Abstract

The worldwide trend of limiting the use of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) in animal production creates challenges for the animal feed industry, thus necessitating the development of effective non‐antibiotic alternatives to improve animal performance. Increasing evidence has shown that the growth‐promoting effect of AGPs is highly correlated with the reduced activity of bile salt hydrolase (BSH, EC 3.5.1.24), an intestinal bacteria‐producing enzyme that has a negative impact on host fat digestion and energy harvest. Therefore, BSH inhibitors may become novel, attractive alternatives to AGPs. Detailed knowledge of BSH substrate preferences and the wealth of structural data on BSHs provide a solid foundation for rationally tailored BSH inhibitor design. This review focuses on the relationship between structure and function of BSHs based on the crystal structure, kinetic data, molecular docking and comparative structural analyses. The molecular basis for BSH substrate recognition is also discussed. Finally, recent advances and future prospectives in the development of potent, safe, and cost‐effective BSH inhibitors are described.

Keywords: bile salt hydrolase, antibiotic growth promoters, fat digestion, structural basis for the substrate preference, BSH inhibitors, animal feed supplements

Abbreviations

- AGP

antibiotic growth promoter

- BSH

bile salt hydrolase

- CBAH

conjugated bile acid hydrolase

- CBSH

conjugated bile salt hydrolase

- CGH

cholylglycine hydrolase

- GC

preference for glyco‐conjugated bile acids

- GCA

glycocholic acid

- GCDCA

glycochenodeoxycholic acid

- GDCA

glycodeoxycholic acid

- MW

molecular weight

- Ntn

N‐terminal nucleophilic

- SDR

substrate‐preference determining residue

- TC

preferential hydrolysis of tauro‐conjugated bile acids

- TC/GC

equal hydrolysis of both tauro‐ and glyco‐conjugated bile acids

- TCA

taurocholic acid

- TCDCA

taurochenodeoxycholic acid

- TDCA

taurodeoxycholic acid

Introduction

Antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs), a group of antibiotics used in subtherapeutic quantities, have been used as feed additives to improve average daily weight gain and feed conversion ratio in food animals since the 1950s.1, 2 Although the benefits of this long‐established technique to growth promotion are still evident, recent epidemiological studies strongly indicate that AGPs exert selection pressure for the emergence, persistence, and transmission of antibiotic resistant bacteria, raising food safety, and public health concerns.2, 3 For this reason, there is a global trend to restrict the use of AGPs as additives in the feed industry,1, 2, 4 which necessitates the need to develop effective alternatives to AGPs to maintain productivity and sustainability of food animals.

Understanding the mechanism of how AGPs exert their growth‐promoting effects is critical for developing novel and effective AGP alternatives. It is widely accepted that AGPs mediate enhanced growth performance by altering intestinal microbial diversity and creating bacterial shifts.5 Although the definitive gut microbial community required for AGP‐mediated optimal growth promotion is still largely unknown, previous animal studies6, 7, 8, 9 have shown that the growth‐promoting effects of AGPs in pigs and chickens are highly and inversely correlated with the decreased activity of bile salt hydrolase (BSH, EC 3.5.1.24), an enzyme produced by various commensal bacteria in the intestine.1, 10

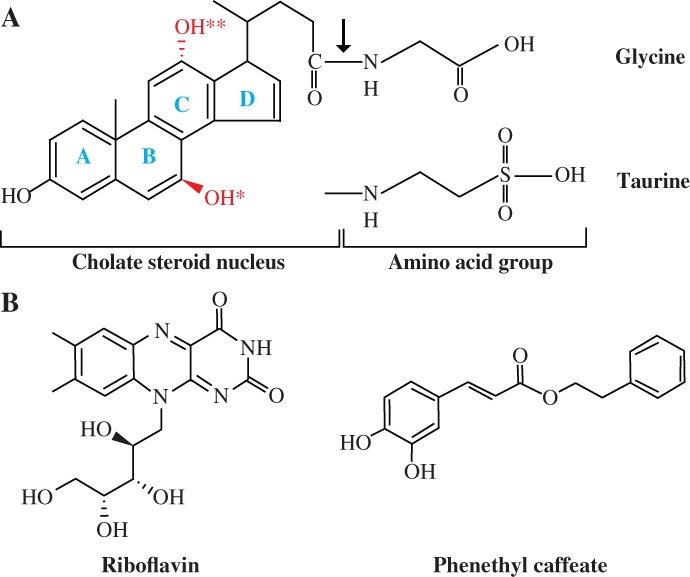

BSH, also called conjugated BSH (CBSH),11 conjugated bile acid hydrolase (CBAH)12 and cholylglycine hydrolase (CGH),13 is an enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of glycine‐ and/or taurine‐conjugated bile acids into deconjugated bile acids and amino acid residues [Fig. 1(A)].14 It belongs to N‐terminal nucleophilic (Ntn) hydrolase family. The microbial role of BSH activity and its impact on the host have been reviewed extensively.10, 15, 16 Although BSH enzymes confer BSH‐inactive bacterial resistance to bile acids,17, 18, 19 help fight against giardiasis,20, 21 and significantly reduce the serum cholesterol levels in pigs,22 dogs,23 mice24, 25 as well as humans,26, 27 they also have many negative effects on the host, such as dysfunctional lipid metabolism. Conjugated bile acids, synthesized from dietary cholesterol in the liver, are composed of a hydrophobic steroid core that is conjugated with either glycine or taurine [Fig. 1(A)].28 Their amphipathic characteristics make them more efficient “biological detergents” than unconjugated bile acids to emulsify and solubilize dietary lipids for fat digestion in the small intestine.10 Deconjugation of bile acids by BSHs from gut bacteria, therefore, leads to lipid malabsorption, which may cause weight loss of the host.10, 29 On the contrary, inhibiting the activities of intestinal BSHs will enhance lipid metabolism and energy harvest, thus improving growth performance and feed efficiency in food animals.

Figure 1.

Structures of a variety of substrates and inhibitors of BSHs. (A) General structures of bile acids. As an example, the structure of glycocholic acid is shown. The bond hydrolyzed by BSH is indicated by an arrow; rings A to D are highlighted in blue; OH* and OH** represent hydroxyl groups absent in deoxycholic and chenodeoxycholic acids, respectively. (B) Structures of BSH inhibitors riboflavin and phenethyl caffeate.

Recently, many BSH inhibitors have been developed to enhance animal growth performance and production. Copper and zinc which inhibit the activity of BSH are proved to improve the growth performance of swine9, 30 and poultry31, 32 as well as feed efficiency. Several BSH inhibitory compounds with potential as alternatives to AGPs, for example, two outstanding compounds riboflavin and phenethyl caffeate [Fig. 1(B)], have also been identified by an efficient high‐throughput screening system.5 Substrate‐guided rational development of inhibitors is another promising strategy.33, 34, 35 To facilitate the successful discovery and design of potent, safe and cost‐effective BSH inhibitors, however, a prerequisite is the detailed understanding of the molecular basis of BSH catalysis and substrate preference. In this review, genetic and biochemical properties of various BSHs, especially substrate preferences, are discussed. The current understanding of substrate recognition mechanism and structural basis for the substrate preferences of BSHs are then described. Finally, current progress and future prospects in BSH inhibitors development are highlighted.

Distribution of Bile Acids and BSHs

There are six main conjugated bile acids in bile, including taurocholic acid (TCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), glycocholic acid (GCA), glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), and glycochenodeoxycholic acid (GCDCA) [Fig. 1(A)]. Their abundance differs in various animals and humans. In chicken, the dominant bile acids present in the intestine are taurine conjugates TCDCA and TCA.6, 36 However, pigs mainly contain GCDCA, TCDCA, GCA, TCA, hyodeoxycholic, and hyocholic acids.36 The contents of conjugated bile acids in human are as follows: 9% TCA, 9% TDCA, 8% TCDCA, 26% GCA, 22% GDCA, and 26% GCDCA.37 Thus, the ratio of glycine to taurine conjugates is approximately 3:1.10, 38

BSH enzymes have been identified from commensal gut microbiota, pathogen, and free‐living bacteria.39 Most of them are detected in several genera of gastrointestinal autochthonous micro‐organisms in animals, including Bifidobacterium,40 Lactobacillus,41, 42 Enterococcus, 43 and Streptococcus.44 Among these bacteria, lactobacilli constitute an important aspect of the animal intestinal microbiota and contribute to the majority of the total BSH activity in vivo.45 Species of human intestinal archaea such as Methanosphaera stadmanae and Methanobrevibacter smithii are shown to produce BSHs.39 Certain pathogens like Brucella abortus,46 Listeria monocytogenes, 47 and Clostridium perfringens 48 have also been reported to encode BSHs. Brucella abortus 46 and opportunistic pathogens from Xanthomonas 49, 50 and Bacteroides genera51, 52 are the only Gram‐negative bacteria reported to exhibit BSH activity. Interestingly, free‐living bacteria isolated from hot water springs (Brevibacillus sp.),53, 54 Antarctic lakes (Planococcus antarticus),55 and marine sediments (Methanosarcina acetivorans)55 are also BSH positive.

