Abstract

Data from recent studies support the hypothesis that infections by human gastrointestinal (GI) helminths impact, directly and/or indirectly, on the composition of the host gut microbial flora. However, to the best of our knowledge, these studies have been conducted in helminth-endemic areas with multi-helminth infections and/or in volunteers with underlying gut disorders. Therefore, in this study, we explore the impact of natural mono-infections by the human parasite Strongyloides stercoralis on the faecal microbiota and metabolic profiles of a cohort of human volunteers from a non-endemic area of northern Italy (S+), pre- and post-anthelmintic treatment, and compare the findings with data obtained from a cohort of uninfected controls from the same geographical area (S−). Analyses of bacterial 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing data revealed increased microbial alpha diversity and decreased beta diversity in the faecal microbial profiles of S+ subjects compared to S−. Furthermore, significant differences in the abundance of several bacterial taxa were observed between samples from S+ and S− subjects, and between S+ samples collected pre- and post-anthelmintic treatment. Faecal metabolite analysis detected marked increases in the abundance of selected amino acids in S+ subjects, and of short chain fatty acids in S− subjects. Overall, our work adds valuable knowledge to current understanding of parasite-microbiota associations and will assist future mechanistic studies aimed to unravel the causality of these relationships.

Subject terms: Statistical methods, Parasite host response

Introduction

The human gastrointestinal (GI) tract is inhabited by a myriad of bacteria, viruses, archaea, fungi, and other unicellular and multicellular microorganisms, that together form the gut micro- and macrobiota1–4. Whilst some members of the microbiota can cause severe disease5, most resident bacteria exert a number of specialised functions that are beneficial to the human host, including absorption of nutrients, synthesis of essential organic compounds, development of adaptive immunity and protection against pathogens6–9. Disturbances of the composition of the gut microbiota (i.e. dysbiosis) have been unequivocally linked to the onset of a range of gut and systemic diseases, such as chronic autoimmune and allergic disorders, obesity, diabetes and, more recently, multiple sclerosis (MS)10–13. On the other hand, with a few exceptions, multicellular organisms residing in the GI tract, such as parasitic worms (=helminths) are mostly considered detrimental to human health, as they can subtract nutrients, damage host tissues and release toxic waste products14–16. Nonetheless, in the developing world, infections by parasitic helminths have been associated with a low incidence of allergic and autoimmune diseases, as encompassed by the ‘hygiene hypothesis’17,18; this observation has led to the ‘curative’ properties of a range of GI helminths being investigated in a range of clinical trials aimed to develop novel therapeutics against selected chronic inflammatory disorders, such as ulcerative colitis19,20, Crohn’s disease21–24, coeliac disease25,26 and MS27–31. Whilst preliminary results from a number of such trials are promising, a thorough understanding of the mechanisms that determine the anti-inflammatory properties of these helminths is necessary to assist the development of new effective therapeutics against these disorders. These properties are predominantly attributed to the ability of parasites and/or their excretory/secretory products to modulate host immune responses to facilitate their long-term establishment in the human gut32–43; nevertheless, in recent years, the ability of controlled infections by selected GI helminths to ameliorate clinical signs of chronic inflammation has been hypothesized to stem, at least in part, from direct and/or immune-mediated interactions between parasites and the resident microbial flora (reviewed by44). This hypothesis is supported by observations from several studies45–50 that have reported associations between human infections by GI parasites (under experimental and natural settings) and shifts in the composition of the human gut microbiota towards a ‘healthy’ phenotype, as well as increased levels of metabolites with anti-inflammatory properties45–50. However, information reported to date have been derived from cohorts of human volunteers with underlying chronic gut disorders (e.g. coeliac disease45–48) or conditions of malnutrition and/or multi-specific helminth infections and/or exposed to multiple re-infections50–53, with likely implications on the ‘steady-state’ of the gut flora of these individuals. Whilst complete elimination of these confounding factors is difficult to achieve in human studies, investigations of the impact that infections by single species of GI helminths exert on the composition of the gut flora of individuals with no clinical evidence of concurring co-infections or underlying gut disorders may help disentangle the causality of parasite-microbiota relationships; in turn, this knowledge may assist the design of mechanistic experiments in available animal models of infection and disease (cf.54–57), aimed to achieve a better understanding of the therapeutic properties of parasites.

Strongyloides stercoralis is a soil transmitted intestinal nematode estimated to infect ~370 million people worldwide, with higher prevalence (ranging from 10% to 60%) recorded across tropical and subtropical regions58–61. The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex, in that it involves both free-living and parasitic adult stages58,62. In particular, the small intestine of the vertebrate hosts (e.g. humans) harbours adult females only, which reproduce via parthenogenesis and lay eggs that hatch immediately, releasing first stage rhabditiform larvae (L1s) that are excreted with the host faeces (reviewed by58,62). However, L1s can also develop into invasive filariform larvae that are able to re-infect the host without being excreted (i.e. ‘autoinfection’)62. Once in the environment, male L1s develop through four larval stages to free-living adults; conversely, female L1s can either develop through to free-living adults (similarly to males) or reach a developmental stage infective to a new susceptible host, i.e. the infective third-stage larva (L3). Importantly, the new generation of female parasites deriving from sexual reproduction of free-living males and females is inevitably parasitic58,62. These infective larvae typically infect humans percutaneously and migrate to the small intestine, where the cycle recommences58,62. Autoinfection of a susceptible host can occur at a low level for several years, and is often subclinical or asymptomatic58,62 although, in immunosuppressed individuals, parasites can spread to all organs and tissues causing (potentially fatal) ‘disseminated strongyloidiasis’.

Chronic infections by S. stercoralis provide a golden opportunity to evaluate the effect/s of long-term colonisation by parasitic nematodes on the composition of the human gut microbiota. In this study, we explore the impact of natural infections by S. stercoralis on the faecal microbiota and metabolic profiles of a cohort of elderly volunteers (with no clinical evidence of concurrent pathologies of infectious or non-infectious origin) from northern Italy. This area is non-endemic for parasitic nematodes, but characterised by the presence of sporadic cases of chronic infections by S. stercoralis in elderly individuals in which the parasite has persisted through several decades via autoinfection63. We profiled the faecal microbiota of these subjects pre- and post-anthelmintic treatment with ivermectin, and compared the findings with a control cohort of uninfected individuals from the same geographical area.

Results

The composition of the faecal microbiota of human volunteers infected by Strongyloides stercoralis pre- and post-anthelmintic treatment

Individual faecal samples were collected from 20 elderly volunteers [74 ± 11 years of age (average ± standard deviation)] with confirmed infections by S. stercoralis (S+), as well as from 11 uninfected volunteers (S−) of comparable age and from the same geographical areas (Supplementary Fig. S1). Additional faecal samples were collected from 13 (out of 20) S+ subjects 6 months post-anthelmintic treatment. In comparative analyses of the human faecal microbiota pre- and post-treatment, samples from the latter 13 subjects are hereafter referred to as S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment, respectively. A total of 44 faecal samples were subjected to microbial DNA extraction and high-throughput Illumina sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene [i.e. S+ = 20 (including S+pre-treatment = 13), S+post-treatment = 13 and S− = 11] whilst a total of 31 samples [i.e. S+ = 14 (including S+pre-treatment = 8), S+post-treatment = 7 and S− = 10] were subjected to metabolite profiling via nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (cf. Supplementary Table S1).

