Abstract

Depression is one of the most common mood disorders with a high rate of relapse. Accumulating evidence suggests that the transcription factor Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived protein with CNC homology (ECH)-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) system plays a key role in inflammation which is involved in depression. Preclinical studies demonstrated that the protein expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) of hippocampus in mice with depression-like phenotype were lower than control mice. In the learned helplessness paradigm, the protein levels of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the PFC and DG of hippocampus from rats with depression-like phenotype were also lower than control and resilient rats. Furthermore, rodents with depression-like phenotype have higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, Nrf2 knock-out (KO) mice exhibit depression-like phenotype, and higher serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared with wild-type mice. Furthermore, Nrf2 KO mice have lower expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the PFC, and CA3 and DG of hippocampus compared to wild-type mice. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone, a TrkB agonist, showed antidepressant effects in Nrf2 KO mice, by stimulating BDNF-TrkB in the PFC, CA3, and DG. Pretreatment with sulforaphane, a naturally occurring Nrf2 activator, prevented depression-like phenotype in mice after inflammation, or chronic social defeat stress. Interestingly, dietary intake of 0.1% glucoraphanin (a precursor of sulforaphane) containing food during juvenile and adolescent stages of mice could prevent depression-like phenotype in adulthood after chronic social defeat stress. Moreover, the protein expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the parietal cortex from major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder were lower than controls. These findings suggest that Keap1-Nrf2 system plays a key role in the stress resilience which is involved in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. It is, therefore, possible that dietary intake of cruciferous vegetables including glucoraphanin (or SFN) may prevent or minimize relapse from remission, induced by stress and/or inflammation in depressed patients. In the review, the author would like to discuss the role of Keap1-Nrf2 system in mood disorders.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, glucoraphanin, keap1, Nrf2, nutrition, stress resilience, sulforaphane, TrkB

Introduction

Depression, one of the most common psychiatric disorders in the world, is a mood disorder with a high rate of relapse. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 320 million individuals of all ages suffer from depression, highlighting this disease as a major contributor to the global burden of disease (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). Although the precise mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of depression are currently unknown, accumulating evidence implicate inflammatory processes in the pathophysiology of depression (Dantzer et al., 2008; Hashimoto, 2009; Miller et al., 2009; Raison et al., 2010; Hashimoto, 2015; Mechawar and Savitz, 2016; Miller and Raison, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2017). Meta-analysis demonstrated higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood of drug-free or medicated depressed patients compared to healthy controls (Dowlati et al., 2010; Young et al., 2014; Haapakoski et al., 2015; Köhler et al., 2018). Studies demonstrated elevated gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the postmortem brain samples from patients with a history of depression (Dean et al., 2010; Shelton et al., 2011). Collectively, it is likely that inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology of depression.

Over the past decade, there has been increasing interest in the potential benefits of early intervention for mood disorders. Several lines of evidence suggest that nutrition has a high impact on the development of depression (Lin et al., 2010; Murakami and Sasaki, 2010; Bazinet and Layé, 2014; Mello et al., 2014; El-Behadli et al., 2015; Opie et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). Recent meta-analyses demonstrated that high intake of fruit, vegetables, fish, and whole grains are associated with a lower risk of depression (Lai et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Saghafian et al., 2018).

In the review, the author would like to discuss the role of Keap1 [Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived protein with CNC homology [ECH]-associated protein 1)]-Nrf2 [Nuclear factor (erythroid 2-derived)-like 2] system in the pathophysiology of depression since Keap1-Nrf2 system plays a key role in inflammation. Furthermore, we also refer to the clinical significance of natural Nrf2 activator sulforaphane (SFN) as nutritional intervention for mood disorders.

Keap1-Nrf2 System

Nrf2 is the transcription factor with a key role in cellular defense against oxidative stress. It binds to the antioxidant response elements (ARE) located in the promoter region of genes encoding many phase II detoxifying or antioxidant enzymes and related stress-responsive proteins (Kobayashi et al., 2013; Ma, 2013; Suzuki et al., 2013a; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015; Yamamoto et al., 2018). Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is repressed by Keap1, which is an adaptor protein for the degradation of Nrf2 (Suzuki et al., 2013a; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015). During oxidative stress, Nrf2 is de-repressed and activates the transcription of protective genes (Suzuki et al., 2013a; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015). Importantly, the Keap1-Nrf2 system plays a role in inflammation-associated pathogenesis (Kobayashi et al., 2013; Suzuki et al., 2013a; O’Connell and Hayes, 2015; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015; Wardyn et al., 2015; Yamamoto et al., 2018). In cancer cells, Nrf2 activation is beneficial and deleterious for the cancer-bearing host, depending on the time (initiation, promotion, and metastasis) and place (cancer cells or microenvironment) (Yamamoto et al., 2018).

Nrf2 Activators

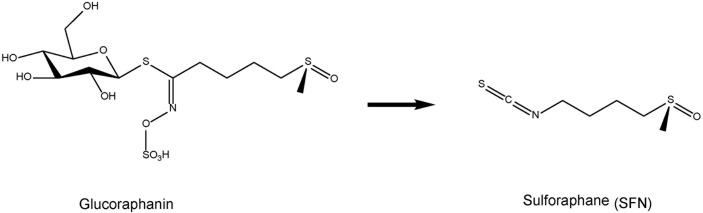

Based on the role of Nrf2 in the prevention of a wide variety of pathological conditions, great efforts have been made to isolate from natural sources or develop potent and specific Nrf2 activators (Yamamoto et al., 2018). The potent anti-inflammatory and naturally occurring compound sulforaphane (SFN: 1-isothiocyanato-4-methylsulfinylbutane) is an organosulfur compound derived from a glucosinolate precursor glucoraphanin (a glucosinolate, or β-thioglucoside-N-hydroxysulfate) (Figure 1) found in cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli sprout (Zhang et al., 1992; Fahey et al., 1997; Kwak and Kensler, 2010; Kensler et al., 2013; Fahey et al., 2015). It is well known that glucoraphanin can be converted to SFN by the endogenous enzyme, myrosinase (Fahey et al., 2015). Beneficial effect by SFN is thought to be mediated via activation of the Nrf2 pathway with subsequent up-regulation of phase II detoxification enzymes and antioxidant proteins, through ARE (Suzuki et al., 2013a; Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015).

