Abstract

Purpose:

Heavy metals and other elements may act as breast carcinogens due to estrogenic activity. We investigated associations between urine concentrations of a panel of elements and breast density.

Methods:

Mammographic density categories were abstracted from radiology reports of 725 women aged 40–65 years in the Avon Army of Women. A panel of 27 elements was quantified in urine using high resolution magnetic sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy. We applied LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) logistic regression to the 27 elements and calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dense versus non-dense breasts, adjusting for potential confounders.

Results:

Of the 27 elements, only magnesium (Mg) was selected into the optimal regression model. The odds ratio for dense breasts associated with doubling the Mg concentration was 1.24 (95% CI 1.03–1.49). Doubling the calcium-to-magnesium ratio was inversely associated with dense breasts (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.70–0.98).

Conclusions:

Our cross-sectional study found that higher levels of urinary magnesium were associated with greater breast density. Prospective studies are needed to confirm whether magnesium as evaluated in urine is prospectively associated with breast density and, more importantly, breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, environmental metals, breast density, magnesium, LASSO

INTRODUCTION

Women whose mammograms show extremely dense breasts have approximately three-fold risk of invasive breast cancer compared to women with less dense breasts (1–3). The biological mechanism whereby breast density is related to increased breast cancer remains unclear, but breast density shares several risk factors with breast cancer, including use of hormone therapy, nulliparity, and older age at first birth (1,2). Additionally, magnesium, calcium, and other elements have been proposed as factors that can protect (4–6) or promote cancer (7–11) but their associations with breast density are uncertain (11).

Magnesium is obtained from the diet with higher doses arising from green vegetables, nuts and unprocessed cereals, and lower concentrations are seen in dairy products and processed foods (4,12,13). Previous studies suggest that dietary intake in the United States is lower than the estimated average requirement (14). Magnesium is required for many physiologic functions (5,12,13), including cell proliferation, signaling transduction (4), and DNA repair and synthesis (15). In cases of hypomagnesemia, higher levels of free radicals and inflammation may lead to DNA damage and mutations that can result in cancer (4,6), which highlights the significance of optimal concentrations of magnesium in intracellular and extracellular compartments. Previous studies have hypothesized an association between magnesium and breast cancer (16),. However, few have investigated how magnesium and calcium – elements that are antagonistic in many physiologic functions (16, 17) – may be interconnected in their association with breast cancer.

The purpose of our study was to measure a panel of elements assessed in urine, including magnesium and calcium, and to describe associations of these elements with mammographic breast density, a marker of breast cancer risk.

METHODS

The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee approved this study. Women were recruited online from the Dr. Susan Love Foundation Army of Women volunteers between December 2012 and May 2013 (18). Eligibility was limited to women aged 40–74 years without a personal history of breast cancer or breast reduction surgery or breast implants. Women were also required to report receiving a mammogram within the past 18 months. Of 1,500 women that completed the online eligibility survey, 1,004 women were eligible and received study materials; 790 women completed the study questionnaire and returned a signed consent form, spot urine sample, and recent mammography report to the study center. Of the mammography reports, 27 had no mention of breast density and 38 had ambiguous descriptions of density. Hence, 725 women had complete study information and were included in statistical analysis.

The study questionnaire elicited information regarding lifestyle factors that may influence exposure to metals and other elements including multivitamin intake, alcohol consumption, smoking history, reproductive and menstrual history, hormone medication use, and demographic factors. Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) mammographic density categories were abstracted from radiology reports, defined as: a, almost entirely fatty; b, scattered fibroglandular density; c, heterogeneously dense; and d, extremely dense (19). Radiology reports were reviewed by a board-certified radiologist (E.S.B.), who adjudicated mammography reports that used density descriptors other than terminology recommended in the BI-RADS Atlas. BI-RADS classification has been widely used to describe breast density, has good reproducibility (20) and its association with breast cancer risk has been previously described (1).

