Abstract

Despite prior extensive investigations of the interactions between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, few studies have simultaneously considered activation and structural connectivity in this circuit, particularly as it pertains to adolescent socioemotional development. The current multi-modal study delineated the correspondence between uncinate fasciculus (UF) connectivity and amygdala habituation in a large adolescent sample that was drawn from a population-based sample. We then examined the influence of demographic variables (age, gender, and pubertal status) on the relation between UF connectivity and amygdala habituation. 106 participants (15–17 years) completed DTI and an fMRI emotional face processing task. Left UF fractional anisotropy was associated with left amygdala habituation to fearful faces, suggesting that increased structural connectivity of the UF may facilitate amygdala regulation. Pubertal status moderated this structure-function relation, such that the association was stronger in those who were less mature. Therefore, UF connectivity may be particularly important for emotion regulation during early puberty. This study is the first to link structural and functional limbic circuitry in a large adolescent sample with substantial representation of ethnic minority participants, providing a more comprehensive understanding of socioemotional development in an understudied population.

Keywords: amygdala, emotion, adolescence, fMRI, DTI

Introduction

Perceiving, interpreting, and responding appropriately to facial expressions are essential skills for successful socioemotional function across development. Two key regions involved in emotion processing are the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex (Banks, Eddy, Angstadt, Nathan, & Phan, 2007; Davidson 2002; Fusar-Poli et al., 2009; Haxby et al., 2002; Monk et al., 2003; Nelson, Leibenluft, McClure, & Pine, 2005). Heightened activation in the amygdala in response to emotional faces is associated with affect-related disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) in both adolescents and adults (McClure et al., 2007; Monk, Klein, et al., 2008; Monk, Telzer, et al., 2008; Peluso et al., 2009; Phan, Fitzgerald, Nathan, & Tancer, 2006.; Swartz, Phan, Angstadt, Fitzgerald, & Monk, 2014). The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is well-connected structurally to the amygdala (Barbas, 2000), with the ventral PFC (vPFC) in particular helping to modulate its function (Hariri et al., 2003; Nomura et al., 2004). However, what is less clear is how the amygdala-vPFC circuit functions in adolescence, limiting our ability to understand the etiology of adolescent affect-related disorders.

During adolescence, a developmental period when peer social interactions are highly salient, the neural networks involved in emotion processing undergo significant structural change (Blakemore, 2008; Lenroot & Giedd, 2006). Whereas the amygdala goes through substantial development during childhood (Giedd et al., 1996; Mosconi et al., 2009; Schumann et al., 2004; Tottenham & Sheridan, 2009), the prefrontal cortex experiences a protracted development and continues to mature through adolescence (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008; Gogtay et al., 2004; Sowell et al., 1999; Sowell et al., 2003). During this time, cortical gray matter volume in the frontal lobe decreases from its peak volume in late childhood (11 years for girls and 12.1 years for boys), reflecting pruning of these regions and myelination of gray matter (Lenroot & Giedd, 2006; Giedd 2008). White matter increases linearly throughout adolescence (Lenroot & Giedd, 2006), improving neuronal communication. Pruning and increased neuronal connectivity help to strengthen information transfer between prefrontal cortical and subcortical regions (Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008).

The major white matter tract connecting the ventral prefrontal cortex and the amygdala is the uncinate fasciculus (UF), which is the primary conduit of bidirectional communication within amygdala-vPFC circuit (Von Der Heide, Skipper, Klobusicky, & Olson, 2013). The vPFC is hypothesized to modulate amygdala reactivity (Hariri et al., 2003; Monk et al., 2008; Nomura et al., 2004), suggesting that increased structural connectivity of the UF facilitates vPFC regulation of amygdala reactivity. However, little work has examined if UF structural connectivity relates to amygdala reactivity. Further, if the UF is facilitating amygdala downregulation, its structural connectivity should relate to amygdala habituation, defined as a decrement in amygdala reactivity during a task due to repeated stimulus presentation (Plichta et al., 2014; Rankin et al., 2009). Amygdala habituation is hypothesized to result from prefrontal cortical downregulation of amygdala reactivity and facilitate acclimation to our surroundings. Additionally, amygdala habituation is a more reliable indicator of amygdala function (Gee et al., 2015; Plichta et al., 2014). Importantly, no prior work has evaluated the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala habituation.

Further, UF structural connectivity increases throughout childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood (Hasan et al., 2009; Swartz et al., 2014). As a result, adolescence poses a unique challenge to this system. Namely, the UF is in flux, while at the same time the socioemotional environment is rapidly changing. The underlying neurobiology is not yet stabilized, possibly remaining flexible in the face of a changing environmental and hormonal landscape. Despite the potential importance of this developmental phenomenon, surprisingly, little is known about how connectivity between crucial regions develops.

Beyond structural changes, the neural networks involved in emotion processing also experience significant functional development during adolescence. Amygdala responsivity to socioemotional stimuli decreases from adolescence to adulthood (Guyer, Monk et al., 2008; Hare et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2015; Scherf, Smyth, & Delgado, 2013; Somerville, Fani, & McClure-Tone, 2011; Somerville, Jones, & Casey, 2010), but this finding is not consistent (McRae et al., 2012; Pfeifer & Allen 2012; Vasa et al., 2011). Prefrontal cortical regions involved in socioemotional function (e.g., face processing) consistently demonstrate reduced reactivity from adolescence into adulthood (Blakemore 2008; Blakemore 2012; Burnett et al., 2009; Burnett, Sebastian et al., 2011; Gunther Moor et al., 2011; Pfeifer & Blakemore, 2012; Pfeifer, Lieberman, & Dapretto, 2007; Monk et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2015). Additionally, functional connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex in response to social contexts increases in adolescence (Pfeifer, Masten et al., 2011; Spielberg, Jarcho et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2015). As with structural development, reactivity of neural regions essential to emotion processing change significantly during adolescence, a period of substantial alterations in the socioemotional environment. Although studying structural and functional development separately has yielded important insights, this approach is limited in that it cannot address bidirectional influences between structural and functional development (Cicchetti & Dawson, 2002). For example, changes in brain structure may facilitate or inhibit changes in brain function or vice versa. It is particularly important to study neural structure and function simultaneously in adolescence, as this is a developmental stage marked by significant changes in both neural structure and function and is also a time of potential flexibility in response to changing environments, hormones, and neural development. In order to attain a more comprehensive understanding of the neural bases of socioemotional development during adolescence, it is essential to utilize and integrate multiple modalities.

To date, only a small number of studies have explored the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. Increased structural connectivity of the UF is thought to facilitate prefrontal cortical regulation of the amygdala (Swartz et al., 2014; Tromp et al., 2012). Consistent with this premise, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has shown that fractional anisotropy (FA) values, which reflect the extent to which diffusion is constrained in a single direction and index the connectivity of a fiber tract (Jones, Knösche, & Turner, 2013; Thomason & Thompson, 2011), in the UF are inversely related to amplitude of amygdala response to sad and happy faces in youth (9.6 – 19.2 years of age) recruited from a college town (Swartz et al., 2014). Increased structural connectivity in childhood and adolescence may facilitate decreases in amygdala reactivity that are often observed across development (Swartz et al., 2014), suggesting that increased structural connectivity would be associated with decreased amygdala reactivity in youth. However, in a study of older adolescents and young adults (16.95 – 25.25 years of age) recruited from a college town, UF FA positively correlated with amygdala reactivity to fearful faces (compared to neutral faces; Kim & Whalen, 2009). The inconsistency in findings between these two studies highlights the need for further work to clarify the relation between UF FA and amygdala regulation, particularly during development. Indeed, both Kim & Whalen (2009) and Swartz et al. (2014) relied on relatively small (N < 40) convenience samples recruited from college towns (Kim & Whalen, 2009; Swartz et al., 2014), limiting their applicability to the general population.

