Abstract

Background: Malignant mesothelioma (MM) is a rare but deadly malignancy with about 3,000 new cases being diagnosed each year in the US. Very few studies have been performed to analyze factors associated with mesothelioma survival, especially for peritoneal presentation. The overarching aim of this study is to examine survival of the cohort of patients with malignant mesothelioma enrolled in the National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank (NMVB).

Methods: 888 cases of pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma cases were selected from the NMVB database, which houses over 1400 cases that were diagnosed from 1990 to 2017. Kaplan Meier’s method was performed for survival analysis. The association between prognostic factors and survival was estimated using Cox Hazard Regression method and using R software for analysis.

Results: The median overall survival (OS) rate of all MM patients, including pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma cases is 15 months (14 months for pleural and 31 months for peritoneal). Significant prognostic factors associated with improved survival of malignant mesothelioma cases in this NMVB cohort were below the age of 45, female gender, epithelioid histological subtype, stage I, peritoneal occurrence, and had treatment that consisted of combining surgical therapy with chemotherapy. Combined surgical and chemotherapy treatment was associated with improved survival of 23 months in comparison to single line therapies.

Conclusions: There has not been improvement in the overall survival for patients with malignant mesothelioma over many years with current available treatment options. Our findings show that combined surgical and chemotherapy treatment is associated with improved survival compared to local therapy alone.

Keywords: Mesothelioma, Survival analysis. Cox hazard regression analysis, Biobanking, Risk factor

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare and fatal malignancy, associated with occupational and environmental exposure to asbestos. As per American Cancer Society, approximately 3000 new cases are diagnosed per year in the United States. The pleura is the primary site of mesothelioma occurrence, but it also occurs at other sites (pericardium, peritoneum, tunica vaginalis testis) 1, 2. For pleural mesothelioma, the median overall survival age ranges from 21 months (for Stage I) to 12 month (for Stage IV) disease 3. In the 1970s, the incidence of mesothelioma cases started to increase, and it became evident that the occupational and environmental exposures to asbestos (occurring during 1930s–1970s) were associated with the increased incidence of this fatal disease 4. Despite regulations aimed to ban the industrial use of asbestos by US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1970, data do not suggest a decline in the incidence of malignant mesothelioma in the U.S. 5. However, the impact of these changes are difficult to assess due to the fact that mesothelioma is typically diagnosed decades after the initial asbestos exposure 6. A recent multisite cohort investigation reported that the median time of diagnosis from the first environmental exposure was 38.4 years (IQR 31.3–45.4 years) 7.

After the pleura, the peritoneum is the second most frequent site of origin of mesothelioma. The epidemiological studies of peritoneal mesothelioma are complicated by the rarity of this disease, as well as by possible geographic and temporal variations in diagnostic practices 8. While survival for patients with peritoneal mesothelioma is more favorable, with patients surviving up to 60 months 9, 10, limited number of papers explored factors affecting the survival of peritoneal mesothelioma.

However, given the rarity of the disease, few databases have a sufficient number of cases and treatment data to make analysis of therapeutic options with statistical significance possible. NMVB is an especially valuable resource for mesothelioma research, as it includes populations residing in Pennsylvania and New York states (two of the top 5 states for mesothelioma-associated mortality) 11. Previous SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result Program) based studies exploring factors that influence mesothelioma did not include populations residing in Pennsylvania and New York 12.

Previously published research of pleural mesothelioma suggested that histological type (epithelioid) and early stages were associated with improved survival with surgical treatment 13. Other predictive factors explored in previously published literature including gender, advanced age, weight loss, chest pain, poor performance status, as well as low hemoglobin, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis. It has been suggested that female patients with mesothelioma have better life expectancy as compared to male patients 14.

Currently there are few therapeutic options, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and a combination of these options that may significantly improve the overall survival from this deadly disease 15. Considering the aggressive nature and poor prognosis associated with this disease, improving our existing knowledge regarding the biology of the disease and factors predictive of the efficacy of existing therapeutic options and treatment regiments for malignant mesothelioma is critical.

In this study, we analyzed malignant mesothelioma cases from the National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank (NMVB) to evaluate the effect of clinical, pathological, and epidemiological factors, and therapeutic options as determinants of overall survival. Thus our study adds geographic breadth to the existing mesothelioma research knowledge. Additionally, our dataset includes cases of peritoneal mesothelioma, which were not the focus of previous studies.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This study is conducted under the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (IRB #0608194) of NMVB and approval from the principal investigator of NMVB to use the de-identified data from the resource.