Urine collection containers were sterile, acid-washed polypropylene bottles with screw top lids, a method previously used without evidence of contamination (10). A panel of 27 elements was quantified in urine using high resolution magnetic sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy including aluminum, antimony, arsenic, barium (Ba), beryllium, calcium (Ca), cadmium, cobalt, chromium, cesium (Cs), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), potassium (K), lithium (Li), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), molybdenum, sodium (Na), nickel (Ni), phosphorus, lead, strontium (Sr), thallium, uranium, vanadium, tungsten, and zinc (21). This panel was assembled based on known or suspected associations withcancer and includes known carcinogens, metalloestrogens, which have been previously associated with hormone-driven cancers (22), and several redox active metals (Fe, Mn, Cu, Ni) which are capable of producing excess reactive oxygen species and subsequent inflammatory cascades. The alkaline earths (Ba, Sr) and alkali metals (Na, K, Li, Cs) are included (in addition to Ca and Mg) as they reflect major ion homoeostasis in the body and several may compete for the same ion channels as the Ca and Mg. The panel also includes several elements present in multivitamin and multimineral supplements, whose associations with breast cancer remain unclear (23, 24).

Urinary element concentrations were normalized to urinary creatinine levels and log-transformed for statistical analysis. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) logistic regression was used to identify urinary metals associated with dense breasts (BI-RADS category c or d) as compared with non-dense breasts (BI-RADS category a or b) (25). In addition to the 27 elements, potential confounders included in the model included age, alcohol consumption, parity, race/ethnicity, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use, body mass index, and census region.

LASSO is a variable selection and regularization method for regression models that enhances both prediction accuracy and interpretability of the model. LASSO creates a path of optimal coefficients starting from the null model with no active covariates to a saturated model with all covariates included and unpenalized. The LASSO penalty (the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients) results in a sequence of optimal solutions with some covariates with coefficients set to zero (variable selection). The optimal LASSO solution was chosen to minimize the logistic regression deviance estimated using 10-fold cross-validation. The LASSO procedure is often described as a more democratic version of traditional forward stepwise regression, and the cross-validation procedure accounts for potential overfitting, indirectly accounting for multiple testing issues. The LASSO penalty was only applied to the 27 metals; the potential confounders were included without penalty in all models. Analyses were performed using the glmnet package in R version 3.2.3 (26).

RESULTS

Most of the women had dense breasts, BI-RADS c and d (65%). Women with non-dense breasts, BI-RADS a and b (35%), were more likely to be older, postmenopausal, and have greater body mass index compared to women with dense breasts BI-RADS c and d (Table 1).

Table 1:

Selected characteristics of participating women according to mammographically measured breast density, Avon Army of Women, 2014

| Non-dense breastsa N=252 % |

Dense breastsb N=473 % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||

| 40-45 | 10 | 14 |

| 46-50 | 15 | 21 |

| 51-55 | 19 | 23 |

| 56-60 | 20 | 20 |

| 61-65 | 36 | 22 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Never | 19 | 18 |

| Light | 44 | 47 |

| Moderate | 18 | 18 |

| Heavy | 19 | 18 |

| Multivitamin supplement use | ||

| No | 44 | 44 |

| Yes | 56 | 56 |

| Number of full-term pregnancies | ||

| 0 | 27 | 27 |

| 1 | 15 | 16 |

| 2 | 40 | 38 |

| ≥3 | 18 | 18 |

| Ancestry | ||

| European | 96 | 95 |

| Other | 4 | 5 |

| Postmenopausal hormone use c | ||

| Never | 58 | 64 |

| Former | 28 | 20 |

| Current | 13 | 15 |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Premenopausal | 23 | 37 |

| Postmenopausal | 77 | 61 |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never | 65 | 69 |

| Ever | 34 | 31 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| <25 | 37 | 63 |

| 25-30 | 33 | 29 |

| ≥30 | 29 | 8 |

| Geographic region of residence | ||

| Midwest | 30 | 21 |

| Northeast | 22 | 26 |

| South | 29 | 32 |

| West | 19 | 22 |

Defined as BI-RADS a (almost entirely fatty) and b (scattered fibroglandular density).

Defined as BI-RADS c (heterogeneously dense) and d (extremely dense).

Among postmenopausal women only.

Abbreviation: BI-RADS, Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System.

Mean values of the 27 elements according to breast density are shown in Table 2. In age-adjusted models, a doubling in the concentration of magnesium was associated with increased odds ratios of dense breasts (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.16–1.59). Confidence intervals for all of the remaining elements included the null value.

Table 2.

