Abstract

Objectives

We aim to study the preferred behaviour among individuals from different age groups in three countries when acute health problems occur outside office hours and thereby to explore variations in help-seeking behaviour.

Design

A questionnaire study exploring responses to six hypothetical cases describing situations with a potential need for seeking medical care and questions on background characteristics.

Setting

General population in Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland.

Population

Danish, Dutch and Swiss individuals from three age groups (0–4, 30–39, 50–59 years).

Main outcome measures

Distribution of intended help-seeking preferences per case per age group, compared between countries. Differences in percentage of help-seeking outside office hours per age group and country, crude and adjusted for background characteristics.

Results

Danish and Dutch parents of children aged 0–4 years differed in intended help-seeking behaviour for five out of six cases (abdominal pain, red eyes, rash, relapse fever, chickenpox); Danish parents significantly more often chose to contact out-of-hours (OOH) care than Dutch parents. For adults aged 30–39 years, no significant difference between the three countries was found for contacting OOH care. Swiss adults aged 50–59 years had the highest percentage of OOH contacts (38.3%), followed by the Danish (33.4%) and the Dutch (32.5%).

Conclusion

Some differences in help-seeking behaviour outside office hours exist between Danish, Dutch and Swiss individuals, particularly for parents of young children. The question remains whether these differences result from individual preferences, cultural disparities and/or health services variations. Future research should focus on identifying explanations for these differences to reduce undesirable use of OOH care.

Keywords: after-hours care, primary health care, help-seeking behavior

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is based on representative population samples from three countries.

An extensive procedure was followed to ensure high quality of the case development.

Using hypothetical cases to measure intended help-seeking behaviour could have introduced social desirability bias, and the responses may thus not represent actual behaviour.

The choice of cases could have affected the results.

Introduction

Many European countries face high demands in out-of-hours (OOH) care, for example, primary care, emergency departments (EDs) and emergency medical services (EMS).1–3 This can lead to high workload, excessive use of resources and increased costs.4–6 High workload may lead to longer waiting times, work pressure for OOH staff and risk of safety incidents. At the same time, the service delivery by general practitioners (GPs) to OOH primary care is challenged due to fewer available GPs, low work satisfaction and need for off-duty time.7

The help-seeking behaviour among individuals varies between European countries, with differing numbers of ED visits and GP consultations.8–10 The number of GP consultations per patient ranges from 2.9 to 11.8 per year in European countries,9 whereas the proportion of patients who visited the ED in the past year varied between 18% and 40%.8 Similar differences also seem apparent in OOH primary care. In a previous study, we found differences in help-seeking behaviour between Danish and Dutch individuals; the Danish individuals contacted OOH primary care about twice as often as the Dutch.11

Differences between countries may be related to the organisation of healthcare systems and OOH care (such as fees, accessibility and availability), the composition of populations,12 culture and/or public expectations to healthcare services. Exploring differences in help-seeking behaviour could be a first step to identify factors with a potential for intervention to optimise help-seeking behaviour and requests. Thus, we aim to study how individuals from different age groups in three countries (ie, Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland) react to hypothetical scenarios about acute health problems occurring outside office hours.

Methods

Design and population

We performed a questionnaire study exploring responses to hypothetical cases by sending questionnaires with hypothetical paper case scenarios to Danish, Dutch and Swiss individuals in December 2015 and January 2016. This study was part of a project of the European research network for OOH primary healthcare (EurOOHnet).13 Simultaneously, a second paper has been written on factors related to intended help-seeking OOH.14 We included a random selection of individuals from three age groups (ie, parents of children aged 0–4 years, adults aged 30–39 years and adults aged 50–59 years). Predefined age groups were preferred to ensure construction of explicit cases and to obtain sufficient power for identifying differences for each separate age group. Age groups were based on a previous study which found the largest differences in the use of OOH care to be between Danish and Dutch individuals for both age groups, 0–4 years and 20–35 years.11 We composed the age group of individuals aged 30–39 years as we expected more homogeneity in this group than in the group of individuals aged 25–35 years. In this study, we added the age group 50–59 years to examine the robustness of our results.

We used the Danish Civil Registration System to randomly select representative individuals among the five Danish regions. We excluded individuals living in institutions and individuals with address protection. The Dutch and Swiss samples were selected using consumer panels (the Netherlands: TNS Nipo; Switzerland: Respondi and Bilendi).15–17 The Dutch sample represented the population on age, gender and region (0–4 years), and age, gender, region, education and ethnicity (both adult age groups). For Switzerland, it was only possible to include adults selected on age by using two panels to reach 600 respondents as information about children of panel members was not available.

