Abstract

BACKGROUND

The effect of procalcitonin-guided use of antibiotics on treatment for suspected lower respiratory tract infection is unclear.

METHODS

In 14 U.S. hospitals with high adherence to quality measures for the treatment of pneumonia, we provided guidance for clinicians about national clinical practice recommendations for the treatment of lower respiratory tract infections and the interpretation of procalcitonin assays. We then randomly assigned patients who presented to the emergency department with a suspected lower respiratory tract infection and for whom the treating physician was uncertain whether antibiotic therapy was indicated to one of two groups: the procalcitonin group, in which the treating clinicians were provided with real-time initial (and serial, if the patient was hospitalized) procalcitonin assay results and an antibiotic use guideline with graded recommendations based on four tiers of procalcitonin levels, or the usual-care group. We hypothesized that within 30 days after enrollment the total antibiotic-days would be lower — and the percentage of patients with adverse outcomes would not be more than 4.5 percentage points higher — in the procalcitonin group than in the usual-care group.

RESULTS

A total of 1656 patients were included in the final analysis cohort (826 randomly assigned to the procalcitonin group and 830 to the usual-care group), of whom 782 (47.2%) were hospitalized and 984 (59.4%) received antibiotics within 30 days. The treating clinician received procalcitonin assay results for 792 of 826 patients (95.9%) in the procalcitonin group (median time from sample collection to assay result, 77 minutes) and for 18 of 830 patients (2.2%) in the usual-care group. In both groups, the procalcitonin-level tier was associated with the decision to prescribe antibiotics in the emergency department. There was no significant difference between the procalcitonin group and the usual-care group in antibiotic-days (mean, 4.2 and 4.3 days, respectively; difference, −0.05 day; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.6 to 0.5; P = 0.87) or the proportion of patients with adverse outcomes (11.7% [96 patients] and 13.1% [109 patients]; difference, −1.5 percentage points; 95% CI, −4.6 to 1.7; P<0.001 for noninferiority) within 30 days.

CONCLUSIONS

The provision of procalcitonin assay results, along with instructions on their interpretation, to emergency department and hospital-based clinicians did not result in less use of antibiotics than did usual care among patients with suspected lower respiratory tract infection. (Funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences; ProACT ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02130986.)

The overuse of antibiotic agents is a public health problem1 associated with increased health care costs and antibiotic resistance.2 Overuse of antibiotics is common in infections of the lower respiratory tract, where bacterial and viral infections manifest similarly.3–5 Procalcitonin is a peptide with levels that are more typically elevated in bacterial than in viral infections6,7; the magnitude of the elevation correlates with the severity of infection,8,9 and decreasing levels over time correlate with the resolution of infection.10 Several European trials have tested whether procalcitonin assay results, folded into an antibiotic prescription guideline, curbed the use of antibiotics in suspected lower respiratory tract infection.11–14 These trials showed that procalcitonin-based guidance reduced the use of antibiotics with no apparent harm, and in February 2017, on the basis of a meta-analysis of these and other trials, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a procalcitonin assay to help guide the starting or stopping of antibiotic treatment in suspected lower respiratory tract infection in the emergency department or hospital.15,16

However, the applicability of these data to routine practice is unclear. In the largest trial, physicians could overrule procalcitonin guideline recommendations only after consulting with the coordinating center, for critical illness, or for legionella infection.11,17 National authorities and medical societies reached varying conclusions about procalcitonin-guided antibiotic prescription in suspected lower respiratory tract infection, ranging from findings of moderate-strength evidence of benefit and low-strength evidence of not causing harm18 to recommendations against routine use.19,20 Few studies were conducted in the United States,21,22 where prescribing patterns may differ from those in Europe. We conducted a multicenter trial to assess whether a procalcitonin antibiotic prescribing guideline, implemented for the treatment of suspected lower respiratory tract infection with reproducible strategies, would result in less exposure to antibiotics than usual care, without a significantly higher rate of adverse events.

Methods

Trial Oversight

We conducted the Procalcitonin Antibiotic Consensus Trial (ProACT), a patient-level, 1:1 randomized trial, in 14 hospitals in the United States. The trial design and rationale have been published previously.23 The University of Pittsburgh and all site institutional review boards approved the protocol, which is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. The National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded the trial and convened an independent data and safety monitoring board (see the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). ProACT was coordinated by the University of Pittsburgh Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness Center and the Multidisciplinary Acute Care Research Organization. Procalcitonin assays and laboratory training were provided by bioMérieux, which had no other role in the trial. The investigators remained unaware of the outcomes in each trial group until data lock in October 2017. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Sites and Patients

The sites were predominantly urban academic hospitals that had a high level of adherence to Joint Commission pneumonia core measures,24 and none used procalcitonin in routine care. We enrolled adult patients (≥18 years old) in the emergency department for whom the treating clinician had given an initial diagnosis of acute lower respiratory tract infection (<28 days in duration) but had not yet decided to give or withhold antibiotics and about whom there was uncertainty regarding the need for antibiotics, such that procalcitonin data could influence the prescribing decision. Using baseline characteristics and published criteria, we categorized the initial diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infection into final diagnoses of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma exacerbation, acute bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, and other.11,13,25–31 The definitions and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, and full details of the trial are provided in the protocol and statistical analysis plan. All the patients or their authorized representatives provided written informed consent.