Univariate results of 27 heavy metals and elements in relation to mammographic density, Avon Army of Women, 2014

| Element | Non-dense breasts a Mean concentration (N=252) |

Dense breasts b Mean concentration (N=473) |

Age-Adjusted Odds Ratio c (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 5.19 | 4.51 | 0.95 (0.82-1.11) |

| Antimony | 0.0465 | 0.0456 | 1.01 (0.86-1.19) |

| Arsenic | 25.26 | 29.35 | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) |

| Barium | 2.12 | 2.48 | 1.04 (0.92-1.17) |

| Beryllium | 0.2123 | 0.1978 | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) |

| Calcium | 123,984.82 | 126,664.38 | 1.09 (0.95-1.25) |

| Cadmium | 0.2786 | 0.2487 | 0.97 (0.85-1.10) |

| Cobalt | 0.5076 | 0.5037 | 1.03 (0.91-1.18) |

| Chromium | 0.4972 | 0.4077 | 1.01 (0.89-1.15) |

| Cesium | 6.20 | 5.55 | 1.18 (0.91-1.52) |

| Copper | 6.34 | 5.96 | 0.85 (0.61-1.19) |

| Iron | 7.24 | 7.45 | 0.95 (0.82-1.11) |

| Potassium | 2,211,816.82 | 2,038,089.28 | 1.12 (0.96-1.30) |

| Lithium | 32.42 | 31.08 | 0.98 (0.83-1.17) |

| Magnesium | 51406.73 | 58,669.73 | 1.36 (1.16-1.59) |

| Manganese | 0.1602 | 0.1859 | 1.04 (0.92-1.19) |

| Molybdenum | 48.06 | 48.96 | 1.03 (0.87-1.19) |

| Sodium | 197,622.19 | 1,730,927.98 | 1.01 (0.90-1.14) |

| Nickel | 1.9138 | 1.8585 | 1.00 (0.87-1.15) |

| Phosphorus | 519,179.43 | 510,540.91 | 0.97 (0.79-1.19) |

| Lead | 0.4483 | 0.4036 | 1.07 (0.89-1.29) |

| Strontium | 146.43 | 236.25 | 1.12 (0.96-1.31) |

| Thallium | 0.1894 | 0.1820 | 1.21 (0.97-1.47) |

| Uranium | 0.01426 | 0.01561 | 1.06 (0.98-1.16) |

| Vanadium | 0.1299 | 0.1808 | 0.93 (0.81-1.07) |

| Tungsten | 0.5230 | 0.4058 | 0.98 (0.89-1.09) |

| Zinc | 258.71 | 232.61 | 0.94 (0.80-1.10) |

Defined as BI-RADS a (almost entirely fatty) and b (scattered fibroglandular density).

Defined as BI-RADS c (heterogeneously dense) and d (extremely dense).

Estimates the odds ratio for dense breasts associated with a doubling in the concentration of the elements, normalized for creatinine and adjusted for age.

Abbreviations: BI-RADS, Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System; CI, confidence interval.

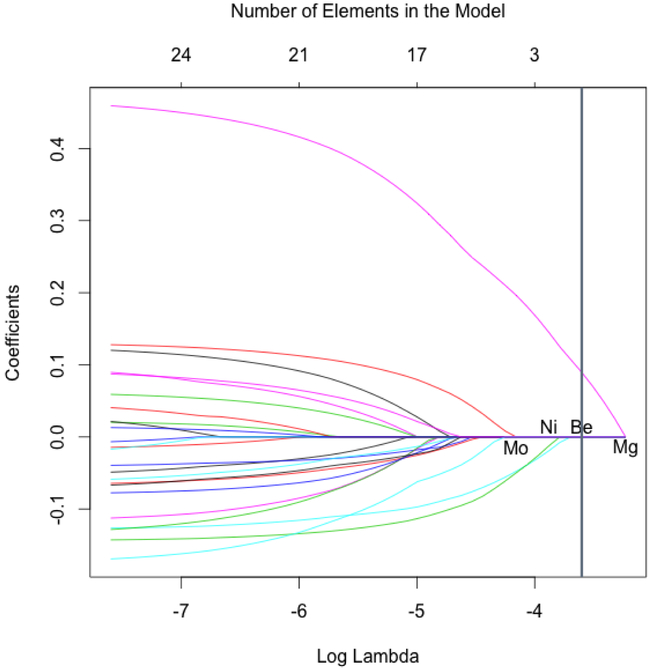

Of the 27 elements considered, only magnesium was selected as contributing to the optimal LASSO regression model (Figure). The last three elements to be dropped during automated variable selection—before the optimal model contained only magnesium—included beryllium, molybdenum, and nickel.

