Abstract

Risk assessment related to the exposure of humans to chemicals released into the environment is a major concern of our modern societies. In this context, toxicology plays a crucial role to characterize the effects of this exposure on health and identify the targets of these molecules. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) is an enabling technology for biodistribution studies of chemicals. Although the majority of published studies are presented in a pharmacological context, the concepts discussed in this review can be applied to the toxicological evaluation of chemicals released into the environment. The major asset of IMS is the simultaneous localization and identification of a parent molecule and its metabolites without labeling and without any prior knowledge. Quantification methods developed in IMS are presented with application to an environmental pollutant. IMS is effective in the localization of chemicals and endogenous species. This opens unique perspectives for the discovery of molecular alterations in metabolites and protein biomarkers that could help for a better understanding of toxicity mechanisms. Distribution studies of agrochemicals in plants by IMS can contribute to a better understanding of their mode of action and to a more effective use of these chemicals, avoiding the current concern of environmental damage.

Keywords: MALDI, Mass spectrometry, Imaging, Toxicology, Environmental pollutants

1. Introduction

A wide variety of exogenous molecules such as therapeutic drugs, agriculture and industrial chemicals, food additives and cosmetics are present in our environment (food, air, water and soil, animals and plants). The continuous exposure of humans to these chemicals released into the environment raises crucial questions about its impact on health. Different effects on respiratory, neurological immunological and endocrine systems are regularly reviewed (e.g., [1–6]). This recent awareness calls for the development of new analytical techniques that are able to provide rapid information on the tissular and molecular targets of these chemicals and their metabolites and also to study the biological processes implicated in their mechanisms of toxicity.

The risk assessment and the characterization of adverse effects of environmental pollutants on human health is therefore a major issue. Since 1981, the guidelines for the testing of chemicals are published and regularly updated by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). They gather internationally accepted methods used by government, university and industrial laboratories to determine the safety of chemicals by evaluating their physico-chemical properties, degradation and accumulation in the environment, effects on biotic systems (ecotoxicity) and on human health (toxicity). Toxicity tests must evaluate the different adverse effects (skin/eye irritation, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, developmental toxicity, one- and two-generation reproduction, etc.) observed after oral administration, inhalation or contact (via the skin) of each studied molecule at different dose levels (repeated, chronic or subchronic doses) [7]. As defined by the OECD test guidelines, toxicokinetic studies must be conducted to provide information on the absorption, distribution, metabolisation and excretion (ADME) of the tested molecule.

Toxicokinetic studies are generally based on the use of radiolabeled compounds and on the analysis of tissue homogenates or biological fluids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Quantitative whole-body autoradiography (QWBA) is a commonly used reference technique for distribution studies that involves the administration of the radiolabeled molecule, providing robust, sensitive and quantitative information. However, as QWBA only monitors radioactivity; the parent molecule cannot be differentiated from its metabolites or degradation products in situ. Therefore, metabolites are generally identified from the analysis of tissue homogenates or biological fluids, leading to the loss of information concerning their in situ localization. Since the last decade, IMS [8] has appeared as a powerful alternative for distribution and metabolism studies of small molecules (<1 kDa) [9–11] and could be also useful for the toxicological assessment of chemicals released into the environment.

In this review, we discuss the advantages of IMS for studying the distribution of small molecules and their subsequent metabolites. The future integration of IMS in toxicity tests requires the development of solid quantitative methods. The different approaches proposed for the quantification of small molecules by IMS as well as an example of its application to an environmental pollutant (chlordecone) are presented. The now well-known potential of IMS for the discovery of protein biomarkers that could help for a better understanding of toxicity mechanisms is also addressed. Although this review is mainly focused on toxicological aspects, the use of IMS for studying the distribution and metabolism of pesticides in plants is also presented. Indeed, this particular application of MALDI imaging is of great interest in the field of environmental research as it can help for a better use of pesticides or for the development of new molecules. Finally, the limits, perspectives and future applications of IMS to toxicological evaluation of chemicals released into the environment are discussed.

2. IMS simultaneously localizes the parent molecule and its metabolites

IMS offers some unique advantages over QWBA that is conventionally used for the analysis of compounds in tissues during toxicokinetic study of a molecule. IMS allows the localization of the molecule of interest without radioactive labeling, preserving the spatial information that is lost in conventional studies where tissue extracts or biological fluids are analyzed. The major advantage of IMS for distribution studies is its capacity to detect in situ the parent molecule and its metabolites without target specific reagents [12]. This represents an important time and cost saving compared to QWBA that necessitates the attachment of radiolabels at different positions of the molecule of interest to get a complete picture on metabolite formation and distribution. IMS is thus complementary to conventional techniques and could become a powerful tool to perform a faster and less expensive screening of the distribution of small molecules and their metabolites in tissues.

