Abstract

Introduction

Hearing impairment is highly prevalent and independently associated with cognitive decline. The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders study is a multicenter randomized controlled trial to determine efficacy of hearing treatment in reducing cognitive decline in older adults. Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT03243422.

Methods

Eight hundred fifty participants without dementia aged 70 to 84 years with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment recruited from four United States field sites and randomized 1:1 to a best-practices hearing intervention or health education control. Primary study outcome is 3-year change in global cognitive function. Secondary outcomes include domain-specific cognitive decline, incident dementia, brain structural changes on magnetic resonance imaging, health-related quality of life, physical and social function, and physical activity.

Results

Trial enrollment began January 4, 2018 and is ongoing.

Discussion

When completed in 2022, Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders study should provide definitive evidence of the effect of hearing treatment versus education control on cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment.

Keywords: Clinical trials, Cognition, Dementia, Epidemiology, Hearing, Longitudinal study, Memory, Presbycusis

1. Introduction

Peripheral hearing impairment, as measured with pure tone audiometry, has been shown in recent population-based observational studies to be strongly and consistently related to accelerated cognitive decline [1] and increased dementia risk in older adults [2]. Hypothesized pathways underlying this association include effects of distorted peripheral encoding of sound on cognitive load, changes in brain structure/function, and/or reduced social engagement [3]. Importantly, these pathways may be modifiable with comprehensive hearing treatment and rehabilitation. Two-thirds of adults older than 70 years have a clinically meaningful hearing impairment that may affect daily communication [4], [5]. Given this high prevalence and its strong association with incident dementia, if hearing loss is causally related to dementia, it is estimated that up to 9% of dementia cases in the world could potentially be prevented with hearing treatment and rehabilitation [2]. However, hearing aids remain grossly underutilized—less than 20% of adults with hearing impairment in the United States [6] use a hearing aid, with similar low utilization patterns in other comparable countries [7].

Most observational studies suggest a trend associating self-reported hearing aid use with better cognitive function [8], [9], [10]. However, data on key variables (e.g., years of hearing aid use, adequacy of hearing aid fitting, and rehabilitation) that would affect the success of hearing treatment—and therefore any observed association—have not been available in these studies [11]. In addition, results from observational studies should be interpreted with caution as individuals who choose to use a hearing aid likely differ significantly from individuals who do not in both measured and unmeasured factors that may impact cognition (e.g., socioeconomic status, health-seeking behaviors). Consequently, determining whether hearing rehabilitative strategies could delay cognitive decline will likely never be answered definitively from observational studies alone, and therefore will require a randomized trial.

Here we describe the study design of the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomized controlled trial, a large multicenter randomized trial designed to determine efficacy of hearing treatment in delaying cognitive decline in older adults. ACHIEVE is a study of 850 older adults without dementia aged 70 to 84 years with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment randomized 1:1 to a best-practices hearing intervention or successful aging health education control. The ACHIEVE trial is partially nested within the larger observational prospective Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study [12].

2. Study objectives

The primary objective of the ACHIEVE study is to determine efficacy of a best-practices hearing rehabilitative intervention versus a successful aging health education control on rates of 3-year decline in a global cognitive function in 70 to 84 year-old well-functioning older adults without dementia who have mild-to-moderate hearing impairment.

Secondary cognitive outcomes include domain-specific cognitive declines (memory, executive function, and language) and a composite outcome of adjudicated incident dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or a 3-point decline in the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [13]. Other secondary outcomes include brain structure on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), health-related quality of life, physical and social function, and physical activity.

3. Methods

3.1. ACHIEVE design, participants, and setting

ACHIEVE is a randomized, controlled multicenter superiority trial of 850 older adults with two parallel groups (best-practices hearing intervention vs. successful aging health education control) and a primary end point of 3-year change in global cognitive function. Stratified randomization is performed as permuted block randomization with a 1:1 allocation. Four ACHIEVE intervention visits occur within 8 to 10 weeks (one every 1–3 weeks) postrandomization with booster sessions every 6 months postrandomization up to 30 months. ACHIEVE clinic visits occur at 6 months (limited assessment battery and first intervention booster session) and annually for 3 years (Table 1). Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03243422.

