Abstract

Background:

India's corporate sector has grown steadily over the past decade, and it is providing a lot of work opportunities to Indian youth. Around 20% of employees in the corporate sector in India smoke cigarettes. In general, addictive behaviors including smoking are associated with certain personality dimensions. Hence, we conducted a study with the aims to assess the level of nicotine dependence in tobacco smokers (working in corporate sector), study their personality profile, and association of their personality traits with continuing smoking behavior.

Materials and Methods:

The study proposal along with its intended aims and objectives was cleared by the Institutional Ethical Review Board. It was a cross-sectional study. We used FTND for level of nicotine dependence and NEO FFI 3 for personality profile along with a structured proforma.

Results:

Most of the clients were of very low to low level of nicotine dependence. As high as 40% of the clients did not even attempt to quit smoking, most common reason for attempt at quitting was health concerns. Major causes of relapse were friends, people at workplace, and nature of work. Clients were high on neuroticism, average on extraversion and openness, and low on agreeableness and conscientiousness. Neuroticism was significantly associated with the level of nicotine dependence. Extraversion and openness were associated with health concerns, while agreeableness and conscientiousness were associated with social factors as a reason to quit. Extraversion and agreeableness were associated with occupational factors and social factors as reasons to relapse.

Conclusion:

Understanding one's personality would be helpful to identify health-enhancing (which help to attempt at quitting) and health-destructive (which were responsible for relapse) behaviors. This can further help in framing interventions that particularly target these personality traits and behaviors.

Keywords: Corporate sector, personality, smoking

The corporate sector is receiving increasing attention in many countries which stems from the importance of the sector in economic performance. India's corporate sector has grown steadily over the past decade, and it is providing a lot of work opportunities to Indian youth. According to the data by Government of India (Annual Survey of Industries by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation), there were 127,957 factories in 2002–2003. The number has increased to 222,120 in 2012–2013. In 2002–2003, 6161,493 employees were working in industries, which have increased to 10,051,626 by 2012–2013. Aside from attractive salaries, the attractive work environment and benefits offered by the corporate sector have motivated many young adults to seek employment in this sector.[1]

Around 20% of employees in the corporate sector in India smoke tobacco-containing cigarettes.[2] Furthermore, findings from Steyn et al. showed that more males as compared to females smoked (44% vs. 11%) in the corporate sector.[3] The smoking behavior in this population is hypothesized to be due to increased stress resulting from strict deadlines and ambitious targets, job insecurity, lack of fixed working hours, and bias from colleagues.[4,5,6]

However, substance use is not a unidimensional or a univariate concept. It is important to identify individual variables, principally personality traits that increase the risk for cigarette smoking. In general, addictive behaviors including smoking are associated with certain personality dimensions.[7] Approach-related traits, i.e., extraversion, novelty seeking, impulsivity, and avoidance-related traits, i.e., neuroticism, harm avoidance, etc., have been most extensively reported to be associated with smoking behavior.[8] A study done by Byrne et al. suggests that personality traits such as neuroticism are associated with smoking and this is found to be irrespective of the stress perceived by the clients.[9,10]

Today, we are still unaware of the smoking behavior, personality attributes, and level of nicotine dependence in the corporate sector in India. Understanding this can help us plan interventions that address the specific needs of this group of people. Hence, this study was undertaken to understand smoking behavior as well as personality profile and nicotine dependence of the people working in the corporate sector.

Aims and objectives

To assess the level of nicotine dependence in tobacco smokers, working in corporate sector

To study their personality profile

To study association of their personality traits with continuing smoking behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical considerations

The study proposal along with its intended aims and objectives was cleared by the Institutional Ethical Review Board. Permission was taken from the human resources department of the corporate office after explaining the study, its objectives, and methodology. Informed consent was obtained from all clients who voluntarily took part in this study. All data were handled confidentially.

