Abstract

We present a 29-year-old woman who was treated for a giant-cell tumour of her thumb. Surgical treatment was performed in two stages. In the first stage, the tumour was removed and the first metacarpal and distal phalanges were fixed by an external fixator. In the second stage of reconstruction of the thumb, a cortico-cancellous bone graft from the iliac crest, an external fixator and double arthrodesis were used. This two-stage procedure provides the possibility for confirming the diagnosis and appropriate treatment choice and minimizes the risk of recurrence.

Keywords: Bone tumours, Giant cell tumour, Thumb

Introduction

Giant cell tumour (GCT) in bone is usually located in the ends of the long bone, accounting for approximately for 5% of primary bone tumour. Only 2–5% of GCTs are located in the hand.1, 2, 3 In the hand region, GCTs are primarily located in the metacarpal bones; second, they are located in the phalanges and, rarely, they are located within the thumb. As Yanagisawa3 reported, the location of the hand is associated with a young age that typically ranges from 20 to 30 years. We will present the diagnostic and therapeutic process for GCT of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. The treatment was performed with the following two surgical procedures: surgical resection of the tumour and reconstruction of the thumb with a cortico-cancellous bone graft, external fixator and double arthrodesis.

Patient and methods

A 29-year-old woman presented with swelling at the base of the thumb of dominant left hand. The patient had first observed symptoms 4 weeks before medical examination. The patient reported no prior injuries and no history of disease or other comorbidities. She gave birth to a daughter 4 months prior. She had no pain at rest, only swelling, and no redness. The range of motion at the metacarpophalangeal joint (MP) as well as at the interphalangeal joint (IP) was limited by pain and swelling. There was no disturbance in her sensation or blood supply. Radiologic evaluation showed a large, irregular, expansive lesion in the proximal phalanx of the left thumb (Fig. 1). The tumour was classified as second stage according to the Campanacci Radiological Grading System. MRI scans showed the tumour had a fairly homogeneous, intermediate signal on T1-weighted images. T2-weighted images demonstrated a hyperintense lesion of the entire proximal phalanx of the thumb (Fig. 2). The scintigraphy survey did not show neoplastic changes in other places. It revealed a significant increase in uptake within the affected tissue. Radiography and MRI supported a diagnosis of GCT. Due to the extent of the changes, suspicion of malignancy and risk of metastasis, we not use a fine needle aspiration biopsy; instead, we used as a basic standard in the case of suspected GCT in a typical location around the knee.

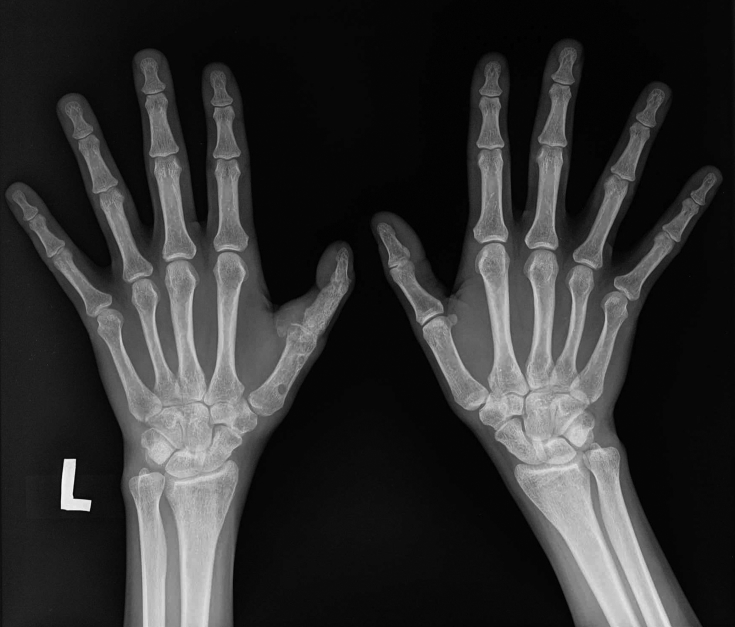

Fig. 1.

Preoperative posterior - anterior x-ray both hands demonstrating the expansive lytic lesion of the proximal phalanx of the thumb.

Fig. 2.

T2 weighted coronal MRI demonstrating a hyperintense lesion of the whole proximal phalanx of the thumb.

