Abstract

We report a child with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome with an increase in seizure frequency and loss of psychomotor skills due to a disintegrated cervical VNS lead, not detected during standard device monitoring. The lead was completely removed and replaced by a new 303 lead on the same nerve segment. After reinitiating VNS, side effects forced us to switch it off, resulting in immediate seizure recurrence. EEG recording demonstrated a non-convulsive status epilepticus that was halted by reinitiating VNS therapy. Thereafter, he remained seizure free for eight months, and regained psychomotor development.

Keywords: Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, Refractory epilepsy, Revision surgery, Seizure freedom, Vagus nerve stimulation

Highlights

-

•

Routine VNS device monitoring may not always detect lead dysfunction.

-

•

Seizure recurrence and loss of psychomotor skills may imply lead dysfunction.

-

•

Complete VNS revision may yield excellent results in LGS.

-

•

VNS revision can correct clinical deterioration associated with lead dysfunction.

1. Introduction

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is one of the most challenging epilepsies to manage, due to a range of different seizure types which are frequently refractory to anti-seizure drug treatment. In patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, treatment options other than anti-seizure drugs are often considered; including epilepsy surgery, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy and a ketogenic diet.

We report a case of a boy with LGS and drug-resistant epilepsy responding to VNS therapy that is remarkable in several ways.

2. Case study

A now 16-year-old boy with a LGS, associated with an ARGHAP35 gene mutation, reached all developmental milestones until the age of 13 months. Then he had his first cluster of seizures. Seizures consisted of 6–7 tonic seizures and numerous atonic seizures and myoclonia daily, and soon became drug resistant. His developmental status rapidly deteriorated to a severe psychomotor retardation. His EEG demonstrated an epileptic encephalopathy with multifocal high amplitude spike and wave discharges. Brain MRI, MRS, EMG, VEP, as well as neurometabolic and genetic analysis were unremarkable at that time. He was previously treated with multiple anti-seizure drugs (phenobarbital, pyridoxine, valproate, nitrazepam, clobazam, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, levetiracetam, topiramate, ethosuximide), and additionally the ketogenic diet, all without any significant effect. At the age of five years a VNS system (generator type 102, lead type 302, Cyberonics (now LivaNova), Houston, USA) was implanted. Hereafter, he was more alert, his seizure frequency decreased, and he started to regain developmental milestones. Fifteen months later, seizure frequency increased and his psychomotor skills again deteriorated. When controlling the stimulator parameters, a high DC code (of 7) was measured. This suggested a high impedance either due to perineural gliosis at the electrode–vagus nerve interface or due to lead breakage. A disconnection between lead and generator was identified and surgically repaired. During this procedure, the VNS generator (2 years old) was replaced prophylactically. Intraoperative device testing was uneventful. He did well for several months, but then seizure frequency again increased, with loss of alertness and developmental arrest. EEG was consistent with a severe epileptic encephalopathy with slow spike-and-waves, compatible with LGS. Optimizing the VNS parameters (output current 1.75 mA, frequency 30 Hz, pulse duration 500 μs, signal on time 30 s, signal off time 1.8 min) had no beneficial effect. As the VNS system was controlled several times a year, always without any indication of a technical failure, we assumed VNS was no longer as effective as it used to be in this particular patient. Treatment with rufinamide (Inovelon®) slightly decreased his seizure frequency to 3–4 tonic seizures a day, always accompanied by an increase in heartrate. Because of this ictal tachycardia, we decided to implant the new 106 generator (AspireSR, Cyberonics, Houston, USA), with his next scheduled generator replacement at the age of almost 16 years.

During this surgery, unexpectedly, the entire VNS system had to be replaced because the silicone lead insulation had apparently completely disintegrated over the years (10 years after primary implantation), a well-known complication after prolonged VNS therapy using the older type 302 lead [1]. After surgery, the generator was set to a lower output current (0.625 mA, 30 Hz, 500 μs, 30 s on/1.8 min off) to prevent sudden overstimulation of an irritated vagus nerve, while skipping the usual two-week stimulation-free interval after (initial) lead implantation. Despite the lower output current, he suffered from frequent vomiting. First, we decreased output current to a very low setting of 0.25 mA, but ultimately we had to switch off VNS 8 days after surgery assuming the vagus nerve was still irritated as other causes for vomiting had been excluded by tapering down anti-seizure drugs, checking relevant blood values, an EEG, and a brain CT scan. Interestingly, switching off the VNS resulted in seizure recurrence within 1 h, followed three days later by a non-convulsive status epilepticus which was refractory to intravenous midazolam and phenytoin treatment (Fig. 1A). Turning on the VNS (still with an output current of just 0.25 mA) immediately resulted in cessation of the status epilepticus (Fig. 1B), confirmed by EEG recording and repeat EEG recording the next day. Eventually, persisting vomiting proved to be the result of constipation and resolved with laxative therapy. Since VNS re-initiation, he remained seizure free for 8 consecutive months. Four months after VNS re-initiation, his EEG demonstrates considerable improvement, i.e. no seizures during 24 h of recording, no interictal discharges during wakefulness (previously in 85–100% of time) and a significant decrease in interictal epileptiform discharges during sleep, with only mild sleep pattern disturbances. No other factors could be identified to explain the improvement. We did not change or add any anti-seizure medication or started other therapies. He has again shown progressive psychomotor development. Moreover, for the first time in his 16-year life, he is now alert and actively discovers his environment, he uses his own voice, he grabs, throws and plays with toys, and he has started to walk and even understand simple instructions, clearly a completely new situation for his parents and caregivers.