Biochemical Properties and Substrate Preferences of BSHs

Nair et al.13 partially purified, for the first time, the BSH from C. perfringens ATCC 19574 in 1967, which is now commercially available (Sigma‐Aldrich Co., Chicago, IL). Since then, many BSH enzymes have been genetically and biochemically characterized. Among them, a total of 33 BSHs whose amino acid sequences and substrate preferences have been simultaneously reported are summarized in Table 1. As shown in this table, BSH enzymes from various sources differ in the number of amino acids, optimal pHs and temperatures, molecular weights (MWs), and substrate preferences. These BSHs are mainly intracellular enzymes56 encoded by 314–338 aa, with optimum pHs ranging from 3.8 to 7.0. Except for LjPF01_BSHC, whose optimum temperature is 70°C, most BSH enzymes identified act optimally at temperatures of 30–55°C. MWs of BSH subunits range from 34 to 42 kDa, while the native enzymes have MWs of 80–250 kDa. Most BSHs are homotetramers, with LaCRL1098_BSH, BlBB536_BSH, and BSH from B. fragilis ssp. fragilis ATCC 2528552 existing in homodimeric, homohexameric, and homooctameric forms, respectively. In addition, the four BSHs from Lactobacillus johnsonii 100–100 are homo‐ or heterotrimers.57, 58, 59 The occurrence of multiple forms of BSHs has also been observed in other strains such as two BSH homologs in L. salivarius LGM1447660 and L. acidophilus NCFM,28 three and four homologs in L. johnsonii PF0161, 62 and L. plantarum,41, 42, 63 respectively.

Table 1.

Biochemical Properties of All BSHs with Reported Amino Acid Sequences and Substrate Preferences from Various Micro‐organisms

| MW (kDa) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSH enzymea | Strain | Amino acids | GenBank accession no. | Optimum pH | Optimum temperature (°C) | Substrate preference b | Subunit | Native | References |

| LsUCC118_BSH1 | L. salivarius UCC118 | 316 | ACL98201.1 | 6.5 | —c | GC | 35.7 | — | 100 |

| LsJCM1046_BSH1 | L. salivarius JCM1046 | 324 | ACL98194.1 | 5.5 | — | TC | 36.5 | — | 100 |

| LsLGM14476_BSH1 | L. salivarius LGM14476 | 324 | ACL98197.1 | 5.5–7.0 | — | TC | 36.0 | 140 | 60 |

| LsLGM14476_BSH2 | L. salivarius LGM14476 | 325 | ACL98205.1 | 5.5–6.0 | — | TC/GC | 36.0 | 142 | 60 |

| LsB‐30514_BSH1 | L. salivarius B‐30514 | 324 | AFP87505.1 | 5.5 | 41 | GC | 37.0 | 85 | |

| LpBBE7_BSH | L. plantarum BBE7 | 324 | 6.0 | 37 | GC | 37.0 | 140–150 | 101, 102 | |

| LpST‐III_BSH1 | L. plantarum subsp. plantarum ST‐III | 324 | ADO00098.1 | — | — | GC | 37.0 | — | 42 |

| Lp80_BSH | L. plantarum 80 | 324 | AAB24746.1 | 4.7–5.5 | 30–45 | GC | 37.0 | 103 | |

| LpWCFS1_BSH1 | L. plantarum WCFS1 | 324 | CAD65617.1 | — | — | GC | 37.0 | — | 41 |

| LpCGMCC8198_BSH2 | L. plantarum CGMCC 8198 | 338 | AGG13403.1 | — | — | GC | 37.5 | — | 63 |

| LpCGMCC8198_BSH3 | L. plantarum CGMCC 8198 | 328 | AGG13404.1 | — | — | TC/GC | 36.1 | — | 63 |

| LpCGMCC8198_BSH4 | L. plantarum CGMCC 8198 | 317 | AGG13405.1 | — | — | TC | 35.7 | — | 63 |

| LgAM1_BSH | L. gasseri Am1 | 325 | FJ439777.1 | — | — | GC | 36.2 | — | 37 |

| LgFR4_BSH | L. gasseri FR4 | 326 | WP_020806888.1 | 5.5 | 52 | GC | 37.0 | — | 82 |

| LaNCFM_BSHA | L. acidophilus NCFM | 325 | AAV42751.1 | — | — | GC | 37.1 | — | 28 |

| LaNCFM_BSHB | L. acidophilus NCFM | 325 | AAV42923.1 | — | — | TC/GC | 37.0 | — | 28 |

| LrCRL1098_BSH | L. reuteri CRL 1098 | 325 | WP_035157795.1 | 5.2 | 37–45 | GC | 36.1 | 80 | 65, 104 |

| LjPF01_BSHA | L. johnsonii PF01 | 326 | EGP12224.1 | 5.0 | 55 | TC | 36.6 | — | 61 |

| LjPF01_BSHB | L. johnsonii PF01 | 316 | EF536029.1 | 6.0 | 40 | TC | 34.0 | — | 61, 62 |

| LjPF01_BSHC | L. johnsonii PF01 | 325 | EGP12391.1 | 5.0 | 70 | GC | 36.4 | — | 61 |

| Lj100–100_CBSHα | L. johnsonii 100–100 | 326 | AAG22541.1 | 3.8–4.5 | — | TC/GC | 42.0 | 115 | 57, 58, 59 |

| Lj100–100_CBSHβ | L. johnsonii 100–100 | 316 | AAC34381.1 | 3.8–4.5 | — | TC/GC | 38.0 | 105 | 57, 58, 59 |

| LfNCDO394_BSH | L. fermentum NCDO394 | 325 | AEZ06356.1 | 6.0 | 37 | GC | 36.5 | — | 105 |

| LrE9_BSH | L. rhamnosus E9 | 338 | ANQ47241.1 | — | — | GC | 37.1 | — | 106 |

| BlSBT2928_BSH | B. longum SBT2928 | 317 | AAF67801.1 | 5.0–7.0 | 40 | GC | 35.0 | 125–130 | 72, 75 |

| BlBB536_BSH | B. longum BB536 | 317 | 5.5–6.5 | 42 | TC/GC | 40.0 | 250 | 14, 107 | |

| BlLMG21814_BSH | B. longum subsp. suis LMG 21814 | 317 | KFI71781.1 | 5.0 | 37 | GC | 35.0 | 107–124 | 108 |

| BbATCC11863_BSH | B. bifidum ATCC 11863 | 316 | AAR39435.1 | — | — | GC | 35.0 | 140–150 | 40, 76 |

| BaBi30_BSH | B. animalis subsp. lactis Bi30 | 314 | AEK27050.1 | 4.7–6.5 | 50 | GC | 35.0 | 120–140 | 109 |

| BaKL612_BSH | B. animalis subsp. Lactis KL612 | 314 | AAS98803.1 | 6.0 | 37 | GC | 35.0 | — | 110, 111 |

| BpDSM20438_BSH | B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438 | 316 | KFI75916.1 | 5.0 | 37 | TC/GC | 35.0 | 123–154 | 108 |

| Cp13_CBAH1 | C. perfringens 13 | 329 | P54965.3 | 4.5 | — | TC | 36.1 | 147 | 48, 71 |

| EfNCIM2403_BSH | Enterococcus faecalis NCIM 2403 | 324 | EET97240.1 | 5.0 | 50 | TC | 37.0 | 140 | 77, 83 |

BSH, bile salt hydrolase; CBSH, conjugated bile salt hydrolase; CBAH, conjugated bile acid hydrolase.

