Abstract

Background:

Medical studies are very challenging. As a result of the demands placed on them, students may be under stress, and this may affect their behavior and performance. Not many Indian studies have delved into this problem.

Aim:

The aim of the study is to assess the levels of stress and its associated adverse behavioral effects in undergraduate medical students in a tertiary care medical college.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study included medical students from 2nd to 4th year who had given informed consent to participate in the study. Students were assessed with a semi-structured questionnaire, students stress scale (SSS), perceived stress questionnaire, and risk-taking and self-harm (RT and SH) inventory.

Results:

A total of 405 students (153 males and 252 females) participated in the study. There were no significant differences in the age, perceived family support, religious practices, physical activity, and SSS scores of the male and female students. A significantly higher score was obtained by boys as compared to the girls on the scores of the RT subscale and total score on RT and SH inventory. However, girls obtained significantly higher scores as compared to boys on the perceived stress scale. Among girls, 23.4% reported high stress, 63.5% had moderate stress, and 13.1% reported low stress. Among boys, 11.1% reported high stress, 68.6% had moderate stress, and 20.3% reported low stress. The difference was statistically significant.

Conclusions:

The majority of Medical undergraduates were under stress; however, the majority perceived themselves to be under moderate stress. Male students had higher scores on RT and SH inventory as compared to females. There is an urgent need to study the causes and devise effective management and preventive measures to avoid the harmful long-term effects of stress on their careers and well-being.

Keywords: Alcohol use, medical students, perceived stress, risk-taking, self-harm, stress

“Life minus stress is death.”

- Hans Selye

Stress is the psychological and physical state that results when the resources of an individual are not sufficient to cope with the demands and pressures of a situation. This can lead to negative cognition, negative emotions, and maladaptive behaviors.[1] Stressors are perceived differently by different individuals. A stressor which causes distress to one may hardly be stressful at all to another. The 5½ years undergraduate medical training period requires long hours of hard work, tremendous levels of commitment, and a large amount of responsibility. This can be extremely stressful and exhausting, sometimes resulting in poor learning ability, and below average academic performances. Additional factors such as moving away from a protective home environment or migration to another state can add to this stress.

Various methods for evaluating stress level and ranking causative factors have been developed in research on stress. The method developed by Rahe and Arthur is probably the most popular method. In this method, evaluation of stress level is done by quantifying life changes induced by stressors using life change units.[2] Since stressful life events can increase the probability of illness by utilizing Holms and Rahe's method, we can estimate the probability of illness based on the intensity of stressful events in the recent past. Therefore, apart from an objective estimation of stress levels based on factual life events, this method also provides the avenue of interpreting an individual's stress-induced life change regarding its effect on physical health.[3,4]

Numerous studies have been reported that medical students suffer from higher perceived stress compared to students in other academic fields and the general population.[5,6]

The negative consequences of the long and stressful medical education on the psychological status of medical students have highlighted in several studies. Studies indicate that approximately 10% of medical students have depression, and 6% have a history of suicidal ideation.[7] Excessive stress levels may also produce a feeling of loneliness and nervousness, sleeplessness, excessive distress,[8] and reduced well-being.[9] Distress resulting from stressors can adversely affect professional development and negatively impact empathic and humanitarian attitudes among medical students.[10,11]

How boys and girls cope with perceived stressful situations may also differ. Boys may go for more of externalizing behaviors such as substance abuse, while girls cope with more internalizing tendencies such as self-harm (SH). Risk-taking (RT) refers to engagement in behaviors that are associated with some probability of undesirable results.[12] The easy availability of a range of substances of abuse and an environment where they may witness faulty or unhealthy coping mechanisms by seniors may push them to seek alternate maladaptive coping methods including RT and even SH behaviors. SH is an act with a nonfatal outcome. Here, an individual deliberately initiates behaviors such as cutting themselves or ingesting poison with the intention of causing harm to themselves.[13] SH is a global health problem, and one of the strongest predictors of completed suicide[14] It has been reported that the prevalence rate of SH in adolescents is 8%, with more girls than boys[15] A cross-sectional study of 321 medical students reported highly significant levels of perceived stress levels and emotional distress in them.[16] The suicide rate among male and female doctors is >40% and 130% higher, respectively than among men and women in the general population.[17,18] The increased suicidal risk among doctors probably begins during medical studies since studies in different countries indicate that attempted suicide among medical students is higher than in the age-matched population.[19,20] In addition, suicidal ideation is an established predictor of attempted suicide, and few studies have reported high prevalence (3%–15%) of suicidal ideation in medical students.[21,22] Not many Indian studies have delved into this problem of stress and its adverse consequences such as RT and suicidal ideation in medical students.