Previous work evaluating the relation between UF structural connectivity, amygdala reactivity, and development focused on age, so the role of puberty is less clear. Specifically, the one developmental study to examine UF FA and amygdala activation found that the relation is moderated by age in a child and adolescent sample (9– 19 years old), such that younger participants demonstrate a stronger relation between UF FA and amygdala activation (Swartz et al., 2014). However, the influence of puberty was not examined. Pubertal hormonal changes have been shown to relate to distinct aspects of neural maturation (Spear, 2000; Sisk & Foster, 2004; Blakemore, Burnett, & Dahl, 2010; Galván, Van Leijenhorst, & McGlennen, 2012), so pubertal stage is an important consideration when conducting neuroimaging studies of adolescence. Previous work exploring the relation between pubertal stage and socioemotional processing has been mixed; advancing pubertal stage has been both positively (Moore et al., 2012) and negatively (Forbes et al., 2012) associated with amygdala activation to emotional faces (Galván, Van Leijenhorst, & McGlennen, 2012). The divergence of these findings highlights the importance of further work exploring the role of pubertal stage in socioemotional processing. In addition, there are sex differences in adolescent structural (Schmithorst & Yuan, 2010) and functional (Tahmasebi et al., 2012) neural development. Therefore, sex should be an important consideration when studying puberty and adolescent neural development. However, whether sex influences the relation between neural structure and function is unclear. Despite these intriguing findings, prior studies have not examined the effects of puberty and sex on the relation between UF connectivity and amygdala reactivity.

The primary objective of the current study was to further characterize how UF structural connectivity is related to amygdala function in adolescents. We improved upon previous work in three ways: 1) we examined amygdala habituation, a more reliable indicator of amygdala function (Gee et al., 2015; Plichta et al., 2014); 2) we used DTI acquisition methods that improved image quality; and 3) we recruited a large sample of adolescents drawn from a population-based sample that provides greater representation of adolescents of color and families from lower SES contexts, populations often understudied in neuroimaging research (Falk et al., 2013). Since our participants were closer in age to the participants in Swartz et al. 2014 than those in Kim & Whalen 2009, we hypothesized that greater UF structural connectivity would predict greater amygdala habituation to emotional faces. In light of findings indicating that age moderates the relation between UF FA and activation (Swartz et al., 2014), our second objective was to assess the potential moderation of the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala habituation by age, pubertal status, and gender. We hypothesized that age and pubertal status would moderate the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala habituation. Finally, given that demographic variables (puberty, age, and sex) have been linked to alterations in socioemotional and neural development, but their influences on the relations between structure and function are unclear, our third objective was to examine the relations between demographic variables, UF structural connectivity, and amygdala habituation. We hypothesized that age and pubertal status would be positively associated with UF FA and amygdala habituation.

Methods

Participants

The University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board approved this study. All adolescent participants provided written informed assent, and their primary caregivers provided written consent for both themselves and their adolescent children, after the study was explained and questions were answered. 106 adolescents from the Detroit or Toledo subsamples of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) (Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001) successfully completed both fMRI and DTI scanning. The FFCWS is a population-based sample of children born in large US cities, with an oversample of non-marital births (Table 1). At the beginning of the national FFCWS study, 42.16% of mothers indicated that their household income in the last 12 months was $25,000 or less; 60.51% indicated that their household income in the last 12 months was $50,000 or less. FFCWS families were interviewed at the birth of the focal child, and when the child was 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15 years of age. The population of the city of Detroit at the time of the FFCWS baseline was predominantly African-American (Brookings Institute, 2003), and the Detroit sample was significantly larger than the Toledo sample (Reichman et al., 2001), so our sample has substantial (73.6%) representation of African American families. One hundred eighty-seven adolescents participated in the current study at the time of analysis, but 16 were unable to be scanned (e.g., due to braces) and 6 were declined to participate in scanning. An additional 44 participants were removed from analyses for several other reasons including: not completing the fMRI task (N = 5); fMRI scan quality issues (e.g., significant portions of the brain not covered, N = 8); low coverage of the left or right amygdala (N = 13); low accuracy (<70%) on the task faces (N = 15); outliers on habituation (extracted amygdala habituation was less than (Q1 (lower quartile)-3*IQR (interquartile range)) or greater than (Q3 (upper quartile) +3*IQR); (N = 2)); and ASD diagnosis (N = 1). For DTI analyses, an additional 15 participants were removed due to incomplete DTI data acquisition (N = 4) and/or DTI image artifacts (N = 11; Table 2). Additionally, comparison was not possible in a small number of participants for which DTI measures from the UF could not be extracted due to inability of tractography to trace the UF, because the FA fell below 0.15 or the minimum angle between current and previous path segments exceeded 30 degrees (Thomason et al., 2010) (N = 8 for the left and 2 for the right). The participants who had useable fMRI and DTI data did not differ on age, t(163.04) = −0.12266, p = 0.9025, pubertal status, t(151.68) = −0.97555, p = 0.3308, or gender, χ2 (22) = 25.134, p = 0.2907, from participants who did not. Of the adolescents who were included in the present analyses, 73.6% were Black / African American, 14.2% were White/ Caucasian, and 47.2% of families reported annual income below $25,000.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Measure | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 61(57.5%) |

| Male | 45(42.5%) |

| Race | |

| Black / African-American | 78(73.6%) |

| White / Caucasian | 15(14.2%) |

| Asian | 1(0.9%) |

| Other | 1(0.9%) |

| Multiracial | 6(5.7%) |

| Missing | 5(4.7%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 6(5.7%) |

| Not Hispanic | 98(92.5%) |

| Missing | 2(1.9%) |

| Measure | Mean(SD), Range |

| Age (months) | 188.12(5.04), 180–202 |

| Puberty | 2.94(0.44), 1.8 – 4.0 |

Table 2.

Sample attrition.

| Number of Subjects | |

|---|---|

| Original Sample | 187 |

| fMRI analyses attrition | |

| Did not attempt MRI scan | 22 |

| Incomplete fMRI scan | 5 |

| fMRI scan quality issues (e.g., image distortion) | 8 |

| (<70%) amygdala coverage (left or right) | 13 |

| (<70%) accuracy on faces task | 15 |

| Habituation outlier | 2 |

| ASD | 1 |

| Total included in habituation analyses | 121 |

| DTI analyses attrition | |

| Incomplete DTI scan | 4 |

| DTI scan quality (>7 artifacts) | 11 |

| Unable to extract L UF measures | 8 |

| Unable to extract R UF measures | 2 |

| Total included in habituation & L UF analyses | 98 |

| Total included in habituation & R UF analyses | 104 |

Procedures

Gender identification task

Participants completed an implicit emotion face processing task during continuous fMRI acquisition. In this task, participants were asked to identify the gender of the actor by pressing their thumb for male or their index finger for female on a button box. Faces from the NimStim set (Tottenham et al., 2009) were used and were counter balanced for gender and race (European American and African American). There were 100 pseudo-randomized trials, 20 trials each of the following emotions: fearful, happy, sad, neutral, and angry. Each trial consisted of a fixation cross (500 ms), followed by a face (250 ms), then a black screen (1500 ms) during which participants responded to the face, and finally a second black screen (jittered inter-trial interval: 2, 4, or 6 s). This task is particularly well-suited for studying emotion processing, as the quick presentation time of the face stimuli does not provide opportunity for participants to saccade away from the stimuli (Mattson et al., under review). Accuracy and response times were recorded.

fMRI data acquisition

fMRI data was collected with a GE Discovery MR750 3T MRI scanner with an 8-channel head coil. We collected functional T2*-weighted BOLD images with a gradient echo spiral sequence (TR = 2000ms, TE = 30ms, contiguous 3 mm axial slices, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 22cm, voxel size = 3.44mm x 3.44 mm x 3mm) aligned with the AC-PC plane.

