Abstract

Introduction

Phaeochromocytomas/paragangliomas (PHAEO/PG) are linked to hereditary syndromes including Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). Current guidelines do not recommend biochemical screening for PHAEO/PG in asymptomatic or normotensive patients with NF-1. This strategy may miss preventable morbidities in those patients who ultimately present with symptomatic PHAEO/PG. Our aim was to review the literature and extract data on mode of presentation and the incidence of reported adverse outcomes.

Methods

PubMed and EMBASE literature search using the keywords ‘Phaeochromocytoma’, ‘Paraganglioma’ and ‘Neurofibromatosis’ was performed looking for reported cases from 2000 to 2018.

Results

Seventy-three reports of NF-1 patients with PHAEO/PG were found. Patients were predominately women (n = 40) with a median age of 46 years (range 16–82). PHAEO/PG was found incidentally in most patients, 36/73 did not present with typical symptoms while 27 patients were normotensive at diagnosis. Thirty-one patients had adverse outcomes including metastases and death.

Conclusion

Given the protean presentation of PHAEO/PG, relying on symptomology and blood pressure status as triggers for screening, is associated with adverse outcomes. Further studies are required to ascertain whether biochemical screening in asymptomatic and normotensive patients with NF-1 can reduce the rate of adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Phaeochromocytoma, paraganglioma, neurofibromatosis-1, screening

Introduction

Phaeochromocytomas/paragangliomas (PHAEO/PG) are chromaffin cell tumours, which can occur sporadically or as part of other hereditary syndromes including multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 (MEN-2), Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome (VHL) and Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). NF-1 is a multi-systemic neuro-cutaneous disorder transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern with complete penetrance and a prevalence of 1 in every 2500–3000 individuals. It is due to a mutation in the NF-1 gene located on chromosome 17 (1). NF-1 can be diagnosed clinically in individuals showing two or more of the clinical criteria (2). The prevalence of PHAEO/PG in patients with NF-1 is thought to be 0.1–5.7% (3). However, in the last few years, some studies reported a higher prevalence rate especially when NF-1 patients are screened prospectively, suggesting that the true prevalence of PHAEO/PG may be underestimated (4, 5). It is recommended to screen for PHAEO/PG in individuals with other predisposing genetic disorders; however, neither adult nor paediatric NF-1 guidelines recommend routine biochemical screening in NF-1 unless patients are hypertensive or symptomatic (6, 7). Patients with undiagnosed PHAEO/PG are at risk of developing life-threatening cardiovascular complications due to phaeochromocytoma crises triggered by tumour manipulation, anaesthesia, drugs, pregnancy (8) or rarely, metastatic disease. Given the uncertainty regarding the value of screening, we reviewed the literature for evidence of potentially preventable complications related to a diagnosis of PHAEO/PG in patients with NF-1.

Methods

We performed a PubMed and EMBASE search with the keywords ‘Phaeochromocytoma’, ‘Paraganglioma’ and ‘Neurofibromatosis’ from 2000 to 2018. Additional reports were also found through Google search. Paediatric, non-human, non-English and duplicate publications were excluded. Any conference paper was included only if sufficient information was available within the abstract. A diagnosis of hypertension was assigned to patients stated to have such a diagnosis or described as being on anti-hypertensive medications. Classical PHAEO symptoms were defined as the presence of any of the followings: headaches, palpitations and sweating (9). We looked into the patients demographics, mode of presentation and the occurrence of death, metastases or any adverse cardiovascular complications attributed to hypertensive crisis or circulating catecholamines.