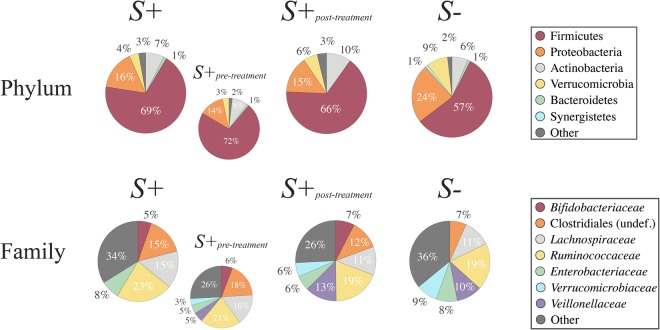

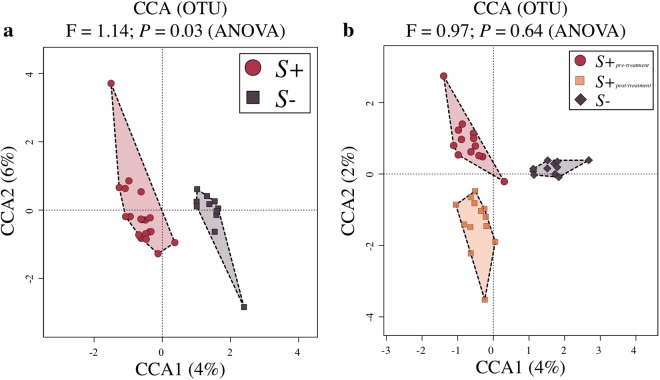

High-throughput amplicon sequencing yielded a total of 5,717,403 paired-end reads (not shown), of which 1,446,150 high-quality sequences (per sample mean 26,778 ± 13,928) were retained after quality control. Rarefaction curves generated following in silico subtraction of low-quality sequences indicated that the majority of faecal bacterial diversity was well represented by the sequence data (Supplementary Fig. S2). These sequences were assigned to 2,630 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and 15 bacterial phyla, respectively (data available from Mendeley Data at 10.17632/n86dtjvmbv.1). The phyla Firmicutes (64.5% average ± 14.4% standard deviation) and Proteobacteria (18.2 ± 12.8%) were most abundant in all samples analysed, followed by the phyla Actinobacteria (7.9 ± 6.4%), Verrucomicrobia (5.4 ± 7.7%) and Bacteroidetes (1 ± 1.1%) (Fig. 1). At the order level, Clostridiales were most abundant in all samples analysed (54.4 ± 15.2%), and included the two most abundant microbial families, i.e. the Ruminococcaceae (20.6 ± 11.6%) and the Lachnospiraceae (13.4 ± 8.1%) (Fig. 1). Faecal microbial community profiles were ordinated by Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) (Fig. 2a), that separated samples by infection status (S+ and S−) (effect size (F) = 1.14, P = 0.03). No statistically significant differences between the gut microbial composition of S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment, and S− subjects were detected (F = 0.97, P = 0.64; Fig. 2b). Similarly, S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment samples did not show any statistically significant difference in community composition (P > 0.05, CCA).

Figure 1.

Firmicutes and Proteobacteria are most abundant phyla in the faecal microbiota of all study subjects. Relative abundances of bacterial phyla and families detected in faecal samples from Strongyloides stercoralis infected and uninfected subjects (S+ and S−, respectively) and of the subset of S+ subjects that had received anthelmintic treatment (associated sub-circles), both prior to (S+pre-treatment) and 6 months post-ivermectin administration (S+post-treatment). Percentages in individual pie chart sections indicate the relative proportion of a given bacterial phylum or family.

Figure 2.

The faecal microbial profiles of Strongyloides stercoralis-infected individuals and uninfected controls. Differences between the faecal microbial profiles of S. stercoralis infected and uninfected subjects (S+ and S−, respectively) (a), and between the microbial profiles of the subset of S+ subjects that had received anthelmintic treatment, both prior to (S+pre-treatment) and 6 months post-ivermectin administration (S+post-treatment), and of S− subjects, ordinated by supervised Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA; b).

Infection by Strongyloides stercoralis is associated with increased alpha diversity, and decreased beta diversity, of the faecal microbiota

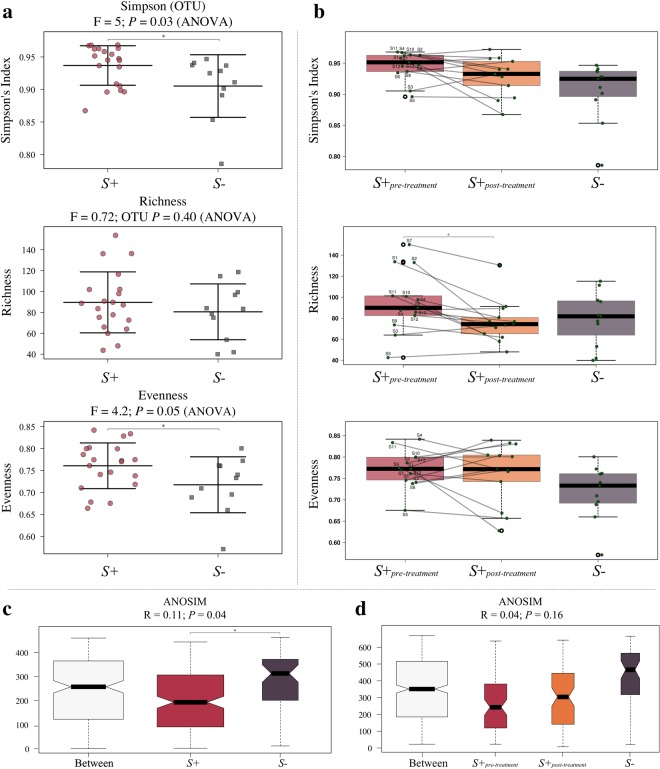

Microbial alpha diversity, measured through Simpson’s index, and evenness were significantly increased in the faecal microbiota of S+ volunteers when compared to that of S− (F = 5, P = 0.03 and F = 4.2, P = 0.05 respectively) (Fig. 3a). Faecal microbial richness was not significantly different between S+ and S− subjects, albeit a trend towards increased richness in samples from S+ subjects was observed. Simpson diversity and richness were decreased in samples from S+post-treatment compared to S+pre-treatment, although only the latter was significant (P < 0.001; mixed effect linear regression) (Fig. 3b). Compared to S−, S+post-treatment samples showed a trend towards increased Simpson diversity and evenness, while richness was lower in samples post-treatment when compared to samples from uninfected subjects (Fig. 3b). Microbial beta diversity was significantly lower in samples from S+ subjects when compared to S− subjects (effect size (R) = 0.11, P = 0.04; Fig. 3c), whilst beta diversity in S+post-treatment samples was higher than that in S+pre-treatment but lower than that in S− samples, albeit not significantly (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

The faecal microbiome of Strongyloides stercoralis-infected subjects is characterised by increased alpha diversity and decreased beta diversity, respectively, when compared to that of uninfected controls. (a) Differences in overall microbial Simpson (alpha) diversity, and corresponding richness and evenness, between the faecal microbial profiles of S. stercoralis-infected and uninfected subjects (S+ and S−, respectively), and (b) between the faecal microbial profiles of the subset of S+ subjects that had received anthelmintic treatment, both prior to (S+pre-treatment) and 6 months post-ivermectin administration (S+post-treatment), and of S− subjects. (c) Differences in microbial beta diversity between S+ and S− samples, as well as (d) between samples from S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment and S−. The bold and black horizontal lines in the boxplots refer to the respective mean (i.e. Simpson’s Index, richness, and evenness) associated with the corresponding group, with top and bottom whiskers representing the standard deviation. Points connected by lines in (b) refer to samples collected from the same study participant pre- and post-anthelmintic treatment. Significant differences between study groups are marked by an asterisk (*).