TC, preferential hydrolysis of tauro‐conjugated bile acids; GC, preference for glyco‐conjugated bile acids; TC/GC, equal hydrolysis of both tauro‐ and glyco‐conjugated bile acids.

Not available.

Substrate preferences of BSHs listed in Table 1 were mostly determined by their kinetic parameters and specific activities toward different substrates. Most BSH enzymes characterized prefer to hydrolyze glyco‐conjugated bile acids (Table 1), which can be mainly ascribed to the steric hindrance caused by the sulfur atom in tauro‐conjugated bile acids [Fig. 1(A)].64 Because glyco‐conjugated bile acids are far more toxic for bacteria than the tauro‐conjugates, the higher affinity of BSHs for glyco‐conjugates may be of great importance in the ecology of gut microbe.37, 65 Seven BSH enzymes preferentially hydrolyze tauro‐conjugates, whereas other seven BSHs hydrolyze both glyco‐ and tauro‐conjugated bile acids, displaying a broad spectrum of specificity.

Most BSHs from L. johnsonii are more efficient at hydrolyzing tauro‐conjugated bile acids compared with glyco‐conjugates, although some exceptions are found. But the majority of BSH enzymes from L. plantarum and Bifidobacteria display preferential hydrolysis of glyco‐conjugated bile acids. Thus, the substrate preferences of BSHs may be strain dependent. In addition, multiple BSH homologues from the same strain may show different preferential activities such as LjPF01_BSHA, LjPF01_BSHB, and LjPF01_BSHC, exhibiting specific affinities for tauro‐, tauro‐, and glyco‐conjugated bile acids, respectively.61, 62

Potential Mechanism of Substrate Recognition

Despite the remarkable progress in identification and characterization of new BSHs, the molecular basis by which BSHs distinguish and recognize the two kinds of substrates remains unknown. Substrates of BSH enzymes consist of a cholate steroid nucleus and amino acid groups (glycine/taurine) [Fig. 1(A)]. Huijghebaert and Hofmann66 demonstrated that modification of amide bond or loss of a negative charge on the terminal group of an amino‐acid moiety of the bile acids greatly reduced the hydrolysis rate compared with glycine and taurine conjugates. Batta et al.67 showed that cholylglycine hydrolase was more efficient at hydrolyzing conjugates prepared from unconjugated bile acids and analogs of glycine and taurine with one or two methylene groups, but conjugates containing analogs of glycine and taurine with a tertiary amide group completely resisted hydrolysis. Most kinetic data available in the literature also indicate that substrates are predominantly recognized by BSHs at the amino acid moieties, and most BSHs prefer glyco‐conjugated bile acids over tauro‐conjugated ones.68, 69 But there is some evidence to suggest that modifications in the steroid ring system and the side chains affect the substrate preferences of BSH enzymes.28, 67, 70 It is, therefore, possible that BSHs have evolved to recognize bile acids on both the amino acid groups and cholate steroid nucleus. However, Batta et al.67 and Rossocha et al.71 reported that hydroxyl or epimerized hydroxyl substituents of cholate had no effect on the affinities of BSH enzymes and that the cholate was bound via hydrophobic interactions instead of hydrogen bonding, which complicates the identification of recognition sites. Thus, it appears that there are perhaps no specific binding conditions, except that the amino acids and cholate moieties should fit properly and are complementary to the substrate‐binding pockets.72

Structural Basis for the Substrate Preference of BSHs

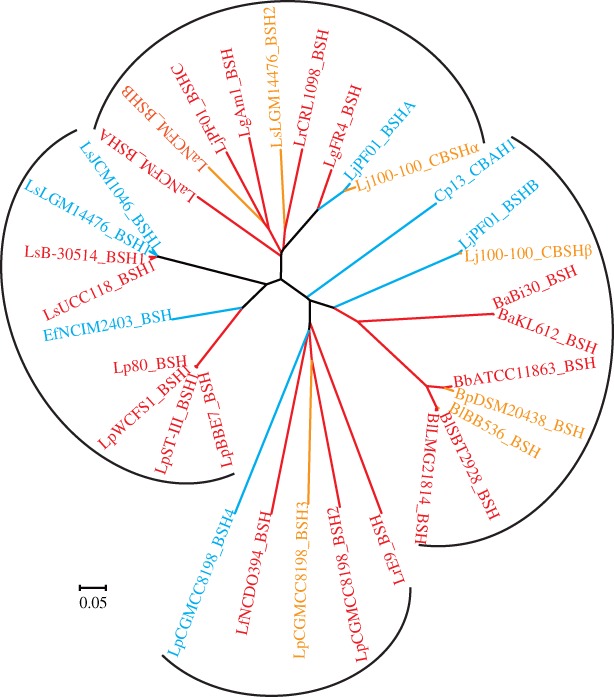

Phylogenetic clustering using Clustal X2 and MEGA 4.0 (Fig. 2) was employed to uncover the evolutionary distance of BSH enzymes listed in Table 1. This phylogenetic tree reveals the divergence among genetic characteristics of these BSHs. BSH enzymes from various bacteria are clearly divided into four groups (Fig. 2). Members of each group share a recent ancestor and have shorter genetic distances. However, in each group, BSHs exhibit different substrate preferences, which may be because evolution tends to broaden substrate selectivity.37 Multiple sequence alignment shows that the pairwise sequence identity of these BSHs ranges from 20.33% to 99.69%, with an average of 40.88%. BSH enzymes from L. johnsonii PF01 and L. johnsonii 100–100 have a high degree of similarities to those from other species, such as L. acidophilus and L. plantarum, because they are acquired through horizontal gene transfer.10, 28, 57 However, LjPF01_BSHC seems to be common only among L. johnsonii strains.61

Figure 2.

Family tree of BSH members with characterized substrate preference. BSHs exhibiting a preference for glyco‐ and tauro‐conjugated bile salts are highlighted by red and blue, respectively; while BSHs equally hydrolyzing both tauro‐ and glyco‐conjugated bile salts are colored in orange.

