Abstract

Bacterial grain rot (BGR), caused by the bacterial pathogen Burkholderia glumae, is one of the most destructive rice (Oryza sativa) diseases in Japan; however, there are no BGR-resistant cultivars for use in Japan. We previously developed a cut-panicle inoculation method to assess the levels of BGR resistance in the World Rice Collection (WRC). Here, we evaluated major Japanese cultivars for BGR resistance and found that none showed “strong” or “medium to strong” resistance; most were categorized as “medium to weak”. On the basis of the screening results, standard cultivars for BGR resistance were selected according to resistance level and relative maturity. Our results indicate that it is necessary to introduce quantitative trait loci (QTLs) from indica or tropical japonica resistant cultivars into Japanese temperate japonica to develop BGR-resistant cultivars for Japan. We previously developed a near-isogenic line (RBG2-NIL) by introducing the genomic region containing RBG2 from ‘Kele’ (indica) into ‘Hitomebore’. In this experiment, we confirmed the resistance level of RBG2-NIL. The resistance score of RBG2-NIL was “medium to strong”, indicating its effectiveness against BGR.

Keywords: Oryza sativa L., disease resistance, bacterial grain rot (BGR), bacterial panicle blight, Burkholderia glumae, cut-panicle inoculation, rice

Introduction

Burkholderia glumae causes bacterial grain rot (BGR) and bacterial seedling rot (BSR) in rice (Oryza sativa L.), which are increasingly important diseases in global rice production (Ham et al. 2011, Mizobuchi et al. 2016). Since B. glumae was first discovered in 1955 in Japan (Goto and Ohata 1956, it has also been reported in other regions such as the USA (Nandakumar et al. 2009), East and South Asia (Ashfaq et al. 2017, Chien and Chang 1987, Cottyn et al. 1996a, 1996b, Jeong et al. 2003, Luo et al. 2007, Mondal et al. 2015, Trung et al. 1993), Latin America (Nandakumar et al. 2007b, Zeigler and Alvarez 1989), and South Africa (Zhou 2014). The term “bacterial panicle blight” is also used to refer to BGR, mainly in the USA and Latin America (Ham et al. 2011). Primary infection occurs when seeds contaminated with B. glumae are sown and then transplanted into fields. At heading, plants located near the diseased primary-infected plants are also attacked by the pathogen, thus establishing secondary infection. The color of the spikelets changes from the normal green to reddish brown, and BGR becomes apparent. Eventually, the infection may cause unfilled or aborted grains (Ham et al. 2011). In 2015, the epidemic area of BGR in Japan covered 30,006 ha (JPPA 2016).

Serious problems are occurring due to BGR and BSR in seed production fields and nursery facilities in Japan (Hasegawa 2012). Seed treatment with oxolinic acid, a quinoline derivative, is a major means of bacterial disease control in Japan (Hikichi 1993a, 1993b, Hikichi et al. 1989). However, the occurrence of BGR strains naturally resistant to oxolinic acid has been a serious limitation to this method (Hikichi et al. 2001, Maeda et al. 2004, 2007). On the other hand, seed disinfection in hot water (for example, 60°C for 10 min) has been established (Hayasaka et al. 2001). Although hot-water immersion was as effective as conventional chemical seed disinfection against damage caused by Pyricularia oryzae (rice blast) (Hayasaka et al. 2001), it was recently found to be somewhat ineffective against diseases caused by B. glumae (Hasegawa 2012).

One reason for the increase in damage by BGR worldwide is climate change. According to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2014, warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia (IPCC 2014). Specifically, the globally averaged combined land and ocean surface temperature data, as calculated using a linear model, show warming of 0.85°C over the period 1880 to 2012 (IPCC 2014). Because the optimal temperature range for the growth of B. glumae is relatively high (30–35°C) (Kurita et al. 1964, Tsushima et al. 1986), global warming may cause BGR to become even more prevalent (Ham et al. 2011).

Many studies have been done to enhance resistance to rice blast, and some blast-resistant cultivars have been developed and cultivated in Japan (Nakamura et al. 2006, Saka et al. 2007). On the other hand, cultivars with BGR resistance have not yet been developed. An urgent necessity for development of BGR resistant cultivars includes the following backgrounds: absence of highly effective pesticide for BGR, sudden outbreak due to environmental changes, and occurrence in both panicle and seedling.

