Abstract

Magical ideation refers to beliefs about causality that lack empirical bases. Few studies have investigated the neural correlates of magical thinking and religious beliefs. Here, we investigate the association between magical ideation and religious experience in a sample of Vietnam veterans who sustained penetrating traumatic brain injury (pTBI) and matched healthy controls (HCs). Scores on the Magical Ideation Scale were positively correlated with scores on the Religious Experience Scale, but only in pTBI patients. Lesion mapping analyses in subgroups of pTBI patients indicated that prefrontal cortex (PFC) lesions were associated with increased magical ideation scores and this relationship was mediated by religious experience. Our findings clarify the mechanism by which the frontal lobe processes modulate magical beliefs. Suppression of the PFC opens people to religious experiences, which in turn increases magical ideation.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, prefrontal cortex, religious beliefs, magical ideation

Introduction

Magical ideation refers to uncanny beliefs about causality that lack an empirical basis. (Eckblad & Chapman, 1983). Religious beliefs are often included in magical thinking (e.g., belief in the existence of a tangible God), yet they differ in several ways. Those who hold religious beliefs are in many respects similar to skeptics insofar as strong religious commitments typically exclude non-traditional paranormal beliefs, whereas magical thinking accepts a broader bandwidth of supernatural causation (Wilson, Bulbulia, & Sibley, 2014).

The burgeoning neuroscience of belief (Kapogiannis et al., 2009; McNamara, 2006) has yet to investigate the neural mechanisms that support magical ideation, in patients with brain lesions. It has long been speculated that magical thinking gave rise to religious beliefs in human history (Malinowski, 1948). However the proximate underpinnings of magical and religious beliefs are unclear. Here, combining lesion mapping, neuropsychological methods and mediation analyses, we tested the relationship between magical ideation and religious experience in a sample of Vietnam veterans with penetrating traumatic brain injury (pTBI) and matched healthy controls (HCs). A better understanding of religious beliefs has wide implications for peace and conflict, since religion is an important tool for organizing societies and mobilizing collective action, including cooperation and aggression (Atran & Ginges, 2012).

Methods

Participants

Our sample included 117 veterans with pTBI and 32 HCs (who also served in combat during the Vietnam War but did not sustain any brain-injury) participating in the Vietnam Head Injury Study (VHIS), a longitudinal study of Vietnam War veterans who sustained focal pTBI (Raymont, Salazar, Krueger, & Grafman, 2011). Table 1 reports demographic information of the sample. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Written consent was provided by all participants.

Table 1.

Demographic and neuropsychological measures for TBI patients (n = 117) and HC (n = 32).

| TBI (n = 117) | HC (n = 32) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.38 ± 2.96 | 62.97 ± 3.45 | U = 2090, Z = −1.02, p = 0.31 |

| Education | 14.64 ± 2.25 | 15.09 ± 2.15 | U = 1677, Z = −0.92, p =0.36 |

| Handedness (R:L:A) | 94:21:2 | 26:4:2 | χ2 = 2.38, df = 2, p = 0.30 |

| Pre-injury AFQT | 66.10 ± 22.98 | 71.59 ± 17.65 | U = 1010, Z = −0.92, p = 0.36 |

| Post-injury AFQT | 57.29 ± 25.31 | 73.19 ± 19.49 | U = 1098, Z = −3.23, p = 0.001 |

| Naming | 54.05 ± 5.91 | 55.65 ± 3.93 | U = 1493, Z = −1.33, p = 0.18 |

| Token Test | 98.16 ± 2.47 | 98.47 ± 1.87 | U = 1775, Z = −0.24, p = 0.81 |

| Trait Anxiety | 47.96 ± 10.68 | 53.32 ± 13.60 | U = 1397, Z = −1.96, p = 0.05 |

| Sorting | 10.65 ± 3.14 | 12.70 ± 2.97 | U = 1043, Z = −3.20, p = 0.001 |

| Trail Making | 9.42 ± 3.81 | 11.00 ± 2.60 | U = 1299, Z = −2.04, p = 0.04 |

| Fluency | 8.84 ± 3.45 | 10.53 ± 3.83 | U = 1294, Z = −2.22, p = 0.03 |

| Magical Ideation | 1.41 ± 0.17 | 1.37 ± 0.15 | U = 2070, Z = −0.92, p = 0.36 |

| Religious Experience | 4.51 ± 1.39 | 3.91 ± 1.55 | U = 2270, Z = −1.84, p = 0.07 |

Neuropsychological measures

Participant underwent extensive neuropsychological testing during their 5-day evaluation at the NINDS (see Supplementary Methods).