Results

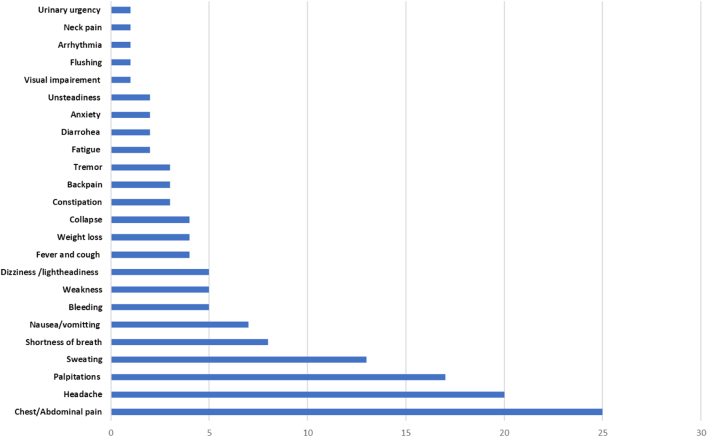

Review of the English literature revealed 73 isolated case reports of PHAEO/PG in the context of NF-1 over the last 18 years (see Supplementary Data). The patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The median age at presentation was 46 years and most patients were females (n = 40). Thirty-six patients did not report any of the typical symptoms and 27 patients were normotensive prior to the diagnosis. The symptoms that led to the diagnosis of PHAEO are summarised in Fig. 1. Data on the mode of presentation were available in 66 patients: 44 patients were diagnosed incidentally, 12 and 10 patients were diagnosed due to the presence of symptoms or persistent hypertension, respectively. No tumour was found by routine biochemical surveillance. The tumour was mostly intra-adrenal and unilateral (59/72) with an average size 5.6 ± 2.89 cm.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 73 patients with PHAEO/PG and NF-1 in the literature.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age in years: Median (range) | 46 (16–82) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 32/72 |

| Female | 40/72 |

| Patients without classical PHAEO/PG symptoms | 36/73 |

| Normotensive patients at diagnosis | 27/73 |

| Mode of presentation | |

| Incidental | 44/66 |

| Symptoms | 12/66 |

| Hypertension | 10/66 |

| Tumour location | |

| Unilateral | 59/72 |

| Bilateral | 12/72 |

| Extra-adrenal | 2/72 |

| Tumour size in cm (mean ± s.d.) | 5.5 ± 2.9 |

Figure 1.

Presenting symptoms which led to the diagnosis of PHAEO/PG in 73 patients with NF-1. Y-axis: reported symptoms, X-axis: number of patients.

Thirty-one patients had major complications including metastases, death and cardiovascular sequelae i.e. acute myocardial infarctions, acute cerebral events, cardiomyopathy and arterial rupture (Table 2). The median age for the cohort of NF-1 with complications was 40 years of age with almost half of patients (15/31) presented before or at the age of 40 years. In patients who had complications, 18/31 did not report any of the typical PHAEO symptoms and 9/31 were normotensive.

Table 2.

Reported adverse outcomes preceded the confirmation of underlying PHAEO/PG in patients with NF-1 from case reports (n = 31).

| Outcome | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Death | 3 |

| Metastatic PHAEO/PG | 7 |

| Hypertensive crisis | 6 |

| Myocardial infarction/myocarditis | 7 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 4 |

| Heart/or multi-organ failure | 6 |

| Stroke | 2 |

| Bleeding/vascular complications | 4 |

| Other* | 2 |

*Includes renal failure from multiple anti-hypertensives in a patient with previous kidney transplant and one patient presented with shock and adrenal gland rupture.

In our literature search, we found seven studies reporting 113 patients of NF-1 and PHAEO/PG in which a significant percentage of patients had atypical presentation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Literature review of published studies reporting cases of NF-1 and PHAEO/PG since 2000 (studies included are those reporting at least five patients of NF-1/PHAEO).