In the past, many field studies have been performed to understand the genetic control of BGR resistance by using spray inoculation at heading or syringe inoculation at booting. Although no source of complete resistance has been discovered (Miyagawa and Kimura 1989, Shahjahan et al. 2000), several cultivars show lower disease severity than others and appear to be partially resistant to BGR (Goto and Watanabe 1975, Groth et al. 2007, Imbe et al. 1986, Mogi and Tsushima 1985, Nandakumar et al. 2007a, Nandakumar and Rush 2008, Pinson et al. 2010, Prabhu and Bedendo 1988, Sayler et al. 2006, Sha et al. 2006, Takita et al. 1988, Wasano and Okuda 1994, Yasunaga et al. 2002). Because BGR tends to be highly affected by environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature, it is difficult to evaluate the resistance of cultivars with different heading dates by using field inoculation (Tsushima 1996).

To minimize environmental variation at the time of inoculation, a “cut-panicle inoculation method” was proposed (Miyagawa and Kimura 1989). This method is based on the “cut-spike” test developed for the evaluation of Fusarium head blight resistance in barley (Hori et al. 2005, Takeda and Heta 1989). This method entails the collection of panicles from field-grown plants and their inoculation under controlled conditions at flowering (Miyagawa and Kimura 1989). By using a revised cut-panicle inoculation method in which panicles at 3 days after heading are harvested and inoculated, we previously assessed the resistance levels of 84 cultivars, including 62 accessions from WRC (the World Rice Collection of NARO), and found 5 to be relatively resistant to BGR (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016). To elucidate the genetic control of the BGR resistance of ‘Kele’, which proved to be the most resistant (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016), we conducted QTL analysis of BGR resistance using backcross inbred lines (BILs) derived from a cross between ‘Kele’ (resistant) and ‘Hitomebore’ (susceptible). We successfully mapped a major BGR-resistance QTL on chromosome 1 and named it RBG2 (Mizobuchi et al. 2015). In 2012 (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016), we examined about 10 temperate japonica cultivars and found none with definite resistance.

Here, we evaluated major Japanese cultivars for BGR resistance to find out whether any resistant Japanese cultivars exist. No Japanese cultivars showed “strong” or “medium to strong” resistance, indicating that it is necessary to introduce QTLs from indica or tropical japonica resistant cultivars into Japanese temperate japonica cultivars to develop BGR-resistant cultivars for use in Japan. To provide a tool for assessment of BGR resistance levels of current and future cultivars, we selected standard cultivars that covered a range of resistance levels and relative maturities.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The names of examined cultivars are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Forty-three major Japanese rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars were grown in paddy fields at NARO in Tsukuba, Japan. Because Hokkaido is a northern area of Japan and the level of damage from BGR is low because of low temperatures, cultivars from Hokkaido were not included in this experiment. Because we have previously assessed WRC cultivars (Ebana et al. 2010, Kojima et al. 2005) for BGR resistance (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016), we included 12 WRC cultivars for comparison. We previously mapped a QTL (RBG2) (Mizobuchi et al. 2015) from ‘Kele’, a resistant traditional lowland indica cultivar that originated in India. We introduced the genomic region containing RBG2 (about 30 kb) into ‘Hitomebore’, a susceptible modern lowland temperate japonica cultivar from Japan, and named the near-isogenic line RBG2-NIL. In this experiment, we analyzed the BGR resistance of RBG2-NIL.

Assessment of panicle resistance to BGR

Fifty-five rice cultivars and RBG2-NIL were grown in paddy fields in 2017. Agricultural chemicals (‘Helseed’ (Hokko Chemical Industry Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) as a fungicide and ‘Stana’ (Sumitomo Chemical Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) as a bactericide) were used for seed disinfection under the guidance of the manufacturers. Twenty-three-day-old seedlings were transplanted at a density of one seedling per hill on 10 May 2017. Each cultivar was planted in a single row of 10 hills at 15 cm between hills and 30 cm between rows. Basal fertilizer was applied at 56 kg N, 56 kg P, and 56 kg K ha−1. Cultivars were categorized by days to heading and inoculated on 17 different dates (experiments 1–17, conducted from 21 July to 11 September). Each inoculation test was confirmed by inclusion of ‘Kele’ (resistant) and ‘Hitomebore’ (susceptible) as controls (Figs. 1, 2). We used the full set of materials (55 cultivars and RBG2-NIL) to analyze the relationships between panicle disease score and daily average temperature at heading or days to heading. Four cultivars from the analysis were deleted from Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 1 because we were not allowed to publicize their names. We expanded the flowering time of ‘Kele’ and ‘Hitomebore’ by transplanting once each week for 10 weeks (from 26 April to 28 June).

Fig. 1.

