Abstract

Context:

Tobacco and alcohol addiction has emerged as a major public health issue in most of the regions of the world. It has resulted in enormous disability, disease, and death and acquired the dimension of an epidemic. It is estimated that five million preventable deaths occur every year globally, attributable to tobacco use. The number is expected to double by 2020 if death due to tobacco continues to occur at the same rate. Alcohol, on the other hand, contributes to 25% of all deaths in the age group of 20–39 years. The interventions such as supportive pharmacotherapy, nicotine replacement therapy, counseling, behavioral intervention, psychotherapy, and detoxification therapy are being commonly employed in the management of patients with addiction to tobacco and alcohol.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) among tobacco and alcohol addicts before and after psychological intervention in a de-addiction center.

Settings and Design:

This study was a randomized control trial, focusing on psychological interventions practiced in a de-addiction center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Materials and Methods:

The information on KAP related to tobacco and alcohol was collected at baseline from 83 participants. This was compared with the information collected in the postintervention follow-ups from each participant.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Statistical tests for parametric analysis were done using one-way ANOVA with Scheffe's post hoc test, RMANOVA with Mauchly's test for sphericity assumption, and Bonferroni test for comparing the main effects. Nonparametric tests included Pearson's Chi-square test, McNemar's Chi-square test, Spearman's rho, and Kruskal–Wallis test. The statistical significance was fixed at 0.05.

Results:

The mean KAP score for the study population was highest at the first follow-up followed by the second follow-up for both tobacco and alcohol addiction. The least KAP score was observed at the baseline.

Conclusions:

Although a significant improvement in the mean KAP score was observed at the first follow-up, subsequent follow-up revealed a reduction in the overall KAP score in the present study. This could be attributed to the fact that following their discharge from the de-addiction center, most of the participants reverted back to their deleterious habits.

Keywords: Alcoholism, psychological techniques, substance addiction, tobacco

Substance use disorder is a biopsychosocial condition resulting in increased pleasure and reduced anger, tension, depression, and stress. Some of these effects may be pharmacological, but most of the sedating psychological effects, especially among tobacco users, come from their perception of coping with stress successfully while using tobacco.[1] For effective treatment of substance use disorder, a comprehensive management is essential element.

Donovan and Wallace (1986) devised a biopsychosocial model in addictive behaviors which is commonly used for the treatment of substance use disorder. It addresses the issue of substance use disorder from biological, psychological, and social perspectives. The components include:

Biomedical modalities comprise detoxification regimens, anticraving medication, antagonist medication, substitution treatment, and other pharmacological approaches

Psychological treatment modalities range from addiction counseling to psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral treatment modalities, including insight-oriented psychotherapy, behavior therapy, family therapy, and motivational intervention

Sociocultural treatment modalities include the community reinforcement approach, therapeutic communities, vocational rehabilitation, and culturally specific interventions.[2]

The addictive property of the alkaloid “nicotine” found in tobacco is responsible for causing tobacco dependence among its users. In addition to damage to personal health, tobacco use results in severe societal costs such as reduced productivity and health-care burden, environmental damage, and poverty of the families.[3] Heavy consumption of alcohol, particularly in conjunction with tobacco, is an important risk factor for oral cancer. Approximately, 75%–90% of all cases of oral cancer can be attributed to tobacco and alcohol.[4]

Addiction is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “repeated use of a psychoactive substance or substances, to the extent that the user is:

Periodically or chronically intoxicated

Shows a compulsion to take the preferred substance(s)

Has great difficulty in voluntarily ceasing or modifying substance use

Exhibits determination to obtain psychoactive substances by almost any means

Tolerance is prominent and a withdrawal syndrome frequently occurs when substance use is interrupted.[5]”

Schaef proposed a typology to differentially classify various addictive behaviors. The first type, substance addiction, involves direct manipulation of pleasure through the use of products that are ingested into the body, including drug use disorders and food-related disorders. Drugs of misuse often are grouped into categories such as cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and illicit substance use.[6] Both nicotine and alcohol meet the established criteria for a drug that produces addiction, specifically, dependence and withdrawal.

Globally, more than five million of deaths per year are the result of direct tobacco use while more than 600,000 are the result of nonsmokers being exposed to second-hand smoke.[7] Alcohol consumption, on the other hand, is responsible for the death of approximately 3.3 million people every year representing 5.9% of all deaths.[8]

The situation is more alarming in a developing country like India. India is the second largest producer and consumer of tobacco after China. More than one-third of adults use tobacco in India accounting for 275 million. Nearly 30% of cancers in males in India and more than 80% of all oral cancers are related to tobacco use.[9] A study conducted to examine the association between alcohol, alcohol and tobacco, and mortality in Mumbai, India, revealed that compared to those who never drank alcohol, alcohol drinkers had 1.22 times higher risk of mortality, with the highest risk observed for liver disease. Alcohol drinkers had increased risk of mortality for tuberculosis, cerebrovascular disease, and liver disease. Synergistic effect of tobacco and alcohol showed a higher mortality as compared to individual risk.[10]

Substance abuse (alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs) is considered to be a combination of physical, psychological, social, and occupational problems. Interventions for substance abuse in India are largely limited to specialized de-addiction centers and require a multipronged approach for its management. Interventions mainly focus on the management of physical complications resulting from cessation of drug use, addressing broader issues of motivation, lifestyle adjustment, reducing risk behavior, and developing skills to cope with factors that could trigger drug use. They also emphasize to prevent an occasional lapse from becoming a full-blown relapse to regular drug use.[2]

For delivering an effective treatment, a combination of components of psychological treatments and sociocultural treatment is done. Psychosocial interventions encompass behavioral and psychological strategies usually administered in the context of abstinence-based treatments. These strategies are used either alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy and other medical or social interventions. The intensity, frequency, and duration of these interventions depend on factors such as approach and settings (outpatient, inpatient, partial hospitalization or residential-based treatment settings). Furthermore, these interventions may be delivered in individual or group sessions and may also include family members or peer group.[2]

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the impact of psychological interventions among inpatients of a de-addiction center in improving the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of tobacco and alcohol addicts.

