Abstract

Chest pain is a common symptom culminating in hospital admissions and specialist referrals. Although cardiac work up is pursued in most of the cases, cardiac etiology is found to be the culprit in minority of the cases. Acute chest pain is a clinical syndrome that may be caused by almost any condition affecting the thorax, abdomen, or internal organs. On occasions this extensive and expensive diagnostic work up can be avoided with awareness of commoner and non-lethal reasons. We report a case of a woman with Bornholm disease secondary to Coxsackievirus B5 (CB5) infection and supplementary review of literature till date.

Keywords: Coxsackievirus, Chest pain, Chest X ray, Pleurodynia

1. Introduction

Chest pain is a common symptom culminating in hospital admissions and specialist referrals. Although cardiac work up is pursued in most of the cases, cardiac etiology is found to be the culprit in minority of the cases [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. Data from epidemiologic studies have indicated that the overall proportion of non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP) among patients with chest pain is reported between 20 and 40%.This fraction is robust and internationally similar in different countries, such as Germany Europe, USA, China, or Australia [6]. Acute chest pain is a clinical syndrome that may be caused by almost any condition affecting the thorax, abdomen, or internal organs. When a patient presents with chest pain in the emergency room, the first priority is to consider life-threatening causes such as acute coronary syndromes, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism (PE), ruptured aortic aneurysm, and tension pneumothorax [7]. The diagnostic work up for these etiologies bear a rightful demand on time of the emergency room physicians and other resources. On occasions this extensive and expensive diagnostic work up can be avoided with awareness of commoner and non-lethal reasons. Absence of knowledge of this entity often confuses clinicians to pursue the alternative diagnoses such as acute abdomen and acute chest syndromes including pleurisy and coronary syndromes. We report a case of a woman with Bornholm disease secondary to Coxsackievirus B5 (CB5) infection and supplementary review of literature till date.

2. Case

A 68-year-old female was admitted to the hospital with acute onset and progressively worsening sharp epigastric and left sided “gripping” chest pain of severe intensity without any radiation or change in character with position, two days prior to the presentation. The onset was without any trauma. Her past medical history was remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia and hypothyroidism. Her medications included aspirin, amlodipine, lovastatin and levothyroxine. Patient described her pain as pleuritic in nature with exacerbation on taking a deep breath and no position relieved the pain. Patient denied any recent travel. There were no family members with similar symptomatology. On examination, patient was in significant discomfort and clutching pain in the left side of chest and epigastrium. She had normal blood pressure but was mildly tachycardic with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. She had a low grade temperature of 99.9 degree Fahrenheit. Her oxygen saturation was 97% without any supplemental oxygen. The pain was not reproducible on palpation and there was no visible rash. Upon auscultation of the chest there was appreciable pleural rub on the left, and the right lung examination was unremarkable. Rest of her systemic examination was unremarkable. Patient was given appropriate analgesia.

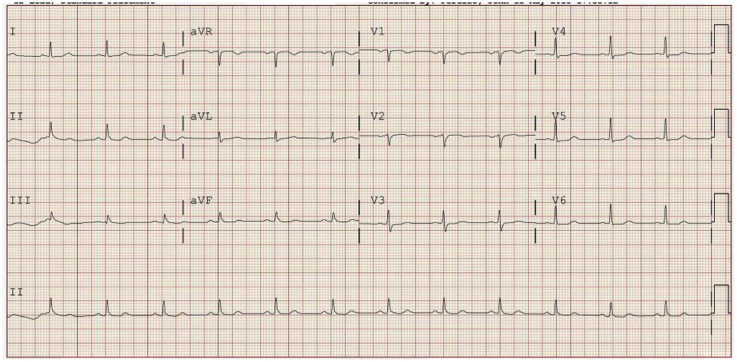

Laboratory data showed normal white blood cell count of 9.4 × 1000/μL (3.4–11.0 × 1000/μL) with 54% neutrophils, along with normal hemoglobin and hematocrit. Serum chemistry was normal with creatinine of 0.75 mg/dL (0.5–1.5 mg/dL) and normal liver function tests. Due to concerns of chest pain and acute coronary syndrome her cardiac biomarkers were checked and troponin T was found to be normal (less than 0.030 ng/mL) on three occasions, each 6 hours apart. Creatine kinase (CK) was normal 122 U/L (24–173 U/L). MB component of CK was found to be normal as well at 3.7 ng/mL (0.0–5.3 ng/mL). EKG done for the patient to rule out any ongoing cardiac ischemia was normal (Fig. 1) without any st wave changes.