Data source

The patient cohort for this study (n=888) is selected from the NMVB resource, which contains both pleural and peritoneal malignant mesothelioma cases. The NMVB database only records general treatment type including cancer directed surgery alone, surgery combined with chemotherapy, as well as surgery combined with chemotherapy and radiation. The specific type of treatment (such as exact surgery type of type of chemotherapy regimen used) is not recorded in the NMVB. NMVB enrolls patients from NMVB collaborative sites (New York University, University of Pennsylvania, University of Maryland, Roswell Park Cancer Institute and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center) in the north east region of country. Thus, there may be a selection bias with patients because there are few patients enrolled from the other regions of the country due to NMVB network coverage. In addition, NMVB has developed to collect mesothelioma biospecimens and data from prospectively consented retrospectively identified patients.

Patient selection

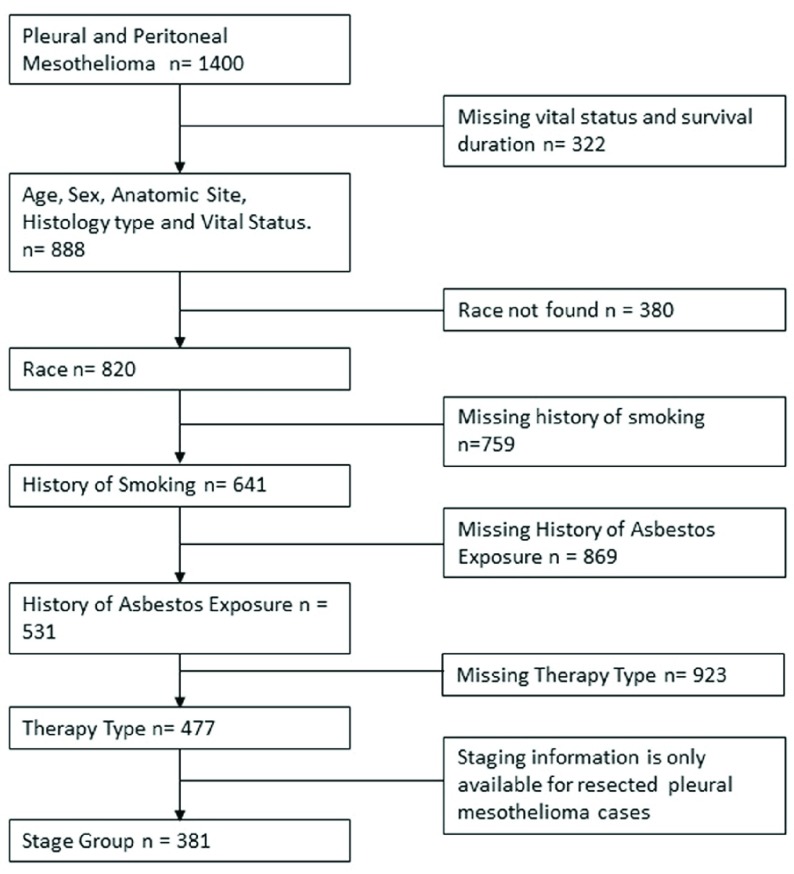

Demographic, treatment, clinical and survival information of histologically confirmed pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma patients diagnosed between 1999 and 2017 were obtained from the NMVB database. Inclusion criteria included the following: confirmed diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma (limited to pleural and peritoneal presentation), presence of complete data on age, gender, race, asbestos exposure, smoking history, history of alcohol use, histological type, site of tumor, disease stage (for pleural presentation), vital status, and survival period. Exclusion criteria included the following: benign mesothelioma, and tumor site other than pleura and peritoneum. This investigation was limited to the most common histological subtypes of malignant mesothelioma including biphasic, epithelial or epithelioid, and sarcomatoid. The desmoplastic histology subtype is classified as sarcomatoid, and papillary mesothelioma as epithelial or epithelioid 16, 17. For the purpose of this study, the tumor anatomic site is classified into two main categories: pleura (which includes visceral/parietal pleura and lung, chest wall, ribs) and peritoneum (includes peritoneal cavity and organs involved). This analysis focused on 888 participants that met the inclusion criteria. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Case selection flow is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Variables | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age | 888 |