| Author (Ref.) | Type of study | No. of NF-1 and PHAEO/PG | Asymptomatic/non-classical symptoms (%) | No. of normotensive patients | No. of malignant tumours | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amar et al. (20) | Prospective | 13 | – | – | 1 | |

| Bausch et al. (21) | Retrospective | 25 | – | – | 3 | |

| Zinnamosca et al. (4) | Prospective | 7 | 3 | 1 | – | |

| Shinall et al. (22) | Retrospective | 6 | 3 | 5 | ||

| Kepenekian et al. (5) | Prospective | 12 | 10 | 10 | 6 patients had secretory PHAEO. Only two patients were symptomatic and hypertensive | |

| Moramarco et al. (10) | Retrospective | 9 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Gruber et al. (14) | Retrospective | 41 | 3 | 21 patients presented with symptoms including paroxysmal hypertension, headaches, palpitation and hyperhidrosis |

Discussion

PHAEO/PG in patients with a known diagnosis of NF-1 seems to mostly present as an incidental finding in the fourth decade of life. Similar findings were reported in one study (10) which compared the age of presentation in NF-1 to that of other genetic syndromes and found that NF-1 patients are often diagnosed at an older age presumably due to lack of routine screening.

In our literature search, over half of patients with NF-1 and PHAEO/PG were females (40/72). NF-1 women are particularly at increased risk of having maternal and foetal complications during pregnancy/labour if they have undiagnosed PHAEO/PG (11). Intra and post-partum complications including arrhythmia, pulmonary oedema, hypertensive crisis and even death have been reported (12, 13). A recent study found that all cases of bilateral, metastatic and recurrent PHAEO/PG occurred in women (14). This signifies the importance of screening women with NF-1 in pre-conception/antenatal period.

Complications preceded the diagnosis of PHAEO/PG in 31/73 of patients who suffered significant morbidities including metastases and sudden death, which potentially could have been avoided (Table 2). Haemothorax, non-haemorrhagic stroke and myocardial infarction were also reported (15, 16, 17). The median age for patients who developed complications was 40 years (vs 47.5 years for patients who had no complications) with almost half of patients presenting at the age of 40 years or younger (15/31). This observation may be relevant when considering the timing of screening.

In PHAEO, it has been reported that around 5–15% of patients could be normotensive (18) though in our literature search, 27/73 of patients were normotensive and of those, around a third (9/27) suffered adverse events. Such patients would not qualify for screening based on the current NF-1 recommendations (6, 7).

While the classical triad of headache, palpitations and sweats is highly suggestive of PHAEO, the condition is still regarded ‘the great mimic’ as the clinical presentation can be diverse with non-specific signs and symptoms (19). We found that almost half of patients (36/73) did not report any of the classical manifestations but presented with non-specific symptoms (Fig. 1).

We have found seven studies in the literature that reported 113 patients of NF-1 and PHAEO/PG (Table 3) but unfortunately, we could not extract complete clinical information regarding the details of presentation and/or presence of cardiovascular complications for each patient; however, we noticed a significant number of patients who presented in atypical way. This suggests that in addition to blood pressure status, symptomology is not a reliable criterion for selecting NF-1 patients for screening.

Given this protean presentation patients could undergo multiple consultation, irrelevant investigations and unnecessary invasive procedures over years before the diagnosis of PHAEO/PG is arrived at.

Acknowledging the genetic susceptibility and the high pre-test probability of having PHAEO/PG, it can be argued that screening for PHAEO/PG should be considered in every patient with NF-1 and such approach is likely to be cost-effective in terms of preventing morbidity and mortality.

Moreover, screening for PHAEO/PG fulfils the criteria for screening set by the World Health Organization (WHO) (23) as the disease poses an important health problem in this patients’ group while facilities for screening, diagnosis and treatment are now widely available in the developed world. Indeed, patients with NF-1 and PHAEO/PG were found to suffer the worst intra-operative haemodynamic and post-operative outcomes during adrenalectomy due to larger tumour size at eventual diagnosis and higher levels of catecholamines as compared to MEN-2 and VHL (24). This result is likely to be related to the lack of an agreed screening consensus in asymptomatic NF-1 as compared to other syndromes.