Aim and objectives

Aim

The aim of this study is to compare the KAP among tobacco and alcohol addicts before and after psychological intervention in a de-addiction center.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were as follows:

To provide a baseline data regarding KAP related to tobacco habits

To provide a baseline data regarding KAP related to alcohol habits

To compare the effectiveness of various intervention methods by assessing the change in KAP scores related to tobacco and alcohol habits.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Selection of the de-addiction center

The list of all the government and private de-addiction centers operating in Madhya Pradesh was prepared. A total of 15 recognized de-addiction centers were noted, and this was used as a sampling frame to select the de-addiction center. The selection was made on a random basis using lottery method of simple random sampling technique. This enabled us in the selection of de-addiction center at Indore, Madhya Pradesh. Written permission was obtained from the center in-charge at Indore de-addiction center to carry out the study for the duration of 6 months.

Study design and study setting

This study was a randomized control trial, conducted over a period of 6 months from April 2013 to October 2013 in the Indore de-addiction center, Madhya Pradesh. The effectiveness of two psychological intervention techniques (reading–writing therapy vs. games–narrative therapy) using psychological counseling (motivational intervention) alone as a control was assessed in the de-addiction center at Indore. The success rate among all the intervention methods employed in the study was compared at the time of discharge and 1 month following their discharge from the de-addiction center.

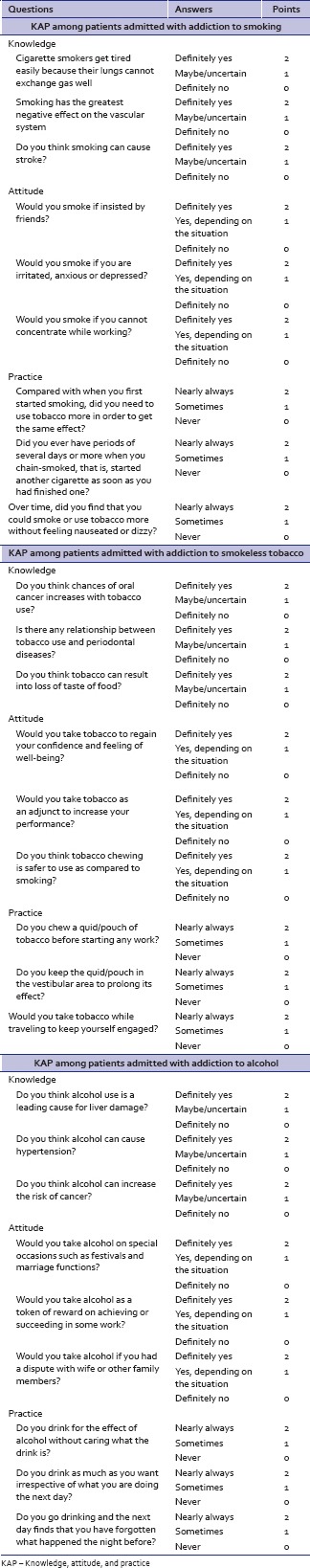

Preparation of the assessment pro forma

An assessment pro forma was designed for collecting the information on demographic details, socioeconomic status (SES), and details of addiction from the study participants. The pro forma included a questionnaire on KAP related to tobacco and alcohol. The information procured using pro forma facilitated the inclusions and exclusions of the study participants. The KAP questionnaire consisted of nine questions (three questions each for KAP, respectively) for smoking, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol addiction [Appendix 1].[11,12]

Pilot testing of the assessment pro forma

The assessment pro forma was pilot tested on ten individuals admitted in the de-addiction to assess its reliability in obtaining the desired information. The pro forma was first filled by the investigator following face-to-face interview with the participants. The interview was repeated by the same investigator after 1 week. The intraclass correlation coefficient value for KAP questionnaire on smoking, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol was 0.980, 0.991, and 0.901, respectively, for single measures. The intraclass correlation coefficient value for KAP questionnaire on smoking, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol was 0.990, 0.996, and 0.948, respectively, for average measures.

Screening of the participants

Short listing of the participants

A list of all the individuals admitted during 1-week period in the de-addiction center was noted from their enrollment registers. Documents and case histories of the patients admitted to these de-addiction centers were thoroughly scrutinized by the investigator to determine their status regarding type of substance abuse. Individuals who were found to be addicted to tobacco and alcohol (alone or in combination with other substance abuse) were selected for face-to-face interview with the investigator.

