Abstract

Increasing demand for timely and accurate environmental pollution monitoring and control requires new sensing techniques with outstanding performance, i.e., high sensitivity, high selectivity, and reliability. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), also known as porous coordination polymers, are a fascinating class of highly ordered crystalline coordination polymers formed by the coordination of metal ions/clusters and organic bridging linkers/ligands.

Owing to their unique structures and properties, i.e., high surface area, tailorable pore size, high density of active sites, and high catalytic activity, various MOF-based sensing platforms have been reported for environmental contaminant detection including anions, heavy metal ions, organic compounds, and gases. In this review, recent progress in MOF-based environmental sensors is introduced with a focus on optical, electrochemical, and field-effect transistor sensors. The sensors have shown unique and promising performance in water and gas contaminant sensing. Moreover, by incorporation with other functional materials, MOF-based composites can greatly improve the sensor performance. The current limitations and future directions of MOF-based sensors are also discussed.

Keywords: Metal–organic frameworks, Environmental contaminant, Optical sensor, Electrochemical sensor, Field-effect transistor sensor, Micro- and nanostructure

Highlights

Representative metal–organic framework (MOF)-based sensing platforms in environmental contaminant detection are introduced.

The unique structures and properties of MOFs lead to high sensing capabilities in environmental contaminant detection.

By combining with functional materials, MOF-based composites can improve sensor performance.

Introduction

In the past decades, with the population boom and industry development, environmental pollution has become a serious problem for the ecosystem and public health. Many types of pollutants, e.g., water and air pollution of heavy metals, organic compounds, and toxic gases, are associated with health risks [1]. Chromatography and its coupled techniques are the most widely used methods in determining environmental contaminants [2, 3]. However, chromatography-based techniques often require expensive equipment, complex pretreatment, and long test times. Thus, new sensing technologies, which posses the advantages of high sensitivity, rapid detection, ease of use, and suitability for in situ, real-time, and continuous monitoring of environmental pollutants, are highly needed.

A sensor is normally composed of a sensing unit and a transduction unit to translate the sensed information into another type of signal, e.g., an electrical or optical signal. The working principle of a sensor is based on its transduction mechanism, which is based on changes in the optical, electrical, photophysical, or mechanical properties of the sensing element in the sensor when it interacts with the analytes [4–6]. In a sensor, important sensing characteristics include sensitivity, selectivity, response time, reusability, long-term stability, and cost [7]. Hence, the selection and design of the sensing material employed in the sensor platform are key points with regard to sensor performance. To date, various micro- and nanomaterials with different characteristics have been employed in environmental monitoring sensors [8], including nanocarbon materials (carbon nanotube and graphene) [9–13], metals and metal oxides [14–16], semiconducting materials [17, 18], quantum dots [19, 20], and polymers [21, 22]. The development of novel sensing materials with excellent properties greatly promotes sensor research and applications.

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), also known as porous coordination polymers (PCPs), are a fascinating class of highly ordered crystalline coordination polymers formed by the coordination of metal ions/clusters and organic bridging linkers/ligands [23], which combine the intrinsic merits of the rigid inorganic materials and flexible organic materials. The coordination of metal ions/clusters and ligands results in the formation of extended infinite networks. The concept of MOF was first studied by the Yaghi group in 1995 [24]. They reported a classic MOF structure (MOF-5 based on Zn) with a large specific surface area of 2900 m2 g−1 and a porosity of 60% in 1999 [25]. Subsequently, many types of MOFs were reported with designed structural, magnetic, electrical, optical, and catalytic properties by choosing appropriate metal ions and organic ligands [26]. Given the wide choices of metal and ligand combinations, MOFs thrive on structural diversity and tunable chemical and physical properties. Owing to their unique structures, MOFs can have an ultrahigh Langmuir surface area (> 10,000 m2 g−1) [27], which is several times higher than that of activated carbon (1200 m2 g−1). In addition, the tunable pores and high porosity of MOFs enable their applications in gas storage and separation [28, 29], drug delivery [30, 31], chemical separation [32], sensing [33–35], catalysis [36–38], and bio-imaging [39, 40].

The reversible adsorption, high catalytic activity, tunable chemical functionalization, and diverse structure of MOFs make them ideal sensing elements in chemical sensors [41]. The chemical, physical, and structural changes in an MOF upon adsorption of guest molecules have been utilized in recent years for the detection of environmental contaminants including heavy metals, organic compounds, and toxic gases [42]. This review will introduce recent advances in MOFs-based sensors for the detection of environmental contaminants. Specifically, we will focus on the use of MOF-based materials in optical, electrochemical, and field-effect transistor (FET) sensors. The typical structures and working principles of these sensors will be discussed. Representative examples of these sensors will be introduced, and the critical features and advantages of MOFs that are desired for the sensing performance are highlighted. A summary of current limitations and challenges of MOF-based sensors, and an outlook of the future direction of this emerging sensing material, will also be given.

MOF-Based Sensors in Aqueous Solution

Water pollutants including heavy metals, anions, organics, antibiotics, and bacteria are harmful to human health and the ecological environment. Therefore, sensitive and reliable sensors for the determination of water contamination are of great significance. MOFs have been widely utilized for chemical detection in an aqueous solution owing to their unique characters for selective capture and determination of analytes. Their porosity and large surface area enable the reversible adsorption and release of target molecules. MOF-based sensors have been used in various sensors relying on luminescent, electrochemical, and colorimetric signals. Although the sensors are based on different sensing mechanisms, the sensing performances of the sensors are promising in water pollutant detection.

Luminescence Sensors

A considerable amount of work using MOFs as sensing elements for chemical sensors in aqueous solution was based on the luminescence property of MOFs [1, 43]. Luminescence occurs when electrons in excited singlet states return to the ground state via photon emission [44]. This leads to the luminescence phenomenon of the MOF, which is attenuated or quenched upon the absorption of analyte and is known as the “turn-off” mechanism [45]. By contrast, there are also reports in the literature that focus on luminescence enhancement, described as a “turn-on” mechanism [46]. The quantitative and qualitative analysis of analytes can be determined through the luminescence enhancement, quenching, or the movement of the emission wavelength. MOF-based materials are promising as multifunctional luminescent materials since both organic and inorganic components can provide a platform to generate a luminescence signal. The metal–ligand charge transfer-based luminescence within MOFs can bring other dimensional luminescent functionalities; moreover, some guest molecules incorporated in MOFs can emit or induce luminescence [44, 47–52].

Inorganic Anion Sensing

Nutrients such as phosphate ions (PO43−) in water lead to eutrophication and result in the reduction or elimination of dissolved oxygen, resulting in a negative effect on the water ecosystem [53]. Various luminescent MOF sensors have been employed for the selective detection of nutrient ions. Qian et al. [54] reported on a highly selective photoluminescence quenching-based PO43− sensor with the C3v symmetric cavity of a Tb(III)-based MOF compounds, TbNTA1 (NTA = nitrilotriacetate). This study revealed that inorganic ions including F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, NO3−, NO2−, HCO3−, CO32−, and SO42− have no impact on the fluorescence intensity of TbNTA1, and only PO43−-incorporated TbNTA1 led to a tremendous luminescence quenching effect. The quenching effect can be explained by the matching degree of TbNTA1 with anions. PO43− anions have a tetrahedral shape, and after being incorporated with TbNTA1, the Tb–O bond may weaken the energy that is transferred to Tb3+ via nonradioactive relaxation, inducing the luminescence quenching effect. The matching degree of TbNTA1 with PO43− anions is determined by the anion size and pH value. This work was the first report of MOF sensors for highly selective sensing of PO43− anions in aqueous solution.

The Lu group developed an effective fluorescent sensing platform for phosphate detection based on MOF and ZnO quantum dot (QD) conjugates [55]. The MOF material (MOF-5) was used as the substrate, and positively charged ZnO QDs capped by (3-aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane (APTMS–ZnO QDs) were attached to the negatively charged MOFs via amine–Zn interaction and electrostatic interaction. This interaction resulted in the ZnO QD fluorescence quenching owing to the electron transfer process. After introducing phosphate into the QD–MOF system, the presence of phosphate could inhibit the quenching effect and recover the fluorescence of ZnO QDs. The fluorescence intensity depended on the phosphate concentration and was not affected by other interfering species. This fluorescent sensing platform had good sensitivity with a linear working range of 0.5–12 μM and a detection limit of 53 nM. In this study, the sensing platform also shows a satisfactory sensing performance with real water samples. However, such luminescence-functionalized MOF (LMOF) sensors are not reusable.

The first report on reusable MOF-based phosphate sensors was recently presented. In this report, a water-stable 3D-MOF Eu-BTB (based on H3BTB = 1,3,5-benzenetribenzoate) was exploited for gleaning an excellent phosphate-selective sensing performance [56]. The luminescence intensity of MOF compounds remained unchanged even after five runs of testing, indicating that interaction between the Eu-BTBn and PO43− is weak and the luminescence recovery may be owing to the removal of PO43−.

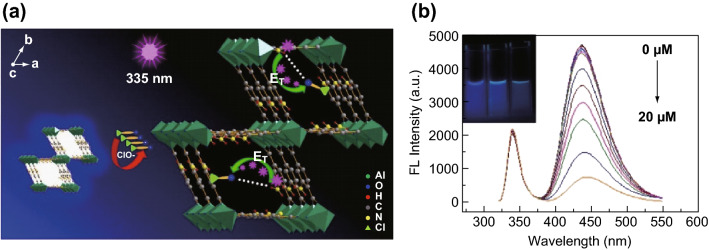

It is of great importance to monitor and control the free ClO− ions in drinking water because low-level free ClO− ions cannot kill viruses or pathogenic bacteria effectively, while a higher level may produce many disinfect byproducts (DBPs), which are harmful to human health. Recently, Lu and coworkers proposed a novel fluorescent sensing platform to detect free chlorine based on MOF hybrid materials [57]. The NH2-MIL-53(Al) was synthesized by a facile one-step hydrothermal treatment of AlCl3·6H2O and NH2-H2BDC in water with urea as a modulator. The as-synthesized Al nanoplates exhibited excellent water solubility and stability. The strong fluorescence of Al nanoplates was significantly suppressed after the addition of free chlorine (Fig. 1a). The sensor platform had a good detection limit of 0.04 μM and a wide detection range from 0.05 to 15 μM (Fig. 1b). The mechanism study suggested that the energy transfer through N–H···O–Cl hydrogen bonding interactions between the amino group and ClO− ions plays a key role in fluorescence suppression. Recovery tests with real tap water and swimming pool water samples showed that the recoveries for real water sample determination were 97–101%.