Table 1.

Schedule of enrollment, interventions, and assessments: the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomized trial

| Timepoint | Study period |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment |

Allocation |

Postallocation |

Close-out |

|||||||||

| −30 to −1 d | Day 0 | 1–3 wk | 3–5 wk | 6–8 wk | 8–10 wk | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 24 mo | 30 mo | 36 mo | |

| Enrollment | ||||||||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | X | ||||||||||

| Informed consent | X | X | ||||||||||

| Demographics | X | |||||||||||

| Health history | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Vision screening | X | |||||||||||

| ADLs | X | |||||||||||

| Randomization | X | |||||||||||

| Interventions | ||||||||||||

| Hearing | X | X | X | X | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | |||

| Successful aging | X | X | X | X | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | X (booster) | |||

| Assessments | ||||||||||||

| Audiometric battery | ||||||||||||

| Air conduction audiometry | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Bone conduction audiometry | X | X∗ | X∗ | X∗ | ||||||||

| Tympanometry | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Word recognition in quiet | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Quick speech-in-noise (unaided) | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Cognition (primary outcome) | ||||||||||||

| Speech understanding | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| MMSE | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Delayed word recall | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Digit symbol substitution | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Incidental learning | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Trail making parts A and B | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Logical memory | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Digit span backward | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Boston Naming Test | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Word fluency | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Animal naming | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Secondary outcomes | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Clinical dementia rating | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Dementia/MCI evaluation | X∗ | X∗ | X∗ | X∗ | ||||||||

| Brain MRI† | X | X | ||||||||||

| Qualifying adverse events | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CES-D Scale | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Physical activity survey | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| HHIE-screening | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| RAND-36 health survey | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cohen Social Network Index | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| UCLA Loneliness Scale | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Accelerometry | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Falls and mobility | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Hospitalizations | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Grip strength | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| SPPB | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Hearing health and noise exposure | X | |||||||||||

| Anthropometry | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Seated blood pressure | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Blood draw for APOE‡ | ||||||||||||

| WRAT | X | |||||||||||

| Neurologic history | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; HHIE, hearing handicap for the elderly; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPPB, short physical performance battery; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; WRAT, Wide Range Achievement Test.

Procedures optional per protocol.

Brain MRI in a subset of participants. Baseline scan can occur up to 18 months before or up to 3 months postrandomization. Follow-up MRI will occur at least 3 years postrandomization.

Denotes procedures needed only for participants recruited de novo from the community.

Approximately half of ACHIEVE participants will be recruited from the ARIC cohort study, and half de novo from the surrounding communities. ARIC is a mostly biracial prospective study of 15,792 men and women aged 45 to 64 years in 1987 to 1989 from four US communities: Forsyth County, NC; Jackson, MS; selected suburbs of Minneapolis, MN; and Washington County, MD.

The ARIC Data Coordinating Center at the University of North Carolina also coordinates ACHIEVE data management. ACHIEVE and ARIC clinic visits are coordinated to maximize efficiency and minimize participant burden. Informed consent is obtained from all participants at the baseline visit, and study procedures are approved by the Institutional Review Board governing each field center.