The surgery began with placement of the external fixator. The procedure was performed using the dorsal approach. The procedure involved unveiling of the distal part of the first metacarpal bone, proximal phalanx and base of the distal phalanx. The proximal phalanx was changed and expanded along the entire length. The tumour was fully excised. In the cross-section, there was a non-uniform structure with necrosis and dissolution characteristics in the central portion. The articular cartilage, from the distal first metacarpal bone and proximal portion of the distal phalanx, was removed. The procedure revealed normal, intact bone structure. We removed the bone's fragment, and the bone sample from the exposed first metacarpal bone and distal phalanx was sent for histopathological examination (to ascertain that the tumour was radically removed with a safety margin).

The immobilization was performed using an external fixator with two pins in the first metacarpal bone and one pin in the distal phalanx. The histopathological results revealed a GCT (Fig. 3), confirmed radical excision and ruled out the presence of tumour residue. After 2 weeks, the second operation was performed. Old scar tissue was removed, and the bone was decorticated. The external fixator was applied with small distraction; then, between the 1st metacarpal and distal phalanx, the cortico-canceolous bone graft from the iliac crest was inserted. The bone autograft was fixed using two Kirschner's wires (Fig. 4). The thumb was positioned in opposition and double arthrodesis was created. After 4 weeks, bone union was achieved and the external fixation was removed according to the procedure.

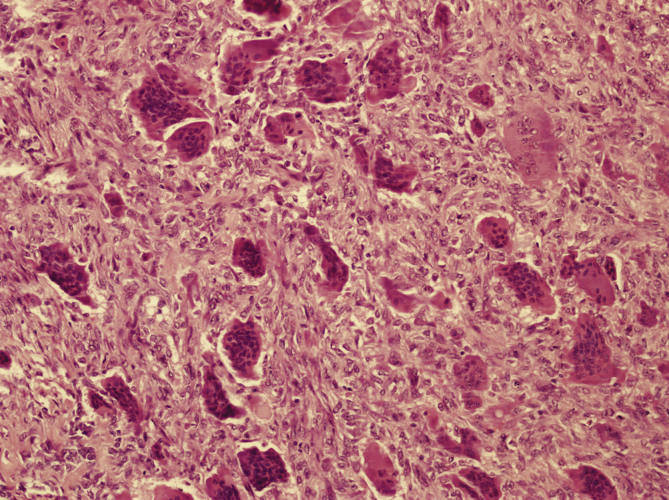

Fig. 3.

Histologic appearance of a giant cell tumor (magnification 200, haematoxylin-eozin staining). Histologic specimen of the giant cell lesion.

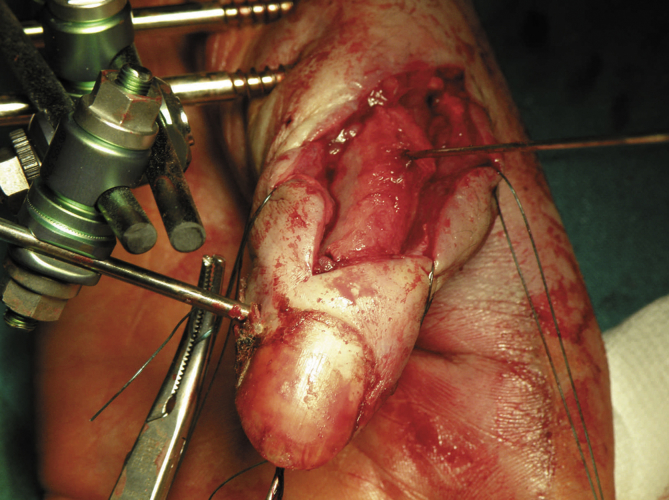

Fig. 4.

Intraoperatitely picture, showing stabilization bone graft by K wire.

Results

At the 24-month follow up examination, the patient had no evidence of giant-cell tumour and had no range of motion in the MP and IP, but she had strong bone union (Fig. 5). The thumb was in opposition, allowing the patient to perform activities of daily living (Fig. 6). The DASH score was 9.5, and the VAS score was 1. There was no tenderness on palpation, and the touch and discriminatory sensations were comparable with the other hand.

Fig. 5.

Postoperative X ray 24 months after operation, demonstrating bone union and bone remodelling.