Fig. 1.

a Working principle of NH2-MIL-53-based sensor for ClO− sensing. b Fluorescence emission spectra of NH2-MIL-53(Al)-based sensor toward various concentrations of ClO−: 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 0.8, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 15, and 20 μM from top to bottom. Inset shows corresponding photographs of NH2-MIL-53(Al) nanoplates in the absence (left) and presence of 10 μM (middle) and 20 μM (right) ClO− under 365 nm UV light.

Reprinted with permission from [57]. Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society

In addition to the abovementioned inorganic anions, the cyanide ion (CN−) is another important contaminant in water, as it is one of the most toxic and lethal pollutants presently occurring in nature. The Ghosh group reported on a selective and sensitive fluorescent senor for the aqueous-phase detection of CN− using an MOF-based system [58]. In this study, a post-synthetic modification of ZIF-90 with the specific recognition sites for CN− was applied. This could selectively sense CN− at 2 μM and fulfilled the permitted contamination limit of 2 mM in drinking water set by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Heavy Metal Ion Sensing

Heavy metal ions are one of the nonbiodegradable pollutants in the water environment. Some heavy metals ions including copper (Cu), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), and cadmium (Cd) are considered to be highly toxic and hazardous to human health even at a trace level. Therefore, many MOF-based sensors have been reported for heavy metal ions detection in water. Lin et al. [59] reported on a highly sensitive and selective fluorescent MOF-based probe for copper ion (Cu2+) detection. The branched poly (ethylenimine)-capped CQDs (BPEI-CQDs) with strong fluorescent activity (quantum yield > 40%) and excellent selectivity for sensing Cu2+ ions was encapsulated into a zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8). The obtained BPEI-CQDs/ZIF-8 composites have been used for ultrasensitive and highly selective copper ion sensing. ZIF-8 not only exhibits excellent fluorescent activity and selectivity derived from CQDs but can also accumulate Cu2+ owing to the high adsorption property. The accumulation effect of MOFs can amplify the sensing signal. The fluorescent intensity of BPEI-CQDs/ZIF-8 was quenched with the presence of Cu2+. This sensing platform can detect Cu2+ in a wide concentration range of 2–1000 nM and a lower limit of detection (LOD) of 80 pM. Compared with other fluorescent sensors without the amplifying function of MOF or the introduction of a guest luminophore, this sensing platform has a much lower detection limit of approximately two orders of magnitude. This sensor was also applied in real water sample tests and showed good performance. This study indicated that novel sensing platforms can be designed and applied in heavy metal ion detection by incorporating MOFs with fluorescent nanostructures.

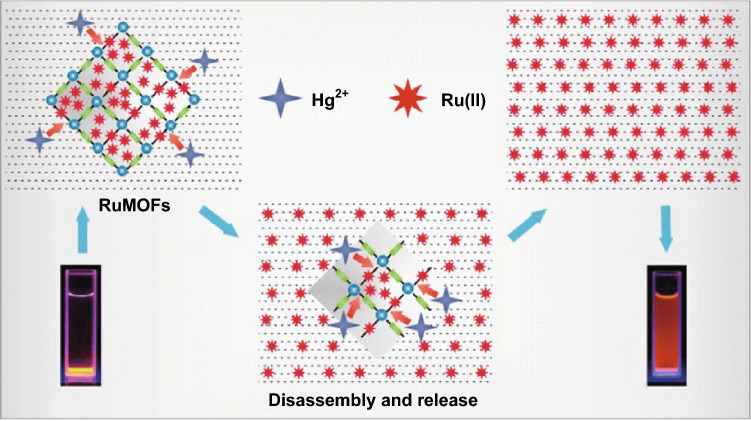

Mercury ion (Hg2+) detection is of special importance given that these substances have high toxicity and present risks to human health. A rapid and selective sensing strategy for detection of Hg2+ based on Ru-MOFs was developed by the Chi group [60]. As shown in Fig. 2, the luminescent Ru(bpy)32+ was doped in an Ru-MOF framework and encapsulated in the pores of MOF. Before interaction with Hg2+, the Ru-MOFs were precipitant in water (yellow powder) and emitted a red color under UV light. However, in the presence of Hg2+, the Ru-MOFs were rapidly decomposed by Hg2+ ions and released large amounts of luminescent guest materials into the water, i.e., Ru(bpy)32+, giving rise to strong fluorescence or electrochemiluminescence signals. As the Ru(bpy)32+ was released, the water solution turned yellow and showed red light emission under UV light. The sensor works well when the concentration of Hg2+ is in the range of 25 pM to 50 nM with an LOD of 8.2 pM. The LOD was much lower than the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) mandate of 2 ppb (10 nM) for Hg(II).

Fig. 2.

Sensing mechanism of Hg2+-responsive disassembly of Ru-MOFs and release of guest material of Ru(bpy)2+3.

Reprinted with permission from [60]. Copyright (2015) American Chemical Society

Chen et al. [61] designed a turn-on fluorescent sensor based on lanthanide MOF nanoparticles. This sensor can detect Hg2+ through an inner-filter effect. Fluorescent Eu-isophthalate MOF nanoparticles were synthesized with an average diameter of 400 nm and exposed to imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylic acid (IDA). The IDA could coordinate with the MOF particle and quench the MOF emission owing to imidazole’s strong absorbance in the MOF excitation region. However, upon Hg2+ addition, Hg2+ strongly coordinated with IDA and released IDA molecules from the MOF surface, thus restoring the emission. This sensing interaction was both sensitive and selective, with an LOD of 2 nM and negligible responses to Ag+, K+, Na+, Mg2+, and Pb2+.

Organic Compound Sensing

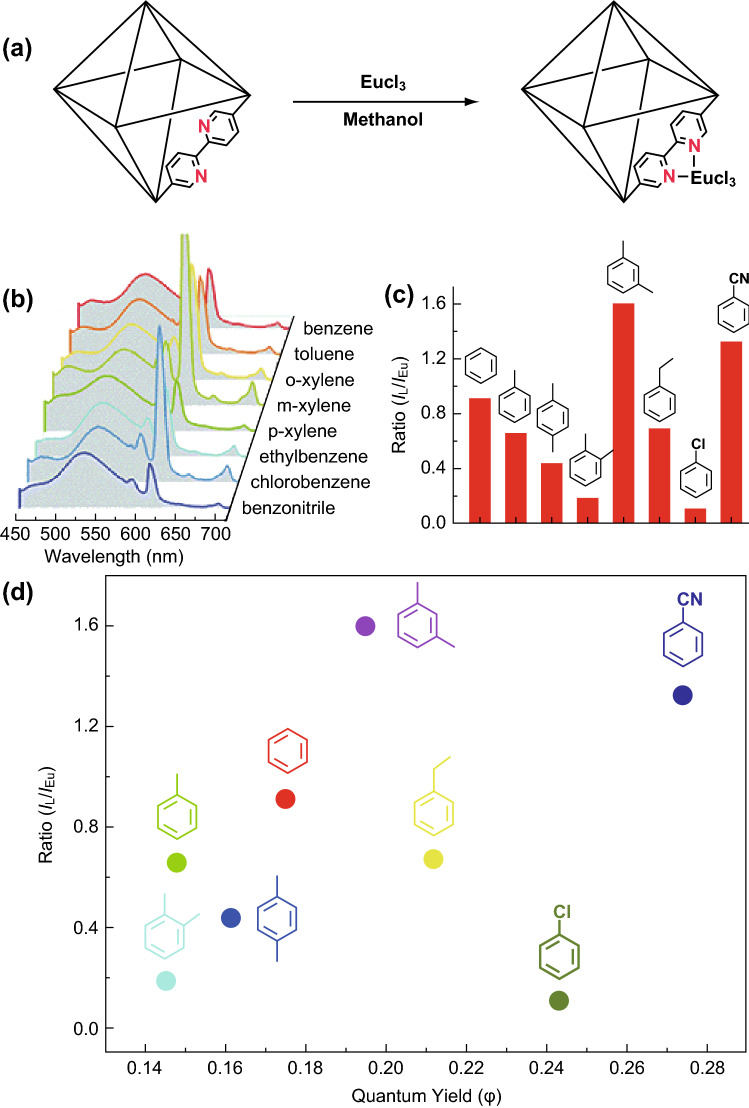

Among water pollutants, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as benzene and its derivative aromatic compounds are substantively toxic pollutants that can cause severe environmental problems and pose threats to the ecosystem [62]. Recently, a fluorescent MOF was established by incorporation of Eu3+ cations into a nanocrystalline MOF Zr6(u3–O)4(OH)4(bpy)12 (recognized as bpy-UiO, bpy = 2,2-bipyridine-5,5-dicarboxylic acid), which could detect aromatic VOCs with high performance [63]. As shown in Fig. 3, the sensor works with an unprecedented dual-readout orthogonal identification scheme. In this sensor, the MOF and VOCs binding event could be recognized with two-dimensional (2D) readouts that combined the intensity ratio of the ligand-based emission to the Eu3+ emission (IL/IEu) and luminescence quantum yield. Since the fluorescence characteristics of the MOF nanocomposite rely heavily on the VOCs properties, the retrievable identities of VOCs can be succinctly decoded into an analogous 2D readout (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

a Post-synthetic modification of UiO-bpy with Eu3+. b Emission profiles and c bar diagram depicting relative intensity ratios (IL/IEu), after addition of VOCs. d Two-dimensional map displaying relative emission intensities and quantum yields of various VOC encapsulated phases.

Reprinted with permission from [63]. Copyright (2016) Royal Society of Chemistry

Morsali et al. [64] explored novel sensing probes for the detection of nitroaromatic compounds based on TMU-31 and TMU-32 MOFs. These two MOFs were mixed with nitro-substituted compounds for sensing. In the fluorescence emission spectra, the quenching efficiency of TMU-31 and TMU-32 for nitroaromatic compounds is shown as follows: 1,3-dinitrobenzene (1,3-DNB) > 2,4-dinitrotoluene (2,4-DNT) > nitrobenzene (NB) > nitromethane (NM) > 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT). This study revealed that the urea groups inside the pore cavity of MOFs work as binding sites for nitroanalytes through N–H···O hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking interactions. In addition, it was found that the urea group’s orientation inside the pore cavity of MOFs and the supramolecular interactions between the interpenetrated networks are important to nitro-substituted compound sensing.