Trial Interventions

In both treatment groups, clinicians retained autonomy regarding care decisions. We disseminated national antibiotic guidelines for lower respiratory tract infection and the procalcitonin antibiotic prescribing guideline (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix) in all promotional tools and training meetings.

In the procalcitonin group, the intervention consisted of measuring and reporting the procalcitonin assay results and providing the procalcitonin guideline to aid the treating clinicians in their interpretation of the results. We measured procalcitonin using a rapid assay with an analytic range of 0.05 to 200 μg per liter (VIDAS B.R.A.H.M.S Procalcitonin, bioMérieux). The guideline used the same cutoff values as had been used previously and approved by the FDA (i.e., with antibiotics strongly discouraged for procalcitonin levels <0.1 μg per liter, discouraged for levels 0.1 to 0.25 μg per liter, recommended for levels >0.25 to 0.5 μg per liter, and strongly recommended for levels >0.5 μg per liter). We obtained blood samples for procalcitonin measurement in the emergency department, and if the patient was hospitalized, 6 to 24 hours later and on days 3, 5, and 7, if the patient was still in the hospital and receiving antibiotics.

We used a multifaceted implementation approach to mimic how a hospital might typically deploy quality-improvement measures when introducing a new intervention (see the Supplementary Appendix). Before the launch of the trial, the site principal investigators sent letters to local primary care providers with a synopsis of the trial. We promoted the rapid delivery of information about procalcitonin to the treating clinicians by tracking delivery times, providing feedback to sites, coordinating the collection of blood samples for the trial with routine morning draws, and embedding the results and guideline into the sites’ electronic health records when feasible (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). If antibiotics were administered when the procalcitonin level was 0.25 μg per liter or lower, the site coordinator queried the treating clinician and recorded the reasons for nonadherence; the coordinators did not ask the clinicians any other questions. We reviewed all cases of nonadherence with the site principal investigators. On discharge, we provided patients with a letter for their primary care provider that included their last procalcitonin assay result, a synopsis of the trial, and the procalcitonin guideline.

In the usual-care group, we drew blood at enrollment for procalcitonin measurement using the same assay, but the results were clinically unavailable. Trial personnel had no bedside role other than the collection of data and blood samples.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was total antibiotic exposure, defined as the total number of antibiotic-days within 30 days after enrollment. We defined an antibiotic-day as any day on which a participant received any oral or intravenous antibacterial agent. Our primary safety outcome was a composite of adverse outcomes that could be attributable to withholding antibiotics in lower respiratory tract infection, within 30 days after enrollment (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Secondary outcomes included prescription of antibiotics in the emergency department, antibiotic receipt by day 30, antibiotic-days during the hospital stay (among patients who were admitted), admission to the intensive care unit, subsequent emergency department visits by day 30, and quality of life as assessed with the Airway Questionnaire 20.32 We obtained data through chart review performed by site research staff and by telephone calls at days 15 and 30 made by coordinating center staff who were unaware of the treatment-group assignments. We collected data on serious adverse events in accordance with federal guidelines.33

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed all data according to the intentionto-treat principle. We used multiple imputations with chained equations for missing outcome data, combined with the use of Rubin’s method.34 For the primary outcome, we hypothesized that procalcitonin-guided antibiotic prescription would be superior to usual care and compared the mean number of antibiotic-days between groups using two-sample t-tests. For the primary safety outcome, we hypothesized that procalcitonin-guided antibiotic prescription would be noninferior to usual care, on the basis of a confidence interval based on a normal distribution for the difference in proportions between groups. The primary efficacy and safety outcomes were considered as coprimary in the design, and significant results for both would be required to declare “success” for the intervention. We initially determined that with 1514 patients, the trial would have at least 80% power to both detect a between-group difference of 1 antibiotic-day and to declare noninferiority on the basis of a predefined noninferiority margin of 4.5 percentage points, with an overall alpha of 0.05, two interim analyses, an assumed 11% rate of adverse outcomes in the usual-care group,8,35 and 10% loss to follow-up. At the second interim analysis in April 2017, the loss to follow-up was 18%, and the data and safety monitoring board approved an increase in enrollment to 1664 patients.

In accordance with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) recommendations for noninferiority trials,36 we conducted a per-protocol analysis in which the intervention group was restricted to patients for whom the trial intervention (i.e., measuring and reporting the procalcitonin results and providing the procalcitonin guideline) was achieved at all time points. To explore the effect of the intervention when clinicians consistently followed the procalcitonin guideline, we conducted a per-guideline analysis in which the intervention group was restricted to patients for whom clinicians adhered to guideline recommendations at all time points. The per-protocol analysis had the potential to be affected by selection bias due to inherent differences between cases in which the protocol was fully executed and those in which it was not; this was also true for the perguideline analysis for cases in which the clinician was adherent and those in which the clinician was nonadherent.37 We therefore applied instrumentalvariable estimation to both analyses, using the randomized assignment as the instrument.38,39

We conducted two sensitivity analyses to assess robustness to missing data: a complete-case analysis, under an assumption that data were missing at random, and a missing-not-at-random analysis, in which all missing data were imputed from the usual-care group.40 We conducted prespecified subgroup analyses of final diagnostic category, age, sex, ethnic group, and race. After unblinding of the data, we performed post hoc analyses to gain an understanding of the primary results. We plotted antibiotic prescription in the emergency department, initial presentation and outcomes, and intervention effect according to initial procalcitonin-level tier, as well as antibiotic exposure over time. To adjust for multiple comparisons, we applied a Bonferroni correction and present 99.86% confidence intervals for the 36 secondary antibiotic-exposure comparisons. We conducted the analyses with R Open software, version 3.4.2 (Microsoft), and SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). The complete statistical analysis plan is provided in the protocol.

