resection in the prognosis of liver cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:11665–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lee HW, Lee JM, Yoon JH, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing radiofrequency ablation and hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018;94:74–82. 10.4174/astr.2018.94.2.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li W, Zhou X, Huang Z, et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic hepatectomy, microwave ablation, and open hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma: a 5-year experience in a single center. Annals of surgical treatment and research 2017;47:650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, et al. Surgical resection versus radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 2 cm in a propensity score model. Ann Surg 2016;263:538–45. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Liu H, Wang ZG, Fu SY, et al. Randomized clinical trial of chemoembolization plus radiofrequency ablation versus partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Br J Surg 2016;103:348–56. 10.1002/bjs.10061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hof J, Wertenbroek MW, Peeters PM, et al. Outcomes after resection and/or radiofrequency ablation for recurrence after treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 2016;103:1055–62. 10.1002/bjs.10162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Vogl TJ, Farshid P, Naguib NN, et al. Ablation therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparative study between radiofrequency and microwave ablation. Abdom Imaging 2015;40:1829–37. 10.1007/s00261-015-0355-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lee YH, Hsu CY, Chu CW, et al. Radiofrequency ablation is better than surgical resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria and preserved liver function: a retrospective study using propensity score analyses. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:242–9. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kang TW, Kim JM, Rhim H, et al. Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma: radiofrequency ablation versus nonanatomic resection--propensity score analyses of long-term outcomes. Radiology 2015;275:908–19. 10.1148/radiol.15141483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zhou Z, Lei J, Li B, et al. Liver resection and radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma cases (single nodule <2 cm): a single-center study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:339–44. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ko S, Jo H, Yun S, et al. Comparative analysis of radiofrequency ablation and resection for resectable colorectal liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:525–31. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i2.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kim JM, Kang TW, Kwon CH, et al. Single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 3 cm in left lateral segment: liver resection or radiofrequency ablation? World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:4059–65. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Agcaoglu O, Aliyev S, Karabulut K, et al. Complementary use of resection and radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of colorectal liver metastases: an analysis of 395 patients. World J Surg 2013;37:1333–9. 10.1007/s00268-013-1981-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Goldberg SN, Girnan GD, Lukyanov AN, et al. Percutaneous tumor ablation: increased necrosis with combined radio-frequency ablation and intravenous liposomal doxorubicin in a rat breast tumor model. Radiology 2002;222:797–804. 10.1148/radiol.2223010861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Taub R. Liver regeneration: from myth to mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004;5:836–47. 10.1038/nrm1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Martins PN, Theruvath TP, Neuhaus P. Rodent models of partial hepatectomies. Liver Int 2008;28:3–11. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kele PG, de Boer M, van der Jagt EJ, et al. Early hepatic regeneration index and completeness of regeneration at 6 months after partial hepatectomy. Br J Surg 2012;99:1113–9. 10.1002/bjs.8807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Preziosi ME, Monga SP. Update on the mechanisms of liver regeneration. Semin Liver Dis 2017;37:141–51. 10.1055/s-0037-1601351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Morise Z, Kawabe N, Tomishige H, et al. Recent advances in liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Surg 2014;1:21 10.3389/fsurg.2014.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021269supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)