Fig. 1.

EKG showing normal sinus rhythm with no ST-T wave changes suggestive of any ischemia.

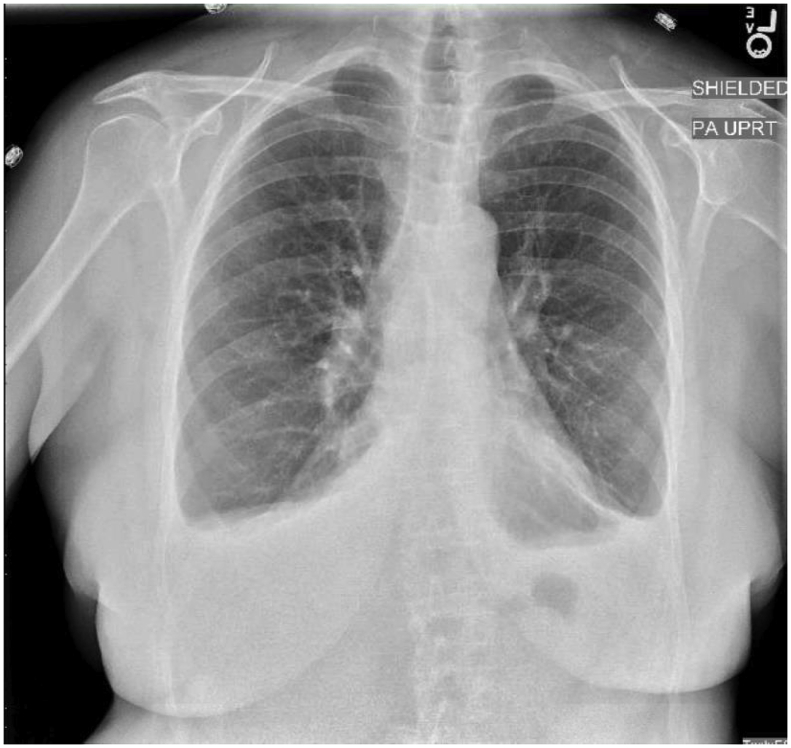

Chest x-ray done showed small bilateral effusions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Chest radiograph showing small bilateral pleural effusions with no airspace disease.

Due to unclear diagnosis of pleuritic chest pain at this time and sinus tachycardia, patient underwent computed tomography (CT) of the chest to rule out pulmonary embolism and was found to be negative for any embolic event or pulmonary infarction, aortic abnormality and gastro-esophageal abnormality. In addition there was no muscular edema noted on the scan. After ruling out the most ominous causes of chest pain, patient was still symptomatic. Now suspicion was high for rare causes of chest pain. Wider net was now casted for vasculitic disorders and rare infections causing similar symptomatology. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were elevated to 65 mm/hr (2–15 mm/hr) and 17.2 mm/hr (0.0–4.9 mg/L) respectively. Her complement levels for C3 were 161 mg/dL (82–167 mg/dL) and for C4 were 16 mg/dL (14–44 mg/dL). Her C-ANCA and p-ANCA panel was negative. Antinuclear antibodies were negative. Further serological testing was done and she was found to have negative serology for coxsackievirus A types 7, 9, 16 and 24. Finally serology returned positive for coxsackievirus B type 5 (CB5) by complement fixation reaction (CFR, Virion/Serion, Clindia Benelux b.v., Almere, the Netherlands) and negative for coxsackievirus B types 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6.