| 18–44 | 49 |

| 45–54 | 102 |

| 55–64 | 266 |

| 65–74 | 312 |

| 75 + | 161 |

| Gender | 888 |

| Male | 683 |

| Female | 205 |

| Anatomic Site | 888 |

| Pleural | 740 |

| Peritoneum | 148 |

| Histology | 888 |

| Epithelial or epithelioid | 636 |

| Biphasic | 165 |

| Sarcomatoid | 87 |

| Race | 820 |

| European American | 792 |

| Non-European American | 28 |

| History of Smoking | 641 |

| Yes | 364 |

| No | 277 |

| History of Asbestos Exposure | 531 |

| Yes | 413 |

| No | 118 |

| Stage Group (limited to pleural cases) | 381 |

| I | 178 |

| II | 24 |

| III | 157 |

| IV | 22 |

| Therapy Type | 477 |

| Surgery | 101 |

| Surgery + Chemo | 327 |

| Surgery + Chemo + Radiation | 49 |

Figure 1. Study workflow and case inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Definition of staging and metastatic disease

We have performed analysis of staging data to pleural mesothelioma cases that have surgical resections, there is no formal TNM staging system for peritoneal malignant mesothelioma. We converted the TNM staging of pleural mesothelioma into stage grouping as per College of American Pathology (CAP) protocol 2017 for pleural malignant mesothelioma. The metastatic disease status was defined as the tumor spread from the point of origin to the lymph node and other organs in the body.

Statistical analyses

We included the following variables in the analysis: age, gender, race, smoking history, history of alcohol, asbestos exposure, site of tumor, histological type, treatment, staging and outcome variables including vital status and survival period. Duration of observation was defined as time (in months) between date of initial diagnosis until death (vital status = expired) or the date of last known contact for each participant. Smoking history was analyzed as a dichotomous variable (yes/no), where current, past and smoking for a brief period of time, were grouped as positive history of smoking (yes). The contribution of the three treatment types on mesothelioma survival rate is evaluated in this study.

We constructed survival curves using the Kaplan-Meier method for the entire dataset, followed by a separate analysis limited to female patients. We also performed a separate Kaplan-Meier analysis for peritoneal cases only. We performed Log-rank test of equality across strata for categorical variables. We analyzed the independent contribution to mesothelioma survival of several prognostic with univariable and multivariable regression methods based on the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables were entered into the model using a forward selection approach, starting with the most significant variable (based on the unadjusted p-value) and then continuing in order of significance. We analyzed factors contributing to mesothelioma survival separately for cases with complete data and with missing data to rule out any systematic bias associated with cases with missing data. Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. We used The R Project (version 3.4.0) for Statistical Computing to perform all analysis 18.

Results

The majority of patients were European American (97%) and male (77%). Positive history of smoking has been reported by 364 (57 %) patients among n=641 and positive history of asbestos exposure has been reported by 413 cases (78 %) among n= 531. The epithelial or epithelioid histological subtype was the most prevalent histology in this dataset (n = 636), in 71.4% of cases. Cancer directed surgery has been performed in 54 % cases, while surgery and chemotherapy treatment jointly has been administered in 37% of cases. The median overall survival of the cohort was 15 months. Table 2 and Figure 3 demonstrate the results of the univariable and multivariable analysis respectively (Cox proportional hazard regression models).

Table 2. Unadjusted Cox Hazard Regression Analysis, predictors of mesothelioma survival (n=888). Ref – Reference group.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval

p value for trend |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–44 | 1.00 | Ref |

| 45–54 | 2.0 | 1.3-3 P=0.001 |

| 55–64 | 2.3 | 1.6-3.3 P<0.001 |

| 65–74 | 2.7 | 1.8-3.9 P<0.001 |

| 75+ | 3.4 | 2.3-5.1 P<0.001 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.0 | Ref |