Settings

In Denmark, 99% of citizens are listed with a GP. Through the GP, they have access to the entire public (tax-funded) healthcare system which is free of charge for the patients.18 Outside office hours, patients can contact OOH primary care or the prehospital EMS, depending on the severity and urgency of the health problem. Referral from either primary care or EMS is generally a prerequisite for an ED visit, specialist care or hospital admission, although self-referral to the ED exists. For most OOH primary care services, GPs perform the telephone triage and are remunerated on a fee-for-service basis. The Netherlands has a similar system, with the GP serving as a gatekeeper.19 Citizens must have private health insurance which gives free access to primary care throughout and outside office hours. Nurses and practice assistants answer the telephone in the Dutch OOH primary care services and perform the triage under supervision by GPs. All professionals working in OOH primary care get paid per hour. A referral is usually a prerequisite for access to the ED and hospital visits, although self-referral to the ED exists. In Switzerland, OOH care is organised locally, and organisational models vary between regions. The most widespread models include rotation systems which are most often combined with EMS telephone triage, walk-in centres (eg, group practices offering OOH care) and general practices integrated in the ED. No gatekeeping system exists, and referral from a GP is thus not needed for access to the ED and specialist care. OOH care is covered by the mandatory health insurance plan, except for an annual deductible rate ranging between SFr300 to SFr2500 (€275 to €2300) and a 10% copayment.

Development of questionnaires

We developed questionnaires containing hypothetical cases that described situations with a potential acute need for medical care outside office hours. As a measure of urgency, all cases varied in the type of care needed (online supplementary appendix). The questionnaires for children and adults mainly differed on presented cases. The questionnaires also included questions on background characteristics (ie, age, sex, social support, living status, education level, employment and ethnicity) and on factors related to help-seeking based on Andersen’s behavioural model.12 The questions on factors related to help-seeking were part of a larger study and will be described in further detail in another scientific article focusing on factors related to intended help-seeking outside office hours.

bmjopen-2017-019295supp001.pdf (283KB, pdf)

Cases

The development of cases followed several steps: collecting and selecting relevant and representative cases, assessing the type of care needed (performed by an expert panel) and making the final selection using Rasch analysis. We collected cases from previous studies.20–22 We also added new cases to include frequent reasons for encounter (based on an analysis of data from Danish and Dutch OOH primary care) and to ensure that we included cases from all urgency levels (based on the telephone guideline from the Dutch Association of GPs to categorise the cases).23 We selected different health problems for the cases for each age group separately to ensure that the urgency levels were not immediately obvious. For cases regarding children, we defined a specific age for the child as even small age differences in this group can change the help-seeking behaviour considerably for the same illness. For the adults, no specific age was presented as the individuals were intended to see themselves in the described situation. All cases included a specific weekday and time. The list of potentially relevant cases was discussed at several internal meetings with researchers and GPs (to ensure representativeness of cases) and in two feedback rounds by email involving eight lay persons and five academic GPs (to check for recognisability and clarity). We selected 20 cases involving children and 32 cases involving adults to be presented for the expert panel. The relevance of the health problems described was checked and found relevant for the Swiss healthcare system. In this process, we used cases written in English.

We sent the cases to a convenience sample of 29 GPs using the following inclusion criteria: ≥2 years GP experience, ≥6 OOH shifts per year, varying regions within the countries and good knowledge of English. This expert panel assessed the most appropriate type of care needed per case to enable us to include cases of different levels of urgency.

After the expert round, we ranked the cases on type of care needed as we aimed to select cases that represented different levels of care with only a few cases per urgency level. We excluded cases that appeared to be unclear. We selected 11 cases for children and 13 cases for adults; these numbers were estimated to be sufficient for selection of cases to be included in the final questionnaire after additional analysis.

The cases were then translated from English into Danish. To ensure high quality of the translation, we followed the standard translation procedure in healthcare: backward–forward translation with a subsequent consensus meeting before creating the final document.24 The cases were randomly ranked, and questions on background characteristics were added to the questionnaires. Individuals were asked about their expected choice of action per case, and each question had the following multiple-choice answering categories: ‘Wait and see (no contact with a healthcare provider)’, ‘Self-care (for example a pain killer)’, ‘Ask my partner, a relative or others for advice’, ‘Check a guidebook, the internet or an app’, ‘Contact my own GP the next working day’, ‘Contact OOH primary care’, ‘Contact the ED’, ‘Contact 112/144 ambulance care’ and ‘Other’. Questionnaires were sent to 150 Danish individuals per age group (with one reminder). A total of 18 parents and 30 adults (11 aged 30–39 years and 19 aged 50–59 years) responded. The cases were treated as items in a Rasch analysis. This was done to eliminate redundant cases with respect to estimating the latent variable for intention to seek help. Cases were reduced, and we selected six cases for children and six for adults.