The majority of publications report the use of IMS for studying the distribution of therapeutic drugs and their metabolites in whole-body sections or in isolated organs (for review, see [9,11,13,14]). Although these studies are generally presented in a pharmacological context, the methods could be easily transposed to the toxicological evaluation of chemicals released into the environment. In 2006, IMS was successfully used for the first time by Kathib-Shahidi et al. [15] to simultaneously study the distribution of an antipsychotic drug (olanzapine) and two metabolites in whole-rat sections at various times after administration (Fig. 1). The distributions of olanzapine and its metabolites determined by IMS were perfectly coherent with previous data obtained by QWBA. In 2007, Stoeckli et al. directly compared QWBA and IMS with experiments carried out on a rat dosed with a radiolabeled compound [12]. The authors concluded that QWBA was more sensitive and more quantitative but concluded that IMS provided the simultaneous localization and unambiguous identification of the parent drug and its metabolites in the same section.

Fig. 1.

Simultaneous localization of olanzapine and its metabolites at 2 h post-dose in a whole-rat sagittal tissue section by IMS. A) Optical image of the dosed rat tissue section with organs outlined in red, and MALDI images of B) olanzapine (SRM transition m/z 313 ➔ 256), C) N-desmethyl metabolite (SRM transition m/z 299 ➔ 256) and D) of 2-hydroxymethyl metabolite (SRM transition m/z 329 ➔ 272). Adapted from Khatib-Sahidi et al. [15] with permission. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society.

Specificity is a crucial parameter for distribution studies and can be improved in different ways depending on the type of analyzer coupled to the MALDI ionization source. Single reaction monitoring (SRM) available on quadrupoles and ion traps can be used to monitor a fragment ion originating specifically from the precursor ion of interest and constituting a SRM transition [15,16]. This targeted analysis mode was successfully used by Khatib-Shaidi et al. for the distribution study of olanzapine and two metabolites presented in Fig. 1 [15]. Ion mobility can also be efficient in the separation of ions according to their gas phase mobility. Trim et al. were thus able to differentiate an anticancer drug (vinblastine) from isobaric lipids with this technology [17]. As a result of their high resolving powers, Fourier transform (FT) mass spectrometers (i.e., Orbitrap and FT-Ion Cyclotron Resonance) are extremely powerful in separating ions of small molecules from interfering matrix clusters or endogenous species and thus gain in specificity [18,19]. Moreover, the high mass accuracy of this type of instrument allows the measurement of exact masses. The concept of mass defect, defined as the difference between the nominal mass and the exact mass of a molecule, can thus be exploited and constitutes a significant aid for the identification of metabolites of a parent molecule [20]. As an example, the high mass accuracy of a MALDI-LTQ-Orbitrap system was advantageously exploited by Shahidi-Latham et al. to identify an unexpected metabolite of reserpine, an antihypertensive drug, in whole-rat sections using mass defect filters corresponding to common biotransformation analysis. The identity of this uncommon metabolite was then confirmed by MS/MS fragmentations [21]. The ultra-high mass accuracy and the precision of isotopic profiles typical of FT-ICR mass spectrometers open further possibilities as they can be used to determine the elemental composition of small molecules, thus greatly facilitating their identification. Cornett et al. demonstrated the benefits of FT-ICR mass spectrometers to obtain highly specific MALDI images of olanzapine in rat kidney and liver and of imatinib and its metabolites in mouse glioma [22]. Elemental compositions corresponding to metabolites were also highlighted. The identity of these metabolites was then confirmed by MS/MS fragmentations. In conclusion, combined with a confirmation by MS/MS fragmentations, the high performance levels of FT-ICR mass spectrometers are effective in providing highly specific MALDI images but also in the identification of in situ metabolites. The cost of ultra-high resolving power of FT-ICR mass spectrometers is the higher detection time compared to imaging systems based on time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzers. From our experience, with the same laser shot frequency, the acquisition times are about three times longer with a 7 T FT-ICR than with a TOF/TOF analyzer operating in reflectron mode.

3. Quantitative IMS: a prerequisite for its use in toxicologicalevaluation of chemicals

3.1. The different methods of quantitative IMS

The development of IMS for toxicological evaluation of small molecules absolutely requires solid quantification methods. However, such quantification is complicated with IMS for several reasons [23]. First, endogenous species present in a tissue section can affect the intensity of the ion of interest and can lead to varying ionization efficiency across the section. Second, the heterogeneity of matrix crystallization can induce signal variations. Finally, depending on the physico-chemical properties of the studied molecule and the composition of the matrix solution, the extraction of the compound of interest occurring during matrix application can be more or less efficient. Quantification by IMS is thus very challenging but is also essential for a future integration of IMS in toxicological evaluation. Consequently, the development of quantitative IMS methods has been the subject of very intensive researches over the past years [16]. The majority of published examples concern the quantification of drugs [24–29]. Thus, levels of tiotropium contained in lung of rats after inhalation of this bronchodilator were estimated by correlation with known amounts of tiotropium deposited on a control tissue section. The results were in good agreement with LCMS/MS quantification performed on tissue extracts [18,28]. Propranolol (a beta-blocker) and olanzapine were quantified by IMS in whole-body rat sections with a method based on the calculation of a tissue extinction coefficient (TEC) allowing the compensation of ion suppression effects for each organ [30]. Koeniger et al. also used olanzapine to demonstrate that the absolute quantity measured by LC-MS in serial liver sections could be correlated with the signal intensity detected by IMS [27]. A similar method was applied to the quantification of raclopride, a dopamine D2 receptor selective antagonist, in several mouse organs [31]. These different approaches without internal standard are well adapted to the quantification of chemicals in homogeneous tissues but results are more variable for highly structured tissues [30,32].