3.2. Eligibility

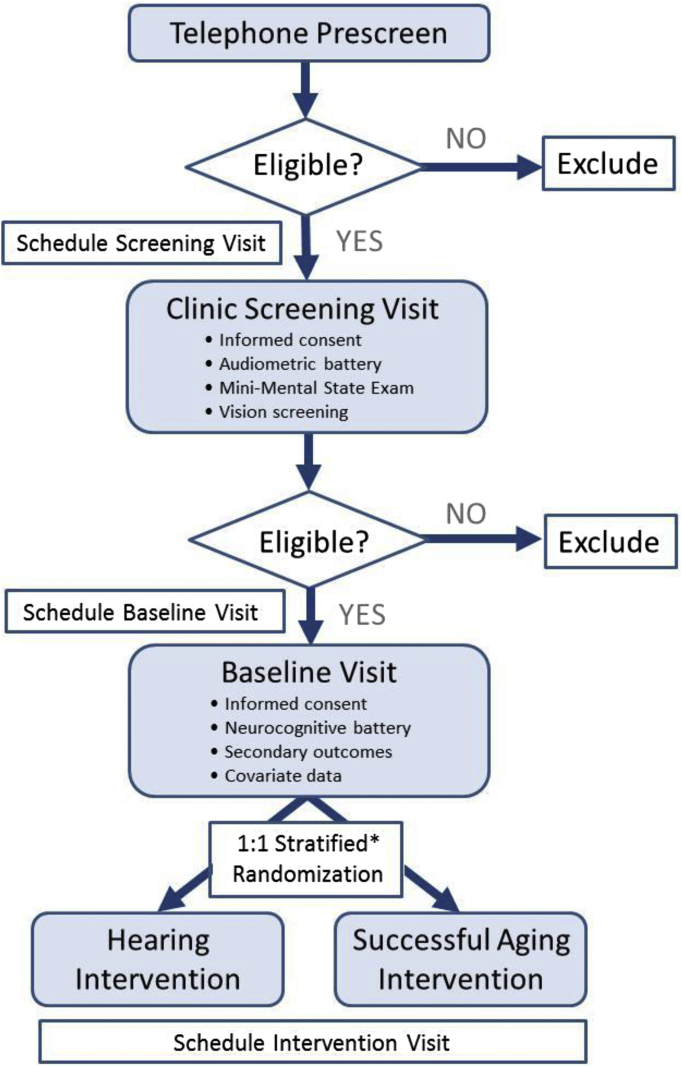

Eligibility criteria are designed to identify community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment who are at risk for cognitive decline and may possibly benefit from hearing treatment and rehabilitation. Participants are prescreened by telephone and complete a screening evaluation at a follow-up clinic visit (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant screening and randomization: the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomized trial. ∗Strata defined by severity of hearing impairment, participant status (ARIC participant or recruited de novo), and field site.

3.2.1. Inclusion criteria

ACHIEVE participants are adults aged 70 to 84 years with untreated adult-onset bilateral hearing impairment, defined as a better-hearing ear 4-frequency pure tone average (PTA, average of the threshold levels for the pure tone frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear) ≥30 and <70 dB hearing level who do not have dementia (MMSE ≥23 if high school degree or less and ≥25 if some college or more) [14]. Consistent with hearing impairment that is likely to benefit from amplification, participants have a Word Recognition in Quiet score ≥60% correct in the better-hearing ear. Participants are community-dwelling with plans to remain in the area during the study period and are fluent English speakers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) randomized trial

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Inclusion |

|

| Exclusion |

|

Abbreviations: HL, hearing level; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

3.2.2. Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria include prior dementia diagnosis, self-reported difficulty in ≥2 activities of daily living [15], vision impairment that may interfere with cognitive testing (worse than 20/60 with correction on Minnesota Near Vision Card), medical contraindication to hearing treatment (e.g., draining ear), untreatable conductive hearing impairment (difference in air audiometry and bone audiometry, or “air-bone gap,” >15 dB in two or more contiguous frequencies in both ears that cannot be medically resolved), or unwillingness to regularly wear hearing aids (Table 2).

3.3. Recruitment

ACHIEVE recruitment began January 4, 2018 with completion anticipated May 2019. Field sites employ site-specific strategies that have demonstrated prior success with recruitment of older adults, including use of established research registries, targeted advertisements in aging-related publications and other media, established field site relationships with local churches/retirement centers, mass mailings, and so forth.

3.4. Randomization

The ACHIEVE Data Coordinating Center oversees the randomization process and generated the allocation schedule. After final determination of eligibility and confirmation of informed consent, participants are randomized 1:1 to the hearing intervention or to the successful aging education control. To ensure balance between the treatment groups, participants are randomized in permuted order blocks of varying sizes within strata defined by severity of hearing impairment—mild (PTA ≥30 and <40 dB) or moderate to moderate (PTA ≥40 and <70 dB), participant status (ARIC participant or recruited de novo), and by field site. Field center staff are masked to block size.