The current study is designed to find out the prevalence of stress and its consequences such as RT and SH behaviors, in medical students in an urban medical college in Maharashtra. The study aims to detect the presence of stressors, the difference in the way they perceive stress, and the most common, faulty or unhealthy coping styles, so that preventive measures can be taken as early as possible and healthy coping mechanisms can be introduced, as part of the training curriculum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional, analytical study was carried out at a medical college attached to tertiary care hospital and research center. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee. All the subjects gave written informed consent.

Sample

Students undergoing MBBS course from 2nd year to final year, who had given informed consent to participate in the study.

Tools

A semi-structured questionnaire

This was a self-made questionnaire for recording sociodemographic details.

Student stress scale

It is an adaptation of Holmes and Rahe life event scale, modified to college students. It is a 31-item self-report scale in which the participants have to indicate whether they have experienced a specific life event in the past 6 months or expect to experience in the next 6months. The scale is scored by adding the points listed for the checked life events, and the scores roughly indicate the stress levels. Scores of stress up to149 indicate very little stress; 150–199 mild stress; 200–249 moderate stress; 250–299 serious stress and scores of 300 or more indicate major stress. In addition scores of 300 and higher indicate a relatively high health risk, while scores of 150–299 indicate a 50/50 chance of serious health problems within 2 years.[23,24]

Perceived stress scale (PSS)

This is a 10 items scale by Sheldon Cohen, to evaluate the method of individual's perception of the stressor as a stress. It measures the degree to which the situations in life are perceived as stress full. The score ranges from 0 to 40. The answers are graded on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from never = 0, almost never = 1, sometimes = 2, fairly often = 3, to very often = 4. Positively framed questions 4, 5, 7, and 8 are reverse scored, that is never = 4 to very often = 0, and the scores are summed, with higher scores indicating more perceived stress. A score of fourteen or more is regarded as perceived stress.[25,26] The levels of stress were arbitrarily divided as follows: low perceived stress: 0–13, moderate perceived stress: 14–26, and high perceived stress: 27–40. The levels of stress divisions were selected in accordance to similar studies in India.[27,28]

Risk taking and self-harm inventory

This a 27-item inventory to assess the RT and self-harm (SH) behaviors. Two factors emerged from the principal axis factoring, and RT and SH were further validated by a confirmatory factor analysis as related, but different constructs, rather than elements of a single continuum. Inter-item and test-retest reliability were high for both components (Cronbach's alpha = 0.85 and 0.93, rtt= 0.90 and 0.87) and considerable evidence emerged in support of the measure's convergent, concurrent and divergent validity.[29]

Procedure

An introduction to the subject by explaining stress and its impacts was done before starting the study. It was clearly informed to the students that participation in the study was voluntary and was neither connected nor would affect their academic progress in the course. After explaining the purpose and design of the study, written informed consent was obtained for participation in the study from all participants. Thereafter, the semi-structured questionnaire, students stress scale (SSS), perceived stress questionnaire, and RT and self-harm inventory were administered to the students. The rating scales were scored as per the test manual and data entered in Microsoft Excel.

Statistical analysis

We performed all data analyses using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 16) program (IBM, USA). Chi-square and t-tests were run comparing the survey responses of the male and female students. Because the male and female students were not matched in the surveys, the groups were treated as being independent rather than paired.