Difference in resistance to bacterial grain rot (BGR) between (A) Hitomebore and (B) Kele.

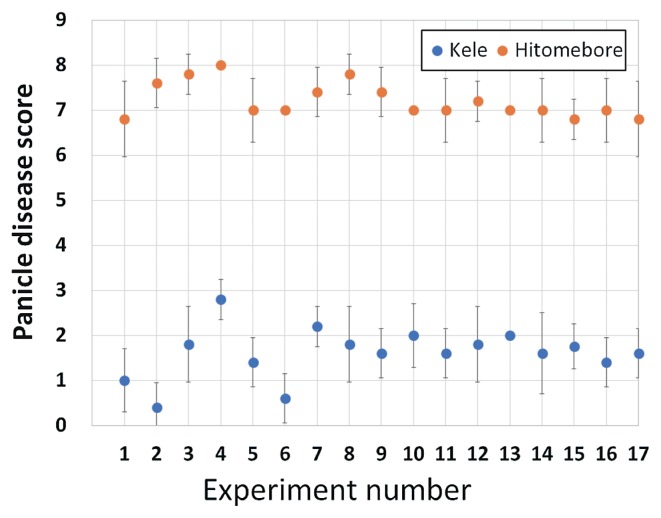

Fig. 2.

Panicle disease scores of control cultivars Hitomebore (susceptible) and Kele (resistant). Error bars indicate SD.

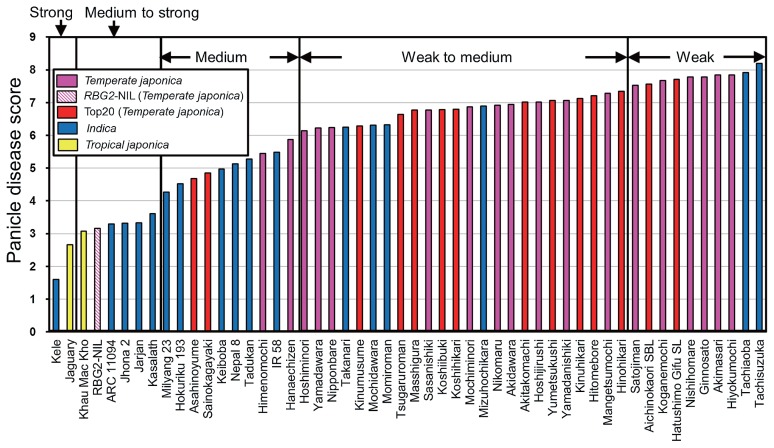

Fig. 3.

Panicle disease scores of cultivars analyzed. Pink bars, temperate japonica; a pink diagonal hatching bar, RBG2-NIL; red bars, “top 20” cultivars (temperate japonica); blue bars, indica; yellow bars, tropical japonica. “Top 20” cultivars are Japanese non-glutinous cultivars (excluding Hokkaido) together representing about 80% of the cultivated rice area in Japan in 2016. Four cultivars from the full analysis were omitted from this figure because we were not allowed to publicize their names.

We measured resistance to BGR in these cultivars by a cut-panicle inoculation method in which panicles at 3 days after heading were harvested and inoculated. Inoculation and measurement were conducted as previously described (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016). Burkholderia glumae strain Kyu82-34-2 (MAFF 302744), which has stable virulence (Tsushima et al. 1986), was used as a source of inoculum. Panicles were spray-inoculated (~1.7–2 ml per panicle) with a freshly prepared inoculum suspension adjusted to OD620 = 0.2 corresponding to 108 cfu per ml. The inoculated panicles were then placed in a plant growth chamber maintained at 27°C and 100% humidity for 20 h. After the infection period, the panicles were covered with a transparent plastic bag and moved to another growth chamber maintained at 27°C according to a 14-h photoperiod with light intensity of 1000 lux. Five panicles per cultivar were inoculated, and disease symptoms were scored 6 days after inoculation on a 0–10 scale, where 0 indicates 0% infected spikelets per panicle (resistant) and 10 indicates >90% infected spikelets per panicle (susceptible). Each cultivar was analyzed three times.

Because cultivars could not all be assessed in the same experiment, revised data were calculated for each cultivar by comparing the scores of ‘Hitomebore’ and ‘Kele’ in each experiment with their average scores and adjusting the scores for the test cultivars accordingly (Supplemental Table 1).