Figure.

Automated variable selection for a regression model of heavy metals and other elements in relation to breast density. Logistic regression coefficients for each element and the number of elements in the regression model shown as a function of the LASSO penalty parameter (log lambda). The model on the far left corresponds to the unconstrained maximum likelihood estimate (all elements); the model on the far right corresponds to the null model (no elements). The vertical line corresponds to the optimal model by cross-validation with a single element, magnesium. Every model includes all potential confounders. Abbreviations: LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; Be, beryllium; Mg, magnesium; Mo, molybdenum; Ni, nickel

A doubling in the concentration of magnesium was associated with a 1.24 odds ratio (95% CI 1.03 – 1.49) of dense breasts. After additional adjustment for the concentration of calcium, a doubling in the concentration of magnesium was associated with a 1.32 odds ratio (95% CI 1.06 – 1.65) of dense breasts. A doubling in the ratio of Ca:Mg was associated with a 0.83 odds ratio (95% CI 0.70–0.98) of dense breasts.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest a positive association between urine magnesium and dense breasts, and an inverse association with the Ca:Mg ratio, among healthy volunteers. To our knowledge this is the first report of these associations. Our confidence in the study results is supported by the large sample size, objective measure of the elements in urine, and statistical approach that permitted the single and joint contributions of each element.

Epidemiologic studies suggest that high levels of magnesium intake are associated with a lower incidence of esophageal and liver cancer (27–29), and decreased mortality due to colon, breast, prostate and ovarian cancers (7). Ma et al evaluated the dietary intake of magnesium among Japanese men and women, and concluded that higher dietary intake of magnesium decreased risk of colorectal cancer in men, but not in women (30). In our study, doubling of magnesium is associated with greater breast density, which could be a reflection of estradiol effects on breast tissue, magnesium reabsorption, and subsequent effects of the latter on normal cell proliferation (13). Higher mammographic density might be a result of increased epithelium and stroma proliferation (31).

Our results also suggest that a doubling in the Ca:Mg ratio was associated with lower mammographic breast density. Greater breast density is strongly associated with all breast cancer subtypes, but especially with larger tumor sizes, positive lymph nodes, and estrogen receptor-negative status.(32) These results are consistent with a published breast cancer study that showed that postmenopausal women with a higher Ca:Mg ratio had longer survival (16), possibly due to less aggressive features, lower recurrence and lower risk of a second primary (3). Using a prospective cohort of patients in Western New York State, Tao et al described improved overall survival among breast cancer patients that had higher magnesium dietary intake, and the association was stronger among those with high Ca:Mg ratio (16). However, Sahmoun et al hypothesized that a high Ca:Mg ratio is associated with increased cancer risk due to cell proliferation mediated by calcium (8), which was partially demonstrated by Sun et al using prostate cancer cells (9).

Magnesium homeostasis is mostly dependent on renal absorption, via active reabsorption mediated by transient receptor potential melastatin 6 (TRPM-6), and with minimal variations due to dietary intake (13). Reabsorption follows a circadian rhythm with maximal excretion at night (33) and further modulation is performed by estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, and epidermal growth factor (34,35). In vitro, 17β-estradiol has been associated with increased magnesium serum levels (34,36) which correlate with higher magnesium excretion among healthy menopausal women (37,38). In human studies, estrogen peaks at the time of ovulation are associated with low levels of ionized magnesium (38), elevated ionized calcium, and elevated Ca:Mg ratio; these effects might be caused by an intracellular shift of magnesium, due to unknown mechanisms (39).

Magnesium metabolism is altered in cancer cells (4,5,9) they contain higher intracellular concentration of magnesium than normal cells (7,5), and their growth is not inhibited by magnesium restriction (4,7), these adaptations provide metabolic advantages: resistance to senescence and apoptosis (40) inhibition of p53 tumor suppressor gene (41), and inhibition of DNA repair with altered response to normal growth signals (7).