Face-to-face interview to collect desired information on substance abuse

The short-listed individuals were called for a face-to-face interview with the investigator in the counseling room of the de-addiction center. The interview was carried out to assess their substance abuse in detail using the predesigned and pilot-tested assessment pro forma. It took approximately 10 min to complete collection of data from one participant. The data were collected by a single investigator to avoid any conflict regarding the criteria for making the entry in the assessment pro forma.

At the time of face-to-face interview with the study participants, the informed consent was obtained from the participants after explaining the entire research protocol including the need for such trial, the aims and objectives, the methodology employed in the trial, the duration of trial, the interventions, follow-up, and outcome measures in local language.

Selection of the study participants

The selection of the study participants was made on a weekly basis in the de-addiction center using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

The individuals fulfilling the following criteria were included in the study.

The study participants

Who gave the written informed consent to participate in the study

With addiction to tobacco and alcohol

Having a moderate-to-high level of dependence (dependence score of >5) for smoking/smokeless tobacco/combinations as per Fagerstrom scale

Who agreed to stay as inpatients in the de-addiction centers for the duration of 25–30 days to receive the assigned intervention.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusions were based on the following criteria.

The study participants

With addiction only to alcohol and/or other substances (drug addicts) without addiction to tobacco in any form

Undergoing any other psychopharmacological interventions during the study period

With known drug hypersensitivity, epilepsy, pregnancy, lactation, any serious or unstable cardiac, renal, hepatic, hypertensive, pulmonary, endocrine, or neurological disorder as these participants were not recruited into the de-addiction centers till their condition was medically stable

With either low or very low level of dependence (dependence score of <5) as per Fagerstrom scale

Not willing to stay as inpatients in the de-addiction centers for the duration of 25–30 days to receive the assigned intervention

Individuals failing to offer written informed consent.

Collection of baseline information

The basic demographic information such as patient name, age/sex, address, date of admission, and the telephone number of the family members was collected from each eligible participant. The information on the SES was collected using modified Kuppuswamy scale.[13] The other relevant information such as food habits, type, and duration of substance addiction was also collected. All the participants were then assessed for the presence of conditions such as leukoplakia, erythroplakia, submucous fibrosis, ulcer, or any growth by means of an intraoral examination by a qualified dentist (investigator). The intraoral examination was carried out using mouth mirror and straight probe under natural daylight. The information on the oral conditions was not immediately discussed with the study participant but was noted to facilitate their referral following the completion of the study. At this time, the information on KAP related to tobacco and alcohol was collected from all the eligible participants before group allocation and intervention. All the study participants were given a unique identification number (ID) at this level, and the same ID was used till the completion of the study. The entire data collection was done by a single trained investigator.

Randomization and group allocation

The study participants were allocated into three intervention groups, respectively. The three groups in the de-addiction center were coded as Groups A, B, and C. The randomization and group allocation were done on a quota basis in the de-addiction center by the center in charge. The first five eligible participants admitted to the de-addiction center were allotted to Group A, and then, the next five eligible participants to Group B and Group C, respectively. This group allocation strategy was followed as it was convenient to administer the intervention. The group code was entered on the assessment form of the participant following randomization, and the information on the actual intervention offered to different groups was concealed from the investigator to ensure blinding in the study.

Intervention

The methodology followed at the de-addiction center in Indore was purely based on psychological interventions. The psychological interventions are based on the principle that any type of substance abuse is only due to psychological dependence of an individual toward them, and no drug can substitute the psychological dependence. This can be treated with proper psychological approach alone.

Among the various therapies routinely followed in the center, four most commonly used therapies were clubbed to form two intervention strategies with motivational intervention without these therapies as control.

Thus, the three psychological interventions in the study were as follows:

Group A – Motivational intervention without the therapies assigned in other groups

Group B – Games and story therapy along with motivational intervention

Group C – Reading and writing therapy along with motivational intervention.

Group A – Motivational intervention without the therapies assigned in other groups

All eligible participants allocated to Group A were segregated to a common room. The segregation facilitated easy application of the intervention strategy. These participants were offered motivational intervention along with the participants in other groups. Motivational intervention mainly consisted

Group counseling sessions

Individual counseling sessions

Anonymous meetings.

Group B – Games and story therapy along with motivational intervention

All the eligible participants assigned to Group B were segregated in another room (room no. 2) and were offered motivational intervention as described earlier. Along with motivational intervention, these participants were involved in games and story therapy for a minimum of 2 h in a day.

Games therapy

Games therapy was implemented because games stimulate curiosity and an intellectual thought process. As the participants do not have to face or talk about their personal problems, games therapy does not induce feelings of guilt. Furthermore, games facilitate interactions between players. Games based on cognitive, behavioral, and motivational approaches such as “Pick-Klop” have been effectively implemented in de-addiction.[14] Games therapy was carried out either on individual or group basis under the monitoring of one of the trained counselors. The main aim of this therapy was to divert the participant's attention to some rigorous activity which may mask the craving and withdrawal symptoms. Here, the participant was given short mind games and puzzles that challenged his mental ability. These puzzles and challenges kept the participants mentally engaged and thus distracting them from the craving.

Story therapy

Implication of stories as a therapy had been mentioned in the Professional Practice Guidelines issued by New South Wales (NSW), Department of Health.[15] This therapy emphasizes on highlighting psychological dependence of the addicts through various stories which were related to their personal life. The therapy was undertaken by one of the trained counselors in such a way that each addict correlated the circumstances that led him to addiction, with the content in stories. In each such session, the participants were encouraged to actively participate in the discussions by correlating the various events in the story with their real-life situations.