3.5. Masking

Neither study participants nor study technicians collecting outcome data can feasibly be masked (blinded) to randomization status. Precautions to minimize potential bias resulting from the lack of masking include use of an established attention control intervention (i.e., to optimize participant retention across both study arms) [16]; masking of participants to the study hypothesis; use of standardized protocols for training of data collectors and assessment of study outcomes; lack of access to cognitive testing results from prior study visits for data collectors and study coordinators to avoid unintentional and possibly unconscious bias by study staff during data collection; and masking of accumulating trial data from ACHIEVE principal investigators, coinvestigators, and key project staff.

3.6. Study interventions

Participants are randomized 1:1 to a best-practices hearing intervention or to a successful aging health education control. Both interventions were successfully piloted for feasibility in a 6-month 40-person ACHIEVE-Pilot study conducted at the ARIC Washington County site with no treatment-related adverse events [17].

3.6.1. Ethics of the use of a health education control

Use of a health education control is deemed ethical, as currently there is no established usual or standard-of-care for reducing cognitive decline in older adults without dementia [18]. There is also no established usual care for the management of hearing loss in older adults; a recent report from the United States Preventative Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to recommend hearing loss screening or treatment for adults 50 years or older [19]. Participants in each treatment arm will be offered and provided the other study intervention at the conclusion of the trial.

3.6.2. Best-practices hearing intervention

Developed at the University of South Florida, the main objective of the hearing intervention is to minimize activity limitations and participation restrictions due to hearing impairment. Using evidence-based best practices [20], the intervention includes individual needs assessment, goal-setting [21], engagement in shared-informed decision-making, and the development of self-management abilities for hearing loss and communication in real-world settings (e.g., understanding hearing loss, realistic expectations, communicating in background noise, using communication strategies and tactics, and resources for adults with hearing loss and their communication partners).

The hearing intervention consists of four 1-hour sessions with a research audiologist held every 1 to 3 weeks postrandomization. Participants receive bilateral receiver-in-the-canal hearing aids fit to prescriptive targets using real-ear measures and other hearing assistive technologies to pair with the hearing aids (e.g., devices to stream cell phones and television, remote microphones to directly access other speakers in difficult listening environments). The intervention includes systematic orientation and instruction in device use and hearing “toolkit” materials for self-management and communication strategies.

Reinstruction in use of devices and hearing rehabilitative strategies is provided during booster visits held every 6 months postrandomization. Unscheduled interim visits may also be sporadically required (e.g., hearing aid malfunction), and these visits to troubleshoot hearing aids are scheduled as needed if the issue cannot be resolved with a telephone conversation.

3.6.3. Communication partners for participants randomized to the hearing intervention

Communication partners or adults who communicate with ACHIEVE participants on a daily or near-daily basis (e.g., spouse) are often a key to successful intervention for older adults with hearing impairment. Communication partners for participants randomized to the hearing intervention are invited to join the study and to contribute data related to their own quality of life and their observations of the effects of the hearing intervention on the participant. Communication partners are encouraged to attend hearing intervention sessions as part of the intervention.

3.6.4. Successful aging health education control intervention

The successful aging control follows the protocol and materials developed for the 10 Keys to Healthy Aging [22], an evidence-based interactive health education program for older adults on topics relevant to chronic disease and disability prevention, which has been previously implemented in other trials [23], [24]. It contains the most up-to-date prevention guidelines available based on the current recommendations from leading groups such as the United States Preventive Services Task Force, Centers for Disease Control, and National Academy of Sciences.

To control for general levels of staff and participant time and attention, participants randomized to this group meet individually with a certified health educator who administers the program every 1 to 3 weeks for a total of four visits over ∼2 to 3 months. Session content is tailored to each participant and includes a standardized didactic education component as well as activities, goal-setting, and optional extracurricular enrichment activities. To further enhance retention and perceived benefit, each session also includes a 5- to 10-minute upper body extremity stretching program [25]. To match the contact schedule with the hearing intervention and promote retention, participants return for booster sessions semiannually.