“Daily average temperature at heading stage” of each cultivar was defined as the average of the daily average temperatures of the 4 days from heading to inoculation. We used daily average temperature data for Tsukuba from web page of the Japan Meteorological Agency (http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/indexe.html). To compare the resistance between template japonica and indica, we used the nonparametric Wilcoxon test provided by JMP version 9.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Selection of standard cultivars for BGR resistance

We selected standard cultivars for BGR resistance according to both resistance level and relative maturity. A disease score of <3 was classified as “strong”, a score of ≥3 and <4 as “medium to strong”, a score of ≥4 and <6 as “medium”, a score of ≥6 and <7.5 as “weak to medium”, and a score of ≥7.5 as “weak”.

Results

Assessment of panicle resistance to BGR

We measured the levels of BGR resistance of 55 rice cultivars and RBG2-NIL by the cut-panicle inoculation method. Cultivars were categorized by heading date and inoculated on 17 different dates (experiments 1–17). Each inoculation test was confirmed by inclusion of ‘Kele’ (resistant) and ‘Hitomebore’ (susceptible) as controls. In all experiments, about 6 days after cut-panicle inoculation, many spikelets of ‘Hitomebore’ had brown lesions; in contrast, few spikelets of ‘Kele’ had lesions, and most spikelets had none (Fig. 1). The disease score of ‘Hitomebore’ ranged from 6.8 to 8.0 and that of ‘Kele’ ranged from 0.4 to 2.8 (Fig. 2). The means and standard deviations of BGR of ‘Hitomebore’ and ‘Kele’ were 7.2 ± 0.4 and 1.6 ± 0.6, respectively, and their scores from each individual experiment (1–17) were used to revise the scores of cultivars tested in the same experiment (see Materials and Methods and Supplemental Table 1). The revised panicle disease scores ranged from 1.6 to 8.2 (indica), from 2.7 to 3.1 (tropical japonica), and from 4.7 to 7.8 (temperate japonica), with ‘Kele’ and ‘Tachisuzuka’ being the most resistant and susceptible cultivars, respectively (Fig. 3, Supplemental Table 1). Most of the major Japanese cultivars including ‘Koshihikari’, the leading cultivar in Japan, had scores of 6–7.5 (“weak to medium”), and none showed “strong” or “medium to strong” resistance. ‘Kele’ and ‘Jaguary’ (tropical japonica) showed “strong” resistance, and four indica cultivars (‘ARC 11094’, ‘Jhona 2’, ‘Jarjan’, and ‘Kasalath’) and one tropical japonica cultivar (‘Khau Mac Kho’) showed “medium to strong” resistance. The score (U) by nonparametric Wilcoxon test between template japonica and indica was 285.5, indicating that there is a significant difference (p = 0.0005) between these groups.

These results indicate that it is necessary to introduce QTLs from indica or tropical japonica resistant cultivars into Japanese temperate japonica cultivars to develop BGR-resistant cultivars for use in Japan. The score of RBG2-NIL was 3.2 (“medium to strong”), which was more resistant than any of the temperate japonica cultivars but less resistant than ‘Kele’, the donor cultivar of RBG2. The severity of BGR infection tends to be highly affected by environmental conditions such as temperature (Tsushima 1996). In the cut-panicle inoculation method used in this experiment, temperature was controlled after inoculation. Therefore, we defined the heading stage as the 4 days from heading to inoculation, and analyzed the relationship between panicle disease score and daily average temperature during this period. The daily average temperature at heading for most cultivars ranged from 23.4°C to 26.2°C, but was extremely low (22.1°C) for ‘Tachiaoba’ and ‘Tachisuzuka’ (Supplemental Fig. 1). The heading dates of these cultivars were so late in Tsukuba (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 2) panicle emergence seemed to be incomplete. The disease scores of these two cultivars were very high (≥7.9); thus, the incomplete emergence of panicles probably affected the level of BGR infection.

Selection of standard cultivars for BGR resistance

There was little relationship between panicle disease score and either daily average temperature at heading stage or days to heading. Furthermore, the results for most cultivars obtained in this experiment tended to be similar to those previously obtained by our group (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a). Therefore, the cut-panicle method appears to be a reliable method for evaluating BGR resistance. On the basis of the results from the present study, we selected standard cultivars for BGR resistance according to both resistance level and relative maturity (Table 1). Because both ‘Kele’ and ‘Jaguary’, the only two cultivars found to have strong resistance, belong to the ‘Hitomebore’ maturity class (very early) in Tsukuba, there were no “strong” cultivars in the ‘Koshihikari’ (early), ‘Nipponbare’ (intermediate), or ‘Hinohikari’ (late) classes. To represent the “medium to strong” resistance class, we selected ‘ARC 11094’, ‘Kasalath’, ‘Jhona 2’, and ‘Khau Mac Kho’ for the respective ‘Hitomebore’, ‘Koshihikari’, ‘Nipponbare’, and ‘Hinohikari’ maturity classes. To represent the “medium”, “weak to medium”, and “weak” resistance classes, mainly Japanese standard cultivars were selected. In addition to major cultivars with good eating quality, high-yielding cultivars used mainly for forage or processing were also selected as standard cultivars. As expected, panicle symptoms after inoculation differed among the standard cultivars (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Standard cultivars for BGR resistance, classified according to resistance level and relative maturity