RESULTS

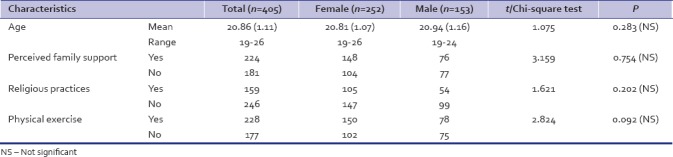

A total of 405 medical students, including 153 male and 252 females, participated in the study. There were no significant differences in the age of the male and female students [Table 1]. There was no significant difference between the two groups on perceived family support, religious practices and physical activity that they routinely performed.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the medical students

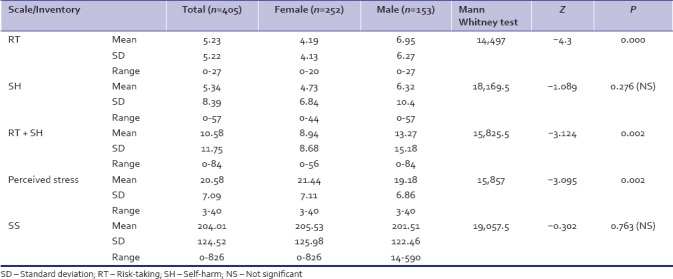

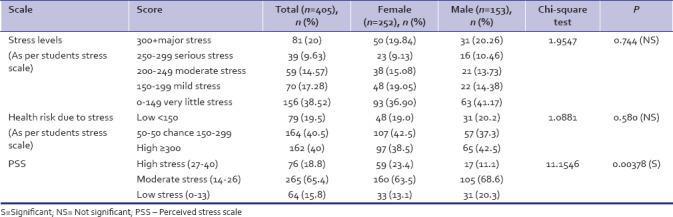

The scores obtained by the students on perceived stress scale, RT, and SH inventory, and SSS are given in Table 2. A significantly higher score was obtained by boys as compared to the girls on the scores of the RT scale, and total score on RT and SH inventory. However, girls obtained significantly higher scores as compared to boys on the perceived stress scale [Table 2]. Further analysis revealed that on the SSS the prevalence of stress in all students was about 61.48%, while 38.52% students were under very little stress, and the prevalence of severe stress was 20% [Table 3]. However, on the PSS, the prevalence of stress in the students was about 84.2% while 15.8% students were under very little stress, and the prevalence of high stress was 18.8%.

Table 2.

Scores obtained by medical students on the risk taking and self-harm inventory, perceived stress scale and students stress scale

Table 3.

Levels of stress in medical students as assessed by Students Stress Scale and Perceived Stress Scale

When Pearson's correlation test of significance (two-tailed) was applied to the SSS and PSS scores and the RT and SH scores, it was found that among male and female MBBS students, scores on SSS, and PSS were significantly correlated to both the RT and SH scores. This clearly indicated that in both genders increased stress increased the possibility of RT and self-harming behavior.

DISCUSSION

Stress in an invariable accompaniment of medical studies. While some amount of stress is required for optimum performance, excessive stress has adverse psychological and physical consequences. In the present study on the student's stress scale, 38.52% of the students were under very little stress while 61.48% were under some amount of stress. This observation is in agreement with a number of earlier studies which also found that the prevalence of stress in medical students varied from 63.8% to >−90%.[30,31,32,33,34,35,36] Contrary results were reported a Malaysian study which reported a low prevalence of stress (16.9%) which they attributed to a program held by their institution to enhance the students coping strategies toward stress.[37]

On the other hand, based on the PSS in our study, a total of 84.2% students were under stress– 65.4% under moderate stress and 18.8% were under severe stress. This was, however, much lower than the findings of 96.8% reported by a previous Indian study[38] and a study at Aga Khan University, Pakistan, which found that >90% students were stressed sometimes during their course. However, our findings are similar to a study from Tamil Nadu which reported that 82% students were under stress – 71.4% under moderate stress and 10.9% were under severe stress.[28] A similar study from Maharashtra reported that 85% 1st year medical students had stress[39] and a study from a medical college at Mumbai showed that 73% had perceived stress.[33] Similarly, in a Thai medical school 61.4% students had experienced some degree of stress.[40]

