Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of a sport-specific energy availability (EA) questionnaire, combined with clinical interview, for identifying male athletes at risk of developing bone health, endocrine and performance consequences of relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S).

Methods

Fifty competitive male road cyclists, recruited through links of participants in a pilot study, were assessed by a newly developed sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview (SEAQ-I) and received dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) bone mineral density (BMD) and body composition scans and blood tests for endocrine markers.

Results

Low EA as assessed using the SEAQ-I, was observed in 28% of cyclists. Low lumbar spine BMD (Z-score<−1.0) was found in 44% of cyclists. EA was the most significant determinant of lumbar spine BMD Z-score (p<0.001). Among low EA cyclists, lack of previous load-bearing sport was associated with the lowest BMD (p=0.013). Low EA was associated with reduced total percentage fat (p<0.019). The 10 cyclists with chronic low EA had lower levels of testosterone compared with those having adequate EA (p=0.024). Mean vitamin D concentration was below the level recommended for athletes (90 nmol/L). Training loads were positively associated with power-to-weight ratios, assessed as 60 min functional threshold power (FTP) per kg (p<0.001). Percentage body fat was not significantly linked to cycling performance.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a SEAQ-I is effective for identifying male road cyclists with acute intermittent and chronic sustained low EA. Cyclists with low EA, particularly in the long-term, displayed adverse quantifiable measures of bone, endocrinology and performance consequences of RED-S.

Keywords: energy availability, male athletes, bone health, relative energy deficiency in sport

What are the key new findings of this study?

This is the first large study of male road cyclists to identify the major determinants of bone mineral density at a site known to be adversely impacted by relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S).

A sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview was effective at identifying male cyclists with both acute intermittent and chronic sustained low energy availability (EA).

Male cyclists identified as having low EA, particularly in the long-term, were demonstrated to have quantifiable effects on bone and endocrine health and cycling performance.

How might this study impact clinical practice in the future?

Athletes at risk of RED-S, including male athletes, should be assessed for low EA to prevent adverse health and performance sequelae.

A sport-specific questionnaire combined with sport-specific clinical interview may provide an effective and practical clinical tool to identify athletes/dancers at risk of RED-S.

Male cyclists would benefit from educational support for nutritional strategies and targeted off bike osteogenic exercise to prevent development of the clinical consequences of RED-S.

This study demonstrates the need for the educational on line resource on RED-S currently being developed for athletes, coaches, parents and healthcare professionals.

Introduction

Relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S), as described by the International Olympic Committee1 (IOC), refers to insufficient energy availability (EA) in both male and female athletes that can lead to detrimental sequelae on multiple body systems and athletic performance. Intentional energy deficit can arise from reducing body weight, to confer a performance advantage.2 Reduced EA can also arise inadvertently from high volumes of exercise accompanied by insufficient fuelling. Low EA is well described in female long distance runners.3–5 Yet there is a dearth of studies in male athletes,1 and consideration of sport-specific factors.6

As highlighted in the IOC update on RED-S,6 early identification of low EA in athletes is crucial to prevent development of adverse health and performance outcomes. However, identifying athletes at risk of RED-S continues to present a challenge in clinical practice. In research settings, calculation of a value for EA is laborious, valid only at the time of assessment and prone to inaccuracies. Moreover, in female athletes, an absolute threshold value of EA fails to determine menstrual function7 and no research in male athletes has investigated the magnitude and duration of low EA resulting in the clinical manifestations of RED-S.6

Although there are many potential consequences of low EA, quantification of bone mineral density (BMD) is an established, objective and clinically relevant indicator of long-term low EA. Low BMD is well documented in cross-sectional studies of male and female endurance athletes with low EA.8 9 The clinical consequence of BMD Z-score less than −1 is an increased injury risk.1 Nevertheless, widespread bone densitometry of athletes is not a feasible screening tool for RED-S.