Zhang et al. reported on an electrochemically synthesized IRMOF-3, which was synthesized by an electrochemical strategy at room temperature for the first time. The electrochemical system consisted of a zinc plate as the anode, a copper plate as the cathode, tetrabutylammonium bromide (TATB) as supporting electrolyte, and DMF–ethanol as solvent. The system exhibited high fluorescent detection properties for 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP) with a detection limit up to 0.1 ppm [65].

Antibiotic tetracycline (TC) is one of main organic contaminates in water and is difficult to degrade in water. The Cuan group developed a dual-functional platform for the detection and removal of TC with a highly stable luminescent zirconium-based MOF (PCN-128Y) [66]. The detection was based on the efficient luminescence quenching of PCN-128Y toward TC. Theoretical and experimental studies revealed that the luminescence quenching can be attributed to a combined effect of the strong absorption of TC at the excitation wavelength and the photo-induced electron transfer process from the ligand of PCN-128Y to TC. The strong metal–ligand bonding between Zr6 nodes and TC through solvent-assisted ligand incorporation was suggested to mainly account for the high adsorption capability of PCN-128Y toward TC in water. The preconcentration of TC within the pores of PCN-128Y induced by the adsorption process significantly enhanced the efficiency of TC sensing.

Electrochemical Sensors

An electrochemical sensor works based on the redox reactions of the analytes in an electrochemical system. The electrochemical measurement is normally carried out using a three-electrode system consisting of a working electrode, a counter electrode, and a reference electrode. The amount of analytes involved in the reaction can be determined by measuring the current, electric potential, or other electrical signals [67, 68]. MOFs show potential as electrochemical sensing surface modifiers because of their high surface area and pore volume, good absorbability, and high catalytic activity [69, 70]. With the rapid development of synthesis methods, stable MOFs with high electrical conductivity have been successfully designed and synthesized [71–73]. However, most MOFs still have poor electrical conductivity and relatively low stability in aqueous solution; this is a result of the reversible nature of the coordination bonds. In addition, MOFs usually have a micron size, resulting in limited adhesion affinity between MOFs and the electrode surface. These disadvantages of MOFs limit their applications in electrochemical sensors. The key to achieving efficient electrochemical signals is to prepare MOFs with high redox activity and electrical conductivity while preserving their unique pore structure. One of the commonly applied methods to resolve these problems is combining MOFs with other functional materials that have high electrical conductivity [33, 74, 75].

Ion Sensing

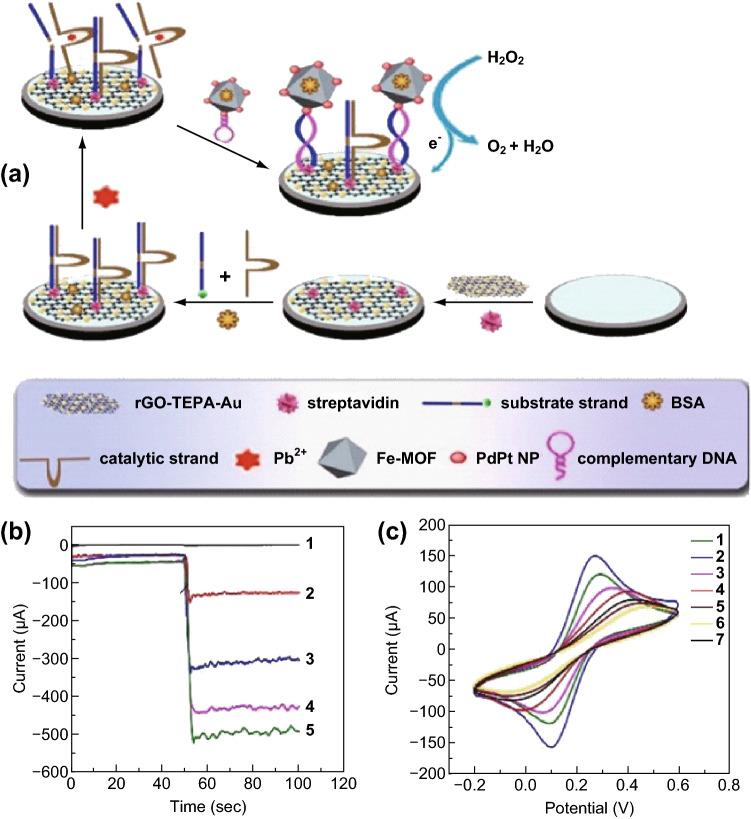

Lead ion (Pb2+) is one of the most toxic and commonly found heavy metal ions in aquatic ecosystems. The monitoring of Pb2+, especially trace amounts of Pb2+ in the water environment, is important to the public health. Recently, the He group designed a detection strategy to detect Pb2+ using Pd–Pt alloy-modified Fe-MOFs (Fe-MOFs/PdPt NPs) with hairpin DNA immobilized on the surface as a signal tag [76]. As shown in Fig. 4, a streptavidin-modified reduced graphene oxide-tetraethylene pentamine-gold nanoparticle (rGO-TEPA-Au) composite serves as the sensor platform for DNAzyme immobilization. In the presence of Pb2+, the substrate strand of the DNAzyme is catalytically cleaved, resulting in the detachment of the catalytic strand from the sensor. The newly generated single-strand DNA on the sensor can hybridize with the hairpin DNA. Thus, the hybridized material Fe-MOFs/PdPt NPs is attached to the electrode surface. Fe-MOFs exhibit highly peroxidase activity, and PbPt NPs can enhance the catalysis performance by reducing the H2O2. Based on the sensing strategy, the amount of Pb2+ can be detected by measuring the H2O2 reduction current. This sensor has a linear working range from 0.005 to 1000 nM and an LOD of 2 pM for Pb2+ sensing.

Fig. 4.

a Schematic of sensing strategy. b Amperometric i–t curves of different nanomaterials: (1) Fe-MOFs, (2) Fe-MOFs/AuNPs, (3) Fe-MOFs/PtNPs, (4) Fe-MOFs/PdNPs, and (5) Fe-MOFs/PdPt NPs. c CV characterization of electrodes at various stages of modification: (1) bare GCE, (2) rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE, (3) streptavidin/rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE, (4) substrate strand/streptavidin/rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE, (5) BSA/substrate strand/streptavidin/rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE, (6) catalytic strand/BSA/substrate strand/streptavidin/rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE, and (7) Pb2+/catalytic strand/BSA/substrate strand/streptavidin/rGO-TEPA-Au/GCE.

Reprinted with permission from [76]. Copyright (2018) Elsevier

Another electrochemical sensor based on MOFs for Pb2+ sensing was designed by Guo et al. [77]. Flake-like MOF material NH2-MIL-53(Cr) was prepared using a reflux method and was modified on the surface of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). This sensor showed excellent electronic responses for Pb2+. Under optimal conditions, the oxidation current of Pb2+ linearly increased as the concentration increased in the range of 0.4–80 μM with an LOD of 30.5 nM. The NH2-MIL-53(Cr)-modified electrode also showed excellent selectivity and stability for Pb2+ determination.

Nitrite ion (NO2−) is regarded as an important contaminant in water. The Mobin group designed a hybrid MOF/rGO electrode for the electrocatalytic oxidative determination of nitrite [78]. In this study, Cu-MOFs were stacked with rGO by a simple ultrasonication method. The GCE modified with Cu-MOF/rGO composites exhibited better electrocatalytic performance for nitrite oxidation (LOD of 0.033 mM) than those of an MOF electrode or bare electrode. The improved sensing performance was owing to the increased conductivity of MOF with rGO. Additionally, this sensor showed good selectivity toward nitrite in the presence of common salts such as CH3COONa, KCl, MgSO4, CaCl2, NaClO4, and KNO3. This sensor was also tested with NO2− spiked pond water with recoveries of 100–120%.

Organic Compound Sensing

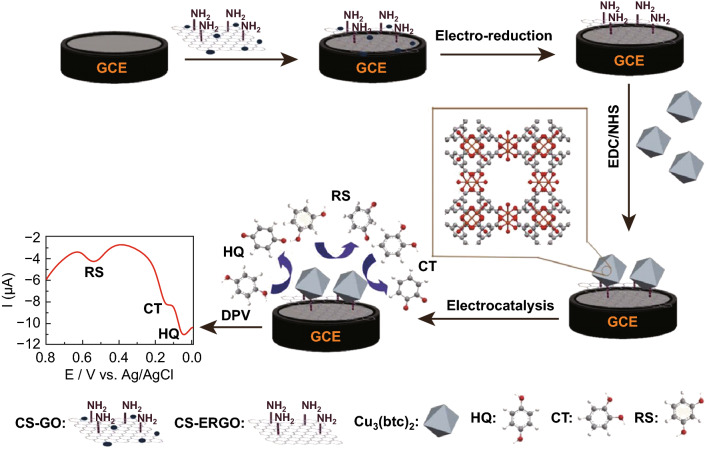

Catechol (CT), resorcinol (RS), and hydroquinone (HQ) are three typical dihydroxybenzene isomers (DBIs) of phenolic compounds, which usually coexist as environmental pollutants [79]. An MOF-based electrochemical sensing platform for the simultaneous detection of these DBIs was developed [80]. As shown in Fig. 5, chitosan (CS) was coated on the electrode surface, along with the doping of GO. Through a simple electroreduction method, the GO in the CS/GO composite was electrochemically reduced to rGO, which had a high electrical conductivity and was utilized as the supporting carrier for the grafting of electroactive MOF Cu3(BTC)2. The good film-forming ability and the covalent binding of GO and CS endowed the sensing surface (Cu3(BTC)2/ERGO/CS) with a high stability. Electrochemical experiments showed that the reduction peaks of RS, CT, and HQ can be well separated from each other, indicating good selectivity. Meanwhile, the high conductivity of the CS/rGO matrix greatly enhanced the current response, leading to good LODs of 0.44, 0.41, and 0.33 μM for HQ, CT, and RS, respectively. The accurate determination of DBIs in real water samples was also realized by the MOF sensor, which broadened the applications of MOFs in organic compound sensing.

Fig. 5.

Schematic and detection strategy of electrochemical sensor based on MOF Cu3(BTC)2 and CS/rGO for DBIs detection.