Group C – Reading and writing therapy along with motivational intervention

All the eligible participants assigned to Group C were segregated in a separate room (room no. 3) and were offered motivational intervention as described earlier. Along with motivational intervention, the participants in this group were offered reading and writing therapy for a minimum of 2 h in a day.

About half the participants in group C were assigned reading therapy and the other half during this time underwent writing therapy. These therapies were offered in such a way that each participant underwent almost equal sessions of reading and writing therapy.

Reading therapy

Reading therapy emphasizes on the use of self-help materials to motivate and guide the process of changing behavior. Self-help materials have been used for the past three decades and studies have supported their effectiveness.[16] This therapy was carried out on group basis. In each session, the participants were given autobiographies of previously admitted patients who had successfully quit their abusive habits. These autobiographies were rotated among the participants in such a way that each participant reads biographies used in the group at least once.

Writing therapy

Expressive writing as a treatment adjunct was assessed by Ames et al., wherein the results suggested the therapy to be effective in smoking cessation treatment.[17] All the participants assigned to writing therapy were given a diary and a pen. These diaries were marked with the identification code of the participant, and they were instructed not to mention their names to ensure anonymity. The principle in writing therapy is that when a person expresses his real-life situations in writing, it will have a deeper impact in molding his attitude and behavior as he will assess each life circumstance thoroughly before writing. This will help the person in realizing the adverse consequence the family and society underwent due to his addiction (repenting his wrongdoings in the past), and at the same time, the benefits that he, his family, and the society may have by his de-addiction.

Follow-up

Two postintervention follow-ups were carried out in the de-addiction center. The first follow-up was done at the time of discharge of the study participants from the center. The second follow-up was done 1 month following the discharge. In each follow-up, the information on KAP related to smoking/smokeless tobacco and alcohol was collected by means of face-to-face interview by the same investigator who recorded baseline information.

Assessment of outcome

The information on KAP related to smoking/smokeless tobacco and alcohol collected at baseline from each participant was compared with the information collected in the postintervention follow-ups. The mean KAP scores between baseline examination and the two follow-up examinations were compared to assess the change in the KAP related to tobacco habits and alcohol.

Debriefing

The study participants and counselors were requested to assemble in a common hall on a fixed day (in the last week of their stay in the center) before their discharge from the center. The cooperation for the research was acknowledged by the investigator. The information related to compliance and adverse events, if any, encountered by the participants during the study period was collected. All other queries by the participants were clarified in this session, and all participants were rewarded with a memento for their cooperation. The information on the various intervention procedures followed in the research was briefly conveyed, and the participants were requested to attend the follow-up at the end of 1 month to know the exact intervention group to which they were assigned.

Data entry and analysis

The data were entered into a personal computer, and statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 20 (IBM, Chicago, USA). The statistical tests used in the present study were grouped into descriptive and inferential statistics.

Descriptive statistics: The quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. The qualitative data were presented as frequencies and percentages

Inferential statistics: The following statistical tests were used to assess the significance of difference with respect to various parameters between different categories and for comparing the difference between baseline and follow-up examinations in each category

Parametric tests: These include one-way ANOVA with Scheffe's post hoc test, RMANOVA with Mauchly's test for sphericity assumption, and Bonferroni test for comparing the main effects

Nonparametric tests: These include Pearson's Chi-square test, Spearman's rho, and Kruskal–Wallis test.

RESULTS

A total of 83 study participants were recruited for the study and were offered psychological interventions. Among the 83 participants, 28 were offered motivational intervention, 28 were offered games and narrative therapy, and the remaining 27 were offered reading and writing therapy.

Gender and age distribution of the study participants in different intervention groups

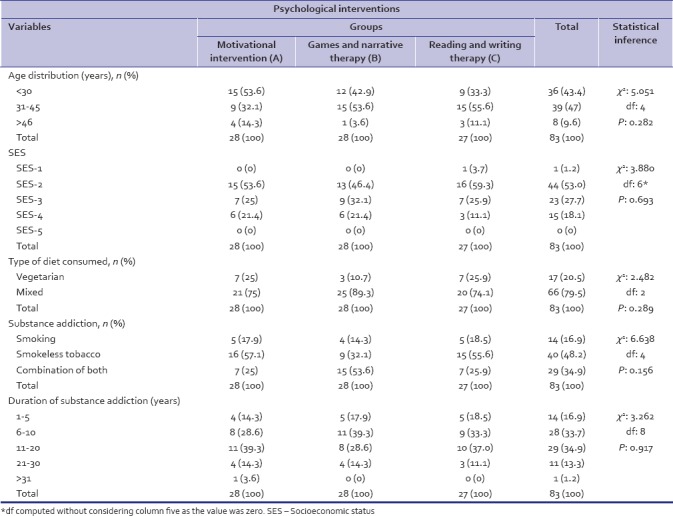

All were males, and the mean age of the study population was 32.3 years with a standard deviation of 9.12. The age range of the study population was 18–65 years. There was no statistically significant difference in the age distribution of the study participants in these three intervention groups [P = 0.282, Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of the study participants in relation to different variables

Distribution of the study participants in relation to socioeconomic status between different intervention groups

Majority of the participants were from upper middle SES group (53%), followed by lower middle (27.7%), upper lower (18.1%), and upper classes (1.2%). None of the participants belonged to lower SES class. The difference in the distribution of study participants in relation to SES between the three intervention groups was not statistically significant [P = 0.693, Table 1].