Pilot testing

We tested the readability and feasibility of the Danish questionnaires by performing cognitive interviews and pilot testing. Due to pragmatic considerations, we performed only one pilot test in Denmark. After interviewing eight patients at a GP practice, we sent the questionnaire to 50 Danish individuals per age group (with one reminder). The response rate was 38% for 0–4 years, 28% for 30–39 years and 50% for 50–59 years. The pilot testing resulted in minor adjustments of layout. The final Danish questionnaire was translated into Dutch and German using the usual translation procedure.24

Power calculation

A power calculation showed that we needed 600 returned questionnaires per age group to be able to find an 8% difference between countries which we considered a clinically relevant difference. Expecting an average response rate of 40%, we chose to send 1200 questionnaires per age group in the Danish population. The Dutch panel expected higher response rate and aimed to collect 600 returned questionnaires per age group within 1 week of data collection. The Swiss panel invited all members in the adult groups and stopped the data collection when 600 respondents had been reached.

Data collection

The Danish individuals received an invitation letter with a personal internet link to a web-based survey and a paper questionnaire in January 2016. One reminder was sent 3 weeks later. Dutch individuals received an email invitation to the online questionnaire in December 2015. One reminder was sent for age groups 0–4 and 30–39 years to achieve 600 respondents per group, whereas no reminder was needed for age group 50–59 years. The data collection ended after 1 week. Swiss individuals received their invitation via email in December 2015, and the data collection ended when 600 respondents had been included per age group.

Analysis

We performed descriptive analyses of the Danish respondents and non-respondents and identified the main characteristics for each age group as the Danish selection was random. We also performed descriptive analyses to compare respondents with the general population in the Netherlands and Switzerland. This was done because we wanted to check the representativeness of the consumer panels that we used in these two countries. Next, we calculated the distribution of the individual help-seeking behaviour per case and stratified for age group and country to investigate intended help-seeking behaviour.

We dichotomised the intended help-seeking behaviour into ‘no OOH contact’ (‘Wait and see’, ‘Self-care’, ‘Ask my partner, a relative or others for advice’, ‘Check a guidebook, the internet or an app’, ‘Contact my own GP the next working day’) and ‘OOH contact’ (‘Contact OOH primary care’, ‘Contact ED’, ‘Contact 112/144 ambulance care’). After calculating the percentage of individuals contacting OOH care, we studied differences between Danish, Dutch and Swiss individuals per case and age groups by using χ2 and analysis of variance tests. For each respondent, we calculated a score between 0 and 6 for the cases in which ‘OOH contact’ had been chosen. Finally, we performed three linear regression analyses for each age group to see if there were any differences between the Danish, Dutch and Swiss individuals regarding their choice to contact OOH care using the mean score (range 0–6). We adjusted for background characteristics (ie, age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment and living status). Differences with a p value of <0.05 were considered significant.

Patient involvement

The study was conducted using a random selection of citizens, who were all potential users of the healthcare system (patients). We asked eight lay persons to check the cases for recognisability and clarity. A selection of citizens got a questionnaire as part of our pilot study. We have no fixed plans to disseminate our study results to citizens, although we hope that the results will be used for interventions to influence use of OOH care, for example, to inform patients. If possible, dissemination of results in lay press will be done.

Results

Study population

Table 1 describes the final respondents of our study after data cleaning. In Denmark, we included 572 respondents for children (response rate: 47.7%), 429 for 30–39 years (response rate: 35.8%) and 652 for 50–59 years (response rate: 54.4%). In the Netherlands, we included 621 respondents for children (response rate: 65.4%), 592 for 30–39 years (response rate: 62.3%) and 633 for 50–59 years (response rate: 66.5%). The Swiss panel included 589 final respondents for age group 30–39 years and 595 for age group 50–59 years. However, due to the data collection strategy, we obtained no information on response rate for the Swiss panel. When comparing respondents in different age groups between countries, we found some significant (although small) differences for gender, age and ethnicity for respondents of age group 0–4 years (table 1). For both adult age groups, we found significant differences for gender (Dutch respondents were more often female), education (Dutch aged 50–59 years more often had low education level) and ethnicity (Swiss respondents were more often immigrants).

Table 1.

Description of the study population per age group and country

| Age group | 0–4 years* | 30–39 years | 50–59 years | |||||

| Country | DK n=572 |

NL n=621 |

DK n=429 |

NL n=592 |

CH n=589 |

DK n=652 |

NL n=633 |

CH n=595 |

| Age respondent (mean (95% CI)) | 34.4 (34.0 to 34.8) | 35.4 (34.9 to 35.8) | 34.8 (34.6 to 35.1) | 34.8 (34.6 to 35.0) | 34.9 (34.7 to 35.2) | 54.4 (54.1 to 54.6) | 54.6 (54.4 to 54.8) | 54.5 (54.2 to 54.7) |

| Gender respondent (% (95% CI)) | ||||||||

| Male | 14.4 (11.7 to 17.5) | 37.7 (33.9 to 41.6) | 37.7 (33.2 to 42.4) | 50.2 (46.1 to 54.2) | 42.3 (38.3 to 46.3) | 44.9 (41.1 to 48.8) | 52.9 (49.0 to 56.8) | 48.1 (44.1 to 52.1) |