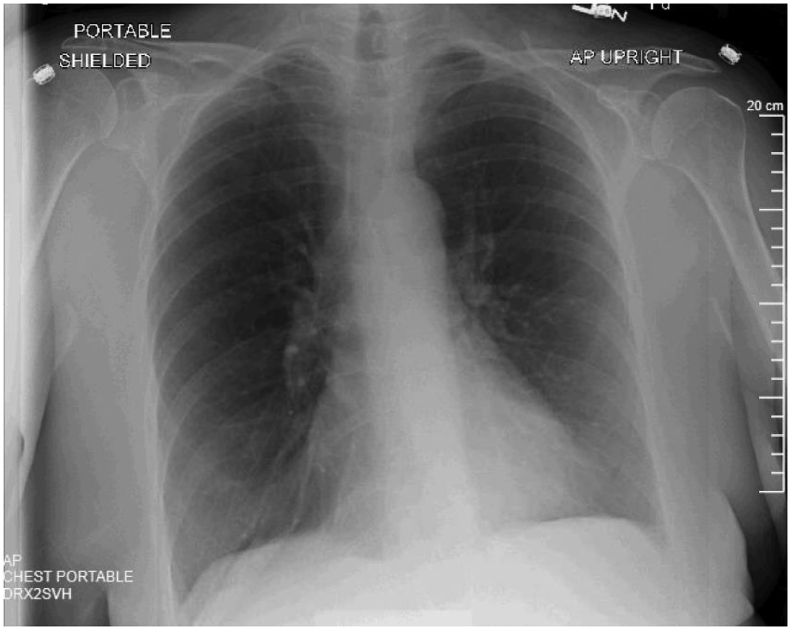

Patient was now continued to be treated as epidemic pleurodynia or Bornholm disease (caused by CB5) with symptom control using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and intravenous fluids. Patient's pain improved significantly over the next 48 hours with resolution of fever and tachycardia. Patient was discharged home on the fourth day with complete resolution of symptoms. At 2 weeks follow up, patient was completely chest pain free. Repeated chest x-ray at this time showed normal lung fields with clearance of bilateral small pleural effusions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Chest radiograph repeated after 2 weeks showing complete resolution of pleural effusions.

3. Discussion

First described in Daae and Homann in Norway, disease has been known with many forenames such as Bornholm (City in Denmark) disease, Devil's grippe, epidemic myalgia and epidemic pleurodynia [8]. However in the early years there was no identifiable pathogen associated with the disease. Since then there have been glaring advances in microbiological and virological sciences. It was not until 1949 when the Coxsackie virus was thought to be associated with epidemic pleurodynia [9,10]. Ever since multiple studies have described the association of Bornholm disease with Coxsackievirus B (CBV) and less frequently echovirus types 1, 6, 8, 9 and 19 and further less frequently with coxsackievirus A (CAV) types 4, 6, 9 and 10 [11,12]. Typical presentation with excruciating pleuritic chest pain or epigastric pain, fevers and complete recovery with supportive care is the norm [8,11,[13], [14], [15]]. Characteristic positive history with negative objective findings makes this malady easily distinguishable. Over the years the disease has been reported in conjunction with various strains of CBV. Data on association of epidemic pleurodynia with coxsackievirus B5 (CB5) is scanty. Bain et al., in 1961, for the first time described epidemic pleurodynia, benign pericarditis and aseptic meningitis which was attributable to CB5 [16]. In general, respiratory complaints are more common with type B virus infections as compared to type A viral strains. Also coxsackievirus type B strains result is more number of hospitalizations [14]. Extensive review of literature is provided in the following table with significant studies and reports (in English) till date (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comprehensive Review of Literature.

| Title | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Pleurodynia caused by an echovirus 1 brought back from the tropics [11] | Leendertse et al. | 2013 |

| Bornholm disease--a pediatric clinical entity that can alert a thoracic surgeon [17] | Tagarakis et al. | 2011 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia caused by coxsackievirus B3 at a medical center in northern Taiwan [10] | Huang et al. | 2010 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease) outbreak in Singapore. A clinical and virological study [18] | Chong et al. | 1975 |

| Association of Group B Coxsackieviruses with Cases of Pericarditis, Myocarditis, or Pleurodynia by Demonstration of Immunoglobulin M Antibody [19] | Schmidt et al. | 1973 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia in Aden associated with infection by echovirus type 1 [12] | McCracken at al. | 1969 |

| The occurrence of Bamble Disease (epidemic pleurodynia) in Norway [20] | Vogelsang | 1967 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia, orchitis, and myocarditis in an adult due to Coxsackie virus, group B, type 4 [21] | Swann | 1961 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease) due to Coxsackie B-5 virus. The inter-relationship of pleurodynia, benign pericarditis and aseptic meningitis [16] | Bain et al. | 1961 |

| A case of epidemic pleurodynia or Bornholm disease [22] | Hale and Pillai | 1956 |

| Studies on the etiology of Bornholm disease (epidemic pleurodynia). II. Epidemiological observations [23] | Johnsson | 1954 |

| Oxford epidemic of Bornholm disease [24] | Warin et al. | 1951 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia with special reference to the differential diagnosis in acute abdominal pain [25] | Ekman | 1953 |