Variation in ionization efficiency effects across the tissue section and matrix crystallization heterogeneities can be corrected by approaches using an internal standard [32]. With normalization of the signal through use of an internal standard, relative standard deviations of approximately 10–15%, compatible with the OECD guidelines, for the testing of chemicals can be achieved [16,26,32,33]. These approaches differ mainly in the method used for the deposition of the internal standard that is generally the studied molecule labeled with stable isotopes (D, 13C, 15N, etc.). For the quantification of cocaine, Pirman et al. deposited the internal standard onto the ITO slide prior to the fixation of the tissue using a microspotter [29]. Kallback et al. quantified imipramine and tiotropium in the brain and lung of dosed rats by introducing the internal standard in the matrix solution deposited on the tissue section using a spraying device [26]. They also developed the msIQuant software available at http://www.maldi-ms.org for the signal normalization and the calculation of calibration curves.

A validated quantitative IMS approach was recently developed in which an isotopically labeled standard was deposited using a robotic spotter in an array of microspots (~200 μm in diameter) across a liver tissue section dosed with a drug [34]. Calibration standards were deposited on a non-dosed tissue section and analyzed in the same way as those on the dosed tissue. After the standards were deposited, matrix was applied to extract the internal standard and the analyte of interest from the dosed tissue section and the calibration standards using the same method. These methods were further validated with mouse kidney following in vivo treatment of the animal with promethazine (PMZ) [35]. Since drugs are filtered out of the blood in the cortex of the kidney, higher concentrations of PMZ were expected to be detected in the renal cortex than the renal medulla. Calibration standards (5–75 μM PMZ with 20 μM 2H3-PMZ) were deposited using a robotic spotter onto a non-dosed tissue section in both the medulla and the cortex. A quality control solution (25 μM PMZ with 20 μM 2H3-PMZ) was also deposited to ensure the method produced b15% error. The dosed tissue section was prepared by depositing 20 μM 2H3-PMZ in a 350 × 350 μm array across the section. Matrix solution (DHB) was deposited onto all calibration and internal standard microspots. The microspots were analyzed by IMS in the MS/MS mode to isolate and fragment the precursor ions for both PMZ and 2H3-PMZ in a large isolation window (m/z 286.6 ± 3.0). The quantitative image (Fig. 2) obtained shows the distribution of PMZ in which each microspot represents a concentration of PMZ. It can be seen that PMZ is localized to the cortex of the kidney. The quantitative IMS data for the entire tissue section was averaged and compared to HPLC-MS/MS data from extracts of the same kidney in which there was 98.8% agreement.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative IMS of kidney tissue dosed with PMZ along with an H&E stained serial section for histological comparison. The results from IMS and HPLC-MS/MS were in agreement for the entire tissue section, and the image provides additional information about the localization of PMZ to the cortex region of the kidney. Adapted from Chumbley et al. [34] with permission. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