| Female | 85.6 (82.5 to 88.3) | 62.3 (58.4 to 66.1) | 62.4 (57.6 to 66.8) | 49.8 (45.8 to 53.9) | 57.7 (53.7 to 61.7) | 55.1 (51.2 to 58.9) | 47.1 (43.2 to 51.0) | 51.9 (47.9 to 55.9) |

| Education level† (% (95% CI)) | ||||||||

| Low: ≤10 years | 4.4 (3.0 to 6.4) | 7.0 (5.2 to 9.3) | 6.4 (4.4 to 9.1) | 9.3 (7.2 to 11.9) | 4.6 (3.2 to 6.6) | 13.5 (11.0 to 16.3) | 25.4 (22.2 to 29.0) | 9.7 (7.6 to 12.4) |

| Middle: >10 and ≤15 years | 33.5 (29.7 to 37.4) | 30.1 (26.6 to 33.9) | 41.0 (36.4 to 45.8) | 43.4 (39.5 to 47.4) | 55.0 (51.1 to 58.8) | 55.0 (51.1 to 58.8) | 43.9 (40.1 to 47.8) | 66.1 (62.1 to 69.7) |

| High: >15 years | 62.1 (58.1 to 66.1) | 62.9 (59.0 to 66.6) | 52.6 (47.8 to 57.3) | 47.3 (43.3 to 51.3) | 36.1 (32.3 to 40.0) | 31.6 (28.1 to 35.3) | 30.6 (27.2 to 34.4) | 24.2 (20.9 to 27.8) |

| Ethnicity (% (95% CI)) | ||||||||

| Native | 85.5 (82.3 to 88.2) | 81.8 (78.5 to 84.6) | 84.8 (81.0 to 87.9) | 76.1 (72.5 to 79.4) | 64.3 (60.4 to 68.1) | 92.0 (89.6 to 93.9) | 87.1 (84.2 to 89.5) | 70.3 (66.4 to 73.8) |

| Western immigrant | 10.2 (8.0 to 13.0) | 7.4 (5.6 to 9.8) | 9.0 (6.6 to 12.2) | 10.2 (8.0 to 13.0) | 31.6 (27.9 to 35.5) | 6.4 (4.8 to 8.6) | 9.1 (7.1 to 11.6) | 27.9 (24.4 to 31.6) |

| Non-western immigrant | 4.3 (2.9 to 6.3) | 10.8 (8.6 to 13.5) | 6.2 (4.2 to 8.9) | 13.7 (11.1 to 16.7) | 4.1 (2.8 to 6.0) | 1.6 (0.8 to 2.9) | 3.8 (2.6 to 5.6) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.3) |

*Switzerland had no age group 0–4 years, due to restrictions of the consumer panels.

†This categorisation was made according to the ISCED guidelines.33

CH, Switzerland; DK, Denmark; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education; NL, Netherlands.

We compared the Danish respondents and non-respondents. For the age groups 30–39 years and 50–59 years, we found that respondents were more often female (online supplementary appendix table 1). The Dutch respondents were compared with the general population. Adult respondents were slightly more often highly educated and native Dutch compared with the general population (online supplementary appendix table 2). The Swiss respondents were also compared with the general population. Swiss respondents were more often female, had middle-level education and were native Swiss (online supplementary appendix table 3).