In female athletes, validated questionnaires, such as LEAF-Q,10 are tools for screening for the female athlete triad. This questionnaire approach to identifying low EA has been shown to correlate with self-reported health and performance consequences of RED-S in female athletes.11 To date, no such questionnaire approach, combined with clinical interview to assess low EA, as recommended by the IOC6, has been applied to male athletes and correlated to quantified, objective health and performance outcomes of RED-S. Nor has any such screening tool been tailored for specific sports or to explore the sports-specific temporal aspects of low EA.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a sport-specific EA questionnaire and clinical interview (SEAQ-I) for identifying male cyclists at risk of developing consequences of RED-S.

Materials and methods

Participants

Male competitive road cyclists aged over 18 years were eligible to participate, if competing for at least 12 months at a level equivalent of British Cycling (BC) category 2 or above. Exclusion criteria included use of prescribed medications that could affect bone metabolism (not sports supplements) and diagnosed conditions that could affect nutrient absorption. No riders were excluded on these grounds. Data collection took place early in the cycle race season, during the months of March and April.

Sport-specific energy availability questionnaire and interview (SEAQ-I)

A questionnaire (online supplementary file 1) was developed specifically for male road cyclists covering details of years of cycle training, average weekly training hours and off-bike exercise. Nutritional information covered details of intentional weight loss, number of fasted rides per week, fuelling for rides over 1 hour, post-training recovery nutrition and use of supplements. Medical history recorded past injuries, including clinically diagnosed fracture (type and site), regular medications and family history of osteoporosis. The questionnaire was trialled in a pilot study and reviewed by a clinical sports endocrinologist, a sports research scientist, a registered sports performance dietician, competitive male cyclists and coaches for validation of content.

bmjsem-2018-000424supp001.pdf (41.2KB, pdf)

Following recommendations in the IOC consensus statements, an experienced clinician (Sports Endocrinologist) interviewed cyclists individually to verify and gather more detail on the responses provided in the questionnaire, in order to make a clinical evaluation of EA according to the following:

Chronic low EA: disordered eating requiring intervention from a sports performance dietician, or a diagnosed eating disorder, or intentional restrictive nutrition to achieve substantial weight loss (>7%) within 5 weeks and sustained over more than a cycle season (>12 months).

Acute intermittent low EA: limited fuelling around training (eg, weekly fasted rides), on a background of non-restrictive nutrition and small variations of body weight (<5%) during a cycle season.

Adequate EA: no restrictive nutrition practices and steady weight.

The SEAQ-I was undertaken to establish EA status before dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning.

Sport-specific performance metrics

In road cycling, a high power-to-weight ratio, expressed as 60 min functional threshold power (FTP) watts/kg confers a performance advantage. Cyclists quantify FTP according to BC protocol (or equivalent), typically early in the cycle season to set their training zones. This self-reported metric was recorded in the sport specific questionnaire, together with BC race category (which can be verified on the BC website).

Bone health parameters

Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using calibrated electronic scales (SECA Alpha, Birmingham, UK) and standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (SECA Alpha, Birmingham, UK) with head in Frankfurt plane. Bone health and body composition were evaluated using DXA (GE Lunar iDXA, GE Healthcare, UK), with cyclists in a rested state (refrained from intensive exercise, alcohol, caffeine and large food intake in the preceding 12 hours) and according to best practice recommendations for densitometry in athletes.12 BMD was evaluated at the anterior-posterior lumbar spine (L1–L4) and femoral neck. Age-matched BMD Z-scores were derived for each cyclist, at each skeletal site by the DXA software, using UK reference population data. In line with best practice, for the lumbar spine scans, when there was more than 1 SD difference between adjacent vertebrae (eg, with vertebral compression due to impaired bone health), the elevated vertebra was excluded from the analysis. Precision estimates (coefficient of variation) are 0.4% for lumbar spine BMD and 0.9% for femoral neck BMD.13 Body composition was derived from a total-body scan. Precision estimates for the body composition measures range from 0.5% to 0.9%.14