| Male | 1.6 | 1.4.0-1.9 P<0.001 |

| Anatomic site | ||

| Peritoneum | 1.0 | Ref |

| Pleural | 2.1 | 1.7-2.6 P<0.001 |

| Therapy | ||

| Surgery | 1.0 | Ref |

| Surgery, chemo | 0.49 | 0.39-0.62 P<0.001 |

| Surgery, chemo, radiation | 0.63 | 0.44-0.90 P=0.011 |

| Smoking history | ||

| No | 1.0 | Ref |

| Yes | 1.2 | 1-1.5 P=0.022 |

| Stage (pleural cases only) | ||

| I | 1.0 | Ref |

| II | 1.3 | 0.82-2.0 P<0.27 |

| III | 1.7 | 1.31-2.1 P<0.001 |

| IV | 2.0 | 1.24-3.2 P=0.004 |

| Histology | ||

| Biphasic | 1.0 | Ref |

| Epithelial or epithelioid | 0.48 | 0.40-0.57 P<0.001 |

| Sarcomatoid | 0.97 | 0.74-1.26 P=0.797 |

| Race | ||

| Non European American | 1.0 | Ref |

| European American | 1.8 | 1.1-2.8 P<0.012 |

| Asbestos Exposure | ||

| Yes | 1.0 | Ref |

| No | 0.61 | 0.48-0.78 P<0.001 |

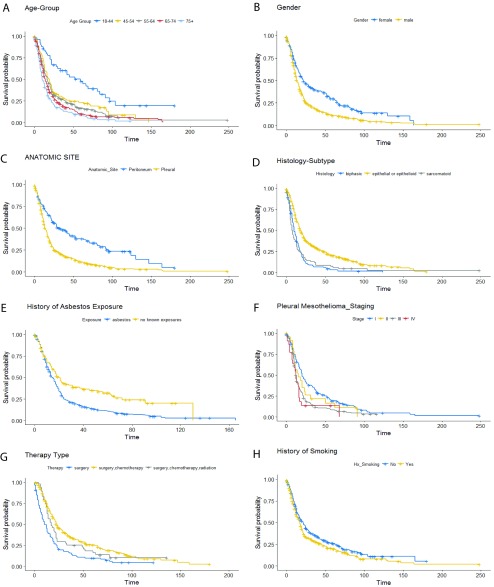

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier Curve analysis performed at age ( a), gender ( b), anatomic site ( c), histology subtype ( d), history of asbestoses exposure ( e), staging (pleural mesothelioma) ( f), therapy type ( g), and history of smoking ( h).

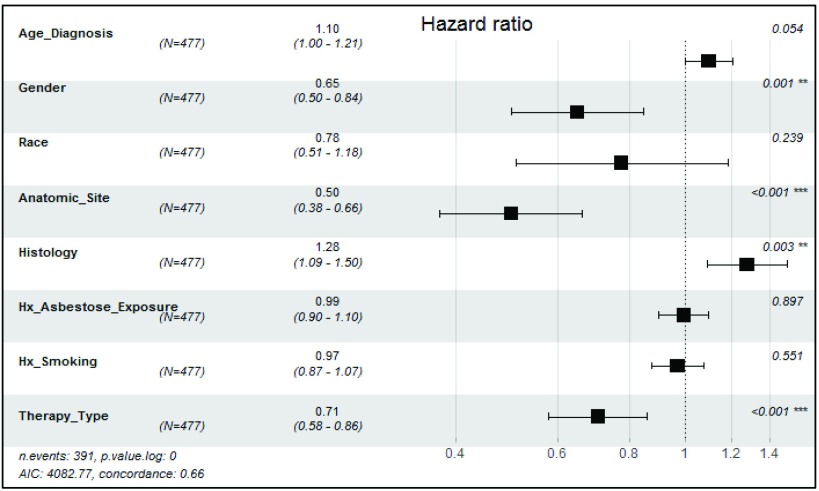

Figure 3. Adjusted Cox Hazard analysis, predictors of mesothelioma survival, multivariable analysis (n=477).

Overall, the non-parametric univariate Kaplan Meier analysis and log rank tests demonstrated longer survival in younger age group (18–44 years), female gender, with no known asbestos exposure history, epithelioid histological type, combined surgical and chemotherapy, Stage I, or peritoneum presentation ( Figure 2a–2i).