3.7. Study measures

Table 1 summarizes ACHIEVE assessments. Although study personnel collecting cognitive data cannot feasibly be masked to participant intervention assignment, they are masked to outcome data assessed at previous visits.

3.7.1. Primary outcome

The primary study outcome is the change from baseline to year 3 in a global cognitive function factor score derived from a full neuropsychological battery with tests representing multiple cognitive domains, including memory, language, and executive function/attention (Table 1). Factor scores are developed using a latent variable modeling approach and have been previously used and validated in the observational ARIC cohort [26]. Compared with other summary measures, such as weighted averages (e.g., z-scores), the factor scores better account for measurement error of individual tests and their relative difficulty [26] and improve precision [27]. The neurocognitive battery is collected at the baseline visit and annually thereafter for 3 years (Table 1).

Because ACHIEVE participants have mild-to-moderate hearing impairment, a brief test is conducted before the neurocognitive assessment to determine whether the participant can adequately hear the examiner. Developed by coinvestigators with neuropsychological expertise, this brief test, in conjunction with a standardized protocol that includes face-to-face communication in a quiet room and presentation of both written and verbal testing instructions, ensures sufficient access to the verbal test instructions and reduces hearing impairment as a direct confound in the neurocognitive testing and any measured efficacy signal for the hearing (vs. successful aging) intervention.

3.7.2. Secondary outcomes

Key secondary outcomes include 3-year change in cognitive domain-specific latent factor scores (memory, executive function, and language) and time until meeting a composite outcome consisting of adjudicated incident dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or a 3-point MMSE decline. Syndromic diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia is obtained by standardized algorithms incorporating cognitive test scores, cognitive decline across prior study visits, and subject and informant interviews, followed by expert-adjudicated review [28].

Other secondary outcomes include brain structural characteristics from MRI (from a subsample) and functional outcomes independently associated with hearing impairment, including health-related quality of life, social factors (loneliness and social network), hospitalizations, falls, physical function, and physical activity (Table 2).

3.7.3. Audiometric measures

All participants receive a full audiometric battery at screening and at annual follow-up visits (Table 1). In participants randomized to the hearing intervention, audiologic outcomes to verify the intervention (e.g., hearing aid data logging, real-ear measures, aided speech-in-noise) are gathered semiannually beginning 6 months postrandomization.

3.7.4. Covariates

Demographic factors, medical history, and other clinical factors are collected at baseline and annually. Within 6 months of baseline, blood will be drawn for apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping from non-ARIC participants; APOE ε4 status of ARIC participants has already been established (Table 1).

3.8. Statistical Considerations

3.8.1. Sample size

We estimate a sample size of N = 850 provides 90% power to detect a standardized effect size of 0.26 (80% power for a standardized effect size of 0.23) for the difference between intervention groups in the mean change from baseline in global cognition factor score at 3 years, based on a two-sided t test and 5% type I error rate. These estimates account for a conservative net total of 15% drop-in (uptake of hearing aids in the control group) and dropout (discontinuation of hearing aid use in the hearing intervention group).

3.8.2. Statistical methods

The primary analysis will compare change in the global cognitive function factor score from baseline to year 3 in the hearing intervention group versus the successful aging health education control for the intent-to-treat population, which includes all randomized subjects using a multiple imputation analysis of covariance model with adjustment for age, education (≤high school vs. >high school), an interaction term between race and study site, baseline global cognition factor score, baseline hearing loss, and participant recruitment status (from ARIC or de novo from the community).

Because dropout due to dementia may bias (underestimate) the relationship between intervention assignment and cognitive change, for ACHIEVE participants who are diagnosed with dementia during follow-up but do not attend the year 3 clinic visit (and so are missing the year 3 cognitive score), the missing year 3 cognitive score will be imputed using cognitive and other data from other ACHIEVE dementia cases, as well as from non-ACHIEVE ARIC participants who are diagnosed with dementia during a prespecified calendar period aligning with the ACHIEVE follow-up time. Other missing cognitive scores (e.g., missing for reasons other than dementia diagnosis) will be imputed using ACHIEVE data under the missing at random assumption.