Study design

It was a cross-sectional study. A total of 200 adults between 18 and 45 years of age, who were working in corporate sector and were tobacco smokers and nicotine dependent according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria were selected. Clients not willing to give informed consent and medically unstable clients were excluded from the study.

Study tools

DSM IV-TR was used to diagnose nicotine dependence in smokers. Structured pro forma to assess sociodemographic profile, history of quit attempts, reasons to quit smoking, and reasons for relapse was used.

Fagerstrom's test for nicotine dependence

This is the most commonly used quantitative measure of nicotine dependence.[11] This scale was used as it mainly assesses the nicotine dependence in tobacco smokers also the overall score estimates the tobacco liking and may provide a stronger measure of physical dependence. The scale consists of six items. Items are summed and the possible scores range from 0 to 10. More the score on this questionnaire, higher is the level of dependence. Fagerstrom's test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) also showed good sensitivity (0.75) and specificity (0.80) in a study done in Japanese population, suggesting that it is a valid and reliable test.[12] One Indian study has used FTND for predicting quitting behavior with special reference to nicotine dependence among adults. They concluded that plan for quitting should be developed depending on the FTND score of an individual.[13]

NEO Five-Factor Inventory-3

It is a standard questionnaire of the five-factor model (FFM) of personality. It is a concise measure of the five major domains of personality (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness).[14] This scale was used in this study as the FFM has shown to be useful to assess the personality in industrial setting also it has demonstrated effectiveness in the prediction of risk-taking behavior.[15] Internal Consistency of the scale ranges from 0.66 to 0.88. Two-week retest reliability for NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) is reported as 0.89, 0.86, 0.88, 0.86, and 0.90 for N (neuroticism), E (extraversion), O (openness), A (agreeableness), and C (conscientiousness), respectively, 6-month test–retest reliabilities of 0.80, 0.86, 0.87, 0.80, and 0.85 for N, E, O, A, and C, respectively.[16] NEO-FFI has been used in Indian setting before in multiple studies. For example, in one of the Indian studies, NEO-FFI was used to find personality correlates of mindfulness,[17] while other study has used it to analyze the relationship between study habits and personality in Indian students.[18]

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic profile, level of nicotine dependence by FTND, reasons to quit smoking, and reasons for relapse were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For personality assessment by NEO-FFI-3, T score of each trait was calculated using the standard method. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the association of level of nicotine dependence with personality traits. Independent sample t-test was used for analyzing associations of reasons to quit smoking and reasons for relapse with personality traits.