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure of sulphoraphane (SFN) and its precursor glucoraphanin. Cruciferous vegetables contain glucoraphanin, a glucosinolate derivative of sulforaphane (SFN).

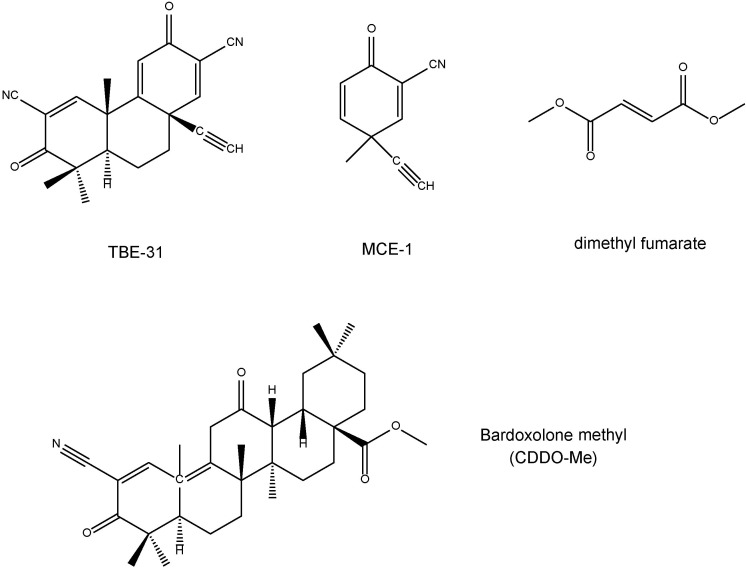

TBE-31 [(±)-(4bS,8aR,10aS)-10a-ethynyl-4b,8,8-trimethyl-3,7-dioxo-3,4b,7,8,8a,9,10,10a-octahydrophenanthrene-2,6-dicarbonitrile] and MCE-1 [(±)-3-ethynyl-3-methyl-6-oxocyclohexa-1,4-dienecarbonitrile] are the novel Nrf2 activators (Honda et al., 2007; Dinkova-Kostova et al., 2010; Honda et al., 2011; Kostov et al., 2015; Figure 2). Dimethyl fumarate (Figure 2) is a new oral drug for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, and has neuroprotective effects via Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response (Al-Jaderi and Maghazachi, 2016; Mills et al., 2018). Bardoxolone methyl, the C-28 methyl ester of 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid (CDDO) known as CDDO-Me (Figure 2), is one of the derivatives of synthetic triterpenoids. Bardoxolone methyl has been used for the treatment of cancer (including leukemia and solid tumors), chronic kidney disease, and other diseases (Wang et al., 2014). Clinical trial of bardoxolone methyl is undergoing for diabetic nephropathy in Japan (Yamamoto et al., 2018), although its development was paused in the United States due to the occurrence of cardiac complications in patients with end-stage renal disease (Pergola et al., 2011; de Zeeuw et al., 2013).

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structure of Nrf2 activators (TBE-31, MCE-1, dimethyl fumarate, bardoxolone methyl).

Effects of Nrf2 Activators on Neurite Outgrowth

The neuronal plasticity, including neurite outgrowth and neuroprotection, plays crucial role in the beneficial effect of therapeutic drugs in cellular level (Lu and Dwyer, 2005; Williams and Dwyer, 2009). Yao et al. (2016b) reported that SFN increased the number of cell with neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Furthermore, the potentiating effects of SFN on NGF-induced neurite outgrowth were blocked by treatment with Nrf2 siRNA, but not the negative control (Yao et al., 2016b), suggesting that SFN can potentiate NGF-induced neurite outgrowth via activation of Nrf2.

Yao et al. (2016a) reported that TBE-31 and MCE-1 also potentiated NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. The Nrf2 siRNA blocked the potentiating effects of TBE-31 and MCE-1 on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Astragaloside IV is also reported to attenuate lead-induced inhibition of neurite outgrowth through activation of Akt-dependent Nrf2 pathway (Yu et al., 2017). Collectively, it is likely that Nrf2 activators can promote neurite outgrowth through Nrf2 activation (Yang et al., 2015c; Yao et al., 2016a,b).

Alterations in Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling in Rodents with Depression-Like Phenotype

Chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) model has been used widely as an animal model of depression (Krishnan and Nestler, 2008; Nestler and Hyman, 2010; Golden et al., 2011). Susceptible mice with depression-like phenotype after CSDS have higher blood levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, and IL-1β] (Zhang et al., 2017a).

Western blot analysis showed that protein levels of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the CA3, DG, and PFC from mice with depression-like phenotype were significantly lower than those of control mice (Yao et al., 2016b). In contrast, protein levels of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the CA1 and NAc were not different compared to control (Yao et al., 2016b). These findings suggest that lower levels of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the CA3, DG, and PFC may be involved in depression-like phenotypes after CSDS.

Learned helplessness (LH) model has been also used as an animal model of depression (Krishnan and Nestler, 2008). In the LH paradigm, approximately 20–40% rats are resilient to inescapable stress (Yang et al., 2015a,b; Yang et al., 2016). LH (susceptible) rats have higher blood levels of IL-6 than control and resilient rats (Yang et al., 2015a), suggesting that peripheral inflammation may contribute to resilience versus susceptibility to stress. Protein levels of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the PFC and DG of hippocampus from LH (susceptible) rats were lower than control and non-LH (resilient) rats (Zhang et al., 2018). These results suggest that Keap1-Nrf2 signaling may contribute to stress resilience which is involved in the pathophysiology of major psychiatric disorders (Zhang et al., 2018).

Alterations in Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling in Samples from Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) patients (n = 30) exhibited higher levels of Nrf2 and its regulator Keap1, as well as NF-κB in the cytoplasm of peripheral blood mononuclear cells compared to healthy controls (n = 35), suggesting that depression may be characterized by up-regulation of the transcription factor Keap1-Nrf2 (Lukic et al., 2014). Using genome-wide transcriptional profiling and promoter-based bioinformatic strategies, Mellon et al. (2016) measured leukocyte transcription factor (TF) activity in leukocytes from un-medicated MDD subjects (n = 20) versus age- and sex-matched healthy controls (n = 20). In leukocytes from un-medicated MDD subjects, the bioinformatic analysis showed an increased transcriptional activity of cAMP response element-binding/activating TF (CREB/ATF) and increased activity of TFs associated with Nrf2. Antidepressant therapy for 8 weeks was associated with significant reductions in depressive symptoms and reduced activity of Nrf2, but not in CREB/ATF activity. By contrast, other transcriptional regulation pathways, including nuclear factor kappa-B cells (NF-κB), early growth response proteins 1-4 (EGR1-4), the glucocorticoid receptor, and interferon-responsive TFs, showed either no difference as a function of disease or treatment. These results suggest that Nrf2 signaling may contribute to MDD by activating immune cell transcriptome dynamics that ultimately may influence motivational and affective processes via circulating mediators (Mellon et al., 2016).