3.2. Application of quantitative IMS to an environmental pollutant(chlordecone)

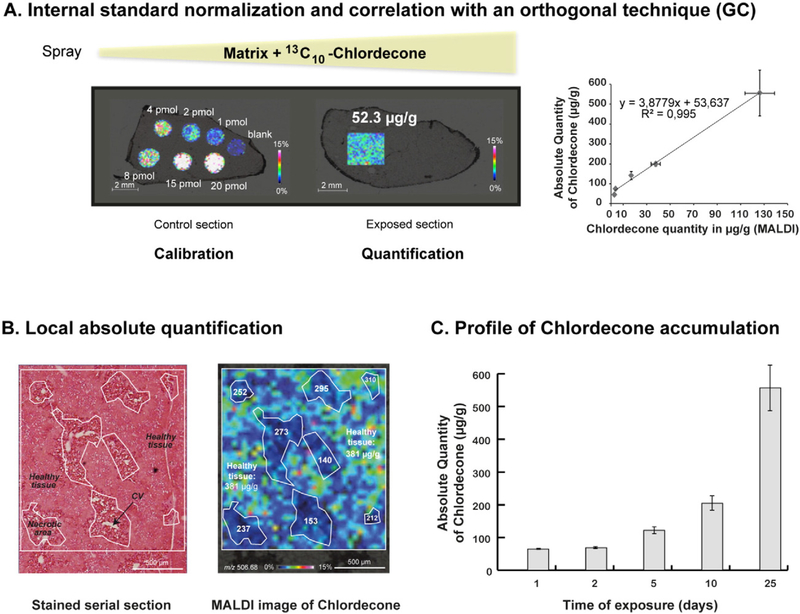

The methods for quantitative IMS that have been developed for therapeutic drugs can also be applied to environmental pollutants. Lagarrigue and coworkers [33] have recently demonstrated that IMS could be used for the in situ absolute quantification of chlordecone in the mouse liver. Chlordecone is an organochlorine pesticide that was extensively used in the French West Indies in banana plantations from 1973 to 1993. Its use has led to a persistent pollution of the environment and to the contamination of the local population for several decades with effects demonstrated on human health [36–38]. Our quantification method combines the normalization by an internal standard added to the matrix solution and the correlation with an orthogonal technique (e.g. GC) to achieve in situ absolute quantification (Fig. 3A). Indeed, in the particularly complex case of chlordecone, the quantities determined by IMS were not directly absolute quantities. This was probably due to different conversion rates of chlordecone into its hydrate form (the only form detectable by MALDI MS) and/or to different extraction yields of chlordecone between the exposed section and the calibration spots. After establishment of the correlation curve between the data from IMS and GC, absolute quantities were deduced from IMS data with the advantage of preserving in situ localization. This quantitative method allowed us to reveal a particular localization of chlordecone in the pathological liver of a chlordecone and CCl4 treated mouse (Fig. 3B). We were also able to determine the profile of chlordecone accumulation in the mouse liver at varying times of exposure (Fig. 3C). The sensitivity of this method was sufficient to detect chlordecone at a dose conventionally used for toxicological studies in rodents. Moreover, as shown in other publications, IMS offers the advantage of being able to extract quantitative information at the pixel level [16].

Fig. 3.

In situ absolute quantification of chlordecone in the mouse liver by IMS. A) The quantificationmethod was calibratedwith different amounts of chlordeconemanually spotted on acontrol section and normalized with an internal standard (13C10-chlordecone) added in the matrix solution. B) In situ absolute quantification of chlordecone in the pathological liver of achlordecone and CCl4 treated mouse with the microscopic image of a serial section stained with H&E and the MALDI image corresponding to chlordecone hydrate: the local absolutequantities measured in each necrotic areas are lower than that measured in the healthy tissue (381 μg/g). C) Accumulation profile of chlordecone in the mouse liver after an exposureof 1, 2, 5, 10, or 25 days at 5 mg/kg bw. Adapted from Lagarrigue et al. [33] with permission. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

4. Investigation of mechanisms of toxicity

The major goal of most toxicological studies is to understand the mechanisms of action of toxicants on biological systems. This is also evermore important in the case of environmental pollutants whose toxic mechanisms are generally not fully elucidated. Biological functions affected by exposure to a toxicant can be revealed by the identification of proteins and metabolites present in altered expression levels. For proteins, this is addressed using toxicoproteomics that has already been applied to a range of molecules such as drugs, natural products, industrial chemicals, metals and metalloids, nanoparticles and nanofibers (for review, see [39]). This approach is effective but relies generally on the analysis of tissue homogenates or biological fluids that leads to the loss of analyte localization. IMS can conserve this information without the need for complex sample preparation [40].

The potential of IMS for the discovery of potential biomarkers of pathologies has been demonstrated in several articles [41–46] and this approach can be applied for the discovery of toxicity biomarkers that could help for the elucidation of mechanisms of action. Meistermann et al. revealed an accumulation of a fragment of transthyretin (Ser28-Gln146) that could be used as a marker of nephrotoxicity in the cortex of rat kidney after administration of the antibiotic gentamicin [47]. As gentamicin binds to megalin, which is a ligand for transthyretin, the authors suggest that a preferential binding of megalin with gentamicin could prevent the efficient reabsorption of transthyretin into the bloodstream. Karlsson et al. observed a dose-dependent reduction of myelin basic protein in the striatum of adult rats brain neonatally exposed to the cyanobacterial toxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) [48]. This result, revealed by IMS and confirmed by immunohistochemistry, indicates that the neonatal exposure to BMAA could reduce or modify the myelination of axons in the striatum. This could explain cognitive impairments observed after exposure to BMAA in previous studies. Finally, Bauer et al. identified α-defensins (DEFAs) as protein markers of response to treatment of breast cancer patients with neoadjuvant paclitaxel and radiation using histology-guided MALDI profiling [49, 50]. After treatment with paclitaxel and radiation, DEFAs were found to be overexpressed in tumors of patients with pathologic complete response compared to patients with residual disease. This approach can be applied to the discovery of proteins as markers of the toxicity of environmental pollutants. A careful study of biological functions and molecular processes associated to these proteins could contribute to a better understanding of toxicity mechanisms.

