Abstract

Introduction

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and its most common polymorphism Val66Met are known to have a role in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) pathogenesis. Evidence is accumulating that there is an involvement of DNA methylation in the regulation of BDNF expression. The aim of this study was to assess in blood samples of MS patients the correlation between the methylation status of the CpG site near BDNF-Val66Met polymorphism and the severity of the disease.

Methods

We recruited 209 MS patients that were genotyped for the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism. For each patient we quantitatively measured the methylation level of cytosine included in the exonic CpG site that can be created or abolished by the Val66Met BDNF polymorphism. Furthermore, we analyzed the clinical history of each patient and determined the time elapsed since the onset of the disease and an EDSS score of 6.0.

Results

The genetic analysis identified 122 (58.4%) subjects carrying the Val/Val genotype, 81 (38.8%) with Val/Met genotype, and 6 (2.8%) carrying the Met/Met genotype. When the endpoint of an EDSS score of 6 was taken into account by means of a survival analysis, 52 failures (i.e., reaching an EDSS score of 6) were reported. When the sample was stratified according to the percentage of the BDNF methylation, subjects falling below the median (median methylation = 81%) were at higher risk of failure (IRD = 0.016; 95%CI = 0.0050–0.0279; p = 0.004).

Conclusions

In patients with a high disease progression the hypomethylation of the BDNF gene could increase the secretion of the protective neurotrophin, so epigenetic modifications could be the organism response to limit a brain functional reserve loss. Our study suggests that the percentage of methylation of the BDNF gene could be used as a prognostic factor for disease progression toward a high disability in MS patient.

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune, inflammatory, demyelinating, neurodegenerative disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) [1,2] in which CD4 and CD8 T-cells and B-cells action leads to a damage of the myelin [3,4]. Numerous scientific studies support the hypothesis of a role of the neurotrophic growth factors in the process of myelin repair [5,6]. As a member of the neurotrophin family, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) has a role in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and in the neuronal differentiation and survival [7–10]. It also helps keeping the integrity of myelin [11,12]. The concentration of serum BDNF in stable relapsing-remitting (RR) MS patients is lower if compared with healthy individuals [13] but a higher one has been detected in patients during MS attacks [14]. Some studies provide evidence for a contribution of the BNDF in the process of remyelination of MS lesions [15]. In the human BDNF gene, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs6265 leads to an amino acid change from valine (Val) to methionine (Met) in position 66 (Val66Met) [16–18]. In MS, this polymorphism has been correlated with cognitive performance and measures of brain atrophy, with ambiguous results [19–21]. Accumulating evidence suggests the involvement of DNA methylation in the regulation of BDNF expression and in the pathology of several neurological diseases [22–25]. To date the methylation level of BDNF has not been investigated in the pathophysiology of MS. The aim of this study is to assess the correlation between the methylation status of CpG site of the BDNF gene and the progression of disability in MS patients.

Methods

Characteristics of the sample

The study sample was composed by 209 subjects (130 women; 62%), with mean age of 45.9 years (standard deviation [DS] = 12.7; median = 45). At the time of observation, 126 (60.3%) of the subjects were affected by RR MS, and 83 (39.7%) were affected by secondary progressive (SP) MS.

The mean duration of follow-up (equivalent to illness duration) was of 13.4 years (SD = 8.2; median = 12 years; maximum = 37 years); mean age at onset was 32.5 years (SD = 11.6; median = 32). Mean Annualized Relapse Rate (ARR) and MRI-ARR were respectively 0.54 (SD = 0.486) and 0.34 (SD = 0.290). The patients were enrolled between 2013 and 2014 and were followed at the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Policlinico “A. Gemelli” in Rome and at the Multiple Sclerosis Unit at the Don Gnocchi Foundation in Milan. The local Ethical committee “Comitato Etico del Policlinico Gemelli” on December 2012 approved the study, and all patients gave their written consent to participate.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using “salting-out” modified method and quantified by the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [26].