Postmortem tissue from patients with psychiatric disorders is an underutilized substance that may be used to translate genetic and/or preclinical studies (Hashimoto et al., 2007; McCullumsmith et al., 2013; Mechawar and Savitz, 2016; Yang et al., 2017). A study using postmortem brain samples showed decreased expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the parietal cortex from patients with MDD and bipolar disorder compared to control group (Zhang et al., 2018). A recent study showed the reduced (-21%) expression of Nrf2 in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex from MDD patients (Martín-Hernández et al., 2018). These results suggest that decreased Keap1-Nrf2 signaling plays a key role in the pathophysiology of mood disorders such as MDD and bipolar disorder (Zhang et al., 2018).

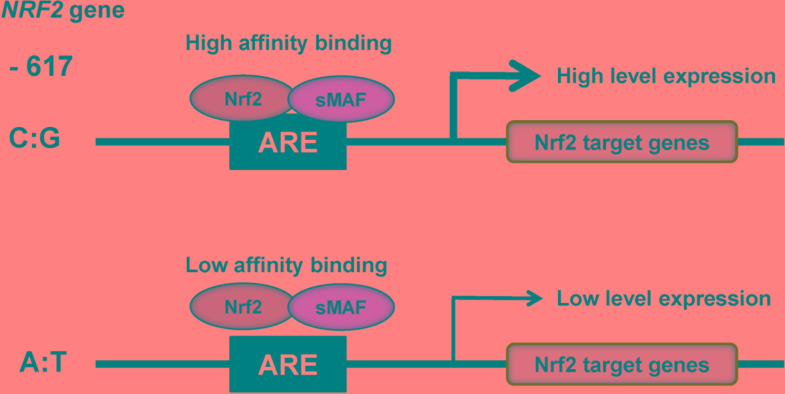

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Nrf2 Promoter Gene in Humans

The NRF2 activity in humans is regulated through protein stabilization, primarily by KEAP1, but is also regulated at the transcriptional level (Yamamoto et al., 2018). In humans, a NRF2 promotor single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP: rs6721961) located 617 bp by upstream from the transcription start site lowers the level of NRF2 transcription (Yamamoto et al., 2006; Yamamoto et al., 2018; Figure 3). Luciferase assays showed that polymorphism at position -617 (C to A) affect basal levels of NRF2, thereby resulting in attenuation of ARE-mediated gene transcription (Marzec et al., 2007; Figure 3). Interestingly, subjects who possess this SNP are more susceptible to acute lung injury and related diseases (Marzec et al., 2007), and this SNP is also found to correlate with the incidence of non-small cell lung cancer (Suzuki et al., 2013b). In addition, ethnic difference of this SNP is also reported (Marzec et al., 2007). Therefore, it is of interest to study whether this SNP can affect susceptibility to mood disorders.

FIGURE 3.

SNP (rs6721961) in the promotor region of NRF2 gene. The SNP (rs6721961) in the promotor of NRF2 gene alters the transcription level of NRF2 gene, resulting in alterations in the expression of NRF2 target genes. The NRF2/sMAF (small MAF) protein complex regulates the oxidative stress response by occupying cis-acting enhancers containing an antioxidant response element (ARE). A slight modification of Yamamoto et al. (2018).

Depression-Like Phenotypes in Nrf2 KO Mice

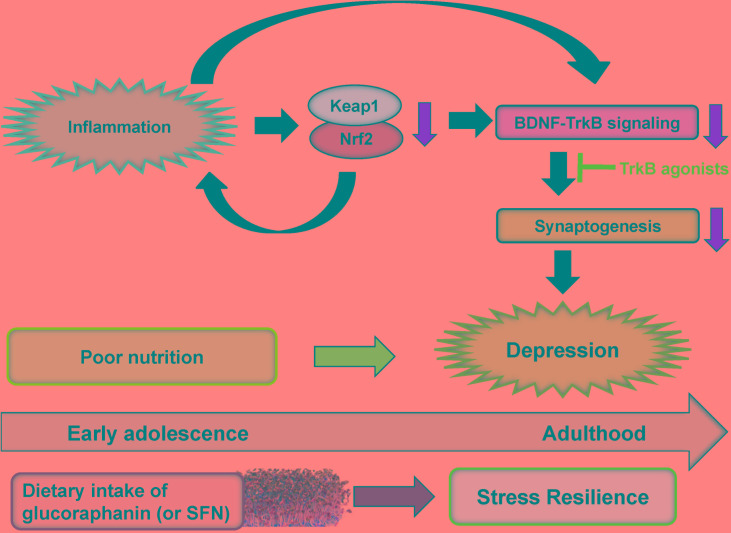

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1β in the Nrf2 KO mice were significantly higher than those of wild-type (WT) mice, suggesting that Nrf2 KO mice have inflammation (Yao et al., 2016b). In the tail-suspension test (TST) and forced swimming test (FST), the immobility times of TST and FST in Nrf2 KO mice were higher than those of WT mice. In the 1% sucrose preference test (SPT), the sucrose preference of Nrf2 KO mice was lower than that of WT mice, suggesting that Nrf2 KO mice have anhedonia. Furthermore, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor TrkB signaling in the CA3, DG and PFC of Nrf2 KO mice were lower than those of WT mice. Moreover, protein levels of AMPA receptor 1 (GluA1) and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95) in the CA3, DG, and PFC of KO mice were lower than those of WT mice. Interestingly, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (a TrkB agonist) produced antidepressant effects in Nrf2 KO mice, by stimulating TrkB in the PFC, CA3, and DG (Yao et al., 2016b). Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory drug rofecoxib reversed depression-like behaviors in Nrf2 KO mice (Martín-de-Saavedra et al., 2013). In addition, chronic treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) fluoxetine increased BDNF in cortex and hippocampus of corticosterone-treated Nrf2 KO mice (Mendez-David et al., 2015), suggesting that Nrf2 signaling contributes to fluoxetine-induced neuroprotection. These all findings suggest that Nrf2 plays a key role in the depression-like phenotypes in rodents through potent anti-inflammatory action. Collectively, it is likely that Nrf2 KO mice show depression-like phenotypes through inflammation, decreased BDNF-TrkB signaling and synaptogenesis (Figure 5; Yao et al., 2016b).