5. Understanding the mode of action of agrochemicals in plants

Another dynamic field for the application of IMS directly related to environmental questions is the use of this technology to study the absorption, the distribution and the metabolism of agrochemicals in important to note that the presence of cuticles and plant cell walls at plants. This particular application is vital for a better understanding the plant surface can make IMS of plants very difficult [51,52]. They oband better control of the action of agrochemicals. However, it is tained molecular ion images of the fungicide azoxystrobin on the surface of soya leaves and in the stem of soya plants at different times after fungicide application. This study demonstrates the feasibility of IMS of pesticides in plants and revealed the absorption of azoxystrobin from the roots towards the stem of soya plants. Annangudi et al. used IMS to study the distribution of three fungicide residues (epoxiconazole, azoxystrobin, and pyraclostrobin) on the surface of wheat leaves [53]. In this study, the three fungicides were applied on leaf surface using a track sprayer system in order to simulate field application conditions. Their results characterized the behavior of agrochemicals on leaf surface after pesticide application. In 2009, Anderson et al. optimized the protocol of sample preparation to determine the distribution of nicosulfuron, a sulfonylurea herbicide extensively used in the cultivation of cereals, in sunflower sections taken from different regions of the stem after root or foliar uptake (Fig. 4) [54]. This study revealed different localizations of nicosulfuron and a phase 1 metabolite depending on the uptake type. This work also studied the distribution of four other sulfonylurea herbicides (chlorimuron-ethyl, chlorsulfuron, imazosulfuron and pyrazosulfuron-ethyl) in sunflower after foliar uptake [55]. Depending on the herbicide, the amplitude of the translocation from the application point towards the growing tips and/or towards the roots was shown to be very different.

Fig. 4.

MALDI imaging of azoxystrobin on wheat leaf after track sprayer application. Adapted from Annangudi et al. [53] with permission. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

6. Limitations and future perspectives

IMS has a great potential for application to studies involving the distribution and the metabolisation of chemicals released into the environment but also to better elucidate their mechanisms of action. Nevertheless, technological developments are still needed for further integration of IMS into in this research field. First, the sensitivity of IMS may not be sufficient to detect the studied molecule even in some cases where high doses of toxicant are used to induce observable effects. This can be due to the intrinsic ionization yield of the molecule of interest and/or to ion suppression effects and poor ion fragmentation for MS/ MS studies. Continuous accumulation of selected ions (CASI) available on some FT-ICR instruments can be used to improve sensitivity and dynamic range. This analysis mode, which consists in the selective accumulation of ions in a small mass range around the ion of interest before ion introduction in the ICR cell, was used by Groseclose et al. to significantly improve the detection sensitivity of lapatinib and nevirapine in rat liver [24]. Depending on the molecules, the limit of detection can be enhanced by a factor 10–50 with CASI [56].

The development of IMS for distribution studies performed on whole-body sections benefits from the reduction of acquisition times. New instruments have achieved laser shot frequencies of up to 10 kHz, enabling an enhancement of the lateral resolution of tissues because many more smaller pixels can be acquired in a short period of time. Images have been reported to be acquired with lateral resolutions of 20 μm [57] and 5 μm [58] and constitute important advances for the identification of cellular targets in the context of toxicological evaluation of chemicals released into the environment.

Although several methods have been developed for the identification of proteins detected by IMS, it remains tedious. Reported approaches are based on top-down [41,57,59] or bottom-up [43,60] analysis of tissue homogenates or directly from tissue sections using on-tissue enzymatic digestion [61] or in-source decay [62]. Nevertheless, unraveling the molecular complexity of tissue samples remains a daunting task. The use of high-resolution mass spectrometers [63] or coupling MS with ion mobility [64] holds great promise in helping overcome this issue.

7. Conclusion

The major application of IMS to address environmental questions is the analysis of the distribution studies of chemicals released into the environment and their metabolites in animals or in plants and the discovery of toxicity biomarkers to better elucidate mechanisms of action. The direct application of IMS to chemicals released into the environment is just emerging and will undoubtedly expand in the coming years. Indeed, since technological and methodological developments are still underway, different concepts such as distribution studies and biomarker discovery initially developed mainly for therapeutic drugs are now sufficiently advanced to be applied to chemicals released into the environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Inserm, the University of Rennes 1, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR, Contaminants et Environnements, CESA, ANR-11-CESA-0017), and in part by grants from Biogenouest, Infrastructures en Biologie Santé et Agronomie (IBiSA), Fonds Européen de Développement Régional and Conseil Régional de Bretagne. RC acknowledges funding from NIH (P41 GM103391).

Grant support

IBiSA, Regional council of Brittany, FEDER, ANR, NIH.