Results

Patients

From November 2014 through May 2017, a total of 1664 patients were enrolled and underwent randomization; 8 requested withdrawal (4 in each group), leaving a final analysis cohort of 1656 patients (826 in the procalcitonin group and 830 in the usual-care group). A total of 1430 patients (86.4%) completed follow-up: 1345 (81.2%) completed 30-day follow-up, and 85 (5.1%) completed 15-day follow-up only (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics were similar among patients for whom complete 30-day data were available and those with incomplete data (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix), as well as in the two treatment groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up.

A patient could have had more than one reason for exclusion. Mixed modeling was used to impute missing data for the intention-to-treat analysis of the primary outcome. Fifteen patients who were found to be ineligible after enrollment were retained in the intention-to-treat analysis of the primary outcome; the reasons for ineligibility were previous receipt of antibiotics (7 patients), homelessness (2), enrollment in the Procalcitonin Antibiotic Consensus Trial (ProACT) in the past 30 days (1), severe immunosuppression (1), current long-term dialysis (1), metastatic cancer (1), and site logistic issues (2). A total of 27 patients who completed the 30-day follow-up could not recall their use of antibiotics. LAR denotes legally authorized representative.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients.*

| Characteristic | Procalcitonin (N = 826) | Usual Care (N = 830) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 52.9±18.4 | 53.2±18.7 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 357 (43.2) | 354 (42.7) |

| Race or ethnic group† | ||

| White — no. (%) | 455 (55.1) | 470 (56.6) |

| Black — no. (%) | 296 (35.8) | 297 (35.8) |

| Hispanic — no./total no. (%) | 108/815 (13.3) | 104/812 (12.8) |

| Coexisting conditions and risk factors | ||

| Charlson comorbidity score‡ | 1.4±1.6 | 1.4±1.4 |

| Current smoker — no./total no. (%) | 263/804 (32.7) | 256/813 (31.5) |

| COPD — no./total no. (%) | 267/822 (32.5) | 262/823 (31.8) |

| Asthma — no./total no. (%) | 312/822 (38.0) | 337/823 (40.9) |

| Home medications — no./total no. (%)§ | ||

| Home oxygen | 89/820 (10.9) | 87/823 (10.6) |

| Oral glucocorticoids | 107/820 (13.0) | 108/823 (13.1) |

| Inhaled glucocorticoids | 211/820 (25.7) | 225/822 (27.4) |

| Inhaled long-acting bronchodilators | 225/820 (27.4) | 243/822 (29.6) |

| Leukotriene-receptor antagonists | 43/820 (5.2) | 59/823 (7.2) |

| Symptoms | ||

| Duration — days | 5.5±5.1 | 5.5±5.1 |

| Type — no./total no. (%) | ||

| Cough | 734/822 (89.3) | 714/823 (86.8) |

| Dyspnea | 683/822 (83.1) | 715/823 (86.9) |

| Sputum production | 495/822 (60.2) | 443/823 (53.8) |

| Chest discomfort | 423/822 (51.5) | 454/823 (55.2) |

| Chills | 279/822 (33.9) | 256/823 (31.1) |

| Clinical findings¶ | ||

| Temperature — °C | 36.9±0.6 | 36.8±0.6 |

| Heart rate — beats/min | 90.3±17.9 | 91.9±18.5 |

| Respiratory rate — breaths/min | 19.9±5.2 | 20.0±5.8 |

| Arterial pressure — mm Hg | 96.0±15.1 | 96.4±15.0 |

| Oxygen saturation — % | 96.4±4.8 | 96.4±2.9 |

| Rhonchi — no./total no. (%) | 111/822 (13.5) | 117/823 (14.2) |

| Wheezing — no./total no. (%) | 440/822 (53.5) | 456/823 (55.4) |

| Median white-cell count (IQR) — cells/mm3 ‖ | 8.8 (6.8–11.4) | 8.9 (6.8–12.1) |

| Procalcitonin level** | ||

| Median level (IQR) — μg/liter | 0.05 (0.05–0.10) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| Category — no./total no. (%) | ||

| <0.1 μg/liter | 588/808 (72.8) | 648/788 (82.2) |

| 0.1–0.25 μg/liter | 158/808 (19.6) | 72/788 (9.1) |

| >0.25–0.5 μg/liter | 27/808 (3.3) | 23/788 (2.9) |

| >0.5 μg/liter | 35/808 (4.3) | 45/788 (5.7) |

| Final diagnosis — no./total no. (%)†† | ||

| Asthma | 310/822 (37.7) | 336/823 (40.8) |

| COPD | 265/822 (32.2) | 259/823 (31.5) |

| Acute bronchitis | 208/822 (25.3) | 190/823 (23.1) |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 167/822 (20.3) | 161/823 (19.6) |

| PSI class I | 48/167 (28.7) | 34/161 (21.1) |

| PSI class II | 52/167 (31.1) | 52/161 (32.3) |

| PSI class III | 30/167 (18.0) | 33/161 (20.5) |

| PSI class IV | 29/167 (17.4) | 38/161 (23.6) |

| PSI class V | 7/167 (4.2) | 3/161 (1.9) |

| Other lower respiratory tract infection | 42/822 (5.1) | 42/823 (5.1) |

| Non–lower respiratory tract infection | 20/822 (2.4) | 21/823 (2.6) |

| Hospitalized — no. (%)‡‡ | 378 (45.8) | 404 (48.7) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant between-group differences in baseline characteristics, with the exception of dyspnea (P = 0.04), sputum production (P = 0.01), and procalcitonin (P<0.001). COPD denotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and IQR interquartile range.