FIGURE 5.

Proposed hypothesis of role of Keap1-Nrf2 system in depression. Inflammation causes decreases of Keap1 and Nrf2 expression in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Subsequently, inflammation-induced decreases in Keap1 and Nrf2 proteins can cause the decreased BDNF-TrkB signaling and synaptogenesis, resulting in depression-like phenotype. TrkB agonists might have antidepressant actions. Dietary intake of glucoraphanin (or SFN) in cruciferous vegetables during early adolescence may confer to stress resilience at adulthood whereas poor nutrition may play a role in the onset of depression by stress or inflammation.

In contrast, Bouvier et al. (2017) reported that Nrf2 KO mice did not display a depression-like phenotype although the KO mice were characterized by oxidative stress and by anatomical alterations in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells. However, when exposed to 3 weeks of chronic mild stress, Nrf2 KO mice developed depression-like phenotypes which were prevented by pretreatment with antioxidant (Bouvier et al., 2017). This study also suggests the role of Nrf2-dependent persistent oxidative stress in stress-induced vulnerability to depression.

Antidepressant Effects of Nrf2 Activators in the Rodent Models of Depression

When lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the bacterial endotoxin, is administered to rodents, depression-like behaviors are observed 24 h after inflammation (Dantzer et al., 2008; O’Connor et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2016). Pretreatment with antidepressants, such as SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), can prevent depression-like behavior and alterations in serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, induced by LPS administration (Ohgi et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2016). These all findings suggest that inflammation is associated with depression, and that anti-inflammatory drugs could ameliorate depressive symptoms in patients with depression.

Pretreatment with SFN significantly blocked an increase in the serum TNF-α level after a single administration of LPS (Zhang et al., 2017b). Furthermore, SFN significantly potentiated increased serum levels of IL-10 after LPS administration. SFN attenuated an increase of the immobility time of TST and FST after LPS administration. In addition, SFN recovered to control levels for LPS-induced alterations in the proteins such as BDNF, PSD-95 and GluA1, and dendritic spine density in the brain regions (Zhang et al., 2017b). Furthermore, TBE-31 or MCE-1 attenuated an increase in serum levels of TNF-α after LPS administration. Administration of TBE-31 or MCE-1 attenuated an increase in the immobility time of TST and FST after LPS administration (Yao et al., 2016a).

Pretreatment with SFN attenuated the decreased social avoidance time and sucrose preference in CSDS model. Furthermore, SFN could attenuate the decreased levels of Nrf2 and Keap1 proteins in the PFC and hippocampus of mice with depression-like phenotype (Yao et al., 2016b). Li et al. (2018) reported that decreased Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in the PFC, hippocampus and skeletal muscle may contribute to anhedonia susceptibility after spared nerve injury (SNI), and that SFN exerts beneficial effects in SNI rats by normalization of decreased Keap1-Nrf2 signaling. These results suggest that Keap1-Nrf2 signaling plays a role in depression, and that SFN is prophylactic compound which can stimulate Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway (Yao et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2017b; Li et al., 2018). Taken all together, it is likely that the Nrf2 activators such as SFN, TBE-31, and MCE-1 might be potential prophylactic or therapeutic drugs for inflammation (or stress)-related depression (Yao et al., 2016a,b; Zhang et al., 2016, 2017b; Li et al., 2018).

Effects of Dietary Intake of SFN Precursor in the CSDS Model of Depression

SFN is produced in the body from its precursor glucoraphanin which is involved in cruciferous vegetables. Previously, we demonstrated that dietary intake of 0.1% glucoraphanin –rich food during juvenile and adolescence prevented phencyclidine-induced cognitive deficits and loss of parvalbumin (PV)-positive cells in the PFC at adulthood (Shirai et al., 2015). Furthermore, we also reported that dietary intake of 0.1% glucoraphanin –rich food during juvenile and adolescence prevented the onset of psychosis in the adult offspring after maternal immune activation (Matsuura et al., 2018). These findings suggest that dietary-intake of glucoraphanin-rich vegetables in high-risk psychosis subjects might prevent the transition to psychosis in young adulthood (Hashimoto, 2014; Shirai et al., 2015; Matsuura et al., 2018).

Interestingly, dietary intake of 0.1% glucoraphanin containing food during juvenile and adolescent stages could prevent the depression-like phenotype in adulthood after CSDS (Yao et al., 2016b). Thus, the dietary intake of 0.1% glucoraphanin containing food during juvenile and adolescent periods could confer stress resilience in adulthood.

Clinical Study of SFN in Patients with Healthy Subjects, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Sedlak et al. (2018) reported that SFN increased blood glutathione (GSH) levels in healthy human subjects following 7 days of daily oral administration. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation between blood and thalamic GSH post- and pre-SFN treatment ratios was observed, in addition to a consistent increase in brain GSH levels in response to treatment. This study suggests the value of exploring relationships between peripheral GSH and clinical/neuropsychological measures, as well as the influences SFN has on functional measures that are altered in neuropsychiatric disorders.

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study showed that SFN-rich broccoli sprout extract could improve social interaction, abnormal behavior and verbal communication in young male subjects with autism spectrum disorder (Singh et al., 2014; Lynch et al., 2017). In addition, a pilot study showed that supplementation with glucoraphanin-rich broccoli sprout extract for 8 weeks was effective in treating cognitive impairment in medicated patients with schizophrenia (Shiina et al., 2015). Collectively, it is likely that SFN would be potential therapeutic compound for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Role of Nrf2 in the Mechanisms of Antidepressant Action for Other Potential Compounds

Cilostazol is used in the treatment of the symptoms of intermittent claudication in patients with peripheral vascular disease. In the chronic restraint stress (CRS) model, cilostazol prevented depressive-like behaviors (Abuelezz and Hendawy, 2018). Furthermore, cilostazol modulated the Nrf2 protein and heme oxygenase-1 and NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase-1 gene expression in the hippocampus of CRS rats. These findings suggest that cilostazol has the prophylactic antidepressant effect by preventing oxidative stress by stimulation of redox defense mechanisms mediated through the Nrf2 pathway (Abuelezz and Hendawy, 2018).

Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide (NBP), a small molecule compound extracted from the seeds of Apium graveolens, was approved by the State Food and Drug Administration of China for treating ischemic stroke (Abdoulaye and Yi, 2016). NBP attenuated the depression-like behaviors and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β and IL-6) in rats. In addition with the anti-inflammation action, NBP reduced LPS-induced oxidative stress reactions in the hippocampus and enhanced Nrf2-targeted signals (Yang et al., 2018).

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that NBP showed greater effects than placebo on Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) and clinician’s interview-based impression of change plus caregiver input (CIBIC-plus). NBP-related adverse events were uncommon and primarily consisted of mild gastrointestinal symptoms (Jia et al., 2016). Therefore, it is of interest to examine whether NBP can improve depressive symptoms in depressed patients.

Nrf2 Inhibitors

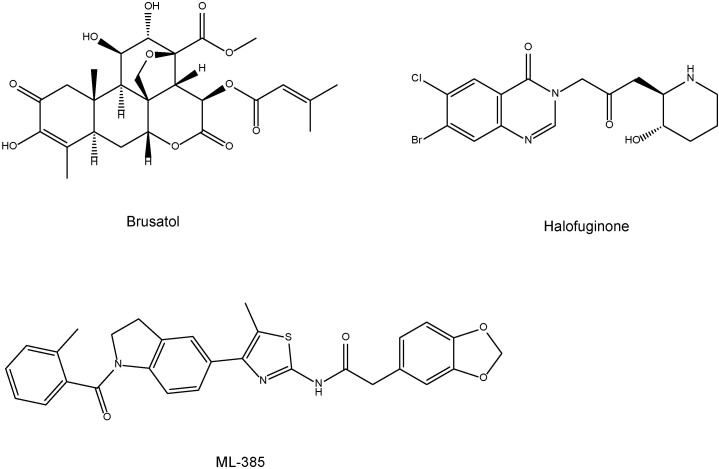

Compared with Nrf2 activators, the development of Nrf2 inhibitors is in its infancy (Yamamoto et al., 2018). For example, cancers with persistent activation of Nrf2 exhibit high dependency on Nrf2 function for drug resistance and cell proliferation (Yamamoto et al., 2018). The plant-based product brusatol (Figure 4) decreases the protein levels of Nrf2 and sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Ren et al., 2011). Another Nrf2 inhibitor halofuginone (Figure 4) is a synthetic halogenated derivative of febrifugine, a natural quinazolinone alkaloid which can be found in the Chinese herb Dichroa febrifuga. Halofuginone exerts a chemosensitizing effect on cancer cells exhibiting constitutive Nrf2 stabilization (Tsuchida et al., 2017). In addition, Singh et al. (2016) demonstrated that ML385 [N-[4-[2,3-dihydro-1-(2-methylbenzoyl)-1H-indol-5-yl]-5-methyl-2-thiazolyl]-1,3-benzodioxole-5-acetamide] (Figure 4) is a novel and specific Nrf2 inhibitor. Therefore, it is of interest to study whether these Nrf2 inhibitors can affect depression-like phenotypes in rodents.

FIGURE 4.

Chemical structure of Nrf2 inhibitors (brustal, halofuginone, ML-385).

Conclusion Remarks and Future Perspective

Rodents with depression-like phenotype have higher blood levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that inflammation plays a role in depression-like phenotype in rodents. Furthermore, rodents with depression-like phenotype have lower expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the PFC and hippocampus (Yao et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2017b). Interestingly, we found decreased expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the parietal cortex from patients with MDD and bipolar disorder (Zhang et al., 2018). Given the essential role of BDNF-TrkB signaling in depression (Nestler et al., 2002; Hashimoto et al., 2004; Duman and Monteggia, 2006; Hashimoto, 2010; Zhang et al., 2016), inflammation (or stress)-induced reduction of Keap1-Nrf2 system may contribute to decreased BDNF-TrkB signaling and synaptogenesis, resulting in depression-like phenotypes (Figure 5). It is noteworthy that TrkB agonist 7,8-DHF has antidepressant effects in Nrf2 KO mice (Yao et al., 2016b), LPS-treated mice (Zhang et al., 2014) and CSDS susceptible mice (Zhang et al., 2015), suggesting a possible link between Keap1-Nrf2 system and BDNF-TrkB signaling (Mendez-David et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2017b; Li et al., 2018; Figure 5).

Nutritional status during early adolescence stage might have a great impact on the onset and severity of psychiatric diseases in adulthood (Paus et al., 2008; O’Connor and Cryan, 2014). Over the past decade, there has been increasing interest in the potential benefits of early intervention for psychiatric disorders such as depression (Paus et al., 2008; O’Connor and Cryan, 2014; Sarris et al., 2015; Correll et al., 2018).

Preclinical findings suggest that dietary intake of glucoraphanin during juvenile and adolescence can protect against depression-like behaviors after CSDS or LPS administration (Yao et al., 2016b; Zhang et al., 2017b), indicating prophylactic effects of glucoraphanin for depression. Thus, dietary intake of glucoraphanin (or SFN) during juvenile and adolescence might confer stress resilience at adulthood (Figure 5). Therefore, it is possible that dietary intake of glucoraphanin (or SFN) during childhood and adolescence stages could prevent the onset of depression in humans during adulthood. Since patients with mood disorder have high relapse rate, dietary intake of glucoraphanin (or SFN) may prevent or minimize relapse from remission, induced by inflammation and/or stress in depressed patients.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my collaborators who are listed as the co-authors of our papers in the reference list.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by grants from JSPS KAKENHI (to KH, 17H04243), and AMED, Japan (to KH, JP18dm0107119).