RESULTS

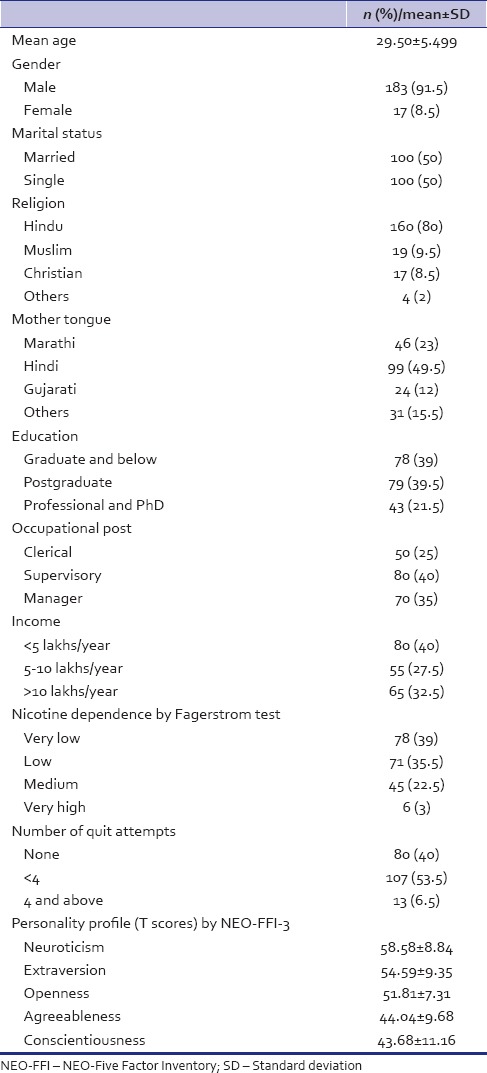

Mean age of the study population was 29.50 years (standard deviation [SD] = 5.499). Out of 200 clients, 91.5% were males, 8.5% were females, 50% were married, and 50% were single. The study population included predominantly Hindu (80%), followed by Muslim (9.5%), Christian (8.5%), and Jain (2%). Of all the clients, 25% occupied clerical posts (peon, clerk, and junior officer), 40% occupied supervisory (senior officer and supervisor) posts, and 35% managerial posts (manager, CEO, and director) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile, Nicotine dependence and Personality profile

Most of the clients (39%) had very low nicotine dependence according to Fagerstrom test [Table 1], followed by low dependence (35.5%) which was followed by medium dependence (22.5%). The mean score of nicotine dependence was 2.97 (SD = 2.17).

Most of the clients did not try to quit even once (40%). However, among those who tried quitting, 89.16% tried <4 times and only 10.83% tried >4 times [Table 1].

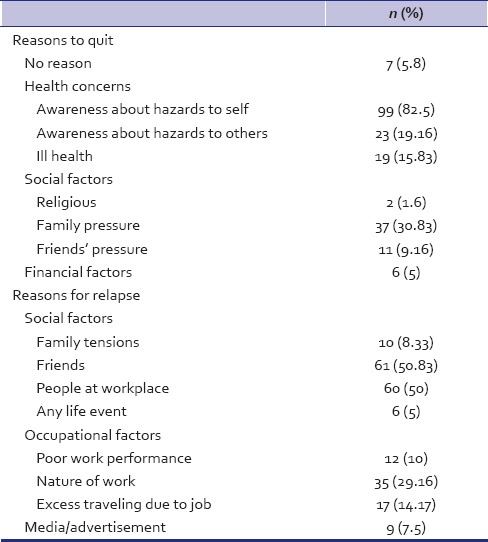

The reasons to quit were grouped as health concerns (awareness about hazards to self and others and ill health), social factors (religious, friends, and family pressure), and financial factors. Of those who tried to quit (n = 120), most (82.5%) attempted quitting due to awareness about hazards to self-followed by family pressure (30.83%), followed by awareness about hazards to others (19.6%). Remaining 15.83% of the clients attempted quitting due to ill health and 9.16% due to friends' pressure [Table 2].

Table 2.

Reasons to quit and relapse (n=120)

Reasons to relapse were grouped as social factors (family tensions, friends, people at workplace, and any life event), occupational factors (poor work performance, nature of work, and excess traveling due to job), and media/advertisements. Most common reasons to restart smoking were due to the influence of people at workplace (50%) and friends (50.83%), followed by nature of work (29.16%) and excess traveling due to job (14.17%). Media/advertisements were responsible in 7.5% of the clients [Table 2].

Personality profile was assessed using NEO-FFI-3 [Table 2]. Clients in this study were, in general, high on neuroticism (t = 58.58), average on extraversion (54.59), and openness (51.85) while being low on agreeableness (44.04) and conscientiousness (43.68). The difference between T scores of males and females was not statistically significant.

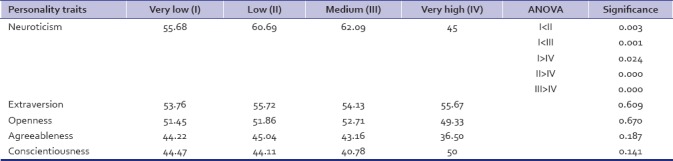

Association between nicotine dependence by Fagerstrom test (grouped as very low, low, medium, and high) and T scores of personality traits was assessed using ANOVA test [Table 3]. As mentioned in the table, mean score of neuroticism was significantly more for medium and low level of nicotine dependence than for very low level. However, mean score for neuroticism was least for those who had very high level of dependence.