Reprinted with permission from [80]. Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society

The Wang group designed another electrochemical sensing platform for DBI detection based on MOFs. In this work, magnetic Ni@graphene composites with a core–shell structure (C-SNi@G) were synthesized through the thermal annealing of Ni-BTC MOF [81]. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements showed that only one oxidation peak was found on the bare electrode. This was owing to the overlap of oxidation peaks of HQ and CT, indicating that the HQ and CT could not be differentiated by the bare electrode. However, two distinct oxidation peaks were observed (HQ at 0.085 V and CT at 0.190 V vs. Ag/AgCl, respectively) when the C-SNi@G/MGCE was employed. In addition to the selectivity improvement, the magnetic fabrication of this sensing platform was binder-free and easy to control. The Liu group [82] also reported on a highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for the simultaneous determination of HQ and CT in water based on copper-centered MOF–graphene composites [Cu-MOF-GN, Cu-MOF: Cu3(BTC)2]. Under optimized conditions, the Cu-MOF-GN electrode showed excellent electrocatalytic activity and high selectivity toward HQ and CT. The detection LODs of HQ and CT were 0.59 and 0.33 μM, respectively. The electrode was also applied in spiked tap water with recoveries from 99.0 to 102.9%.

2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP) is one of the chlorinated phenol contaminants in water and can accumulate in the human body through the food chain. It is harmful to human health even at a very low concentration [83]. For the sensitive detection of 2,4-DCP, Dong et al. [84] fabricated a simple and rapid electrochemical sensor employing 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid copper (Cu3(BTC)2) as the sensing material. The fabricated sensors not only exhibited high selectivity toward 2,4-DCP compared with the interferences, but also showed a wide linear sensing range from 0.04 to 1.0 μM and an LOD of 9 nM. The employment of Cu3(BTC)2 presents many advantages such as large specific surface area, high adsorption capacity, and good electron transfer efficiency, which enhance the performance of the electrochemical sensor. Furthermore, the sensor was successfully applied for the determination of 2,4-DCP in reservoir raw water samples with satisfactory results.

Other Sensors in Aqueous Solution

Colorimetric sensors are commonly used in water contaminant sensing based on the chromogenic reaction of colored compounds. The components and amounts of target compounds can be determined by measuring the color change of the solution [85, 86]. The Gu group reported on chromophoric Ru complex-doped MOFs (RuUiO-67) and explored their performance as sensing probes for the colorimetric detection of Hg2+ [87]. It was found that thiocyanate-bearing dyes in Ru(H2bpydc)(bpy)(NCS)2 (H2L) complex could specifically interact with Hg2+ owing to the strong affinity between Hg2+ and the thiocyanate groups in the dyes. Thus, RuUiO-67 served as the recognition site and signal indicator. Upon the addition of Hg2+, a concomitant red-to-yellow color change of the probe suspension was recognized, and the detection limit was determined to be as low as 0.5 μM for Hg2+.

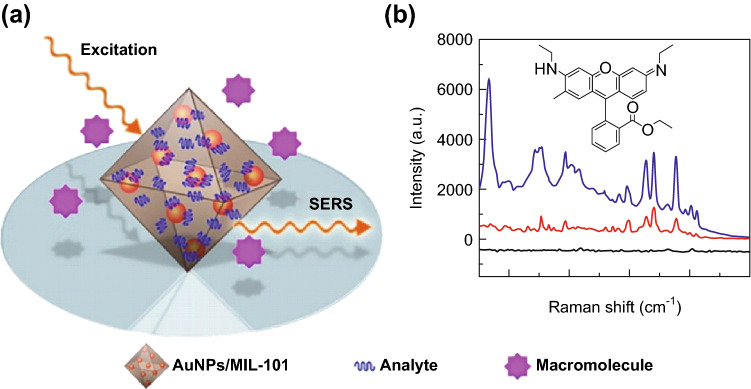

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a promising spectroscopic technique for biological and chemical sensing because of its unique advantages such as high sensitivity with the potential of single molecule detection and highly informative spectra characteristics [88]. The signal of SERS strongly depends on the distance between the analytes and the metal nanostructure. For a quantitative analysis of organic pollutant p-phenylenediamine in environmental water, the Li group [89] utilized an Au NP-embedded MOF structure for SERS detection. In this composite, Au NPs were grown and encapsulated within the host matrix of MIL-101 by a solution impregnation strategy. The Au NP/MIL-101 composites combined the localized surface plasmon resonance properties of Au NP and the high adsorption capability of MOF, making them highly sensitive SERS substrates by the effective preconcentration of analytes in close proximity to the electromagnetic fields at the SERS-active metal surface (Fig. 6a). The SERS substrate was sensitive and robust to several different target analytes (Fig. 6b). The substrate also showed high stability and reproducibility owing to the protective shell of the MOF. The practical application potential of the SERS substrate was evaluated by a quantitative analysis of organic pollutant p-phenylenediamine in environmental water and tumor marker alpha-fetoprotein in human serum. The sensor showed good linearity between 1 and 100 ng mL−1 for p-phenylenediamine (recoveries: 80.5–114.7%) and 1–130 ng mL−1 for alpha-fetoprotein.

Fig. 6.

a Schematic of MOF-based SERS platform and b SERS spectra of rhodamine 6G on Au NP/MIL-101 substrate (blue lines), Au colloids substrate (red line), and MIL-101 (black line).

Reprinted with permission from [89]. Copyright (2014) American Chemical Society. (Color figure online)

MOF-Based Gas Sensors

MOFs have large intrinsic porosities with > 90% free volumes, adjustable internal surface areas [90–93], and a high degree of crystallinity, which enable the adsorption of guest molecules through strong host–guest interactions [94, 95]. The sustainable pores within MOFs provide a natural habitat for guest molecules, thus increasing the chances for guest–host interactions and the sensing sensitivity [95]. While the sensitivity depends partly on the method of signal transduction, it mainly depends on the strength of analyte binding to the MOF. Thus, stronger binding leads to higher responses [96]. Owing to their unique physical and chemical properties, MOF-based materials show significant promise as sensing materials not only in water contaminant detection but also for gases.

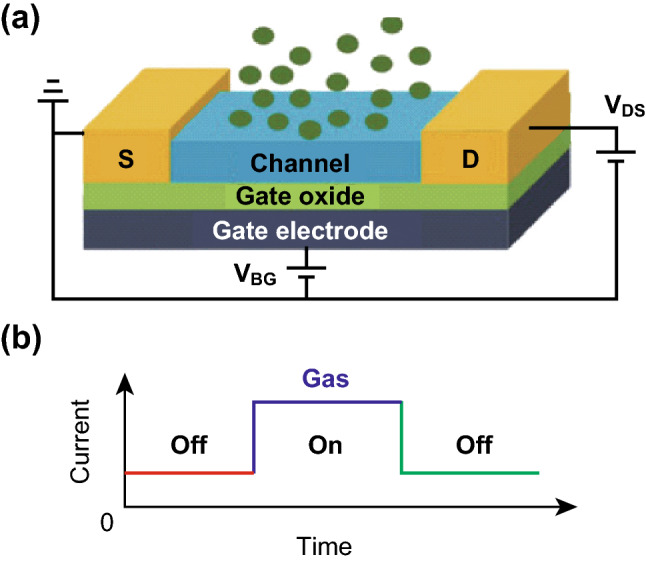

An FET gas sensor is composed of source and drain electrodes, channel material, gate oxide, and gate electrode [97] (Fig. 7a). The channel material is the key to monitoring the conductance change in the sensor by the physically adsorbed target gases. Therefore, intrinsic properties such as the work function, carrier mobility, and band gap of the channel material determine the sensing performance. The conductance in the channel materials can increase or decrease (depending on the type of the semiconductor and reducing or oxidizing gas) during the interaction between the channel material and gas (Fig. 7b). The adsorbed gas molecules can change the local carrier concentration in the channel material, which leads to the conductance change [98]. FET sensors have been widely used in gas detection as they need no chemical agents and can respond to low-concentration gases instantaneously. Recently, MOF-based materials were applied to FET sensors as the sensing channel or combined with other gas-sensitive materials to improve the sensing capability.

Fig. 7.

a Schematic illustration of FET sensor with source and drain electrodes, channel material, gate oxide, and gate electrode. b Sensor current change after gas adsorption and desorption.

Reprinted with permission from [97]. Copyright (2017) Royal Society of Chemistry

For gas sensing applications, the large capacity and highly selective gas adsorption properties of MOFs are utilized to improve the sensor performance [99–101]. Composite structures that take advantage of the sensitivity of semiconductors and the selectivity of MOFs are desirable [73, 102]. Dinca and coworkers reported on conductive MOF-based FET sensors for ammonia sensing and achieved good sensing performance [109]. He et al. demonstrated noble-metal@MOF composites with highly selective sensing properties to volatile organic compounds, in which the sensor could detect 0.25 ppm formaldehyde at room temperature [111]. To develop highly sensitive and selective FET gas sensors, many studies have focused on developing hybrid nanostructures constructed with MOFs and noble metals or transition metal oxides such as Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 [103], Au@ZnO@ZIF-8 [104], and Au@MOF-5 (Zn4O(BDC)3) [105].

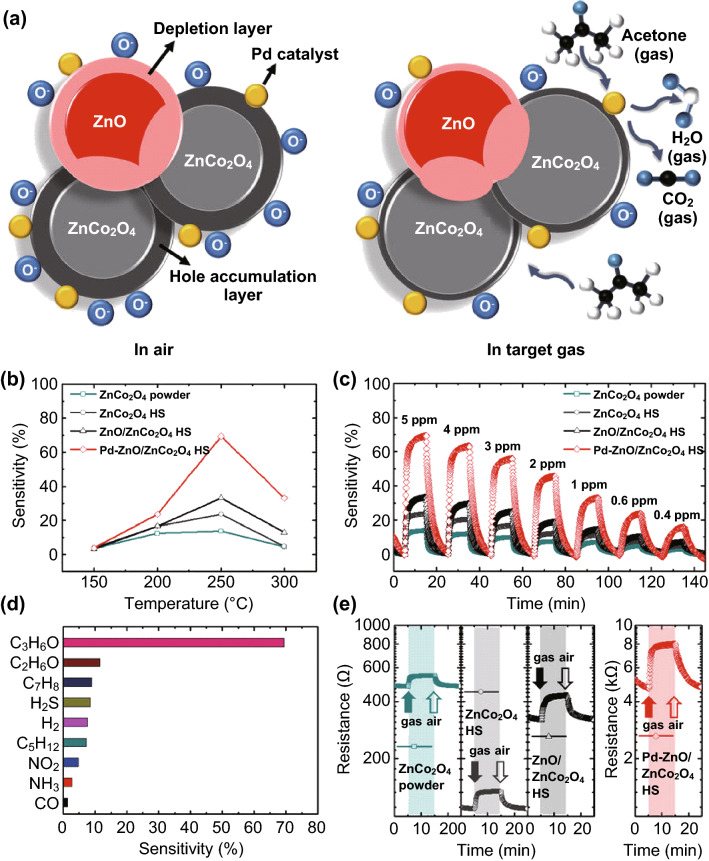

Using Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres, Koo et al. [103] reported a highly sensitive acetone sensor (as shown in Fig. 8a). The ZnCo2O4 is a p-type semiconductor. Oxygen molecules in the air adsorb on its surface and deprive its electron, followed by creating a hole accumulation on its surface through reactions between chemisorbed oxygen species (O2−, O−, and O2−) and a reducing gas such as acetone. As a result, ZnCo2O4 exhibited high response to acetone (sensitivity = 14% to 5 ppm at 250 °C). The outstanding sensing performance of the sensors is owing to several reasons. At first, the Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres with high surface area provide many binding sites for acetone, which raises the reaction efficiency. Second, n-type ZnO induces a p–n junction in p-type ZnCo2O4, followed by recombination between the electron in ZnO and the hole in ZnCo2O4, thus reducing the hole concentration in ZnCo2O4. Moreover, the sensor resistance increases because an electronic sensitizer such as Pd has good catalytic properties and can decrease the activation energy [19, 106]. The additional electrons recombine with holes in Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4, and the hole accumulation layer is significantly decreased. Therefore, the acetone sensing response is dramatically increased by the Pd catalyst.