Endocrine health parameters

Endocrine and metabolic markers were assessed from capillary blood samples taken in the morning after waking. Samples were analysed to determine concentrations of total testosterone, vitamin D (25 OH), free triiodothyronine (T3), albumin, calcium, corrected calcium and alkaline phosphatase. The samples were analysed at Surrey University accredited laboratories using cobas8000 analyser with interassay coefficient of variation from <2% to 7% for the markers above. Absolute mean values with SD were determined. Blood results were expressed as Z-scores, using population mean and SD derived from the definition of the reference range, as covering 95% of a normal distribution.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using open source packages Orange15 (Bioinformatics Lab at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia) and SciPy (Enthought, Austin, Texas, USA). The data set included categorical and continuous observations, taken from the SEAQ-I, blood markers and DXA results. The means and SD of continuous variables were evaluated and, where relevant, compared against appropriate population reference ranges.

Explanatory analyses identified attributes associated with target variables relating to bone health and to cycling performance. Given that low BMD is an established marker of RED-S, the Z-score of the lowest BMD site was the target variable for bone health. BMD at other sites was excluded as an explanatory variable. The target variable for cycling performance was 60 min FTP per kg.

The equivalence of the means of subgroups distinguished by a binary variable, such as low EA, was evaluated using a two-sample t-test. The significance of the regression coefficients between continuous variables was based on the t-statistic. The robustness of results was tested using repeated data sampling.

Results

In the 50 cyclists, 4 cyclists were currently performing internationally, 20 nationally and the remainder regionally. The descriptive results for all cyclists are given in table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics

| N=50 | Mean±SD | Range (min–max) |

| Age (years) | 35.0±14.2 | 18–71 |

| Height (m) | 1.81±0.06 | 1.69–1.90 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.3±6.7 | 61.5–87.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.6±1.5 | 18.3–25.9 |

| Years of cycling training | 11.2±9.2 | 1.5–40.0 |

| Training load: average hours on bike/week | 12.5±4.4 | 6.0–24.0 |

| 60 min functional threshold power (W) | 329±46 | 195–416 |

| Average number of portions dairy/day | 2.4±1.4 | 0.0–5.0 |

| Average caffeine servings/day (coffee/gels, etc.) | 2.8±2.2 | 0.0–14.0 |

| Weekly alcohol units | 3.2±5.0 | 0.0–25.0 |

Low energy availability

From the SEAQ-I, 14 riders (28%) were identified as having low EA. Ten of these riders were assessed as having chronic low EA: five with diagnosed eating disorders or disordered eating and five described long-term intentional restrictive nutrition in terms of energy and food types such as carbohydrates (orthorexia) or in one rider adoption of veganism, in order to achieve a sustained low body weight. Four riders described intermittent short-term intentional energy restriction around training, undertaking more than one fasted ride per week, on a background of non-restrictive nutrition. All riders expressed strong views that achieving low body weight, in particular low body fat, was critical to maximising cycling performance in terms of watts per kilo. These views were reported as being based on discussion in cycling circles: cycling media, advice from coaches and practices in fellow cyclists.

Endocrine and metabolic biomarkers

Endocrine and metabolic biomarkers are given in table 2. Although 14 cyclists were taking specific vitamin D supplementation, mean vitamin D concentration was low for athletes. Even among those taking supplementation, some levels were still low. Mean concentration of testosterone fell in the lower end of the reference range. Mean free T3 concentration was in the lower half of the reference range.

Table 2.