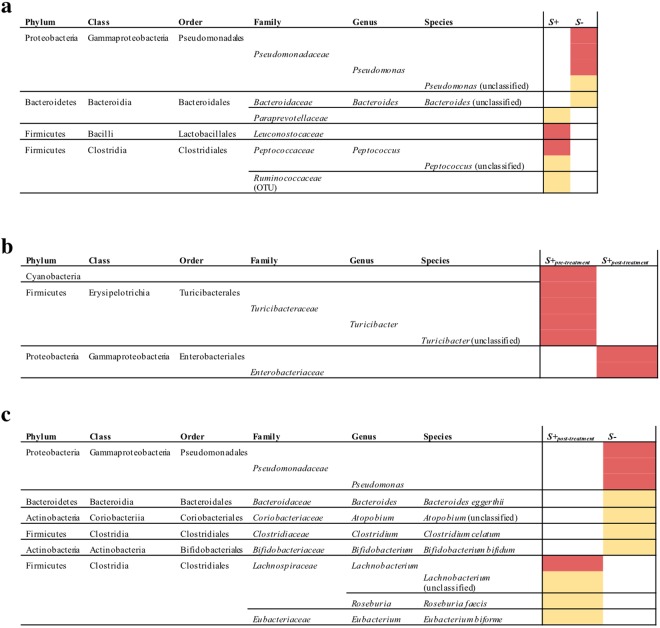

Strongyloides stercoralis infection is associated with expanded populations of Leuconostocaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Paraprevotellaceae and Peptococcus and reduced Pseudomonadales

Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) revealed significant differences in the abundance of individual microbial taxa (phylum to species level) between S+ and S− subjects (Fig. 4a). In particular, the faecal microbiota of S− subjects was significantly enriched for populations of bacteria belonging to the order Pseudomonadales (genus Pseudomonas) and an unidentified species belonging to the genus Bacteroides (Fig. 4a); conversely, bacteria belonging to the families Leuconostocaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Paraprevotellaceae and to the genus Peptococcus, amongst others, were significantly higher in the faecal microbiota of S+ subjects (Fig. 4a). In addition, in samples from S+post-treatment subjects, a significant decrease of bacteria belonging to the order Turicibacterales (genus Turicibacter) and an increase of Enterobacteriales (in particular associated to the genus Shigella) were observed compared to corresponding samples from S+pre-treatment (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. S3). Additionally, differences were observed between the microbial profiles of S+post-treatment samples when compared to S−, with the latter displaying increased levels of bacteria belonging to the order Pseudomonadales and genus Atopobium, as well as Bacteroides eggerthii, Clostridium celatum and Bifidobacterium bifidum, and decreased levels of Lachnobacterium, Roseburia faecis, and Eubacterium biforme, respectively (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Differentially abundant bacterial taxa in the faecal microbiota of Strongyloides stercoralis (a) infected and uninfected subjects (S+ and S−, respectively), (b) infected subjects pre- and post anthelmintic treatment with ivermectin (S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment, respectively), and (c) infected subjects post-anthelmintic treatment and uninfected subjects (S+post-treatment and S− respectively), based on Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis. Colours correspond to Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) scores of 4 or higher (red) and 3.5 to 4 (yellow).

The faecal metabolome of Strongyloides stercoralis infected volunteers is characterized by low levels of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and increased amino acid abundance

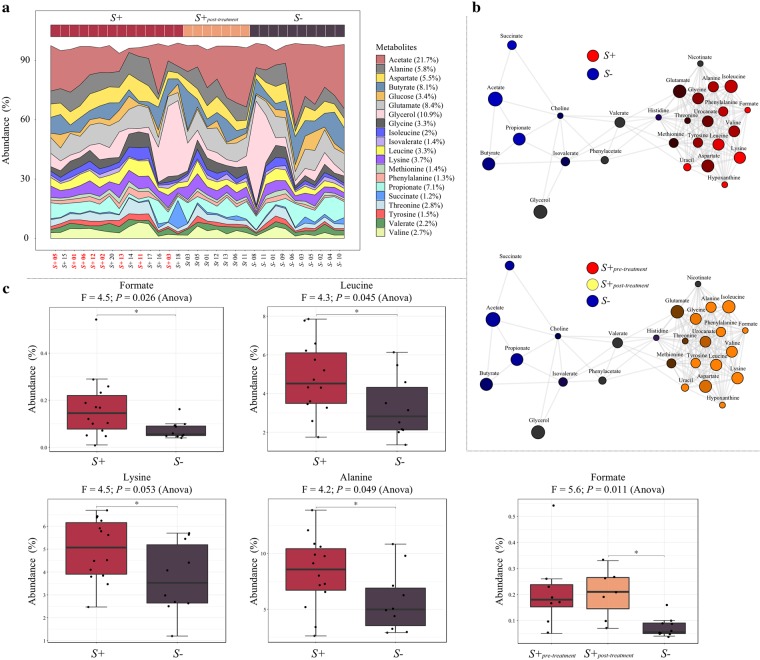

A total of 28 metabolites were identified by NMR across all samples (Fig. 5a); these were subjected to Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), which unveiled no marked differences in faecal metabolic profiles between samples from S+ and S− subjects, as well as from S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment, and S− subjects (data not shown). However, association network analysis of S+ and S− samples indicated clustering of several faecal metabolites according to the infection status of the study subjects. In particular, 13 metabolites (alanine, isoleucine, glycine, phenylalanine, formate, valine, tyrosine, leucine, lysine, uracil, hypoxanthine, and aspartate), were positively correlated with each other and associated with the faecal metabolic profiles of S+ subjects (Fig. 5b), whereas four (the SCFAs propionate, butyrate, and acetate, as well as succinate) were also positively correlated with each other, and associated with faecal samples from S− subjects (Fig. 5b). When applied to the faecal metabolic profiles of S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment and S− subjects, network analysis associated the 13 metabolites described above (previously associated with S+) with both S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment, whereas the SCFAs remained associated with the metabolic profiles of S− subjects (Fig. 5b). Analysis of differentially abundant metabolites between S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment, and S− samples via ANOVA further revealed that 10 (out of 12) metabolites associated with samples from S+post-treatment subjects were less abundant than in S+pre-treatment samples, but more abundant when compared to S− samples, albeit not significantly (Supplementary Fig. S4). Additionally, alanine, formate, lysine, and leucine were significantly more abundant in samples from S+ when compared to S− (F = 4.2, P = 0.05; F = 4.5, P = 0.03; F = 4.5, P = 0.05; F = 4.3, P = 0.05 respectively) whilst formate was significantly more abundant in S+post-treatment compared to S− subjects (F = 5.6, P = 0.01); nevertheless, these differences were not significant following p-value correction for multiple testing (FDR > 0.05) (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

Decreased levels of selected short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and increased levels of amino acids are associated with Strongyloides stercoralis infection. (a) Area plot indicating the abundance (expressed as percentage) of metabolites detected by nuclear magnetic resonance analysis (NMR) in faecal samples from S. stercoralis-infected and uninfected subjects (S+ in red, and S− in purple), as well as from the subset of S+ subjects that had received anthelmintic treatment, both prior to (S+pre-treatment, red sample label) and 6 months post-ivermectin administration (S+post-treatment, in orange). (b) Network analysis displaying associations between individual or clusters of metabolites and sample groups (i.e. S+ in red, S− in blue [top network], S+pre-treatment in red, S+post-treatment in yellow and S− in blue [bottom network]). For metabolites associated with multiple sample groups, the respective circle colours are mixed according to the strength of the association. (c) Differentially abundant metabolites detected in faecal samples from S+ and S−, as well as S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment, and S− subjects, determined using ANOVA. The bold and black horizontal lines in the boxplots refer to the mean of percentage abundance of metabolite associated with the corresponding group, with top and bottom whiskers representing the standard deviation. Significant differences between study groups are marked by an asterisk (*).