DTI data acquisition

We collected DTI data after fMRI scanning using a spin echo diffusion sequence (TR = 7250ms, TE = minimum, FOV = 22cm, thickness = 3mm, 40 slices, with b = 1000 s/mm2, and 64 non-linear directions). To transform the diffusion-weighted images to a MNI template, one non-diffusion weighted image (b = 0 s/mm2) was also collected.

Puberty

Pubertal development was measured using adolescent self-report on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988), which has had high correlations (0.61 – 0.67) with physician ratings (Brooks-Gunn, Warren, Rosso, & Gargiulo, 1987). Total scores range from 1 to 4.

Gender

Adolescent self-report of gender was determined using the Pubertal Development Scale; specifically, if they answered female- or male-specific questions on the scale.

Age

Date of birth was collected using adolescent self-report and parent confirmation on an fMRI safety screener, and then the date of the visit and date of birth were used to calculate age in months.

Psychopathology

Current psychopathology was determined with the K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997). A trained clinical interviewer (e.g., psychology doctoral student, post-baccalaureate staff) administered the semi-structured interview to the target child and primary caregiver individually. Assessors were trained by two licensed clinical psychologists with 25+ years combined experience with the K-SADS. Training included practice interviews and live supervision of interviews with families. The interviewer arrived at initial DSM-V diagnoses and symptom counts, which were then reviewed in case conferences with two licensed clinical psychologists (authors LWH and NLD).

Analyses

fMRI data analysis

Anatomical images were homogeneity-corrected using SPM, then skull-stripped using the Brain Extraction Tool in FSL (version 5.0.7) (Smith, 2002; Jenkinson, Pechaud, & Smith, 2005). The functional imaging data then had the following preprocessing steps applied: removal of large temporal spikes in k-space data (> 2 std dev), field map correction and image reconstruction using custom code in MATLAB; and slice-timing correction using SPM8.6313 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). The rest of preprocessing was also done in SPM8, including: grey matter segmenting anatomical images; realigning segmented anatomical and functional images to the AC-PC plane; coregistering anatomical and functional images; spatially normalizing functional images into MNI space; and smoothing functional images with a Gaussian filter set to 8 mm FWHM. We conducted image analyses using the general linear model of SPM8. After preprocessing, Artifact Detection Tools (ART) software (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/artifact_detect) identified motion outliers (>2mm movement or 3.5° rotation). Outliers were censored from individual participant models using a single regressor for each outlier volume. Given susceptibility of the amygdala to signal loss, only those participants with a minimum of 70% coverage in the left and right amygdala at a threshold of p < 1, as defined by Automated Anatomical Labeling atlas regions of interest (ROIs; Maldjian, Laurienti, Burdette, & Kraft, 2003; Maldjian, Laurienti, & Burdette, 2004; Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002), were included in group-level analyses. To ensure that participants were engaged in the task, only those with accuracy of 75% or greater were included in group analyses. Condition effects were modeled at the individual level, with incorrect trials modeled as a separate condition and excluded from subsequent analyses. To assess habituation, we divided the task in half and a separate regressor for each emotion (fearful, happy, sad, neutral, and angry) and half of the task (1st half, 2nd half) was created, yielding 10 regressors of interest (e.g., early and late fearful).

DTI data analysis

We conducted preprocessing and analysis of diffusion weighted images using MrDiffusion, part of the mrVista package (https://white.stanford.edu/software/). Preprocessing involved head motion correction using eddy current correction and linear registration to the nondiffusion weighted image (b=0 image). Based on concerns about DTI artifacts (Soares, Marques, Alves, & Sousa, 2013), three independent raters checked each volume for white pixel or other forms of artifact. If any individual rater considered an artifact to be present in a volume, that volume was marked as having an artifact. We removed participants with artifacts in 8 or more directional volumes from analyses. To ensure equal statistical support of DTI metrics, participants included in the analyses each had a total of 7 volumes removed. These 7 volumes included any volumes with artifacts and then volumes selected by a random number generator. Using regions of interest included in the Johns Hopkins University White Matter Tractography Atlas (Mori et al., 2005), we extracted multiple white matter tracts using the same methodology described in detail in our prior works (Swartz et al., 2014; Thomason et al., 2010).

Group analyses

Amygdala habituation to faces

We tested amygdala habituation in SPM8 by subtracting activation to the second half of the task from activation to the first half of the task (Swartz et al., 2013; Wiggins, Swartz, Martin, Lord, & Monk, 2013). This and all subsequent analyses were small volume corrected (SVC) using anatomically defined (Automated Anatomical Labeling atlas) left and right amygdala masks created with the Wake Forest University PickAtlas (Maldjian et al., 2003; Maldjian et al., 2004; Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) to maintain a voxelwise family-wise error of p < 0.05. The effects of each emotion (fearful, happy, sad, neutral, and angry) were tested separately, as we wanted to explore the specificity of any effect. We corrected for multiple comparisons in subsequent regression analyses by setting Bonferroni correction to p < 0.004 in addition to the voxelwise family-wise error of p <.05. This correction was determined by dividing 0.05 by twelve; we tested 6 emotions (all, fear, happy, sad, neutral, and angry) in both the left and right sides of the amygdala. Using structural regions of interest from the Wake Forest University PickAtlas, we extracted individual parameter estimates for the change in amygdala reactivity during the task to use in confirmatory analyses.

Objective 1: Relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation

To assess the relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation, multiple regression analysis in SPM8 was conducted in which UF FA was regressed onto amygdala habituation. In separate analyses, we regressed extracted mean FA values from the left and right UF onto the contrasts of each emotion (all faces, fearful, happy, sad, neutral, angry) versus baseline. Significance was evaluated for the regression of left FA values for the left amygdala ROI and right FA values for the right amygdala ROI. Again, we corrected for multiple comparisons (left and right side as well as six emotions) by setting Bonferroni correction to p < 0.004.

We also conducted control analyses in RStudio to determine whether the relation between amygdala habituation and FA values was specific to the UF. This allowed us to determine whether global differences in white matter maturation contributed to DTI effects, or if effects were isolated to UF circuitry. To do this, we selected the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), two of the control tracts used by Swartz et al. (2014). We examined correlations between amygdala habituation (extracted from the structural amygdala ROI from WFU Pickatlas) and mean FA from the UF, SLF and ILF in RStudio 1.0.136 (RStudio Team).

Objective 2: Moderation of relations between amygdala habituation and UF by age, pubertal status, and gender

We assessed age, pubertal status, and gender as potential moderators of any significant relations between amygdala habituation and UF FA. To examine moderation, we tested whether the interaction between the predictor variable (UF FA) and the moderator variable (age, pubertal status, or gender) significantly predicted the outcome variable (amygdala habituation) in RStudio. If the interaction was significant, then the effect of UF FA on amygdala habituation differed depending on the moderator. We visualized significant moderation using the rockchalk package (Johnson, 2017) in RStudio.

Objective 3: Relations between demographic variables, UF, and amygdala habituation

We evaluated whether amygdala habituation varied by age, pubertal status, and gender. To assess the influences of age and pubertal status on amygdala habituation, we conducted multiple regression analyses in SPM8. We evaluated the role of gender in amygdala habituation by conducting an ANOVA in SPM8. For each demographic variable assessed, we corrected for multiple comparisons (left and right side and six emotions) by setting Bonferroni correction to p < 0.004.