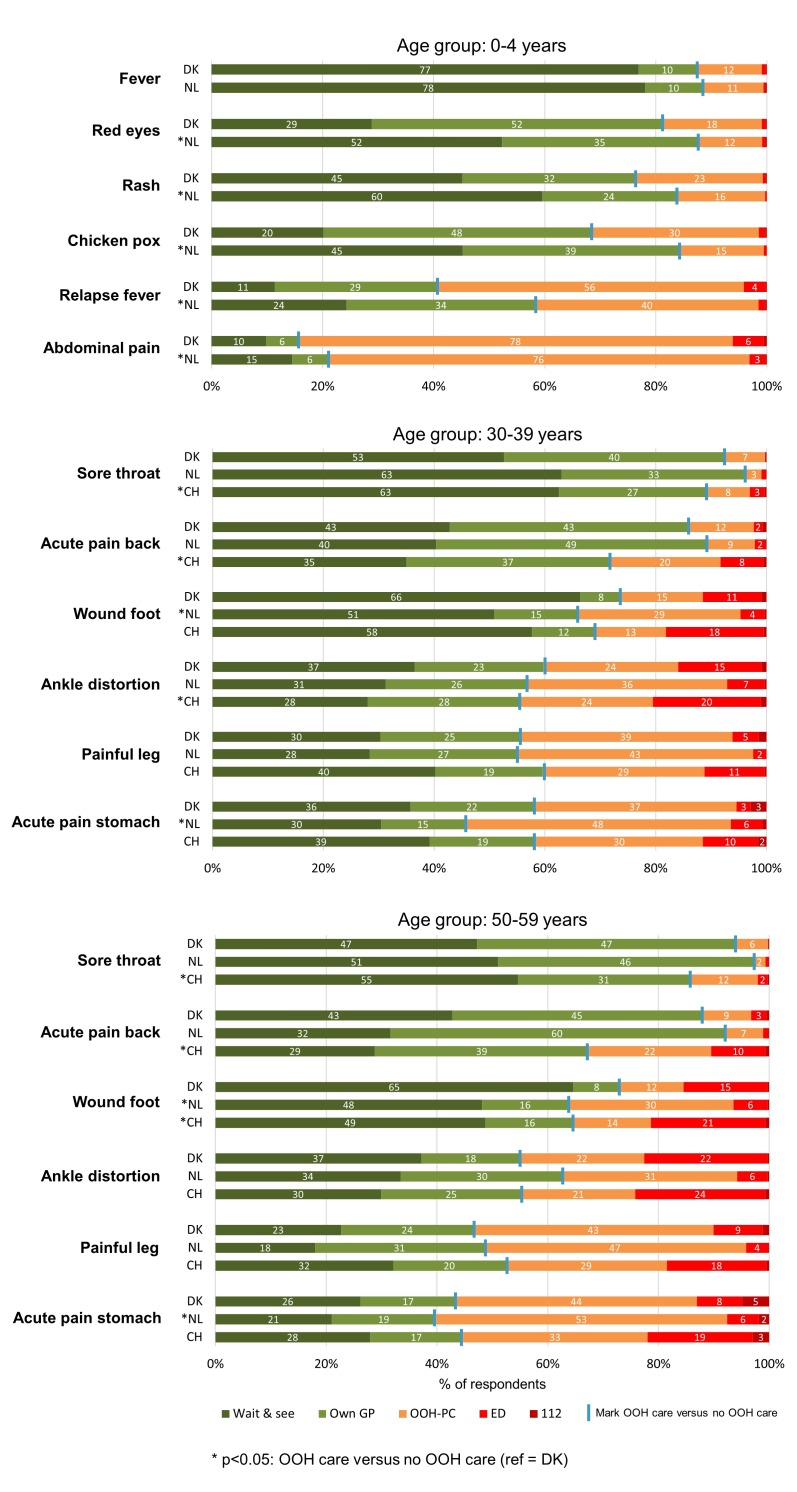

Help-seeking at case level: children

Figure 1 shows help-seeking behaviour per age group, per case and per country. Danish and Dutch parents differed in their intended help-seeking in most of the presented cases. The Dutch parents chose ‘wait and see’ more often than the Danish parents, who more often answered that they would contact their own GP or OOH primary care. Overall, the Danish parents chose to contact OOH acute care more often than Dutch parents, with significant differences for the following five cases: for ‘red eyes’, 18.7% of the Danish parents chose to contact OOH acute care, compared with 12.4% among Dutch parents; for ‘rash’, 23.4% of Danish and 16.4% of Dutch parents would contact OOH acute care; for ‘chickenpox’, 31.8% of Danish and 15.8% of Dutch parents would contact OOH acute care; for ‘relapse fever’, 59.5% of Danish and 41.6% of Dutch parents would contact OOH acute care; for ‘abdominal pain’, 84.4% of Danish and 79.1% of Dutch parents would contact OOH acute care.

Figure 1.

Description of individuals help-seeking per case, stratified for age group and country (distribution of choices). CH, Switzerland; DK, Denmark; ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; NL, Netherlands; OOH-PC, out-of-hours primary care.

Help-seeking at case level: adults

We also found some differences in intended help-seeking behaviour among adults from different countries (figure 1). In the age group 30–39 years, the Swiss more often chose to contact the ED than Danish and Dutch adults. Overall, the choices for different types of care varied per case. Additionally, adults aged 30–39 years differed in the frequency of contacting OOH acute care, with varying differences per case. For ‘sore throat’ (Danish: 7.5%, Dutch: 3.6%, Swiss: 10.9%), ‘acute back pain’ (Danish: 14.1%, Dutch: 10.8%, Swiss: 28.4%) and ‘ankle distortion’ (Danish: 40.3%, Dutch: 43.1%, Swiss: 44.3%), the Swiss adults significantly more often chose to contact OOH care than the Danish and Dutch, although with relatively small differences. For ‘wounded foot’ (Danish: 26.1%, Dutch: 34.0%, Swiss: 30.8%) and ‘acute stomach pain’ (Danish: 42.0%, Dutch: 54.4%, Swiss: 41.6%), Dutch adults significantly more often chose to contact OOH care.