References

- [1].Dick S, Friend A, Dynes K, AlKandari F, Doust E, Cowie H, Ayres JG, Turner SW, A systematic review of associations between environmental exposures and development of asthma in children aged up to 9 years, BMJ Open. 4 (2014), e006554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kabir ER, Rahman MS, Rahman I, A review on endocrine disruptors and their possible impacts on human health, Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 40 (2015) 241–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kalkbrenner AE, Schmidt RJ, Penlesky AC, Environmental chemical exposures and autism spectrum disorders: a review of the epidemiological evidence, Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 44 (2014) 277–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kravchenko J, Corsini E, Williams MA, Decker W, Manjili MH, Otsuki T, Singh N, Al-Mulla F, Al-Temaimi R, Amedei A, Colacci AM, Vaccari M, Mondello C, Scovassi AI, Raju J, Hamid RA, Memeo L, Forte S, Roy R, Woodrick J, Salem HK, Ryan EP, Brown DG, Bisson WH, Lowe L, Lyerly HK, Chemical compounds from anthropogenic environment and immune evasion mechanisms: potential interactions, Carcinogenesis 36 (Suppl. 1) (2015) S111–S127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thompson PA, Khatami M, Baglole CJ, Sun J, Harris S, Moon EY, Al-Mulla F, AlTemaimi R, Brown D, Colacci A, Mondello C, Raju J, Ryan E, Woodrick J, Scovassi I, Singh N, Vaccari M, Roy R, Forte S, Memeo L, Salem HK, Amedei A, Hamid RA, Lowe L, Guarnieri T, Bisson WH, Environmental immune disruptors, inflammation and cancer risk, Carcinogenesis 36 (Suppl. 1) (2015) S232–S253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zeliger HI, Exposure to lipophilic chemicals as a cause of neurological impairments, neurodevelopmental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, Interdiscip. Toxicol 6 (2013) 103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parasuraman S,Toxicological screening, J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother 2 (2011) 74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Caprioli RM, Farmer TB, Gile J, Molecular imaging of biological samples: localization of peptides and proteins using MALDI-TOF MS, Anal. Chem 69 (1997) 4751–4760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Prideaux B, Stoeckli M, Mass spectrometry imaging for drug distribution studies, J. Proteome 75 (2012) 4999–5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Solon EG, Schweitzer A, Stoeckli M, Prideaux B, Autoradiography, MALDI-MS, and SIMS-MS imaging in pharmaceutical discovery and development, AAPS J. 12 (2010) 11–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cobice DF, Goodwin RJA, Andren PE, Nilsson A, Mackay CL, Andrew R, Future technology insight: mass spectrometry imaging as a tool in drug research and development, Br. J. Pharmacol 172 (2015) 3266–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stoeckli M, Staab D, Schweitzer A, Compound and metabolite distribution measured by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging in whole-body tissue sections, Int. J. Mass Spectrom 260 (2007) 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Reyzer ML, Chaurand P, Angel PM, Caprioli RM, Direct molecular analysis of whole-body animal tissue sections by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, Methods Mol. Biol 656 (2010) 285–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Angel PM, Caprioli RM, Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry: in situ molecular mapping, Biochemistry 52 (2013) 3818–3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Khatib-Shahidi S, Andersson M, Herman JL, Gillespie TA, Caprioli RM, Direct molecular analysis of whole-body animal tissue sections by imaging MALDI mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem 78 (2006) 6448–6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Porta T, Lesur A, Varesio E, Hopfgartner G, Quantification in MALDI-MS imaging: what can we learn from MALDI-selected reaction monitoring and what can we expect for imaging? Anal. Bioanal. Chem 407 (2015) 2177–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trim PJ, Henson CM, Avery JL, McEwen A, Snel MF, Claude E, Marshall PS, West A, Princivalle AP, Clench MR, Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-ion mobility separation-mass spectrometry imaging of vinblastine in whole body tissue sections, Anal. Chem 80 (2008) 8628–8634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goodwin RJ, Nilsson A, Borg D, Langridge-Smith PR, Harrison DJ, Mackay CL, Iverson SL, Andren PE, Conductive carbon tape used for support and mounting of both whole animal and fragile heat-treated tissue sections for MALDI MS imaging and quantitation, J. Proteome 75 (2012) 4912–4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Buck A, Halbritter S, Späth C, Feuchtinger A, Aichler M, Zitzelsberger H, Janssen K-P, Walch A, Distribution and quantification of irinotecan and its active metabolite SN-38 in colon cancer murine model systems using MALDI MSI, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 407 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sleno L, The use of mass defect in modern mass spectrometry, J. Mass Spectrom 47 (2012) 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shahidi-Latham SK, Dutta SM, Conaway MCP, Rudewicz PJ, Evaluation of an accurate mass approach for the simultaneous detection of drug and metabolite distributions via whole-body mass spectrometric imaging, Anal. Chem. 84 (2012) 7158–7165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cornett DS, Frappier SL, Caprioli RM, MALDI-FTICR imaging mass spectrometry of drugs and metabolites in tissue, Anal. Chem 80 (2008) 5648–5653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ellis SR, Bruinen AL, Heeren RM, A critical evaluation of the current state-of-theart in quantitative