Table 3.

Association of nicotine dependence with personality factors using ANOVA

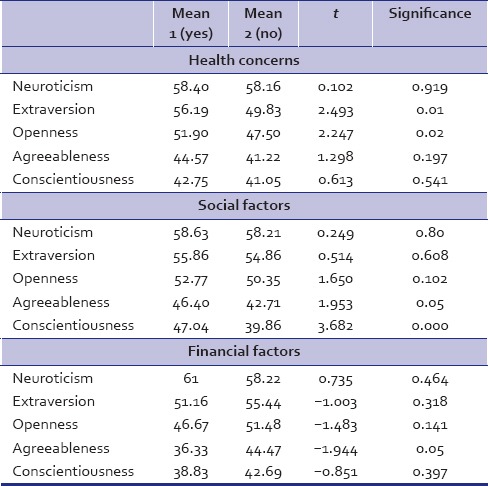

Associations between personality traits and reasons to quit and relapse were assessed using independent sample t-test [Table 4]. Clients scored significantly more on extraversion and openness who used health concerns as a reason to quit than those who did not use it. Agreeableness as a personality trait was associated with social factors and financial factors as a reason to quit. Those who used social factors and those who did not use financial factors scored significantly more on agreeableness. Conscientiousness was significantly associated with social factors. Clients who used social factors as a reason to quit scored significantly more on conscientiousness than those who did not use it.

Table 4.

Associations of personality traits and reasons to quit (t-test)

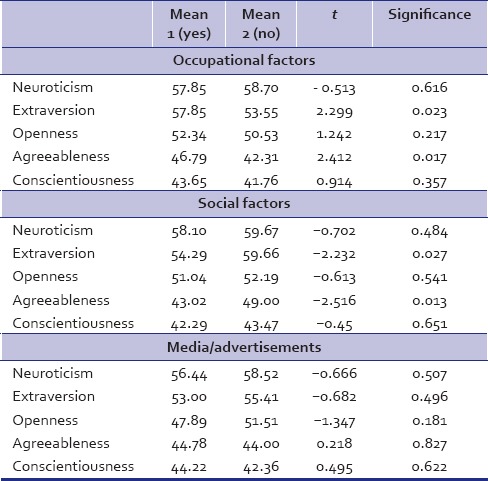

Associations between personality traits and reasons for relapse were assessed using an independent sample t-test [Table 5]. Extraversion and agreeableness were associated with occupational factors and social factors. Those who scored more on extraversion and agreeableness relapsed due to occupational factors and those who scored less on extraversion and agreeableness relapsed due to social factors.

Table 5.

Associations of personality traits and reasons for relapse (t-test)

DISCUSSION

Corporate sector has grown steadily, and it provides a lot of work opportunities to youth along with attractive salaries and a striking work environment. However, as every coin has two sides, the corporate sector has also been associated with increased stress, substance use, and other lifestyle-related problems.

Not many studies have addressed the issue of smoking in corporate sector though it is the most vulnerable set-up as far as addictive behaviors are concerned, especially tobacco smoking and alcoholism. As per a study, nearly 20% of the employees in the Indian corporate sector smoke cigarettes.[2] According to another study done by Steyn et al., almost 11% of females in corporate sector smoke.[3] Our study incorporated 183 (91.5%) males and 17 (8.5%) females [Table 1].

The mean score of Fagerstroms test in our study was around 3, which is categorized as a low level of nicotine dependence. Most of the clients were of very low to low level of nicotine dependence according to Fagerstrom test [Table 1]. In a study done by Heatherton et al.,[11] a number of cigarettes smoked per day and the time to the first cigarette of the day has maximum effect on the score of the nicotine dependence. The corporate set-up where our study was done had stringent rules about smoking, i.e., clients were allowed to smoke only in a specific area (smoking zone) which was on the third floor of one of the buildings. Hence, it was difficult for clients to frequently go and smoke in the identified smoking zone. This strategy used by the employers has possibly affected the number of cigarettes smoked per day, reflecting in the lower levels of nicotine dependence seen in our clients. Thus, the effect of having a different smoking zone, on smoking behavior in corporate sector, needs to be studied further.