Using GC-MS, a total of 13 fatty acids were detected across all analysed faecal samples, including lauric acid (C12:0), myristic acid (C14:0), pentadecanoic acid (C15:0, C15:0 iso, and C15:0 ante), palmitic acid (C16:0), margaric acid (C17:0, C17:0 iso, C17:0 ante), stearic acid (C18:0), oleic acid (C18:1), linoleic acid (C18:2), and arachidic acid (C20:0) (Supplementary Fig. S5). No significant associations between any of the analysis groups were detected using PCoA and no significant differences in the relative abundance of individual metabolites were observed between samples from S+ and S− subjects, as well as S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment, and S− subjects (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to determine the effect/s that chronic, monospecific infections by the parasitic nematode S. stercoralis exert/s on the faecal microbiome and metabolome of human volunteers from a non-endemic area of Europe, and establish whether such effects are reversed following the administration of anthelmintic treatment. Whilst the overall composition of the faecal microbiota of Strongyloides-infected and uninfected volunteers enrolled in this study largely reflected that of human subjects harbouring GI helminths under natural or experimental conditions of infections described in previous investigations, the relatively low proportions of Bacteroidetes observed in our samples contrast findings from some previously published reports47,48,50,51,53. However, this discrepancy may be accounted for by differences in mean age of the cohorts enrolled in our (72 years of age) versus previous studies (i.e. 11–51 years of age; cf.47,48,50,51,53); indeed, a decline in the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in the gut microbiota of aging subjects has been documented in several studies64–67, and is thus considered ‘physiological’ in the age group enrolled in our experiment.

In spite of the overall similarities in the composition of the faecal microbiota of S+ and S− subjects at phylum level, CCA analysis revealed differences in the microbial profiles of these two groups, thus indicating that S. stercoralis infection was associated with shifts in the relative abundance of individual gut bacterial species. Indeed, microbial alpha diversity was significantly higher in the faecal microbiota of S+ when compared to S−. In particular, the level of microbial alpha diversity detected in the latter group largely reflected that recorded in a cohort of healthy, elderly Italians investigated previously68. Conversely, microbial beta diversity was significantly decreased in faecal samples from S+ subjects when compared to S−. Increased levels of microbial alpha diversity have been repeatedly observed in the gut microbiome of human subjects infected by a range of GI helminths (i.e. Necator americanus, Trichuris trichiura, and Ascaris sp.)47,48,50. Since alpha diversity measures are frequently used as proxy of microbiome ‘health’ (with high alpha diversity associated with a mature, homogenous, stable and healthy gut microbial environment69,70), it has been proposed that the direct or immune-mediated ability of GI helminths to restore gut homeostasis by promoting increases in microbial richness and evenness may represent one mechanism by which parasites exert their therapeutic properties in individuals with chronic inflammatory disorders48,49,71.

The difference in microbial alpha and beta diversity observed between S+ and S− subjects were determined by dissimilarities in the relative abundance of selected bacterial taxa in the faecal microbial profiles of these study groups. In particular, significantly expanded populations of Clostridia and Leuconostocaceae could be detected in the faecal microbiota of S+ when compared to S− subjects. Notably, selected strains of Clostridia strains have been identified as leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis, due to their roles in protecting the gut from pathogen colonisation, mediating host immune system development and modulating immunological tolerance72. On the other hand, members of the Leuconostocaceae, a family of anaerobic lactic acid-producing bacteria, have been demonstrated to stimulate the release of inflammatory Th1 type cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ by activated antigen-presenting cells in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, thus promoting the activation of antimicrobial immune responses73. However, a significant decrease in the abundance of Leuconostocaceae was recorded in the faecal microbiota of humans infected by hookworms, whipworms and ascarids51, contrasting findings from this study and highlighting the need for further investigations in this area. In addition, the lactobacilli, another group of lactic acid-producing bacteria that has been positively associated with parasite colonisation in rodent models of helminth infections in several recently published studies55,74–82, was not detected amongst the bacterial populations that were expanded in samples from S+ subjects. It must be also pointed out that, thus far and to the best of our knowledge, investigations conducted in human volunteers have not reported significant shifts in the abudance of lactobacilli in the gut microbiota of helminth-infected subjects45,47,48,50–53. Whilst expanded populations of lactobacilli following helminth colonisation may represent a rodent-specific response to infection, mechanistic studies conducted, for instance, in microbiota-humanised mouse models of helminth infections may assist clarifying this point.

The faecal microbiota of S− subjects was enriched with a number of known opportunistic and/or potentially pathogenic bacteria, including Bacteroides eggerthii (higher abundances of which have been linked to increased risk for and severity of colitis in mice83) and species within the genus Pseudomonas. Expanded populations of opportunistic and potentially pathogenic microbes, coupled with an overall increase in bacterial beta diversity, have been described in the microbiome of aging humans84,85 and may therefore underpin our observations.

Notably, whilst administration of ivermectin (a macrocyclic lactone) to a sub-group of S+ subjects did not result in significant differences in the levels of microbial alpha- and beta diversity post-anthelmintic treatment (likely due to the limited number of volunteers who agreed to provide further faecal samples 6 months post-treatment), a tendency towards decreased alpha diversity and increased beta diversity, respectively, was observed in S+post-treatment samples when compared to S+pre-treatment. Nevertheless, an increase in pathogenic bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae (linked to the genus Shigella) was observed in samples from S+post-treatment subjects when compared to S+pre-treatment. This change was also accompanied by an increase in the probiotic Lachnospiraceae in S+post-treatment subjects when compared to S−86, thus suggesting that anthelmintic treatment may have affected the taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota of previously infected subjects. Conversely, a recent study investigating the impact of treatment with albendazole (a benzimidazole compound) on a large cohort of human volunteers from Indonesia infected by ascarids, whipworms and/or hookworms, detected no differences between the faecal microbial composition of these volunteers and that of a placebo-treated cohort87. This discrepancy may be attributable to fundamental differences between the two anthelmintics investigated and/or between parasite species assessed, and/or to sample size limitations; nevertheless, future experiments carried out in large cohorts of volunteers and/or in experimental models of Strongyloides infection (i.e. rodents infected by Strongyloides ratti) may provide further clarification.