Race and ethnic group were reported by the patients.

The Charlson comorbidity score41 is a measure of the effect of coexisting conditions on mortality and ranges from 0 to 33, with higher scores indicating a greater burden of illness. Information on the score was missing for 16 patients (6 in the procalcitonin group and 10 in the usual-care group).

Home medications were defined as medications taken by the patient in previous 7 days.

Data on these measures were missing for 11 patients (4 in the procalcitonin group and 7 in the usual-care group), with the exception of temperature (data missing for 34 patients [19 in the procalcitonin group and 15 in the usualcare group]), respiratory rate (13 patients [5 and 8]), and oxygen saturation (12 patients [5 and 7]).

Data on the white-cell count were missing for 456 patients (237 in the procalcitonin group and 219 in the usual-care group).

Data on the procalcitonin level were missing for 60 patients (18 in the procalcitonin group and 42 in the usual-care group).

A patient could have more than one final diagnosis: 215 patients (108 in the procalcitonin group and 107 in the usual-care group) had asthma and COPD, 109 patients (57 and 52) had community-acquired pneumonia and COPD, and 89 patients (44 and 45) had community-acquired pneumonia and asthma. The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) is a clinical severity score for community-acquired pneumonia; higher PSI classes are predictive of higher morbidity and mortality.

This category includes 8 patients who had a length of stay in the emergency department of more than 2 days.

Final diagnoses, which were available for 1645 of the patients, included asthma exacerbation (646 patients, 39.3%), acute exacerbation of COPD (524, 31.9%), acute bronchitis (398, 24.2%), and community-acquired pneumonia (328, 19.9%). The initial procalcitonin level, available for 1596 patients, was less than 0.1 μg per liter in 1236 (77.4%), 0.1 to 0.25 μg per liter in 230 (14.4%), more than 0.25 to 0.5 μg per liter in 50 (3.1%), and more than 0.5 μg per liter in 80 (5.0%). A total of 782 patients (47.2%) were hospitalized, 604 (36.5%) received antibiotics in the emergency department, and 984 (59.4%) received antibiotics within 30 days. The initial procalcitonin-level tier was associated with the presence of systematic inflammatory response criteria and with the clinician’s estimation, based on clinical features only, that the cause of illness was bacterial (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Protocol Adherence

In the emergency department, procalcitonin assay results were obtained and reported to the treating clinician for 792 of 826 patients (95.9%) assigned to the procalcitonin group (median time from sample collection to assay result, 77 minutes). For 18 of 826 patients (2.2%), a blood sample was not obtained, and 16 patients (1.9%) left the emergency department before the results could be reported. For the entire protocol period, 696 patients (84.3%) had all procalcitonin results obtained and reported at all time points, 67 (8.1%) had all but one, 20 (2.4%) had all but two, and 9 (1.1%) had more than two missing results. In the usual-care group, 18 of 830 patients (2.2%) underwent procalcitonin testing as part of clinical care.

Procalcitonin Guideline Adherence

In the emergency department, clinicians adhered to the procalcitonin guideline recommendation for 577 of 792 patients (72.9%) in the procalcitonin group for whom results were obtained and reported. For the entire protocol period, clinicians adhered to all procalcitonin guideline recommendations at all time points for 513 of 792 patients (64.8%) (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Adherence to the guideline among clinicians was stable throughout the trial (rate of complete guideline adherence for each third of the trial period, 66.8%, 59.8%, and 67.8%; P = 0.11) and varied according to final diagnosis (asthma exacerbation, 64.2%; acute exacerbation of COPD, 49.2%; acute bronchitis, 82.4%; and community-acquired pneumonia, 39.4%). In an analysis of the 466 time points at which antibiotics were prescribed despite low procalcitonin levels, the most common reasons were clinician belief that a bacterial infection was present (183 time points, 39.3%), clinician belief that the patient had an acute COPD exacerbation requiring antibiotics (158 time points, 33.9%), and prescription occurring before the procalcitonin result was available (92 time points, 19.7%).

Outcomes

In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was no significant difference in antibiotic exposure during the first 30 days between the procalcitonin group and the usual-care group (mean antibiotic-days, 4.2 and 4.3 days, respectively; difference, −0.05 day; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.6 to 0.5; P = 0.87) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The results were similar in the per-protocol analysis (difference, −0.1 day; 95% CI, −0.7 to 0.6), per-guideline analysis (−0.1 day; 95% CI, −1.0 to 0.8), complete-case analysis (−0.1 day; 95% CI, −0.7 to 0.5), and missing-not-at-random analysis (−0.1 day; 95% CI, −0.7 to 0.5). There was no significant difference in antibiotic-days by day 30 in any prespecified subgroup analysis (Table 2, and Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 2. Antibiotic-Days by Day 30 after Enrollment.