Fig. 8.

a Schematic of acetone sensing mechanism with Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres. b Temperature-dependent acetone sensing characteristics to 5 ppm in temperature range of 150–300 °C. c Dynamic acetone sensing responses in concentration range of 0.4–5 ppm at 250 °C of ZnCo2O4 powders, ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres, ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres, and Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres. d Selective acetone detection characteristics of Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres. e Dynamic resistance transition properties of samples toward 5 ppm acetone at 250 °C.

Reprinted with permission from [103]. Copyright (2017) Macmillan Publishers Limited

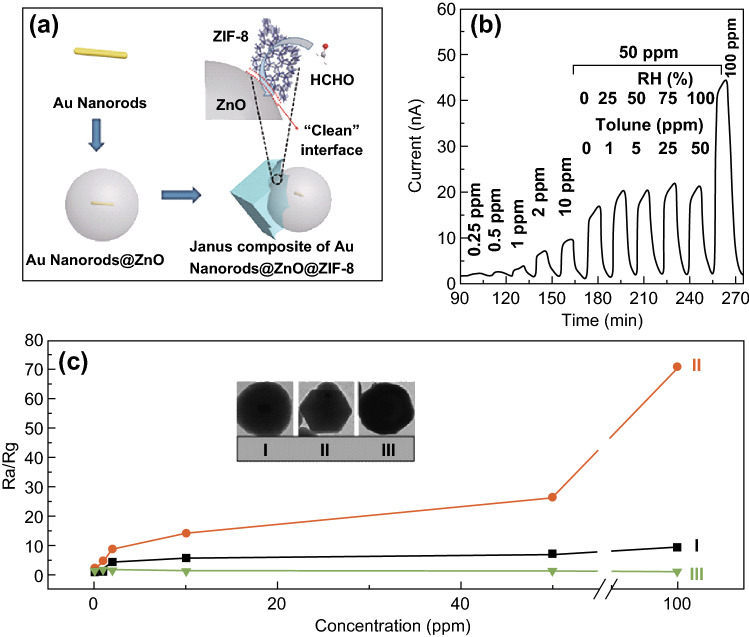

Another example of an MOF gas sensor was demonstrated by Wang [104], who synthesized a novel composite structure of Au@ZnO@ZIF-8 to simultaneously detect and remove VOCs with photo-induced gas sensing (Fig. 9). Three moieties within the dual-functional nanomaterials were synthesized via an anisotropic growth method. The synergistic effects in sensing and removing were achieved by the plasmonic Au nanorods for plasmonic resonance to enhance the photocatalysis of ZnO, a semiconductor ZnO for high conductivity [106–108], and ZIF-8 for improving the gas adsorption capability.

Fig. 9.

a Schematic illustration of anisotropic synthesis of Au@ZnO@ZIF-8. b Dynamic response of Au@ZnO@ZIF-8 to HCHO with concentrations from 0.25 to 100 ppm. c Plots of sensor responses to HCHO concentration of three samples: (I) pristine Au@ZnO, (II) synthetic Au@ZnO@ZIF-8, and (III) completed Au@ZnO@ZIF-8. Inset shows TEM images of samples.

Reprinted with permission from [104]. Copyright (2017) Springer

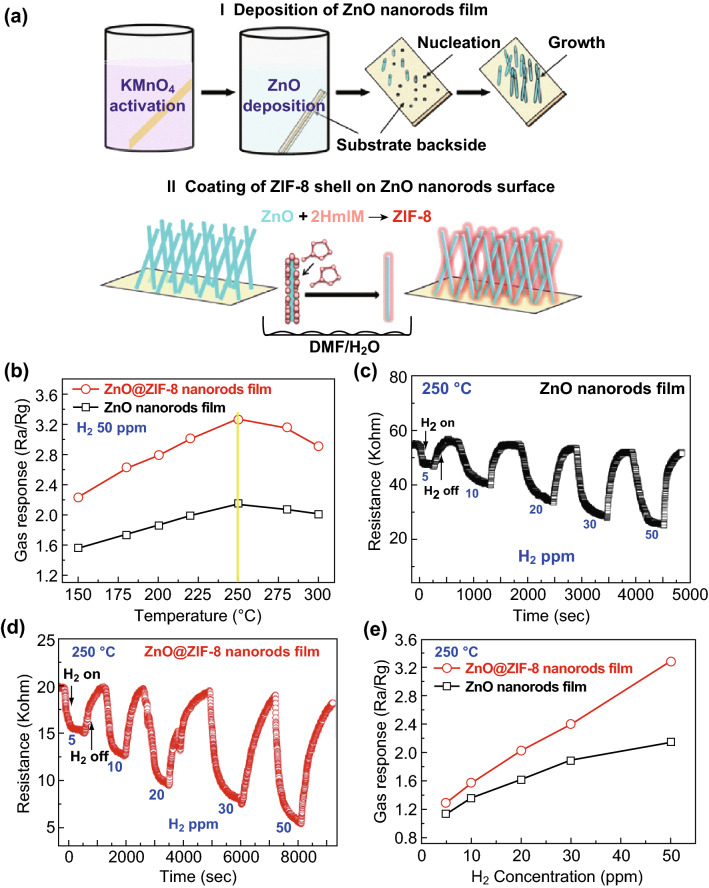

As for the practical applications of gas sensors, MOF-based films have attracted considerable attention owing to their relatively large exposure area to gas and their high stability in the target gas flow [109]. In a recent study, a ZnO@ZIF-8 core–shell nanorod film (thickness of 100 nm) was synthesized to detect H2 over CO2 through a facile solution deposition process [110]. The ZnO nanorod film was grown on a KMnO4-activated glass substrate to form a nanorod structure and ensure direct contact between the film and substrate. The ZIF-8 material had huge cavities of 11.6 Å diameter as well as short pore apertures of 3.4 Å, which exhibited effective separation of H2 (2.9 Å) from CO (3.7 Å) owing to the molecular sieving effect [110, 111]. Thus, thin ZnO nanorod film is favorable for H2 diffusion owing to its open structure, while ZIF-8 enhances the selectivity of H2 sensing over other gases. This sensor can detect low concentrations of H2 of 5–50 ppm at 200 °C (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

a Preparation of ZnO@ZIF-8 core–shell nanorod films. b Temperature-dependent response curves of ZnO nanorod and ZnO@ZIF-8 sensors to 50 ppm H2. c, d Dynamic response curves of two sensors to different H2 concentrations at 250 °C. e Concentration-dependent H2 response curves of two sensors at 250 °C.

Reprinted with permission from [110]. Copyright (2017) John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

MOF sensors based on other sensing mechanisms have also been demonstrated for gas detection. The Salama group fabricated a chemical capacitive sensor for the detection of sulfur dioxide (SO2) at room temperature [112]. The sensing layer was fabricated with indium MOF (MFM-300), which was deposited on a functionalized capacitive interdigitated electrode. The fabricated sensor exhibited high sensitivity to SO2 at concentrations down to 75 ppb and a detection limit of 5 ppb. This remarkable detection is owing to the associated changes in film permittivity upon the adsorption of SO2 molecules. The MFM-300 sensor also showed desirable detection selectivity toward SO2 in the presence of CH4, CO2, NO2, and H2.

Dou and coworkers demonstrated a luminescent MOF film sensor [MIL-100(In) ⊃ Tb3+]. This sensor works by quenching the luminescence of the MOF film through bimolecular collisions with O2, which possesses high sensitivity and fast response to O2 sensing [113]. In another study, Zhang and coworkers introduced Eu3+ ions to the free -COOH sites of MIL-124 ligand channels to detect low concentrations of NH3 in ambient air, and achieved good sensing performance [114]. The Eddaoudi group utilized the thin film of rare-earth metal (RE)-based MOFs as a sensing platform for the detection of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) at room temperature [115]. The RE-MOF offers a distinctive H2S detection of concentrations down to 100 ppb with a limit of detection of 5.4 ppb.

To summarize, MOF-based gas sensors have been demonstrated in various gas detection approaches with good sensing performance in terms of fast response and recovery, high sensitivity, high selectivity, and simple test procedures.

Conclusion and Outlook

Table 1 summarizes MOF-based sensors relying on optical, electrochemical, and FET signals for environmental contaminant sensing. MOFs have been demonstrated as sensing materials for heavy metal, anion, organic compound, and gas detection owing to their unique structure and properties such as large surface area and tunable porosity, reversible adsorption, high catalytic ability, and tunable chemical functionalization. As discussed, MOF-based materials have shown outstanding sensor performance, which can be further improved by combining with other functional materials. For instance, lanthanide-based MOFs (Ln-MOFs) and fluorophore-modified MOFs are promising sensing materials in luminescent sensors as the guest molecules incorporated in MOF can emit or induce luminescence. The combination with high conductive materials (e.g., carbon nanomaterials and noble metals) endows MOF with better stability and electroconductivity when used in electrochemical sensors. In addition, the functional groups incorporated with MOFs can specifically recognize the target analytes and enhance the sensing selectivity.

Table 1.