Distribution of study participants in relation to dietary habits between different intervention groups

There was no statistically significant difference in the dietary habits among the study participants in different intervention groups [P = 0.289, Table 1]. Sixty-six (79.5%) participants were consuming mixed diet (vegetarian as well as nonvegetarian) and 17 (20.5%) were vegetarians.

Distribution of study participants based on type of substance addiction

The participants with addiction to smokeless tobacco (48.2%) and combination of smoking with smokeless tobacco (34.9%) were higher as compared to those with addiction to smoking alone (16.9%). However, on confirming after statistical analysis, this difference seems to be insignificant between the various subgroups undergoing psychological interventions [P = 0.156, Table 1].

Distribution of study participants based on duration of substance addiction

All the study participants were further categorized based on the duration of their substance addiction. Majority of the participants had an addiction of 11–20 years (34.9%), followed by addiction ranging from 6 to 10 years (33.7%). The difference in the distribution of study participants based on the duration of substance addiction was not significant between the three intervention groups [P = 0.917, Table 1].

Knowledge, attitude, and practice related to tobacco habits

Knowledge

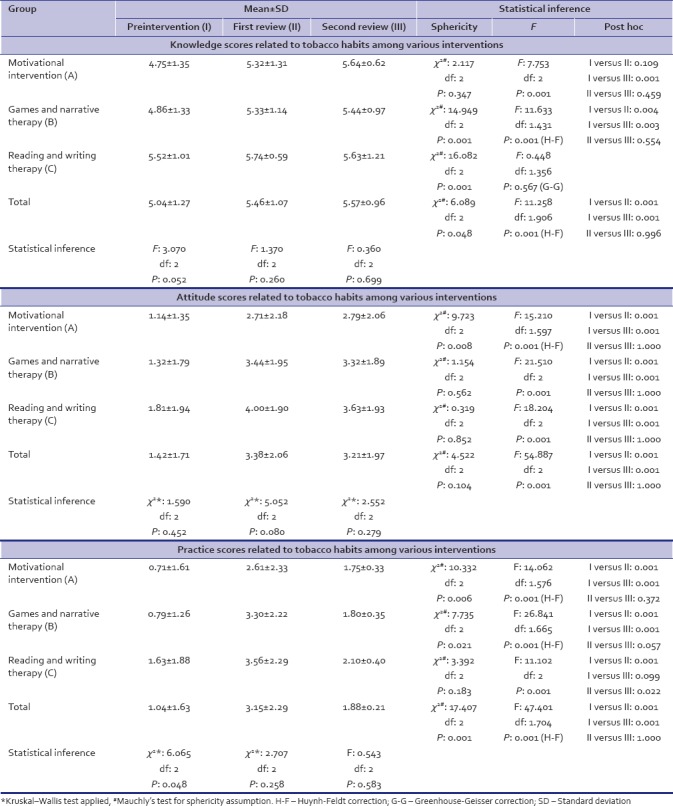

The mean score on the knowledge related to tobacco habits for the study population was 5.04 ± 1.27 at baseline, 5.46 ± 1.07 at the first, and 5.57 ± 0.96 at the second follow-up. The difference in the mean knowledge score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at baseline [P = 0.052, Table 2], first [P = 0.260, Table 2], and second follow-up [P = 0.699, Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of mean knowledge, attitude, and practice scores related to tobacco habits at baseline and postintervention among study participants

The difference in the mean knowledge score between baseline, first, and second follow-up was statistically significant. The mean knowledge score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores [P = 0.001, Table 2]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 2], but the difference between first and second follow-up scores was not statistically significant [P = 0.996, Table 2].

Attitude

The mean score on the attitude related to tobacco habits for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 1.42 ± 1.71, 3.38 ± 2.06, and 3.21 ± 1.97, respectively. The difference in the mean attitude score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at baseline [P = 0.452, Table 2], first [P = 0.080, Table 2], and second follow-up [P = 0.279, Table 2]. At the first follow-up, the mean attitude score was significantly less in the group that received motivational intervention (2.71 ± 2.18). The difference in the mean attitude score on tobacco habits between different intervention groups was significantly lesser [P = 0.080, Table 2] at this follow-up.

The difference in the mean attitude score between baseline, first, and second follow-up was statistically significant. The mean attitude score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores [P = 0.001, Table 2]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 2], but the difference between first and second follow-up scores was not statistically significant [P = 1.000, Table 2]. The most favorable attitude was observed in the first follow-up followed by second follow-up and least favorable attitude at baseline [Table 2].

Practice

The mean score on the practice related to tobacco habits for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 1.04 ± 1.63, 3.15 ± 2.29, and 1.88 ± 0.21, respectively. The difference in the mean practice score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at first [P = 0.258, Table 2] and second follow-up [P = 0.583, Table 2].

The difference in the mean practice score between baseline, first, and second follow-up was statistically significant. The mean practice score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores [P = 0.001, Table 2]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 2].