Endocrine and metabolic biomarkers

| Mean±SD | Range (min–max) | |

| Albumin (35–52 g/L) |

43.5±3.0 | 37.3–50.6 |

| Albumin, Z-score |

−0.01±0.69 | −1.43 to 1.64 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (0–129 IU/L) |

65.0±24.7 | 32.0–161.0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, Z-score |

0.00±0.73 | −0.99 to 2.93 |

| Corrected calcium (2.21–2.52 mmol/L) |

2.41±0.14 | 1.97–2.90 |

| Corrected calcium, Z-score |

0.94±1.37 | −3.43 to 5.68 |

| Total testosterone (6/8–25/29 nmol/L) |

14.73±4.23 | 6.07–24.30 |

| Total testosterone, Z-score |

−0.67±0.88 | −2.45 to 1.34 |

| Free triiodothyronine (3.1–6.8 pmol/L) |

4.83±0.71 | 3.27 to 6.19 |

| Free triiodothyronine, Z-score |

−0.13±0.76 | −1.78 to 1.31 |

| Vitamin D 25 OH (50–175 nmol/L) |

74.8±33.4 | 31.1–167.0 |

| Vitamin D 25 OH, Z-score |

−1.19±1.06 | −2.55 to 1.71 |

Values in parentheses indicate relevant population reference ranges (age specific for testosterone).

Z-scores calculated from reference range (age specific in case of testosterone).

Bone health

BMD was lowest at the lumbar spine (table 3). Four cyclists showed more than 1SD difference between adjacent vertebrae (excluding these cyclists, had no significant impact on the results). All 30 reported fractures were traumatic from bike falls, including two cases of fractures in multiple vertebrae requiring internal fixation and bone graft. One stress fracture of the pelvis was sustained when a cyclist with previously undiagnosed osteoporosis started running (Z-score lumbar spine BMD −3.2).

Table 3.

BMD and body composition

| Mean±SD | Range (min–max) | |

| BMD | ||

| Lumbar spine L1-L4 BMD (g/cm2) | 1.108±0.152 | 0.807–1.409 |

| Lumbar spine Z-score | - 0.8±1.2 | −3.2 to 1.6 |

| Femoral neck mean BMD (g/cm2) | 0.974±0.119 | 0.707–1.218 |

| Femoral neck Z-score | - 0.6±0.9 | −2.6 to 1.0 |

| Body composition | ||

| Total fat mass (kg) | 10.01±2.42 | 4.75–14.25 |

| Fat mass Z-score | –1.1±0.9 | −3.2 to 0.7 |

| Body fat percentage | 14.1±3.2 | 7.5–20.1 |

| VAT (kg) | 0.222±0.147 | 0.000–0.744 |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 60.89±6.00 | 49.90–74.92 |

| Leg lean mass (kg) | 21.32±2.51 | 16.84–29.30 |

BMD, bone mineral density; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

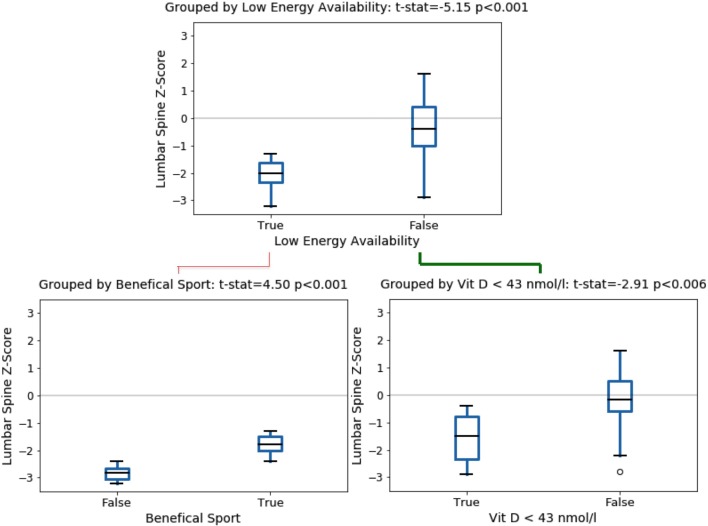

The full data set was explored to find variables associated with lumbar spine BMD. The most significant explanatory variable of low lumbar spine BMD was low EA as determined from the SEAQ-I (p<0.001), shown in the upper chart of figure 1. The 14 cyclists with low EA had a mean lumbar spine BMD Z-score of −2.0±0.6, this being significantly lower than in cyclists assessed as having adequate EA with mean Z-score −0.4±1.1.