Magical ideation was assessed using 17 items from the Magical Ideation Scale (Eckblad & Chapman, 1983), which consists of true (scored 2) or false (scored 1) questions about beliefs in magical influences (glb coefficient = 0.79). The scale was originally developed to detect schizotypical behavior in the hopes of devising a scale to predict the later development of schizophrenia in college age students. Most questions ask about a subject’s interpretation of personal experiences, such as thought transmission, psychokinetic effects, precognition, spirit influences and good luck charms (e.g. “I have had the momentary feeling that someone’s place has been taken by a look-alike”).

Religious experience was assessed using the revised version of the Religious Experience Questionnaire (REQ;Edwards, 1976), which consists of 12 items that reflect a personal affective relationship with God and the perceived influence of God in one’s life (glb coefficient = 0.97), including feelings of being forgiven for sins and referring to God when making decisions (e.g. “I experience an awareness of God’s love”). The items were rated on a 7-point Likert-scale (1=never, 7=always).

Magical ideation and religious experience scores were computed for each participant by averaging responses to all scale items.

Executive function was assessed using three D-KEFS tests: Sorting, Trail Making and Verbal Fluency (see Supplementary Methods). Higher scores indicate better performance in the executive function tests. Additional measures (e.g., trait anxiety, intelligence) were also administered and are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Computed Tomography acquisition and Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping

Computed Tomography (CT) scans were obtained and lesion volume and location were determined as described in the Supplementary Methods.

Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping (VLSM) analysis was conducted to analyze the relationship between lesion and behavior on a voxel-by-voxel basis. Four TBI subgroups were selected based on median split analyses on magical ideation scores and religious experience scores: (1) both high magical ideation scores and high religious experience scores (MHRH, N=33); (2) high magical ideation scores but low religious experience scores (MHRL, N=23); (3) low magical ideation scores but high religious experience scores (MLRH , N=24); and (4) both low magical ideation scores and low religious experience scores (MLRL, N=37). For each subgroup of pTBI patients, magical ideation scores were compared between pTBI and HCs at each voxel using the Mann-Whitney U test, corrected at a false discovery rate of 0.05 (1-tailed), with a minimum cluster size of 10 voxels, and a minimum number of four participants with overlapping lesions at any voxel.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R 3.4.1. Statistical significance level was assessed at the traditional p< 0.05 level (two-tailed) for all analyses. Correlations were computed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Mediation analysis was performed by entering PFC lesion size as the independent variable, religious experience score as the mediator and magical ideation score as the dependent variable (see Supplementary methods). The bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were computed from 5000 bootstrap samples to evaluate the size of the indirect effect.

Results

Behavioral results

Neuropsychological measures for the pTBI and HC groups are reported in Table 1. The pTBI group and HC group were matched on most neuropsychological measures. The pTBI group showed lower post-injury intelligence than HCs (Z=−3.23, p=0.001), but their scores were within normal range. Although prior research suggested that religiosity shows overall negative correlations with intelligence, there was no significant correlation between intelligence and religious experience in either group (all p’s>0.1). Patients with pTBI reported lower trait anxiety than HCs (Z=−1.96, p=0.05) and performed worse than HCs on executive function tests (p<0.05 for all three tests).

The pTBI and HC groups did not reliably differ in magical ideation (Z=−0.92, p=0.36), but the pTBI group reported marginally higher religious experience scores than the HC group (Z=−1.84, p=0.07). Magical ideation was associated positively with religious experience in pTBI patients (rho=0.29, p=0.001) but not in HCs (rho=0.18, p=0.33). Trait anxiety was positively associated with magical ideation in pTBI patients (rho=0.28, p=0.002) but not in HCs (rho=0.08, p=0.68). Furthermore, magical ideation scores were negatively associated with trail making performance in pTBI patients (rho=−0.21, p=0.025), but there was no statistically significant association observed with executive function measures and magical ideation scores in HCs (all p’s>0.1). Magical ideation scores were not significantly associated with pre- or post-injury intelligence scores in either group (all p’s>0.05).

VLSM analysis

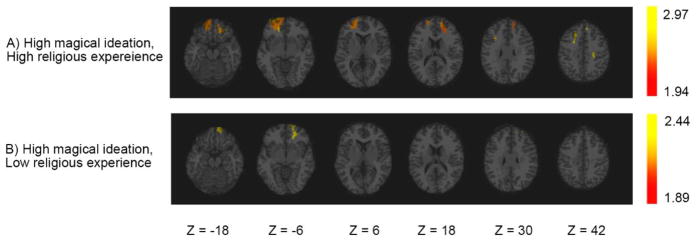

VLSM analyses were performed in each of four subgroups of pTBI patients with different combinations of levels of magical ideation and religious experience. Neuropsychological and demographic measures were matched across these subgroups (Table 2). Statistically significant clusters associated with increased magical ideation were found in the MHRH and MHRL groups (Figure 1). In the MHRH group, lesions associated with higher magical ideation were identified in the bilateral PFC, including the bilateral superior frontal gyrus (SFG), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC), gyrus rectus, anterior cingulate (ACC) and the right supplemental motor area (SMA). In the MHRL group, lesions to the left ventromedial PFC, including the left SFG, MFG, mOFC and gyrus rectus, were associated with higher magical ideation. See Table S1 for a list of clusters.