Violin plots for the primary outcome of antibiotic-days by day 30 are shown. The width of the colored shape indicates the probability density of patients with a given result. The gray notched box plots represent the median (yellow horizontal line), 95% confidence interval of the median (notch), interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile) (box), and the upper 1.5 times the interquartile range (solid vertical line).

Table 2.

Antibiotic Exposure.*

| Outcome | Procalcitonin (N = 826) | Usual Care (N = 830) | Difference (95% or 99.86% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat population‡ | |||

| Antibiotic-days by day 30§ | 4.2±5.8 | 4.3±5.6 | −0.05 (−0.6 to 0.5) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no. (%)¶ | 471 (57.0) | 513 (61.8) | −4.8 (−12.7 to 3.0) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no. (%)¶‖ | 282 (34.1) | 321 (38.7) | −4.6 (−12.2 to 3.0) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 2.6±3.3 | 2.7±3.0 | −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 5.0±4.4 | 4.7±3.5 | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.9) |

| Per-protocol population** | |||

| No. of patients | 696 | 830 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 4.2±5.7 | 4.3±5.7 | −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.6) |

| Per-guideline population†† | |||

| No. of patients | 513 | 830 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 4.2±5.7 | 4.3±5.7 | −0.1 (−1.0 to 0.8) |

| Complete-case population‡‡ | |||

| No. of patients | 658 | 645 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 4.5±5.8 | 4.6±5.7 | −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.5) |

| Missing-not-at-random population‡‡ | |||

| No. of patients | 826 | 830 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30§ | 4.3±5.8 | 4.4±5.7 | −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.5) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of asthma | |||

| No. of patients | 310 | 336 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 3.7±5.2 | 3.6±4.9 | 0.1 (−1.2 to 1.4) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 169/310 (54.6) | 182/336 (54.1) | 0.5 (−12.3 to 13.3) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 90/310 (28.9) | 104/336 (30.8) | −1.9 (−13.5 to 9.6) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 1.8±2.4 | 2.3±2.9 | −0.4 (−1.4 to 0.6) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 4.0±3.0 | 4.2±3.0 | −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of COPD | |||

| No. of patients | 265 | 259 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 5.3±6.1 | 5.2±5.3 | 0.1 (−1.6 to 1.7) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 191/265 (71.9) | 200/259 (77.4) | −5.5 (−17.7 to 6.8) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 108/265 (40.6) | 115/259 (44.3) | −3.7 (−17.5 to 10.1) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 3.0±3.9 | 2.8±2.4 | 0.2 (−0.8 to 1.3) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 5.4±4.8 | 4.6±3.1 | 0.8 (−0.0 to 1.6) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of acute bronchitis | |||

| No. of patients | 208 | 190 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 2.7±5.1 | 3.6±5.5 | −0.9 (−2.6 to 0.9) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 77/208 (37.0) | 100/190 (52.8) | −15.8 (−31.9 to 0.4) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 36/208 (17.3) | 61/190 (32.1) | −14.8 (−28.5 to −1.1) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 1.6±2.3 | 1.9±3.4 | −0.3 (−2.1 to 1.6) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 5.4±5.7 | 4.4±3.8 | 1.0 (−0.9 to 3.0) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia | |||

| No. of patients | 167 | 161 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 7.8±7.0 | 7.2±6.0 | 0.7 (−1.7 to 3.1) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 148/167 (88.6) | 154/161 (95.9) | −7.3 (−16.8 to 2.2) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 120/167 (71.9) | 123/161 (76.3) | −4.4 (−19.9 to 11.0) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 3.9±3.0 | 4.1±3.1 | −0.2 (−1.5 to 1.1) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 5.8±4.9 | 5.9±4.2 | −0.1 (−1.2 to 1.1) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of other lower respiratory tract infection | |||

| No. of patients | 42 | 42 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 2.5±4.4 | 4.4±6.4 | −2.0 (−4.4 to 0.5) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 17/42 (39.6) | 24/42 (56.9) | −17.4 (−39.2 to 4.5) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 11/42 (26.2) | 18/42 (42.4) | −16.2 (−36.3 to 3.9) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 1.0±2.0 | 2.2±2.3 | −1.2 (−2.6 to 0.3) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 5.0±4.0 | 5.7±2.6 | −0.6 (−2.9 to 1.6) |

| Patients with final diagnosis of non–lower respiratory tract infection | |||

| No. of patients | 20 | 21 | |

| Antibiotic-days by day 30 | 2.1±3.2 | 1.4±2.8 | 0.7 (−1.3 to 2.6) |

| Received any antibiotics by day 30 — estimated no./total no. (%)¶ | 7/20 (37.2) | 6/20 (30.2) | 7.0 (−23.1 to 37.2) |

| Antibiotic prescription in ED — estimated no./total no. (%)¶‖ | 3/20 (15.0) | 5/21 (23.8) | −8.8 (−32.8 to 15.2) |

| Antibiotic-days during hospital stay | 2.6±3.0 | 0.8±1.5 | 1.9 (−1.4 to 5.1) |

| Hospital length of stay — days | 6.0±3.8 | 2.8±1.0 | 3.3 (−0.6 to 7.1) |

All data were analyzed in accordance with the intention-to-treat principle, and multiple imputation with the use of chained equations was used for missing outcome data. Plus–minus values are means ±SD.