High Resolution Melting (HRM) for BDNF rs6265 polymorphism genotyping

We analyzed the BDNF rs6265 polymorphism using HRM technique that characterizes nucleic acid samples based on their disassociation (melting) behavior using StepOnePlus thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The amplification of BDNF rs6265 polymorphism was carried out as previously reported [27]: in brief, the reaction mix (total volume of 20μl), contained 20 nanograms (ng) of genomic DNA, 0.5 μM of either forward/reverse primers and 1X of MeltDoctor HRM Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Thermal cycling consisted of enzyme activation of 10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of each PCR step: (denaturation) 95°C for 15 seconds and (annealing/extension) 60°C for 1 minutes. Finally, melt curve/dissociation: denaturation at 95°C for 10 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 1 minutes, high resolution melting at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing at 60°C for 1 minutes.

DNA melting curves of each samples were analyzed using high resolution melting software 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) to identify homozygous or heterozygous genotypes. Each sample was assessed in triplicate.

Sequencing

The genotypes showing different HRM profiles were sequenced using an ABI310 automatic sequencer and BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Specific primers (BD-SF: 5’-CCTACCCAGGTGTGCGGACC-3’; BD-SR: 5’-GTTTTCTTCATTGGGCCGAAC-3’) were designed to amplify an expected product size of 152 nucleotides and these fragments were bidirectionally sequenced to eliminate sequencing errors. PCR products were purified using SureClean PCR Purification Kit (Bioline, London, UK) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Bisulfite conversion

Bisulfite treatment of DNA converts all unmethylated cytosines to uracil, leaving methylated cytosines unaltered. Genomic DNA (2 μg in 20 μl) was treated with EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After bisulfite conversion, the genomic DNA was quantified by the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA-methylation analysis of rs6265 BDNF by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