Few earlier studies also reported that female students had significantly higher stress compared to males, namely 77% versus 64%,[34] 55% versus 45%,[31] and 53.45% versus 46.55%.[35] However, in our study, the findings were not significantly different, though female were slightly more stressed at 63.1% as compared to males 58.8% (Chi-square 0.7335; P = 0.391; not significant). This finding is in agreement with earlier studies[16,36] On the other hand, one study reported that females had a lower risk of stress as compared to males.[37] The inconsistent association of stress and gender could be due to differences in social, economic, and educational environment as well as subjectivity in measuring self-reported stress. Some authors have also suggested that females are more likely to perceive challenging and threatening events as stressful as compared to men.[41]

RT and SH behaviors are clinically, empirically, and conceptually related constructs that are seen commonly in adolescents and young adults and have the potential to result in dangerous outcomes. RT emerges and declines at specific age ranges, most frequently occurring between the ages of 12 and 15 years but declines thereafter.[42] On the other hand, SH occurs over a longer time span, frequently occurring between the ages of 15 and 35 and may persist into adulthood.[43,44] It is important to note that medical studies overlap the period of high SH and RT. SH is usually linked to depressive mood and the reduction of unwanted or unpleasant affect states, whereas RT is associated with a variety of moods including euphoria.[45,46] The presence of peers often increases RT.[42] SH most often occurs in solitude, although one form of SH, Non-suicidal self injury has been noted to be a group behavior for some individuals. With SH, the goal of the behavior is direct, intentional, and physical harm where with RT, the goal is not direct, intentional harm, but the physical damage may result.[43] In the present study, the scores of both RT and SH were on the lower side which was a good sign indicating good coping abilities of the students. The significantly higher RT scores in boys were on the expected lines. The significant correlation on RT and SH scores with both PSS and SSS scores clearly underscores the possible deleterious effects that stress can have on medical students. This finding has important clinical implications. Early detection of high stress in medical students by periodic monitoring can help the students in effectively tackling their stressors. They can thus be saved from slipping into depression and self-harm or RT behavior.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design, in which a causal relationship between the variables cannot be established. Other limitations include the absence of a control group for potential confounders such sources of stress, academic environment, and living circumstances. Longitudinal analysis of the stress model, including personal resources, coping, academic performance, adverse emotional states, and psychiatric assessment remains to be carried out in the future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of medical undergraduates considered themselves to be under stress; however, the majority perceived themselves to be under moderate stress. Male students had higher scores on RT and self-harm inventory as compared to females. There is an urgent need to study the causes and devise effective management and preventive measures to avoid the harmful long-term effects of stress on their careers and well-being.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Institute of Stress. What is Stress? [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 26]. Available from: http://www.stress.org/what-is-stress/