In the age group 50–59 years, the Swiss also more often chose to contact the ED compared with the Danish and Dutch adults in this group. No clear pattern was seen for the other types of care. The Swiss adults more often chose to contact OOH care for two cases: ‘sore throat’ (Danish: 5.7%, Dutch: 2.7%, Swiss: 14.1%) and ‘acute back pain’ (Danish: 12.1%, Dutch: 8.1%, Swiss: 32.5%). For ‘wounded foot’, the Dutch and Swiss adults significantly more often chose to contact OOH care than the Danish adults (Danish: 26.1%, Dutch: 34.0%, Swiss: 30.8%). The Dutch significantly more often chose OOH care for ‘acute stomach pain’ (Danish: 42.0%, Dutch: 54.4%, Swiss: 41.6%).

Adjusted differences in help-seeking

Table 2 shows that the Dutch parents significantly less often chose to contact OOH care than Danish parents (mean: 2.25 vs 2.91 out of 6 cases). For adults aged 30–39 years, no significant differences were found between the three countries when correcting for age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment and living status. Swiss adults aged 50–59 years more often chose to contact OOH care than the Danish (mean: 2.58 vs 2.34 out of 6 cases).

Table 2.

Association between country and out-of-hours help-seeking per age group

| 0–4 years | 30–39 years | 50–59 years | ||||

| Crude n=1186 |

Adjusted† n=1161 |

Crude n=1602 |

Adjusted† n=1585 |

Crude n=1864 |

Adjusted† n=1844 |

|

| Denmark (ref) (mean (95% CI)) | 2.31 (2.20 to 2.42) | 2.91 (2.53 to 3.30) | 1.75 (1.61 to 1.89) | 2.15 (1.78 to 2.51) | 2.00 (1.89 to 2.12) | 2.34 (1.90 to 2.77) |

|

Netherlands

(*, mean (95% CI)) |

−0.54* 1.78 (1.66 to 1.87) |

−0.66* 2.25 (1.87 to 2.63) |

0.16 1.91 (1.79 to 2.02) |

0.11 2.26 (1.90 to 2.61) |

−0.04 1.96 (1.84 to 2.07) |

−0.10 2.24 (1.81 to 2.66) |

|

Switzerland

(*, mean (95% CI)) |

Not available | Not available | 0.22* 1.97 (1.85 to 2.09) |

0.16 2.31 (1.94 to 2.68) |

0.29* 2.30 (2.18 to 2.41) |

0.24* 2.58 (2.14 to 3.02) |

*Significant difference (p<0.05) compared with reference group.

†Adjusted for age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment and living status.

Discussion

Main findings

Danish and Dutch parents of children aged 0–4 years differed in help-seeking behaviour for five out of six cases (ie, abdominal pain, red eyes, rash, relapse fever, chickenpox); the Dutch more often chose ‘wait and see’ than the Danish. For these cases, Danish parents significantly more often chose to contact OOH care than Dutch parents (difference varying from 1.1% to 17.9%). Also a regression analysis showed that Dutch parents significantly less often chose to contact OOH care than Danish parents. For adult citizens, we found varying choices of responses for many of the presented cases. A regression analysis showed that the Swiss adults aged 50–59 years more often chose OOH care than the Danish and Dutch.

Comparison with existing literature

We found a difference in help-seeking behaviour between Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland; this difference was varying for different age groups. In a previous study, we found that the Danish individuals had higher consumption of OOH primary care than the Dutch, particularly for young children.11 This difference between parents of young children was also apparent in our study. The question is what the underlying explanations could be for this consistent difference. A difference in employment exists between Danish and Dutch parents as Danish women more frequently are working full-time.25 Danish women thus have fewer opportunities to visit the GP during daytime. Furthermore, the role of the Danish GP in childcare is different from that of the Dutch GP. Danish GPs have an active role as they also see young children for preventive issues which could make parents more prone to contact primary care. In contrast, Dutch GPs do not play a role in preventive care for young children. Perhaps other cultural differences may be important factors. For example, there is a strong focus on work–life balance in Denmark (including extensive maternity leave). Differences between the Danish and the Dutch healthcare systems may play a smaller role as we did not find any differences in the help-seeking between adults. Besides, the two healthcare systems seem quite similar. Yet, the direct telephone access to a GP (who answers the telephone) in the OOH primary services in Denmark may encourage parents to seek advice or help at the OOH primary care service. Additionally, problems with the accessibility and availability of one’s own GP are also issues that are discussed in both countries.