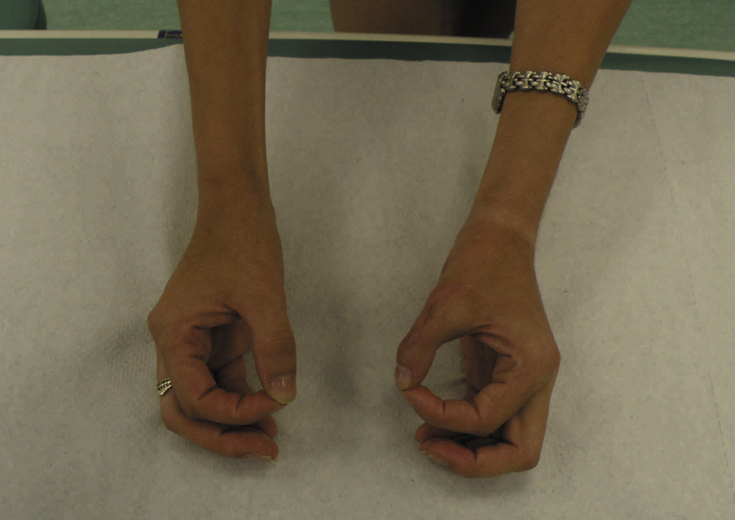

Fig. 6.

The outcome 24 months after surgery.

Discussion

GCT was originally thought to be a type of osteosarcoma. Some authors have reported that the diagnosis could be made by excluding other possibilities. The radiologic differential diagnosis for such lesion includes aneurysmal bone cysts, benign chondroblastoma, non-osteogenic fibroma, simple bone cyst, and, in some cases, osteosarcoma, brown tumour of hyperparathyroidism, enchondroma, metastatic disease, chondrosarcoma, and giant cell reparative granuloma.4 GCT in the hand is well characterised and has a higher risk of malignancy, recurrence and metastatic disease. In this case, retaining function of the thumb with sufficiently aggressive surgical treatment is extremely difficult.5 The treatment of GCT using intraregional procedures includes the following: curettage and bone grafting or excisional procedures, such as local excision, wide excision, amputation, and ray resection.1 Intralesional curettage may be improved with local adjuvant treatment, such as phenol,6, 7 alcohol,8, 9 and cryotherapy.10, 11 Bone defects can be supplemented with polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, autograft, allograft or bone substitute.12 In addition, treatment can be enhanced with the use of monoclonal antibody,13 calcitonin,14 and bisphosphonates.15 However, it should be noted that the effectiveness of these methods in the treatment and prevention of recurrence is still under discussion and there is no gold standard for treating GCT.16

Procedures such as curettage and bone grafting do not give satisfactory results and may contribute to recurrence. Due to the high percentage of recurrence, some authors do not recommend curettage alone.1, 2 Averill et al reported success in more than 70% of recurrent lesions that were treated with wide excision or amputation.2 On the other hand, an amputation or ray resection is associated with loss of motor function and various degrees of injury to the patient. Due to the lack of satisfactory outcomes, a number of authors are trying to determine the risk factors that affect the number of relapses.17, 18 Dickson et al reported on the expression of p63 immunostaining in the mononuclear cells of giant cell tumours.17 This examination is useful for distinguishing between giant cell tumour and other giant cell-rich tumours, such as aneurysmal bone cysts, chondroblastoma, and reparative giant cell granuloma. On the other hand, Williams showed no significance for gender, age, hand dominance or radiologic findings.18 The statistical analysis showed significant differences between specific tissue or expires and recurrence. Positive correlation was noted for involvement of the extensor tendon, flexor tendon, and join capsule.

Evaluation of the treatment outcomes was confounded by the fact that although most recurrences occur within 3 years of treatment, late recurrence of giant cell tumours, even after 15 years later, have been observed in the location where identified lesion had been surgically managed19; others were observed to recur as late as 42 years later.20

One reason for the high number of recurrences is insufficient removal of radical changes during curettage. When using curettage, we cannot assess whether the tumour has been fully removed. Moreover, any recurrence that is combined with involvement of another bone region, as in the case of the thumb, restricts the subsequent procedure options. The histopathological confirmation of a safely excised margin offers the best chance for avoiding recurrence. An additional advantage of a two-stage treatment is avoidance of an incorrect diagnosis because the results do not always coincide with the biopsy results. Additionally, in the event of misdiagnosis, this approach allows for the use of different treatment techniques. In our case, because of the extent of the changes, there was no opportunity for using curettage and a bone graft (distended, thin cortical). On the other hand, we are aware that a disadvantage of such a procedure is the need to perform two operations and maintain immobilization.