| Relative maturity | Resistance level | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Strong | Medium to strong | Medium | Weak to medium | Weak | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Cultivar name | Scorea | Cultivar name | Scorea | Cultivar name | Scorea | Cultivar name | Scorea | Cultivar name | Scorea | |

| Hitomebore class (very early) | Kele | 1.6 | ARC 11094 | 3.3 | Himenomochi | 5.4 | Akitakomachi | 7.0 | ||

| Jaguary | 2.7 | Hanaechizen | 5.9 | Hitomebore | 7.2 | |||||

| Keiboba | 5.0 | Sasanishiki | 6.8 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Koshihikari class (early) | Kasalath | 3.6 | Nepal 8 | 5.1 | Koshihikari | 6.8 | ||||

| Kinuhikari | 7.1 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Nipponbare class (intermediate) | Jhona 2 | 3.3 | Asahinoyume | 4.7 | Nipponbare | 6.2 | Satojiman | 7.5 | ||

| Tadukan | 5.3 | Mochiminori | 6.9 | |||||||

| Hokuriku 193b | 4.5 | Takanarib | 6.3 | |||||||

| Mochidawarab | 6.3 | |||||||||

| Momiromanb | 6.3 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Hinohikari class (late) | Khau Mac Kho | 3.1 | Hinohikari | 7.3 | Nishihomare | 7.8 | ||||

| Nikomaru | 6.9 | Ginnosato | 7.8 | |||||||

| Yamadanishiki | 7.1 | |||||||||

| Mizuhochikarab | 6.9 | |||||||||

A score of 0 indicates 0% infected spikelets per panicle (resistant); a score of 10 indicates >90% infected spikelets per panicle (susceptible).

Cultivars shown in bold letters are high-yielding cultivars used mainly for forage or processing in Japan.

Discussion

Although BGR caused by B. glumae is one of the most common diseases of the Japanese rice crop, there are no BGR-resistant cultivars adapted for use in Japan. Although there were reports about screening Japanese cultivars that (Mizobuchi et al. 2016), no common cultivars had been scored as resistant. Here, we evaluated major Japanese rice cultivars for BGR resistance and selected a set of standard cultivars for use in future BGR resistance assessments.

Our results clearly indicate that most of the major Japanese cultivars, including ‘Koshihikari’, the leading cultivar in Japan, were scored as “weak to medium”, and none were scored as “strong” or “medium to strong” (Fig. 3). The percentage of planted area represented by the top 20 Japanese non-glutinous cultivars (excluding 3 cultivars from Hokkaido) was about 80% in 2016 (http://www.komenet.jp/pdf/H28sakutuke.pdf), and most of these cultivars showed “weak to medium” resistance (Fig. 3, Supplemental Figs. 1, 2). Similar results were obtained in other studies (Mogi and Tsushima 1985, Takita et al. 1988), in which no highly resistant cultivars or lines of Japan were identified, although resistance levels differed among the materials. Wasano and Okuda (1994) reported that ‘Sasanishiki’ was relatively resistant, but our analysis showed that its score was 6.8 (“weak to medium”). The differences between these two studies could be a result of the different inoculation methods used. Here, we assessed resistance by the cut-panicle inoculation method, whereas Wasano and Okuda performed field evaluation by inoculating a bacterial suspension into the boots (i.e., onto panicles prior to emergence from the stem) with a syringe (Wasano and Okuda 1994). Therefore, it is possible that the influence of environmental conditions after inoculation was lower in our study.