We also evaluated whether UF FA varied by age, pubertal status, and gender. We ran Pearson’s correlations in RStudio to test whether mean UF FA varied with age or pubertal status, and then conducted a t-test in RStudio to determine whether mean UF FA differed by gender.

Task performance

To ensure that amygdala habituation was not a result of changes in accuracy or reaction time, we compared accuracy and reaction time in the first and second halves of the task using paired t-tests in RStudio. If there was a significant difference, we then evaluated whether the change in accuracy or reaction time between the two halves of the task was related to extracted amygdala habituation.

Motion outliers

We evaluated whether the number of motion outliers detected by ART throughout the scan related to our demographic variables of interest (age, gender, pubertal status), and compared the number of motion outliers in the first and second halves of the scan in RStudio in order to ensure that any results were not driven changes in motion. If there was a significant relation between motion outliers and demographic variables or difference in motion outliers between the two halves of the scan, we then evaluated whether this was related to amygdala habituation.

Current psychopathology

To ensure that our findings were not solely due to current psychopathology, we removed all participants with a current DSM-V disorder diagnosis and re-ran main analyses with the smaller sample (albeit with reduced power).

Results

Amygdala habituation to faces

We observed significant habituation in the right, but not left, amygdala at the group level mean (see Table 3). Specifically, the right amygdala demonstrated significant habituation to the contrasts all faces versus baseline and neutral faces versus baseline. Though the left amygdala did not show significant habituation at the group level (i.e., the group mean of T2-T1 was not significantly different from 0), there was substantial individual variability (left amygdala habituation to fear mean = 0.0002; SD = 0.614; range = −2.023 – 1.331) in habituation scores and thus these scores were examined in relation to UF FA.

Table 3.

Amygdala habituation to faces.

| Contrast | Side | t(120) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All1>All2 | L | 2.74 | 0.051 | −30 | −6 | −14 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Sad1>Sad2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | L | 2.82 | 0.044 | −18 | −2 | −14 |

| Angry1>Angry2 | L | 2.67 | 0.053 | −28 | −8 | −12 |

| All1>All2 | R | 4.71 | < 0.001 | 32 | −8 | −12 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | R | 2.17 | 0.162 | 32 | −8 | −12 |

| Happy1>Happy2 | R | 2.42 | 0.099 | 28 | −8 | −14 |

| Sad1>Sad2 | R | 3.17 | 0.018 | 32 | −8 | −12 |

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | R | 4.17 | 0.001 | 32 | −2 | −12 |

| Angry1>Angry2 | R | 3.43 | 0.008 | 32 | −8 | −12 |

Note: FWE-corrected is based on structurally-defined amygdala regions of interest. FWE = family-wise error; coordinates are in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. Bolded type indicates that finding survives Bonferroni correction for 12 comparisons.

UF FA

The mean extracted left UF FA value was 0.304 (SD = 0.024, range = 0.261–0.390) and the mean extracted right UF FA value was 0.300 (SD = 0.021, range = 0.233–0.359).

Objective 1: Relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation

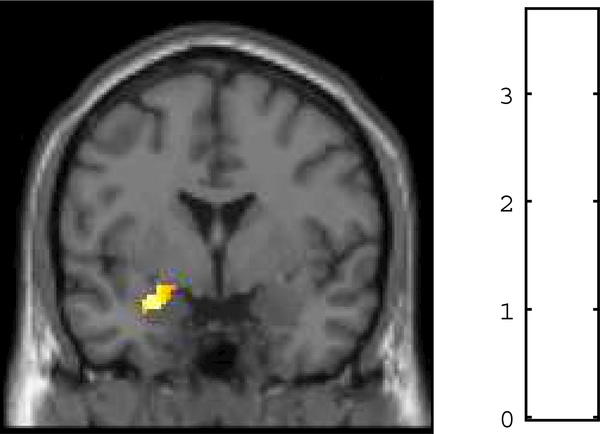

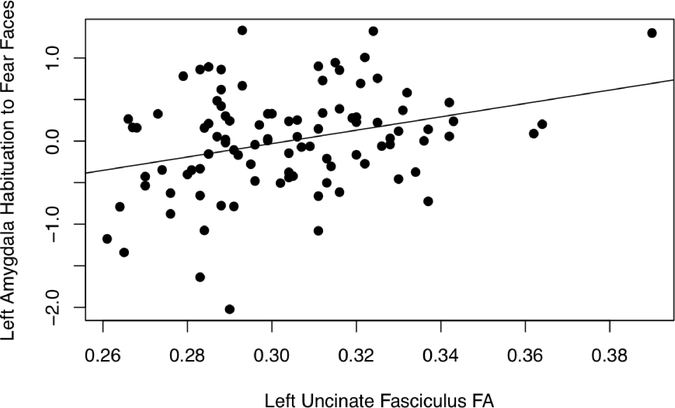

Multiple regression analyses in SPM8 examining the relation between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation revealed a positive relation, such that higher FA values were associated with more amygdala habituation to fearful faces, t (96) = 3.76, p = .003, XYZ = −26, −2, −18; see Table 4 and Figure 1. This was also found in confirmatory correlation analyses in RStudio, r (96) = 0.314, p = 0.002; see Figure 2. In addition, we evaluated the influence of one extreme score on left UF FA by removing it and re-running the correlation analyses, which yielded similar results.

Table 4.

Relation between uncinate fasciculus FA and amygdala habituation to faces.

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of UF FA, t(96) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All1>All2 | L | 2.48 | 0.091 | -24 | 0 | -16 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | L | 3.76 | 0.003 | -26 | -2 | -18 |

| Happy1>Happy2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Sad1>Sad2 | L | 2.97 | 0.03 | -20 | 0 | -12 |

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | L | 2.37 | 0.107 | -24 | 4 | -18 |

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of UF FA, t(102) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

| All1>All2 | R | 2.57 | 0.086 | 28 | -8 | -14 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | R | 2.28 | 0.143 | 26 | -6 | -16 |

| Happy1>Happy2 | R | 1.93 | 0.255 | 24 | 0 | -18 |

| Sad1>Sad2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | R | 1.87 | 0.271 | 28 | -8 | -14 |

Note: FWE-correction is based on structurally-defined amygdala regions of interest. FWE = familywise error; coordinates are in MNI space. Bolded type indicates that finding survives Bonferroni correction for 12 comparisons.

Figure 1.

There was a positive relation between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces, t (96) = 3.76, p = .003, XYZ = −26, −2, −18. Left UF FA estimates were extracted from a structural left UF ROI and entered as regressors in a multiple regression analysis in SPM8. Note: we would like figure 1 to be in color.

Figure 2.

In a confirmatory analysis in RStudio, Left amygdala habituation to fearful faces is positively correlated with mean FA values extracted from the left UF, r = 0.314, p = 0.002. Left amygdala habituation parameter estimates were extracted from a structural left amygdala ROI from WFU PickAtlas, and left UF FA estimates were extracted from a structural left UF ROI.

There were no significant relations between right UF FA and right amygdala habituation. Control analyses assessing the relations between SLF and ILF FA and amygdala habituation found no significant relations for either side.