The median survival for age group 18–44 years was 59 months (95% CI: 34 - 91) but much less favorable for the age group 75 and over, at 10 months (95% CI: 9 – 13). The median survival for females was 22 months (95% CI: 18 - 30) as compared to 14 months for males (95% CI: 13-16). The group with no reported history of asbestos exposure had a median survival rate of 20 months (95% CI: 16 - 31), as compared to median survival of 15 months (95% CI: 13-17) for the group with reported exposure. The epithelioid histological type median had a median survival of 18 months (95% CI: 17-21) as compared to 10 months for biphasic (95% CI: 9-13) and 7 months for sarcomatoid subtype (95%CI: 6-11). The European American group had a median survival of 15 months (95% CI: 13 – 16) as compare to median survival of 34 months (95% CI: 21-83) in non-European American population. The analysis suggests patients receiving combined therapies [(surgical and chemotherapy (95% CI: 13-19), surgical plus chemotherapy and radiation therapy (95% CI: 10-21)] had a more favorable median survival period in comparison to those with single line surgical therapy (95% CI: 8-14). Overall, median OS was most favorable (23 months (95% CI 21 to 27 months)) for patients treated with combined surgery and chemotherapy. Adding radiation to chemotherapy did not improve survival.

The median survival period for stage I group (including stages IA and IB) was 20 months (95% CI: 18 – 25) as compared to 12 months for stages III and IV. Presentation in the peritoneum site and no history of smoking was also associated with improved survival ( Figure 1). When stratified by anatomic site of tumor, the median survival period among patients with peritoneal mesothelioma, who received surgical and chemotherapy, demonstrated longer survival of 28 months (95% CI: 28 – 45) as compared to 14 months (95% CI: 11 – 17) in patients with pleural mesothelioma.

. Overall, multivariable analysis confirmed that younger age groups, female gender, peritoneal anatomic site, combination of surgery and chemotherapy, no history of smoking, early stage (I and II), and epithelial histology were all predictors of more favorable survival ( Table 2).

In addition, we performed multivariable cox hazard proportional analysis on the complete dataset of n= 477 which had no missing record variables that has obtained from the primary dataset (n= 88). We included all the predictive prognostic variables except for stage, because there is no established TNM staging for peritoneal mesothelioma. We presented these results as supplementary analysis in Figure 3.

Discussion and conclusion

The focus of this study has been on the exploration of risk factors affecting mortality in the states of Pennsylvania and New York, a region with an aging population, environmental concerns, history of notable asbestos exposure, and other risk factors associated with mesothelioma development. This region has not been covered by previously reported investigations. In addition to expanding the geographic region in this study, another added value of this study is that we explored factors contributing to survival for peritoneal mesothelioma separately from the more prevalent pleural presentation. Survival analysis on the NMVB cohort demonstrated that being aged 44 and under, female gender, epithelioid histological subtype, Stage I of the disease, peritoneum anatomic site and surgical therapy combined with chemotherapy were favorable prognostic factors. This study corroborates the analysis of the SEER data by Taioli et al. suggesting that female gender, younger age, early stage, and surgery alone were all prognostic factors 12. This study also corroborates previous investigations suggesting that peritoneal presentation, especially among women, is associated with longer survival 19.

Consistent with the literature, our data suggests that women have longer survival in comparison to men, which may be due to factors like lower levels of smoking amongst females and/or different levels of environmental exposures 14, 20– 23. Specifically, women may be more likely to have para-occupational exposures, which typically refer to an asbestos-exposed worker serving as a vector for the transport of fibers to the household setting and family members. Other terms used in this context include household contact, take-home exposure or domestic exposure 24. Exact factors explaining survival advantage among women needs to be further investigated in future research.

Strengths of this study include the use of a very large dataset collected utilizing uniform data collection protocol. The weaknesses of this study include missing information on specific surgical treatment type in this dataset. Additionally, while we attempted to obtain detailed occupational exposure data for asbestos and other substances, participants’ ability to recall the duration and details of their exposure is a potential source of bias.

Malignant mesothelioma is a life-threatening condition that has been under investigated and is important to investigate further, considering that its mortality epidemic has not shown signs of improvement in the past several decades. Further studies are needed to evaluate screening, diagnostic, staging and treatment for various subtypes of mesothelioma.

In the future, it would be particularly interesting to identify and evaluate cases of nonsurgical mesothelioma management because many patients are not good candidates for surgery. An improved understanding of factors associated with mesothelioma morbidity and mortality may help identify high-risk groups with different occupational exposures who should be further evaluated for responsiveness to preventive and innovative management strategies for mesothelioma. The identification of these factors could help patients at risk for therapy failure who may benefit from novel interventions or avoiding treatments that are not effective or with high mortality risk. We hope our report underscored the significant value of NMVB as a national research resource open to all research community and envision that in the future, existing information repositories like NMVB will be harnessed to greater extent to investigate rare diseases like mesothelioma.