Figure 1.

Boxplots showing male cyclist lumbar spine BMD Z-Score in subgroups. BMD, bone mineral density.

In cyclists with low EA (lower left in figure 1, n=14), previous participation in beneficial weight-bearing sport provided some attenuation of effect on lumbar spine BMD (p<0.001). In cyclists with adequate EA (lower right in figure 1, n=36), very low vitamin D (Z-score of - 2.2, equivalent to 43 nmol/L) was significantly related to low lumbar spine BMD (p<0.006). Figure 2 presents these results in the form of a Decision Tree.

Figure 2.

Decision tree showing key variables explaining lumbar spine BMD Z-score in male cyclists. BMD, bone mineral density; EA, energy availability.

Compared with cyclists maintaining adequate EA, those with low EA (n=14) were observed to have lower percentage body fat (12.4% vs 14.8%, p=0.019) and lower VAT mass (0.15 kg vs 0.25 kg, p=0.002). Cyclists with chronic low EA (n=10) had lower levels of testosterone (Z-score −1.26 vs −0.54, p=0.024) and lower body mass index (21.8 vs 22.8, p=0.018).

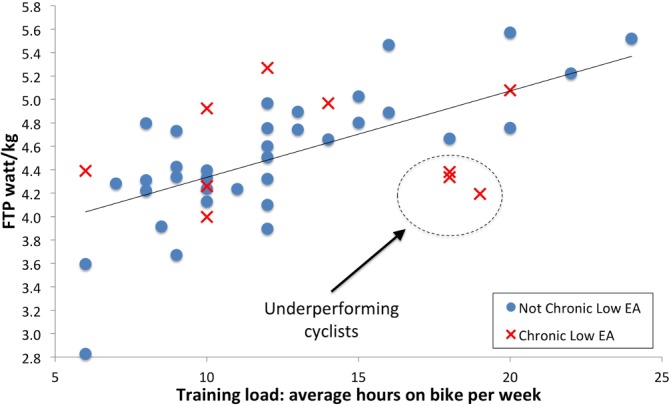

Determinants of cycling performance

Cycling performance defined as 60 min FTP watts/kg was confirmed as the important determinant of race performance with a strong relationship to BC race category (R2=0.39, p<0.001). Apart from age, weekly training load was the most important factor associated with FTP watts/kg (R2=0.39, p<0.001). Figure 3 shows a notable cluster of underperforming cyclists with most prolonged low EA and higher training loads, but not producing the power-to-weight ratio that would be anticipated for their training load. Follow-up and further studies may be able to establish the significance of this observation. There was a negative, but non-significant relationship between testosterone and weekly training load (R2=0.06, p<0.089). There was no significant association between percentage body fat and performance.

Figure 3.

FTP watts/kg vs weekly training hours. FTP, functional threshold power.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the effectiveness of a practical method to identify male athletes at risk of the potential health and performance consequences of RED-S. We demonstrate that a sport-specific screening questionnaire and clinical interview (SEAQ-I) is an effective clinical tool for identifying male cyclists with low EA. Low EA as assessed by SEAQ-I was the most significant explanatory variable of low BMD, which is an established objective and quantifiable clinical outcome of RED-S. Those cyclists with chronic low EA, also had reduced testosterone, lower body fat and impaired cycling performance at higher training loads.

SEAQ-I and RED-S bone health outcomes

Consistent with studies conducted in male cyclists elsewhere,16 17 negative BMD Z-scores were most marked at the lumbar spine, a site predominantly comprising trabecular rich bone and receiving little osteogenic force. Although mean femoral neck BMD Z-score was also negative, this appeared attenuated, potentially reflecting biomechanical forces to bone at this site from leg musculature and standing on the pedals, together with higher composition of cortical bone of a slower turnover rate.