Objective 2: Moderation of relation between amygdala habituation and UF FA by age, pubertal status, and gender

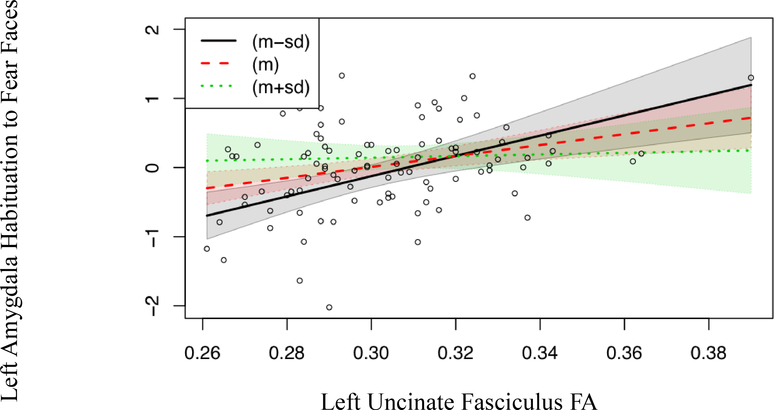

We tested whether age or pubertal status moderated the association between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. The regression including the moderation effect of puberty was significant, R2 = 0.18, F(3,92) = 6.786, p = 0.0003, and the interaction of puberty and left UF FA, B = −15.340, SE = 6.464, t (95) = −2.373, p = 0.0197, significantly predicted left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. To ensure that this moderation effect was specific to puberty, we tested whether the interaction of puberty and left UF FA was still significant after including age as a term in the regression. The regression that included age as well as the moderation effect of puberty was still significant, R2 = 0.18, F(4,91) = 5.063, p = 0.001, indicating that the interaction of puberty and left UF FA, B = −15.256, SE = 6.502, t (95) = −2.347, p = 0.02112, predicted left amygdala habituation to fearful faces even after accounting for age. The relation between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces is stronger for participants who are earlier in pubertal development, see Figure 3. Follow-up F tests to compare variances in left UF FA and left amygdala habituation between those above and below the average for puberty revealed variance in left amygdala habituation to fearful faces was trending towards being greater for participants who were earlier in pubertal development, F(37,57) = 1.7061, p = 0.06809. Neither the interaction of age and left UF FA, B = 0.7902, SE = 0.5134, p = 0.127, nor the interaction of gender and left UF FA, B = 8.275, SE = 4.973, p = 0.0994, predicted left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. Finally, we evaluated the influence of one extreme score on left UF FA by removing it and re-running the analyses, which gave similar results.

Figure 3.

The association between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces is moderated by puberty, B = −15.340, SE = 6.464, t (95) = −2.373, p = 0.0197, such that left UF FA was more predictive of left amygdala habituation to fearful faces in participants who were earlier in pubertal development relative to participants who were later in pubertal development. The coloring in the figure represents pubertal status; the dotted green line and green shading represents participants who are later in pubertal development (at the mean plus the standard deviation of pubertal development for this sample or greater), the dashed red line and red shading represents participants who are average in their pubertal development, and the black solid line and black shading represent participants who are earlier in pubertal development (at the mean minus the standard deviation of pubertal development for this sample or less). Note: we would like figure 3 to be in color.

Objective 3: Relations between demographic variables, UF FA, and amygdala habituation

We assessed whether age, pubertal status, or gender related to either amygdala habituation or UF FA. We did not find significant relations between age and amygdala habituation (see Table 5). Further, we did not find significant relations between pubertal status and amygdala habituation (see Table 6). Amygdala habituation and UF FA did not differ by gender. Neither age nor puberty were significantly related to UF FA.

Table 5.

Relation between age and amygdala habituation to faces.

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of age, t(104) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All1>All2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Fear1>Fear2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Sad1>Sad2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | L | 2.70 | 0.054 | −20 | −6 | −16 |

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of age, t(104) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

| All1>All2 | R | 2.84 | 0.047 | 22 | 2 | −16 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | R | 2.79 | 0.048 | 22 | 2 | −16 |

| Sad1>Sad2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | R | 2.52 | 0.097 | 24 | 0 | −12 |

| Angry1>Angry2 | R | 3.53 | 0.007 | 22 | −4 | −16 |

Note: FWE-correction is based on structurally-defined amygdala regions of interest. FWE = family-wise error; coordinates are in MNI space. Bolded type indicates that finding survives Bonferroni correction for 12 comparisons.

Table 6.

Relation between pubertal status and amygdala habituation to faces.

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of pubertal status, t(102) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All1>All2 | L | 1.73 | 0.323 | −18 | −4 | −12 |

| Fear1>Fear2 | L | 3.33 | 0.012 | −22 | −6 | −16 |

| Happy1>Happy2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Sad1>Sad2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Contrast | Side | Positive effect of pubertal status, t(102) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

| All1>All2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Fear1>Fear2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Sad1>Sad2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Contrast | Side | Negative effect of pubertal status, t(102) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

| All1>All2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Fear1>Fear2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | L | 2.35 | 0.115 | −30 | −4 | −14 |

| Sad1>Sad2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | L | > 0.100 | ||||

| Contrast | Side | Negative effect of pubertal status, t(102) | p-value(FWE) | X | Y | Z |

| All1>All2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Fear1>Fear2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Happy1>Happy2 | R | 2.31 | 0.136 | 32 | −8 | −12 |

| Sad1>Sad2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Neutral1>Neutral2 | R | > 0.100 | ||||

| Angry1>Angry2 | R | > 0.100 |

Note: FEW-correction is based on structurally-defined amygdala regions of interest. FWE = family-wise error; coordinates are in MNI space. Bolded type indicates that finding survives Bonferroni correction for 12 comparisons.

Task performance

After removing participants with below 70% accuracy, the average accuracy across the task was 94.68% (SD = 5.97%, range = 72.00–100.00%) and the average reaction time (RT) was 709.74 ms (SD = 126.99 ms, range = 501.76 – 998.21 ms). Accuracy did not significantly differ between the first and second halves of the task t(105) = 1.7037, p = 0.091, but reaction time did, t(105) = 2.528, p = 0.013. Average RT was slower in the first half of the task (mean = 718.43 ms, SD = 137.26 ms, range = 475.10 – 1072.88 ms) than in the second half of the task (mean = 701.05 ms, SD = 126.17 ms, range = 495.43 – 1007.50 ms. The change in accuracy between the first and second halves of the task was not significantly related to amygdala habituation to any emotion on either hemisphere of the brain (all p > 0.17). The change in reaction time between the first and second halves of the task was also not significantly related to amygdala habituation to any emotion on either hemisphere of the brain (all p > 0.094).

Motion outliers

The total number of motion outliers detected by ART throughout the fMRI scan did not relate to age, gender, or pubertal status (all p > 0.50). However, the number of motion outliers detected by ART did differ between the first and second halves of the scan, t(105) = −2.0561, p = 0.04. The change in number of motion outliers from the first half to the second half of the scan was related to left amygdala habituation to angry faces, t(96) = −3.1336, p = 0.002, right amygdala habituation to fearful faces, t(104) = 3.0958, p = 0.0025, and right amygdala habituation to happy faces, t(104) = 2.3772, p = 0.0193. However, these contrasts are not involved in the significant findings of this paper.

Current psychopathology

When excluding participants with current DSM-V disorder diagnoses (n = 30), left UF FA was still associated with left amygdala habituation to fearful faces, but the finding became a trend, likely due to reduced statistical power associated with a reduced sample size, r(67) = 0.23, p = 0.055. Even with reduced power, the regression including the moderation effect of puberty was still significant, R2 = 0.15, F(3,63) = 3.593, p = 0.01834, and the interaction of puberty and left UF FA, B = −22.617, SE = 9.860, t (66) = −2.294, p = 0.0251, significantly predicted left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. We still found no significant relations between gender, age, puberty, and left UF FA or left amygdala habituation to fearful faces in the sample that excluded participants with current psychopathology diagnoses.

Discussion

The present study characterized the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala function in a large sample drawn from a population-based sample and with substantial representation of understudied youth – African-American adolescents and adolescents from lower SES families. We found a significant positive relation between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. Further, we found that pubertal status moderated the relation between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation, such that this relation was stronger for participants who were earlier in pubertal development.