| Isolation of Coxsackie virus from patients with epidemic pleurodynia [26] | Thordarson et al. | 1953 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia in Texas; a study of 22 cases [8] | Huebner et al. | 1953 |

| Bornholm disease in children [27] | Disney et al. | 1953 |

| Studies on the etiology of epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease). I. Clinical and virological observations [28] | Gabinus et al. | 1952 |

| The importance of Coxsackie viruses in human disease, particularly herpangina and epidemic pleurodynia [13] | Huebner et al. | 1952 |

| An outbreak of epidemic pleurodynia, with special reference to the laboratory diagnosis of Coxsackie virus infections [29] | Lazarus et al. | 1952 |

| A virus isolated from a case resembling epidemic pleurodynia; a preliminary report [30] | Howes | 1951 |

| Epidemic myalgia in Cape Town; pleurodynia or Bornholm disease [15] | Prisman and Shrand | 1950 |

| Coxsackie viruses and Bornholm disease [31] | Findlay and Howard | 1950 |

| The etiology of epidemic pleurodynia: a study of two viruses isolated from a typical outbreak [32] | Weller et al. | 1950 |

| Epidemic pleurodynia; clinical and etiologic studies based on 114 cases [33] | Finn et al. | 1949 |

| Acute benign dry pleurisy in the Middle East [34] | Scadding | 1946 |

Classically, commonest strains causing epidemic pleurodynia have been Coxsackievirus B3 and Coxsackievirus A9 and the disease presentation is almost indistinguishable [18]. The group B viruses have been implicated in a multiplicity of presentations, ranging from epidemic pleurodynia (as in our case), aseptic meningitis, pericarditis, orchitis and even as convulsions in infants [16,21]. CB5 in particular have been notoriously associated with myocarditis and pericarditis [35]. There have been large case series described in pediatric populations with proteiform appearances [16,18].

Most cases require admission to the hospital due to non-diagnostic work up in the outpatient settings and it further flummoxes the physician with non-focal examination without any objective physical findings. Careful history often reveals high attack rate amongst the close contacts and family members [15,16,23]. Fever is the commonest presentation, reported in almost 70% of the subjects and the typical “devil's grip” or thoracic stitch is present in about 40% of the cases [23]. However absence of the typical pattern of the same in our patient, at the time of presentation, points to the fact that physicians need to be aware of this variations in presentation. Soft physical findings may include pleural or pericardial rub, which although maybe nonspecific but when taken in context can be an ancillary finding supporting the diagnosis as seen in our case [16,34]. Duration of chest pain may last up to 4 days and duration of pain correlates well with duration of fever [18]. Laboratory data other than specific virological studies is usually not helpful. Patient may have elevated sedimentation rate similar to our patient, but this is found to be non-specific [18]. Cases where myocardium or pericardium is involved, it may present with nonspecific EKG changes such as T wave inversion that resolve with resolution of the disease [21]. In some case series pulmonary infiltrates with or without pleural effusions have been found to be a consistent feature in about half the cases [10].

Underlying mechanism for the phenotypical presentation of epidemic pleurodynia are postulated to be secondary to local viral proliferation in the muscles of chest wall, diaphragm and abdominal muscles. The most likely port of entry is pharynx, proliferation of virus takes place in lymphatic tissues and reaches muscle by blood stream [18,36]. Lepine et al. first described the muscle involvement with the virus and associated inflammatory lesions with isolation of virus from the muscle tissue [37]. Despite its association with muscle instead of pleura or peritoneum, only minority of cases have revealed elevated levels of serum aspartate aminotransferase or creatinine kinase [10,16,27]. Complete recovery is usually the norm, however rare complications may include disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, myocarditis, respiratory failure, and hepatic necrosis with coagulopathy [14]. Symptomatic and expectant management usually suffices, intercostal 2% Xylocaine injections diluted in normal saline have also been tried with success in some cases [17]. This case is being reported, as our patient did not have the classical presence of fever, and paroxysms of pain attack, instead she had persistence of the sharp pain. However characteristic, location, palpatory reproducibility of her pain was typical. She also had localized tenderness on palpation, pleural rub and pleural effusion.