Data availability

The investigator can obtain the de-identified data from National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank by submitting the letter of intent (LOI) ( https://mesotissue.org/node/26). The NMVB Research Evaluation Panel (REP) is composed of extramural scientists with varied expertise including laboratory science, lung pathology, mesothelioma, and statistics ( https://mesotissue.org/rep) reviews scientific merit of requests for NMVB specimens/data and makes recommendation to fulfil the request after the approval of data use agreement (DUA).

Funding Statement

This work is funded and supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in association with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Grant [5U24OH009077-11].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 1 approved

References

- 1. Lanphear BP, Buncher CR: Latent period for malignant mesothelioma of occupational origin. J Occup Med. 1992;34(7):718–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Selikoff IJ, Hammond EC, Seidman H: Latency of asbestos disease among insulation workers in the United States and Canada. Cancer. 1980;46(12):2736–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eiseman E, Bloom G, Brower J, et al. : Case studies of existing human tissue repositories: "Best Practice" for a biospecimen resource for the genomic and proteomic era.Santa Monica, CA: RAND;2003. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang H, Testa JR, Carbone M: Mesothelioma epidemiology, carcinogenesis, and pathogenesis. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9(2–3):147–57. 10.1007/s11864-008-0067-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Price B, Ware A: Time trend of mesothelioma incidence in the United States and projection of future cases: an update based on SEER data for 1973 through 2005. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39(7):576–88. 10.1080/10408440903044928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bianchi C, Bianchi T: Global mesothelioma epidemic: Trend and features. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2014;18(2):82–8. 10.4103/0019-5278.146897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reid A, de Klerk NH, Magnani C, et al. : Mesothelioma risk after 40 years since first exposure to asbestos: a pooled analysis. Thorax. 2014;69(9):843–50. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boffetta P: Epidemiology of peritoneal mesothelioma: a review. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(6):985–90. 10.1093/annonc/mdl345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohamed F, Sugarbaker PH: Peritoneal mesothelioma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3(5):375–86. 10.1007/s11864-002-0003-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sebbag G, Yan H, Shmookler BM, et al. : Results of treatment of 33 patients with peritoneal mesothelioma. Br J Surg. 2000;87(11):1587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amin W, Parwani AV, Schmandt L, et al. : National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank: a standard based biospecimen and clinical data resource to enhance translational research. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:236. 10.1186/1471-2407-8-236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taioli E, Wolf AS, Camacho-Rivera M, et al. : Determinants of Survival in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Study of 14,228 Patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meyerhoff RR, Yang CF, Speicher PJ, et al. : Impact of mesothelioma histologic subtype on outcomes in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. J Surg Res. 2015;196(1):23–32. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards JG, Abrams KR, Leverment JN, et al. : Prognostic factors for malignant mesothelioma in 142 patients: validation of CALGB and EORTC prognostic scoring systems. Thorax. 2000;55(9):731–5. 10.1136/thorax.55.9.731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hiddinga BI, Rolfo C, van Meerbeeck JP: Mesothelioma treatment: Are we on target? A review. J Adv Res. 2015;6(3):319–30. 10.1016/j.jare.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Travis WD: Sarcomatoid neoplasms of the lung and pleura. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(11):1645–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Butnor KJ, Sporn TA, Hammar SP, et al. : Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(10):1304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sugarbaker PH, Welch LS, Mohamed F, et al. : A review of peritoneal mesothelioma at the Washington Cancer Institute. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12(3):605–21, xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mirabelli D, Roberti S, Gangemi M, et al. : Survival of peritoneal malignant mesothelioma in Italy: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(1):194–200. 10.1002/ijc.23866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Curran D, Sahmoud T, Therasse P, et al. : Prognostic factors in patients with pleural mesothelioma: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer experience. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):145–52. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flores RM, Zakowski M, Venkatraman E, et al. : Prognostic factors in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma at a large tertiary referral center. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(10):957–65. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815608d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Linton A, Pavlakis N, O'Connell R, et al. : Factors associated with survival in a large series of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma in New South Wales. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(9):1860–9. 10.1038/bjc.2014.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noonan CW: Environmental asbestos exposure and risk of mesothelioma. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(11):234. 10.21037/atm.2017.03.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]