As hypothesized, greater UF structural connectivity predicted larger amygdala habituation to emotional faces. That is, increased UF FA was associated with a greater reduction in amygdala response to fearful faces over the course of the task. Although prior work has not examined the relation between UF connectivity and amygdala habituation, our results were more consistent with Swartz and colleagues’ finding that UF FA structural connectivity predicted reduced amygdala activation, than Kim and Whalen’s finding that UF FA structural connectivity predicted increased amygdala activation (Kim & Whalen, 2009; Swartz et al., 2014). Further, the relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation that we found supports the hypothesis that the UF facilitates amygdala downregulation. Importantly, this relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation was specific to the left hemisphere of the brain. The laterality of this finding was consistent with previous work examining the relation between UF FA and amygdala activity in youth; Swartz et al. (2014) found significant relations in the left hemisphere only. Results of a meta-analysis suggested that the right amygdala is involved in a more short-term response to emotional stimuli, whereas the left amygdala engages in more sustained responses (Sergerie, Chochol, & Armony, 2008). Bidirectional communication between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex may be more influential on the sustained responses of the left amygdala, whereas the temporal dynamics of the right amygdala may result in effective habituation with less prefrontal cortical input. This research may also explain our finding of group-level habituation in the right amygdala only; it is possible that the temporal dynamics of the right amygdala are such that there is less individual difference in habituation, whereas individual differences in bidirectional communication between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex are more significant for left amygdala habituation, even when the group mean is 0. The role of amygdalaprefrontal cortex circuitry may differ by hemisphere, but further work is warranted to clarify potential differences by hemisphere.

The positive relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation suggested that increased structural connectivity of the UF facilitates prefrontal cortical regulation of the amygdala in adolescence. However, theoretical accounts of adolescent development posit that a dual-systems model where limbic reactivity is increased and prefrontal cortical activity is immature in adolescence may be overly simplistic (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Pfeifer & Allen, 2012). Therefore, further empirical work is needed in order to better understand the nuances of affective neural development in adolescence; Pfeifer and Allen (2012) suggested that research combining neuroimaging modalities may be particularly helpful. Our study is the first to combine fMRI and DTI to explore the relations between amygdala habituation and UF structural connectivity. Our finding that increased structural connectivity was related to increased amygdala downregulation helped to clarify the previous literature by utilizing habituation instead of activation, which is thought to index emotion regulation. Future work should integrate structural and functional connectivity of limbic circuitry in adolescence in order to determine whether the UF facilitation of amygdala habituation is due to PFC downregulation, which would be reflected as increased UF structural connectivity and increased amygdala-PFC functional connectivity both relating to amygdala habituation. Further, Gee and colleagues (2013) found that previously institutionalized youths exhibited more mature bilateral amygdala-medial PFC connectivity, and that this was associated with reduced anxiety (Gee et al., 2013). Increased habituation has also been linked to reduced anxiety; individuals with higher trait anxiety demonstrated reduced amygdala habituation in the left amygdala (Hare et al., 2008). It may be that altered amygdala-PFC connectivity and amygdala habituation in the left hemisphere may contribute to anxiety, but further work is warranted. A prior quantitative meta-analysis (Wager, Phan, Liberzon, & Taylor, 2003) found no support for a hypothesis of overall lateralization of emotional function. In a systematic review, Baas, Aleman, & Kahn (2004) found that the left amygdala is more often activated than the right amygdala, and this predominant left amygdala activation is not due to stimulus type, task instructions, different habituation rates between left and right amygdala, and elaborate processing. A recent review suggests that functional lateralization of emotion in the amygdala is modulated by sex, with the greatest impairments being associated with righthemisphere lesions in men and left-hemisphere lesions in women (Reber & Tranel, 2017). Nevertheless, Hare and colleagues did not find an effect of gender on habituation (Hare et al., 2008). Similarly, in the present study, we did not find an effect of gender. As discussed in Reber & Tranel (2017), there is much work that needs to be done in order to understand how sex differences and neurological organization interact with other factors to influence emotion. Further, to truly evaluate the role of laterality, one needs to directly compare left and right amygdala function, to ensure that the two sides differ significantly as opposed to one side being under threshold and the other being above threshold. Future work should evaluate the extent to which UF facilitation of amygdala habituation is influenced by early life stress and impacts anxiety, whether there are unique effects by hemisphere of the brain, and whether any hemispheric effects differ by sex.

Beyond the primary hypothesis, a second objective of our study was to assess the potential moderation of the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala habituation by age, pubertal status, and gender. We found that pubertal status, but not age, moderated the association between left UF FA and left amygdala habituation to fearful faces. This finding held even when accounting for age. UF FA was more predictive of amygdala habituation in participants who were earlier in pubertal development relative to participants who were later in pubertal development. Increased strength of the relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation in participants who were earlier in pubertal development may be explained by slightly greater variability in amygdala habituation in participants who were earlier in pubertal development or may also be a function of hormonal changes that take place earlier in pubertal development. Early puberty may be a developmental period where structural connectivity of the UF is particularly important for emotion processing. However, we did not find that age moderated the association between limbic structure and function, as previous work has (Swartz et al., 2014). The age range of our sample was narrow (15–17 years); this enabled us to better evaluate the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala habituation in mid-adolescence, as well as the influence of puberty on this relation, but it did limit our ability to explore the influence of age. Another possibility supported by our findings is that pubertal status, not age, drives the age moderation of the relation between UF FA and amygdala activation found in prior work (Swartz et al., 2014). Further work is needed to parse the influences of age and pubertal status on brain structure and function development.

Finally, a third objective of our study was to better understand how age, gender, and pubertal status are related to amygdala habituation and UF structural connectivity. Inconsistent with our predictions, we did not find statistically significant relations between age, gender, pubertal status, and amygdala habituation, but this may be due to our conservative correction for multiple comparisons. Age was positively associated with right amygdala habituation, and pubertal status was positively associated with left amygdala habituation, but these findings did not survive comparison for multiple corrections. Similarly, as discussed above for our second objective, it is possible that this may be a function of the relatively narrow age range of our sample; perhaps we did not have enough variability in age to find an effect of age. It is possible that future work with greater variability in age and pubertal status may find statistically significant relations between these demographic variables and amygdala habituation, clarifying inconsistencies between our work and previous research. Age has been negatively associated with amygdala activation (Swartz et al., 2014), and pubertal status has been both positively (Moore et al., 2012) and negatively (Forbes et al., 2012) linked to amygdala activation. A second possibility is that differences in amygdala activation by age or pubertal status found in previous work were not necessarily a function of amygdala habituation; differences in mean amygdala activation over an entire task may be due to differences in amygdala habituation or differences in initial amygdala responsivity (Plichta et al., 2014). Future work examining the relations between age, pubertal status, and amygdala habituation may resolve differences between our work and previous research.

We also found that age, pubertal status, and gender did not relate to UF FA. These findings were inconsistent with our hypotheses and with previous work supporting a positive relation between age and UF FA (Hasan et al., 2009; Swartz et al., 2014). However, these findings may be a function of the relatively narrow age range of our sample (15–16.8 years) compared to Hasan et al. (2009) (7–68 years) and Swartz et al. (2014) (9.6–19.2 years). Future work utilizing a sample with a larger age range could clarify the inconsistencies between our current findings and previous work.