Table 2.

Demographic and neuropsychological measures for pTBI subgroups divided according to both magical ideation and religious experience scores.

| MHRH (n = 33) | MHRL (n = 23) | MLRH (n = 24) | MLRL (n = 37) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.64 ±2.42 | 62.74 ± 1.89 | 64.38 ± 4.50 | 62.92 ± 2.59 | χ2 = 4.29, p = 0.23 |

| Education | 15.00±2.68 | 14.74 ± 1.94 | 14.38 ± 2.30 | 14.43 ± 2.02 | χ2 = 1.45, p = 0.69 |

| Handedness(R :L:A) | 27:4:2 | 19:4:0 | 20:4:0 | 28:9:0 | χ2 = 6.73, p = 0.35 |

| Pre-injury AFQT | 65.17 ± 25.89 | 68.77 ± 20.83 | 66.59 ± 24.19 | 64.75 ± 21.62 | χ2 = 0.42, p = 0.94 |

| Post-injury AFQT | 55.84 ± 26.65 | 56.74 ± 30.40 | 56.79 ± 24.82 | 59.22 ± 21.62 | χ2 = 0.21, p = 0.98 |

| Naming | 54.81 ± 4.88 | 53.22 ± 5.75 | 53.70 ± 5.55 | 54.14 ± 7.09 | χ2 = 1.90, p = 0.59 |

| Token Test | 98.13 ± 2.08 | 98.17 ± 2.42 | 98.26 ± 2.68 | 98.11 ± 2.76 | χ2 = 0.60, p = 0.90 |

| Trait Anxiety | 51.33 ± 13.27 | 48.35 ± 8.95 | 44.92 ± 9.21 | 46.68 ± 9.48 | χ2 = 4.10, p = 0.25 |

| Sorting | 9.90 ± 3.26 | 10.48 ± 4.24 | 11.05 ± 2.30 | 11.17 ± 2.62 | χ2 = 3.17, p = 0.37 |

| Trail Making | 9.03 ± 3.89 | 8.22 ± 4.55 | 9.04 ± 4.15 | 10.78 ± 2.58 | χ2 = 5.14, p = 0.16 |

| Fluency | 9.24 ± 3.63 | 8.87 ± 4.50 | 8.33 ± 2.51 | 8.78 ± 3.16 | χ2 = 0.61, p = 0.89 |

| Magical Ideation | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 1.53 ± 0.09 | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 1.25 ± 0.08 | χ2 = 89.97, p < 0.001 |

| Religious Experience | 5.77 ± 0.51 | 3.41 ± 0.92 | 5.64 ± 0.56 | 3.35 ± 0.90 | χ2 = 87.19, p < 0.001 |

Figure 1.

VLSM analyses results for the (A) High magical ideation, high religious experience group, and (B) High magical ideation, low religious experience group. Color indicates the U-values: yellow represents higher U-values and orange indicates lower U-values. Images are in radiological convention: right hemisphere is on the reader’s left.

Mediation analysis

Results indicate that the effect of a PFC lesion on magical ideation is mediated through religious experience (indirect effect=0.0019, SE=0.0008, 95% CI=[0.0007, 0.0040]). However, we found no statistically significant mediation effect when the mediator and outcome variables were reversed (indirect effect=−0.0005, SE=0.0058, 95% CI=[−0.013,0.011]). Additionally, the mediation effect remained statistically significant (indirect effect=0.0016, SE=0.0008, 95% CI=[0.0005,0.0037]) when trait anxiety and trail making performance were included (both correlated with magical ideation in pTBI patients) as covariates.

Discussion

Previous research has found that the suppression of functionality in PFC is linked to both supernatural beliefs (Wain & Spinella, 2007) and supernatural experiences (Cristofori et al., 2016). Our findings are in accord with these frontal regulatory hypotheses. Exploratory lesion analyses in pTBI subgroups indicate that bilateral PFC lesions are associated with increased magical ideation. We contribute further precision to these hypotheses by revealing a mechanism through which magical beliefs and religious experiences are linked: (1) PFC damage is associated with greater religious experience, which in turn increases magical ideation; (2) the reverse pathway is not supported; we do not find evidence that having greater magical ideation increases religious experience. Thus, while magical and religious ideation are conceptually similar, these domains are differently modulated by frontal lobes.