In contrast to the situation with temperate japonica cultivars, some indica or tropical japonica cultivars showed “strong” or “medium to strong” resistance. Thus, it will be necessary to introduce QTLs from indica or tropical japonica resistant cultivars into Japanese temperate japonica to develop BGR-resistant cultivars for use in Japan. We previously finely mapped a QTL (RBG2) from ‘Kele’, a resistant traditional lowland cultivar (indica) that originated in India (Mizobuchi et al. 2015), and developed a near-isogenic line (RBG2-NIL) by introducing the genomic region containing RBG2 into ‘Hitomebore’. The score of RBG2-NIL was 3.2, which is classified as “medium to strong”, although the resistance level was less than that of ‘Kele’. Therefore, we expect RBG2-NIL to become the first BGR-resistant Japanese temperate japonica cultivar in the near future. Besides ‘Kele’, we found several other resistant cultivars. Thus, it is possible that new QTLs from different sources will be detected and utilized for gene pyramiding.

By using cut-panicle inoculation, we could assess disease reactions only 6 days after inoculation; therefore, we are probably measuring the resistance to initial infection. Thus, it will be necessary to confirm the resistance of RBG2-NIL to BGR just before harvest, for which we are planning to conduct field evaluation.

We confirmed the resistance of ‘Kele’, ‘Kasalath’, ‘Jhona 2’, ‘Jaguary’, and ‘Khau Mac Kho’, which were also found to be resistant in our previous study (Mizobuchi et al. 2013a, 2016). Two late-flowering cultivars (‘Tachiaoba’ and ‘Tachisuzuka’) were observed to be quite susceptible (Fig. 3). Because the emergence of panicles from the top internode in these two cultivars seemed to be incomplete under low temperature at heading (Supplemental Figs. 1, 2), panicles seemed to be exposed in a suitable environment for BGR infection under high humidity. At least one cultivar scored as “medium to strong” could be identified in each maturity class, but ‘Kele’ and ‘Jaguary’, which showed “strong” resistance, belong to the ‘Hitomebore’ maturity class (very early heading) in Tsukuba, and there was no “strong” cultivar in any of the other maturity classes. When ‘Kele’ and ‘Jaguary’ are used as controls, it is necessary to delay flowering by late transplanting. Because the whole study was conducted in Tsukuba, it is important that the standard cultivars selected by us (Table 1) be evaluated in other areas.

Burkholderia glumae causes not only BGR but also BSR. A previous study found little relationship between resistance to BGR and resistance to BSR among 239 cultivars and 54 breeding lines grown in Japan at that time (Goto 1983). Today, no cultivars of any type have been found to be resistant to both BSR and BGR (Mizobuchi et al. 2016). Therefore, the factors associated with resistance to BSR and BGR seem to be different. To date, only one QTL for resistance to BSR has been identified (Mizobuchi et al. 2013b). This QTL, RBG1 (Resistance to Burkholderia glumae 1; previously named qRBS1), was found on chromosome 10 by analyzing chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) derived from a cross between ‘Nona Bokra’ (BSR-resistant) and ‘Koshihikari’ (BSR-susceptible). Therefore, it will be necessary to combine RBG1, RBG2, and additional QTLs to achieve stable resistance to both diseases.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We thank the large number of researchers at prefectural agricultural institutions and NARO for kindly providing seeds of cultivars used in breeding programs. We are also grateful to Dr. T. Imbe (NARO) for valuable advice. We acknowledge the staff of the technical support section of NARO for field management. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Project for Climate Change, Rice-2006 and Rice-1201) and by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K07264. We thank two editors from ELSS (http://elss.co.jp/en/) for editing our manuscript before submission.