The most significant factor explaining reduced lumbar spine BMD in our group of male cyclists was low EA, as assessed from SEAQ-I. This is in keeping with the aforementioned study of female athletes where low EA assessed through questionnaire was linked to self-reported bone health manifestations of RED-S.11

Within the low EA group, cyclists who had not undertaken previous load-bearing exercise during their youth, before cycling became their sole sport, had significantly lower lumbar spine BMD. This timing of combined low EA and low osteogenic stimulus could impair attainment of peak bone mass18 and optimisation of bone microarchitecture19 with potential irreversible effects on bone even once adequate EA and body weight is restored.20

The positive influence of current resistance training on the BMD of cyclists has been reported21 and targeted mechanical and muscular loading of the lumbar spine in rowers attenuates the negative impact of RED-S at this site.22 However, in the current study, no associations between current strength training and lumbar spine BMD were found, as any resistance training focused predominantly on leg muscle strength, not bone health.

The clinical consequence of impaired bone health in load-bearing sports is the increased risk of bone stress injuries. However, as cycling is weight-supported, these signs are absent and most fractures are traumatic from bike falls. Among professional cyclists, traumatic fractures are the most commonly reported injury, with vertebral fracture requiring the longest time off training.23

SEAQ-I and RED-S endocrine outcomes

In female athletes, menstrual disruption is an overt clinical sign of low EA. In male endurance runners, testosterone is proposed as an objective indicator of low EA and clinical outcome of bone stress injury.24 Even short term low EA, occurring within a day, reduces testosterone25 and bone turnover markers.26 Such acute energy deficits would occur during fasted rides. However, even in the situation of adequate EA, endurance training alone can reduce testosterone in male athletes,27 including male road cyclists.28 29 In the current study, mean testosterone concentration of these endurance cyclists fell in the lower end of the reference range. Furthermore, the combined effect of training and chronic low EA resulted in a significantly lower testosterone concentration, compared with those cyclists with adequate EA. Testosterone is required for bone mineralisation and has an inhibitory effect on bone resorption.30 Testosterone is also important for athletic performance via physiological actions31 which could provide an incentive for male athletes to address sustained low EA.

In cyclists with adequate EA, lower lumbar spine BMD was associated with lower concentrations of vitamin D (<43 nmol/L). Although after winter, vitamin D levels in the UK population are likely to be at the lowest, the low levels found in the cyclists are surprising given that this is an outdoor sport. Even those cyclists taking vitamin D supplementation did not uniformly have higher levels, reflecting variation in dose and consistency of supplementation being taken. The significance of these findings is that, in athletes, there is compelling evidence that being replete in vitamin D>90 nmol/L has benefits32 in terms of injury reduction,33 muscle function34 and immunity.35 In men, vitamin D is reported to exert a synergistic action on testosterone.36 37 Our findings suggest that male cyclists may be at risk for deficiencies in vitamin D and therefore benefit from testing and appropriate supplementation.

SEAQ-I and RED-S performance outcomes

Training is the most effective way to achieve physiological adaptations, shown by the significant positive relationship between training load and 60 min FTP watts/kg. However, as demonstrated in this study, high training loads, if not matched with sufficient nutritional intake, result in chronic low EA, which rather than supporting performance, hinders attainment of predicted performance. Yet, all the riders in this study, whose body fat was already low (mean Z-Score −1.1), described promotion of fat loss in cycling circles to improve performance. None of our top-performing cyclists was assessed by the SEAQ-I as having long-term low EA.

The rationale for fasted rides is to enhance adaptations. Periodised carbohydrate intake with strategic use of low carbohydrate availability for low intensity sessions is employed in top-level cycle teams.38 However, unlike amateur riders, professional cyclists benefit from careful monitoring by a multidisciplinary team. In this study, mean free T3 concentration, indicating short-term EA24 was in the lower half of the reference range. Superimposing acute low EA on riders already in chronic low EA could limit rather than support performance.

Limitations

FTP was self-reported, being the most practical method of assessing quantifiable cycling performance. Reported FTP was checked at interview and with BC race category for validity. To minimise diurnal variation, capillary venous bloods were taken in the morning, as close as possible to the scan day.