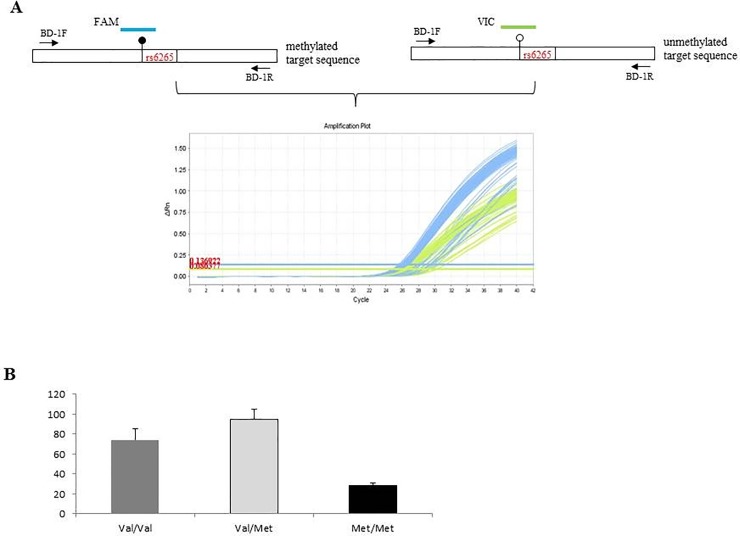

In order to quantitatively measure the methylation level of cytosine included in the exonic CpG site that can be created or abolished by rs6265 BDNF polymorphism, we used bisulfite treatment of DNA and subsequent qRT-PCR. PCR primers are designed to amplify the bisulfite-converted region of 88 bp around BDNF rs6265 polymorphism. The binding sites of these primers lack CpG dinucleotides and, therefore, the nucleotide sequences in methylated and unmethylated DNA are identical after bisulfite treatment. Consequently, it is possible to amplify both alleles in the same reaction tube with one primers pair. Methylation discrimination occurs during probe hybridization by the use of two differently labeled internal TaqMan probes (FAM methyled and VIC unmethyled) (Fig 1A). qPCR was performed using a 96-well optical tray at a final reaction volume of 20 μl. Samples contained 10 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix II, No AmpErase UNG (uracil-N-glycosylase) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), 2 μl of bisulfite-treated DNA, 0.4μM each of the primers BD-1F 5’-GGTTTAAGAGGTTTGATATTATTGGTTGA-3’, BD-1R 5’-CTTCATTAAACCGAACTTTATAATCCTCAT-3’ and 0.2μM each of the fluorescently labeled probes [FAM- 5’ ATACGTGATAGAAGAGTTGTTG 3’(signal methylated), VIC- 5’ ATATGTGATAGAAGAGTTGTTG 3’ (signal unmethylated)] (Fig 1A). Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min to activate the AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase was followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 min (StepOnePlus thermocycler, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primer and probe sequences were selected with the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the guidelines of Wojdacz et al. [28].

Fig 1. BDNF Methylation level determination and results.

A) Up-panel, scheme of human BDNF exonic region that containing rs6265 SNP. The box indicates the coding region, black dot is CpG site with methylation presence and white dot CpG site devoid of methylation. The arrows indicates primers (BD-1F and BD-1R) used in this assay; lower panel, amplification plot representative of the amount of fluorescence dyes FAM (blue) and VIC (green) released during PCR that is directly proportional to the amount of PCR product generated from the methylated or unmethylated allele. B) Average percentage of methylation in MS patients carrying the Val/Val (gray column), Val/Met (light gray column) and Met/Met (black column).

PCR primers were designed to amplify the bisulfite-converted region of 88 bp around BDNF rs6265 polymorphism. The amount of FAM and VIC fluorescence released in each tube was measured as a function of the PCR cycle number at the end of each. The cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a detection threshold is referred to as CT and the difference of both CT values within a sample (ΔCT) is calculated (ΔCT = CTFAM − CTVIC). The percentage of methylation was calculated by taking the threshold cycles determined with each of both dyes:

Signal methylated: CT(CG) (FAM)–represents the threshold cycle of the CG reporter (FAM channel).

Signal unmethylated: CT(TG) (VIC)–represents the threshold cycle of the TG reporter (VIC channel). Percentage of methylation: Cmeth = 100/[1+2(CtCG-CtTG)]% [29,30].

Statistics

Mean comparisons were performed by using t tests with Levene’s test for equality of variance and ANOVA as requested. Frequency comparisons were performed by means of χ2 test with Fischer exact test when required.

The course of the disease was assessed by means of a survival analysis in which the outcome event was defined as the reaching of an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 6 [31]. EDSS is the most used MS disability scale. It ranges between 0.0 (no abnormal neurological signs) to 10 (death for MS). An EDSS score of 6.0 defines the need of assistance for walking and is considered as a marker of unalterable disability progression [32]. The study design was retrospective, thus data about the clinical course of the disease were collected from clinical recordings of the enrolled subjects. Only subjects who were followed-up by the study centers since the onset of the disease were taken into account. The effect of the predictive variables was assessed by determining incidence rates (IRs) and incidence rates differences (IRDs) among groups of exposed and unexposed subjects. IRs were computed by means of person-times analysis, that allows to assess the incidence of the event of interest (outcome) in respect of time of exposition This kind of analysis is useful when retrospective data are taken into account, with different times of observation. Thereafter, a multiple variables Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis was conducted, in which the following variables were entered: age; gender; clinical relapses; MRI relapses; ARR; annualized MRI relapse rate (MRI-ARR); treatment; rs6265 BDNF polymorphism; BDNF methylation; furthermore, given the reported interaction of genotype and methylation [25] an interaction term (polymorphism x methylation) was added to the model. Age, clinical relapses, MRI relapses and treatment were treated as variables changing over time; in other words, the values assumed by each of them was considered for each year of observation. Treatment was stratified as follows: IFN-β1a, IFN-β1b and Glatiramer Acetate were categorized as first line therapies; fingolimod and natalizumab as second line therapies; immunosuppressants (mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine) as third line therapies. Gender, BDNF polymorphism, percentage of methylation of the BDNF gene, ARR and MRI-ARR were treated as variables not changing over time. Finally, in order to allow the comparison among groups of exposed and not exposed subjects, the percentage of BDNF gene methylation was dichotomized splitting the sample in two, between subjects with values of methylation falling above or below the median value.