Importance of recognizing this disease in not merely an academic pursuit. According to a CDC report, in 2016 CB4 claimed for 1.9% of all enterovirus infections charting at least 54 cases all over the United States [38]. The differential diagnosis for fever and chest pain or abdominal pain includes serious illnesses such as acute appendicitis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, pulmonary embolism and acute coronary syndromes amongst many others. Some of these can be lethal if not diagnosed with time. Awareness of this entity and inclusion in the differential diagnoses, can avoid the pitfall of surgical intervention at times. Moreover, an understanding of the disease and its natural course can avoid unnecessary and expensive investigations. Knowledge of its viral agent will also avoid unwarranted use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Lastly it will significantly allay the fear and anxiety of the patients and even the doctor of a serious condition due to its self-limiting course and complete recovery in large majority.

Authors' contribution

AL: Conception of study + Manuscript draft + Data collection + Review.

JA: Image Selection + Data collection + Critical Review.

SI: Image Selection + Data collection + Critical review.

AKM: Image Selection + Data collection + Critical Review.

MSK: Manuscript draft + Critical Review.

MN: Conception of study + Manuscript draft + Critical Review.

GMA: Manuscript draft + Critical Review + Expert Opinion.

Conflict of interest

Authors claim no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work required no external funding.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.10.005.

Contributor Information

Amos Lal, Email: Amos.Lal@stvincenthospital.com.

Jamal Akhtar, Email: drfarrukhjamal79@gmail.com.

Sangeetha Isaac, Email: sangeethapisaac@gmail.com.

Ajay Kumar Mishra, Email: Ajay.Mishra@stvincenthospital.com.

Mohammad Saud Khan, Email: mkhan5@lifespan.org.

Mohsen Noreldin, Email: fmnoreldin@gmail.com.