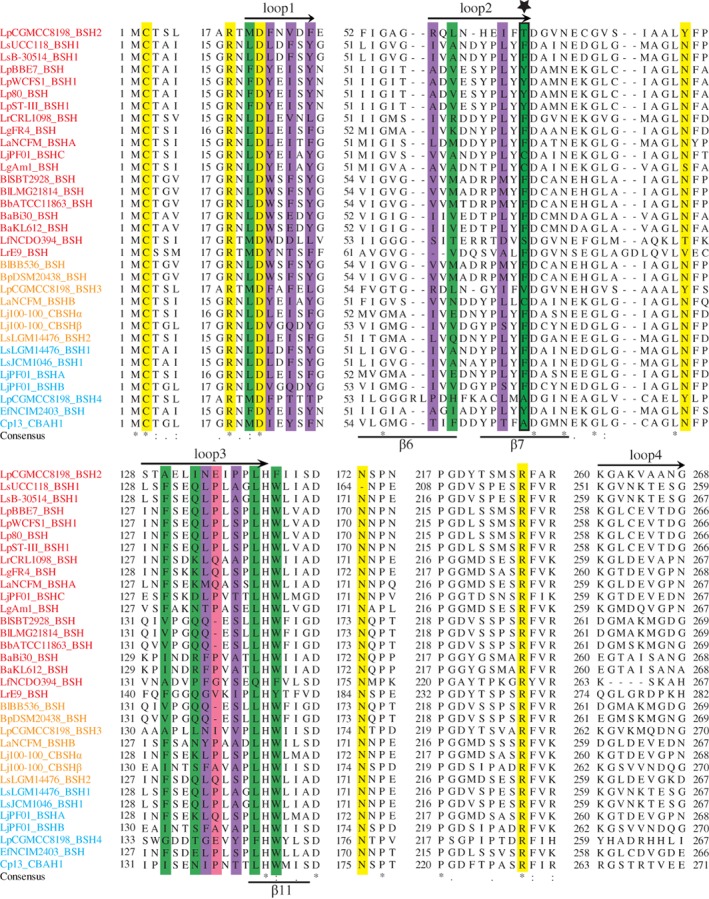

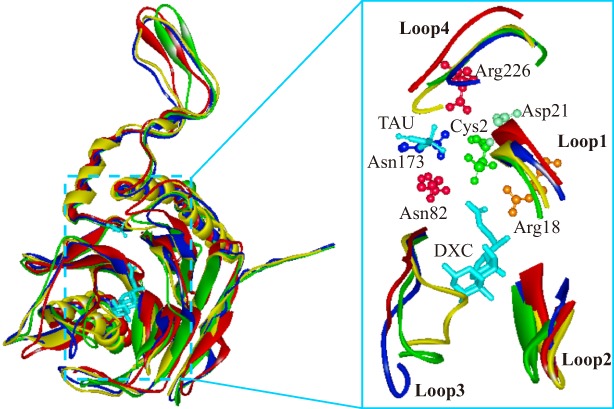

BSH enzymes catalyze amide bond hydrolysis through their N‐terminal nucleophile residue, Cys2 (unless otherwise stated, all the residues are numbered from methionine in BlSBT2928_BSH in this review), which is activated by autocatalytic endoproteolytic process to form a free α‐amino group serving as a base in the catalytic reaction.73 Aside from Cys2, other residues involved in the catalytic reaction, such as Arg18, Asp21, Asn82, Asn173, and Arg226, are also strictly conserved in BSHs (Fig. 3),62, 72 except the lack of Asn173 in LsUCC118_BSH1. The catalytic mechanism of BSHs involves an initial nucleophilic attack of Cys2 on the amide bond, followed by the formation of a tetrahedral intermediate which is stabilized by an oxyanion hole formed by the peptide NH of Asn82 and Asn173 Nδ2.71, 73, 74 In this process, Arg18 stabilizes the negatively charged sulfhydryl group of Cys2, while the N‐terminal Cys2 forms the catalytic Ntn‐diad with Asp21.64, 71 Asn173 (corresponding to Asn175 in Cp13_CBAH1) participates in substrate recognition via hydrogen bonding,74 whereas Arg226 (equivalent to Arg228 in Cp13_CBAH1) helps in transition‐state stabilization.74 Among these six active sites, however, Cys2 and Asn82 (corresponding to Asn79 in EfNCIM2403_BSH) are the only two residues whose essential roles in BSH activity have been confirmed by site‐directed mutagenesis.72, 75, 76, 77

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of BSHs listed in Table 1. BSHs with substrate preference for GC, TC/GC, and TC are colored in red, orange, and blue, respectively. Active sides are highlighted by yellow. Key amino acid residues potentially involved in substrate selectivity of Cp13_CBAH1, BlSBT2928_BSH, and LgFR4_BSH are highlighted by green, purple, and pink, respectively. Residues at Position 68 are indicated by a five‐pointed star. Secondary structure elements of BlSBT2928_BSH (above) and Cp13_CBAH1 (below) are also shown.

As enzymes possessing similar residues in their binding pockets may have similar mechanisms of action,78 substrate preference of BSHs may rely on specific amino acids (also called substrate‐preference determining residues, SDRs) and secondary structural elements.79 Recently, some key amino acid residues and secondary structural elements that are potentially involved in substrate binding have been identified in BSHs by binding site similarity‐based scoring system, crystal structure, kinetic data, molecular docking, and comparative structural analyses and are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 3. Except for Trp143, the 14 residues involved in substrate binding are located in three loops: Loop1 (20–26), Loop2 (59–68), and Loop3 (131–142). But no key residues have been reported in Loop4 (261–269). In the BSHs included in Figure 3, their substrate‐binding residues are not strongly conserved, except for Leu141 and Trp143, consistent with the previous findings.10, 72 Besides, Trp143 has been shown to be crucial for substrate binding in BlSBT2928_BSH.72, 80 However, most substitutions are conservative. The four loops of BSHs are predominantly hydrophobic. As compared with BSHs with substrate preference for TC/GC and TC, glyco‐conjugating‐specific BSHs have the lowest percentage of hydrophobic amino acids in their four loops, while the percentage of hydrophilic amino acids or charged amino acids in the four loops of these BSHs is the highest. These findings indicate that BSH enzymes may recognize their substrates through hydrophobic interactions with the hydrophobic steroid moiety.12, 71

Table 2.

Key Amino‐Acid Residues and Secondary Structural Elements that are Potentially Involved in Determining Substrate Preference

| BSH enzymea | Residue | Secondary structural element | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cp13_CBAH1 | Met20, Phe26, Phe61, Ala68, Ile133, Ile137, Leu142, and W144 | β6 (54–61), β7 (64–72), and β11 (142–147) | Crystal structure analysis | 61, 71, 72, 112 |

| BlSBT2928_BSH | Trp21 | Loops20–27, 35–50, 60–65, and 125–144 | Crystal structure and kinetic data analyses | 72 |

| BlSBT2928_BSH | Leu20, Trp22, Phe24, Tyr26, Val59, Met61, Met66, Phe68, Val133, Q137, Ser139, and Leu141 | Loop1 (20–26), Loop2 (59–68), and Loop3 (133–142) | Comparative structural analysis | 12 |

| BlSBT2928_BSH | — b | Loop1 (22–27), Loop2 (58–65), Loop3 (129–139), and Loop4 (261–269) | Binding site similarity‐based scoring system | 55 |

| LsB‐30514_BSH1 | Leu18, Phe22, Tyr24, Ile 56, Leu63, Phe65, Phe130, and Leu134 | Loop1 (20–27) and Loop2 (125–139) | Crystal structure analysis | 81 |

| LgFR4_BSH | Cys2, Phe25, Lys59, and Gln135 | — | Molecular docking analysis | 82 |

| EfNCIM2403_BSH | Phe18, Tyr20, and Tyr65 | Loop1 (21–25), Loop2 (57–64), Loop3 (125–137), and Loop4 (255–269) | Molecular docking analysis | 77 |

| BSH of L. plantarum PYPR1 | Leu6, Ile8, Asn12, Lys88, and Asp126 | — | Molecular docking analysis | 84 |

BSH, bile salt hydrolase; CBAH, conjugated bile acid hydrolase.

—, not available

Position 68 has been shown to be a potential substrate preference determining site in the crystal structure of Cp13_CBAH1,71 and it is noted due to its conservation of a non‐polar residue (alanine, phenylalanine, and valine) in BSHs with preference for tauro‐conjugated bile acids or a polar residue (tyrosine, cysteine, threonine, and serine) for glyco‐conjugating‐specific BSHs (Fig. 3).61 Because Ala68 in Cp13_CBAH1 (equivalent to Phe68 in BlSBT2928_BSH) is located within the valeric acid side chain of deoxycholate which is near the hydroxyl substituents, more hydrophilic amino acids added here can, therefore, alter the affinities toward the corresponding substrates.71 Ala68 also appears to have close interaction with the β11 sheet, which is significant for substrate binding and catalysis in Ntn‐hydrolases owing to its position within the αββα core structure.73 As shown in Figure 3, however, there are still 11 BSHs, for example, LsUCC118_BSH1, LsB‐30514_BSH1, LrCRL1098_BSH, LgFR4_BSH, and LaNCFM_BSHA, that have nonpolar residue phenylalanine at Position 68 but preferentially hydrolyze glyco‐conjugated bile acids. This may be because the residue at Position 68 is just one of many SDRs that determine the substrate preferences of BSH enzymes.

Other potential SDRs have also been identified in different BSHs (Table 2). In Cp13_CBAH1, it is found that deoxycholate is sandwiched by Phe61 and Ile137 on the side of the deoxycholyl ring A [Fig. 1(A)] and by Met20, Phe26, and Ala68 on the side of valeric acid side chain of deoxycholate. Additional important hydrophobic interactions are observed between deoxycholyl Ring B and Ile133 and between Ring D and Leu142.71 By substrate binding studies and sequence alignment, Trp22 in BlSBT2928_BSH is shown to play a selective role in the binding of bile acids and penicillin V.72 Based on comparative structural analysis, Phe130 and Leu134 are found to condense the substrate‐binding pocket entrance of LsB‐30514_BSH1 to restraint the spatial configuration, while Tyr24 and Phe65 may force the substrate to sit deeply in its binding pocket.81 Being located at the bottom of the binding pocket, Ile56 and Leu63 may determine the differing substrate preferences of LsB‐30514_BSH1. According to the results of molecular docking studies, Cys2 and Lys59 in the substrate‐binding pocket of LgFR4_BSH are found to form hydrogen bonds with GCA.82 Similarly, GDCA forms hydrogen‐bonding interactions with Cys2, Phe25, and Lys59, but Lys59 and Gln135 interact with TCA via hydrogen bonding. The three aromatic residues (Phe18, Tyr20, and Tyr65) of the binding pocket in EfNCIM2403_BSH, which are different from the corresponding residues in other BSHs, are shown to interact with the cholate part of GCA.77 Besides, they may also contribute to the higher activity and unique allosteric behavior of EfNCIM2403_BSH.83 In BSH from L. plantarum PYPR1, Leu6, Ile8, and Asn12 are also shown by molecular docking analysis to interact with TCA through hydrogen bonding, while Lys88 and Asp126 form hydrogen bonds with GCA.84 Since the amino acid sequence of L. plantarum PYPR1 BSH is not available now, these important residues are not highlighted in Figure 3.