To adjust for multiple comparisons, 99.86% confidence intervals are provided for the secondary antibiotic-exposure outcomes (i.e., received any antibiotics by day 30, antibiotic prescription in the emergency department [ED], and antibiotic-days during hospital stay) in the intention-to-treat population and for all antibiotic-exposure outcomes for the four main final diagnoses (asthma, COPD, acute bronchitis, and community-acquired pneumonia). For outcomes expressed as percentages, the differences are given in percentage points.

The intention-to-treat population included all patients who underwent randomization and were eligible for the analysis.

The mean (±SD) number of antibiotic-days by day 30 among survivors at day 30 (1630 patients) was 4.3±5.7; the mean number of antibiotic-days by day 30 among nonsurvivors at day 30 (26 patients) was 4.4±4.3.

For the outcomes of received any antibiotics by day 30 and antibiotic prescription in ED, we first generated proportions from the intention-to-treat statistical model. We then multiplied these proportions by the sample size in each treatment group to estimate the counts, rounded to the nearest integer.

Antibiotic prescription in the ED includes post-randomization receipt of antibiotics in ED and provision of an antibiotic prescription for patients at the time of discharge from the ED.

The procalcitonin group in the per-protocol population included only the patients for whom the trial intervention was completed at all time points.

The procalcitonin group in the per-guideline population included only the patients for whom the treating clinician adhered to procalcitonin guideline recommendations at all time points.

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess robustness to missing data: a complete-case analysis, under an assumption that data were missing at random, and a missing-not-at-random analysis, in which all data were imputed from the usual-care group.

By 30 days, 96 patients in the procalcitonin group (11.7%) and 109 patients in the usual-care group (13.1%) had incurred a safety outcome event in the intention-to-treat analysis; the 95% confidence interval for the −1.5-percentage-point difference in risk (−4.6 to 1.7) excluded the prespecified noninferiority margin of 4.5 percentage points (P<0.001 for noninferiority) (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). The results were similar in the per-protocol, per-guideline, complete-case, and missing-not-at-random analyses, as well as across the prespecified subgroups.

In the analysis of secondary outcomes, there was no significant difference between the procalcitonin group and the usual-care group in the percentage of patients receiving any antibiotics within 30 days (57.0% and 61.8%, respectively; risk difference, −4.8 percentage points; 99.86% CI, −12.7 to 3.0), the percentage of patients receiving an antibiotic prescription in the emergency department (34.1% and 38.7%; risk difference, −4.6 percentage points; 99.86% CI, −12.2 to 3.0), or the mean hospital antibiotic-days among hospitalized patients (2.6 and 2.7 days; risk difference −0.1; 99.86% CI, −0.8 to 0.6) (Table 2). However, for acute bronchitis, the proportion of patients receiving an antibiotic prescription in the emergency department was lower in the procalcitonin group than in the usual-care group (17.3% vs. 32.1%; risk difference, −14.8 percentage points; 99.86% CI, −28.5 to −1.1).

For the incidence of individual outcomes of the composite safety outcome, admission to the intensive care unit, and subsequent emergency department visits, the 95% confidence interval of the differences in risk between the groups excluded the prespecified noninferiority margin of 4.5 percentage points, with upper limits ranging from 0.1 to 3.9 percentage points (Tables S5 and S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). The rates of death and organ failure were low in both groups, ranging from 0.5% to 2.6%. Hospital readmission was the most common individual adverse outcome and accounted for 132 of 205 adverse outcomes (64.4%); the rates were similar in the two treatment groups (7.6% in the procalcitonin group and 8.5% in the usual-care group). There was also no significant difference in quality of life between the groups. The rate of serious adverse events did not differ between the groups, and none of the events were judged by the site principal investigator as being related to the trial. Additional details are provided in Tables S5, S6, and S7 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Post hoc analyses showed a possible interaction between treatment group and initial procalcitonin-level tier (P = 0.02 for the interaction term). Although the observed rates of antibiotic exposure were lower in the procalcitonin group than in the usual-care group among patients in the second procalcitonin-level tier (i.e., 0.1 to 0.25 μg per liter) (Table S8 and Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix) and in the combined emergency department and hospital period, these differences were not significant (Fig. 3). A total of 82.6% of patients in the trial population presented in the lowest and highest procalcitonin tiers, which are accompanied by the strongest recommendations, yet the rates of antibiotic prescription were similar in the two groups (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, in both treatment groups, the rate of prescription of antibiotics increased with procalcitonin-level tier (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

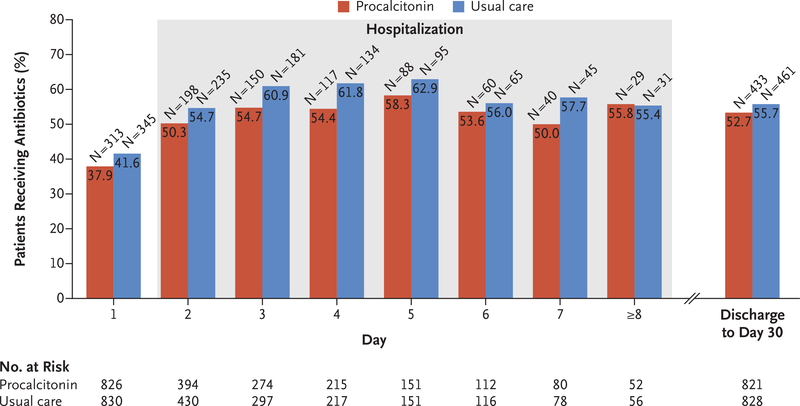

Figure 3. Antibiotic Exposure over Time.