imaging mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem 406 (2013) 1275–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Groseclose MR, Castellino S, A mimetic tissue model for the quantification of drug distributions by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, Anal. Chem 85 (2013) 10099–10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hamm G, Bonnel D, Legouffe R, Pamelard F, Delbos JM, Bouzom F, Stauber J, Quantitative mass spectrometry imaging of propranolol and olanzapine using tissue extinction calculation as normalization factor, J. Proteome 75 (2012) 4952–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kallback P, Shariatgorji M, Nilsson A, Andren PE, Novel mass spectrometry imaging software assisting labeled normalization and quantitation of drugs and neuropeptides directly in tissue sections, J. Proteome 75 (2012) 4941–4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Koeniger SL, Talaty N, Luo Y, Ready D, Voorbach M, Seifert T, Cepa S, Fagerland JA, Bouska J, Buck W, Johnson RW, Spanton S, A quantitation method for mass spectrometry imaging, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 25 (2011) 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nilsson A, Fehniger TE, Gustavsson L, Andersson M, Kenne K, Marko-Varga G, Andren PE, Fine mapping the spatial distribution and concentration of unlabeled drugs within tissue micro-compartments using imaging mass spectrometry, PLoS ONE 5 (2010), e11411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pirman DA, Reich RF, Kiss A, Heeren RMA, Yost RA, Quantitative MALDI tandem mass spectrometric imaging of cocaine from brain tissue with a deuterated internal standard, Anal. Chem 85 (2013) 1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hamm G, Bonnel D, Legouffe R, Pamelard F, Delbos JM, Bouzom F, Stauber J, Quantitative mass spectrometry imaging of propranolol and olanzapine using tissue extinction calculation as normalization factor, J. Proteome 75 (2012) 4952–4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Takai N, Tanaka Y, Inazawa K, Saji H, Quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical drug distribution in multiple organs by imaging mass spectrometry, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 26 (2012) 1549–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pirman DA, Kiss A, Heeren RM, Yost RA, Identifying tissue-specific signal variation in MALDI mass spectrometric imaging by use of an internal standard, Anal. Chem 85 (2013) 1090–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lagarrigue M, Lavigne R, Tabet E, Genet V, Thome JP, Rondel K, Guevel B, Multigner L, Samson M, Pineau CG, Localization and in situ absolute quantification of chlordecone in the mouse liver by MALDI imaging, Anal. Chem 86 (2014) 5775–5783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chumbley CW, Reyzer ML, Allen JL, Marriner GA, Via LE, Barry III CE, RM C, Absolute quantitative MALDI imaging mass spectrometry: a case of rifampicin in liver tissues, Anal Chem. 88 (2016) 2392–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chumbley CW, Absolute Quantitative Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry and Imaging Mass Spectrometry of Pharmaceutical Drugs Directly from Biological Specimens, Vanderbilt University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Boucher O, Simard MN, Muckle G, Rouget F, Kadhel P, Bataille H, Chajes V, Dallaire R, Monfort C, Thome JP, Multigner L, Cordier S, Exposure to an organochlorine pesticide (chlordecone) and development of 18-month-old infants, Neurotoxicology 35 (2013) 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dallaire R, Muckle G, Rouget F, Kadhel P, Bataille H, Guldner L, Seurin S, Chajes V, Monfort C, Boucher O, Thome JP, Jacobson SW, Multigner L, Cordier S, Cognitive, visual, and motor development of 7-month-old Guadeloupean infants exposed to chlordecone, Environ. Res 118 (2012) 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Multigner L, Ndong JR, Giusti A, Romana M, Delacroix-Maillard H, Cordier S, Jegou B, Thome JP, Blanchet P, Chlordecone exposure and risk of prostate cancer, J. Clin. Oncol 28 (2010) 3457–3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rabilloud T, Lescuyer P, Proteomics in mechanistic toxicology: history, concepts, achievements, caveats, and potential, Proteomics 15 (2015) 1051–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Groseclose MR, Laffan SB, Frazier KS, Hughes-Earle A, Castellino S, Imaging MS in toxicology: an investigation of juvenile rat nephrotoxicity associated with dabrafenib administration, J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 26 (2015) 887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cazares LH, Troyer D, Mendrinos S, Lance RA, Nyalwidhe JO, Beydoun HA, Clements MA, Drake RR, Semmes OJ, Imaging mass spectrometry of a specific fragment of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase kinase 2 discriminates cancer from uninvolved prostate tissue, Clin. Cancer Res 15 (2009) 5541–5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lagarrigue M, Alexandrov T, Dieuset G, Perrin A, Lavigne R, Baulac S, Thiele H, Martin B, Pineau C, New analysis workflow for MALDI imaging mass spectrometry: application to the discovery and identification of potential markers of childhood absence epilepsy, J. Proteome Res 11 (2012) 5453–5463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lemaire R, Menguellet SA, Stauber J, Marchaudon V, Lucot JP, Collinet P, Farine MO, Vinatier D, Day R, Ducoroy P, Salzet M, Fournier I, Specific MALDI imaging and profiling for biomarker hunting and validation: fragment of the 11S proteasome activator complex, Reg alpha fragment, is a new potential ovary cancer biomarker, J. Proteome Res 6 (2007) 4127–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Minerva L, Ceulemans A, Baggerman G, Arckens L, MALDI