To date, little information is available regarding the structural basis for BSHs function. Three‐dimensional structures of the BSH enzymes from only four species, C. perfringens (2bjf, Cp13_CBAH1),71 B. longum (2hez, BlSBT2928_BSH),72 L. salivarius (5hke, LsB‐30514_BSH),81 and E. faecalis (4wl3, EfNCIM2403_BSH),77 have been reported. A superimposition of the three‐dimensional structures of these four BSHs shows that they possess the distinctly conserved αββα tetra‐lamellar tertiary structures of Ntn hydrolase superfamily and that they share the conserved catalytic active center containing the cysteine nucleophile (Cys2) and its co‐ordinated neighboring amino acids (Fig. 4).71, 72 However, the substrate‐binding loops flanking the active site (Loops1–4) are variable. These loops not only determine the mode of substrate binding but also define the volume of the site. As compared with the corresponding loops of penicillin V acylase, the loops in BSHs are generally shorter to accommodate the bulky steroid nucleus in the active site.64 Subtle changes in these loop structures significantly affect the catalytic specificity of BSHs.12 Out of the four loops in BSHs, Loop3 (131–142) and Loop4 (261–269) show significant differences in terms of their conformation and folding (Fig. 4). Loop3 which interacts with the cholate backbone and contains more polar residues is also dynamic in BSHs, with different sizes and orientations.64 Besides, the third loops of Cp13_CBAH1 and EfNCIM2403_BSH which have higher affinities for tauro‐conjugates are more close to deoxycholic acid than those of BlSBT2928_BSH and LsB‐30514_BSH1, consequently reducing the size of the substrate‐binding pocket. As compared with other BSHs, the Loop2 of EfNCIM2403_BSH, part of the adduct binding site (Site A), is more extended, which might increase its dynamicity and flexibility and facilitate fast shuttling of the substrate and quick adduct release.77

Figure 4.

Comparison of the binding pocket loops of Cp13_CBAH1 (green; PDB ID: 2bjf), BlSBT2928_BSH (red; PDB ID: 2hez), LsB‐30514_BSH (yellow; PDB ID: 5hke), and EfNCIM2403_BSH (blue; PDB ID: 4wl3). TAU, taurine; DXC, deoxycholic acid. The six residues (Cys2, Arg18, Asp21, Asn82, Asn173, and Arg226) involved in the catalytic reaction in BlSBT2928_BSH are shown.

Polar complementarity toward the conjugated bile acids also constitutes an important factor influencing substrate preferences and catalytic framework of BSHs.55, 67 In BlSBT2928_BSH and EfNCIM2403_BSH, polar complementarity, along with good hydrogen bonding interactions, was observed for all three hydroxyl groups of GCA. As compared with BlSBT2928_BSH, the lower polar complementarity of Cp13_CBAH1 contributes to its lower enzyme activity.55, 72 A more in‐depth understanding of the structural changes and polar complementarity that occur during substrate binding would provide a new insight into the varied substrate preferences and functions of BSHs.

BSH Inhibitor Development

As noted above, BSH has been proposed as a key mechanistic microbiome target for developing novel alternatives to AGPs, and several BSH inhibitors have recently been developed. Copper (CuCl2) and zinc (ZnSO4) which can inhibit 98.1% and 89.5% of the activities of glyco‐conjugating‐specific LsB‐30514_BSH1, respectively, have been identified as potent BSH inhibitors.85 When used at high concentrations, they can improve the growth performance and feed efficiency in swine9, 30 and poultry.31, 32 Some currently used AGPs such as penicillin V, ampicillin, doxycycline hydrochloride,82 and tetracycline5 also show significant inhibitory effects on BSH activities. However, long‐term use of these metal ions and antibiotics affects animal health, and increases the accumulation of metal ions in the treated animals and the environment as well as the risk of acquiring antibiotic‐resistant bacteria, respectively. Recently, Smith et al. identified several promising BSH inhibitors from 2240 diverse compounds by an efficient high‐throughput system. Among them, riboflavin and phenethyl caffeate [Fig. 1(B)] not only display relatively higher inhibitory effects on LsB‐30514_BSH15 but can also inhibit the activities of LgFR4_BSH82 and LjPF01_BSHB86 which show a preference for glycol‐ and tauro‐conjugated bile acids, respectively. The mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of riboflavin was further unraveled by molecular docking analysis, which showed that both substrate and inhibitors (riboflavin and penicillin V) could bind to the substrate‐binding pocket of LgFR4_BSH with almost the same binding affinity/energy. It has also been shown that dietary supplementation with riboflavin (20 mg/kg feed) significantly enhances the feed efficiency and body weight in pigs.87 Additionally, riboflavin along with the probiotic L. gasseri FR4 can also serve as a BSH inhibitor.82 Because of its positive effects on animal physiology, riboflavin, a non‐toxic available reagent, has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of United States of America for the use as a feed additive to overcome vitamin B2 deficiencies in animals.5, 88

Although BSH inhibitors have been shown to improve the feed efficiency and growth performance of food animals, the precise mechanism behind their enhancing effects is yet to be delineated. Aside from their significant roles in lipid digestion, bile acids also function as versatile signaling molecules regulating cellular and metabolic activities such as their own synthesis and circulation, as well as glucose, triglyceride, cholesterol, and energy homeostasis.38, 64 Besides, as conjugated bile acids are toxic to bacteria, alteration of bile acid profiles caused by BSH hydrolysis may change gastrointestinal microbiota, which has been associated with metabolic diseases, for example, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia in animals and Type 2 diabetes mellitus and inflammatory bowel disease in humans.38, 64, 89 Therefore, further comprehensive animal trials are still needed to determine the precise mechanism underlying the enhancing effects of BSH inhibitors, especially the potential unexpected effects of BSH inhibitors such as excess fat deposition, disturbance of digestive microbiota, and changes in metabolism.

Concluding Remarks and Perspectives

Microbiome studies have shown that usage of AGPs does coincide with reduced BSH activity and decreased the population of some Lactobacillus species, the major BSH producer, in the intestine of food animals. Consequently, BSH has become a promising mechanistic microbiome target for developing novel alternatives to AGPs to enhance the productivity and sustainability of food animals. Although several BSH inhibitors have been identified by biochemical characterization and high‐throughput screening, the more detailed understanding of the structural basis for substrate preferences of BSHs would lay a solid foundation for the rationally tailoring of potent, safe, and cost‐effective BSH inhibitors.

As summarized in this review, structure analyses of BSH enzymes from various species reveal critical residues in catalysis and provide key information on substrate selectivity of BSHs. However, research on the substrate preference determinants of BSHs is still in its infancy. Future in‐depth structural analysis of BSHs in complex with specific substrates and inhibitors, along with comprehensive amino acid substitution mutagenesis would help to discover SDRs and understand the structural basis for the substrate preferences of BSHs.90 As both BSH and penicillin V acylase belong to Ntn hydrolases superfamily, the SDRs identified in penicillin V acylase may also affect the substrate preferences of BSH. Recently, based on the concept that the binding specificity would covary with SDRs, some structure‐driven computational and theoretical approaches have been developed for SDRs identification, including likelihood methods,91 independence tests,92 information theoretic approaches,93 Bayesian methods,94 and statistical coupling analysis.95 The basic idea is to search two sites in a multiple sequence alignment, or a pair of multiple sequence alignments that exhibit reciprocal changes when studying protein–protein interactions. Among these methods, the information theoretic approach which uses sequence information only without known crystal structure has been successfully used for the identification of SDRs in many protein recognition domains such as PDZ,96 SH3,97 and kinase domains.98 This makes information theoretic approach a good candidate for the precise identification of preference determinants of BSH enzymes in further studies.