Conclusion

A sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview (SEAQ-I) was found to be effective in identifying competitive male road cyclists with acute intermittent and chronic sustained low EA. Cyclists evaluated as having low EA, particularly in the long-term, were found to have adverse quantifiable measures of bone, endocrine and performance consequences of RED-S.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the cyclists and coaches for their interest and participation in this study. Many thanks to Sophie Killer and Renne McGregor for comments on sports performance nutrition. Thanks to Jamie Francis for his input on cycling aspects in study design and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Ian Entwistle and Brian Oldroyd, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK.

Contributors: NK: conceptualisation of project, development of study design, research funding application, involvement of cyclists, their coaches and sports performance dieticians, conducting clinical sport specific interviews, drafting and revision of manuscript. GF: cycle specific advanced statistical analysis and revision of manuscript. KH: development of study design, research funding application, scanning of cyclists, drafting and revision of manuscript, IE and BO scanning of cyclists.

Funding: Thank you to the British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine (BASEM) for funding this study with a research bursary. Thanks also to SunVitD3 for funding the analysis of endocrine and metabolic markers.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Leeds Beckett University Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. . The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad--Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br J Sports Med 2014;48:491–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haakonssen EC, Martin DT, Jenkins DG, et al. . Race weight: perceptions of elite female road cyclists. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015;10:311–7. 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zanker C, Hind K. The effect of energy balance on endocrine function and bone health in youth. In Optimizing Bone Mass and Strength. Karger Publishers 2007:5181–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nieves JW, Melsop K, Curtis M, et al. . Nutritional factors that influence change in bone density and stress fracture risk among young female cross-country runners. Pm R 2010;2:740–50. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schnackenburg KE, Macdonald HM, Ferber R, et al. . Bone quality and muscle strength in female athletes with lower limb stress fractures. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:2110–9. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821f8634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM, et al. . IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:687–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lieberman JL, DE Souza MJ, Wagstaff DA, et al. . Menstrual disruption with exercise is not linked to an energy availability threshold. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2018;50:551–61. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hind K, Truscott JG, Evans JA. Low lumbar spine bone mineral density in both male and female endurance runners. Bone 2006;39:880–5. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Viner RT, Harris M, Berning JR, et al. . Energy availability and dietary patterns of adult male and female competitive cyclists with lower than expected bone mineral density. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2015;25:594–602. 10.1123/ijsnem.2015-0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melin A, Tornberg AB, Skouby S, et al. . The LEAF questionnaire: a screening tool for the identification of female athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:540–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ackerman KE, Holtzman B, Cooper KM, et al. . Low energy availability surrogates correlate with health and performance consequences of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport. Br J Sports Med 2018;0 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hind K, Slater G, Oldroyd B, et al. . Interpretation of Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry-Derived Body Composition Change in Athletes: A Review and Recommendations for Best Practice. J Clin Densitom 2018;21:429–43. 10.1016/j.jocd.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hind K, Oldroyd B, Truscott JG. In vivo precision of the GE Lunar iDXA densitometer for the measurement of total-body, lumbar spine, and femoral bone mineral density in adults. J Clin Densitom 2010;13:413–7. 10.1016/j.jocd.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harley JA, Hind K, O’hara JP, O’Hara J. Three-compartment body composition changes in elite rugby league players during a super league season, measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:1024–9. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cc21fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Demsar J, Curk T, Erjavec A, Orange. Data mining toolbox in python. JMLR 2013;14:2349–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smathers AM, Bemben MG, Bemben DA. Bone density comparisons in male competitive road cyclists and untrained controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:290–6. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318185493e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rector RS, Rogers R, Ruebel M, et al. . Participation in road cycling vs running is associated with lower bone mineral density in men. Metabolism 2008;57:226–32. 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keay N, Frost M, Blake G. Study of the factors influencing the accumulation of bone mineral density in girls. Osteoporosis International 2000;11(Suppl 1):S31. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vlachopoulos D, Barker AR, Ubago-Guisado E, et al. . Longitudinal adaptations of bone mass, geometry, and metabolism in adolescent male athletes: the PRO-BONE study. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:2269-2277 10.1002/jbmr.3206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keay N, Fogelman I, Blake G. Bone mineral density in professional female dancers. Br J Sports Med 1997;31:143–7. 10.1136/bjsm.31.2.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mathis SL, Caputo JL. Resistance training is associated with higher lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density in competitive male cyclists. J Strength Cond Res 2018;32:274–9. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wolman RL, Clark P, McNally E, et al. . Menstrual state and exercise as determinants of spinal trabecular bone density in female athletes. BMJ 1990;301:516–8. 10.1136/bmj.301.6751.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. If you think something is broken, report a problem, 2018. Looks like something went wrong when processing your request. Available from: www.procyclingstats.com/statistics/rider-injuries [accessed May 2018].