In this study, besides determining the qualitative and quantitative composition of the gut microbiota of Strongyloides-infected human volunteers, we also carried out, for the first time in helminth-infected individuals, a comprehensive analysis of the faecal metabolome of the same subjects. Indeed, given that perturbations of the gut microbiota homeostasis are known to exert downstream effects on intestinal metabolism88,89, we hypothesized that alterations in gut microbial profiles associated to colonisation by S. stercoralis might be accompanied by changes in the relative abundance of individual metabolites in faecal samples, with potential implications for the overall health of infected individuals. Whilst analysis via NMR and GC-MS revealed no significant differences in the relative abundance of the vast majority of metabolites identified in samples from S+ versus S−, a number of amino acids (i.e. leucine, lysine, and alanine) were significantly more abundant in the faecal metabolome of infected individuals when compared to the uninfected cohort. Notably, anthelmintic treatment appeared to only affect the metabolites associated with helminth infection, i.e. amino acids, and thus may suggest that the helminth removal affects both the microbiome and the metabolome. An increased abundance of amino acids in the predicted faecal metabolome of helminth infected-subjects had been previously reported, albeit this information had been indirectly inferred from high-throughput metagenomics sequencing data50,90. Amino acids play key roles in the maintenance of the gut microbiome homeostasis and metabolism, since they support the growth and survival of bacteria in the GI tract91. Simultaneously, the gut microbiome exerts important functions in the metabolism of alimentary and endogenous proteins that are converted into peptides and amino acids92,93. In particular, the most prevalent species involved in amino acid fermentation within the human intestine are bacteria belonging to the class Clostridia94–96, that were more abundant in the faecal microbiota of S+ subjects. Of the amino acids that were significantly more abundant in the faecal metabolome of S+ subjects, lysine and leucine participate in biological pathways that are key to the maintenance of the gut homeostasis97,98. In addition, the biological functions of lysine and leucine are closely linked99, suggesting a possible correlation with the positive association of both these amino acids with the faecal metabolome of Strongyloides-infected subjects.

In contrast with the increased quantities of amino acids observed in the faecal metabolome of S+ subjects, the SCFAs acetate, propionate, and butyrate were significantly less abundant in this group compared to S−. This observation contradicts findings from a previous study in which these SCFAs were increased in faecal samples from human volunteers with coeliac disease and experimentally infected with the human hookworm, N. americanus49. Given the known anti-inflammatory properties of SCFAs, Zaiss et al.49 had hypothesized that these molecules may play a role in the therapeutic effects of GI helminths in chronic inflammatory disorders. The discrepancy observed between our study and that by Zaiss et al.49 may be attributable to differences between the cohorts of human volunteers investigated (acutely vs. chronically infected; middle aged vs. aged), species of parasite under consideration and infection burden (known vs. unknown). In addition, both studies are characterised limited sample sizes that may have contributed to these contrasting results.

In summary, in our study, monospecific, chronic S. stercoralis infections were associated with global shifts in the composition of the human faecal microbiota, as well as subtle changes in the faecal metabolic profiles of these individuals when compared with those of uninfected control subjects. In addition, anthelmintic treatment resulted in minor alterations of the faecal microbiota and metabolome of these volunteers 6 months post-administration, albeit sample size limitations prevent us from speculating on the effect/s of worm removal on the gut microbiota and metabolome. Future studies with longer monitoring of qualitative and qualitative fluctuations in faecal microbiota post-treatment may assist shedding light on this point. Whilst our findings add valuable knowledge to the emerging area of host-parasite-microbiota interactions, mechanistic studies in experimental models of infection and disease are necessary to shed light on the likely contribution of parasite-associated modifications in gut microbiome and metabolism to the anti-inflammatory properties of parasitic helminths.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Committee for clinical experimentation for the Province of Verona (Comitato Etico per la Sperimentazione Clinica delle Province di Verona e Rovigo, protocol number 34678). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects enrolled in the study.

Study area and characteristics of the population

Individual faecal samples from 20 volunteers (from 4 regions in northern Italy) with confirmed infections by S. stercoralis (S+) as assessed by Real-Time PCR (rtPCR; cf.100), performed at the Centre for Tropical Diseases of the Sacro Cuore Hospital (Negrar, Italy) during routine screening, were examined for microbiota and metabolite profiling as described below. Of these volunteers, 15 were from the Veneto region, three from Lombardia, one from Piemonte, and one from Emilia-Romagna (Supplementary Fig. S1). Subjects were both men (n = 12) and women (n = 8) of an average age of 74 (range 49–86 ± 11.5) (Supplementary Fig. S1) with no overt symptoms of GI disease and no recent history of anthelmintic treatment. Briefly, immediately following collection of individual faecal samples from each of these volunteers, aliquots (~250 mg) were examined for evidence of patent infections by GI helminths (S. stercoralis, Strongyloides fuelleborni, N. americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale, Trichostrongylus spp., Ternidens deminutus, and Oesophagostomum spp.) using the Agar Plate Copro-Culture Method (http://www.tropicalmed.eu), whilst rtPCR analyses were conducted to detect possible co-infections with Schistosoma spp. and Hymenolepis nana100,101. The remainders of each sample were stored at −80 °C for subsequent microbiota and metabolite profiling (see below). Patent infections by S. stercoralis were unequivocally confirmed by DNA extractions from individual faecal samples (see below) followed by rtPCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene100. Upon confirmation of diagnosis, infected volunteers were treated with ivermectin (Stromectol®, Merck Sharp & Dohme BV, The Netherlands). From 13 (out of 20) S+ subjects (9 men and 4 women; average age of 76, range 60–84 ± 8.4, referred to as S+pre-treatment) further individual samples were collected 6 months post-treatment (referred to as S+post-treatment) (Supplementary Fig. S1) and processed as described above. Samples that were negative for patent S. stercoralis infection at this time were progressed to microbiota and metabolite profiling (see below). In addition, individual faecal samples from 11 uninfected volunteers (S−) from the Veneto region (5 men and 6 women; average age of 65, range 53–86 ± 10.7; Supplementary Fig. S1) were included for comparative analyses. These volunteers had no overt symptoms of GI disease or any other concomitant disease and had no recent history of antibiotic treatment.

DNA extractions and bacterial 16S rRNA gene Illumina sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted directly from 200 mg of each faecal sample using the MagnaPure LC.2 instrument (Roche Diagnostic, Monza, Italy), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and the DNA isolation kit I (Roche) and stored at −80 °C until further processing. High-throughput sequencing of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was performed by Eurofins Genomics on an Illumina MiSeq platform according to the standard protocols with minor adjustments. Briefly, the V3-V4 region was PCR-amplified using universal primers102, that contained the adapter overhang nucleotide sequences for forward (TACGGGAGGCAGCAG) and reverse primers (CCAGGGTATCTAATCC). Amplicons were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and set up for the index PCR with Nextera XT index primers (Illumina). The indexed samples were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and quantified using the Fragment Analyzer Standard Sensitivity NGS Fragment Analysis Kit (Advanced Analytical) and equal quantities from each sample were pooled. The resulting pooled library was quantified using the Agilent DNA 7500 Kit (Agilent), and sequenced using the v3 chemistry (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads, Illumina).