As a close relative of BSHs, β‐lactamase (also known as penicillinase, EC 3.5.2.6) also acts on amide bonds, lessons learned from discovering or designing β‐lactamase inhibitors can also be applied to the development of BSH inhibitors. The important factors that must be taken into consideration when designing BSH inhibitors may include99 (i) exhibiting high affinity for the active site of the target enzyme; (ii) mimicking the “natural substrate” (substrate analogues); (iii) stabilizing interactions in the active site; (iv) rapid cell penetration. As BSHs are mainly in the intracellular space of bacteria, the rapidity with which inhibitors can access their target is a requisite for successful inhibition; (v) low propensity to induce BSH production; (vi) the risk of bacterial adaption to BSH inhibitors.

With the increased knowledge on the substrate preferences of BSHs and the role of BSH‐producing bacteria, it should be possible to tailor BSH inhibitors‐based feed additives to replace AGPs in the future. Such inhibitors could also be used in conjunction with probiotics to design rationally tailored dietary supplements that will enhance animal health and performance. Large animal trials are also highly warranted to determine the effects of these feed additives on the growth performance of food animals.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported by the Youth Innovation Fund from Tianjin University of Science & Technology(Grant No. 2016LG15).

References

- 1. Dibner JJ, Richards JD (2005) Antibiotic growth promoters in agriculture: history and mode of action. Poult Sci 84:634–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marshall BM, Levy SB (2011) Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:718–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wegener HC (2003) Antibiotics in animal feed and their role in resistance development. Curr Opin Microbiol 6:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaskins HR, Collier CT, Anderson DB (2002) Antibiotics as growth promotants: mode of action. Anim Biotechnol 13:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith K, Zeng XM, Lin J (2014) Discovery of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors using an efficient high‐throughput screening system. PLoS One 9:e85344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knarreborg A, Lauridsen C, Engberg RM, Jensen SK (2004) Dietary antibiotic growth promoters enhance the bioavailability of alpha‐tocopheryl acetate in broilers by altering lipid absorption. J Nutr 134:1487–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guban J, Korver DR, Allison GE, Tannock GW (2006) Relationship of dietary antimicrobial drug administration with broiler performance, decreased population levels of Lactobacillus salivarius, and reduced bile salt deconjugation in the ileum of broiler chickens. Poult Sci 85:2186–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dumonceaux TJ, Hill JE, Hemmingsen SM, Van Kessel AG (2006) Characterization of intestinal microbiota and response to dietary virginiamycin supplementation in the broiler chicken. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2815–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacela JY, Derouchey JM, Tokach MD, Goodband RD, Nelssen JL, Renter DG, Dritz SS (2011) Feed additives for swine: fact sheets – high dietary levels of copper and zinc for young pigs, and phytase. Anim Sci Abroad 18:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CG (2006) Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1729–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar RS, Brannigan JA, Pundle A, Prabhune A, Dodson GG, Suresh CG (2004) Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X‐ray diffraction analysis of conjugated bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium longum . Acta Cryst D60:1665–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lambert JM, Siezen RJ, De Vos WM, Kleerebezem M (2008) Improved annotation of conjugated bile acid hydrolase superfamily members in Gram‐positive bacteria. Microbiology 154:2492–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nair P, Gordon M, Reback J (1967) The enzymatic cleavage of the carbon‐nitrogen bond in 3α, 7α, 12α‐trihydroxy‐5β‐cholan‐24‐oylglycine. J Biol Chem 242:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grill J, Schneider F, Crociani J, Ballongue J (1995) Purification and characterization of conjugated bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium longum BB536. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:2577–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel AK, Singhania RR, Pandey A, Chincholkar SB (2009) Probiotic bile salt hydrolase: current developments and perspectives. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 162:166–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones ML, Tomaro‐Duchesneau C, Martoni CJ, Prakash S (2013) Cholesterol lowering with bile salt hydrolase‐active probiotic bacteria, mechanism of action, clinical evidence, and future direction for heart health applications. Expert Opin Biol Th 13:631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho SK, Lee SJ, Shin SY, Moon JS, Li L, Joo W, Kang DK, Han NS (2015) Development of bile salt‐resistant Leuconostoc citreum by expression of bile salt hydrolase gene. J Microbiol Biotechnol 25:2100–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiong ZQ, Wang QH, Kong LH, Song X, Wang GQ, Xia YJ, Zhang H, Sun Y, Ai LZ (2017) Short communication: improving the activity of bile salt hydrolases in Lactobacillus casei based on in silico molecular docking and heterologous expression. J Dairy Sci 100:975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang G, Yin S, An H, Chen S, Hao Y (2010) Coexpression of bile salt hydrolase gene and catalase gene remarkably improves oxidative stress and bile salt resistance in Lactobacillus casei . J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 38:985–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Travers MA, Sow C, Zirah S, Deregnaucourt C, Chaouch S, Queiroz RML, Charneau S, Allain T, Florent I, Grellier P (2016) Deconjugated bile salts produced by extracellular bile‐salt hydrolase‐like activities from the probiotic Lactobacillus johnsonii La1 inhibit Giardia duodenalis in vitro growth. Front Microbiol 7:1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allain T, Chaouch S, Thomas M, Travers MA, Valle I, Langella P, Grellier P, Polack B, Florent I, Bermudez‐Humaran LG (2018) Bile salt hydrolase activities: a novel target to screen anti‐giardia Lactobacilli? Front Microbiol 9:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park YH, Kim JG, Shin YW, Kim HS, Kim YJ, Chun T, Kim SH, Whang KY (2008) Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus 43121 and a mixture of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium longum on the serum cholesterol level and fecal sterol excretion in hypercholesterolemia‐induced pigs. Biosci Biotech Bioch 72:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strompfová V, Marciňáková M, Simonová M, Bogovič‐Matijašić B, Lauková A (2006) Application of potential probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum AD1 strain in healthy dogs. Anaerobe 12:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeun J, Kim S, Cho S‐Y, H‐j J, Park H‐J, Seo J‐G, Chung M‐J, Lee S‐J (2010) Hypocholesterolemic effects of Lactobacillus plantarum KCTC3928 by increased bile acid excretion in C57BL/6 mice. Nutrition 26:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liong MT, Shah NP (2005) Bile salt deconjugation ability, bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol co‐precipitation ability of Lactobacilli strains. Int Dairy J 15:391–398. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martoni CJ, Labbe A, Ganopolsky JG, Prakash S, Jones ML (2015) Changes in bile acids, FGF‐19 and sterol absorption in response to bile salt hydrolase active L. reuteri NCIMB 30242. Gut Microbes 6:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones M, Martoni C, Parent M, Prakash S (2012) Cholesterol‐lowering efficacy of a microencapsulated bile salt hydrolase‐active Lactobacillus reuteri NCIMB 30242 yoghurt formulation in hypercholesterolaemic adults. Br J Nutr 107:1505–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McAuliffe O, Cano RJ, Klaenhammer TR (2005) Genetic analysis of two bile salt hydrolase activities in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4925–4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, Bork P, Vos WMD (2016) Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre‐school children. Nat Commun 7:10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shelton NW, Tokach MD, Nelssen JL, Goodband RD, Dritz SS, DeRouchey JM, Hill GM (2011) Effects of copper sulfate, tri‐basic copper chloride, and zinc oxide on weanling pig performance. J Anim Sci 89:2440–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arias VJ, Koutsos EA (2006) Effects of copper source and level on intestinal physiology and growth of broiler chickens. Poult Sci 85:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu ZH, Lu L, Li SF, Zhang LY, Xi L, Zhang KY, Luo XG (2011) Effects of supplemental zinc source and level on growth performance, carcass traits, and meat quality of broilers. Poult Sci 90:1782–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang ZY (2002) Protein tyrosine phosphatases: structure and function, substrate specificity, and inhibitor development. Annu Rev Pharmacol 42:209–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swedberg JE, Nigon LV, Reid JC, de Veer SJ, Walpole CM, Stephens CR, Walsh TP, Takayama TK, Hooper