MOF-based sensors for water and gas contaminant detection

| Sensing material | Method | Target contaminant | LOD | Environmental sample test | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu(III)@UMOFs | luminescent | Hg2+, Ag+ and S2− | [116] | ||

| UiO-66-NH2 | luminescent | PO43− | 1.25 μM | [117] | |

| APTMS–ZnO QDs@MOF-5 | luminescent | PO43− | 53 nM | [55] | |

| UiO-66-NH2 | luminescent | Hg2+ | 17.6 nM | [118] | |

| NH2-MIL-53(Al) | luminescent | ClO− | 0.04 μM | tap and swimming pool water | [57] |

| CDs@Eu-DPA MOFs | luminescent | Cu2+ | 26.3 nM | real water | [119] |

|

Eu–Zn (1·NO3−) Tb–Zn (2·NO3−) |

luminescent | I− | 0.001 ppM | [120] | |

| Eu–UiO–66(Zr)–(COOH)2 | luminescent | Cd2+ | 0.06 μM | environmental water | [121] |

| Zn3(TDPAT)–(H2O)3 | luminescent | nitrobenzene | 50 ppM | [122] | |

| H2O ⊂ CuI-MOF | luminescent | volatile organic compounds | 1 ppm | [123] | |

| Zn4O(BDC)3 | electrochemical | Pb2+ | 4.9 nM | real water | [124] |

| Cu-MOF/rGO | electrochemical | NO2− | 33 nM | pond water | [78] |

| UiO-66-NH2 | electrochemical | NO2− | 0.01 μM | [125] | |

| Cu3(BTC)2 | electrochemical | 2,4-dichlorophenol | 9 nM | reservoir raw water | [84] |

| Me2NH2@MOF-1 | electrochemical | Cu2+ | 1 pM | river water | [126] |

| Cu-MOF-199/SWCTs | electrochemical | Hydroquinone and catechol | 0.08 and 1 μM | river water | [127] |

| RuUiO-67 | colorimetric | Hg2+ | 0.5 μM | [87] | |

| Tb1.7Eu0.3(BDC)3·(H2O)4 | colorimetric | Cd2+ | 0.25 mM | lead-polluted water samples | [128] |

| Pd–ZnO/ZnCo2O4 | FET | acetone | 0.4–5 ppm | [103] | |

| Cu3(HITP)2 | FET | ammonia | 0.5–10 ppm | [73] | |

| ZnO@ZIF-8 | FET | formaldehyde | 10–200 ppm | [129] | |

| ZIF-67 | FET | formaldehyde | 5–500 ppm | [111] |

Although MOF-based materials have shown a lot of promise, future work is still needed to improve the sensor performance in terms of sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and reusability. First, the function of MOF in each sensing platform should be better understood to fully utilize the advantages of MOF and to assist with sensor design and performance optimization. Second, it is worthwhile to further broaden the MOF category with new useful properties such as plasmonic, electrical, and thermochromic properties. This will provide more opportunities in sensor design and integration. Third, MOF’s pore structure is critical to many sensing application, and new synthesis or surface functionalization methods are needed to better tune the MOF structure and enhance its sensing activity and stability. In electrochemical and FET sensors, the sensing materials not only need to have high activity but also acceptable conductivity. Therefore, the conductivity of MOF should be increased by either developing conductive MOF materials or combining MOF with other conductive substrates, e.g., conductive nanocarbons. Moreover, the stability of MOF-based sensing materials needs to be improved, especially for sensors that work under an acid condition. Finally, most of the sensor demonstrations were conducted using laboratory-prepared samples. Therefore, the sensor performance in a complex environmental media, such as real water, needs to be evaluated and the sensor selectivity and reliability should be improved as they are the two major critical requirements for practical use of the sensors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21707102) and 1000 Talents Plan of China.

