Abstract

Moyamoya disease is an idiopathic, nonatherosclerotic, noninflammatory, chronic progressive cerebrovascular disease characterized by bilateral stenosis or occlusion of the arteries around the circle of Willis, typically the supraclinoid internal carotid arteries, followed by extensive collateralization, which are prone to thrombosis, aneurysm, and hemorrhage. Secondary moyamoya phenomenon or moyamoya syndrome (MMS) occurs in a wide range of clinical scenarios including prothrombotic states such as sickle cell anemia, but the association with other hemoglobinopathies is less frequently observed. We describe a case of a 25-year-old female with hemoglobin E-beta thalassemia who had a rare presentation of MMS in the form of choreoathetoid movements in the left upper and lower extremities. We describe this association, primarily to emphasize thalassemia as an extremely rare but a potential etiology of MMS. Since MMS is a progressive disease, it is important to diagnose and initiate treatment to prevent worsening of the disease and recurrence of stroke.

KEY WORDS: Choreoathetoid movement, hemoglobin E-beta thalassemia, Moyamoya syndrome

Introduction

“Moyamoya” is a Japanese word which means hazy like a puff of smoke in the air.[1] This term was used to describe the smoky angiographic appearance of tangled, tiny, collateral vasculature which develops as a compensation to reduced cerebral blood flow.[1,2] Classic angiographic findings of moyamoya vessels have been demonstrated in medical conditions such as neurofibromatosis type 1, tuberous sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Down syndrome, infective etiologies, namely, tuberculous meningitis, bacterial meningitis, aplastic anemia, and prothrombotic states such as sickle cell anemia.[3] These are classified as having moyamoya syndrome (MMS). Although moyamoya disease (MMD) is a common cause of transient ischemic stroke in Asian children and young adults, there have been very few cases of MMS in thalassemia published in the literature.[4,5,6]

Case Report

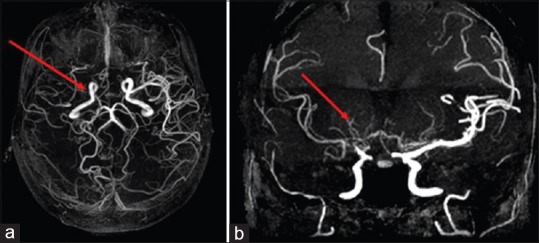

A 25-year-old female, diagnosed with hemoglobin E (HbE)-beta thalassemia at 4 years of age by genetic testing, requiring monthly packed red blood cell transfusion (transfusion dependent) had Xmn1 polymorphism +/-genotype. At 24 years of age, hydroxyurea was initiated, but she responded partially to hydroxyurea therapy (HU), requiring less frequent packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions. After 1 year on HU, she developed irregular, involuntary, twisting, and writhing movements in the left upper and lower extremities which were subacute in onset and developed over 10 days. No past medical history of infections, rheumatic fever, or family history of any movement disorder was noted. Physical examination suggested choreoathetoid movements in the left upper and lower extremities. Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal range except hemoglobin was 8.2 g/dl. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain [Figure 1] showed loss of normal flow void signal in the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) with multiple flow voids in the region of lenticulostriate branches. Diffusion-weighted imaging did not reveal abnormal restricted diffusion ruling out an acute basal ganglia stroke. She was started on aspirin and tetrabenazine for chorea. Since her symptoms persisted, a multislice, multiplanar computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the circle of Willis [Figure 2] was done, suggesting mild narrowing of petrous, cavernous, and supraclinoid segments of the right internal carotid artery (ICA). The M1 and M2 segments of the right MCA were thin in caliber with paucity of its distal branches, and multiple collaterals were noted in the lenticulostriate region suggestive of moyamoya vessels. Other medical conditions associated with MMS such as vasculitis, autoimmune conditions, infections, thrombophilias, and connective tissue disorders were ruled out on history, physical examination, and relevant blood investigations. PRBC transfusions were reinitiated and aspirin was continued. She has continued to remain asymptomatic without neurological deficits. After 5 months, follow-up 3.0-Tesla MR angiography of cerebral vasculature using a three-dimensional time-of-fight sequence [Figure 3] showed further narrowing of bilateral anterior cerebral arteries and its branches, namely callosomarginal and pericallosal arteries.