Bioinformatics and statistical analyses

Raw paired-end Illumina reads were trimmed for 16S rRNA gene primer sequences using Cutadapt (https://cutadapt.readthedocs.org/en/stable/) and sequence data were processed using the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2-2018.4; https://qiime2.org) software suite103. Successfully joined sequences were quality filtered, dereplicated, chimeras identified, and paired-end reads merged in QIIME2 using DADA2104. Sequences were clustered into OTUs on the basis of similarity to known bacterial sequences available in the Greengenes database (v13.8; http://greengenes.secondgenome.com/; 99% sequence similarity cut-off); sequences that could not be matched to references in the Greengenes database were clustered de novo based on pair-wise sequence identity (99% sequence similarity cut-off). The first selected cluster seed was considered as the representative sequence of each OTU. The OTU table with the assigned taxonomy was exported from QIIME2 alongside a weighted UniFrac distance matrix. Singleton OTUs were removed prior to downstream analyses. Cumulative-sum scaling (CSS) was applied, followed by log2 transformation to account for the non-normal distribution of taxonomic counts data. Statistical analyses were executed using the Calypso software105 (cgenome.net/calypso/); samples were investigated using the taxonomic visualisation tool KRONA106 ordinated in explanatory matrices using supervised CCA including infection/treatment status as explanatory variables. Differences in bacterial alpha diversity (Simpson’s index) between study groups (S+ and S−, as well as S+pre-treatment, corresponding S+post-treatment, and S−) were evaluated based on rarefied data (read depth of 6063) and using analysis of variance (ANOVA); F-Tests were used to statistically assess the equality of assessed means (i.e. effect size). To take into account the paired nature of samples from S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment, differences between these sets were assessed using linear mixed effect regression. Differences in beta diversity (weighted UniFrac distances) were identified using Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) and effect size indicated by an R-value (between −1 and + l, with a value of 0 representing the null hypothesis107). Differences in the abundance of individual microbial taxa between groups were assessed using the LEfSe workflow108, taking into account the paired nature of S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment samples.

Metabolite extraction

Metabolites were extracted from 200 mg aliquots of each faecal sample using a methanol–chloroform–water (2:2:1) procedure. 600 μl of methanol–chloroform mix (2:1 v:v) were added, samples were homogenised using stainless steel beads and sonicated for 15 min at room temperature. 200 μl each of chloroform and water were added, the samples were centrifuged and the separated aqueous and lipid phases were collected. The procedure was repeated twice, and the aqueous and lipid fractions from each extraction were pooled. The aqueous layer was dried in a vacuum concentrator (Concentrator Plus, Eppendorf), while the lipid fraction was left to dry overnight at room temperature.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance analysis of aqueous extracts

The dried aqueous fractions were re-dissolved in 600 μl D2O, containing 0.2 mM sodium-3-(tri-methylsilyl)−2,2,3,3-tetradeuteriopropionate (TSP) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, MA, USA) as an internal standard and phosphate buffer (40 mM NaH2PO4/160 mM Na2HPO4). The samples were analysed using an AVANCE II+NMR spectrometer operating at 500.13 MHz for the 1H frequency and 125.721 MHz for the 13C frequency (Bruker, Germany) using a 5 mm TXI probe. The instrument is equipped with TopSpin 3.2. Spectra were collected using a solvent suppression pulse sequence based on a one-dimensional nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) pulse sequence to saturate the residual 1 H water signal (relaxation delay = 2 s, t1 increment = 3 us, mixing time = 150 ms, solvent pre-saturation applied during the relaxation time and the mixing time). One hundred and twenty-eight transients were collected into 16 K data points over a spectral width of 12 ppm at 27 °C. In addition, representative samples of each data set were also examined by two-dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy (COSY), using a standard pulse sequence (cosygpprqf) and 0.5 s water presaturation during relaxation delay, 8 kHz spectral width, 2048 data points, 32 scans per increment, 512 increments. Peaks were assigned using the COSY spectra in conjunction with reference to previous literature and databases and the Chenomx spectral database contained in Chenomx NMR Suite 7.7 (Chenomx, Alberta, Canada). 1D-NMR spectra were processed using TopSpin. Free induction decays were Fourier transformed following multiplication by a line broadening of 1 Hz, and referenced to TSP at 0.0 ppm. Spectra were phased and baseline corrected manually. The integrals of the different metabolites were obtained using Chenomx. Metabolites were normalised to total area and differential abundance of metabolites between S+ and S− subjects, as well as S+post-treatment and S− subjects identified using ANOVA. F-Tests were used to statistically assess the equality of assessed means, while differences between S+pre-treatment and S+post-treatment were determined through paired t-test to account for the paired nature of these samples. Associations among metabolites in the faecal metabolome of each sample group were identified by prediction of correlation networks in Calypso105 (cgenome.net/calypso/). In particular, networks were constructed to identify clusters of co-occurring metabolites based on their association with infection status (i.e., samples from S+ and S−, as well as S+pre-treatment, S+post-treatment and S− subjects). Metabolites and explanatory variables were represented as nodes, relative abundance as node size, and edges represented positive associations, while nodes were coloured according to infection status. Metabolite abundances were associated with infection status using Pearson’s correlation. Nodes were then coloured based on the strength of the association (i.e. Spearman’s rho correlation) with infection status. Networks were generated by computing associations between taxa using Spearman’s rho and the resulting pairwise correlations were converted into dissimilarities and then used to ordinate nodes in a two-dimensional plot by PCoA. Therefore, correlating nodes were located in close proximity and anti-correlating nodes were placed at distant locations in the network.

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry analysis of organic extracts

100 μl of D-25 tridecanoic acid (200 μM in chloroform), 650 μl of chloroform/methanol (1:1 v/v) and 125 μl BF3/methanol (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to 100 μl organic extract dissolved in chloroform/methanol (1:1 v/v) (half of the organic material extracted for each sample). The samples were then incubated at 80 °C for 90 min. 500 μl H2O and 1 ml hexane were added and each vial mixed and the two phases separated. The organic layer was evaporated to dryness before reconstitution in 200 μl hexane for analysis. Using a Trace GC Ultra coupled to a Trace DSQ II mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Hemel Hempstead, UK), 2 μl of the derivatised organic metabolites were injected onto a TR-fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) stationary phase column (Thermo Electron; 30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm; 70% cyanopropyl polysilphenylene-siloxane) with a split ratio of 20. The injector temperature was 230 °C and the helium carrier gas flow rate was 1.2 ml/min. The column temperature was 60 °C for 2 min, increased by 15 °C/min to 150 °C, and then increased at a rate of 4 °C/min to 230 °C (transfer line = 240 °C; ion source = 250 °C, EI = 70 eV). The detector was turned on after 240 s, and full-scan spectra were collected using 3 scans/s over a range of 50–650 m/z. Peaks were assigned using Food Industry FAME Mix (Restek 6098). GC–MS chromatograms were analysed using Xcalibur, version 2.0 (Thermo Fisher), integrating each peak individually, and normalised to total area. The set of metabolic profiles obtained were analysed by univariate analysis. Differential abundance of metabolites between analysis groups was identified using ANOVA, and F-Tests were used to statistically assess the equality of assessed means. Associations among metabolites identified in the faecal metabolome of each sample group were identified by prediction of correlation networks in Calypso105 (cgenome.net/calypso/).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

T.P.J. is the grateful recipient of a PhD scholarship by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) of the United Kingdom. Research in the C.C. laboratory is funded by grants by the Isaac Newton Trust, the Isaac Newton Trust/Wellcome Trust/ University of Cambridge joint grant scheme and by the Royal Society (UK). The authors wish to thank Giulia Lamarca and Barbara Pajola (CTD, Negrar) for technical assistance.