A great matter of concern is that 40% did not attempt to quit even once in their lifetime before assessment [Table 2]. Nevertheless, 60% of the study population tried to quit smoking at least once. Among those who tried to quit, most of the clients tried <4 times and a few tried >4 times. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data suggests that, in the Indian population, 43.2% of adults have made an effort to quit tobacco in general, while in the state of Maharashtra, only 29.5% have made an effort.[19] It was seen in a previous study that better educational attainment and better employment were progressively associated with increased attempts to quit.[20] In this study as well, the clients were highly educated which might be the reason for a higher quit rate as compared to general population.

A higher level of education and quality of employment possibly expose an individual to a greater knowledge regarding the harmful effects of smoking (through media and educational materials). This was reflected in the reasons for attempting to quit in our study. Approximately 50% of those who attempted to quit were aware of some of the harmful effects of smoking and they tried to quit as a result of that [Table 1], which was in accordance with the previous studies.[21,22] This also signifies that education and awareness programs about the ill effects of smoking behavior are partly successful at least in certain vulnerable populations and the same should be carried out on a larger scale.

Most of the clients reported that a major cause for relapse was because of friends or people at workplace [Table 1]. Industrialization has coincided with an increase in time spent with and identification with same-age peers.[23] In the corporate sector, an individual spends as much as 8–12 active hours each day with the people at workplace and hence they can be considered as peers. This group of peers (friends and people at workplace) has contributed in relapse when the clients are trying to abstain. Hence, in this high-risk environment of corporate sector, peer pressure is an important contributor for relapse of smoking behavior. Hence, strategic and planned actions focusing on this particular peer group are required as a part of antismoking programs, as confirmed by previous studies.[24,25] Furthermore, half of them relapsed due to nature of work which included stress due to deadlines, altercations with colleagues over work issues, shift duties, and traveling due to work. This finding implicates that it would be beneficial to conduct workshops for stress management and teaching them to maintain a cohesive healthy environment. This may reduce the employees' smoking, and in turn, will improve the productivity and overall health.

Certain personality dimensions have been associated with aspects of addictive behaviors in general and with cigarette smoking behavior specifically.[7] Clients included in this study were high on neuroticism, average on extraversion and openness, and low on agreeableness and conscientiousness [Table 1]. While we had no comparator group of nonsmokers, the personality profile of our sample was similar to that of smokers in the study done by Terracciano et al. This study too showed that, in comparison to nonsmokers, the smokers scored higher on neuroticism and lowered on conscientiousness.[26]

Avoidance-related traits such as neuroticism comprise facets of anxiety, negative affect (i.e. depression), and anger. It is possible that individuals who score high on measures of avoidance-related traits tend to smoke to relieve high basal levels of anxiety, negative affect with nicotine, thus giving rise to the self-medication hypothesis of nicotine use.[27] As per this hypothesis, nicotine products are used not to enhance positive affect (as seen in the classical addiction paradigms) but to relieve negative affect by self-medication.[28,29] Hence, it follows that practices that enable these individuals to regulate and decrease negative affect would possibly help decrease smoking behavior. This emphasizes the role of psychotherapeutic interventions that deal with enabling healthy cognitive styles of thinking to help these people avoid anxiety and negative affect. Neuroticism was significantly more for a higher level of nicotine dependence up to the medium level of dependence [Table 2]. However, mean score for neuroticism was least for those who had a very high level of dependence. This could be because very few clients (3%) in our study had very high nicotine dependence which would have confounded the finding. Alternatively, this suggests that only personality trait of neuroticism may not contribute significantly to very high level of dependence where biological factors (such as dopamine and reward system) would be involved more in comparison to psychological and social factors.

