Abstract

Background:

To cope with the challenges in the health-care delivery system and to guarantee the quality of care rendered and client satisfaction on the care received, it is important to know how satisfied health-care workers are with their quality of life, job and what characteristics influence their quality of life. This study was undertaken in a tertiary care hospital to assess the same using validated questionnaires.

Aim:

This study aims to study the quality of life among the health workers (doctors and nurses) of a large multispecialty tertiary care hospital and the psychosocial factors influencing it.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 200 health-care workers with their background demographic data were assessed using quality of life questionnaire and occupational stress inventory. The data compiled were analyzed with appropriate statistical methods.

Results:

The overall quality of life among the study population was average, and the mean prevalence of occupational stress level was of mild level. There was a correlation between domains of occupational stress and domains of quality of life of health-care workers.

Conclusion:

Study findings revealed that overall perception of quality of life was average, overall stress level of health-care workers was moderately elevated and majority showed average coping resources.

Keywords: Health-care workers, psychosocial factors, quality of life

The WHO defines quality of life as an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. This definition highlights the view that quality of life is subjective, includes both positive and negative facets of life and is multidimensional in nature.[1]

Although the practice of medicine can be meaningful and personally fulfilling, it is demanding and stressful too. Hospitals are characterized by a high level of work-related stress, a factor known to increase the risk of low quality of life.[2,3,4,5] Results of studies suggest that many health-care workers experience professional burnout, a syndrome characterized by an emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment.[6,7,8] Although difficult to correctly measure and quantify, findings of recent studies suggest that burnout may erode professionalism, influence quality of patient care, increase the risk for errors, and promote early retirement.[9,10,11,12,13] Burnout also seems to have adverse personal consequences for health-care workers, including contributions to broken relationships, problematic alcohol and other substance use, and suicidal ideation.[14,15] In general, they become frustrated about their inability to complete their work to their professional satisfaction and express wishes to leave the nursing profession.[16]

Not only are physicians role models in the general community with regard to lifestyle and drinking but also physicians' own health practices may affect how they counsel patients.[17,18] It has been shown that physicians fail to detect or treat 40%–60% of cases of depression in their patients.[19,20,21] Furthermore and consistent with this, approximately 40% of individuals who die by suicide had contacted their primary care physician within a month of their suicide, without eliciting the attention of, or proper action by, the treating physician.[22]

Finally, an increasing body of research shows that distressed or mentally ill physicians unintentionally put patients at risk of harm and that this particularly applies to depressed physicians.[23,24] A prospective and observational study found that depressed medical residents made medication errors six times more often than nondepressed residents, an effect that, interestingly, was not duplicated among burned out residents.[25] A review in the Lancet stated that mental health problems among physicians constitute an important and under-estimated political health factor because their well-being seems to be an overlooked quality indicator of all health-care systems.[9]

Yu et al. conducted a cross-sectional research to explore the quality of life and job satisfaction and their interrelationships among 1020 nurses.[26] There was a strong positive correlation between job satisfaction and quality of life. Lee identified correlations between fatigue and quality of life among 294 clinical nurses in Korea.[27] The relationship between fatigue and quality of life revealed a significant negative correlation.

Chiu et al. studied the workability and its relationship with quality of life of 1534 clinical nurses in Taiwan.[28] For improving and maintaining the workability of nurses, measures such as increasing the ability to cope with the job's mental needs for young nurses, and improving the job design to decrease physical workload for senior nurses were recommended. Delmas and Duquette examined the relations between hardiness, coping strategies and quality of life at job of French nurses working in the ICU and to examine the mediating effect of coping strategies between hardiness and quality of life at job.[29] Regression analysis showed that problem-solving coping strategies had a mediating effect between a sense of commitment, a sense of mastery, and quality of life at work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This observational study was carried out in a large urban tertiary care center having almost all specialty and superspecialty services. Two hundred health-care workers (doctors and nurses) working for a minimum of the past 6 months and willing to participate were included in the study. Individuals with a prior history of mental illness were not included. The interviewer introduced himself to the subjects, as a doctor conducting a study on quality of life among health-care workers and informed consent was obtained. The three-part questionnaires were self-administered, anonymous, and voluntary. The first part was the quality of life questionnaire (QLQ) to assess the quality of life of health-care worker working in the hospital.[30] The second part was occupational stress inventory (Revised) (OSI-R) which was aimed to investigate the occupational stress level as psychological factor affecting quality of life of the participants.[31] The third part was the background demographic data and different social factors affecting quality of life.