We did not find a significant difference in help-seeking between Danish and Dutch adults, while a previous study showed a small difference between Danish and Dutch adults.11 Yet, we found a difference for Swiss adults aged 50–59 years who more often chose to contact OOH care than Danish and Dutch adults. Swiss adults more often answered ‘wait and see’, but they also more often chose ‘ED’. The difference in healthcare systems (with or without gatekeeping) seems to influence the intended help-seeking behaviour. The organisation of the Swiss healthcare system without the gatekeeping role of the GP may make citizens contact the ED more often, in particular for injury-related health problems which were described in three of the six cases targeting adults.26 In Denmark and the Netherlands, patients are strongly encouraged to contact primary care in case of an acute problem in order to assess the necessity of a subsequent referral to ED or secondary care. In the Netherlands, contacting the ED without a referral results in a fee for the citizen (own risk) as these ED visits are not covered by the health insurance. For Danish citizens, an ED visit is free, but citizens are strongly encouraged to first contact primary care, where triage is done. A healthcare system based on gatekeeping may thus lead to less (unnecessary) use of the ED, but not necessarily to lower use of OOH care in general.

Help-seeking behaviour is related to many factors, as also found by Andersen.12 We focused on differences between countries and corrected for main variations between the populations (ie, age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment and living status). Several studies have shown an effect of these characteristics on help-seeking behaviour.27 Yet, several other influential factors have also been identified, such as psychological characteristics and usual behaviour.12 It could be that population differences relating to other factors may cause the variation between countries concerning help-seeking behaviour.

Strengths and limitations

The chosen design of using invented cases to measure intended help-seeking behaviour had several strengths and limitations. Strengths were that the respondents received the same cases, making comparisons more straightforward, and that persons who do not use OOH care or healthcare at all were also included. A limitation was the risk of introducing social desirability bias, with the response not representing actual behaviour. Additionally, the absence of emotional reactions that occur in real-life situations could have influenced the response. However, according to the theory of planned behaviour, behaviour is mainly determined by behavioural intentions.28 A review of literature on theory of planned behaviour concluded that behavioural intentions do predict behaviour,29 while Nagai found that help-seeking intentions are an important predictor of help-seeking behaviour.30 Several studies used hypothetical case scenarios in OOH care and other settings.10 31 32 Thus, we found that the chosen design was the most feasible and appropriate in relation to our aim.

OOH care is a complex issue, which currently faces challenges in many European countries. We were able to include citizens from three countries for our study by using a consumer panel in two countries. Our Danish sample was representative of the general population, and our Dutch and Swiss panels were also able to select quite representative samples for a range of background characteristics although some small statistically significant differences existed. We followed an extensive procedure to ensure high quality of the case development which is a strength of this study. However, the varying relatively low response rates and the data collection method through consumer panels (ending the collection when about 600 respondents had been included) introduced a risk of selection bias. Additionally, our non-response analyses showed that adult respondents more often were female than non-respondents. Respondents also seemed to be higher educated and were more often native citizens than the general population. Therefore, we adjusted for these background factors in our final analyses. We found some differences in the intended help-seeking between the three countries after correcting for differences in several background variables. Yet, different recruitment methods may have introduced some bias, although the effect on differences between the countries and differences between populations and culture remains unclear.

We used six cases per age group, and the selected cases represented varying health problems with different levels of severity and appropriate healthcare actions. The choice of cases could have affected the differences found. Other health problems may thus have given different results, for example, due to differences in culture, traditional treatment or the healthcare system. However, for the age group 0–4 years, the results for the individual cases all showed the same trend which suggests that case selection is a minor problem. For adults, the direction of differences varied per case. For the three cases on acute injuries, the organisation of healthcare may have played a role. The use of three age groups with varying results limited the generalisability of our results to the entire population of the included countries. The results could be rather different for other groups, such as the elderly. Finally, to obtain an 8% difference between groups, we needed 600 respondents; this was not achieved for all age groups.

Implications for research and/or practice

We compared help-seeking behaviour between countries and found some differences. Further investigation of possible explanations for these differences is highly relevant, in particular concerning parents of young children. The differences were distinct in this group, and the use of OOH primary care is known to be high in this age group.11 Identifying explanations for the differences found may help us reduce the use of OOH care in this group of patients.

Future research should also focus on other factors related to a high likelihood of contacting OOH care as this insight could be used to investigate whether interventions could be made to reduce the workload at OOH care while still addressing the highly relevant contacts. It could be interesting to see if differences in preferred actions also exist between healthcare professionals from different countries as this could imply differences in the approach to healthcare provision and cultural variations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all general practitioners and citizens for their time and input to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: LH designed the study, performed the data collection, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. EK participated in designing the study and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. AHC performed statistical analyses and critically revised the manuscript. GM and MS participated in the interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript. OS performed the data collection and critically revised the manuscript. MBC designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Danish foundation TrygFonden.

Disclaimer: TrygFonden had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J.no. 2013-41-2104). According to Danish law, approval from the Committee on Health Research Ethics of the Central Denmark Region was not needed as the study did not include biomedical intervention. The Research Ethics Committee of the Radboud University Medical Center (CMO Arnhem-Nijmegen) was consulted and concluded that the study did not fall within the remit of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) (file number: 2013/379). According to current Swiss law on human research, anonymously collected data require no approval by a regional ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset will be available on request.