Knowing about the personality traits responsible for quitting for a particular reason and personality traits for relapse will guide us to formulate different psychotherapeutic interventions as earlier studied by Conrod et al.[30] In our study, it was seen that greater score on extraversion and openness was associated with health concerns as a reason to quit [Table 3]. This can be understandable as clients will have more knowledge about the harmful effects of smoking due to these traits. In our study, those who scored more on agreeableness had tried to quit due to social factors such as pressure from family or friends. This could be explained as agreeable persons being soft-hearted, trusting, forgiving, and gullible are more susceptible to social pressure. Clients who scored significantly more on conscientiousness had used social factors as a reason to quit than those who had not which can be due to their higher propensity to follow socially prescribed norms.

Clients who scored higher on extraversion and agreeableness relapsed due to occupational factors such as poor work performance, nature of work, and excess traveling due to job [Table 4]. It is known that those who score low on agreeableness are cynical, suspicious, and uncooperative. Similarly, participants having low scores on extraversion are those who are more reserved, task-oriented, lethargic, and quiet. Clients who scored less on these two personality traits relapsed due to social factors which include peers and family tensions.

Our study had a few limitations. In this study, psychiatric comorbidities were not considered which may have influenced the smoking behavior. Also, as this study was a cross-sectional study, it could not predict a causal relationship between personality and smoking and level of nicotine dependence. However, it can guide researchers in formulating further longitudinal studies.

To conclude the findings of our study, most of the clients were of very low to low level of nicotine dependence. As high as 40% of the clients did not even attempt to quit smoking, so it is important to educate these individuals and motivate them to quit smoking. Most common reason for attempt at quitting was health concerns. Hence, use of education and awareness about hazards to self and others is advisable while motivating these clients. Major causes of relapse were friends, people at workplace, and nature of work. Clients were high on neuroticism, average on extraversion and openness, and low on agreeableness and conscientiousness. Neuroticism was significantly associated with the level of nicotine dependence. Different personality traits were associated with different reasons to quit and reasons to relapse.

These findings imply that it is important to conduct psychotherapeutic interventions focusing particularly on the stress management and motivational programs focusing on health hazards of smoking. Understanding one's personality would be helpful to identify health-enhancing (which help to attempt at quitting) and health-destructive (which were responsible for relapse) behaviors. This can further help in framing interventions that particularly target these personality traits and behaviors. Not taking personality traits into account while planning interventions for smoking cessation in a corporate sector may lead to failure of the intervention. Hence, integration of mental health services becomes important in corporate sector for smoking cessation interventions. This study also guides researchers to study the effect of having a different smoking zone, on smoking behavior in corporate sector.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma S. BPO Industry in India – A Report. 2004. Available from: http://www.BPOindia.org/research/bpo-in-india.html .

- 2.20% MNC Executives Smoke Regularly Finds Hospital Study – Hindustan Times. Available from: http://www.hindustantimes.com/ india-news/newdelhi/20-mnc-executives-smoke-regularly-finds-hospital-study/article1-704615.aspx .