Literature Cited

- Ashfaq, M., Mubashar, U., Haider, M.S., Ali, M., Ali, A. and Sajjad, M. (2017) Grain discoloration: an emerging threat to rice crop in Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 27: 696–707. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, C.C. and Chang, Y.C. (1987) The susceptibility of rice plants at different growth stages and 21 commercial rice varieties to Pseudomonas glumae. J. Agric. Res. China 36: 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cottyn, B., Cerez, M.T., Van Outryve, M.F., Barroga, J., Swings, J. and Mew, T.W. (1996a) Bacterial diseases of rice. I. Pathogenic bacteria associated with sheath rot complex and grain discoloration of rice in the Philippines. Plant Dis. 80: 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Cottyn, B., Van Outryve, M.F., Cerez, M.T., De Cleene, M., Swings, J. and Mew, T.W. (1996b) Bacterial diseases of rice. II. Characterization of pathogenic bacteria associated with sheath rot complex and grain discoloration of rice in the Philippines. Plant Dis. 80: 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- Ebana, K., Yonemaru, J., Fukuoka, S., Iwata, H., Kanamori, H., Namiki, N., Nagasaki, H. and Yano, M. (2010) Genetic structure revealed by a whole-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism survey of diverse accessions of cultivated Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.). Breed. Sci. 60: 390–397. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, K. and Ohata, K. (1956) New bacterial diseases of rice (brown stripe and grain rot). Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 21: 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, T. (1983) Resistance to Burkholderia glumae of lowland rice cultivars and promising lines in Japan. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 49: 410–411. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, T. and Watanabe, B. (1985) Varietal resistance to bacterial grain rot of rice, caused by Pseudomonas glumae. Proc. Assoc. Pl. Prot. Kyushu 21: 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, D.E., Linscombe, S.D. and Sha, X. (2007) Registration of two disease-resistant germplasm lines of rice. J. Plant Regist. 1: 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, J.H., Melanson, R.A. and Rush, M.C. (2011) Burkholderia glumae: next major pathogen of rice? Mol. Plant Pathol. 12: 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, M. (2012) Chemical control of rice plant rot after transplanting caused by Burlholderia glumae. Jpn. J. Phytophatol. 78: 553. [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka, T., Ishiguro, K., Shibutani, K. and Namai, T. (2001) Seed disinfection using hot water immersion to control several seed-borne diseases of rice plants. Jpn. J. Phytophatol. 67: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y., Noda, C. and Shimizu, K. (1989) Oxolic acid. Jpn. Pestic. Infect. 55: 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y. (1993a) Antibacterial activity of oxolinic acid on Pseudomonas glumae. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 59: 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y. (1993b) Relationship between population dynamics of Pseudomonas glumae on rice plants and disease severity of bacterial grain rot of rice. J. Pestic. Sci. 18: 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y., Tsujiguchi, K., Maeda, Y. and Okuno, K. (2001) Development of increased oxolinic acid-resistance in Burkholderia glumae. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 67: 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K., Kobayashi, T., Sato, K. and Takeda, K. (2005) QTL analysis of Fusarium head blight resistance using a high-density linkage map in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 1661–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbe, T., Tsushima, S. and Nishiyama, H. (1986) Varietal resistance of rice to bacterial grain rot and screening method. Proc. Assoc. Pl. Prot. Kyushu 32: 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014, synthesis report, summary for policymakers. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/.