The QLQ is composed of a 192 self-report true/false item scale (which includes 15 subscales, a Social Desirability scale, and a Total Quality of Life summative scale score). It can be administered either to a group or individually and can be computer or manually administered and scored. The raw subscale items are converted into T-scores. The QLQ provides an assessment of five major domains as below:

-

General Well-Being

- Material Well-Being (A)

- Physical Well-Being (B)

- Personal Growth (C).

-

Interpersonal Relations

- Marital Relations (D)

- Parent–Child Relations (E)

- Extended Family Relations (F)

- Extrafamilial Relations (G).

-

Organizational Activity

- Altruistic Behavior (H)

- Political Behavior (I).

-

Occupational Activity

- Job Characteristics (J)

- Occupational Relations (K)

- Job Satisfiers (L).

-

Leisure and Recreational Activity

- Creative/Esthetic Behavior (M)

- Sports Activity (N)

- Vacation Behavior (O).

The OSI-R is designed to develop an integrated theoretical model to link three important dimensions and develop generic occupational stress measures that would apply across different occupational levels and environments. The three dimensions are occupational role, personal stress, and personal resources. Each dimension is measured by assessing specific attributes contributing to the overall score and is as below:

-

Occupational Roles Questionnaire

- Role Overload (RO)

- Role Insufficiency (RI)

- Role Ambiguity (RA)

- Role Boundary (RB)

- Responsibility (R)

- Physical Environment (PE).

-

Personal Strain Questionnaire

- Vocational Strain (VS)

- Psychological Strain (PSY)

- Interpersonal Strain (IS)

- Physical Strain (PHS).

-

Personal Resources Questionnaire

- Recreation (RE)

- Self-care (SC)

- Social Support (SS)

- Rational/Cognitive Coping (RC).

The software SPSS version 19.0 was used in this study. Based on the objectives of the study and the hypotheses to be tested descriptive and inferential statistics were used for the statistical analysis of the data. Frequency and percentage were used to analyze the data related to sample characteristics.

RESULTS

There were 200 qualified participants (100 doctors and 100 nurses) aged between 21 and 60 years old. Most of the respondents (44.5%) are aged between 21 and 30 years old, 70% of participants were females and 43.5% were having professional qualification of general nursing and midwifery. Most of the participants (70%) were married of which most (41%) were having two children. About 74.5% of the respondents were having nuclear family. Most of the respondents (45.5%) were working in medical wards and 78% of total participants used to work 8–10 h. Among the doctors, 60% were male, 87 doctors were MBBS (including residents working in the specific department) and 13 were postgraduates working as consultants. All nurses were females and a larger portion of them (87%) were general nurses.

The mean T-score of health-care workers' overall quality of life was 47.84. As per interpretive guidelines for T-scores, it is average quality of life.

The mean T score of health-care workers' overall occupational stress was 63.87. As per interpretive guidelines for T-scores, it is mild level of maladaptive stress and strain. Mean T-score of health-care workers, overall coping resources was 51.28. As per interpretive guidelines for T-scores, it is average coping resources.