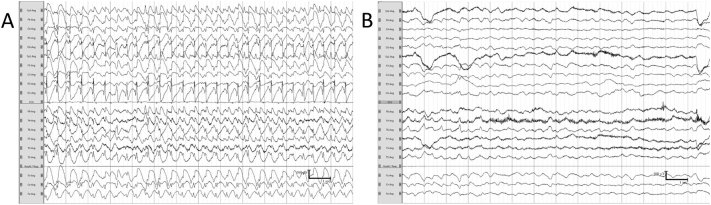

Fig. 1.

(A–B): Two 14-s fragments of the patients' electroencephalograms showing the patterns before and after activation of the VNS.

Fragment (A) shows an electroencephalographic-pattern status epilepticus. Fragment (B) is from the patients' electroencephalogram after VNS activation showing marked slowing of background activity and few epileptiform discharges in the right temporal region.

3. Discussion

This case of LGS responding to VNS therapy is remarkable in several ways. First, complete disintegration of the 302 lead insulation was not detected during system check, including the standard device monitoring, impedance test, magnet use, and for unknown reasons the impedance was always within normal limits. Neither the authors nor the vendor (LivaNova) has been able to identify why this dysfunction was not diagnosed during these checks. Second, this case illustrates one should be very cautious to switch off VNS abruptly, because this can promptly result in seizures and even in (non-convulsive) status epilepticus. Third, while his non-convulsive status epilepticus was refractory to drug therapy, it was immediately halted by re-initiating VNS therapy. Although the effectiveness of VNS therapy for the cessation of refractory status epilepticus has been previously reported [2], the almost instantaneous seizure reoccurrence followed by a non-convulsive status epilepticus after VNS switch-off, and the rapid cessation of status epilepticus with VNS switch-on were striking. Fourth, this case highlights the importance to consider VNS therapy in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Even in patients with LGS, known to have a poor prognosis with regard to seizure outcome, seizure freedom may rarely be achieved by VNS therapy. Seizure freedom in LGS has been reported after a period of three years of VNS therapy [3], but not so promptly after turning on a (completely replaced) VNS system as in our patient. The LivaNova 302 electrode has a silicone coating which – like all silicone coatings – is subject to degradation over time. The clinical effects of degradation depend on the site and extent and may range from local effects at the site of most pronounced degradation, e.g. pain, hoarseness, to complete failure marked by an increase in seizure frequency. Lead dysfunction has created a need for revision surgery; this type of surgery is complex owing to position of the leads near major vasculature, scar tissue obscuring the electrode–nerve complex and ongoing debate on subtotal versus total removal [1]. Indications for removal include radiologically confirmed breakage of leads as well as indirect signs, including high impedance. Finally, this case illustrates that complete VNS revision (lead removal and subsequent replacement) if performed correctly may yield excellent results without clinically relevant side effects even in the most challenging cases.

4. Conclusion

VNS therapy in our patient was associated with cessation of status epilepticus, seizure freedom, and restored psychomotor function. System assessment during programming the VNS may not always detect lead dysfunction which should therefore be considered if seizure recurrence and loss of psychomotor skills occur in previously effective VNS therapy without any alternative explanation. In our case of LGS with 8 months of follow-up, we found that complete VNS revision (lead removal and subsequent replacement) if performed in patients using newer models sensing heart rate correctly may yield excellent results without clinically relevant side effects.

Acknowledgments

Funding

No external funding was obtained for this study.

Conflict of interest

E. Cornips has a consultancy agreement with LivaNova, the company that produces the VNS hardware. The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. No funding was obtained.

We confirm that we have read the Journals' position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Ethical statement

We ensure that the work described has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). We have included a statement in the manuscript that informed consent was obtained from the patients' parents.

Contributor Information

Hilde M. Braakman, Email: braakmanh@kempenhaeghe.nl.

Joke Creemers, Email: creemersj@kempenhaeghe.nl.

Danny M. Hilkman, Email: dmw.hilkman@mumc.nl.

Sylvia Klinkenberg, Email: s.klinkenberg@mumc.nl.

Suzanne M. Koudijs, Email: suzanne.koudijs@mumc.nl.

Mariette Debeij-van Hall, Email: debeij-vanhallm@kempenhaeghe.nl.

Erwin M. Cornips, Email: e.cornips@mumc.nl.

References

- 1.Aalbers M.W., Rijkers K., Klinkenberg S., Majoie M., Cornips E.M. Vagus nerve stimulation lead removal or replacement: surgical technique, institutional experience, and literature overview. Acta Neurochir. 2015;157:1917–1924. doi: 10.1007/s00701-015-2547-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Herdt V., Waterschoot L., Vonck K., Dermaut B., Verhelst H., Van Coster R. Vagus nerve stimulation for refractory status epilepticus. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13:286–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buoni S., Zannolli R., Macucci F., Pieri S., Galluzzi P., Mariottini A. Delayed response of seizures with vagus nerve stimulation in Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Neurology. 2004;63:1539–1540. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141854.58301.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]