JD, Clements JA, Buckle AM, Harris JM (2009) Substrate‐guided design of a potent and selective kallikrein‐related peptidase inhibitor for kallikrein 4. Chem Biol 16:633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clancy KW, Melvin JA, McCafferty DG (2010) Sortase transpeptidases: insights into mechanism, substrate specificity, and inhibition. Biopolymers 94:385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haslewood GA (1971) Bile salts of germ‐free domestic fowl and pigs. Biochem J 123:15–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang J, Hang X, Zhang M, Liu X, Li D, Yang H (2010) Diversity of bile salt hydrolase activities in different Lactobacilli toward human bile salts. Ann Microbiol 60:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Long SL, Gahan CGM, Joyce SA (2017) Interactions between gut bacteria and bile in health and disease. Mol Aspects Med 56:54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones BV, Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CG, Marchesi JR (2008) Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:13580–13585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim GB, Yi SH, Lee BH (2004) Purification and characterization of three different types of bile salt hydrolases from Bifidobacterium strains. J Dairy Sci 87:258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lambert JM, Bongers RS, de Vos WM, Kleerebezem M (2008) Functional analysis of four bile salt hydrolase and penicillin acylase family members in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:4719–4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ren J, Sun K, Wu Z, Yao J, Guo B (2011) All 4 bile salt hydrolase proteins are responsible for the hydrolysis activity in Lactobacillus plantarum ST‐III. J Food Sci 76:M622–M628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wijaya A, Hermann A, Abriouel H, Specht I, Yousif NMK, Holzapfel WH, Franz C (2004) Cloning of the bile salt hydrolase (bsh) gene from Enterococcus faecium FAIR‐E 345 and chromosomal location of bsh genes in food Enterococci . J Food Protect 67:2772–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lim HJ, Kim SY, Lee WK (2004) Isolation of cholesterol‐lowering lactic acid bacteria from human intestine for probiotic use. J Vet Sci 5:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kumar R, Grover S, Mohanty AK, Batish VK (2010) Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of bile salt hydrolase gene (bsh) from Lactobacillus plantarum MBUL90 strain of human origin. Food Biotechnol 24:215–226. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Delpino MV, Marchesini MI, Estein SM, Comerci DJ, Cassataro J, Fossati CA, Baldi PC (2007) A bile salt hydrolase of Brucella abortus contributes to the establishment of a successful infection through the oral route in mice. Infect Immun 75:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dussurget O, Cabanes D, Dehoux P, Lecuit M, Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Cossart P (2002) Listeria monocytogenes bile salt hydrolase is a PrfA‐regulated virulence factor involved in the intestinal and hepatic phases of listeriosis. Mol Microbiol 45:1095–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coleman JP, Hudson LL (1995) Cloning and characterization of a conjugated bile acid hydrolase gene from Clostridium perfringens . Appl Environ Microbiol 61:2514–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dean M, Cervellati C, Casanova E, Squerzanti M, Lanzara V, Medici A, Polverino de Laureto P, Bergamini CM (2002) Characterization of cholylglycine hydrolase from a bile‐adapted strain of Xanthomonas maltophilia and its application for quantitative hydrolysis of conjugated bile salts. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:3126–3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pedrini P, Andreotti E, Guerrini A, Dean M, Fantin G, Giovannini PP (2006) Xanthomonas maltophilia CBS 897.97 as a source of new 7β‐ and 7α‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases and cholylglycine hydrolase: improved biotransformations of bile acids. Steroids 71:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kawamoto K, Horibe I, Uchida K (1989) Purification and characterization of a new hydrolase for conjugated bile acids, chenodeoxycholyltaurine hydrolase, from Bacteroides vulgatus . J Biochem 106:1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stellwag EJ, Hylemon PB (1976) Purification and characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Bacteroides fragilis subsp. fragilis . Biochim Biophys Acta 452:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sridevi N, Prabhune AA (2009) Brevibacillus sp: a novel thermophilic source for the production of bile salt hydrolase. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 157:254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sridevi N, Srivastava S, Khan BM, Prabhune AA (2009) Characterization of the smallest dimeric bile salt hydrolase from a thermophile Brevibacillus sp. Extremophiles 13:363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Panigrahi P, Sule M, Sharma R, Ramasamy S, Suresh CG (2014) An improved method for specificity annotation shows a distinct evolutionary divergence among the microbial enzymes of the cholylglycine hydrolase family. Microbiol‐SGM 160:1162–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kim GB, Lee BH (2005) Biochemical and molecular insights into bile salt hydrolase in the gastrointestinal microflora‐a review. Asian‐Austral J Anim Sci 18:1505–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elkins CA, Moser SA, Savage DC (2001) Genes encoding bile salt hydrolases and conjugated bile salt transporters in Lactobacillus johnsonii 100‐100 and other Lactobacillus species. Microbiology 147:3403–3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lundeen SG, Savage DC (1990) Characterization and purification of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus sp. strain 100‐100. J Bacteriol 172:4171–4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lundeen SG, Savage DC (1992) Multiple forms of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus sp. strain 100‐100. J Bacteriol 174:7217–7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bi J, Fang F, Lu S, Du G, Chen J (2013) New insight into the catalytic properties of bile salt hydrolase. J Mol Catal B‐Enzym 96:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chae J, Valeriano V, Kim GB, Kang DK (2013) Molecular cloning, characterization and comparison of bile salt hydrolases from Lactobacillus johnsonii PF01. J Appl Microbiol 114:121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oh HK, Lee JY, Lim SJ, Kim MJ, Kim GB, Kim JH, Hong SK, Kang DK (2008) Molecular cloning and characterization of a bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus acidophilus PF01. J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gu XC, Luo XG, Wang CX, Ma DY, Wang Y, He YY, Li W, Zhou H, Zhang TC (2014) Cloning and analysis of bile salt hydrolase genes from Lactobacillus plantarum CGMCC No. 8198. Biotechnol Lett 36:975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chand D, Avinash VS, Yadav Y, Pundle AV, Suresh CG, Ramasamy S (2017) Molecular features of bile salt hydrolases and relevance in human health. BBA – General Subjects 1861:2981–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Taranto MP, Sesma F, Font de Valdez G (1999) Localization and primary characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus reuteri . Biotechnol Lett 21:935–938. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huijghebaert SM, Hofmann AF (1986) Influence of the amino acid moiety on deconjugation of bile acid amidates by cholylglycine hydrolase or human fecal cultures. J Lipid Res 27:742–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Batta AK, Salen G, Shefer S (1984) Substrate specificity of cholylglycine hydrolase for the hydrolysis of bile acid conjugates. J Biol Chem 259:15035–15039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Grill JP, Manginot‐Dürr C, Schneider F, Ballongue J (1995) Bifidobacteria and probiotic effects: action of Bifidobacterium species on conjugated bile salts. Curr Microbiol 31:23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ha CG, Cho JK, Chai YG, Ha Y, Shin SH (2006) Purification and characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus plantarum CK 102. J Microbiol Biotechnol 16:1047–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moser SA, Savage DC (2001) Bile salt hydrolase activity and resistance to toxicity of conjugated bile salts are unrelated properties in Lactobacilli . Appl Environ Microbiol 67:3476–3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rossocha M, Schultz‐Heienbrok R, von Moeller H, Coleman JP, Saengers W (2005) Conjugated bile acid hydrolase is a tetrameric N‐terminal thiol hydrolase with specific recognition of its cholyl but not of its tauryl product. Biochemistry 44:5739–5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kumar RS, Brannigan JA, Prabhune AA, Pundle AV, Dodson GG, Dodson EJ, Suresh CG (2006) Structural and functional analysis of a conjugated bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium longum reveals an evolutionary relationship with penicillin V acylase. J Biol Chem 281:32516–32525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Oinonen C, Rouvinen J (2000) Structural comparison of Ntn‐hydrolases. Protein Sci 9:2329–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lodola A, Branduardi D, De Vivo M, Capoferri L, Mor M, Piomelli D, Cavalli A (2012) A catalytic mechanism for cysteine N‐terminal nucleophile hydrolases, as revealed by free