For analysis of the key secondary outcomes, treatment group comparisons will be adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Hochberg modification to the Bonferroni method, so as to minimize the probability of a significant association due to chance [29].

A secondary analysis of the primary outcome will be completed for the per-protocol population, defined as a subset of the intention-to-treat population who completed the 8- to 10-week intervention period, had no hearing aid intervention drop-in for the control group, and had no major protocol deviations. Major protocol deviations include violations in inclusion and exclusion criteria at enrollment and poor compliance with hearing aids for the hearing aid intervention group, defined as subjects who discontinue hearing aid use at any time during the study period.

An interim analysis to evaluate for sample-size re-estimation based on conditional power will be performed after 66% of subjects have completed the study. If the conditional power is in the promising zone [30], the sample size may be increased up to 100% (850 additional participants) to increase conditional power up to 80%. In the unexpected event of low study enrollment, an assessment for futility may also be performed at this interim.

3.9. Safety monitoring

Study participation and exposure to the hearing aid intervention is expected to have a low risk of participant adverse events. To efficiently collect safety information relevant to study participation, interventions, and procedures, detailed information concerning a prespecified set of adverse events and serious adverse events is collected and evaluated throughout the trial, and is monitored by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

4. Discussion

Dementia is a global public health priority [31] and arguably the greatest current challenge to health and social care systems [2]. Novel approaches are urgently needed to reduce risk of age-related cognitive decline in older adults [18]. The ACHIEVE study is the first large multicenter randomized controlled study to determine the efficacy of a best-practices hearing intervention (vs. successful aging health education control) for the delay of 3-year cognitive decline in older adults aged 70 to 84 years with untreated mild-to-moderate hearing impairment. Trial enrollment started on January 4, 2018 and recruitment is ongoing.

Nesting of ACHIEVE within a large, well-characterized multicenter observational study with over 30 years of follow-up maximizes both operational (dedicated study staff, well-established protocols, and study staff-participant relationships) and scientific efficiency. Thirty years of prior longitudinal cognitive data are available for participants recruited from ARIC, allowing for a secondary investigation of whether the hearing rehabilitation intervention alters a participant's established prior trajectory of cognitive decline. Brain MRI and amyloid measured by positron emission tomography are also available for a subset of these participants.

Whether hearing treatment and rehabilitation can delay cognitive decline in at-risk older adults is unknown, but could have substantial clinical, social, and public health impact as evidenced by recent national initiatives focused on hearing loss [7], [32]. When completed in 2022, ACHIEVE should provide definitive evidence of the effect of hearing treatment on cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Literature review included traditional sources. Hearing impairment is highly prevalent and independently associated with cognitive decline in observational studies. However, determining whether hearing rehabilitation delays cognitive decline will likely never be answered definitively from observational studies alone, therefore requiring a randomized trial.

-

2.

Interpretation: The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) study is the first large, multicenter randomized controlled study to determine efficacy of a best-practices hearing intervention (vs. successful aging health education control) for the delay of 3-year cognitive decline in adults aged 70 to 84 years with untreated hearing impairment. Enrollment began January 2018 and is ongoing.

-

3.

Future directions: Whether hearing treatment delays cognitive decline in at-risk older adults is unknown, but could have substantial clinical, social, and public health impact. When completed in 2022, ACHIEVE should provide definitive evidence of the effect of hearing treatment on cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate hearing impairment.

Acknowledgments

The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) R01AG055426, with previous pilot study support from the NIA 1R34AG046548-01A1 and the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation, in collaboration with the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Neurocognitive data in ARIC is collected by U01 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, and 2U01HL096917 from the National Institute of Health (NHLBI, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIA, and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders), and with previous brain magnetic resonance examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ACHIEVE and ARIC studies for their important contributions. J.A.D. is supported by NIA K01AG23291.