- 3.Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R, Saloojee Y. Tobacco use in South Africans during 1998: The first demographic and health survey. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2002;9:161–70. doi: 10.1177/174182670200900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steptoe A, Wardle J, Pollard TM, Canaan L, Davies GJ. Stress, social support and health-related behavior: A study of smoking, alcohol consumption and physical exercise. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41:171–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(96)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaid M. Exploring the Lives of Youth in the BPO Sector: Findings from a Study in Gurgaon, Health and Population Innovation Fellowship Programme Working Paper, No. 10. New Delhi: Population Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra BS. Study on stress and prevention of stress; with reference of corporate professionals. Int J Adv Res Manage Soc Sci. 2015;4:66–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munafò M, Johnstone E, Murphy M, Walton R. New directions in the genetic mechanisms underlying nicotine addiction. Addict Biol. 2001;6:109–17. doi: 10.1080/13556210020040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munafò MR, Zetteler JI, Clark TG. Personality and smoking status: A meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:405–13. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne DG, Byrne AE, Reinhart MI. Personality, stress and the decision to commence cigarette smoking in adolescence. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00074-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin R, Bono A. Big five personality traits and smoking persistence over 12 years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;140:e71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meneses-Gaya IC, Zuardi AW, Loureiro SR, Crippa JA. Psychometric properties of the fagerström test for nicotine dependence. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35:73–82. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam K, Saha I, Saha R, Samim Khan SA, Thakur R, Shivam S, et al. Predictors of quitting behaviour with special reference to nicotine dependence among adult tobacco-users in a Slum of Burdwan district, West Bengal, India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:638–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrae RR, Costa P. Brief Versions of the NEO-PI-3. J Individual Differences. 2007;28:116–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skeel RL, Neudecker J, Pilarski C, Pytlak K. The utility of personality variables and behaviorally-based measures in the prediction of risk-taking behavior. Pers Individ Differ. 2007;43:203–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCrae RR, Costa PT. N.Florida Ave: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2010. NEO Inventories for the NEO Personality Inventory – 3, NEO Five Factor Inventory – 3, NEO Personality Inventory – Revised, Professional Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menon P, Doddoli S, Singh S, Bhogal RS. Personality Correlates of Mindfulness: A Study in an Indian Setting. [Last accessed on 2017 Sep 04];Yoga Mimamsa. 2014 46:29–36. Available from: http://www.ym-kdham.in/text.asp?2014/46/1/29/137844 . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chouhan P, Kackar A. Relationship between study habits and neo five factor inventory ‘S factors among private and government school student. Int J Indian Psychol. 2016;4:84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC – GTSSData: FactSheets. Available from: http://www.nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSData/Ancillary/DataReports.aspx?CAID=1 .

- 20.Srivastava S, Malhotra S, Harries AD, Lal P, Arora M. Correlates of tobacco quit attempts and cessation in the adult population of India: Secondary analysis of the global adult tobacco survey, 2009-10. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallus S, Muttarak R, Franchi M, Pacifici R, Colombo P, Boffetta P, et al. Why do smokers quit? Eur J Cancer Prev. 2013;22:96–101. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283552da8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCaul KD, Hockemeyer JR, Johnson RJ, Zetocha K, Quinlan K, Glasgow RE, et al. Motivation to quit using cigarettes: A review. Addict Behav. 2006;31:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crockett LJ. Cultural, historical, and subcultural contexts of adolescence: Implications for health and development. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs J, Hurrelman K, editors. Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1997. pp. 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloor M, Frankland J, Langdon NP, Robinson M, Allerston S, Catherine A, et al. A controlled evaluation of an intensive, peer- led, schools-based, anti-smoking programme. Health Educ J. 1999;58:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2012. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. 6, Efforts to Prevent and Reduce Tobacco Use Among Young People. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99240/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terracciano A, Löckenhoff CE, Crum RM, Bienvenu OJ, Costa PT., Jr Five-factor model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eysenck HJ, Grossarth-Maticek R, Everitt B. Personality, stress, smoking, and genetic predisposition as synergistic risk factors for cancer and coronary heart disease. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 1991;26:309–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02691067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert D, Rabinovich N, Malpass D, Mrnak J, Riise H, Devlesc Howard M, et al. Effects of nicotine on affect are moderated by stressor proximity and frequency, positive alternatives, and smoker status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1171–83. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tizabi Y, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Louis VA, Clark E, Jr, Janowsky DS, et al. Antidepressant effects of nicotine in an animal model of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:193–9. doi: 10.1007/s002130050879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Côté S, Fontaine V, Dongier M, et al. Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:231–42. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]