A strength of our study is that by using healthy volunteers, we avoid confounding by magnesium metabolism changes and any other magnesium abnormalities observed in cancer patients (4,39). However, these heathly volunteers were, in general, highly educated and overwhelmingly of European ancenstry. A more diverse sample may provide greater variation in exposure levels to the 27 elements, including magnesium, which would facilitate evaluation of the relation between more extreme exposure values and breast density. In addition, our method of evaluation of magnesium levels was restricted to urine, and some individuals may have normal urine levels while intracellular magnesium is depleted (12,13). For these patients, a load test of magnesium or measurement of 24-hour urinary magnesium may more accurately reflect the intracellular status (21). While evidence suggests that urinary concentrations may be a fair measure of systemic load, more information is needed about the correlations between a one-time sample and 24 hour-collection, especially considering the circadian rhythm of magnesium excretion.

CONCLUSIONS

Our cross-sectional study suggests that higher levels of urine magnesium are associated with greater breast density; a doubling of the Ca:Mg ratio was inversely associated with density. Future studies are warranted to evaluate whether urine magnesium is prospectively associated with breast cancer risk.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Julie McGregor, Kathy Peck, Amy Godecker, Pam Skaar, Maria Tomasso, and the staff of the Dr. Susan Love Foundation Army of Women. This work was funded by the Avon Foundation for Women under grant 02–2011-116 and the United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute under grant P30CA014520 to the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center and grant P30 CA015704 to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Funding for Dr. Maria Mora-Pinzon salary was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health through the Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Vachon CM, Brandt KR, Ghosh K, Scott CG, Maloney SD, Carston MJ, et al. Mammographic breast density as a general marker of breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 16 (1):43–49, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vachon CM, van Gils CH, Sellers TA, Ghosh K, Pruthi S, et al. Mammographic density, breast cancer risk and risk prediction. Breast Cancer Res, 9 (6):217, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo CW, Chew GL, Britt KL, Ingman WV, Henderson MA, et al. Mammographic density-a review on the current understanding of its association with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 144 (3):479–502, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaszczyk U, Duda-Chodak A. Magnesium: its role in nutrition and carcinogenesis. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig, 64 (3):165–171, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra S, Parker DJ, Barth RF, Pannullo SC. Quantitative imaging of magnesium distribution at single-cell resolution in brain tumors and infiltrating tumor cells with secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS). J Neurooncol, 127 (1):33–41, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dibaba D, Xun P, Yokota K, White E, He K. Magnesium intake and incidence of pancreatic cancer: the VITamins and Lifestyle study. Br J Cancer, 113 (11):1615–1621, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castiglioni S, Maier JA. Magnesium and cancer: a dangerous liason. Magnes Res, 24 (3):S92–100, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahmoun AE, Singh BB. Does a higher ratio of serum calcium to magnesium increase the risk for postmenopausal breast cancer? Med Hypotheses, 75 (3):315–318, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Y, Selvaraj S, Varma A, Derry S, Sahmoun AE, et al. Increase in serum Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio promotes proliferation of prostate cancer cells by activating TRPM7 channels. J Biol Chem, 288 (1):255–263, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McElroy JA, Shafer MM, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Newcomb PA. Cadmium exposure and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst, 98 (12):869–873, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Gangnon RE, Buist DS, Burnside ES, et al. The vitamin D pathway and mammographic breast density among postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131 (1):255–265, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elin RJ. Assessment of magnesium status for diagnosis and therapy. Magnes Res, 23 (4):S194–198, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahnen-Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J, 5 (Suppl 1):i3–i14, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moshfegh A, Goldman J, Ahuja J, Rhodes D, Randy L What We Eat in America, NHANES 2005–2006: Usual Nutrient Intakes from Food and Water Compared to 1997 Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D, Calcium, Phosphorus, and Magnesium. Available at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/wweia-usual-intake-data-tables/ 2009. Accessed June 28, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Arora K, Beard WA, Wilson SH, Schlick T. Critical role of magnesium ions in DNA polymerase beta’s closing and active site assembly. J Am Chem Soc, 126 (27):8441–8453, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao MH, Dai Q, Millen AE, Nie J, Edge SB, et al. Associations of intakes of magnesium and calcium and survival among women with breast