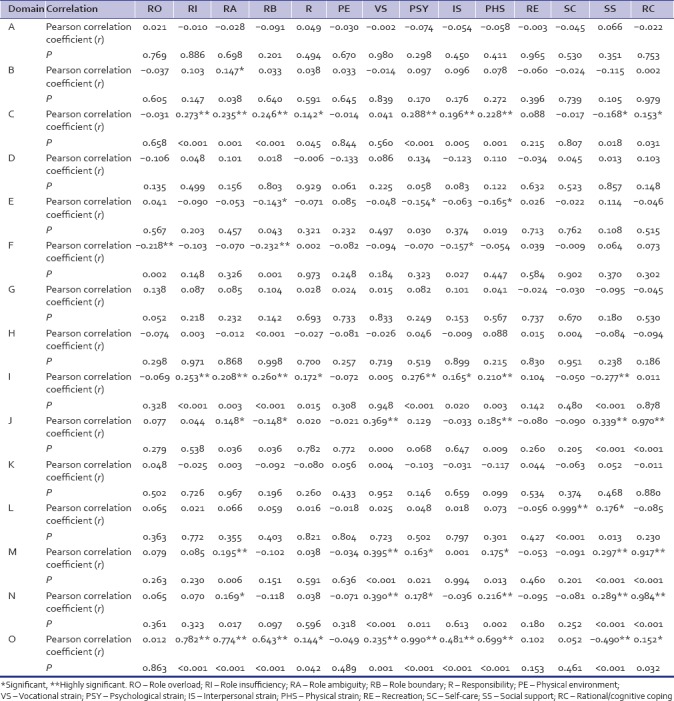

Table 1 shows the results of Pearson correlations that measure the relationship between quality of life of health-care workers and occupational stress level of health-care workers as a psychological variable.

Table 1.

Correlation between quality of life and occupational stress

The correlation of RI, RA, RB, PSY, IS, and PHS with personal growth (C) was found to be statistically significant. The correlation of RO and RB with extended family relations (F) was found to be statistically significant. The correlation of RI, RA, RB, PSY, PHS and SS with political behavior (I) was found to be statistically significant.

The correlation of VS, SS, and RC with job characteristics (J) was found to be statistically significant. The correlation of SC with occupational relations (L) was found to be statistically significant. The correlation of VS and SS and RC with creative esthetic behavior (M) was also found to be statistically significant.

The correlation of VS, PSY, and SS, RC with sports activity (N) was found to be statistically significant. The correlation of RI, RA, RB, VS, PSY, IS, PHS, and SS with vacation behavior (O) was found to be statistically significant.

The association of type of family (nuclear/joint) with physical wellbeing (B) and the association of area of the current work with parent–child relations (E) and vacation behavior (O) also were found to be statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

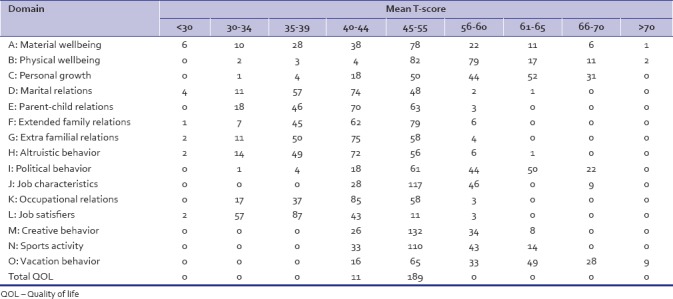

The results of this study revealed that overall quality of life among the study population was average [Table 2]. It was average quality of life in general well-being, leisure, and recreational activity but slightly below the average quality of life in interpersonal relations, organizational activity, and occupational activity. Frequent conflicts among colleagues over decision-making, deciding responsibility for patient-related errors and at times higher unmet expectations from patient's caregivers might be the reasons for slightly below average quality of life in occupational activity.

Table 2.