Day 1 is from the time of enrollment to midnight. Day 2 and beyond are from midnight to midnight. Serial procalcitonin levels were obtained from hospitalized patients through day 7. Data on post-discharge antibiotic exposure were derived from the intention-to-treat analysis of the primary outcome.

Discussion

In this multicenter trial, the use of a procalcitonin-guided antibiotic prescription guideline did not result in less exposure to antibiotics than did usual care among patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected lower respiratory tract infection. There are several possible explanations for this finding. In the usualcare group, even when clinicians did not know the procalcitonin assay result, they prescribed antibiotics less frequently to patients in the lower procalcitonin-level tiers than to those in the higher tiers. Patients with lower procalcitonin levels also had fewer clinical features of infection, and in that context, procalcitonin probably provided a modest amount of additional information to guide decisions. There was some suggestion of heterogeneity of the effect of the intervention, such as lower antibiotic prescription rates for patients with acute bronchitis than for those with other final diagnoses and a possible interaction between treatment effect and procalcitonin tier. However, these secondary analyses were exploratory, and the differences were largely nonsignificant.

Our findings contrast with those of previous trials of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic prescription in suspected lower respiratory tract infection. Possible reasons include differences in case mix, design, and setting. Previously, the largest effects on minimizing antibiotic exposure were observed among patients without pneumonia.11,42 We enrolled a high proportion of such patients, most of whom had low procalcitonin levels, which provided ample opportunity to detect an effect of the intervention on antibiotic exposure. Adherence to the procalcitonin guideline in previous trials was heavily mandated. We deployed the intervention using quality-improvement principles, including extensive use of education, prompts, and feedback. This design mimics a best-case scenario for deployment of a new intervention in the U.S. health care setting, but it probably yields lower clinician adherence than previous strategies. We accounted for this possibility by increasing the power of the trial to detect smaller effects; in addition, a per-guideline analysis that was restricted to patients for whom clinicians had followed the procalcitonin guideline at all time points and in which we controlled for selection bias yielded results similar to those in the primary intention-to-treat analysis. In the decade since the largest previous trial completed enrollment,11 there has been increased attention to antibiotic overuse and stewardship43 and movement toward shorter courses of antibiotic treatment based on evidence44 and guidelines.45 Such shifts in practice may have resulted in less opportunity for the intervention we examined to further reduce antibiotic exposure.

We considered whether the usual-care group may have received antibiotics at too low a rate, running the risk of unwanted recrudescence of infection. However, complications such as the development of organ dysfunction were infrequent, and the rates of adverse outcomes were lower than in other trials involving lower respiratory tract infection.46–48 Taken together, we presume that our findings can be attributed to the fact that the procalcitonin-based prescribing guideline provided fewer opportunities to change antibiotic decisions than in previous trials, both because clinicians in the usual-care group already commonly withheld antibiotics during emergency department and hospital encounters and because decisions to initially withhold antibiotics on the basis of procalcitonin level were subsequently overruled in the outpatient setting.

Strengths of our trial design included the fact that we ensured that serial procalcitonin results were delivered to clinicians in multiple emergency departments and hospitals, and we conducted the trial in a setting in which best practice based on current guidelines was promoted and in which background procalcitonin use was minimal. We also recruited patients for whom clinicians had uncertainty regarding the benefit of antibiotics, a feature that previous trials were criticized for lacking,49,50 and the trial was well powered to detect small differences in antibiotic exposure and to assess safety.

Our trial had some limitations. We did not directly address whether antibiotics can be safely withheld on the basis of a low procalcitonin level alone but rather tested the effect of a deployment strategy to promote the recommended use of the assay in clinical practice (in a patient population in which the likelihood of antimicrobial use was intermediate). In our strategy, procalcitonin assay results were provided to the clinical team before decision making in most but not all instances. A lack of knowledge about the prescribing practices used by individual physicians limits the insights we can make. The potential effect of emerging technology that may improve the rapid identification of infectious agents — technology that was largely unavailable during the course of this trial — is unclear. Finally, we did not achieve follow-up for all the patients in our trial, but our results were robust to complete-case and missing-not-at-random sensitivity analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (1R34GM102696–01 and 1R01GM101197–01A1). Procalcitonin assays and laboratory training were provided by bioMérieux. Dr. Peck-Palmer is a recipient of a University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Dean’s Faculty Advancement Award.

We thank the patients, families, clinical staff, and research staff who contributed to the trial; the full list of trial coordinators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

This article is dedicated to May K. Huang.