There were a number of limitations with the current study. One limitation is that due to the population-based sampling methodology used in the original FFCWS, a significant portion of our participants were not eligible to participate in MRI scanning. For example, 9 subjects had braces and 4 subjects were unable to fit in the scanner. Moreover, because we did not use weighting in our analyses, our findings cannot be seen as city, nor nationally representative. Second, due to the multi-modal neuroimaging approach, a greater number of participants had to be removed due to unusable DTI or fMRI data than if a single neuroimaging modality had been used. Despite these limitations, our sample size was more than double previous work exploring the relation between UF structural connectivity and amygdala reactivity. Further, our sample contained substantial representation of African American youth and families living in low SES contexts, populations often missing in neuroimaging research. A third limitation is that we failed to find statistically significant habituation in the left amygdala (the right amygdala did habituate). This null finding may be due to a relatively small number of trials (20) of each of the five emotions; a longer task or fewer emotions may yield better habituation results. Another possibility is that subgroups may habituate, sensitize, or experience no change in reactivity during the task; this will be examined in future work with this sample. Although habituation itself was not statistically significant, the degree to which a participant habituated was still predicted by left UF FA, meaning that although the sample did not demonstrate left amygdala habituation on the whole, individual differences in left UF FA predicted decreases in left amygdala responsivity during the course of the task. Despite these limitations, our work contributes to the field by improving upon prior work in three ways: 1) we examined amygdala habituation, a more reliable measure than amygdala activation (Gee et al. 2015) that is thought to index emotion regulation; 2) we used more advanced DTI methods; and 3) we recruited a large adolescent sample that was drawn from a population-based sample and included greater representation of understudied adolescents and families.

In conclusion, the current study identified a positive relation between UF FA and amygdala habituation in a large, well-sampled cohort of adolescents. Adolescents with greater UF white matter structural connectivity had more amygdala habituation, whereas adolescents with less UF white matter structural connectivity had less amygdala habituation. Additionally, pubertal status moderated this relation, such that the relation was stronger earlier in pubertal development. Only a few studies have linked structural and functional aspects of limbic circuitry, and this is the first to do so with habituation as well as specific demographic variables (puberty, age, and gender). By combining structural and functional neuroimaging, this study marks a key step toward a more comprehensive understanding of neural bases of socioemotional development.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, R01MH103761 (Monk), T32HD007109 (McLoyd & Monk), and S10OD012240 (Noll), as well as a Doris Duke Fellowship for the Promotion of Child Well-Being (Hein). We would also like to acknowledge the past work of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, the families for sharing their experiences with us, and the project staff for making the study possible.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baas D, Aleman A, & Kahn RS (2004). Lateralization of amygdala activation: a systematic review of functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Research Reviews, 45(2), 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks SJ, Eddy KT, Angstadt M, Nathan PJ, & Phan KL (2007). Amygdala–frontal connectivity during emotion regulation. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 2(4), 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H (2000). Connections underlying the synthesis of cognition, memory, and emotion in primate prefrontal cortices. Brain research bulletin, 52(5), 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ (2008). The social brain in adolescence. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 9(4), 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ (2012). Development of the social brain in adolescence. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 105(3), 111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Burnett S, & Dahl RE (2010). The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Human brain mapping, 31(6), 926–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, & Gargiulo J (1987). Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child development, 829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Bird G, Moll J, Frith C, & Blakemore SJ (2009). Development during adolescence of the neural processing of social emotion. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 21(9), 1736–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Sebastian C, Kadosh KC, & Blakemore SJ (2011). The social brain in adolescence: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging and behavioural studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(8), 1654–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, & Hare TA (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Dawson G (2002). Multiple levels of analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14(3), 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, & Dahl RE (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 13(9), 636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ (2002). Anxiety and affective style: role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biological psychiatry, 51(1), 68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detroit in Focus: A Profile from Census 2000. (2016, July 28). Retrieved June 14, 2018, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/detroit-in-focus-a-profile-from-census-2000/

- Falk EB, Hyde LW, Mitchell C, Faul J, Gonzalez R, Heitzeg MM, ... & Morrison FJ (2013). What is a representative brain? Neuroscience meets population science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(44), 17615–17622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Dahl RE, Almeida JR, Ferrell RE, Nimgaonkar VL, Mansour H, ... & Phillips ML (2012). PER2 rs2304672 polymorphism moderates circadian-relevant reward circuitry activity in adolescents. Biological psychiatry, 71(5), 451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Placentino A, Carletti F, Landi P, Allen P, Surguladze S, ... & Perez J (2009). Functional atlas of emotional faces processing: a voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience: JPN, 34(6), 418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván A, Van Leijenhorst L, & McGlennen KM (2012). Considerations for imaging the adolescent brain. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 2(3), 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, Gabard-Durnam LJ, Flannery J, Goff B, Humphreys KL, Telzer EH, ... & Tottenham N (2013). Early developmental emergence of human amygdala–prefrontal connectivity after maternal deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(39), 15638–15643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, McEwen SC, Forsyth JK, Haut KM, Bearden CE, Addington J, ... & Olvet D (2015). Reliability of an fMRI paradigm for emotional processing in a multisite longitudinal study. Human brain mapping, 36(7), 2558–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN (2008). The teen brain: insights from neuroimaging. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4), 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Vaituzis AC, Hamburger SD, Lange N, Rajapakse JC, Kaysen D, ... & Rapoport JL (1996). Quantitative MRI of the temporal lobe, amygdala, and hippocampus in normal human development: ages 4–18 years. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 366(2), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, ... & Rapoport JL (2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(21), 8174–8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther Moor B, Op de Macks ZA, Güroğlu B, Rombouts SA, Van der Molen MW, & Crone EA (2011). Neurodevelopmental changes of reading the mind in the eyes. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 7(1), 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Monk CS, McClure-Tone EB, Nelson EE, Roberson-Nay R, Adler AD, ... & Ernst M (2008). A developmental examination of amygdala response to facial expressions. Journal of Cognitive neuroscience, 20(9), 1565–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan KM, Iftikhar A, Kamali A, Kramer LA, Ashtari M, Cirino PT, ... & Ewing-Cobbs L (2009). Development and aging of the healthy human brain uncinate fasciculus across the lifespan using diffusion tensor tractography. Brain research, 1276, 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Tottenham N, Galvan A, Voss HU, Glover GH, & Casey BJ (2008). Biological substrates of emotional reactivity and regulation in adolescence during an emotional go-nogo task. Biological psychiatry, 63(10), 927–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Mattay VS, Tessitore A, Fera F, & Weinberger DR (2003). Neocortical modulation of the amygdala response to fearful stimuli. Biological psychiatry, 53(6), 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, & Gobbini MI (2002). Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biological psychiatry, 51(1), 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Pechaud M, & Smith S (2005, June). BET2: MR-based estimation of brain, skull and scalp surfaces. In Eleventh annual meeting of the organization for human brain mapping (Vol. 17, p. 167). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PE (2017). Rockchalk: Regression Estimation and Presentation. R package version 1.8.110. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rockchalk

- Jones DK, Knösche TR, & Turner R (2013). White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: the do’s and don’ts of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage, 73, 239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao UMA, Flynn C, Moreci P,…&Ryan N (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(10), 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, & Whalen PJ (2009). The structural integrity of an amygdala–prefrontal pathway predicts trait anxiety. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(37), 11614–11618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, & Giedd JN (2006). Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(6), 718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, & Burdette JH (2004). Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage, 21(1), 450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, & Burdette JH (2003). An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage, 19(3), 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson WI, Hein TC, Velasquez F, Peltier SJ, Lopez-Duran N, Mitchell C, Hyde LW, & Monk CS (under review). An emotional faces task that activates the amygdala and limits the effects of eye movement.

- McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair RJR, … Pine DS (2007). Abnormal Attention Modulation of Fear Circuit Function in Pediatric Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(1), 97 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae K, Gross JJ, Weber J, Robertson ER, Sokol-Hessner P, Ray RD, ... & Ochsner KN (2012). The development of emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 7(1), 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Klein RG, Telzer EH, Elizabeth Schroth BA, Salvatore Mannuzza B, Moulton III JL, … Ernst M (2008). Amygdala and Nucleus Accumbens Activation to Emotional Facial Expressions in Children and Adolescents at Risk for Major Depression. Am J Psychiatry, 1651 Retrieved from http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, McClure EB, Nelson EE, Zarahn E, Bilder RM, Leibenluft E, ... & Pine DS (2003). Adolescent immaturity in attention-related brain engagement to emotional facial expressions. Neuroimage, 20(1), 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Mai X, Louro HMC, … Pine DS (2008). Amygdala and Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex Activation to Masked Angry Faces in Children and Adolescents With Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(5), 568 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore III WE, Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Mazziotta JC, Iacoboni M, & Dapretto M (2012). Facing puberty: associations between pubertal development and neural responses to affective facial displays. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 7(1), 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S,Wakana S, Nagae-Poetscher L, & van Zijl PCM (2005). MRI Atlas of Human White Matter. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi MW, Cody-Hazlett H, Poe MD, Gerig G, Gimpel-Smith R, & Piven J (2009). Longitudinal study of amygdala volume and joint attention in 2-to 4-year-old children with autism. Archives of general psychiatry, 66(5), 509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Leibenluft E, McClure EB, & Pine DS (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: a neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological medicine, 35(02), 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EE, Jarcho JM, & Guyer AE (2015). Social re-orientation and brain development: an expanded and updated view. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 17, 118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M, Ohira H, Haneda K, Iidaka T, Sadato N, Okada T, & Yonekura Y (2004). Functional association of the amygdala and ventral prefrontal cortex during cognitive evaluation of facial expressions primed by masked angry faces: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage, 21(1), 352–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso MA, Glahn DC, Matsuo K, Monkul ES, Najt P, Zamarripa F, ... & Soares JC (2009). Amygdala hyperactivation in untreated depressed individuals. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 173(2), 158–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, & Boxer A (1988). A self-report measures of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(2), 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, & Allen NB (2012). Arrested development? Reconsidering dual-systems models of brain function in adolescence and disorders. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(6), 322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, & Blakemore SJ (2012). Adolescent social cognitive and affective neuroscience: past, present, and future. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer JH, Lieberman MD, & Dapretto M (2007). “I know you are but what am I?!”: neural bases of self-and social knowledge retrieval in children and adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(8), 1323–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Moore WE, Oswald TM, Mazziotta JC, Iacoboni M, & Dapretto M (2011). Entering adolescence: resistance to peer influence, risky behavior, and neural changes in emotion reactivity. Neuron, 69(5), 1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Fitzgerald DA, Nathan PJ, & Tancer ME (2006). Association between Amygdala Hyperactivity to Harsh Faces and Severity of Social Anxiety in Generalized Social Phobia. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Plichta MM, Grimm O, Morgen K, Mier D, Sauer C, Haddad L, ... & Meyer-Lindenberg A (2014). Amygdala habituation: a reliable fMRI phenotype. NeuroImage, 103, 383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin CH, Abrams T, Barry RJ, Bhatnagar S, Clayton DF, Colombo J, ... & McSweeney FK (2009). Habituation revisited: an updated and revised description of the behavioral characteristics of habituation. Neurobiology of learning and memory, 92(2), 135–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber J, & Tranel D (2017). Sex differences in the functional lateralization of emotion and decision making in the human brain. Journal of neuroscience research, 95(1–2), 270–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2001). Fragile families: Sample and design. Children and Youth Services Review, 23(4–5), 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team (2015). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc, Boston, MA: URL http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Scherf KS, Smyth JM, & Delgado MR (2013). The amygdala: an agent of change in adolescent neural networks. Hormones and behavior, 64(2), 298–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ, & Yuan W (2010). White matter development during adolescence as shown by diffusion MRI. Brain and cognition, 72(1), 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann CM, Hamstra J, Goodlin-Jones BL, Lotspeich LJ, Kwon H, Buonocore MH, ... & Amaral DG (2004). The amygdala is enlarged in children but not adolescents with autism; the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages. Journal of neuroscience, 24(28), 6392–6401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergerie K, Chochol C, & Armony JL (2008). The role of the amygdala in emotional processing: A quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 811–830. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, & Foster DL (2004). The neural basis of puberty and adolescence. Nature neuroscience, 7(10), 1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM (2002). Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human brain mapping, 17(3), 143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares J, Marques P, Alves V, & Sousa N (2013). A hitchhiker’s guide to diffusion tensor imaging. Frontiers in neuroscience, 7, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Fani N, & McClure-Tone EB (2011). Behavioral and neural representation of emotional facial expressions across the lifespan. Developmental neuropsychology, 36(4), 408–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, & Casey BJ (2010). A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, & Toga AW (2003). Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nature neuroscience, 6(3), 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Batth R, Jernigan TL, & Toga AW (1999). Localizing age-related changes in brain structure between childhood and adolescence using statistical parametric mapping. Neuroimage, 9(6), 587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP (2000). The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 24(4), 417–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberg JM, Jarcho JM, Dahl RE, Pine DS, Ernst M, & Nelson EE (2014). Anticipation of peer evaluation in anxious adolescents: divergence in neural activation and maturation. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 10(8), 1084–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Carrasco M, Wiggins JL, Thomason ME, & Monk CS (2014). Age-related changes in the structure and function of prefrontal cortex–amygdala circuitry in children and adolescents: A multi-modal imaging approach. Neuroimage, 86, 212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Phan KL, Angstadt M, Fitzgerald KD, & Monk CS (2014). Dynamic changes in amygdala activation and functional connectivity in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4 Pt 2), 1305–19. 10.1017/S0954579414001047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Wiggins JL, Carrasco M, Lord C, & Monk CS (2013). Amygdala habituation and prefrontal functional connectivity in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(1), 84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi AM, Artiges E, Banaschewski T, Barker GJ, Bruehl R, Büchel C, ... & Heinz A (2012). Creating probabilistic maps of the face network in the adolescent brain: a multicentre functional MRI study. Human brain mapping, 33(4), 938–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason ME, Dougherty RF, Colich NL, Perry LM, Rykhlevskaia EI, Louro HM, ... & Gotlib IH (2010). COMT genotype affects prefrontal white matter pathways in children and adolescents. Neuroimage, 53(3), 926–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason ME, & Thompson PM (2011). Diffusion imaging, white matter, and psychopathology. Annual review of clinical psychology, 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, & Sheridan MA (2009). A review of adversity, the amygdala and the hippocampus: a consideration of developmental timing. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare TA, ... & Nelson C (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry research, 168(3), 242–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromp DP, Grupe DW, Oathes DJ, McFarlin DR, Hernandez PJ, Kral TR, ... & Nitschke JB (2012). Reduced structural connectivity of a major frontolimbic pathway in generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 69(9), 925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, ... & Joliot M (2002). Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage, 15(1), 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa RA, Pine DS, Thorn JM, Nelson TE, Spinelli S, Nelson E, ... & Mostofsky SH (2011). Enhanced right amygdala activity in adolescents during encoding of positively valenced pictures. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 1(1), 88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Der Heide RJ, Skipper LM, Klobusicky E, & Olson IR (2013). Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain, 136(6), 1692–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Phan KL, Liberzon I, & Taylor SF (2003). Valence, gender, and lateralization of functional brain anatomy in emotion: a meta-analysis of findings from neuroimaging. Neuroimage, 19(3), 513–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JL, Swartz JR, Martin DM, Lord C, & Monk CS (2013). Serotonin transporter genotype impacts amygdala habituation in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 9(6), 832–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]