Quality of life - distribution of quality of life questionnaire score of health-care workers in different domains (A - O)

A similar study by Jovic-Vranes et al. in Serbia had revealed a low level of overall quality of life and job satisfaction in Serbian healthcare workers.[32] This may be due to mostly young study population, fixed working hours of most of the study population, joint family type and most of them having two or less children. Ayers suggested that the job environment should motivate workers to perform at their best and show commitment to the organization, enhancing favorable work conditions to support the organization's mission and thus impacting on quality of life and job satisfaction.[33]

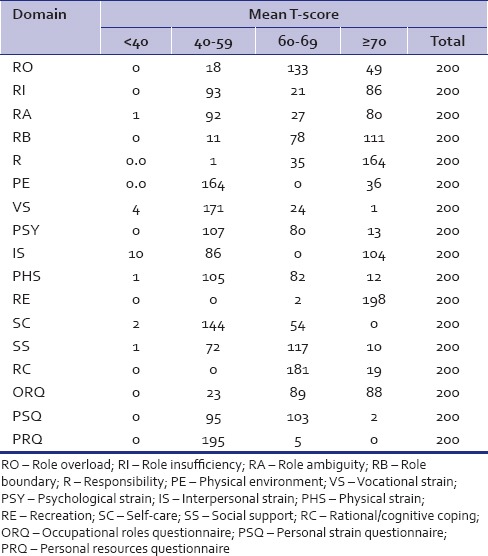

The results, shown in Table 3, reveal that the mean prevalence of occupational stress level among the study population was of the mild level. About 44.5% of the study population was having mild level while 44% subjects were having high level of stress at the occupational sphere. About 51.5% of the study population was having mild level while 47.5% subjects were having no stress at personal level. Nearly 97.5% study population showed average coping resources. Dealing with human suffering, frequent conflicts among colleagues over decision-making, deciding responsibility for patient-related errors, at times higher unmet expectations from patient's caregivers, inclusion of resident doctors and nurses may be reasons for mild to a high level of stress at occupational front. At times, compromising with family and other social needs due to demanding nature of job may be responsible for the mild level of stress at personal front, but young age, family support, and average coping resources might be protective factors. For comparison, the prevalence of perceived stress of the general population in Sweden was around 14%.[34] In Germany, the prevalence of perceived stress in general population was 17.6%.[35] However, in Jordan, 27% of health-care professionals reported high level of stress.[36] Other studies from the USA showed that stress and burn out may affect 25%–60% of physicians.[37,38,39,40] However, although overall stress level of health-care workers in the present study was elevated not at extremely high level.

Table 3.

Occupational stress level - distribution of occupational stress score of health-care workers in different domains

The results shown in Table 1 reveal that there is a correlation between different domains of occupational stress (psychological variable) and different domains of quality of life of health-care workers. This could suggest that planned problem solving is a coping strategy more often used in our study population and the better coping strategy is associated with better quality of life. Vacation behavior (O) as a domain of QOL was positively correlated with PSY. Our study population was found planning vacations with increase in psychological stress at personal front which might be a protective factor against stress. A similar study by Lee had indicated inverse association between direct coping strategies and occupational stress, and a positive association between perceived health status and coping.[41]

This study results revealed that type of family and area of the current work were statistically associated with quality of life through other factors such as marital status, number of children, and duty hours were not associated. The reason could be, in India, support from the joint family system is very significant in playing a dual role for health-care workers. A study of predictors of job satisfaction among doctors, nurses, and auxiliaries in a Norwegian hospital had revealed that positive evaluation of local leadership as the only domain of work that was significant in predicting high quality of life and job satisfaction for all groups.[42]

There were few limitations of the study. The research was focused on self-report measurement where the researcher had to assume that the respondents were truthful. This study was limited by cross-sectional design. Although it was found that there was a significant relationship between quality of life and occupational stress, the causal direction could not be determined. Sample size from different units/wards and various specialty groups were not balanced. Other factors external to the job may affect the quality of life and occupational stress level as confounders, but they were not explored.