Appendix

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: David T. Huang, M.D., M.P.H., Donald M. Yealy, M.D., Michael R. Filbin, M.D., Aaron M. Brown, M.D., Chung-Chou H. Chang, Ph.D., Yohei Doi, M.D., Ph.D., Michael W. Donnino, M.D., Jonathan Fine, M.D., Michael J. Fine, M.D., Michelle A. Fischer, M.D., M.P.H., John M. Holst, D.O., Peter C. Hou, M.D., John A. Kellum, M.D., Feras Khan, M.D., Michael C. Kurz, M.D., Shahram Lotfipour, M.D., M.P.H., Frank LoVecchio, D.O., M.P.H., Octavia M. Peck-Palmer, Ph.D., Francis Pike, Ph.D., Heather Prunty, M.D., Robert L. Sherwin, M.D., Lauren Southerland, M.D., Thomas Terndrup, M.D., Lisa A. Weissfeld, Ph.D., Jonathan Yabes, Ph.D., and Derek C. Angus, M.D., M.P.H.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The complete list of the ProACT Investigators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org

The authors’ full names, academic degrees, and affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

References

- 1.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 2016; 315: 1864–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan C, Cars O. Antibiotic resistance — problems, progress, and prospects. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1761–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections — success that’s way off the mark: comment on “A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis.” JAMA Intern Med 2013;173: 273–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antibiotic use in the United States, 2017: progress and opportunities. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. (https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/hospital.html). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonkin-Crine SK, Tan PS, van Hecke O, et al. Clinician-targeted interventions to influence antibiotic prescribing behaviour for acute respiratory infections in primary care: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:CD012252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller B, White JC, Nylén ES, Snider RH, Becker KL, Habener JF. Ubiquitous expression of the calcitonin-I gene in multiple tissues in response to sepsis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet 1993;341:515–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang DT, Weissfeld LA, Kellum JA, et al. Risk prediction with procalcitonin and clinical rules in community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52(1): 48–58.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller B, Harbarth S, Stolz D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic accuracy of clinical and laboratory parameters in community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luyt CE, Guérin V, Combes A, et al. Procalcitonin kinetics as a prognostic marker of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 302: 1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bin-gisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet 2004;363:600–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest 2007; 131: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA clears test to help manage antibiotic treatment for lower respiratory tract infections and sepsis. News release of the Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, February 23, 2017. (https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm543160.htm). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Food and Drug Administration. Discussion and recommendations for the application of procalcitonin to the evaluation and management of suspected lower respiratory tract infections and sepsis. FDA Executive Summary; 2016. (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/medicaldevices/medicaldevicesadvisorycommittee/microbiologydevicespanel/ucm528156.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Wolbers M, et al. Procalcitonin guided antibiotic therapy and hospitalization in patients with lower respiratory tract infections: a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonagh M, Peterson K, Winthrop K, et al. Improving antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated acute respiratory tract infections Comparative effectiveness review no. 163. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016. (https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/antibiotics-respiratory-infection_research.pdf). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Assessment of communityacquired pneumonia. London: NICE, March 2018. (https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/pneumonia). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(5): e61–e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branche AR, Walsh EE, Vargas R, et al. Serum procalcitonin measurement and viral testing to guide antibiotic use for respiratory infections in hospitalized adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:1 692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolz D, Smyrnios N, Eggimann P,et al. Procalcitonin for reduced antibiotic exposure in ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomised study. Eur Respir J 2009; 34:1 364–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang DT, Angus DC, Chang CH, et al. Design and rationale of the Procalcitonin Antibiotic Consensus Trial (ProACT), a multicenter randomized trial of procalcitonin antibiotic guidance in lower respiratory tract infection. BMC Emerg Med 2017;1 7: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seymann GB. Community-acquired pneumonia: defining quality care. J Hosp Med 2006; 1:3 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bone RC. Toward an epidemiology and natural history of SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome). JAMA 1992;2 68: 3452–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 557–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-summary report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120: Suppl: S94–S138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180: 59–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loymans RJ, Ter Riet G, Sterk PJ. Definitions of asthma exacerbations. CurrOpin Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 11: 181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzales R, Sande MA. Uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Ann Intern Med 2000;1 33: 981–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barley EA, Quirk FH, Jones PW. Asthma health status measurement in clinical practice: validity of a new short and simple instrument. Respir Med 1998; 92: 120714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.03. 2010. (https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/codes_values.htm#ctc).

- 34.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 2010; 303: 2359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 2012; 308: 2594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bang H, Davis CE. On estimating treatment effects under non-compliance in randomized clinical trials: are intent-to-treat or instrumental variables analyses perfect solutions? Stat Med 2007; 26: 954–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim MY. Using the instrumental variables estimator to analyze noninferiority trials with noncompliance. J Biopharm Stat 2010; 20: 745–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ten Have TR, Normand SL, Marcus SM, Brown CH, Lavori P, Duan N. Intent-to-treat vs. non-intent-to-treat analyses under treatment non-adherence in mental health randomized trials. Psychiatr Ann 2008; 38: 772–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Kelly M, Ratitch B. Clinical trials with missing data: a guide for practitioners. Chichester, England:John Wiley, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;4 0: 373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Pro-calcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 10:C D007498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;6 2(10): e51–e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spellberg B The new antibiotic mantra — “shorter is better.” JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 1254–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: Suppl 2: S27–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobs DM, Noyes K, Zhao J, et al. Early hospital readmissions following an acute exacerbation of COPD in the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018. April 3 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, et al. Readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia: the impact of pneumonia type and its implication for hospitals. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasegawa K, Gibo K, Tsugawa Y, Shimada YJ, Camargo CA Jr. Age-related differences in the rate, timing, and diagnosis of 30-day readmissions in hospitalized adults with asthma exacerbation. Chest 2016; 149: 1021–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunha BA. Empiric antimicrobial therapy of community-acquired pneumonia: clinical diagnosis versus procalcitonin levels. Scand J Infect Dis 2009; 41: 782–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riedel S Procalcitonin and antibiotic therapy: can we improve antimicrobial stewardship in the intensive care setting? Crit Care Med 2012; 40: 2499–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.