References

- 1. Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huibers LA, Moth G, Bondevik GT, et al. Diagnostic scope in out-of-hours primary care services in eight European countries: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:30 10.1186/1471-2296-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lowthian JA, Cameron PA, Stoelwinder JU, et al. Increasing utilisation of emergency ambulances. Aust Health Rev 2011;35:63–9. 10.1071/AH09866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:106–15. 10.1111/jnu.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smits M, Keizer E, Huibers L, et al. GPs’ experiences with out-of-hours GP cooperatives: a survey study from the Netherlands. Eur J Gen Pract 2014;20:196–201. 10.3109/13814788.2013.839652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tekwani KL, Kerem Y, Mistry CD, et al. Emergency department crowding is associated with reduced satisfaction scores in patients discharged from the emergency department. West J Emerg Med 2013;14:11–15. 10.5811/westjem.2011.11.11456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grol R, Giesen P, van Uden C. After-hours care in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and the Netherlands: new models. Health Aff 2006;25:1733–7. 10.1377/hlthaff.25.6.1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van den Berg MJ, van Loenen T, Westert GP. Accessible and continuous primary care may help reduce rates of emergency department use. An international survey in 34 countries. Fam Pract 2016;33:42–50. 10.1093/fampra/cmv082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. OECD. Doctors’ consultations. Total, Per capita, 2014. 2014. https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/doctors-consultations.htm (accessed 29 Mar 2017).

- 10. van Loenen T, van den Berg MJ, Faber MJ, et al. Propensity to seek healthcare in different healthcare systems: analysis of patient data in 34 countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:465 10.1186/s12913-015-1119-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huibers L, Moth G, Andersen M, et al. Consumption in out-of-hours health care: Danes double Dutch? Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:44–50. 10.3109/02813432.2014.898974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc 1973;51:95–124. 10.2307/3349613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huibers L, Philips H, Giesen P, et al. EurOOHnet-the European research network for out-of-hours primary health care. Eur J Gen Pract 2014;20:229–32. 10.3109/13814788.2013.846320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keizer E, Christensen MB, Carlsen AH, et al. Factors related to out-of-hours help-seeking for acute health problems: a survey study using case scenarios. Under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Respondi consumer panel. https://www.respondi.com/

- 16. TNS Nipo consumer panel. http://www.tns-nipo.com/

- 17. Bilendi consumer panel. http://www.bilendi.co.uk/static/studymarket

- 18. Olesen F, Jolleys JV. Out of hours service: the Danish solution examined. BMJ 1994;309:1624–6. 10.1136/bmj.309.6969.1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smits M, Rutten M, Keizer E, et al. The development and performance of after-hours primary care in the Netherlands: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:737–42. 10.7326/M16-2776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giesen P, Ferwerda R, Tijssen R, et al. Safety of telephone triage in general practitioner cooperatives: do triage nurses correctly estimate urgency? Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:181–4. 10.1136/qshc.2006.018846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huibers L, Sloot S, Giesen P, et al. Wetenschappelijk onderzoek Nederlands Triage Systeem [Scientific research Netherlands Triage System]. Nijmegen, Rotterdam: IQ healthcare Radboudumc, Erasmus MC Sophia Kinderziekenhuis, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smits M, Hanssen S, Huibers L, et al. Telephone triage in general practices: a written case scenario study in the Netherlands. Scand J Prim Health Care 2016;34:28–36. 10.3109/02813432.2016.1144431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. NHG-TriageWijzer. National triage guidelines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Recommendations for the Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the DASH and Quick DASH Outcome Measures. Toronto: Institute for Work and Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25. OECD. Part-time employment rate. https://data.oecd.org/emp/part-time-employment-rate.htm#indicator-chart (accessed 6 Apr 2017).

- 26. Chmiel C, Huber CA, Rosemann T, et al. Walk-ins seeking treatment at an emergency department or general practitioner out-of-hours service: a cross-sectional comparison. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:94 10.1186/1472-6963-11-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buja A, Toffanin R, Rigon S, et al. What determines frequent attendance at out-of-hours primary care services? Eur J Public Health 2015;25:563–8. 10.1093/eurpub/cku235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 2001;40:471–99. 10.1348/014466601164939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagai S. Predictors of help-seeking behavior: distinction between help-seeking intentions and help-seeking behavior. Jpn Psychol Res 2015;57:313–22. 10.1111/jpr.12091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hansen EH, Hunskaar S. Telephone triage by nurses in primary care out-of-hours services in Norway: an evaluation study based on written case scenarios. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:390–6. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.040824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giesen MJ, Keizer E, van de Pol J, et al. The impact of demand management strategies on parents’ decision-making for out-of-hours primary care: findings from a survey in The Netherlands. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014605 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019295supp001.pdf (283KB, pdf)