- 2.Rahe RH, Arthur RJ. Life change and illness studies: Past history and future directions. J Human Stress. 1978;4:3–15. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1978.9934972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dargahi H, Mirsaeid SJ, Kooeik S. An assessment of stress-induced life change in students of health sciences: The path toward a coping strategy. Int J Hosp Res. 2012;1:109–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhury S, Srivastava K, Raju MS, Salujha SK. A life events scale for armed forces personnel. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:165–76. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.31580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voltmer E, Kötter T, Spahn C. Perceived medical school stress and the development of behavior and experience patterns in German medical students. Med Teach. 2012;34:840–7. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.706339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, Moutier C, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Jr, et al. Patterns of distress in US medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33:834–9. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.531158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goebert D, Thompson D, Takeshita J, Beach C, Bryson P, Ephgrave K, et al. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: A multischool study. Acad Med. 2009;84:236–41. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819391bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seyedfatemi N, Tafreshi M, Hagani H. Experienced stressors and coping strategies among Iranian nursing students. BMC Nurs. 2007;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gammon J, Morgan-Samuel H. A study to ascertain the effect of structured student tutorial support on student stress, self-esteem and coping. Nurse Educ Pract. 2005;5:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart SM, Lam TH, Betson CL, Wong CM, Wong AM. A prospective analysis of stress and academic performance in the first two years of medical school. Med Educ. 1999;33:243–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hojat M, Glaser K, Xu G, Veloski JJ, Christian EB. Gender comparisons of medical students' psychosocial profiles. Med Educ. 1999;33:342–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyer TW. The development of risk-taking: A multi-perspective view. Dev Rev. 2006;26:291–345. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, de Wilde EJ, Corcoran P, Fekete S, et al. Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: Comparative findings from the child & adolescent self-harm in Europe (CASE) study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:667–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, Lawlor M, Guthrie E, Mackway-Jones K, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: A 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:297–303. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran P, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Olsson C, Borschmann R, Carlin JB, et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood: A population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2012;379:236–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinen I, Bullinger M, Kocalevent RD. Perceived stress in first year medical students – Associations with personal resources and emotional distress. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center C, Davis M, Detre T, Ford DE, Hansbrough W, Hendin H, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: A consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289:3161–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: A quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2295–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schernhammer E. Taking their own lives – The high rate of physician suicide. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2473–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays LR, Cheever T, Patel P. Medical student suicide, 1989-1994. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:553–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tjia J, Givens JL, Shea JA. Factors associated with undertreatment of medical student depression. J Am Coll Health. 2005;53:219–24. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.5.219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med Educ. 2005;39:594–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMeuse K. The relationship between life events and indices of class room performance. Teach Psychol. 1985;12:146–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Insel P, Roth W. Core Concepts in Health. 4th ed. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Co; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health: Claramount Symposium on Applied Social Psychology. Nebury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thangaraj S, D’souza L. Prevalence of stress levels among first year medical undergraduate students. Int J Interdiscip Multidiscip Stud. 2014;1:176–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anandhalakshmi S, Sahityan V, Thilipkumar G, Saravanan A, Thirunavukarasu M. Perceived stress and sources of stress among first-year medical undergraduate students in a private medical college – Tamil Nadu. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2016;6:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vrouva I, Fonagy P, Fearon PR, Roussow T. The risk-taking and self-harm inventory for adolescents: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:852–65. doi: 10.1037/a0020583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaikh BT, Kahloon A, Kazmi M, Khalid H, Nawaz K, Khan N, et al. Students, stress and coping strategies: A case of Pakistani medical school. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17:346–53. doi: 10.1080/13576280400002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaikh S, Shaikh AH, Magsi I. Stress among medical students of university of Interior Sindh. Med Channel. 2010;16:538–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharifirad G, Marjani A, Abdolrahman C, Mostafa Q, Hossein S. Stress among Isfahan medical sciences students. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:402–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Supe AN. A study of stress in medical students at Seth G.S. medical college. J Postgrad Med. 1998;44:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sani M, Mahfouz MS, Bani I, Alsomily AH, Alagi D, Alsomily NY, et al. Prevalence of stress among medical students in Jizan university, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Gulf Med J. 2012;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chauhan HM, Shah HR, Chauhan SH, Chaudhary M. Stress in medical students: A cross sectional study. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2014;5:292–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nandi M, Hazra A, Sarkar S, Mondal R, Ghosal MK. Stress and its risk factors in medical students: An observational study from a medical college in India. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuad MD, Lye MS, Ibrahim N, Ismail SI, Kar PC. Prevalence and risk factors of stress, anxiety and depression among preclinical medical students in university Putra Malaysia in 2014. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2015;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solanky P, Desai B, Kavishwar A, Kantharia SL. Study of psychological stress among undergraduate medical students of government medical college, Surat. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2012;1:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranade A, Kulkarni G, Dhanumali S. Stress study in 1st year medical students. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2015;6:499–503. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saipanish R. Stress among medical students in a Thai medical school. Med Teach. 2003;25:502–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huschka MM, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1435–42. doi: 10.4065/81.11.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gratz K, Chapman A. Freedom from Self-Harm: Overcoming Self-Injury with Skills from DBT and other Treatments. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nock MK, Teper R, Hollander M. Psychological treatment of self-injury among adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:1081–9. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. The role of seeing blood in non-suicidal self-injury. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:466–73. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: What changes, and why? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:51–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]