cancer: results from Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (WEB) Study. Am J Cancer Res, 6 (1):105–113, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardwick LL, Jones MR, Brautbar N, Lee DB. Magnesium absorption: mechanisms and the influence of vitamin D, calcium and phosphate. J Nutr, 121 (1):13–23, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Army of Women® - Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation. https://www.drsusanloveresearch.org/army-of-women. Accessed 10/06/2016, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, Appleton CM, Berg WA, et al. ACR BI-RADS® Mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA, American College of Radiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnikow J, Fenton JJ, Whitlock EP, Miglioretti DL, Weyrich MS, et al. Supplemental Screening for Breast Cancer in Women With Dense Breasts: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med, 164 (4):268–278, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen KE, Nabak AC, Johnson RE, Marvdashti S, Keuler NS, et al. Isotope concentrations from 24-h urine and 3-h serum samples can be used to measure intestinal magnesium absorption in postmenopausal women. J Nutr, 144 (4):533–537, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrne C, Divekar SD, Storchan GB, Parodi DA, Martin MB. Metals and Breast Cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia, 18(1):63–73, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misotti AM, Gnagnarella P. Vitamin supplement consumption and breast cancer risk: a review. Ecancermedicalscience,7:365, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wassertheil-Smoller S, McGinn AP, Budrys N, Chlebowski R, Ho GY, et al. Multivitamin and mineral use and breast cancer mortality in older women with invasive breast cancer in the women’s health initiative. Breast cancer Rese Treat, 141(3):495–505, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibshirani R Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. J Roy Stat Soc B Met, 58 (1):267–288, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw, 33 (1):1–22, 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CY, Chiu HF, Cheng MF, Tsai SS, Hung CF, et al. Esophageal cancer mortality and total hardness levels in Taiwan’s drinking water. Environ Res, 81 (4):302–308, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang CY, Chiu HF, Tsai SS, Wu TN, Chang CC. Magnesium and calcium in drinking water and the risk of death from esophageal cancer. Magnes Res, 15 (3–4):215–222, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko HJ, Youn CH, Kim HM, Cho YJ, Lee GH, et al. Dietary magnesium intake and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Nutrition and Cancer, 66(6), 915–923, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma E, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sawada N, et al. High dietary intake of magnesium may decrease risk of colorectal cancer in Japanese men. J Nutr, 140 (4):779–785, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huo CW, Chew G, Hill P, Huang D, Ingman W, et al. High mammographic density is associated with an increase in stromal collagen and immune cells within the mammary epithelium. Breast Cancer Res, 4;17:79, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertrand KA, Tamimi RM, Scott CG, Jensen MR, Pankratz V, et al. Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer by age and tumor characteristics. Breast Cancer Res, 15 (6):R104, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanabrocki EL, Scheving LE, Olwin JH, Marks GE, McCormick JB, et al. Circadian variation in the urinary excretion of electrolytes and trace elements in men. Am J Anat 166 (2):121–148, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groenestege WM, Hoenderop JG, van den Heuvel L, Knoers N, Bindels RJ. The epithelial Mg2+ channel transient receptor potential melastatin 6 is regulated by dietary Mg2+ content and estrogens. J Am Soc Nephrol, 17 (4):1035–1043, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tejpar S, Piessevaux H, Claes K, Piront P, Hoenderop JG, et al. Magnesium wasting associated with epidermal-growth-factor receptor-targeting antibodies in colorectal cancer: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol, 8 (5):387–394, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao G, van der Wijst J, van der Kemp A, van Zeeland F, Bindels RJ, et al. Regulation of the epithelial Mg2+ channel TRPM6 by estrogen and the associated repressor protein of estrogen receptor activity (REA). J Biol Chem, 284 (22):14788–14795, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNair P, Christiansen C, Transbol I. Effect of menopause and estrogen substitutional therapy on magnesium metabolism. Miner Electrolyte Metab, 10 (2):84–87, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muneyyirci-Delale O, Nacharaju VL, Dalloul M, Altura BM, Altura BT. Serum ionized magnesium and calcium in women after menopause: inverse relation of estrogen with ionized magnesium. Fertil Steril, 71 (5):869–872, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Facchinetti F, Borella P, Valentini M, Fioroni L, Genazzani AR. Premenstrual increase of intracellular magnesium levels in women with ovulatory, asymptomatic menstrual cycles. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2 (3):249–256, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell, 100 (1):57–70, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Guezennec X, Bulavin DV. WIP1 phosphatase at the crossroads of cancer and aging. Trends Biochem Sci, 35 (2):109–114, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]