The standard method of screening for hereditary PHAEO/PG would be by measurements of supine plasma free metanephrines (or urinary fractionated metanephrines) (25) and if positive, subsequent appropriate radiological imaging should be considered. Contrary to suggestions made by Kepenkian (5) that case detection for PHAEO/PG should be initiated after the age of 40 years, our observation points towards commencing screening earlier. In our literature search, the youngest patient who had metastatic PHAEO was 16 years of age (26), and it would seem reasonable to commence screening few years before this age.

Our review is not without limitations. Authors tend to selectively report cases where a rare combination of PHAEO/PG and other NF-1-associated findings/disorders were discovered and/or or when patients suffered a major complication worth of reporting. Despite those caveats, our findings strongly strengthen the message for screening, raise awareness about the heterogeneity of presentation among those caring for NF-1 and underscore the impact of PHAEO/PG under-recognition. Further prospective studies are needed to ascertain if applying such screening strategy can reduce the rate of complications and improve prognosis in this relatively rare disease but until then, the accumulating evidence in the literature is in favour of routine screening of all NF-1 patients highlighting that revisiting the existing guidelines may be needed.

We recommend that screening for PHAEO/PG should be part of the NF-1 care pathway irrespective of symptoms or blood pressure status. We agree with the recommendations suggested by Gruber et al. (14) that biochemical screening should be offered to all NF-1 patients at an early age (10–14 years) and repeated every 3 years. We believe that such strategy is acceptable given the relatively lower prevalence, penetrance rate and risk of multifocal disease in NF-1 as compared to other hereditary PHAEO/PG syndromes (27, 28) where less screening intervals are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author contribution statement

Al-Sharefi performed the literature search, summarised and analysed the results and wrote the initial paper draft. Perros and James revised the draft several times and supervised the manuscript writing.