energy simulations. PLoS One 7:e32397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tanaka H, Hashiba H, Kok J, Mierau I (2000) Bile salt hydrolase of Bifidobacterium longum‐biochemical and genetic characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:2502–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim GB, Miyamoto CM, Meighen EA, Lee BH (2004) Cloning and characterization of the bile salt hydrolase genes (bsh) from Bifidobacterium bifidum strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5603–5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chand D, Panigrahi P, Varshney NK, Ramasamy S, Suresh CG (2018) Structure and function of a highly active bile salt hydrolase (BSH) from Enterococcus faecalis and post‐translational processing of BSH enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1866:507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Haupt VJ, Daminelli S, Schroeder M (2013) Drug promiscuity in PDB: protein binding site similarity is key. PLoS One 8:e65894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ruiz L, Margolles A, Sanchez B (2013) Bile resistance mechanisms in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium . Front Microbiol 4:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kumar RS, Suresh CG, Brannigan JA, Dodson GG, Gaikwad SM (2007) Bile salt hydrolase, the member of Ntn‐hydrolase family: differential modes of structural and functional transitions during denaturation. IUBMB Life 59:118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Xu FZ, Guo FF, Hu XJ, Lin J (2016) Crystal structure of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus salivarius . Acta Cryst F72:376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rani RP, Anandharaj M, Ravindran AD (2017) Characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus gasseri FR4 and demonstration of its substrate specificity and inhibitory mechanism using molecular docking analysis. Front Microbiol 8:1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chand D, Ramasamy S, Suresh CG (2016) A highly active bile salt hydrolase from Enterococcus faecalis shows positive cooperative kinetics. Process Biochem 51:263–269. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yadav R, Singh PK, Puniya AK, Shukla P (2017) Catalytic interactions and molecular docking of bile salt hydrolase (BSH) from L. plantarum RYPR1 and its prebiotic utilization. Front Microbiol 7:2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wang Z, Zeng X, Mo Y, Smith K, Guo Y, Lin J (2012) Identification and characterization of a bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus salivarius for development of novel alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:8795–8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lin J, Negga R, Zeng X, Smith K (2014) Effect of bile salt hydrolase inhibitors on a bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus acidophilus . Pathogens 3:947–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Stahly TS, Williams NH, Lutz TR, Ewan RC, Swenson SG (2007) Dietary B vitamin needs of strains of pigs with high and moderate lean growth. J Anim Sci 85:188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gutierrez‐Preciado A, Torres AG, Merino E, Bonomi HR, Goldbaum FA, Garcia‐Angulo VA (2015) Extensive identification of bacterial riboflavin transporters and their distribution across bacterial species. PLoS One 10:e0126124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Islam KB, Fukiya S, Hagio M, Fujii N, Ishizuka S, Ooka T, Ogura Y, Hayashi T, Yokota A (2012) Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. Gastroenterology 141:1773–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Yip KY, Utz L, Sitwell S, Hu XH, Sidhu SS, Turk BE, Gerstein M, Kim PM (2011) Identification of specificity determining residues in peptide recognition domains using an information theoretic approach applied to large‐scale binding maps. BMC Biol 9:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dekker JP, Fodor A, Aldrich RW, Yellen G (2004) A perturbation‐based method for calculating explicit likelihood of evolutionary co‐variance in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20:1565–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Galitsky B (2003) Revealing the set of mutually correlated positions for the protein families of immunoglobulin fold. In Silico Biol 3:241–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Martin LC, Gloor GB, Dunn SD, Wahl LM (2005) Using information theory to search for co‐evolving residues in proteins. Bioinformatics 21:4116–4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dimmic MW, Hubisz MJ, Bustamante CD, Nielsen R (2005) Detecting coevolving amino acid sites using Bayesian mutational mapping. Bioinformatics 21:I126–I135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shulman AI, Larson C, Mangelsdorf DJ, Ranganathan R (2004) Structural determinants of allosteric ligand activation in RXR heterodimers. Cell 116:417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Tonikian R, Zhang YN, Sazinsky SL, Currell B, Yeh JH, Reva B, Held HA, Appleton BA, Evangelista M, Wu Y, Xin XF, Chan AC, Seshagiri S, Lasky LA, Sander C, Boone C, Bader GD, Sidhu SS (2008) A specificity map for the PDZ domain family. Plos Biol 6:2043–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Tonikian R, Xin XF, Toret CP, Gfeller D, Landgraf C, Panni S, Paoluzi S, Castagnoli L, Currell B, Seshagiri S, Yu HY, Winsor B, Vidal M, Gerstein MB, Bader GD, Volkmer R, Cesareni G, Drubin DG, Kim PM, Sidhu SS, Boone C (2009) Bayesian modeling of the yeast SH3 domain interactome predicts spatiotemporal dynamics of endocytosis proteins. Plos Biol 7:e1000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mok J, Kim PM, Lam HYK, Piccirillo S, Zhou XQ, Jeschke GR, Sheridan DL, Parker SA, Desai V, Jwa M, Cameroni E, Niu HY, Good M, Remenyi A, Ma JLN, Sheu YJ, Sassi HE, Sopko R, Chan CSM, De Virgilio C, Hollingsworth NM, Lim WA, Stern DF, Stillman B, Andrews BJ, Gerstein MB, Snyder M, Turk BE (2010) Deciphering protein kinase specificity through large‐scale analysis of yeast phosphorylation site motifs. Sci Signal 3:ra12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Drawz SM, Bonomo RA (2010) Three decades of beta‐lactamase inhibitors. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:160–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Fang F, Li Y, Bumann M, Raftis EJ, Casey PG, Cooney JC, Walsh MA, O'Toole PW (2009) Allelic variation of bile salt hydrolase genes in Lactobacillus salivarius does not determine bile resistance levels. J Biotechnol 191:5743–5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Dong Z, Zhang J, Lee B, Li H, Du G, Chen J (2012) A bile salt hydrolase gene of Lactobacillus plantarum BBE7 with high cholesterol‐removing activity. Eur Food Res Technol 235:419–427. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Dong Z, Zhang J, Lee BH, Li H, Du G, Chen J (2013) Secretory expression and characterization of a bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus plantarum in Escherichia coli . J Mol Catal B‐Enzym 93:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Christiaens H, Leer RJ, Pouwels PH, Verstraete W (1992) Cloning and expression of a conjugated bile acid hydrolase gene from Lactobacillus plantarum by using a direct plate assay. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:3792–3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bustos AY, Font de Valdez G, Raya RR, Taranto MP (2016) Genetic characterization and gene expression of bile salt hydrolase (bsh) from Lactobacillus reuteri CRL 1098, a probiotic strain. Int J Genom Proteom Metabolom Bioinform 1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kumar R, Rajkumar H, Kumar M, Varikuti SR, Athimamula R, Shujauddin M, Ramagoni R, Kondapalli N (2013) Molecular cloning, characterization and heterologous expression of bile salt hydrolase (Bsh) from Lactobacillus fermentum NCDO394. Mol Biol Rep 40:5057–5066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kaya Y, Kok MS, Ozturk M (2017) Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Lactobacillus rhamnosus E9 strain. Food Biotechnol 31:128–140. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Shuhaimi M, Ali AM, Saleh NM, Yazid AM (2001) Cloning and sequence analysis of bile salt hydrolase (bsh) gene from Bifidobacterium longum . Biotechnol Lett 23:1775–1780. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Jarocki P, Podlesny M, Glibowski P, Targonski Z (2014) A new insight into the physiological role of bile salt hydrolase among intestinal bacteria from the genus Bifidobacterium . PLoS One 9:e114379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Piotr J (2011) Molecular characterization of bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bi30. J Microbiol Biotechnol 21:838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kim GB, Lee BH (2008) Genetic analysis of a bile salt hydrolase in Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis KL612. J Appl Microbiol 105:778–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Zhou X, Zhang J, Chen J, Du G (2016) Expression, purification and enzymatic properties study of the bile salt hydrolase from Bifidobacterium in Escherichia coli . J Food Sci Biotechnol 35:792–800. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Suresh CG, Pundle AV, SivaRaman H, Rao KN, Brannigan JA, McVey CE, Verma CS, Dauter Z, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG (1999) Penicillin V acylase crystal structure reveals new Ntn‐hydrolase family members. Nat Struct Biol 6:414–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]