Author Contributions

T.P.J., F.F., D.B., Z.B. and C.C. designed the research; T.P.J., F.F., C.P., F.P. and Ce.C. carried out the research and performed data processing and analyses. T.P.J. and C.C. drafted the manuscript text with input from all other authors. The figures were prepared by T.P.J., with input from all other authors. All authors reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

6/7/2019

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-33937-3.

References

- 1.Rajilic-Stojanovic M, de Vos WM. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:996–1047. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogitsh, B. J., Carter, C. E. & Oeltmann, T. N. Human parasitology (Academic Press, 2013).

- 3.Parfrey LW, Walters WA, Knight R. Microbial eukaryotes in the human microbiome: ecology, evolution, and future directions. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:153. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann C, et al. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theriot CM, Young VB. Interactions between the gastrointestinal microbiome and Clostridium difficile. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:445–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:676–684. doi: 10.1038/ni.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown EM, Sadarangani M, Finlay BB. The role of the immune system in governing host-microbe interactions in the intestine. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:660–667. doi: 10.1038/ni.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Backhed F. Host-Bacterial Mutualism in the Human Intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berer K, et al. Gut microbiota from multiple sclerosis patients enables spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:10719–10724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711233114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea-Donohue T, et al. The role of IL-4 in Heligmosomoides polygyrus-induced alterations in murine intestinal epithelial cell function. J Immunol. 2001;167:2234–2239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enobe CS, et al. Early stages of Ascaris suum induce airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in a mouse model. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girod N, Brown A, Pritchard DI, Billett EE. Successful vaccination of BALB/c mice against human hookworm (Necator americanus): the immunological phenotype of the protective response. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:71–80. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van Ree R. Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis. Science. 2002;296:490–494. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5567.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadhurst MJ, et al. IL-22+CD4+T cells are associated with therapeutic Trichuris trichiura infection in an ulcerative colitis patient. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:60ra88. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summers Robert W., Elliott David E., Urban Joseph F., Thompson Robin A., Weinstock Joel V. Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4):825–832. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summers RW, et al. Trichuris suis seems to be safe and possibly effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2034–2041. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF, Jr., Thompson R, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:87–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croese J, et al. A proof of concept study establishing Necator americanus in Crohn’s patients and reservoir donors. Gut. 2006;55:136–137. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandborn W. J., Elliott D. E., Weinstock J., Summers R. W., Landry-Wheeler A., Silver N., Harnett M. D., Hanauer S. B. Randomised clinical trial: the safety and tolerability ofTrichuris suisova in patients with Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;38(3):255–263. doi: 10.1111/apt.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daveson A. James, Jones Dianne M., Gaze Soraya, McSorley Henry, Clouston Andrew, Pascoe Andrew, Cooke Sharon, Speare Richard, Macdonald Graeme A., Anderson Robert, McCarthy James S., Loukas Alex, Croese John. Effect of Hookworm Infection on Wheat Challenge in Celiac Disease – A Randomised Double-Blinded Placebo Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croese J, Gaze ST, Loukas A. Changed gluten immunity in celiac disease by Necator americanus provides new insights into autoimmunity. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correale J, Farez M. Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:97–108. doi: 10.1002/ana.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming JO, et al. Probiotic helminth administration in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase 1 study. Mult Scler. 2011;17:743–754. doi: 10.1177/1352458511398054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benzel F, et al. Immune monitoring of Trichuris suis egg therapy in multiple sclerosis patients. J Helminthol. 2012;86:339–347. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X11000460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosche B, Wernecke KD, Ohlraun S, Dorr JM, Paul F. Trichuris suis ova in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome (TRIOMS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:112. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards LJ, Constantinescu CS. Parasite immunomodulation in autoimmune disease: focus on multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009;5:487–489. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harnett W, Harnett MM. Helminth-derived immunomodulators: can understanding the worm produce the pill? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:278. doi: 10.1038/nri2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepherd C, et al. Identifying the immunomodulatory components of helminths. Parasite Immunol. 2015;37:293–303. doi: 10.1111/pim.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaccone P, Cooke A. Vaccine against autoimmune disease: can helminths or their products provide a therapy? Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harnett William. Secretory products of helminth parasites as immunomodulators. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2014;195(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coakley G, et al. Extracellular vesicles from a helminth parasite suppress macrophage activation and constitute an effective vaccine for protective immunity. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1545–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blaser, K. T cell regulation in allergy, asthma and atopic skin diseases. 112–123 (Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers, 2008).