Footnotes

Xian Fang and Boyang Zong have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lustig WP, Mukherjee S, Rudd ND, Desai AV, Li J, Ghosh SK. Metal–organic frameworks: functional luminescent and photonic materials for sensing applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46(11):3242–3285. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00930a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrovic M, Farre M, de Alda ML, Perez S, Postigo C, Kock M, Radjenovic J, Gros M, Barcelo D. Recent trends in the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of organic contaminants in environmental samples. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010;1217(25):4004–4017. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Nuijs ALN, Tarcomnicu I, Covaci A. Application of hydrophilic interaction chromatography for the analysis of polar contaminants in food and environmental samples. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218(35):5964–5974. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falcaro P, Ricco R, Yazdi A, Imaz I, Furukawa S, Maspoch D, Ameloot R, Evans JD, Doonan CJ. Application of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles@MOFs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016;307:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Jiu JT, Araki T, Nogi M, Sugahara T, Nagao S, Koga H, He P, Suganuma K. Silver nanowire electrodes: conductivity improvement without post-treatment and application in capacitive pressure sensors. Nano-Micro Lett. 2015;7(1):51–58. doi: 10.1007/s40820-014-0018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Li ZH, Xu MH, Ma YJ, Zhang J, Su YJ, Gao F, Wei H, Zhang LY. Controllable synthesis of fluorescent carbon dots and their detection application as nanoprobes. Nano-Micro Lett. 2013;5(4):247–259. doi: 10.5101/nml.v5i4.p247-259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moldovan O, Iniguez B, Deen MJ, Marsal LF. Graphene electronic sensors—review of recent developments and future challenges. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 2015;9(6):446–453. doi: 10.1049/iet-cds.2015.0259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Zhou G, Mao S, Chen J. Rapid detection of nutrients with electronic sensors: a review. Environ.-Sci. Nano. 2018;5(4):837–862. doi: 10.1039/c7en01160a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang Y, Wang E. Electrochemical biosensors on platforms of graphene. Chem. Commun. 2013;49(83):9526–9539. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44735a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao S, Wen ZH, Ci SQ, Guo XR, Ostrikov K, Chen JH. Perpendicularly oriented MoSe2/graphene nanosheets as advanced electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. Small. 2015;11(4):414–419. doi: 10.1002/smll.201401598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhotra R, Patel V, Vaque JP, Gutkind JS, Rusling JF. Ultrasensitive electrochemical immunosensor for oral cancer biomarker IL-6 using carbon nanotube forest electrodes and multilabel amplification. Anal. Chem. 2010;82(8):3118–3123. doi: 10.1021/ac902802b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bo Z, Yuan M, Mao S, Chen X, Yan JH, Cen KF. Decoration of vertical graphene with tin dioxide nanoparticles for highly sensitive room temperature formaldehyde sensing. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018;256:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao S, Pu HH, Chang JB, Sui XY, Zhou GH, Ren R, Chen YT, Chen JH. Ultrasensitive detection of orthophosphate ions with reduced graphene oxide/ferritin field-effect transistor sensors. Environ.-Sci. Nano. 2017;4(4):856–863. doi: 10.1039/c6en00661b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang X, Ren HX, Zhao H, Li ZX. Ultrasensitive visual and colorimetric determination of dopamine based on the prevention of etching of silver nanoprisms by chloride. Microchim. Acta. 2017;184(2):415–421. doi: 10.1007/s00604-016-2024-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Wang SX, Zhang K, Jiang XY. Visual detection of copper(II) by azide- and alkyne-functionalized gold nanoparticles using click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47(39):7454–7456. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arya SK, Saha S, Ramirez-Vick JE, Gupta V, Bhansali S, Singh SP. Recent advances in ZnO nanostructures and thin films for biosensor applications: review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;737:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huo X, Liu P, Zhu J, Liu X, Ju H. Electrochemical immunosensor constructed using TiO2 nanotubes as immobilization scaffold and tracing tag. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;85:698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu SL, Zhang JX, Tu WW, Bao JC, Dai ZH. Using ruthenium polypyridyl functionalized ZnO mesocrystals and gold nanoparticle dotted graphene composite for biological recognition and electrochemiluminescence biosensing. Nanoscale. 2014;6(4):2419–2425. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05944h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang WH, Ma W, Long YT. Redox-mediated indirect fluorescence immunoassay for the detection of disease biomarkers using dopamine-functionalized quantum dots. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(10):5131–5136. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang GQ, Chen ZP, Chen LX. Mesoporous silica-coated gold nanorods: towards sensitive colorimetric sensing of ascorbic acid via target-induced silver overcoating. Nanoscale. 2011;3(4):1756–1759. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00863j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha JH, Han JI, Choi Y, Yoon DS, Oh KW, Lim G. DNA hybridization electrochemical sensor using conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2003;18(10):1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0956-5663(03)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Y, Meng J, Meng LX, Dong Y, Cheng YX, Zhu CJ. A highly selective fluorescence-based polymer sensor incorporating an (r, r)-salen moiety for Zn2+ detection. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16(43):12898–12903. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janiak C, Vieth JK. MOFs, MILs and more: concepts, properties and applications for porous coordination networks (PCNs) New J. Chem. 2010;34(11):2366–2388. doi: 10.1039/c0nj00275e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaghi OM, Li GM, Li HL. Selective binding and removal of guests in a microporous metal–organic framework. Nature. 1995;378(6558):703–706. doi: 10.1038/378703a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Eddaoudi M, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal–organic framework. Nature. 1999;402(6759):276–279. doi: 10.1038/46248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li SZ, Huo FW. Metal–organic framework composites: from fundamentals to applications. Nanoscale. 2015;7(17):7482–7501. doi: 10.1039/c5nr00518c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farha OK, Eryazici I, Jeong NC, Hauser BG, Wilmer CE, et al. Metal–organic framework materials with ultrahigh surface areas: is the sky the limit? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(36):15016–15021. doi: 10.1021/ja3055639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng Y, Krungleviciute V, Eryazici I, Hupp JT, Farha OK, Yildirim T. Methane storage in metal–organic frameworks: current records, surprise findings, and challenges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135(32):11887–11894. doi: 10.1021/ja4045289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald TM, Mason JA, Kong XQ, Bloch ED, Gygi D, et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal–organic frameworks. Nature. 2015;519(7543):303–308. doi: 10.1038/nature14327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horcajada P, Serre C, Vallet-Regi M, Sebban M, Taulelle F, Ferey G. Metal–organic frameworks as efficient materials for drug delivery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45(36):5974–5978. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chowdhuri AR, Laha D, Chandra S, Karmakar P, Sahu SK. Synthesis of multifunctional upconversion NMOFs for targeted antitumor drug delivery and imaging in triple negative breast cancer cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;319:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui XL, Chen KJ, Xing HB, Yang QW, Krishna R, et al. Pore chemistry and size control in hybrid porous materials for acetylene capture from ethylene. Science. 2016;353(6295):141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui L, Wu J, Li J, Ju H. Electrochemical sensor for lead cation sensitized with a DNA functionalized porphyrinic metal–organic framework. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(20):10635–10641. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu ZC, Deibert BJ, Li J. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43(16):5815–5840. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00010b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lian X, Yan B. Phosphonate MOFs composite as off-on fluorescent sensor for detecting purine metabolite uric acid and diagnosing hyperuricuria. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56(12):6802–6808. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b03009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng L, Cheng QG, Kim C, Gao WY, Wojtas L, Chen YS, Zaworotko MJ, Zhang XP, Ma SQ. Crystal engineering of a microporous, catalytically active fcu topology MOF using a custom-designed metalloporphyrin linker. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51(40):10082–10085. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xamena FXLI, Casanova O, Tailleur RG, Garcia H, Corma A. Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) as catalysts: a combination of Cu2+ and Co2+ MOFs as an efficient catalyst for tetralin oxidation. J. Catal. 2008;255(2):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2008.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Li J, Yue G, Luo X. Novel Ag@Nitrogen-doped porous carbon composite with high electrochemical performance as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 2017;9:32. doi: 10.1007/s40820-017-0131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park KM, Kim H, Murray J, Koo J, Kim K. A facile preparation method for nanosized MOFs as a multifunctional material for cellular imaging and drug delivery. Supramol. Chem. 2017;29(6):441–445. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2016.1266359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu DM, Lu KD, Poon C, Lin WB. Metal–organic frameworks as sensory materials and imaging agents. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53(4):1916–1924. doi: 10.1021/ic402194c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chidambaram A, Stylianou KC. Electronic metal–organic framework sensors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018;5:979–998. doi: 10.1039/c7qi00815e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stavila V, Talin AA, Allendorf MD. MOF-based electronic and opto-electronic devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43(16):5994–6010. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00096j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar V, Kim KH, Kumar P, Jeon BH, Kim JC. Functional hybrid nanostructure materials: advanced strategies for sensing applications toward volatile organic compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;342:80–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui YJ, Yue YF, Qian GD, Chen BL. Luminescent functional metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012;112(2):1126–1162. doi: 10.1021/cr200101d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Yang L, Zhao L, Wang XL, Shao KZ, Su ZM. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks with anthracene chromophores: small-molecule sensing and highly selective sensing for nitro explosives. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016;16(8):4374–4382. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b00482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang M, Feng GX, Song ZG, Zhou YP, Chao HY, et al. Two-dimensional metal–organic framework with wide channels and responsive turn-on fluorescence for the chemical sensing of volatile organic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(20):7241–7244. doi: 10.1021/ja502643p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang SY, Shi W, Cheng P, Zaworotko MJ. A mixed-crystal lanthanide zeolite-like metal–organic framework as a fluorescent indicator for lysophosphatidic acid, a cancer biomarker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(38):12203–12206. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou JM, Li HH, Zhang H, Li HM, Shi W, Cheng P. A bimetallic lanthanide metal–organic material as a self-calibrating color-gradient luminescent sensor. Adv. Mater. 2015;27(44):7072–7077. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li HH, Shi W, Zhao KN, Niu Z, Li HM, Cheng P. Highly selective sorption and luminescent sensing of small molecules demonstrated in a multifunctional lanthanide microporous metalorganic framework containing 1D honeycomb-type channels. Chem.-Eur. J. 2013;19(10):3358–3365. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao B, Chen XY, Cheng P, Liao DZ, Yan SP, Jiang ZH. Coordination polymers containing 1D channels as selective luminescent probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(47):15394–15395. doi: 10.1021/ja047141b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao B, Cheng P, Chen XY, Cheng C, Shi W, Liao DZ, Yan SP, Jiang ZH. Design and synthesis of 3d–4f metal-based zeolite-type materials with a 3D nanotubular structure encapsulated “water” pipe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126(10):3012–3013. doi: 10.1021/ja038784e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu SY, Lin YN, Liu JW, Shi W, Yang GM, Cheng P. Rapid detection of the biomarkers for carcinoid tumors by a water stable luminescent lanthanide metal–organic framework sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28(17):1707169. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201707169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolliopoulos AV, Kampouris DK, Banks CE. Rapid and portable electrochemical quantification of phosphorus. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(8):4269–4274. doi: 10.1021/ac504602a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu H, Xiao YQ, Rao XT, Dou ZS, Li WF, Cui YJ, Wang ZY, Qian GD. A metal–organic framework for selectively sensing of PO43− anion in aqueous solution. J. Alloys Compd. 2011;509(5):2552–2554. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.11.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao D, Wan XY, Song HJ, Hao LY, Su YY, Lv Y. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) combined with ZnO quantum dots as a fluorescent sensing platform for phosphate. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014;197:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2014.02.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu H, Cao CS, Zhao B. A water-stable lanthanide-organic framework as a recyclable luminescent probe for detecting pollutant phosphorus anions. Chem. Commun. 2015;51(51):10280–10283. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02596f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu T, Zhang LC, Sun MX, Deng DY, Su YY, Lv Y. Amino-functionalized metal–organic frameworks nanoplates-based energy transfer probe for highly selective fluorescence detection of free chlorine. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(6):3413–3420. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karmakar A, Kumar N, Samanta P, Desai AV, Ghosh SK. A post-synthetically modified MOF for selective and sensitive aqueous-phase detection of highly toxic cyanide ions. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22(3):864–868. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin XM, Gao GM, Zheng LY, Chi YW, Chen GN. Encapsulation of strongly fluorescent carbon quantum dots in metal–organic frameworks for enhancing chemical sensing. Anal. Chem. 2014;86(2):1223–1228. doi: 10.1021/ac403536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin X, Luo F, Zheng L, Gao G, Chi Y. Fast, sensitive, and selective ion-triggered disassembly and release based on tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II)-functionalized metal–organic frameworks. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(9):4864–4870. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Q, Wang CJ, Tan HL, Tang GE, Gao J, Chen CH. A turn on fluorescent sensor based on lanthanide coordination polymer nanoparticles for the detection of mercury(II) in biological fluids. RSC Adv. 2016;6(22):17811–17817. doi: 10.1039/c5ra26849d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kesselmeier J, Staudt M. Biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOC): an overview on emission, physiology and ecology. J. Atmos. Chem. 1999;33(1):23–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1006127516791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y, Yan B. A responsive MOF nanocomposite for decoding volatile organic compounds. Chem. Commun. 2016;52(11):2265–2268. doi: 10.1039/c5cc09029f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tehrani AA, Esrafili L, Abedi S, Morsali A, Carlucci L, Proserpio DM, Wang J, Junk PC, Liu TF. Urea metal–organic frameworks for nitro-substituted compounds sensing. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56(3):1446–1454. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei JZ, Wang XL, Sun XJ, Hou Y, Zhang X, Yang DD, Dong H, Zhang FM. Rapid and large-scale synthesis of IRMOF-3 by electrochemistry method with enhanced fluorescence detection performance for TNP. Inorg. Chem. 2018;57(7):3818–3824. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b03174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou Y, Yang Q, Zhang D, Gan N, Li Q, Cuan J. Detection and removal of antibiotic tetracycline in water with a highly stable luminescent MOF. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018;262:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.01.218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Liu Y, Li Z, Li J. Sensitive electrochemical aptamer biosensor for dynamic cell surface N-glycan evaluation featuring multivalent recognition and signal amplification on a dendrimer-graphene electrode interface. Anal. Chem. 2014;86(9):4278–4286. doi: 10.1021/ac404070m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fang X, Liu JF, Wang J, Zhao H, Ren HX, Li ZX. Dual signal amplification strategy of Au nanopaticles/ZnO nanorods hybridized reduced graphene nanosheet and multienzyme functionalized Au@ZnO composites for ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of tumor biomarker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017;97:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Hou C, Zhang Y, He F, Liu MZ, Li XL. Preparation of graphene nano-sheet bonded PDA/MOF microcapsules with immobilized glucose oxidase as a mimetic multi-enzyme system for electrochemical sensing of glucose. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016;4(21):3695–3702. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00276e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang C, Wang XR, Hou M, Li XY, Wu XL, Ge J. Immobilization on metal–organic framework engenders high sensitivity for enzymatic electrochemical detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(16):13831–13836. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu XQ, Ma JG, Li H, Chen DM, Gu W, Yang GM, Cheng P. Metal–organic framework biosensor with high stability and selectivity in a bio-mimic environment. Chem. Commun. 2015;51(44):9161–9164. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02113h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheberla D, Sun L, Blood-Forsythe MA, Er S, Wade CR, Brozek CK, Aspuru-Guzik A, Dinca M. High electrical conductivity in Ni(3)(2,3,6,7,10,11-hexaiminotriphenylene)(2), a semiconducting metal–organic graphene analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(25):8859–8862. doi: 10.1021/ja502765n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campbell MG, Sheberla D, Liu SF, Swager TM, Dinca M. Cu(3)(hexaiminotriphenylene)(2): an electrically conductive 2D metal–organic framework for chemiresistive sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54(14):4349–4352. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang X, Wang QX, Wang QH, Gao F, Gao F, Yang YZ, Guo HX. Highly dispersible and stable copper terephthalate metal–organic framework-graphene oxide nanocomposite for an electrochemical sensing application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(14):11573–11580. doi: 10.1021/am5019918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu ZD, Yang LZ, Xu CL. Pt@UiO-66 heterostructures for highly selective detection of hydrogen peroxide with an extended linear range. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(6):3438–3444. doi: 10.1021/ac5047278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yu YJ, Yu C, Niu YZ, Chen J, Zhao YL, Zhang YC, Gao RF, He JL. Target triggered cleavage effect of DNAzyme: relying on Pd–Pt alloys functionalized Fe-MOFs for amplified detection of Pb2+ Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018;101:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo HX, Wang DF, Chen JH, Weng W, Huang MQ, Zheng ZS. Simple fabrication of flake-like NH2-MIL-53(Cr) and its application as an electrochemical sensor for the detection of Pb2+ Chem. Eng. J. 2016;289:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.12.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saraf M, Rajak R, Mobin SM. A fascinating multitasking Cu-MOF/rGO hybrid for high performance supercapacitors and highly sensitive and selective electrochemical nitrite sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4(42):16432–16445. doi: 10.1039/c6ta06470a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perry DA, Razer TM, Primm KM, Chen T, Shamburger JB, et al. Surface-enhanced infrared absorption and density functional theory study of dihydroxybenzene isomer adsorption on silver nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117(16):8170–8179. doi: 10.1021/jp3121462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang Y, Wang Q, Qiu W, Guo H, Gao F. Covalent immobilization of Cu3(btc)2 at chitosan–electroreduced graphene oxide hybrid film and its application for simultaneous detection of dihydroxybenzene isomers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120(18):9794–9803. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b01574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou X, Yan X, Hong Z, Zheng X, Wang F. Design of magnetic core–shell Ni@graphene composites as a novel electrochemical sensing platform. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018;255:2959–2962. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.09.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li J, Xia J, Zhang F, Wang Z, Liu Q. An electrochemical sensor based on copper-based metal–organic frameworks-graphene composites for determination of dihydroxybenzene isomers in water. Talanta. 2018;181:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huang SS, Qu YX, Li RN, Shen J, Zhu LW. Biosensor based on horseradish peroxidase modified carbon nanotubes for determination of 2,4-dichlorophenol. Microchim. Acta. 2008;162(1–2):261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00604-007-0872-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dong S, Suo G, Li N, Chen Z, Peng L, Fu Y, Yang Q, Huang T. A simple strategy to fabricate high sensitive 2,4-dichlorophenol electrochemical sensor based on metal organic framework Cu3(BTC)2. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2016;222:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.09.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kong BA, Zhu AW, Luo YP, Tian Y, Yu YY, Shi GY. Sensitive and selective colorimetric visualization of cerebral dopamine based on double molecular recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50(8):1837–1840. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen L, Fu X, Lu W, Chen L. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric sensing of Hg2+ based on the morphology transition of silver nanoprisms. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5(2):284–290. doi: 10.1021/am3020857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Z, Yang J, Li Y, Zhuang Q, Gu J. Zr-based MOFs integrated with chromophoric ruthenium complex for specific and reversible Hg2+ sensing. Dalton Trans. 2018;47(16):5570–5574. doi: 10.1039/c8dt00569a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang S, Slotcavage D, Mai JD, Guo F, Li S, Zhao Y, Lei Y, Cameron CE, Huang TJ. Electrochemically created highly surface roughened Ag nanoplate arrays for SERS biosensing applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2014;2(39):8350–8356. doi: 10.1039/C4TC01276C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hu Y, Liao J, Wang D, Li G. Fabrication of gold nanoparticle-embedded metal–organic framework for highly sensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering detection. Anal. Chem. 2014;86(8):3955–3963. doi: 10.1021/ac5002355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lv Y, Yu H, Xu P, Xu J, Li X. Metal organic framework of MOF-5 with hierarchical nanopores as micro-gravimetric sensing material for aniline detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2018;256:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.09.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xia H, Zhang J, Yang Z, Guo S, Guo S, Xu Q. 2D MOF Nanoflake-assembled spherical microstructures for enhanced supercapacitor and electrocatalysis performances. Nano-Micro Lett. 2017;9:43. doi: 10.1007/s40820-017-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li B, Wen HM, Zhou W, Chen B. Porous metal–organic frameworks for gas storage and separation: what, how, and why? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5(20):3468–3479. doi: 10.1021/jz501586e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun CY, Wang XL, Zhang X, Qin C, Li P, et al. Efficient and tunable white-light emission of metal–organic frameworks by iridium-complex encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2717. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou HC, Long JR, Yaghi OM. Introduction to metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2012;112(2):673–674. doi: 10.1021/cr300014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Y, Bai X, Wang X, Shiu KK, Zhu Y, Jiang H. Highly sensitive graphene-Pt nanocomposites amperometric biosensor and its application in living cell H2O2 detection. Anal. Chem. 2014;86(19):9459–9465. doi: 10.1021/ac5009699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kreno LE, Leong K, Farha OK, Allendorf M, Van Duyne RP, Hupp JT. Metal–organic framework materials as chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 2012;112(2):1105–1125. doi: 10.1021/cr200324t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mao S, Chang J, Pu H, Lu G, He Q, Zhang H, Chen J. Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based field-effect transistors for chemical and biological sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46(22):6872–6904. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00827e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mao S, Lu G, Chen J. Nanocarbon-based gas sensors: progress and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2(16):5573–5579. doi: 10.1039/c3ta13823b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.George T, Lee JH, Islam MS, Houk RTJ, Robinson A, et al. Investigation of microcantilever array with ordered nanoporous coatings for selective chemical detection. Proc. SPIE. 2010;7679:767927–797929. doi: 10.1117/12.850217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klein N, Herzog C, Sabo M, Senkovska I, Getzschmann J, Paasch S, Lohe MR, Brunner E, Kaskel S. Monitoring adsorption-induced switching by (129)Xe NMR spectroscopy in a new metal–organic framework Ni(2)(2,6-ndc)(2)(dabco) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010;12(37):11778–11784. doi: 10.1039/c003835k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Venkatasubramanian A, Lee J-H, Stavila V, Robinson A, Allendorf MD, Hesketh PJ. MOF@MEMS: design optimization for high sensitivity chemical detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2012;168:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2012.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Campbell MG, Liu SF, Swager TM, Dinca M. Chemiresistive sensor arrays from conductive 2D metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(43):13780–13783. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koo WT, Choi SJ, Jang JS, Kim ID. Metal–organic framework templated synthesis of ultrasmall catalyst loaded ZnO/ZnCo2O4 hollow spheres for enhanced gas sensing properties. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45074. doi: 10.1038/srep45074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang D, Li Z, Zhou J, Fang H, He X, Jena P, Zeng J-B, Wang W-N. Simultaneous detection and removal of formaldehyde at room temperature: janus Au@ZnO@ZIF-8 nanoparticles. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018;10(1):4. doi: 10.1007/s40820-017-0158-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.He L, Liu Y, Liu J, Xiong Y, Zheng J, Liu Y, Tang Z. Core–shell noble-metal@metal–organic-framework nanoparticles with highly selective sensing property. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52(13):3741–3745. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koo WT, Choi SJ, Kim SJ, Jang JS, Tuller HL, Kim ID. Heterogeneous sensitization of metal–organic framework driven metal@metal oxide complex catalysts on an oxide nanofiber scaffold toward superior gas sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(40):13431–13437. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhai J, Wang L, Wang D, Li H, Zhang Y, He DQ, Xie T. Enhancement of gas sensing properties of CdS nanowire/ZnO nanosphere composite materials at room temperature by visible-light activation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2011;3(7):2253–2258. doi: 10.1021/am200008y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wan Q, Li QH, Chen YJ, Wang TH, He XL, Li JP, Lin CL. Fabrication and ethanol sensing characteristics of ZnO nanowire gas sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84(18):3654–3656. doi: 10.1063/1.1738932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu B. Metal–organic framework-based devices: separation and sensors. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22(20):10094–10101. doi: 10.1039/c2jm15827b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu X, Xiong S, Mao Z, Hu S, Long X. A designed ZnO@ZIF-8 core-shell nanorod film as a gas sensor with excellent selectivity for H2 over CO. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23(33):7969–7975. doi: 10.1002/chem.201700320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chen EX, Yang H, Zhang J. Zeolitic imidazolate framework as formaldehyde gas sensor. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53(11):5411–5413. doi: 10.1021/ic500474j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chernikova V, Yassine O, Shekhah O, Eddaoudi M, Salama KN. Highly sensitive and selective SO2 MOF sensor: the integration of MFM-300 MOF as a sensitive layer on a capacitive interdigitated electrode. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6(14):5550–5554. doi: 10.1039/c7ta10538j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dou Z, Yu J, Cui Y, Yang Y, Wang Z, Yang D, Qian G. Luminescent metal–organic framework films as highly sensitive and fast-response oxygen sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136(15):5527–5530. doi: 10.1021/ja411224j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang J, Yue D, Xia T, Cui Y, Yang Y, Qian G. A luminescent metal–organic framework film fabricated on porous Al2O3 substrate for sensitive detecting ammonia. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017;253:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.06.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yassine O, Shekhah O, Assen AH, Belmabkhout Y, Salama KN, Eddaoudi M. H2S sensors: fumarate-based fcu-MOF thin film grown on a capacitive interdigitated electrode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55(51):15879–15883. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xu XY, Yan B. Intelligent molecular searcher from logic computing network based on Eu(III) functionalized UMOFs for environmental monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27(23):1700247. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201700247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang J, Dai Y, Zhu X, Wang Z, Li Y, Zhuang Q, Shi J, Gu J. Metal–organic frameworks with inherent recognition sites for selective phosphate sensing through their coordination-induced fluorescence enhancement effect. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3(14):7445–7452. doi: 10.1039/c5ta00077g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wu LL, Wang Z, Zhao SN, Meng X, Song XZ, Feng J, Song SY, Zhang HJ. A metal–organic framework/DNA hybrid system as a novel fluorescent biosensor for mercury(II) ion detection. Chem-Eur. J. 2016;22(2):477–480. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hao J, Liu FF, Liu N, Zeng ML, Song YH, Wang L. Ratiometric fluorescent detection of Cu2+ with carbon dots chelated Eu-based metal–organic frameworks. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017;245:641–647. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shi PF, Hu HC, Zhang ZY, Xiong G, Zhao B. Heterometal-organic frameworks as highly sensitive and highly selective luminescent probes to detect I− ions in aqueous solutions. Chem. Commun. 2015;51(19):3985–3988. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09081k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hao JN, Yan B. A water-stable lanthanide-functionalized MOF as a highly selective and sensitive fluorescent probe for Cd2+ Chem. Commun. 2015;51(36):7737–7740. doi: 10.1039/c5cc01430a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ma DX, Li BY, Zhou XJ, Zhou Q, Liu K, Zeng G, Li GH, Shi Z, Feng SH. A dual functional MOF as a luminescent sensor for quantitatively detecting the concentration of nitrobenzene and temperature. Chem. Commun. 2013;49(79):8964–8966. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44546a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yu Y, Ma JP, Zhao CW, Yang J, Zhang XM, Liu QK, Dong YB. Copper(I) metal–organic framework: visual sensor for detecting small polar aliphatic volatile organic compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2015;54(24):11590–11592. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang Y, Wu YC, Xie J, Hu XY. Metal–organic framework modified carbon paste electrode for lead sensor. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2013;177:1161–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2012.12.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yang J, Yang LT, Ye HL, Zhao FQ, Zeng BZ. Highly dispersed AuPd alloy nanoparticles immobilized on UiO-66-NH2 metal–organic framework for the detection of nitrite. Electrochim. Acta. 2016;219:647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.10.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jin JC, Wu J, Yang GP, Wu YL, Wang YY. A microporous anionic metal–organic framework for a highly selective and sensitive electrochemical sensor of Cu2+ ions. Chem. Commun. 2016;52(54):8475–8478. doi: 10.1039/c6cc03063g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]