MS imaging as a tool for biomarker discovery: methodological challenges in a clinical setting, Proteomics Clin. Appl 6 (2012) 581–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rauser S, Marquardt C, Balluff B, Deininger SO, Albers C, Belau E, Hartmer R, Suckau D, Specht K, Ebert MP, Schmitt M, Aubele M, Hofler H, Walch A, Classification of HER2 receptor status in breast cancer tissues by MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, J. Proteome Res 9 (2010) 1854–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Groseclose MR, Massion PP, Chaurand P, Caprioli RM, High-throughput proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue microarrays using MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, Proteomics 8 (2008) 3715–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Meistermann H, Norris JL, Aerni HR, Cornett DS, Friedlein A, Erskine AR, Augustin A, De Vera Mudry MC, Ruepp S, Suter L, Langen H, Caprioli RM, Ducret A, Biomarker discovery by imaging mass spectrometry: transthyretin is a biomarker for gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rat, Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5 (2006) 1876–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Karlsson O, Bergquist J, Andersson M, Quality measures of imaging mass spectrometry aids in revealing long-term striatal protein changes induced by neonatal exposure to the cyanobacterial toxin beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13 (2014) 93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bauer JA, Chakravarthy AB, Rosenbluth JM, Mi D, Seeley EH, De Matos G-IN, Olivares MG, Kelley MC, Mayer IA, Meszoely IM, Means-Powell JA, Johnson KN, Tsai CJ, Ayers GD, Sanders ME, Schneider RJ, Formenti SC, Caprioli RM, Pietenpol JA, Identification of markers of taxane sensitivity using proteomic and genomic analyses of breast tumors from patients receiving neoadjuvant paclitaxel and radiation, Clin. Cancer Res 16 (2010) 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cornett DS, Mobley JA, Dias EC, Andersson M, Arteaga CL, Sanders ME, Caprioli RM, A novel histology-directed strategy for MALDI-MS tissue profiling that improves throughput and cellular specificity in human breast cancer, Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5 (2006) 1975–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mullen AK, Clench MR, Crosland S, Sharples KR, Determination of agrochemical compounds in soya plants by imaging matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 19 (2005) 2507–2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Dong Y, Li B, Malitsky S, Rogachev I, Aharoni A, Kaftan F, Svatos A, Franceschi P, Sample preparation for mass spectrometry imaging of plant tissues: a review, Front Plant Sci. 7 (2016) 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Annangudi SP, Myung K, Avila Adame C, Gilbert JR, MALDI-MS imaging analysis of fungicide residue distributions on wheat leaf surfaces, Environ. Sci. Technol 49 (2015) 5579–5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Anderson DM, Carolan VA, Crosland S, Sharples KR, Clench MR, Examination of the distribution of nicosulfuron in sunflower plants by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry imaging, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 23 (2009) 1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Anderson DM, Carolan VA, Crosland S, Sharples KR, Clench MR, Examination of the translocation of sulfonylurea herbicides in sunflower plants by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation mass spectrometry imaging, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 24 (2010) 3309–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pu H, Hu N, Yen O, Direct detection of illegal additives in red wine using MALDIFTMS, 61st ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics Minneapolis, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lagarrigue M, Becker M, Lavigne R, Deininger SO, Walch A, Aubry F, Suckau D, Pineau C, Revisiting rat spermatogenesis with MALDI imaging at 20 μm resolution, Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10 (2011) (M110.005991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Van de Plas R, Yang J, Spraggins J, Caprioli RM, Image fusion of mass spectrometry and microscopy: a multimodality paradigm for molecular tissue mapping, Nat. Methods (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Maier SK, Hahne H, Moghaddas Gholami A, Balluff B, Meding S, Schoene C, AK W, Kuster B, Comprehensive identification of proteins from MALDI imaging, Mol. Cell. Proteomics (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Burnum KE, Tranguch S, Mi D, Daikoku T, Dey SK, Caprioli RM, Imaging mass spectrometry reveals unique protein profiles during embryo implantation, Endocrinology 149 (2008) 3274–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Groseclose MR, Andersson M, Hardesty WM, Caprioli RM, Identification of proteins directly from tissue: in situ tryptic digestions coupled with imaging mass spectrometry, J. Mass Spectrom 42 (2007) 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Debois D, Bertrand V, Quinton L, De Pauw-Gillet MC, De Pauw E, MALDI-in source decay applied to mass spectrometry imaging: a new tool for protein identification, Anal. Chem 82 (2010) 4036–4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Heeren RM, Smith DF, Stauber J, Kukrer-Kaletas B, MacAleese L, Imaging mass spectrometry: hype or hope? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 20 (2009) 1006–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bruand J, Sistla S, Meriaux C, Dorrestein PC, Gaasterland T, Ghassemian M, Wisztorski M, Fournier I, Salzet M, Macagno E, Bafna V, Automated querying and identification of novel peptides using MALDI mass spectrometric imaging, J. Proteome Res (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]