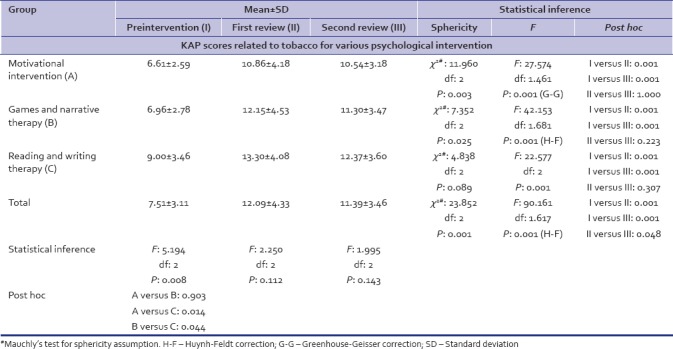

Knowledge, attitude, and practice

The mean KAP score related to tobacco habits for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 7.51 ± 3.11, 12.09 ± 4.33, and 11.39 ± 3.46, respectively. The difference in the mean KAP score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at first [P = 0.112, Table 3] and second follow-up [P = 0.143, Table 3]. At baseline, the mean KAP score was significantly less in the motivational intervention (6.61 ± 2.59) compared to others, and this difference was statistically significant [P = 0.008, Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean KAP score (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice scores combined together) related to tobacco habits at baseline and post-intervention among study participants

The mean KAP score for the study population was highest at the first follow-up (12.09 ± 4.33) followed by second follow-up (11.39 ± 3.46). The difference in the mean KAP score between different intervals was statistically significant [P = 0.001, Table 3]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline against both follow-up examinations [P = 0.001, Table 3] as well as between first and second follow-ups [P = 0.048, Table 3].

Knowledge, attitude, and practice related to alcohol

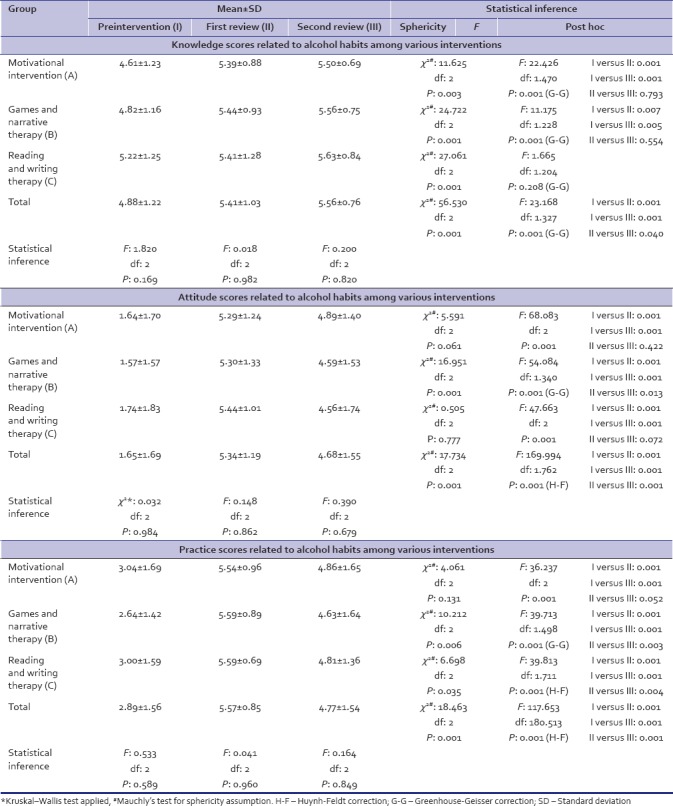

Knowledge

The mean score on the knowledge related to alcohol addiction for the study population was 4.88 ± 1.22 at baseline, 5.41 ± 1.03 at first, and 5.56 ± 0.76 at the second follow-up. The difference in the mean knowledge score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at baseline [P = 0.169, Table 4], first [P = 0.982, Table 4], and second follow-up [P = 0.820, Table 4]. The mean score at baseline was least in the group that received motivational intervention (4.61 ± 1.23).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean knowledge, attitude, and practice scores related to alcohol dependence at baseline and postintervention among study participants

The mean knowledge score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores. The difference in the mean knowledge score between baseline, first, and second follow-up examinations was statistically significant (P = 0.001). The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 4] as well as between first and second follow-ups [P = 0.040, Table 4.]

Attitude

The mean score on the attitude related to alcoholism for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 1.65 ± 1.69, 5.34 ± 1.19, and 4.68 ± 1.55, respectively. The difference in the mean attitude score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant [Table 4].

The difference in the mean attitude score between baseline, first, and second follow-up was statistically significant. The mean attitude score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores [P = 0.001, Table 4]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 4] as well as between first and second follow-up examination [P = 0.001, Table 4]. The most favorable attitude was observed in the first follow-up followed by second follow-up and least favorable attitude at baseline.

Practice

The mean score on the practice related to alcohol addiction for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 2.89 ± 1.56, 5.57 ± 0.85, and 4.77 ± 1.54, respectively. The difference in the mean practice score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at baseline [P = 0.589, Table 4], first [P = 0.960, Table 4], and second follow-up [P = 0.849, Table 4].

The mean practice score increased in the follow-up examinations compared with baseline scores [P = 0.001, Table 4]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline and both the follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 4] as well as between first and second follow-up examination [P = 0.001, Table 4]. The most favorable practice score was observed in the first follow-up followed by second follow-up and least favorable practice score at baseline.