- Jeong, Y., Kim, J., Kim, S., Kang, Y., Nagamatsu, T. and Hwang, I. (2003) Toxoflavin produced by Burkholderia glumae causing rice grain rot is responsible for inducing bacterial wilt in many field crops. Plant Dis. 87: 890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JPPA (2016) Epidemic and controlling areas in 2015. In: Catalogue of agricultural chemicals. Japan Plant Protection Association (eds.), Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, Y., Ebana, K., Fukuoka, S., Nagamine, T. and Kawase, M. (2005) Development of an RFLP-based rice diversity research set of germplasm. Breed. Sci. 55: 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kurita, T., Tabei, H. and Sato, T. (1964) A few studies on factors associated with infection of bacterial grain rot of rice. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 29: 60. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J., Xie, G., Li, B. and Lihui, X. (2007) First report of Burkholderia glumae isolated from symptomless rice seeds in China. Plant Dis. 91: 1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Y., Kiba, A., Ohnishi, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2004) Implications of amino acid substitutions in GyrA at position 83 in terms of oxolinic acid resistance in field isolates of Burkholderia glumae, a causal agent of bacterial seedling rot and grain rot of rice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 5613–5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Y., Kiba, A., Ohnishi, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2007) Amino acid substitutions in GyrA of Burkholderia glumae are implicated in not only oxolinic acid resistance but also fitness on rice plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 1114–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, H. and Kimura, T. (1989) A test of rice varietal resistance to bacterial grain rot by inoculation on cut-spikes at anthesis. Kinki Chugoku Agr. Res. 78: 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi, R., Sato, H., Fukuoka, S., Tanabata, T., Tsushima, S., Imbe, T. and Yano, M. (2013a) Mapping a quantitative trait locus for resistance to bacterial grain rot in rice. Rice 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi, R., Sato, H., Fukuoka, S., Tsushima, S., Imbe, T. and Yano, M. (2013b) Identification of qRBS1, a QTL involved in resistance to bacterial seedling rot in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 2417–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi, R., Sato, H., Fukuoka, S., Tsushima, S. and Yano, M. (2015) Fine mapping of RBG2, a quantitative trait locus for resistance to Burkholderia glumae, on rice chromosome 1. Mol. Breed. 35: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizobuchi, R., Fukuoka, S., Tsushima, S., Yano, M. and Sato, H. (2016) QTLs for resistance to major rice diseases exacerbated by global warming: brown spot, bacterial seedling rot, and bacterial grain rot. Rice 9: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi, S. and Tsushima, S. (1985) Varietal resistance to bacterial grain rot in rice, caused by Pseudomonas glumae. Kyushu Agricultural Research 47: 103. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, K.K., Mani, C. and Verma, G. (2015) Emergence of bacterial panicle blight caused by Burkholderia glumae in North India. Plant Dis. 99: 1268. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, S., Suzuki, K., Ban, Y., Nishikawa, T., Tokunaga, K. and Ohtsubo, K. (2006) Development of a PCR-based marker set for identifying Koshihikari Niigata BLs, near-isogenic lines harboring rice blast resistance genes. Breed. Res. 8: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, R., Bollich, P., Groth, D. and Rush, M.C. (2007a) Confirmation of the partial resistance of Jupiter rice to bacterial panicle blight caused by Burkholderia glumae through reduced disease and yield loss in inoculated field tests. Phytopathology 97: S82–S83. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, R., Rush, M.C. and Correa, F. (2007b) Association of Burkholderia glumae and B. gladioli with panicle blight symptoms on rice in Panama. Plant Dis. 91: 767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, R. and Rush, M.C. (2008) Analysis of gene expression in Jupiter rice showing partial resistance to rice panicle blight caused by Burkholderia glumae. Phytopathology 98: S112. [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar, R., Shahjahan, A.K.M., Yuan, X.L., Dickstein, E.R., Groth, D.E., Clark, C.A., Cartwright, R.D. and Rush, M.C. (2009) Burkholderia glumae and B. gladioli cause bacterial panicle blight in rice in the southern United States. Plant Dis. 93: 896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson, S.R.M., Shahjahan, A.K.M., Rush, M.C. and Groth, D.E. (2010) Bacterial panicle blight resistance QTLs in rice and their association with other disease resistance loci and heading date. Crop Sci. 50: 1287–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, A.S. and Bedendo, I.P. (1988) Glume blight of rice in Brazil: etiology, varietal reaction and loss estimates. Tropical Pest Management 34: 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Saka, N., Terashima, T., Kudo, S., Kato, T., Sugiura, K., Endo, I., Shirota, M., Inoue, M. and Otake, T. (2007) A new high field resistant variety “Mine-haruka” for rice blast. Res. Bull. Aichi Agric. Res. Ctr. 39: 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sayler, R.J., Cartwright, R.D. and Yang, Y. (2006) Genetic characterization and real-time PCR detection of Burkholderia glumae, a newly emerging bacterial pathogen of rice in the United States. Plant Dis. 90: 603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha, X., Linscombe, S.D., Groth, D.E., Bond, J.A., White, L.M., Chu, Q.R., Utomo, H.S. and Dunand, R.T. (2006) Registration of ‘Jupiter’ rice. Crop Sci. 46: 1811–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Shahjahan, A.K.M., Rush, M.C., Groth, D. and Clark, C.A. (2000) Panicle blight. Rice J. 15: 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K. and Heta, H. (1989) Establishing the testing method and a search for the resistant varieties to Fusarium head blight in barley. Japan. J. Breed. 39: 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Takita, T., Imbe, T., Nishiyama, H. and Tsushima, S. (1988) Resistance to rice bacterial grain rot in indica and upland rice. Kyushu Agric. Res. 50: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Trung, H.M., Van, N.V., Vien, N.V., Lam, D.T. and Lien, M. (1993) Occurrence of rice grain rot disease in Vietnam. Int. Rice Res. Notes 18: 30. [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima, S., Mogi, S. and Saito, H. (1986) Effect of temperature on the growth of Pseudomonas glumae and the development of rice bacterial grain rot. Proc. Assoc. Pl. Prot. Kyushu 32: 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima, S. (1996) Epidemiology of bacterial grain rot of rice caused by Pseudomonas glumae. JARQ 30: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wasano, K. and Okuda, S. (1994) Evaluation of resistance of rice cultivars to bacterial grain rot by the syringe inoculation method. Breed. Sci. 44: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga, T., Wada, T., Oosata, K.F. and Hamachi, Y. (2002) Varietal differences in occurrence of bacterial grain rot in rice cultivars with high palatability. Rep. Kyushu Br. Crop Sci. Soc. Japan 68: 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler, R.S. and Alvarez, E. (1989) Grain discoloration of rice caused by Pseudomonas glumae in Latin America. Plant Dis. 73: 368. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.G. (2014) First report of bacterial panicle blight of rice caused by Burkholderia glumae in South Africa. Plant Dis. 98: 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.