- 39.McSorley HJ, Hewitson JP, Maizels RM. Immunomodulation by helminth parasites: defining mechanisms and mediators. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McSorley HJ, Maizels RM. Helminth infections and host immune regulation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:585–608. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05040-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segura M, Su Z, Piccirillo C, Stevenson MM. Impairment of dendritic cell function by excretory-secretory products: a potential mechanism for nematode-induced immunosuppression. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1887–1904. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smits HH, Yazdanbakhsh M. Chronic helminth infections modulate allergen-specific immune responses: protection against development of allergic disorders? Ann Med. 2007;39:428–439. doi: 10.1080/07853890701436765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varyani F, Fleming JO, Maizels RM. Helminths in the gastrointestinal tract as modulators of immunity and pathology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2017;312:G537–G549. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brosschot Tara P., Reynolds Lisa A. The impact of a helminth-modified microbiome on host immunity. Mucosal Immunology. 2018;11(4):1039–1046. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cantacessi C, et al. Impact of experimental hookworm infection on the human gut microbiota. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1431–1434. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Croese J, et al. Experimental hookworm infection and gluten microchallenge promote tolerance in celiac disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giacomin P, et al. Experimental hookworm infection and escalating gluten challenges are associated with increased microbial richness in celiac subjects. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13797. doi: 10.1038/srep13797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giacomin P, et al. Changes in duodenal tissue-associated microbiota following hookworm infection and consecutive gluten challenges in humans with coeliac disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36797. doi: 10.1038/srep36797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaiss MM, et al. The intestinal microbiota contributes to the ability of helminths to modulate allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:998–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee SC, et al. Helminth colonization is associated with increased diversity of the gut microbiota. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenkins TP, et al. Infections by human gastrointestinal helminths are associated with changes in faecal microbiota diversity and composition. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosa BA, et al. Differential human gut microbiome assemblages during soil-transmitted helminth infections in Indonesia and Liberia. Microbiome. 2018;6:33. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooper Philip, Walker Alan W., Reyes Jorge, Chico Martha, Salter Susannah J., Vaca Maritza, Parkhill Julian. Patent Human Infections with the Whipworm, Trichuris trichiura, Are Not Associated with Alterations in the Faecal Microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e76573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cortés A, Toledo R, Cantacessi C. Classic models for new perspectives: delving into helminth–microbiota–immune system interactions. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:640–654. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reynolds LA, et al. Commensal-pathogen interactions in the intestinal tract: lactobacilli promote infection with, and are promoted by, helminth parasites. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:522–532. doi: 10.4161/gmic.32155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes KS, et al. Exploitation of the intestinal microflora by the parasitic nematode Trichuris muris. Science. 2010;328:1391–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1187703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynolds LA, Finlay BB, Maizels RM. Cohabitation in the intestine: interactions among helminth parasites, bacterial microbiota, and host immunity. J Immunol. 2015;195:4059–4066. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nutman TB. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology. 2016;144:263–273. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schär F, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puthiyakunnon S, et al. Strongyloidiasis - an insight into its global prevalence and management. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bisoffi Z, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: A plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Viney M. Strongyloides. Parasitology. 2017;144:259–262. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016001773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buonfrate D, et al. Epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in northern Italy: Results of a multicentre case–control study, February 2013 to July 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21:30310. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.31.30310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hopkins MJ, Macfarlane GT. Changes in predominant bacterial populations in human faeces with age and with Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:448–454. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-5-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajilic-Stojanovic M, et al. Development and application of the human intestinal tract chip, a phylogenetic microarray: Analysis of universally conserved phylotypes in the abundant microbiota of young and elderly adults. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1736–1751. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodmansey EJ, McMurdo ME, Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Comparison of compositions and metabolic activities of fecal microbiotas in young adults and in antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated elderly subjects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6113–6122. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6113-6122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mueller S, et al. Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1027–1033. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1027-1033.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Santoru ML, et al. Cross sectional evaluation of the gut-microbiome metabolome axis in an Italian cohort of IBD patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9523. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10034-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mosca A, Leclerc M, Hugot JP. Gut microbiota diversity and human diseases: Should we reintroduce key predators in our ecosystem? Front Microbiol. 2016;7:455. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Menni C, et al. Gut microbiome diversity and high-fibre intake are related to lower long-term weight gain. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017;41:1099. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giacomin Paul, Croese John, Krause Lutz, Loukas Alex, Cantacessi Cinzia. Suppression of inflammation by helminths: a role for the gut microbiota? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;370(1675):20140296. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. Commensal Clostridia: Leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 2013;5:23–23. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kekkonen Riina A, Kajasto Elina, Miettinen Minja, Veckman Ville, Korpela Riitta, Julkunen Ilkka. Probiotic Leuconostoc mesenteroides ssp. cremoris and Streptococcus thermophilus induce IL-12 and IFN-γ production. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(8):1192. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kreisinger, J., Bastien, G., Hauffe, H. C., Marchesi, J. & Perkins, S. E. Interactions between multiple helminths and the gut microbiota in wild rodents. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci370 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Walk ST, Blum AM, Ewing SA, Weinstock JV, Young VB. Alteration of the murine gut microbiota during infection with the parasitic helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1841–1849. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fricke WF, et al. Type 2 immunity-dependent reduction of segmented filamentous bacteria in mice infected with the helminthic parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Microbiome. 2015;3:40. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rausch S, et al. Small intestinal nematode infection of mice is associated with increased enterobacterial loads alongside the intestinal tract. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holm JB, et al. Chronic Trichuris muris infection decreases diversity of the intestinal microbiota and concomitantly increases the abundance of lactobacilli. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su C, et al. Helminth-induced alterations of the gut microbiota exacerbate bacterial colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;11:144–157. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Duarte AM, et al. Helminth infections and gut microbiota - a feline perspective. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:625. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1908-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Plieskatt JL, et al. Infection with the carcinogenic liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini modifies intestinal and biliary microbiome. FASEB J. 2013;27:4572–4584. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-232751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jenkins TP, et al. Schistosoma mansoni infection is associated with quantitative and qualitative modifications of the mammalian intestinal microbiota. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12072. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30412-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dziarski R, Park SY, Kashyap DR, Dowd SE, Gupta D. Pglyrp-regulated gut microflora Prevotella falsenii, Parabacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides eggerthii enhance and Alistipes finegoldii attenuates colitis in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Buford TW. (Dis)Trust your gut: The gut microbiome in age-related inflammation, health, and disease. Microbiome. 2017;5:80. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0296-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Biagi E, et al. Through ageing, and beyond: Gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reeves AE, Koenigsknecht MJ, Bergin IL, Young VB. Suppression of Clostridium difficile in the gastrointestinal tracts of germfree mice inoculated with a murine isolate from the family Lachnospiraceae. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3786–3794. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00647-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martin I, et al. Dynamic changes in human-gut microbiome in relation to a placebo-controlled anthelminthic trial in Indonesia. PLoS Negl Tropl Dis. 2018;12:e0006620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tidjani Alou M, Lagier JC, Raoult D. Diet influence on the gut microbiota and dysbiosis related to nutritional disorders. Human Microbiome Journal. 2016;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.humic.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lippert K, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with glucose metabolism disorders and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. Benef Microbes. 2017;8:545–556. doi: 10.3920/BM2016.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Houlden A, et al. Chronic Trichuris muris infection in C57BL/6 mice causes significant changes in host microbiota and metabolome: Effects reversed by pathogen clearance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morowitz MJ, Carlisle E, Alverdy JC. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg Clin North Am. 2011;91:771–785. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Macfarlane GT, Allison C, Gibson SAW, Cummings JH. Contribution of the microflora to proteolysis in the human large intestine. J Appl Bacteriol. 1988;64:37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1988.tb02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH, Macfarlane S, Gibson GR. Influence of retention time on degradation of pancreatic enzymes by human colonic bacteria grown in a 3‐stage continuous culture system. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;67:521–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davila AM, et al. Re-print of “Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: Role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host”. Pharmacological Res. 2013;69:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dai ZL, Wu G, Zhu WY. Amino acid metabolism in intestinal bacteria: Links between gut ecology and host health. Front Biosci. 2011;16:1768–1786. doi: 10.2741/3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Allison C, Macfarlane GT. Influence of pH, nutrient availability, and growth rate on amine production by Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium perfringens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2894–2898. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2894-2898.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tomé D, Bos CC. Lysine requirement through the human life cycle. J Nutr. 2007;137:1642S–1645S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1642S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duan Y, et al. The role of leucine and its metabolites in protein and energy metabolism. Amino Acids. 2016;48:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Motil KJ, et al. Whole-body leucine and lysine metabolism: Response to dietary protein intake in young men. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:E712–E721. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.240.6.E712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Verweij JJ, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Obeng BB, et al. Application of a circulating-cathodic-antigen (CCA) strip test and real-time PCR, in comparison with microscopy, for the detection of Schistosoma haematobium in urine samples from Ghana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:625–633. doi: 10.1179/136485908X337490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Klindworth A, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Caporaso J Gregory, Kuczynski Justin, Stombaugh Jesse, Bittinger Kyle, Bushman Frederic D, Costello Elizabeth K, Fierer Noah, Peña Antonio Gonzalez, Goodrich Julia K, Gordon Jeffrey I, Huttley Gavin A, Kelley Scott T, Knights Dan, Koenig Jeremy E, Ley Ruth E, Lozupone Catherine A, McDonald Daniel, Muegge Brian D, Pirrung Meg, Reeder Jens, Sevinsky Joel R, Turnbaugh Peter J, Walters William A, Widmann Jeremy, Yatsunenko Tanya, Zaneveld Jesse, Knight Rob. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Callahan BJ, et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zakrzewski M, et al. Calypso: a user-friendly web-server for mining and visualizing microbiome-environment interactions. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:782–783. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clarke KR. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral Ecology. 1993;18:117–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1993.tb00438.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Segata Nicola, Izard Jacques, Waldron Levi, Gevers Dirk, Miropolsky Larisa, Garrett Wendy S, Huttenhower Curtis. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biology. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.