References

- 1.Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, Gutmann DH, Korf B, Maria BL. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics 2009. 123 124–133. ( 10.1542/peds.2007-3204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Archives of Neurology 1988. 45 575–578. ( 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520290115023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walther MM, Herring J, Enquist E, Keiser HR, Linehan WM. Von Recklinghausen’s disease and pheochromocytomas. Journal of Urology 1999. 162 1582–1586. ( 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68171-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zinnamosca L, Petramala L, Cotesta D, Marinelli C, Schina M, Cianci R, Giustini S, Sciomer S, Anastasi E, Calvieri S, et al Nurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and pheochromocytoma: prevalence, clinical and cardiovascular aspects. Archives of Dermatological Research 2011. 303 317–325. ( 10.1007/s00403-010-1090-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kepenekian L, Mognetti T, Lifante JC, Giraudet Al, Houzard C, Pinson S, Borson-Chazot F, Combemale P. Interest of systematic screening of pheochromocytoma in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. European Journal of Endocrinology 2016. 175 335–344. ( 10.1530/EJE-16-0233) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hersh JH. & American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children with neurofibromatosis. Pediatrics 2008. 121 633–642. ( 10.1542/peds.2007-3364) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, Moss C, Wilshaw H, Evans DG, Upadhyaya M, Towers R, Gleeson M, Steiger C, et al Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of Medical Genetics 2007. 44 81–88. ( 10.1136/jmg.2006.045906) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitelaw BC, Prague JK, Mustafa OG, Schulte KM, Hopkins PA, Gilbert JA, McGregor AM, Aylwin SJ. Phaeochromocytoma crisis. Clinical Endocrinology 2014. 80 13–22. ( 10.1111/cen.12324) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soltani A, Pourian M, Davani BM. Does this patient have Pheochromocytoma? A systematic review of clinical signs and symptoms. Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders 2016. 15 6 ( 10.1186/s40200-016-0226-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moramarco J, El Ghorayeb N, Dumast N, Nolet S, Boulanger N, Burnichon N, Lacroix A, Elhaffaf Z, Gimenez Roqueplo AP, Hamet P, et al Pheochromocytoma are diagnosed incidentally and at older age in neurofibromatosis type 1. Clinical Endocrinology 2017. 86 332–339. ( 10.1111/cen.13265) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannelli M, Bemporad D. Diagnosis and management of Pheochromocytoma during pregnancy. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2002. 25 567 ( 10.1007/BF03345503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecchi R, Frati P, Capri O, Cipollon L. A rare case of sudden death due to hypotension during cesarean section in a woman suffering from Pheochromocytoma and Neurofibromatosis. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2013. 58 1636–1639. ( 10.1111/1556-4029.12279) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi N, Nishijima K, Orisaka M, Tsuyoshi H, Kurokawa T, Kato K, Shirafuji A, Arakawa K, Hisazaki K, Tada H, et al Amniotic fluid embolism triggered by hypertensive crisis due to undiagnosed pheochromocytoma in a pregnant subject with neurofibromatosis-1. AACE Clinical Case Reports 2015. 1 e178–e181. ( 10.4158/EP14108.CR) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruber L, Erickson N, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Thompson GB, Young WF, Jr, Bancos I. Pheochromocytoma and paranganglioma in Neurofibromatosis type 1. Clinical Endocrinology 2017. 86 141–149. ( 10.1111/cen.13163) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conlon N, Redmond K, Celi L. Spontaneous hemothorax in a patient with Neurofibromatosis type 1 and undiagnosed pheochromocytoma. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2007. 84 1021–1023. ( 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulkina LS, Newton CA, Drake AJ, 3rd, Tanenberg RJ. Acute myocardial infarction attributable to adrenergic crises in a patient with pheochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis 1. Endocrine Practices 2007. 13 269–273. ( 10.4158/EP.13.3.269) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta S, Bhattacherjee S. Type I neurofibromatosis with pheochromocytoma. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health 2013. 2 770–771. ( 10.5455/ijmsph.2013.220420134) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuber S, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinology Metabolism Clinics of North America 2011. 40 295–311. ( 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.02.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen D, Fraker D, Townsend R. Lack of symptoms in patients with histologic evidence of pheochromocytoma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006. 1073 47–51. ( 10.1196/annals.1353.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amar L, Bertherat J, Baudin E, Ajzenberg C, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Chabre O, Chamontin B, Delemer B, Giraud S, Murat A, et al Genetic testing on pheochromocytoma or functional paraganglioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2005. 23 8812–8818. ( 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bausch B, Borozdin W, Hartmut PH. Clinical and genetic characteristic of Neurofibromatosis type 1 and Pheochromocytoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2006. 354 2729–2737. ( 10.1056/NEJMbib66006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinall MC, Solorzano CC. Pheochromocytoma in Neurofibromatosis type 1: when it should be suspected? Endocrine Practices 2014. 20 792–796 ( 10.4158/EP13417.OR) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butz JJ, Yan Q, McKenzie TJ, Weingarten TN, Cavalcante AN, Bancos I, Young WF, Jr, Schroeder DR, Martin DP, Sprung J. Perioperative outcomes of syndromic paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma resection in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, or neurofibromatosis type 1. Surgery 2017. 162 1259–1269. ( 10.1016/j.surg.2017.08.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Grebe SK, Murad MH, Naruse M, Pacak K, Young WF., Jr Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2014. 99 1915–1942. ( 10.1210/jc.2014-1498) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giovannoni I, Callea F, Boldrini R, Inserra A, Cozza R, Francalanci P. Malignant pheochromocytoma in a 16-year-old patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatric and Developmental Pathology 2014. 17 126–129. ( 10.2350/13-10-1397-CR.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welander J, Soderkvist P, Gimm O. Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2011. 18 253–276. ( 10.1530/ERC-11-0170) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aufforth RD, Ramakant P, Sadowski SM, Mehta A, Trebska-McGowan K, Nilubol N, Pacak K, Kebebew E. Pheochromocytoma screening initiation and frequency in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2015. 100 4498–4504. ( 10.1210/jc.2015-3045) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a