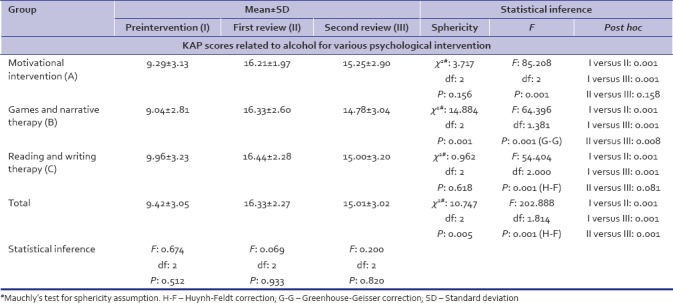

Knowledge, attitude, and practice

The mean KAP score related to alcohol addiction for the study population at baseline, first, and second follow-up was 9.42 ± 3.05, 16.33 ± 2.27, and 15.01 ± 3.02, respectively. The difference in the mean KAP score between different intervention groups was not statistically significant at baseline [P = 0.512, Table 5], first [P = 0.933, Table 5], and second follow-up [P = 0.820, Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparison of mean KAP score (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice scores combined together) related to alcohol dependence at baseline and post-intervention among study participants

The mean KAP score for the study population was highest at the first follow-up (16.33 ± 2.27) followed by second follow-up (15.01 ± 3.02). The difference in the mean KAP score between different intervals was statistically significant [P = 0.001, Table 5]. The post hoc test revealed a significant difference between baseline against both follow-up examinations as well as between first and second follow-ups [P = 0.001, Table 5]. In general, though a significant difference was observed between baseline and other follow-ups, the difference between first and second follow-up examinations was not statistically significant when a separate comparison was made in individual intervention groups [Table 5].

DISCUSSION

Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body. A review of the health effects of tobacco smoking published by the U. S. Surgeon General in 2004 (USDHHS, 2004) expanded the list of diseases known to be caused by smoking to include virtually every organ in the body.[18] Smoking not only affects a person's health but also it affects their material well-being, their personal life, and the health of people around them. Smoking can also contribute to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.[19] Smoking can create a tremendous financial burden for smokers and their families. Smoking a pack of cigarettes a day costs about $100 a week or $5200 a year.[20] Smokeless tobacco, on the other hand, is equally harmful and its continuous use might also cause problems beyond the mouth such as pancreatic cancer, heart disease, and stroke.[21]

Alcohol addiction affects almost every organ in the body and has been associated to cause >60 medical conditions. Alcoholism is a major factor in causation of chronic diseases such as cirrhosis, heart disease, and cancer. It also increases the risk of mortality from acute causes such as traffic accidents and injuries. According to the WHO, alcohol is estimated to be the cause of 3.8% of deaths worldwide, and 4.5% of the total disability-adjusted life years.[10]

Addiction to any substance may be physical and psychological. A person with an addiction for tobacco often finds it difficult to quit these habits owing to the various withdrawal symptoms such as dizziness, depression, feelings of frustration, anxiety, irritability, restlessness, dry mouth, chest tightness, and slower heart rate. These symptoms can make the smoker start smoking again to boost blood levels of nicotine until the symptoms go away.[22] The same holds true for alcohol addiction as well. At this juncture, the de-addiction centers play a vital role in facilitating an addict with supportive interventions which will enable them to overcome their withdrawal symptoms. The de-addiction centers follow a variety of psychological, pharmacological, and combination of other methods to help the addicts overcome their addiction. The present study was undertaken to assess the efficacy of three psychological interventions followed in the de-addiction center in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India.

In our study, the subjective evaluation involved collection of the desired information on the KAP regarding tobacco and alcohol addiction by means of face-to-face interview with the study participants.

There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of study participants with respect to age, gender, SES, and diet at baseline between the different intervention groups. The lack of difference with respect to these parameters ensured uniformity in the distribution of study participants between the various groups before the intervention.

In our study, there was a significant increase in the mean knowledge score in the postintervention follow-ups compared to baseline values. Similar results were obtained in a study conducted by Anjum et al. in which the impact of educational intervention on KAP with regard to water pipe smoking was assessed among adolescents (14–19 years) in Karachi. They surveyed a total of 646 students for the pretest and 250 students for the posttest using a pretested self-administered questionnaire for data collection. The results of their study concluded that the knowledge of the participating students regarding water pipe smoking improved significantly after the health awareness sessions, especially in terms of health hazards associated with water pipe, which was comparable with the present study.[23]

The increase in KAP score postintervention compared to baseline as observed in this study was in agreement with the study by Molina et al. (2012) in which the effectiveness of a tobacco control course was evaluated on the improvement of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about smoking among health science students. Their study included a total of 290 students on the intervention and 256 on the control campus. The intervention consisted of a course on the prevention and control of tobacco use offered only on the intervention campus. Data were collected before the intervention and 6 months afterward. After the course, significant differences between groups were observed and had a positive impact on the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about tobacco of students.[24]

Barbadoro et al. conducted a study among 76 alcohol-addicted persons involved in a residential rehabilitation program in Italy. They administered a questionnaire to obtain information on SES and to assess the short-term effectiveness of the intervention. Long-term effectiveness was assessed by a follow-up interview at 1 year from the intervention. Results showed an improvement of 25.0% in exact answers in relation to the questionnaire. At 1 year from the intervention, the 42 participants who reached follow-up showed a great improvement in knowledge and attitude toward their health.[25] Our study followed the same protocol and incorporated the SES to assess any significant association with SES. Furthermore, similar to their study, our study also found a significant improvement in overall KAP among alcohol-addicted persons involved in a residential rehabilitation program.