Results

Methylation analysis of rs6265 BDNF polymorphism

Methylation analysis was focused upon genomic region including one CpG site that can be created or abolished by rs6265 SNP (Fig 1A). Before methylation analysis, we performed genotyping for this polymorphism in our cohort of study using HRM technique [27].

We identified 122 subjects (58.4% of total sample) carrying the Val/Val genotype, 81 subjects (38.8%) with Val/Met genotype, and 6 patients (2.8%) carrying the Met/Met genotype.

Since the group of patients homozygous for the Met allele was very small, we conducted further analysis considering subjects carrying (Met+) or not carrying (Met-) the Met allele.

By qRT-PCR we found that the mean methylation percentage was 80.9 (SD = 16.96; median = 81). Methylation percentage of subjects carrying the Val/Val (mean = 74.58; SD = 10.821), Val/Met (mean = 94.53; SD = 10.722) and Met/Met (mean = 28.50; SD = 2.665) genotypes was significantly different (F2,206 = 160.19; p<0.001) (Fig 1B). These result showed the evidence for an association between rs6265 SNP and DNA methylation in MS patients.

Effect of the rs6265 SNP and BDNF methylation on disease progression: univariate analysis

During the period of interest, 52 failures (i.e., reaching an EDSS score of 6) were reported.