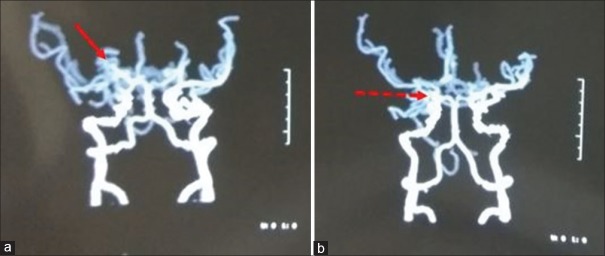

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted axial view showing punctate flow voids in the right basal ganglia and thalamic region (arrow)

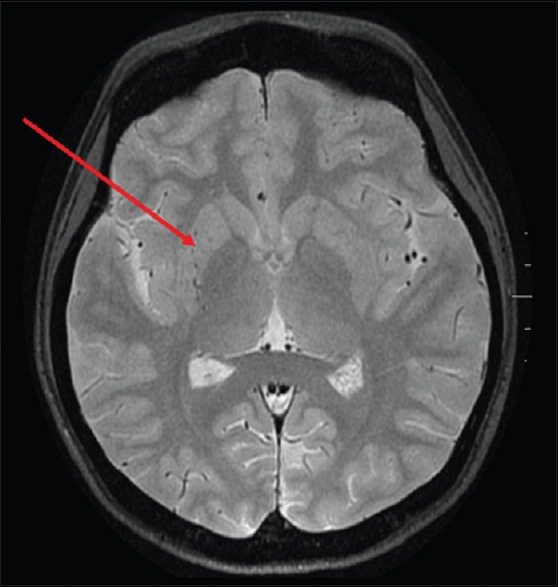

Figure 2.

Computed tomography angiogram of circle of Willis shows. (a) multiple collaterals in the lenticulostriate region (arrow). (b) along with thinning of right MCA and paucity of terminal branches (arrow)

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance angiogram of circle of Willis. (a) axial view showing severe narrowing of the M1 segment of right middle cerebral artery at the origin (arrow). (b) coronal view showing fine collaterals in the region of right basal ganglia and thalamus, arising from anterior choroidal and posterior choroidal arteries (arrow)

Discussion

HbE-beta thalassemia has a wide clinical heterogeneity, ranging from asymptomatic to severe transfusion-dependent thalassemia. MMS presentation is variable and includes transient ischemic attack (TIA), ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and epilepsy although it can rarely develop dystonia, chorea, or dyskinesia.[7,8] Our patient presented with choreoathetoid movements, and other common causes of chreoathetoid movements such as drug side effects, Sydenham's chorea, and neurodegenerative conditions were ruled out by obtaining appropriate medical history, laboratory investigations, and radio imaging. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no cases of MMS or choreoathetoid movements reported with HU therapy in the literature.

In thalassemia, anemia and low hemoglobin levels may cause tissue hypoxia and hypertrophic vascular endothelium, leading to microvascular stenosis.[6,9,10] Hence, regular blood transfusions were re-initiated in our patient. Multiple cerebral infarcts and large arterial occlusions in HbE-beta thalassemia-associated MMS has also been related to its chronic hypercoagulable state. Hypercoagulable state in thalassemia is multifactorial attributed to endothelial activation, altered platelet function, red blood cell membrane abnormalities leading to activation of the coagulation cascades, and changes in coagulation protein levels.[4,9,10]

The diagnosis of MMS is based on the characteristic angiographic appearance of bilateral stenosis affecting the distal ICAs and proximal circle of Willis vessels, along with the presence of prominent basal collateral vessels.[3] Although digital subtract angiography was earlier considered as the gold standard for diagnosis of MMD, MR and CT angiography can noninvasively demonstrate the stenotic or occlusive lesions in distal ICAs and the arteries around the circle of Willis, including the collateral moyamoya vessels in the basal ganglia.[11,12,13] Hence, MR and CT angiography with multirow systems are currently the main imaging methods of diagnostics of the entire range of vascular changes in MMD.[11,12,13] In our patient, CT angiogram of the circle of Willis showed mild narrowing of distal segments of the right ICA, M1, and M2 segments of the right middle cerebral arteries and multiple collaterals in the lenticulostriate region consistent with moyamoya vessels. Follow-up MR angiogram after 5 months showed further narrowing of bilateral anterior cerebral arteries suggesting a progressive disease. In MRI, dilated collateral vessels in the basal ganglia and thalamus can be demonstrated as multiple punctate flow voids, which is considered virtually diagnostic of MMS.[14] MRI in our patient showed loss of normal flow void signal in the right middle cerebral artery with multiple flow void in the region of lenticulostriate branches.