References

- Abdoulaye I. A., Yi J. G. (2016). A review of recent advances in neuroprotective potential of 3-N-butylphthalide and its derivatives. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016:5012341. 10.1155/2016/5012341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuelezz S. A., Hendawy N. (2018). Insights into the potential antidepressant mechanisms of cilostazol in chronically restraint rats: impact on the Nrf2 pathway. Behav. Pharmacol. 29 28–40. 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaderi Z., Maghazachi A. A. (2016). Utilization of dimethyl fumarate and related molecules for treatment of multiple sclerosis, cancer, and other diseases. Front. Immunol. 7:278. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet R. P., Layé S. (2014). Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 771–785. 10.1038/nrn3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier E., Brouillard F., Molet J., Claverie D., Cabungcal J. H., Cresto N., et al. (2017). Nrf2-dependent persistent oxidative stress results in stress-induced vulnerability to depression. Mol. Psychiatry 22 1701–1713. 10.1038/mp.2016.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll C. U., Galling B., Pawar A., Krivko A., Bonetto C., Ruggeri M., et al. (2018). Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 75 555–565. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O’Connor J. C., Freund G. G., Johnson R. W., Kelley K. W. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 46–57. 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zeeuw D., Akizawa T., Audhya P., Bakris G. L., Chin M., Christ-Schmidt H., et al. (2013). Bardoxolone methyl in type 2 diabetes and stage 4 chronic kidney disease. N. Eng. J. Med. 369 2492–2503. 10.1056/NEJMoa1306033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B., Tawadros N., Scarr E., Gibbons A. S. (2010). Regionally-specific changes in levels of tumour necrosis factor in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex obtained postmortem from subjects with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 120 245–248. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Talalay P., Sharkey J., Zhang Y., Holtzclaw W. D., Wang X. J., et al. (2010). An exceptionally potent inducer of cytoprotective enzymes: elucidation of the structural features that determine inducer potency and reactivity with Keap1. J. Biol. Chem. 285 33747–33755. 10.1074/jbc.M110.163485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C., Zhang J. C., Yao W., Ren Q., Yang C., Ma M., et al. (2016). Effects of escitalopram, R-citalopram, and reboxetine on serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-10, and depression-like behavior in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 144 7–12. 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y., Herrmann N., Swardfager W., Liu H., Sham L., Reim E. K., et al. (2010). A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 67 446–457. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R. S., Monteggia L. M. (2006). A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 59 1116–1127. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Behadli A. F., Sharp C., Hughes S. O., Obasi E. M., Nicklas T. A. (2015). Maternal depression, stress and feeding styles: towards a framework for theory and research in child obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 113 S55–S71. 10.1017/S000711451400333X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey J. W., Holtzclaw W. D., Wehage S. L., Wade K. L., Stephenson K. K., Talalay P. (2015). Sulforaphane bioavailability from glucoraphanin-rich broccoli: control by active endogenous myrosinase. PLoS One 10:e0140963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey J. W., Zhang Y., Talalay P. (1997). Broccoli sprouts: an exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 10367–10372. 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden S. A., Covington H. E., Berton O., Russo S. J. (2011). A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat. Protoc. 6 1183–1191. 10.1038/nprot.2011.361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haapakoski R., Mathieu J., Ebmeier K. P., Alenius H., Kivimäki M. (2015). Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 49 206–215. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2009). Emerging role of glutamate in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Brain Res. Rev. 61 1056–1123. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2010). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a biomarker for mood disorders: an historical overview and future directions. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 64 341–357. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2014). Targeting of NMDA receptors in new treatments for schizophrenia. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 18 1049–1063. 10.1517/14728222.2014.934225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2015). Inflammatory biomarkers as differential predictors of antidepressant response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 7796–7801. 10.3390/ijms16047796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Sawa A., Iyo M. (2007). Increased levels of glutamate in brains from patients with mood disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 62 1310–1316. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Shimizu E., Iyo M. (2004). Critical role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in mood disorders. Brain Res. Rev. 45 104–114. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda T., Sundararajan C., Yoshizawa H., Su X., Honda Y., Liby K. T., et al. (2007). Novel tricyclic compounds having acetylene groups at C-8a and cyano enones in rings A and C: highly potent anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective agents. J. Med. Chem. 50 1731–1734. 10.1021/jm070141c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda T., Yoshizawa H., Sundararajan C., David E., Lajoie M. J., Favaloro F. G., Jr., et al. (2011). Tricyclic compounds containing nonenolizable cyano enones: a novel class of highly potent anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective agents. J. Med. Chem. 54 1762–1778. 10.1021/jm101445p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M. C., Tung C. Y., Chen H. E. (2018). Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in prevention and treatment of maternal depression: putative mechanism and recommendation. J. Affect. Disord. 238 47–61. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J., Wei C., Liang J., Zhou A., Zuo X., Song H., et al. (2016). The effects of DL-3-n-butylphthalide in patients with vascular cognitive impairment without dementia caused by subcortical ischemic small vessel disease: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 12 89–99. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensler T. W., Egner P. A., Agyeman A. S., Visvanathan K., Groopman J. D., Chen J. G., et al. (2013). Keap1-Nrf2 signaling: a target for cancer prevention by sulforaphane. Top Curr. Chem. 329 163–177. 10.1007/128_2012_339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi E., Suzuki T., Yamamoto M. (2013). Roles Nrf2 plays in myeloid cells and related disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:529219. 10.1155/2013/529219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C. A., Freitas T. H., Stubbs B., Maes M., Solmi M., Veronese N., et al. (2018). Peripheral alterations in cytokine and chemokine levels after antidepressant drug treatment for major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 4195–4206. 10.1007/s12035-017-0632-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostov R. V., Knatko E. V., McLaughlin L. A., Henderson C. J., Zheng S., Huang J. T., et al. (2015). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of orally administered acetylenic tricyclic bis(cyanoenone), a highly potent Nrf2 activator with a reversible covalent mode of action. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 465 402–407. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V., Nestler E. J. (2008). The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 455 894–902. 10.1038/nature07455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak M. K., Kensler T. W. (2010). Targeting NRF2 signaling for cancer chemoprevention. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 244 66–76. 10.1016/j.taap.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J. S., Hiles S., Bisquera A., Hure A. J., McEvoy M., Attia J. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99 181–197. 10.3945/ajcn.113.069880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Yang C., Fang X., Zhan G., Huang N., Gao J., et al. (2018). Role of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in anhedonia symptoms in a rat model of chronic neuropathic pain: improvement with sulforaphane. Front. Pharmacol. 9:887. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. Y., Chang C. H., Chong M. F., Chen H., Su K. P. (2017). Polyunsaturated fatty acids in perinatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 82 560–569. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.02.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P. Y., Huang S. Y., Su K. P. (2010). A meta-analytic review of polyunsaturated fatty acid compositions in patients with depression. Biol. Psychiatry 68 140–147. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Yan Y., Li F., Zhang D. (2016). Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis. Nutrition 32 296–302. 10.1016/j.nut.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. H., Dwyer D. S. (2005). Second-generation antipsychotic drugs, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine enhance neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells via PI3K/AKT, ERK, and pertussis toxin-sensitive pathways. J. Mol. Neurosci. 27 43–64. 10.1385/JMN:27:1:043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukic I., Mitic M., Djordjevic J., Tatalovic N., Bozovic N., Soldatovic I., et al. (2014). Lymphocyte levels of redox-sensitive transcription factors and antioxidative enzymes as indicators of pro-oxidative state in depressive patients. Neuropsychology 70 1–9. 10.1159/000362841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch R., Diggins E. L., Connors S. L., Zimmerman A. W., Singh K., Liu H., et al. (2017). Sulforaphane from broccoli reduces symptoms of autism: a follow-up case series from a randomized double-blind study. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 6:21644957X17735826. 10.1177/2164957X17735826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. (2013). Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 53 401–426. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-de-Saavedra M. D., Budni J., Cunha M. P., Gómez-Rangel V., Lorrio S., Del Barrio L., et al. (2013). Nrf2 participates in depressive disorders through an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 2010–2022. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Hernández D., Caso J. R., Javier Meana J., Callado L. F., Madrigal J. L. M., García-Bueno B., et al. (2018). Intracellular inflammatory and antioxidant pathways in postmortem frontal cortex of subjects with major depression: effect of antidepressants. J. Neuroinflammation 15:251. 10.1186/s12974-018-1294-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec J. M., Christie J. D., Reddy S. P., Jedlicka A. E., Vuong H., Lanken P. N., et al. (2007). Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J. 21 2237–2246. 10.1096/fj.06-7759com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura A., Ishima T., Fujita Y., Iwayama Y., Hasegawa S., Kawahara-Miki R., et al. (2018). Dietary glucoraphanin prevents the onset of psychosis in the adult offspring after maternal immune activation. Sci. Rep. 8:2158. 10.1038/s41598-018-20538-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullumsmith R. E., Hammond J. H., Shan D., Meador-Woodruff J. H. (2013). Postmortem brain: an underutilized substrate for studying severe mental illness. Neuropsychopharmacology 39 65–87. 10.1038/npp.2013.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechawar N., Savitz J. (2016). Neuropathology of mood disorders: do we see the stigmata of inflammation? Transl. Psychiatry 6:e946. 10.1038/tp.2016.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello A. H., Gassenferth A., Souza L. R., Fortunato J. J., Rezin G. T. (2014). ω-3 and major depression: a review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 26 178–185. 10.1017/neu.2013.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon S. H., Wolkowitz O. M., Schonemann M. D., Epel E. S., Rosser R., Burke H. B., et al. (2016). Alterations in leukocyte transcriptional control pathway activity associated with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatment. Transl. Psychiatry 6:e821. 10.1038/tp.2016.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-David I., Tritschler L., Ali Z. E., Damiens M. H., Pallardy M., David D. J., et al. (2015). Nrf2-signaling and BDNF: a new target for the antidepressant-like activity of chronic fluoxetine treatment in a mouse model of anxiety/depression. Neurosci. Lett. 597 121–126. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Haroon E., Felger J. C. (2017). Therapeutic implications of brain-immune interactions: treatment in translation. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 334–359. 10.1038/npp.2016.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Maletic V., Raison C. L. (2009). Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 65 732–741. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. H., Raison C. L. (2016). The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16 22–34. 10.1038/nri.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E. A., Ogrodnik M. A., Plave A., Mao-Draayer Y. (2018). Emerging understanding of the mechanism of action for dimethyl fumarate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 9:5. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K., Sasaki S. (2010). Dietary intake and depressive symptoms: a systemic review of observational studies. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res. 54 471–488. 10.1002/mnfr.200900157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler E. J., Barrot M., DiLeone R. J., Eisch A. J., Gold S. J., Monteggia L. M. (2002). Neurobiology of depression. Neuron 34 13–25. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00653-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler E. J., Hyman S. E. (2010). Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 1161–1169. 10.1038/nn.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell M. A., Hayes J. D. (2015). The Keap1/Nrf2 pathway in health and disease: from the bench to the clinic. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43 687–689. 10.1042/BST20150069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J. C., Lawson M. A., André C., Moreau M., Lestage J., Castanon N., et al. (2009). Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol. Psychiatry 14 511–522. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor R. M., Cryan J. F. (2014). Adolescent brain vulnerability and psychopathology through the generations: role of diet and dopamine. Biol. Psychiatry 75 4–6. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgi Y., Futamura T., Kikuchi T., Hashimoto K. (2013). Effects of antidepressants on alternations in serum cytokines and depressive-like behavior in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 103 853–859. 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie A., O’Neil R. S., Itsiopoulos C., Jacka F. N. (2015). The impact of whole-of-diet interventions on depression and anxiety: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Public Health Nutr. 18 2074–2093. 10.1017/S1368980014002614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T., Keshavan M., Giedd J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 947–957. 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergola P. E., Raskin P., Toto R. D., Meyer C. J., Huff J. W., Grossman E. B., et al. (2011). Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N. Eng. J. Med. 365 327–336. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raison C. L., Lowry C. A., Rook G. A. (2010). Inflammation, sanitation, and consternation: loss of contact with coevolved, tolerogenic microorganisms and the pathophysiology and treatment of major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67 1211–1224. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D., Villeneuve N. F., Jiang T., Wu T., Lau A., Toppin H. A., et al. (2011). Brusatol enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated defense mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 1433–1438. 10.1073/pnas.1014275108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghafian F., Malmir H., Saneei P., Milajerdi A., Larijani B., Esmaillzadeh A. (2018). Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of depression: accumulative evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Br. J. Nutr. 119 1087–1101. 10.1017/S0007114518000697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris J., Logan A. C., Akbaraly T. N., Amminger G. P., Balanzá-Martínez V., Freeman M. P., et al. (2015). Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry 2 271–274. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00051-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak T. W., Nucifora L. G., Koga M., Shaffer L. S., Higgs C., Tanaka T., et al. (2018). Sulforaphane augments glutathione and influences brain metabolites in human subjects: a clinical pilot study. Mol. Neuropsychiatry 3 314–222. 10.1159/000487639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton R. C., Claiborne J., Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M., Reddy R., Aschner M., Lewis D. A., et al. (2011). Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 16 751–762. 10.1038/mp.2010.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiina A., Kanahara N., Sasaki H., Oda Y., Hashimoto T., Hasegawa T., et al. (2015). An open study of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extract in patients with schizophrenia. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 13 62–67. 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.1.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai Y., Fujita Y., Hashimoto R., Ohi K., Yamamori H., Yasuda Y., et al. (2015). Dietary intake of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extracts during juvenile and adolescence can prevent phencyclidine-induced cognitive deficits at adulthood. PLoS One 10:e0127244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Venkannagari S., Oh K. H., Zhang Y. Q., Rohde J. M., Liu L., et al. (2016). Small molecule inhibitor of NRF2 selectively intervenes therapeutic resistance in KEAP1-deficient NSCLC tumors. ACS Chem. Biol. 11 3214–3225. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Connors S. L., Macklin E. A., Smith K. D., Fahey J. W., Talalay P., et al. (2014). Sulforaphane treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 15550–15555. 10.1073/pnas.1416940111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. (2013a). Toward clinical application of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 340–346. 10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Shibata T., Takaya K., Shiraishi K., Kohno T., Kunitoh H., et al. (2013b). Regulatory nexus of synthesis and degradation deciphers cellular Nrf2 expression levels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33 2402–2412. 10.1128/MCB.00065-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Yamamoto M. (2015). Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88 93–100. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K., Tsujita T., Hayashi M., Ojima A., Keleku-Lukwete N., Katsuoka F., et al. (2017). Halofuginone enhances the chemo-sensitivity of cancer cells by suppressing NRF2 accumulation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 103 236–247. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao F., Wang X., Niu Y., Niu L., Wang C. (2018). Recent advances in nutrition for the treatment of depressive disorder. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10.2174/1381612824666180803113106 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y., Yang Y. X., Zhe H., He Z. X., Zhou S. F. (2014). Bardoxolone methyl (CDDO-Me) as a therapeutic agent: an update on its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 8 2075–2088. 10.2147/DDDT.S68872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardyn J. D., Ponsford A. H., Sanderson C. M. (2015). Dissecting molecular cross-talk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43 621–626. 10.1042/BST20150014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B., Dwyer D. S. (2009). Structure-based discovery of low molecular weight compounds that stimulate neurite outgrowth and substitute for nerve growth factor. J. Neurochem. 110 1876–1884. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2017). Depression. Available at: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Kensler T. W., Motohashi H. (2018). The KEAP1-NRF2 system: a thiol-based sensor-effector apparatus for maintaining redox homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 98 1169–1203. 10.1152/physrev.00023.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Kyo M., Kamiya T., Tanaka T., Engel J. D., Motohashi H., et al. (2006). Predictive base substitution rules that determine the binding and transcriptional specificity of Maf recognition elements. Genes Cells 11 575–591. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Ren Q., Zhang J. C., Chen Q. X., Hashimoto K. (2017). Altered expression of BDNF, BDNF pro-peptide and their precursor proBDNF in brain and liver tissues from psychiatric disorders: rethinking the brain-liver axis. Transl. Psychiatry 7:e1128. 10.1038/tp.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Yang C., Ren Q., Zhang J. C., Chen Q. X., Shirayama Y., et al. (2016). Regional differences in the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) pro-peptide, proBDNF and preproBDNF in the brain confer stress resilience. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 266 765–769. 10.1007/s00406-016-0693-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Cheng Y., Zhao J., Rong J. (2015c). Releasing Nrf2 to promote neurite outgrowth. Neural. Regen. Res. 10 1934–1935. 10.4103/1673-5374.169618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Shirayama Y., Zhang J. C., Ren Q., Hashimoto K. (2015a). Peripheral interleukin-6 promotes resilience versus susceptibility to inescapable stress. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 27 312–316. 10.1017/neu.2015.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Shirayama Y., Zhang J. C., Ren Q., Hashimoto K. (2015b). Regional differences in brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels and dendritic spine density confer resilience to inescapable stress. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18:yu121. 10.1093/ijnp/pyu121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Yang M., Dang R., Xu P., Guo Y., Han W., Liao D., et al. (2018). Dl-3-n-Butylphthalide improves lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior in rats: involvement of Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways. Psychopharmacology 235 2573–2585. 10.1007/s00213-018-4949-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W., Zhang J. C., Dong C., Zhuang C., Hirota S., Inanaga K., et al. (2015). Effects of amycenone on serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-10, and depression-like behavior in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 136 7–12. 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W., Zhang J. W., Ishima T., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., et al. (2016a). Antidepressant effects of TBE-31 and MCE-1, the novel Nrf2 activators, in an inflammation model of depression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 793 21–27. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W., Zhang J. W., Ishima T., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., et al. (2016b). Role of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in depression and dietary intake of glucoraphanin confers stress resilience in mice. Sci. Rep. 6:30659. 10.1038/srep30659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. J., Bruno D., Pomara N. (2014). A review of the relationship between pro-inflammatory cytokines and major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 169 15–20. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Pan S., Dong M., Niu Y. (2017). Astragaloside IV attenuates lead acetate-induced inhibition of neurite outgrowth through activation of Akt-dependent Nrf2 pathway in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1863 1195–1203. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Wu J., Fujita Y., Yao W., Ren Q., Yang C., et al. (2014). Antidepressant effects of TrkB ligands on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18:yu077. 10.1093/ijnp/pyu077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Han M., Shirayama Y., Hashimoto K. (2018). Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway confers resilience versus susceptibility to inescapable electric stress. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 10.1007/s00406-017-0848-0 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2017a). Blockade of interleukin-6 receptor in the periphery promotes rapid and sustained antidepressant actions: a possible role of gut-microbiota-brain axis. Transl. Psychiatry 7:e1138. 10.1038/tp.2017.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2015). Comparison of ketamine, 7,8-dihydroxyflavone, and ANA-12 antidepressant effects in the social defeat stress model of depression. Psychopharmacology 232 4325–4335. 10.1007/s00213-015-4062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2017b). Prophylactic effects of sulforaphane on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 39 134–144. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. C., Yao W., Hashimoto K. (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) – TrkB signaling in inflammation-related depression and potential therapeutic targets. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14 721–731. 10.2174/1570159X14666160119094646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Talalay P., Cho C. G., Posner G. H. (1992). A major inducer of anticarcinogenic protective enzymes from broccoli: isolation and elucidation of structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 2399–2403. 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]