- 24. Heikura IA, Uusitalo ALT, Stellingwerff T, et al. . Low energy availability s difficult to assess but outcomes have large impact on bone injury rates in elite distance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018;28:403–11. 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torstveit MK, Fahrenholtz I, Stenqvist TB, et al. . Within-day energy deficiency and metabolic perturbation in male endurance athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018;28:419–27. 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Townsend R, Elliott-Sale KJ, Currell K, et al. . The effect of postexercise carbohydrate and protein ingestion on bone metabolism. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017;49:129–37. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hooper DR, Tenforde AS, Hackney AC. Treating exercise-associated low testosterone and its related symptoms. Phys Sportsmed 2018;27:1–8. 10.1080/00913847.2018.1507234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fernández-Garcia B, Lucía A, Hoyos J, et al. . The response of sexual and stress hormones of male pro-cyclists during continuous intense competition. Int J Sports Med 2002;23:555–60. 10.1055/s-2002-35532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lucía A, Díaz B, Hoyos J, et al. . Hormone levels of world class cyclists during the Tour of Spain stage race. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:424–30. 10.1136/bjsm.35.6.424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michael H, Härkönen PL, Väänänen HK, et al. . Estrogen and testosterone use different cellular pathways to inhibit osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:2224–32. 10.1359/JBMR.050803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Storer TW. Proof of the effect of testosterone on skeletal muscle. J Endocrinol 2001;170:27–38. 10.1677/joe.0.1700027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Owens DJ, Allison R, Close GL. Vitamin D and the Athlete: current perspectives and new challenges. Sports Med 2018;48(Suppl 1):3–16. 10.1007/s40279-017-0841-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lappe J, Cullen D, Haynatzki G, et al. . Calcium and vitamin d supplementation decreases incidence of stress fractures in female navy recruits. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:741–9. 10.1359/jbmr.080102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wyon MA, Koutedakis Y, Wolman R, et al. . The influence of winter vitamin D supplementation on muscle function and injury occurrence in elite ballet dancers: a controlled study. J Sci Med Sport 2014;17:8–12. 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He CS, Handzlik M, Fraser WD, et al. . Influence of vitamin D status on respiratory infection incidence and immune function during 4 months of winter training in endurance sport athletes. Exerc Immunol Rev 2013;19:86–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pilz S, Frisch S, Koertke H, et al. . Effect of vitamin D supplementation on testosterone levels in men. Horm Metab Res 2011;43:223–5. 10.1055/s-0030-1269854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blomberg Jensen M, Jensen MB. Vitamin D metabolism, sex hormones, and male reproductive function. Reproduction 2012;144:135–52. 10.1530/REP-12-0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Impey SG, Hearris MA, Hammond KM, et al. . Fuel for the work required: a theoretical framework for carbohydrate periodization and the glycogen threshold hypothesis. Sports Med 2018;48:1031–48. 10.1007/s40279-018-0867-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2018-000424supp001.pdf (41.2KB, pdf)