There is no curative treatment for MMS. In patients with MMS, it is important to search for and treat the underlying condition.[3] As our patient did not respond adequately to HU therapy, HU was discontinued, and regular PRBC transfusions were reinitiated as chronic hypoxia due to anemia could have been one of the causative factors for developing MMS. Antiplatelet agents have been used as secondary prevention, particularly in those who are asymptomatic or have mildly symptomatic ischemic disease.[14] Our patient was started on aspirin. Surgical techniques such as direct arterial anastomosis (superficial temporal-to-middle cerebral artery bypass) and indirect synangiosis (encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis) are most often used as secondary prophylaxis for patients with ischemic-type moyamoya who have cognitive decline or progressive symptoms.[3,15] We are also contemplating a surgical intervention such as encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis in our patient.

Conclusion

Choreoathetoid movements or other neurological dysfunctions such as TIA, stroke, or epilepsy in HbE-beta thalassemia could be attributed to MMS, diagnosed preferably by noninvasive angiographic techniques. In MMS, initiation of secondary prophylaxis measures is essential to prevent progression or recurrence of neurological symptoms.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that appropriate patient consent was obtained.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Suzuki J, Kodama N. Moyamoya disease – A review. Stroke. 1983;14:104–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular “moyamoya” disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288–99. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suwanwela NC. Moyamoya disease: Etiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. In: Post TW, editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 May 17]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/moyamoya-disease-etiology-clinical-features-and-diagnosis . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Göksel BK, Ozdogu H, Yildirim T, Oğuzkurt L, Asma S. Beta-thalassemia intermedia associated with moyamoya syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:919–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker TM, Ward LM, Johnston DL, Ventureya E, Klaassen RJ. A case of moyamoya syndrome and hemoglobin E/beta-thalassemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:422–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar KN, Deoghuria D, Sarkar M, Sarkar S. Moya Moya syndrome in a HbE beta thalassemic child presenting with hemiplegia in rural West Bengal. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2016;15:113–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn ES, Scott RM, Robertson RL, Jr, Smith ER. Chorea in the clinical presentation of moyamoya disease: Results of surgical revascularization and a proposed clinicopathological correlation. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;11:313–9. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.PEDS12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baik JS, Lee MS. Movement disorders associated with moyamoya disease: A report of 4 new cases and a review of literatures. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1482–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.23130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharyya M, Kannan M, Chaudhry VP, Mahapatra M, Patil H, Saxena R. Hypercoagulable state in five TI patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2007;13:422–7. doi: 10.1177/1076029607303539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metcalfe SA, Barlow-Stewart K, Campbell J, Emery J. Genetics and blood – Haemoglobinopathies and clotting disorders. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36:812–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarasów E, Kułakowska A, Lukasiewicz A, Kapica-Topczewska K, Korneluk-Sadzyńska A, Brzozowska J, et al. Moyamoya disease: Diagnostic imaging. Pol J Radiol. 2011;76:73–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasuo K, Mihara F, Matsushima T. MRI and MR angiography in moyamoya disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:762–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchiya K, Makita K, Furui S. Moyamoya disease: Diagnosis with three-dimensional CT angiography. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:432–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00593677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roach ES, Golomb MR, Adams R, Biller J, Daniels S, Deveber G, et al. Management of stroke in infants and children: A scientific statement from a Special Writing Group of the American Heart Association Stroke Council and the council On Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Stroke. 2008;39:2644–91. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.189696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baaj AA, Agazzi S, Sayed ZA, Toledo M, Spetzler RF, van Loveren H, et al. Surgical management of moyamoya disease: A review. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E7. doi: 10.3171/2009.01.FOCUS08293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]