George M. Abraham, Email: George.Abraham@stvincenthospital.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chun J.H., Kim T.H., Han M.Y., Kim N.Y., Yoon K.L. Analysis of clinical characteristics and causes of chest pain in children and adolescents. Kor. J. Pediatr. 2015;58(11):440–445. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.11.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geyser M., Smith S. Chest pain prevalence, causes, and disposition in the emergency department of a regional hospital in Pretoria. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Fam. Med. 2016;8(1):e1–5. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haasenritter J., Biroga T., Keunecke C., Becker A., Donner-Banzhoff N., Dornieden K. Causes of chest pain in primary care--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Croat. Med. J. 2015;56(5):422–430. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieling T. Non-cardiac chest pain. Visceral Med. 2018;34(2):92–96. doi: 10.1159/000486440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim Y.J., Shin E.J., Kim N.S., Lee Y.H., Nam E.W. The importance of esophageal and gastric diseases as causes of chest pain. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2015;18(4):261–267. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2015.18.4.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eslick G.D. Classification, natural history, epidemiology, and risk factors of noncardiac chest pain. Disease A Month DM. 2008;54(9):593–603. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jouriles N.J. Atypical chest pain. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 1998;16(4):717–740. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70030-4. v-vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huebner R.J., Risser J.A., Bell J.A., Beeman E.A., Beigelman P.M., Strong J.C. Epidemic pleurodynia in Texas; a study of 22 cases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1953;248(7):267–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195302122480701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curnen E.C., Shaw E.W., Melnick J.L. Disease resembling nonparalytic poliomyelitis associated with a virus pathogenic for infant mice. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1949;141(13):894–901. doi: 10.1001/jama.1949.02910130008003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang W.T., Lee P.I., Chang L.Y., Kao C.L., Huang L.M., Lu C.Y. Epidemic pleurodynia caused by coxsackievirus B3 at a medical center in northern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi. 2010;43(6):515–518. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leendertse M., van Vugt M., Benschop K.S., van Dijk K., Minnaar R.P., van Eijk H.W. Pleurodynia caused by an echovirus 1 brought back from the tropics. J. Clin. Virol. Off. Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 2013;58(2):490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCracken A.W., Wilkie K.M. Epidemic pleurodynia in Aden associated with infection by echovirus type 1. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1969;63(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(69)90071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huebner R.J., Beeman E.A., Cole R.M., Beigelman P.M., Bell J.A. The importance of Coxsackie viruses in human disease, particularly herpangina and epidemic pleurodynia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1952;247(7):249–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195208142470705. contd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee C.J., Huang Y.C., Yang S., Tsao K.C., Chen C.J., Hsieh Y.C. Clinical features of coxsackievirus A4, B3 and B4 infections in children. PloS One. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prisman J., Shrand H. Epidemic myalgia in Cape Town; pleurodynia or Bornholm disease. South Afr. Med. J. Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1950;24(17):309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bain H.W., Mc L.D., Walker S.J. Epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease) due to Coxsackie B-5 virus. The inter-relationship of pleurodynia, benign pericarditis and aseptic meningitis. Pediatrics. 1961;27:889–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tagarakis G.I., Karangelis D., Tsolaki F., Dikoudi M., Koufakis T., Mouzaki K. Bornholm disease--a pediatric clinical entity that can alert a thoracic surgeon. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2011;47(4):242. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong A.Y., Lee L.H., Wong H.B. Epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease) outbreak in Singapore. A clinical and virological study. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1975;27(2):151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt N.J., Magoffin R.L., Lennette E.H. Association of group B coxsackieviruses with cases of pericarditis, myocarditis, or pleurodynia by demonstration of immunoglobulin M antibody. Infect. Immun. 1973;8(3):341–348. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.3.341-348.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogelsang T.M. The occurrence of Bamble Disease (epidemic pleurodynia) in Norway. Med. Hist. 1967;11(1):86–90. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swann N.H. Epidemic pleurodynia, orchitis, and myocarditis in an adult due to Coxsackie virus, group B, type 4. Ann. Intern. Med. 1961;54:1008–1013. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-54-5-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hale J.H., Pillai K. A case of epidemic pleurodynia or Bornholm disease. Med. J. Malaya. 1956;11(2):116–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnsson T. Studies on the etiology of Bornholm disease (epidemic pleurodynia). II. Epidemiological observations. Archiv fur die gesamte Virusforschung. 1954;5(4):401–412. doi: 10.1007/BF01243009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warin J.F., Davies J.B., Sanders F.K., Vizoso A.D. Oxford epidemic of Bornholm disease, 1951. Br. Med. J. 1953;1(4824):1345–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4824.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekman C.A. Epidemic pleurodynia with special reference to the differential diagnosis in acute abdominal pain. Acta Chir. Scand. 1953;106(5):377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thordarson O.T., Sigurdsson B., Grimsson H. Isolation of Coxsackie virus from patients with epidemic pleurodynia. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1953;152(9):814–815. doi: 10.1001/jama.1953.63690090007010d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Disney M.E., Howard E.M., Wood B.S., Findlay G.M. Bornholm disease in children. Br. Med. J. 1953;1(4824):1351–1354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4824.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabinus O., Gard S., Johnsson T., Poldre A. Studies on the etiology of epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease). I. Clinical and virological observations. Archiv fur die gesamte Virusforschung. 1952;5(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01245135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarus A.S., Johnston E.A., Galbraith J.E. An outbreak of epidemic pleurodynia, with special reference to the laboratory diagnosis of Coxsackie virus infections. Am. J. Public Health Nation's Health. 1952;42(1):20–26. doi: 10.2105/ajph.42.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howes D.W. A virus isolated from a case resembling epidemic pleurodynia; a preliminary report. Med. J. Aust. 1951;2(18):597–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Findlay G.M., Howard E.M. Coxsackie viruses and Bornholm disease. Br. Med. J. 1950;1(4664):1233–1236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4664.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weller T.H., Enders J.F., Buckingham M., Finn J.J., Jr. The etiology of epidemic pleurodynia: a study of two viruses isolated from a typical outbreak. J. Immunol. (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 1950;65(3):337–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finn J.J., Jr., Weller T.H., Morgan H.R. Epidemic pleurodynia; clinical and etiologic studies based on 114 cases. Arch. Intern. Med. 1949;83(3):305–321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1949.00220320059005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scadding J.G. Acute benign dry pleurisy in the Middle East. Lancet (London, England) 1946;1(6404):763–767. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(46)91595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaaloul I., Riabi S., Harrath R., Hunter T., Hamda K.B., Ghzala A.B. Coxsackievirus B detection in cases of myocarditis, myopericarditis, pericarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy in hospitalized patients. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;10(6):2811–2818. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chu P.Y., Ke G.M., Chang C.H., Lin J.C., Sun C.Y., Huang W.L. Molecular epidemiology of coxsackie A type 24 variant in Taiwan, 2000-2007. J. Clin. Virol. Off. Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virol. 2009;45(4):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lepine P., Desse G., Sautter V. Muscle biopsy with histological examination and isolation of Coxsackie virus in epidemic myalgia (Bornholm disease) Bulletin de l'Academie nationale de medecine. 1952;136(5–6):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abedi G.R., Watson J.T., Nix W.A., Oberste M.S., Gerber S.I. Enterovirus and parechovirus surveillance - United States, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018;67(18):515–518. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6718a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.