The regular counseling sessions, the conducive environment, and interaction with like-minded participants who are willing to quit the habit while in de-addiction center might be the possible explanations for an improvement in KAP scores among our participants. These results were in agreement with the study by Salaudeen et al. who in their study found the health education intervention to significantly increase the level of awareness on the adverse effects of smoking and changing the attitudes among the participants in a favorable direction.[26]

Limitations of the current study

The second follow-up following intervention in the present study was carried out 1 month following the discharge from the de-addiction centers owing to the time constraints and other logistic problems while a follow-up for 6 months–1 year would have been ideal. Furthermore, the study assessed only the dependence status with respect to alcohol and tobacco, ignoring the other substance abuse among the participants such as addiction to brown sugar and ganjha.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

In our study, the mean knowledge score significantly increased in the postintervention follow-ups compared to baseline values. The attitude and practice score related to tobacco and alcohol habits was most favorable in the first follow-up followed by second follow-up. The least favorable attitude and practice score was observed at baseline. The overall KAP score for tobacco and alcohol increased in the postintervention periods compared to baseline values.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I offer my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Resp. Dr. Chandrashekar BR, who has supported me throughout my work with his patience and knowledge. The good advice and support of Dr. Pallavi Singh has been invaluable on both an academic and a personal level, for which I am extremely grateful. I am also thankful to Dr. Ruchika Gupta, Dr. Poonam Tomar Rana, and Dr. Shubham Jain who showed their kind concern and consideration regarding my research. My due thanks to Dr. S.M Holkar, Dr. Sanjay Salsandkar, Mr. Pavan Yadav, Mr. Rajat Nagda, Mr. Ajay Nagpurkar, Mrs. Meena Yadav, Mr. Kamal Yadav, and all the institutionalized friends for their timely help rendered throughout my work.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice among patients admitted with addiction to tobacco and alcohol

REFERENCES

- 1.Samet JM. Gender Women and Tobacco Epidemic. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.hqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599511_eng.pdf .

- 2.Murthy P. Psychosocial Interventions for Persons with Substance Abuse. National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/de-addiction/CAM/Psychosocialintervention_2.pdf .

- 3.Reddy KS, Gupta PC. Report on Tobacco Control in India.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laronde DM, Hislop TG, Elwood JM, Rosin MP. Oral cancer: Just the facts. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicotine and Addiction. ASH Fact Sheets. 2012. May, [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 16]. Available from: http://www.ash.org.uk .

- 6.Schaef AW. When Society Becomes an Addict. New York: Harper Collins; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Tobacco Fact Sheet. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/index.html#content .

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Press; 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 02.]. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014 Edition. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112736/1/9789240692763 engpdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Report of the Working Group on Disease Burden for 12th Five Year Plan. Working Group on Disease Burden: Non Communicable Diseases. Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pednekar MS, Sansone G, Gupta PC. Association of alcohol, alcohol and tobacco with mortality: Findings from a prospective cohort study in Mumbai (Bombay), India. Alcohol. 2012;46:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indiana Prevention Resource Centre (IPRC) Alcohol, Tobacco and other Drug use by Indiana Children and Adolescents. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Prevention Resource Centre; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobacco and Alcohol: Knowledge, Beliefs and Attitudes. Survey Question Bank. East Midlands Public Health Observatory. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Prezzemolo R, Protti AS, Cochand S, Monney G, et al. ‘Pick-Klop’ a group smoking cessation game. J Groups Addict Recovery. 2010;5:183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambkin FK. NSW Health Drug and Alcohol Psychosocial Interventions Professional Practice Guidelines. NSW Department of Health. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apodaca TR, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bibliotherapy for alcohol problems. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59:289–304. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ames SC, Patten CA, Werch CE, Schroeder DR, Stevens SR, Fredrickson PA, et al. Expressive writing as a smoking cessation treatment adjunct for young adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:185–94. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foulds J, Delnevo C, Ziedonis DM, Steinberg MB. Handbook of the Medical Consequences of Alcohol and Drug Abuse. USA: The Haworth Press, Inc; 2008. Health effects of tobacco, nicotine, and exposure to tobacco smoke pollution; pp. 423–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Ng F, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, et al. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for major depressive disorder: Population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:322–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siahpush M. Socioeconomic status and tobacco expenditure among Australian households: Results from the 1998-99 household expenditure survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:798–801. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Critchley JA, Unal B. Health effects associated with smokeless tobacco: A systematic review. Thorax. 2003;58:435–43. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:315–27. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anjum Q, Ahmed F, Ashfaq T. Knowledge, attitude and perception of water pipe smoking (Shisha) among adolescents aged 14-19 years. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:312–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina AJ, Fernández T, Fernández D, Delgado M, de Abajo S, Martín V, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about tobacco use after an educative intervention in health sciences' students. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32:862–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbadoro P, Lucrezi D, Prospero E, Annino I. Improvement of knowledge, attitude, and behavior about oral health in a population of alcohol addicted persons. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:347–50. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salaudeen A, Musa O, Akande T, Bolarinwa O. Effects of health education on cigarette smoking habits of young adults in tertiary institutions in a Northern Nigerian state. Health Sci J. 2011;5:216–28. [Google Scholar]