Of course, it would be too simplistic to infer that such a mechanism explains religious and magical ideation. Other factors, such as intuitive cognitive style (Pennycook, Cheyne, Seli, Koehler, & Fugelsang, 2012), and dualism and teleology (Willard & Norenzayan, 2013), have been found to underpin both religious and supernatural beliefs. Cultural and social influence can play an additional role, and these factors should be considered in future studies of magical ideation and religious experience in patients with brain injuries.

Whether magical and religious experiences can be disentangled, and if so, how they are linked, remain topics of longstanding speculation (Malinowski, 1948). If the evolutionary problem is to express socially acceptable forms of supernatural ideation, then it is expected that socially marginal forms of supernatural ideation such as magic would conform to socially popular forms (aka religion), which help groups act in cohesive and coordinated ways, promoting both in-group solidarity and out-group biases. Despite theories that magical thinking renders religion plausible (Malinowski, 1948), our observation for a causal path from religion to magic is more consistent with the constraints imposed on beliefs dependent upon a social coordination system. The results also merge nicely with previous research on various aspects of human beliefs and bolster the important role that the human frontal lobes play in storing and modulating religious beliefs and related social and cognitive processes (Cristofori et al., 2016; Zhong, Cristofori, Bulbulia, Krueger, & Grafman, 2017).

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement.

The present study investigates the neural bases of magical ideation in patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury. The findings clarify the mechanisms by which the frontal lobes affect magical ideation: the suppression of the PFC opens people to religious experiences, which in turn support magical beliefs. In contrast, magical beliefs do not make people more prone to religious experiences.

Acknowledgments

We thank our Vietnam veterans for their dedicated participation in the study; J. Solomon for his assistance with ABLe; V. Raymont, S. Bonifant, B. Cheon, C. Ngo, A. Greathouse, K. Reding, and G. Tasick for testing and evaluating participants; and the National Naval Medical Center and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke for providing support and facilities. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

This study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Intramural Research Program, the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (WZ) and the Therapeutic Cognitive Neuroscience Fund (JG).

References

- AFQT-7A. Department of Defense Form 1293. 1960. Mar 1, [Google Scholar]

- Atran S, Ginges J. Religious and sacred imperatives in human conflict. Science. 2012;336(6083):855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.1216902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofori I, Bulbulia J, Shaver JH, Wilson M, Krueger F, Grafman J. Neural correlates of mystical experience. Neuropsychologia. 2016;80:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. The Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System: examiner’s manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Magical Ideation as an Indicator of Schizotypy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(2):215–225. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KJ. Sex-role behavior and religious experience. In: Donaldson WJ Jr, editor. Research in mental health and religious behavior: An introduction to research in the integration of Christianity and the behavioral sciences. Atlanta, GA: Psychological Studies Institute; 1976. pp. 224–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kapogiannis D, Barbey AK, Su M, Zamboni G, Krueger F, Grafman J. Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(12):4876–4881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makale M, Solomon J, Patronas NJ, Danek A, Butman JA, Grafman J. Quantification of brain lesions using interactive automated software. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2002;34(1):6–18. doi: 10.3758/bf03195419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski B. Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P. Where God and Science Meet: How Brain and Evolutionary Studies Alter Our Understanding of Religion. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil MM, Prescott TE. Revised Token Test. Los Angeles, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook G, Cheyne JA, Seli P, Koehler DJ, Fugelsang JA. Analytic cognitive style predicts religious and paranormal belief. Cognition. 2012;123(3):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Raymont V, Salazar AM, Krueger F, Grafman J. “Studying injured minds” - the Vietnam head injury study and 40 years of brain injury research. Front Neurol. 2011;2:15. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2011.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48(2):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J, Raymont V, Braun A, Butman JA, Grafman J. User-friendly software for the analysis of brain lesions (ABLe) Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2007;86(3):245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RVPR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15(1):273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain O, Spinella M. Executive functions in morality, religion, and paranormal beliefs. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117(1):135–146. doi: 10.1080/00207450500534068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard AK, Norenzayan A. Cognitive biases explain religious belief, paranormal belief, and belief in life’s purpose. Cognition. 2013;129(2):379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MS, Bulbulia J, Sibley CG. Differences and similarities in religious and paranormal beliefs: a typology of distinct faith signatures. Religion, Brain & Behavior. 2014;4(2):104–126. [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Grafton ST, Holmes CJ, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: I. General methods and intrasubject, intramodality validation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22(1):139–152. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Cristofori I, Bulbulia J, Krueger F, Grafman J. Biological and cognitive underpinnings of religious fundamentalism. Neuropsychologia. 2017;100:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.