CONCLUSION

To cope with the challenges in the health-care delivery system and to guarantee the quality of care rendered and client satisfaction on the care received, it is important to know how satisfied health-care workers are with their QOL and job and what characteristics influence their quality of life. This study revealed that overall perception of quality of life was average, the overall stress level of health-care workers was moderately elevated and majority showed average coping resources. It may be inferred from results that when health-care workers experience high stress, coping ability also increases as a measure to overcome stress.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL): Quality of Life Research. 1993;2:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang EM, Bidewell JW, Huntington AD, Daly J, Johnson A, Wilson H, et al. A survey of role stress, coping and health in Australian and New Zealand hospital nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:1354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman AC, Edwards D, Simonton S, Mehta P. Caregiver stress and burnout in an oncology unit. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:65–80. doi: 10.1017/s1478951506060081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson A, Halabi J. Work related post-traumatic stress as described by Jordanian emergency nurses. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2006;14:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamaideh SH, Mrayyan MT, Mudallal R, Faouri IG, Khasawneh NA. Jordanian nurses' job stressors and social support. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55:40–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. 3rd ed. PaloAlto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spickard A, Jr, Gabbe SG, Christensen JF. Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA. 2002;288:1447–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:463–71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: A missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374:1714–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Jr, Eacker A, Harper W, Power D, Durning SJ, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304:1173–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Satele D, Balch C. Why do surgeons consider leaving practice? J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:421–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balch CM, Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Satele DV, Freischlag JA. Distress and career satisfaction among 14 surgical specialties, comparing academic and private practice settings. Ann Surg. 2011;254:558–68. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318230097e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, Bechamps G, Russell T, Satele D, et al. Special report: Suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146:54–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegney D, Plank A, Parker V. Nursing workloads: The results of a study of Queensland nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2003;11:307–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2003.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank E, Rothenberg R, Lewis C, Belodoff BF. Correlates of physicians' prevention-related practices.Findings from the women physicians' health study. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:359–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:909–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford S, Lewis S, Fallowfield L. Psychological morbidity in newly referred patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00103-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan CP, et al. Effect of reducing interns' weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1829–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302:1294–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, Sharek PJ, Lewin D, Chiang VW, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:488–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hagan J, Richards J. 2nd ed. Wellington, (New Zealand): Doctors Health Advisory Service; 1998. In: Sickness and in Health; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu YJ, Hung SW, Wu YK, Tsai LC, Wang HM, Lin CJ, et al. Job satisfaction and quality of life among hospital nurses in the Yunlin-Chiayi area. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2008;55:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JI, Park SH, Moon JM, Park KA, Kim KO, Jeong HJ, et al. Fatigue and quality of life in clinical nurses. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2004;11:317–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu MC, Wang MJ, Lu CW, Pan SM, Kumashiro M, Ilmarinen J, et al. Evaluating work ability and quality of life for clinical nurses in Taiwan. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delmas P, Duquette A. Hardiness, coping and quality of life of nurses working in intensive care units. RechSoins Infirm. 2000;60:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans D. Quality of Life Questionnaire. Wendy Cope, M.A, Pearson; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osipow SH. Occupational Stress Inventory-Revised Edition (OSI-R): Professional Manual. USA: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jovic-Vranes A, Bjegović-Mikanović V, Boris V, Natasa M. Job satisfaction in Serbian health care workers who work with disabled patients. Cent Eur J Med. 2008;3:221. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayers DF. Organizational climate in its semiotic aspect: A postmodern community college undergoes renewal. Community Coll Rev. 2005;33:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergdahl J, Bergdahl M. Perceived stress in adults: Prevalence and association of depression, anxiety and medication in a Swedish population. Stress Health. 2002;18:235–41. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E, Klapp BF. Determinants of fatigue and stress. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:238. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boran A, Shawaheen M, Khader Y, Amarin Z, Hill Rice V. Work-related stress among health professionals in Northern Jordan. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62:145–7. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: A prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296:1071–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Poland GA, Menaker R, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:990–5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Shanafelt TD, West CP. Impact of resident well-being and empathy on assessments of faculty physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:52–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, Huschka M, Baile WF, Morrow M, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: Report on the quality of life of members of the society of surgical oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3043–53. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JK. Job stress, coping and health perceptions of Hong Kong primary care nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:86–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krogstad U, Hofoss D, Veenstra M, Hjortdahl P. Predictors of job satisfaction among doctors, nurses and auxiliaries in Norwegian hospitals: Relevance for micro unit culture. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]