F.R.L. is a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cochlear Ltd, and Amplifon. V.A.S is a consultant to Autifony Therapeutics Ltd, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Otonomy Inc.

References

- 1.Loughrey D.G., Kelly M.E., Kelley G.A., Brennan S., Lawlor B.A. Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;144:115–126. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston G., Sommerlad A., Orgeta V., Costafreda S.G., Huntley J., Ames D. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin F.R., Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia—who is listening? Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:671–673. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin F.R., Niparko J.K., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1851–1852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goman A.M., Lin F.R. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1820–1822. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chien W., Lin F.R. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:292–293. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2016. Hearing health care for adults: priorities for improving access and affordability. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amieva H., Ouvrard C., Giulioli C., Meillon C., Rullier L., Dartigues J.F. Self-reported hearing loss, hearing aids, and cognitive decline in elderly adults: a 25-year study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2099–2104. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deal J.A., Sharrett A.R., Albert M.S., Coresh J., Mosley T.H., Knopman D. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline: a pilot study conducted within the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:680–690. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin F.R., Metter E.J., O'Brien R.J., Resnick S.M., Zonderman A.B., Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:214–220. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez E., Edmonds B.A. A systematic review of studies measuring and reporting hearing aid usage in older adults since 1999: a descriptive summary of measurement tools. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Prevention of blindness and deafness grades of hearing impairment. http://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/hearing_impairment_grades/en/ Available at:

- 15.Katz S., Ford A.B., Moskowitz R.W., Jackson B.A., Jaffe M.W. Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutron I., Guittet L., Estellat C., Moher D., Hrobjartsson A., Ravaud P. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deal J.A., Albert M.S., Arnold M., Bangdiwala S.I., Chisolm T., Davis S. A randomized feasibility pilot trial of hearing treatment for reducing cognitive decline: results from the Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders Pilot Study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plassman B.L., Williams J.W., Jr., Burke J.R., Holsinger T., Benjamin S. Systematic review: factors associated with risk for and possible prevention of cognitive decline in later life. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:182–193. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyer V.A., U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for hearing loss in older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:655–661. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valente M., Abrams H., Benson D., Chisolm T., Citron D., Hampton D. Guidelines for the audiologic management of adult hearing impairment. Audiology Today. 2006;18:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon H., James A., Ginis J. Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman A.B., Bayles C.M., Milas C.N., McTigue K., Williams K., Robare J.F. The 10 Keys to healthy aging: findings from an innovative prevention program in the community. J Aging Health. 2010;22:547–566. doi: 10.1177/0898264310363772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morone N.E., Greco C.M., Rollman B.L., Moore C.G., Lane B., Morrow L. The design and methods of the Aging Successfully with Pain Study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venditti E.M., Zgibor J.C., VanderBilt J., Kieffer L.A., Boudreau, Burke L.E. Mobility and Vitality Lifestyle Program (MOVE UP): a community health worker intervention for older adults with obesity to improve weight, health, and physical function. Innov Aging. 2018;2 doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fielding R.A., Rejeski W.J., Blair S., Church T., Espeland M.A., Gill T.M. The Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders Study: design and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1226–1237. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross A.L., Power M.C., Albert M.S., Deal J.A., Gottesman R.F., Griswold M. Application of latent variable methods to the study of cognitive decline when tests change over time. Epidemiology. 2015;26:878–887. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross A.L., Sherva R., Mukherjee S., Newhouse S., Kauwe J.S., Munsie L.M. Calibrating longitudinal cognition in Alzheimer's disease across diverse test batteries and datasets. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43:194–205. doi: 10.1159/000367970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knopman D.S., Gottesman R.F., Sharrett A.R., Wruck L.M., Windham B.G., Coker L. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS) Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;2:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta C.R., Pocock S.J. Adaptive increase in sample size when interim results are promising: a practical guide with examples. Stat Med. 2011;30:3267–3284. doi: 10.1002/sim.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/. Accessed April, 2018.

- 32.President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, ed. Aging America and hearing loss: imperative of improved hearing technologies; 2015.