In our opinion, misdiagnosis and resection of the tumour with too small of a safety margin contributes to recurrence and requires changing the procedure to a more invasive technique. The histopathological confirmation of diagnosis and radical removal of the tumour increase the probability that there will not be any recurrence.

Conclusion

The two-stage surgical procedures provide the possibility to confirm the diagnosis and eliminate incorrect diagnosis. Furthermore, they offer a confirmation for applying the radical method. Overall, this technique minimizes the risk of recurrence.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Turkish Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology.

References

- 1.Athanasian E.A., Wold L.E., Amadio P.C. Giant cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg. 1997;22A:91–98. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80187-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averill R.M., Smith R.J., Campbell C.J. Giant-cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg. 1980;5A:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagisawa M., Okada K., Tajino T., Torigoe T., Kawai A., Nishida J. A clinicopathological study of giant cell tumor of small bones. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:265–268. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2011.596290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlin D.C. Giant cell tumor of bone: high lights of 407 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:955–960. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.5.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fnini S., Labsaili N., Messoudi A., Largab A. Giant cell tumor of the thumb proximal phalanx: resection-iliac graft and double arthrodesis. Chir Main. 2008;27:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker W.T., Dohle J., Bernd L. Local recurrence of giant cell tumor of bone after intralesional treatment with and without adjuvant therapy. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2008;90:1060–1067. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trieb K., Bitzan P., Lang S., Dominkus M., Kotz R. Recurrence of curetted and bone-grafted giant-cell tumours with and without adjuvant phenol therapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:200–202. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Errani C., Ruggieri P., Asenzio M.A. Giant cell tumor of the extremity: a review of 349 cases from a single institution. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones K.B., DeYoung B.R., Morcuende J.A., Buckwalter J.A. Ethanol as a local adjuvant for giant cell tumor of bone. Iowa Orthop J. 2006;26:69–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcove R.C., Weis L.D., Vaghaiwalla M.R., Pearson R., Huvos A.G. Cryosurgery in the treatment of giant cell tumors of bone. A report of 52 consecutive cases. Cancer. 1978;41:957–969. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197803)41:3<957::aid-cncr2820410325>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malawer M.M., Bickels J., Meller I., Buch R.G., Henshaw R.M., Kollender Y. Cryosurgery in the treatment of giant cell tumor. A long-term follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;359:176–188. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199902000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Algawahmed H., Turcotte R., Farrokhyar F., Ghert M. High-speed burring with and without the use of surgical adjuvants in the intralesional management of giant cell tumor of bone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sarcoma. 2010:5. doi: 10.1155/2010/586090. Article ID 586090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas S., Henshaw R., Skubitz K. Denosumab in patients with giant cell tumour of bone:an open-label, phase 2 study. Oncol Lancet. 2010;11:275–280. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nouri H., Meherzi M.H., Ouertatani M. Use of calcitonin in giant cell tumors of bone. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balke M., Campanacci L., Gebert C. Bisphosphonate treatment of aggressive primary, recur-rent and metastatic giant cell tumour of bone. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:462–470. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouin F., Dumaine V., French Sarcoma and Bone Tumor Study Groups GSF-GETO Local recurrence after curettage treatment of giant cell tumors in peripheral bones: retrospective study by the GSF-GETO (French Sarcoma and Bone Tumor Study Groups) Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:S313–S318. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickson B.C., Li S.Q., Wunder J.S. Giant cell tumor of bone express p63. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:369–375. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams J., Hodari A., Janevski P., Siddiqui A. Recurrence of giant cell tumors in the hand: a prospective study. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scully S.P., Mott M.P., Temple H.T., O'Keefe R.J., O'Donnell R.J., Mankin H.J. Late recurrence of giant-cell tumor of bone: a report of four cases. J Bone Jt Surg. 1994;76A:1231–1233. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199408000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson K., Key C.H., Fontaine M., Pope R. Recurrence of a giant cell tumor of the hand after 42 Years: case report. J Hand Surg. 2012;37A:783–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]