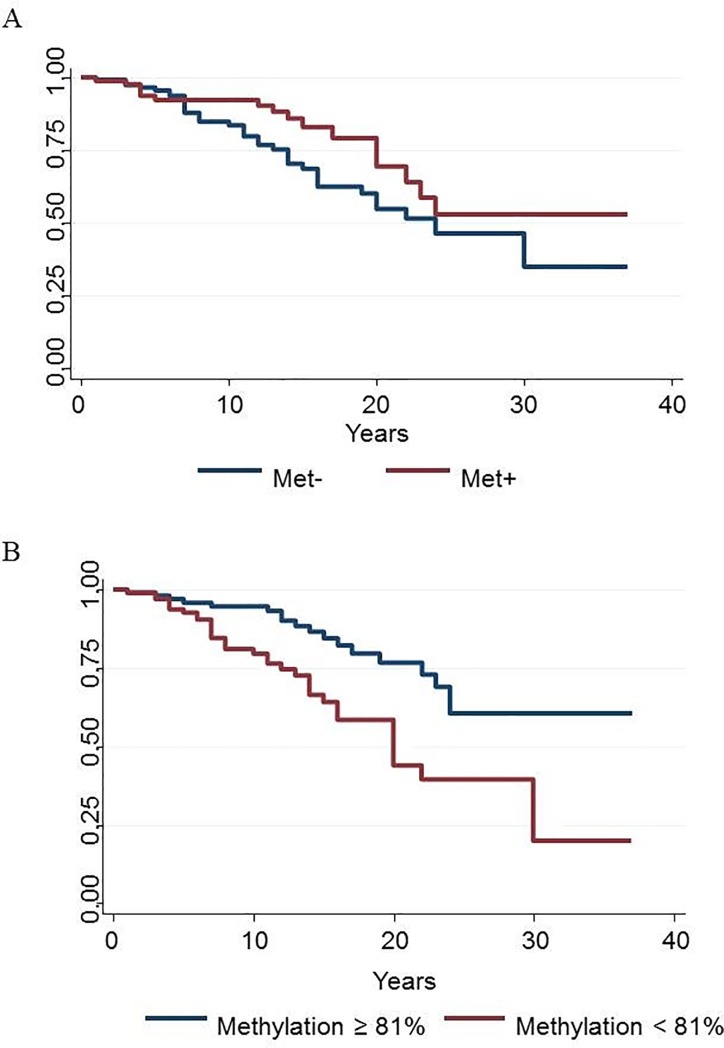

Table 1 reports the incidence rates of the failure. As shown, the failure rate was evenly distributed between the patients carrying or not carrying the Met allele (exposed = Met+; IRD = -0.009; 95% confidence interval [95%CI] = -0.0200–0.0014; p = 0.102). When the sample was stratified according to the percentage of the BDNF methylation, subjects falling below the median (median methylation = 81%) were at higher risk of failure (IRD = 0.016; 95%CI = 0.0050–0.0279; p = 0.004).

Table 1. Incidence rates and incidence rate differences (IRD) of subjects stratified according to BDNF gene polymorphism and BDNF gene methylation.

The exposed are respectively the patients carrying the Met Allele and those presenting a methylation level below 81% while the unexposed are respectively the patients not carrying the Met allele and presenting a methylation level above 81%. 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

| Exposed | Unexposed | IRD | 95%CI | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failures | Time at risk (years) | Incidence rate (event/person/year) | Failures | Time at risk (years) | Incidence rate (event/person/year) | |||||

| BDNF polymorphism | ||||||||||

| Val/Val | 36 | 1496 | 0.024 | |||||||

| Val/Met | 12 | 1005 | 0.012 | |||||||

| Met/Met | 4 | 76 | 0.053 | |||||||

| Met+ | 16 | 1081 | 0.015 | 36 | 1496 | 0.024 | -0.009 | -0.0200 | 0.0014 | 0.102 |

| BDNF gene methylation | ||||||||||

| <81% | 34 | 1165 | 0.029 | 18 | 1412 | 0·013 | 0.016 | 0.0050 | 0.0279 | 0.004 |

Fig 2 displays the survival estimates of the sample stratified according to rs6265 SNP and BDNF percentage of methylation, respectively.

Fig 2. Survival estimates according to rs6265 SNP and BDNF percentage of methylation.

A) survival estimates of subjects carrying (Met+) or not carrying (Met-) the Met allele of the rs6265 SNP. B) survival estimates of subjects with BDNF methylation above or below the median (81%).

Multiple variables Cox’s regression analysis

Table 2 displays the results of the multiple variables regression analysis, in which several demographic (age, gender) and disease-related variables (clinical relapses; MRI relapses; ARR; MRI-ARR; treatment) were entered alongside with rs6265 SNP and BDNF methylation.

Table 2. Results of the multiple variables Cox’s regression analysis.

ARR: annualized relapse rate; ARR-MRI: annualized MRI relapse rate; HR: hazard ratio; SE: standard error; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

| HR | SE | z | p | 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 | 0.017 | 2.30 | 0.022 | 1.006 | 1.073 |

| Gender (F) | 0.56 | 0.200 | -1.62 | 0.105 | 0.277 | 1.128 |

| Clinical relapses | 1.14 | 0.283 | 0.53 | 0.596 | 0.701 | 1.854 |

| ARR | 2.03 | 0.965 | 1.49 | 0.135 | 0.801 | 5.154 |

| MRI relapses | 0.80 | 0.472 | -0.38 | 0.701 | 0.250 | 2.542 |

| ARR-MRI | 0.89 | 0.535 | -0.20 | 0.843 | 0.272 | 2.896 |

| First line treatment | 1.37 | 0.592 | 0.73 | 0.463 | 0.589 | 3.195 |

| Second line treatment | 1.56 | 1.271 | 0.54 | 0.589 | 0.314 | 7.716 |

| Third line treatment | 3.60 | 2.170 | 2.12 | 0.034 | 1.104 | 11.731 |

| BDNF gene polymorphism (Met+) | 0.74 | 0.439 | -0.51 | 0.613 | 0.232 | 2.366 |

| BDNF gene methylation (<81%) | 2.72 | 1.382 | 1.97 | 0.049 | 1.005 | 7.365 |

| Polymorphism X Methylation | 2.36 | 1.890 | 1.07 | 0.283 | 0.491 | 11.339 |

As shown, the occurrence of the failure (EDSS = 6) was predicted by age (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.04; 95%CI = 1.006–1.073; p = 0.022) and by a percentage of methylation below 81% (HR = 2.72; 95%CI = 1.005–11.339; p = 0.049).

Finally, subjects with more aggressive disease, treated with third line agents, were at higher risk of reaching the outcome (HR = 2.17; 95%CI = 1.104–11.731; p = 0.034).

Discussion

Several studies have tried to correlate the role of the most common rs6265 BDNF polymorphism with the prognosis of patients affected by MS, with contradictory data so that other mechanisms are thought to be involved in the modulation of BDNF gene [20,21].

Recent advances in the field of epigenetics, extended the role of epigenetic mechanisms, as methylation, in controlling key biological processes. Our study shows that the rs6265 SNP taken by itself does not link to a different chance of reaching a more severe EDSS score. On the contrary, a lower percentage of methylation of the BDNF gene, regardless of its polymorphism, links to higher odds in reaching an important disability. Considering a higher methylation as a “silencer” of the gene, this result can be translated affirming that a lower inhibition of the gene links to higher odds in reaching an EDSS score of 6.0.

Considering the BDNF as a neurotrophic factor we can assume the percentage of methylation of the BDNF gene as a consequence of the disease activity. Patients with a more severe inflammation could appeal to a de-methylation, hence to a higher secretion of BDNF, in order to preserve the functions of the CNS. The same patients could be the one that, by exploiting at a faster rate the functional reserve of the brain, tend to reach a more severe disability score. On the contrary, patients with a mild or moderate disease activity, could keep the BDNF gene hyper-methylated and tend to maintain a lower EDSS score.

Our study strongly suggests that the BDNF methylation, considered as an epiphenomenon of the disease activity, might help to discriminate patients with a higher inflammatory process from patients with a lower degree of inflammation. If confirmed by further studies, this could become a first reliable prognostic factor in MS potentially helpful for clinicians to distinguish patients with a more severe disease from those with a milder one. Therefore, the use of a such prognostic factor in MS could greatly help the neurologist to identify the patients that could benefit from a more aggressive and earlier therapeutic approach or of an induction strategy as more appropriate treatment.

A better understanding of the BDNF machinery and of its epigenetic regulatory mechanism could impact the management of MS patients facilitating selection of a patient-tailored therapy, thus greatly improving the quality of life of patients and also the comprehension of the disease pathophysiology.

Supporting information

Dataset with the polymorphism and the methylation levels of the BDNF gene for each patient.

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Naegele M, Martin R. The good and the bad of neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;122: 59–87. 10.1016/B978-0-444-52001-2.00003-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold R, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: more pieces of the immunological puzzle. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11: 9–10. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70268-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namaka M, Turcotte D, Leong C, Grossberndt A, Klassen D. Multiple sclerosis: etiology and treatment strategies. Consult Pharm. 2008;23: 886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batoulis H, Addicks K, Kuerten S. Emerging concepts in autoimmune encephalomyelitis beyond the CD4/T(H)1 paradigm. Ann Anat. 2010;192: 179–193. 10.1016/j.aanat.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aharoni R, Arnon R. Linkage between immunomodulation, neuroprotection and neurogenesis. Drug News Perspect. 2009;22: 301–312. 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.6.1395253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acosta CM, Cortes C, MacPhee H, Namaka MP. Exploring the role of nerve growth factor in multiple sclerosis: implications in myelin repair. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12: 1242–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poo MM. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2: 24–32. 10.1038/35049004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4: 299–309. 10.1038/nrn1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24: 677–736. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dincheva I, Glatt CE, Lee FS. Impact of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on cognition: implications for behavioral genetics. Neuroscientist 2012;18: 439–451. 10.1177/1073858411431646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DH, Geyer E, Flach AC, Jung K, Gold R, Flügel A, et al. Central nervous system rather than immune cell-derived BDNF mediates axonal protective effects early in autoimmune demyelination. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123: 247–258. 10.1007/s00401-011-0890-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van't Veer A, Du Y, Fischer TZ, Boetig DR, Wood MR, Dreyfus CF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor effects on oligodendrocyte progenitors of the basal forebrain are mediated through trkB and the MAP kinase pathway. J Neurosci Res. 2009; 87:69–78. 10.1002/jnr.21841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azoulay D, Urshansky N, Karni A. Low and dysregulated BDNF secretion from immune cells of MS patients is related to reduced neuroprotection. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;195: 186–193. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarchielli P, Greco L, Stipa A,Floridi A, Gallai V. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;132: 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makar TK, Bever CT, Singh IS, Royal W, Sahu SN, Sura TP, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene delivery in an animal model of multiple sclerosis using bone marrow stem cells as a vehicle. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210: 40–51. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall D, Dhilla A, Charalambous A, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Sequence variants of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene are strongly associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73: 370–376. 10.1086/377003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112: 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen ZY, Patel PD, Sant G, Meng CX, Teng KK, Hempstead BL, et al. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Met66) alters the intracellular trafficking and activity-dependent secretion of wild-type BDNF in neurosecretory cells and cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24: 4401–4411. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0348-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramasamy DP, Ramanathan M, Cox JL, Antulov R, Weinstock-Guttman B, Bergsland N, et al. Effect of Met66 allele of the BDNF rs6265 SNP on regional gray matter volumes in patients with multiple sclerosis: A voxel-based morphometry study. Pathophysiology. 2011;18: 53–60. 10.1016/j.pathophys.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zivadinov R, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict R, Tamaño-Blanco M, Hussein S, Abdelrahman N, et al. Preservation of gray matter volume in multiple sclerosis patients with the Met allele of the rs6265 (Val66Met) SNP of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16: 2659–2668. 10.1093/hmg/ddm189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liguori M, Fera F, Patitucci A, Manna I, Condino F, Valentino P, et al. A longitudinal observation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA levels in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Brain Res. 2009;1256: 123–128. 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Addario C, Dell’Osso B, Galimberti D, Palazzo MC, Benatti B, Di Francesco A, et al. Epigenetic modulation of BDNF gene in patients with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73: e6–7. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao JS, Keleshian VL, Klein S, Rapoport SI. Epigenetic modifications in frontal cortex from Alzheimer's disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2: e132 10.1038/tp.2012.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82: 696–711. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ursini G, Cavalleri T, Fazio L, Angrisano T, Iacovelli L, Porcelli A, et al. BDNF rs6265 methylation and genotype interact on risk for schizophrenia. Epigenetics. 2016;11: 11–23. 10.1080/15592294.2015.1117736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16: 1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santoro M, Nociti V, De Fino C, Caprara A, Giordano R, Palomba N, et al. Depression in multiple sclerosis: effect of brain derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism and disease perception. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23: 630–640 10.1111/ene.12913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wojdacz TK, Dobrovic A, Hansen LL. Methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(12):1903–8. 10.1038/nprot.2008.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, et al. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28: E32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cottrell S, Jung K, Kristiansen G, Eltze E, Semjonow A, Ittmann M, et al. Discovery and validation of 3 novel DNA methylation markers of prostate cancer prognosis. J Urol. 2007. May;177:1753–1758. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33: 1444–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomassini V, Fanelli F, Prosperini L, Cerqua R, Cavalla P, Pozzilli C. Predicting the profile of increasing disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;2: 1352458518790397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dataset with the polymorphism and the methylation levels of the BDNF gene for each patient.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.